Lifetime Practice and Intention to Use Contraception After Induced Abortion Among Serbian Women in Belgrade

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

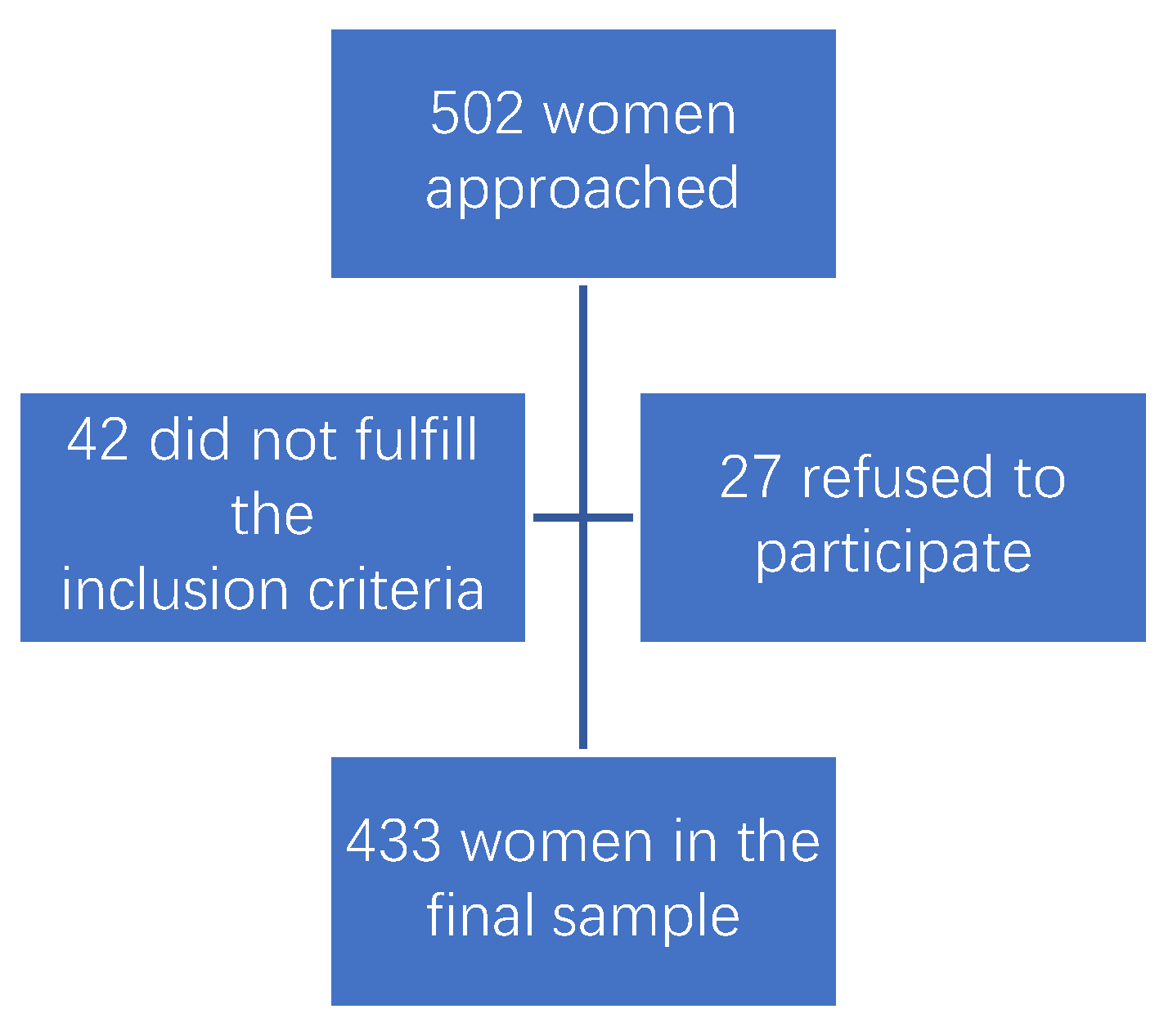

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample

3.2. Knowledge of Contraception

3.3. Lifetime Contraception Use

3.4. Intention to Use Contraception in the Future

3.5. Differences Between Women

3.6. Correlation Results

3.7. Regression Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- eClinicalMedicine. Access to safe abortion is a fundamental human right. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Abortion. Key Facts. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/abortion (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Induced abortion. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazibara, T.; Trajkovic, G.; Kovacevic, N.; Kurtagic, I.; Nurkovic, S.; Kisic-Tepavcevic, D.; Pekmezovic, T. Oral contraceptives usage patterns: Study of knowledge, attitudes and experience in Belgrade female medical students. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 288, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milic, M.; Gazibara, T.; Stevanovic, J.; Parlic, M.; Nicholson, D.; Mitic, K.; Lazic, D.; Dotlic, J. Patterns of condom use in a university student population residing in a high-risk area for HIV infection. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2020, 25, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlecky, K.; Stankovic, Z. Contraception for adolescents after abortion. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2016, 21, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milic, M.; Dotlic, J.; Stevanovic, J.; Parlic, M.; Mitic, K.; Nicholson, D.; Arsovic, A.; Gazibara, T. Relevance of students’ demographic characteristics, sources of information and personal attitudes towards HIV testing for HIV knowledge: Evidence from a post-conflict setting. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2021, 53, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasevic, M. Induced abortion, epidemiological problem. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 1995, 123, 77–80. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Rasevic, M.; Sedlecky, K. The abortion issue in Serbia. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2009, 14, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Census 2022. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-us/oblasti/popis/ (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Sedgh, G.; Singh, S.; Shah, I.H.; Ahman, E.; Henshaw, S.K.; Bankole, A. Induced abortion: Incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet 2012, 379, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, M.A.; Gould, H.; Foster, D.G. Understanding why women seek abortions in the US. BMC Womens Health 2013, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Desai, S.; Crowell, M.; Sedgh, G. Reasons why women have induced abortions: A synthesis of findings from 14 countries. Contraception 2017, 96, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radoman, M. Attitudes and experiences of women on abortion. Socioloski Pregled 2015, 49, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.; Costa, A.R.; Neves, J.; Pacheco, A.; Almeida, M.C.; Bombas, T.; Silva, D.P. Perception of oral contraception—Do women think differently from gynaecologists? Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2023, 28, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Guen, M.; Schantz, C.; Régnier-Loilier, A.; de La Rochebrochard, E. Reasons for rejecting hormonal contraception in Western countries: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 284, 114247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Kamp, A.; Takhar, J. Interrogating the pill: Rising distrust and the reshaping of health risk perceptions in the social media age. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 331, 116081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, J. The complex relationship between contraception and abortion. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 62, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer Hultstrand, J.; Törnroos, E.; Tydén, T.; Larsson, M.; Makenzius, M.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Sundström-Poromaa, I.; Ekstrand Ragnar, M. Contraceptive use among women seeking an early induced abortion in Sweden. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolic, Z.; Djikanovic, B. Differences in the use of contraception between Roma and non-Roma women in Serbia. J. Public Health 2015, 37, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, A.; Ertem, M.; Saka, G.; Akdeniz, N. Post abortion family planning counseling as a tool to increase contraception use. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlecky, K.; Rasevic, M. Are Serbian gynaecologists in line with modern family planning? Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2008, 13, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosavljevic, J.; Krajnovic, D.; Bogavac-Stanojevic, N.; Mitrovic-Jovanovic, A. Serbian gynaecologists’ views on contraception and abortion. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2015, 20, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, H.; Holton, S.; Kirkman, M.; Bayly, C.; Jordan, L.; McNamee, K.; McBain, J.; Sinnott, V.; Fisher, J. Abortion: Findings from women and men participating in the Understanding Fertility Management in contemporary Australia national survey. Sex. Health 2017, 14, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exavery, A.; Kanté, A.M.; Jackson, E.; Noronha, J.; Sikustahili, G.; Tani, K.; Mushi, H.P.; Baynes, C.; Ramsey, K.; Hingora, A.; et al. Role of condom negotiation on condom use among women of reproductive age in three districts in Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Croft, J.B.; Wheaton, A.G.; Kanny, D.; Cunningham, T.J.; Lu, H.; Onufrak, S.; Malarcher, A.M.; Greenlund, K.J.; Giles, W.H. Clustering of Five Health-Related Behaviors for Chronic Disease Prevention Among Adults, United States, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sium, A.F.; Prager, S.; Abubeker, F.A.; Don Eliseo, L.-P., III; Gudu, W. Abortion care in women with underlying medical conditions: The role of multidisciplinary team approach in increasing safety of abortion procedures. Public Health Chall. 2023, 2, e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Lifetime Contraception Use | Between Groups p | Future Plan to Use Contraception | Between Groups p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Some Time | No | Yes | ||||

| Age group | 16 to 25 | 18 | 66 | 0.710 | 22 | 62 | 0.482 |

| 26 to 35 | 37 | 168 | 63 | 142 | |||

| over 35 | 27 | 117 | 45 | 99 | |||

| Nationality | Serbian | 71 | 342 | 0.001 | 119 | 294 | 0.013 |

| Roma | 8 | 4 | 7 | 5 | |||

| other minorities * | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Religion | Orthodox Christian | 73 | 329 | 0.166 | 120 | 282 | 0.865 |

| Catholic Christian | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Muslim | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | |||

| other | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| atheist | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | |||

| Education | no or primary | 15 | 26 | 0.001 | 18 | 23 | 0.004 |

| secondary | 53 | 205 | 81 | 177 | |||

| high | 14 | 120 | 31 | 103 | |||

| Employment | yes | 45 | 210 | 0.621 | 69 | 186 | 0.240 |

| no | 33 | 111 | 54 | 90 | |||

| student | 4 | 30 | 7 | 27 | |||

| Relationship status | single/divorced/widow | 6 | 24 | 0.720 | 11 | 19 | 0.898 |

| coupled | 11 | 58 | 13 | 56 | |||

| living together | 13 | 34 | 22 | 25 | |||

| married | 52 | 235 | 84 | 203 | |||

| Professional activity | vigorous | 15 | 50 | 0.470 | 16 | 49 | 0.736 |

| moderate | 44 | 193 | 76 | 161 | |||

| sedentary | 23 | 108 | 38 | 93 | |||

| Recreation | no | 68 | 281 | 0.555 | 111 | 238 | 0.100 |

| yes | 14 | 70 | 19 | 65 | |||

| Smoking status | smoker | 38 | 156 | 0.893 | 67 | 127 | 0.047 |

| ex-smoker | 9 | 58 | 20 | 47 | |||

| non-smoker | 35 | 137 | 43 | 129 | |||

| Smoking amount | ≤20 cigarettes | 34 | 156 | 0.754 | 67 | 123 | 0.087 |

| >20 cigarettes | 13 | 58 | 20 | 51 | |||

| Alcohol | no | 53 | 188 | 0.070 | 78 | 163 | 0.234 |

| yes | 29 | 163 | 52 | 140 | |||

| Alcohol frequency | weekly | 5 | 26 | 0.914 | 8 | 23 | 0.802 |

| monthly | 5 | 33 | 10 | 28 | |||

| rarely | 19 | 104 | 34 | 89 | |||

| Chronic illnesses | no | 74 | 331 | 0.179 | 125 | 280 | 0.147 |

| yes | 8 | 20 | 5 | 23 | |||

| Gynecological illnesses | no | 64 | 258 | 0.397 | 96 | 226 | 0.872 |

| yes | 18 | 93 | 34 | 77 | |||

| Menstrual cycle | regular | 71 | 304 | 0.238 | 118 | 257 | 0.369 |

| not regular | 11 | 47 | 12 | 46 | |||

| Pregnancies before | no | 16 | 45 | 0.147 | 23 | 38 | 0.734 |

| yes | 66 | 306 | 107 | 265 | |||

| Cesarean section before | no | 73 | 295 | 0.256 | 116 | 252 | 0.106 |

| yes | 9 | 56 | 14 | 51 | |||

| Abortion | first | 42 | 150 | 0.164 | 62 | 130 | 0.359 |

| recurrent | 40 | 201 | 68 | 173 | |||

| Characteristics | Overall Sample (Frequency) | Knowledge About Contraception | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bad (Frequency) | Good (Frequency) | Between Groups p | |||

| Condom | no | 128 | 81 | 47 | 0.001 |

| yes | 305 | 84 | 221 | ||

| Intrauterine device | no | 418 | 160 | 258 | 0.699 |

| yes | 15 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Hormonal contraception | no | 357 | 145 | 212 | 0.020 |

| yes | 76 | 20 | 56 | ||

| Postcoital contraception | no | 304 | 125 | 179 | 0.048 |

| yes | 129 | 40 | 89 | ||

| Interrupted coitus | no | 305 | 138 | 167 | 0.001 |

| yes | 128 | 27 | 101 | ||

| Counting fertile days | no | 319 | 137 | 182 | 0.001 |

| yes | 114 | 28 | 86 | ||

| Other contraception | no | 430 | 163 | 267 | 0.307 |

| yes | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Predictors | Coefficient B | Coefficient Wald | p | OR | Low 95% CI for OR | High 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.959 | 1.001 | 0.963 | 1.041 |

| Nationality | −0.168 | 0.236 | 0.627 | 0.845 | 0.429 | 1.664 |

| Religion | 0.103 | 0.324 | 0.569 | 1.108 | 0.778 | 1.578 |

| Education | 0.182 | 4.648 | 0.031 | 1.199 | 1.017 | 1.415 |

| Employment | 0.167 | 0.826 | 0.364 | 1.181 | 0.825 | 1.693 |

| Salary (EUR) | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.912 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.001 |

| Relationships | −0.055 | 0.206 | 0.650 | 0.947 | 0.747 | 1.200 |

| Professional activity | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.913 | 1.012 | 0.816 | 1.255 |

| Recreation | −0.116 | 0.196 | 0.658 | 0.890 | 0.532 | 1.490 |

| Smoking | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.979 | 1.003 | 0.805 | 1.250 |

| Alcohol | 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.883 | 1.032 | 0.678 | 1.571 |

| Chronic illness | 0.398 | 0.807 | 0.369 | 1.489 | 0.624 | 3.552 |

| Gynecologic illness | −0.012 | 0.002 | 0.960 | 0.988 | 0.617 | 1.583 |

| Parity | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.976 | 1.002 | 0.866 | 1.159 |

| Cesarean section | 0.055 | 0.035 | 0.852 | 1.057 | 0.594 | 1.880 |

| Recurrent abortion | 0.308 | 1.426 | 0.232 | 1.360 | 0.821 | 2.254 |

| Constant | −0.283 | 0.592 | 0.041 | 0.753 |

| Predictors | Coefficient B | Coefficient Wald | p | OR | Low 95% CI for OR | High 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.011 | 0.207 | 0.649 | 0.989 | 0.941 | 1.038 |

| Nationality | −0.899 | 7.879 | 0.005 | 0.407 | 0.217 | 0.762 |

| Religion | 0.077 | 0.108 | 0.742 | 1.080 | 0.683 | 1.710 |

| Education | 0.369 | 12.910 | 0.001 | 1.447 | 1.183 | 1.769 |

| Employment | 0.253 | 1.126 | 0.289 | 1.288 | 0.807 | 2.056 |

| Salary (EUR) | 0.000 | 0.169 | 0.681 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.001 |

| Relationships | −0.072 | 0.229 | 0.632 | 0.931 | 0.693 | 1.250 |

| Professional activity | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.992 | 1.001 | 0.755 | 1.329 |

| Recreation | 0.084 | 0.058 | 0.810 | 1.088 | 0.548 | 2.158 |

| Smoking | −0.048 | 0.115 | 0.734 | 0.953 | 0.720 | 1.260 |

| Alcohol | 0.216 | 0.601 | 0.438 | 1.241 | 0.719 | 2.143 |

| Chronic illness | −0.146 | 2.684 | 0.041 | 0.463 | 0.185 | 1.163 |

| Gynecologic illness | 0.133 | 0.173 | 0.677 | 1.142 | 0.611 | 2.132 |

| Parity | 0.141 | 4.143 | 0.042 | 1.152 | 1.005 | 1.319 |

| Cesarean section | 0.404 | 0.953 | 0.329 | 1.498 | 0.666 | 3.370 |

| Recurrent abortion | −0.016 | 0.002 | 0.963 | 0.984 | 0.505 | 1.918 |

| Constant | 0.551 | 0.809 | 0.036 | 1.735 |

| Predictors | Coefficient B | Coefficient Wald | p | OR | Low 95% CI for OR | High 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.035 | 2.679 | 0.102 | 0.966 | 0.926 | 1.007 |

| Nationality | −0.864 | 5.519 | 0.019 | 0.422 | 0.205 | 0.867 |

| Religion | 0.216 | 1.000 | 0.317 | 1.242 | 0.812 | 1.898 |

| Education | 0.220 | 4.623 | 0.032 | 1.246 | 1.020 | 1.522 |

| Employment | −0.132 | 0.443 | 0.506 | 0.876 | 0.593 | 1.294 |

| Salary (EUR) | 0.000 | 0.472 | 0.492 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.001 |

| Relationships | −0.013 | 0.010 | 0.919 | 0.987 | 0.765 | 1.273 |

| Professional activity | −0.154 | 1.621 | 0.203 | 0.857 | 0.676 | 1.087 |

| Recreation | 0.371 | 1.475 | 0.225 | 1.449 | 0.796 | 2.637 |

| Smoking | 0.244 | 3.935 | 0.047 | 1.276 | 1.003 | 1.623 |

| Alcohol | 0.145 | 0.387 | 0.534 | 1.156 | 0.732 | 1.828 |

| Chronic illness | 1.188 | 4.576 | 0.032 | 3.282 | 1.105 | 9.749 |

| Gynecologic illness | −0.122 | 0.224 | 0.636 | 0.885 | 0.533 | 1.469 |

| Parity | 0.034 | 0.174 | 0.676 | 1.034 | 0.882 | 1.213 |

| Cesarean section | 0.539 | 2.515 | 0.113 | 1.715 | 0.880 | 3.341 |

| Recurrent abortion | 0.217 | 0.598 | 0.439 | 1.242 | 0.717 | 2.151 |

| Constant | 1.465 | 1.898 | 0.048 | 4.329 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gazibara, T.; Bila, J.; Tulic, L.; Maksimovic, N.; Maksimovic, J.; Stojnic, J.; Plavsa, D.; Miloradovic, M.; Radovic, M.; Maksimovic, K.; et al. Lifetime Practice and Intention to Use Contraception After Induced Abortion Among Serbian Women in Belgrade. Medicina 2024, 60, 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60121944

Gazibara T, Bila J, Tulic L, Maksimovic N, Maksimovic J, Stojnic J, Plavsa D, Miloradovic M, Radovic M, Maksimovic K, et al. Lifetime Practice and Intention to Use Contraception After Induced Abortion Among Serbian Women in Belgrade. Medicina. 2024; 60(12):1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60121944

Chicago/Turabian StyleGazibara, Tatjana, Jovan Bila, Lidija Tulic, Natasa Maksimovic, Jadranka Maksimovic, Jelena Stojnic, Dragana Plavsa, Maja Miloradovic, Milos Radovic, Katarina Maksimovic, and et al. 2024. "Lifetime Practice and Intention to Use Contraception After Induced Abortion Among Serbian Women in Belgrade" Medicina 60, no. 12: 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60121944

APA StyleGazibara, T., Bila, J., Tulic, L., Maksimovic, N., Maksimovic, J., Stojnic, J., Plavsa, D., Miloradovic, M., Radovic, M., Maksimovic, K., & Dotlic, J. (2024). Lifetime Practice and Intention to Use Contraception After Induced Abortion Among Serbian Women in Belgrade. Medicina, 60(12), 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60121944