Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax Developed during Anesthetic Induction Aggravated by Positive Pressure Ventilation: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

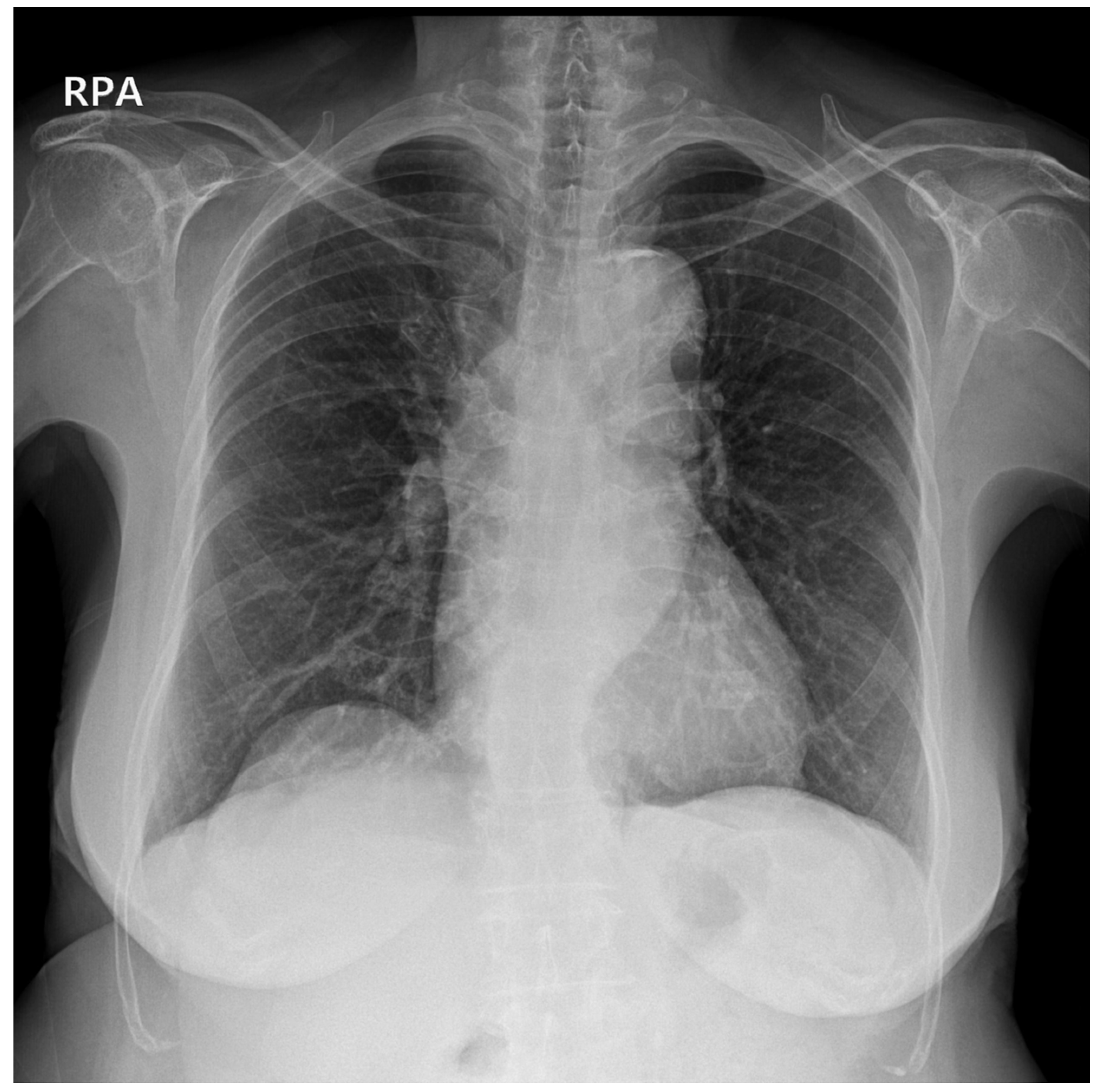

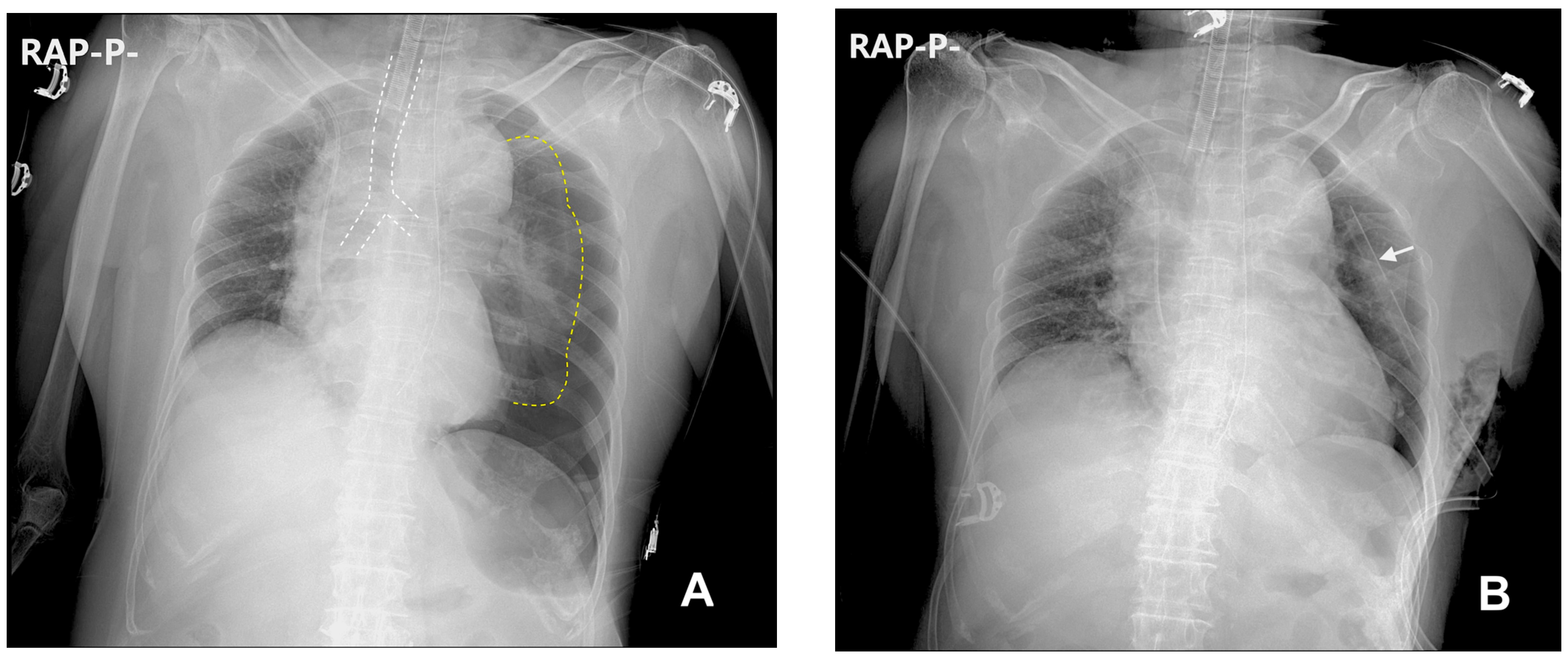

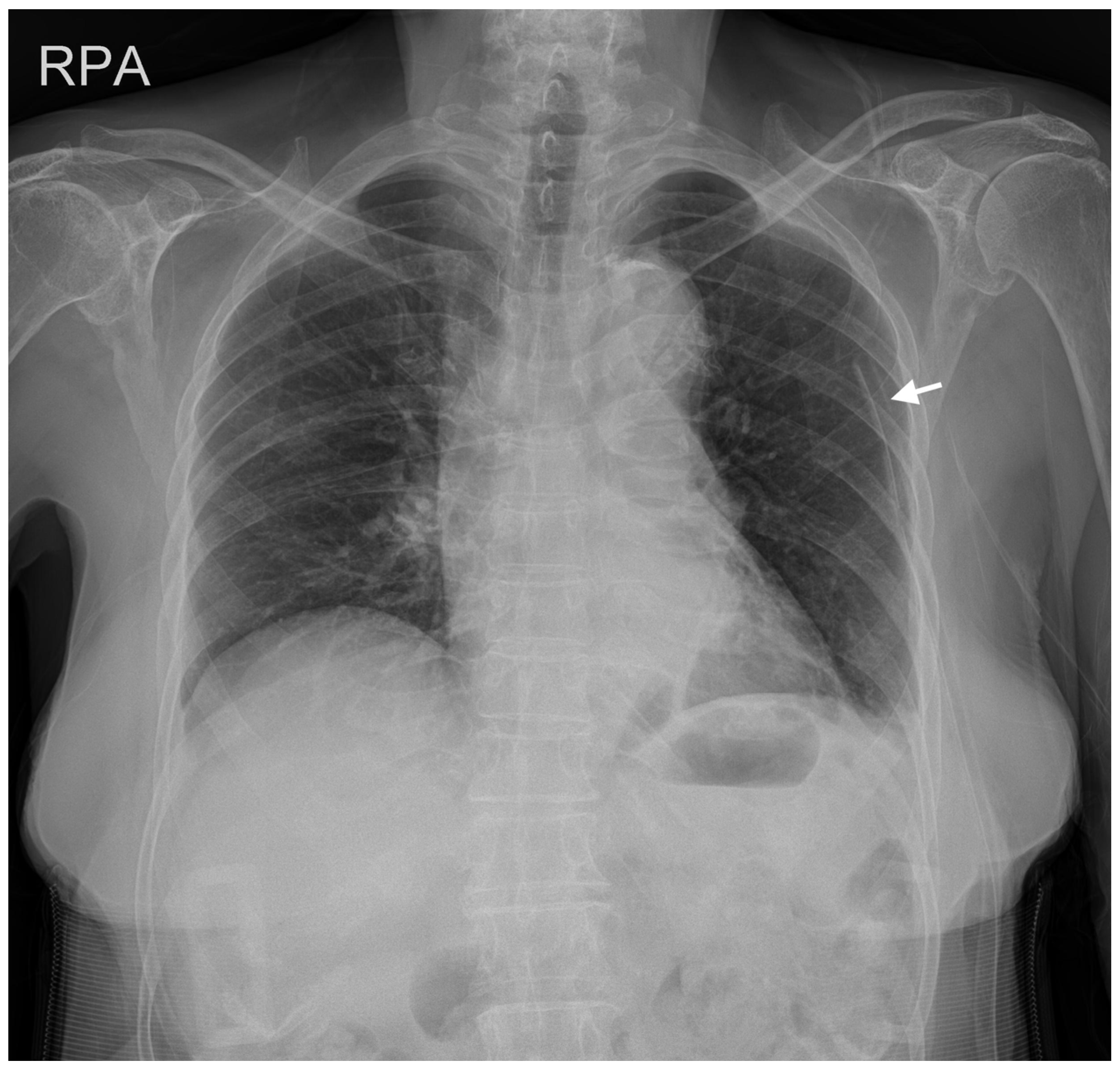

2. Case Description

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bacon, A.K.; Paix, A.D.; Williamson, J.A.; Webb, R.K.; Chapman, M.J. Crisis Management during Anaesthesia: Pneumothorax. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2005, 14, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cheney, F.W.; Posner, K.L.; Caplan, R.A. Adverse Respiratory Events Infrequently Leading to Malpractice Suits A Closed Claims Analysis. Anesthesiology 1991, 75, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, R.; Wasserberger, J.; Balasubramaniam, S. Unsuspected Tension Pneumothorax as a Hidden Cause of Unsuccessful Resuscitation. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1983, 12, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzner, J.; Posner, K.L.; Lam, M.S.; Domino, K.B. Closed Claims’ Analysis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 25, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKnight, C.L.; Burns, B. Pneumothorax. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Sun, S.-F. Iatrogenic Pneumothorax Related to Mechanical Ventilation. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaniti, E.; Provitsaki, C.; Papakonstantinou, P.; Tagarakis, G.; Sapalidis, K.; Dalakakis, I.; Gkinas, D.; Grosomanidis, V. Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax-Hemothorax during Induction of General Anaesthesia. Case Rep. Anesthesiol. 2019, 2019, 5017082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyba, M.; Rashad, A.; Al-Fadhli, A.-A. Detection and Management of Intraoperative Pneumothorax during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Case Rep. Anesthesiol. 2020, 2020, e9273903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, D.; Mathew, P.S.; Kurnutala, L.N.; Soghomonyan, S.; Bergese, S.D. Tension Pneumothorax During Surgery for Thoracic Spine Stabilization in Prone Position. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2014, 2, 2324709614537233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinson, D.R.; Ballard, D.W.; Hance, L.G.; Stevenson, M.D.; Clague, V.A.; Rauchwerger, A.S.; Reed, M.E.; Mark, D.G. Kaiser Permanente CREST Network Investigators Pneumothorax Is a Rare Complication of Thoracic Central Venous Catheterization in Community EDs. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 33, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronen, M.C.; Cronen, P.W.; Arino, P.; Ellis, K. Delayed pneumothorax after subclavian vein catheterization and positive pressure ventilation. Br. J. Anaesth. 1991, 67, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Plewa, M.C.; Ledrick, D.; Sferra, J.J. Delayed Tension Penumothorax Complicating Central Venous Catheterization and Positive Pressure Ventilation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1995, 13, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parienti, J.-J.; Mongardon, N.; Mégarbane, B.; Mira, J.-P.; Kalfon, P.; Gros, A.; Marqué, S.; Thuong, M.; Pottier, V.; Ramakers, M.; et al. Intravascular Complications of Central Venous Catheterization by Insertion Site. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.H.; Shapiro, S.B.; Mone, M.C.; Saffle, J.R.; Morris, S.E.; Barton, R.G. Is Immediate Chest Radiograph Necessary after Central Venous Catheter Placement in a Surgical Intensive Care Unit? Am. J. Surg. 2000, 180, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankine, J.; Thomas, A.; Fluechter, D. Diagnosis of Pneumothorax in Critically Ill Adults. Postgrad. Med. J. 2000, 76, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.J.; Leigh-Smith, S.; Faris, P.D.; Blackmore, C.; Ball, C.G.; Robertson, H.L.; Dixon, E.; James, M.T.; Kirkpatrick, A.W.; Kortbeek, J.B.; et al. Clinical Presentation of Patients With Tension Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review. Ann. Surg. 2015, 261, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.K.; Cho, S.I.; Won, Y.J.; Yun, J.H. Bilateral Tension Pneumothorax during Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection under General Anesthesia Diagnosed by Point-of-Care Ultrasound—A Case Report. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021, 16, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chui, J.; Saeed, R.; Jakobowski, L.; Wang, W.; Eldeyasty, B.; Zhu, F.; Fochesato, L.; Lavi, R.; Bainbridge, D. Is Routine Chest X-Ray after Ultrasound-Guided Central Venous Catheter Insertion Choosing Wisely? Chest 2018, 154, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molgaard, O.; Nielsen, M.S.; Handberg, B.B.; Jensen, J.M.; Kjaergaard, J.; Juul, N. Routine X-Ray Control of Upper Central Venous Lines: Is It Necessary? Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2004, 48, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ki, S.; Choi, B.; Cho, S.B.; Hwang, S.; Lee, J. Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax Developed during Anesthetic Induction Aggravated by Positive Pressure Ventilation: A Case Report. Medicina 2023, 59, 1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091631

Ki S, Choi B, Cho SB, Hwang S, Lee J. Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax Developed during Anesthetic Induction Aggravated by Positive Pressure Ventilation: A Case Report. Medicina. 2023; 59(9):1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091631

Chicago/Turabian StyleKi, Seunghee, Beomseok Choi, Seung Bae Cho, Seokwoo Hwang, and Jeonghan Lee. 2023. "Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax Developed during Anesthetic Induction Aggravated by Positive Pressure Ventilation: A Case Report" Medicina 59, no. 9: 1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091631

APA StyleKi, S., Choi, B., Cho, S. B., Hwang, S., & Lee, J. (2023). Unexpected Tension Pneumothorax Developed during Anesthetic Induction Aggravated by Positive Pressure Ventilation: A Case Report. Medicina, 59(9), 1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091631