Multifocal Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis: Case Report and Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

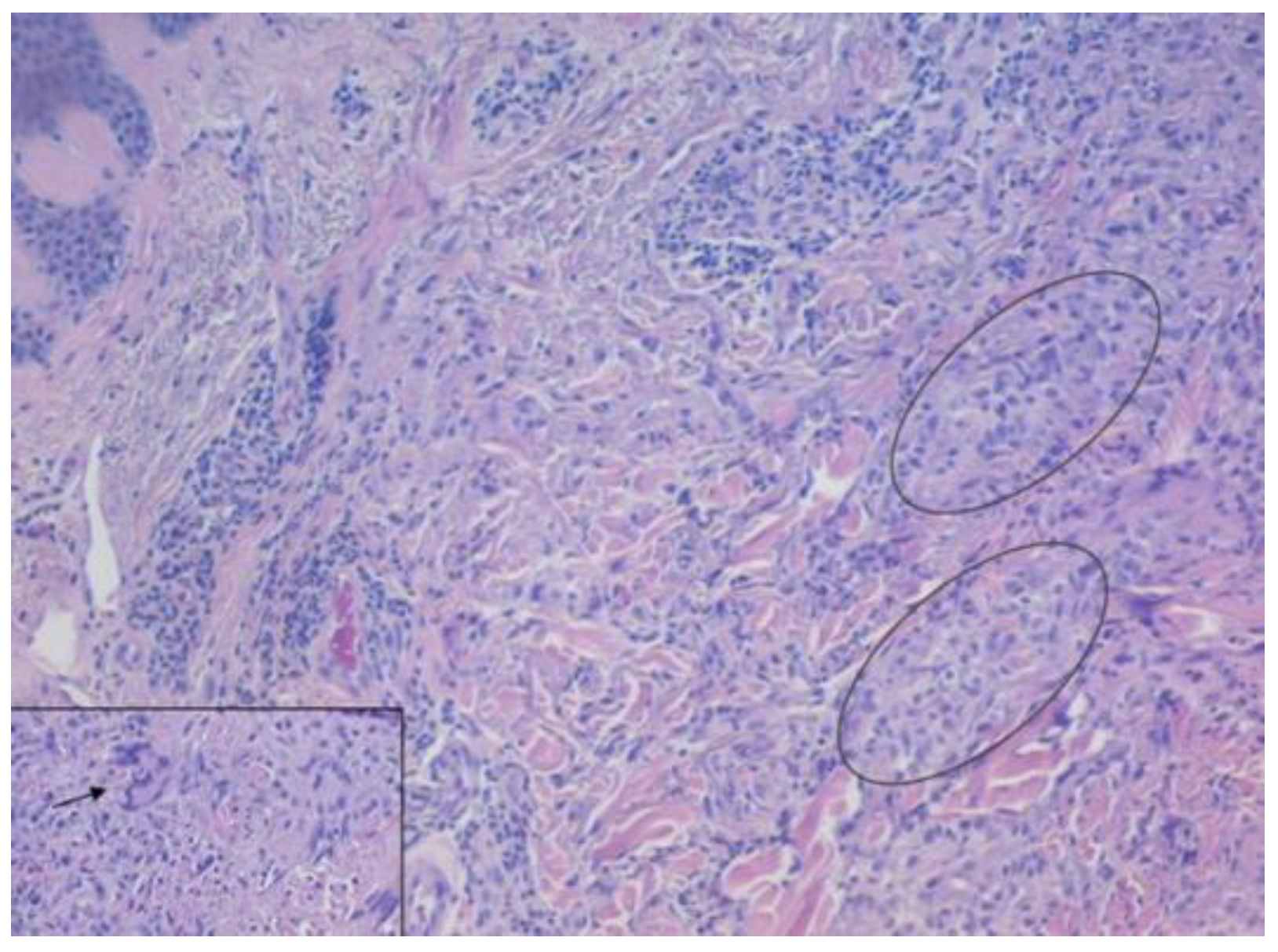

2. Detailed Case Description

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, B.; Kaur, S. Pattern of Cutaneous Tuberculosis in North India. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 1986, 52, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.B.D.; Figueiredo, A.R.; Ferraz, C.E.; de Oliveira, M.H.; da Silva, P.G.; de Medeiros, V.L.S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: Epidemiologic, etiopathogenic and clinical aspects—Part I. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014, 89, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charifa, A.; Mangat, R.; Oakley, A.M. Cutaneous Tuberculosis; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal, V.N.; Sehgal, R.; Bajaj, P.; Sriviastava, G.; Bhattacharya, S. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (TBVC). J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2000, 14, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damevska, K.; Gocev, G. Multifocal tuberculosis verrucosa cutis of 60 years duration. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, e1266–e1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Ansari, N.P. Extensive multifocal tuberculosis verrucosa cutis in a young child. Med. Pract. Rev. 2011, 2, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, J.; Mathai, A.T.; Prasad, P.V.S.; Kaviarasan, P.K. Multifocal tuberculosis verrucosa cutis. Indian J. Dermatol. 2011, 56, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, B.; Acharya, A.; Gautam, S.; Ghimire, S.P.; Mishra, G.; Parajuli, N.; Sapkota, B. Advances in diagnosis of Tuberculosis: An update into molecular diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 4065–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.H.; Tan, B.H.; Goh, C.L.; Tan, K.C.; Tan, M.F.; Ng, W.C.; Tan, W.C. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA using polymerase chain reaction in cutaneous tuberculosis and tuberculids. Int. J. Dermatol. 1999, 38, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, P.-F.; Tzen, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-C.; Su, H.-Y. Polymerase chain reaction based detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in tissues showing granulomatous inflammation without demonstrable acid-fast bacilli. Int. J. Dermatol. 2003, 42, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pebriany, D.; Anwar, A.I.; Djamaludin, W.; Adriani, A.; Amin, S. Successful diagnosis and management of tuberculosis verrucosa cutis using antituberculosis therapy trial approach. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 37, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudarshan, R.; Nayak, K.; Kumar, P.; Kadilkar, U. Rare Case of Multifocal Cutaneous Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis: Posing Clinical and Histopathological Diagnostic Dilemma. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2016, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, V.N.; Verma, P.; Bhattacharya, S.N.; Sharma, S.; Singh, N. Multifocal Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis: A Manifestation Extraordinary of Reactivation Secondary Tuberculosis. Skinmed 2017, 15, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rani, S.; Bansal, P.; Ahuja, A.; Agrawal, D. Varied Presentation of Cutaneous Tuberculosis in a Patient. Indian J. Derm. Diagn Dermatol. 2020, 7, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.V.S.; Ambujam, S.; Paul, E.K.; Krishnasamy, B.; Veliath, A.J. Multifocal Tuberculous Verrucosa Cutis: An Unusual Clinical Presentation. Indian J. Tuberc. 2002, 49, 229–230. [Google Scholar]

- Padmaprasad, M.K. Case report: Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2013, 2, 8274. [Google Scholar]

- Vora, R.V.; Diwan, N.G.; Rathod, K.J. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis with multifocal involvement. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2016, 7, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zyl, L.; du Plessis, J.; Viljoen, J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, J.B.; Figueiredo, A.R.; Ferraz, C.E.; de Oliveira, M.H.; da Silva, P.G.; de Medeiros, V.L.S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: Diagnosis, histopathology and treatment—Part II. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014, 89, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutaneous Tuberculosis: A Clinico-Morphological Study—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27688538/ (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Frankel, A.; Penrose, C.; Emer, J. Cutaneous tuberculosis: A practical case report and review for the dermatologist. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2009, 2, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| First Author/Year | Age/Sex | Country | Duration | Immunosuppression/Cause | Site | Culture TB/Mantoux | Histology | Response to Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damevska K/2013 [4] | 65, F | Republic of North Macedonia | 60 y | Immunocompetent/Ν.A. | Bilateral upper limbs and right lower limb | Negative/(+) | Granulomatous inflamma-tion in the dermis, with small foci of caseation necrosis | Damevska K/2013 [4] |

| Rahman MH/2020 [5] | 12, M | Bangladesh | 2 y | Immunocompetent/bare-footed child | Bilateral extremities | N.A./(+) 17 mm | Hypertrophy of the epidermis and mid-dermalgranuloma with Langhans giant cells | At 6 months, complete resolution of the lesions |

| Rajan J/2011 [6] | 17, M | India | 2 y | Immunocompetent/cattleherd | Left foot | N.A./(+) 17 mm | Hypertrophy of the epidermis and mid-dermal granulomata with Langhans giant cells | At 6 months, all the lesions were completely resolved |

| Vora RV/2016 [7] | 60, F | India | 12 y | Immunocompetent/a thorn prick over her right big toe | Right lower limb | N.A./(−) | Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis of the epidermis. Below the epidermis, multiple granulomas, comprised epithelioid cells with Langhans | At 3 months, improvement of the lesions |

| Sudarshan R/2016 [8] | 69, F | India | 14 y | Immunocompetent/farmer handling cattle occasionally | Right upperlimb, lower limbs, face and nape | Negative/(−) | Hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis. Dermis epithelioid cell granulomas with many Langhans giant cells and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate | Incomplete response after 1 year of therapy |

| Chahar M/2015 [9] | 48, M | India | 15 y | Immunocompetent/walking barefoot | Bilateral buttocks and feet | Negative/(+) | Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis. Upper dermis mononuclear infiltrate and mid-dermis. Epithelioid cell granulomas comprising Langhans giant cells | At 6 months, complete resolution of the lesions |

| Verma R/2014 [10] | 30, M | India | 3 y | Immunocompetent/farmer | Right lower limb | Negative/(+) | Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with irregular acanthosis. Dermis epithelioid cell granulomas with Langhans giant cells and neutrophilic microabscesses | At 6 months, resolution of the lesions |

| Rasineni N/2014 [11] | 42, F | India | 4 m | N.A./N.A. | Left sole and left index finger | Negative/(+) 20 mm | Hyperkeratosis along with numerous lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and Langhans giant cells in the dermis | At 5 months, complete clearance |

| Manjumeena D/2018 [12] | 52, F | India | 20 y | Immunocompetent/trauma while cutting wood | Left leg and foot | Negative/(+) | Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, granulomas composed of lymphocytes, neutrophils, giant cells with central caseous necrosis | At 6 months, regression of the lesions |

| Sehgal VN/2017 [13] | 78, M | India | 1 y | N.A/N.A | upper and lower extremities | N.A./(−) | Epithelial hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and perivascular inflammation in dermis. Epithelioid cell granuloma | At 6 months, complete regression of the lesions |

| Rani S/2020 [14] | 29, M | India | 2 y | Immunocompetent/farmer | Heel, antero-posterior and medial side of leg | Negative/(+) 20 mm | Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, dermal infiltration with epithelioid cell granulomas with Langhans giant cells and occasional central necrosis | At 5 months, improvement of the lesions |

| Prasad PVS/2002 [15] | 35, M | India | 2 y | Immunocompetent | Left hand and left foot | Negative/(−) | Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and mid-dermal tuberculoid granulomas | - |

| Padmaprasad MK/2013 [16] | 49, F | India | 2 y | Immunocompetent/butcher | Right shoulder, right breast, lower limbs and buttocks | Negative/(+) 22 mm | Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dense infiltration of plasma cells and giant cells, and caseation necrosis | N.A. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ntavari, N.; Syrmou, V.; Tourlakopoulos, K.; Malli, F.; Gerogianni, I.; Roussaki, A.-V.; Zafiriou, E.; Ioannou, M.; Tziastoudi, E.; Gourgoulianis, K.I.; et al. Multifocal Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Medicina 2023, 59, 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101758

Ntavari N, Syrmou V, Tourlakopoulos K, Malli F, Gerogianni I, Roussaki A-V, Zafiriou E, Ioannou M, Tziastoudi E, Gourgoulianis KI, et al. Multifocal Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Medicina. 2023; 59(10):1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101758

Chicago/Turabian StyleNtavari, Niki, Vasiliki Syrmou, Konstantinos Tourlakopoulos, Foteini Malli, Irini Gerogianni, Angeliki-Viktoria Roussaki, Efterpi Zafiriou, Maria Ioannou, Eirini Tziastoudi, Konstantinos I. Gourgoulianis, and et al. 2023. "Multifocal Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis: Case Report and Review of the Literature" Medicina 59, no. 10: 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101758

APA StyleNtavari, N., Syrmou, V., Tourlakopoulos, K., Malli, F., Gerogianni, I., Roussaki, A.-V., Zafiriou, E., Ioannou, M., Tziastoudi, E., Gourgoulianis, K. I., & Pantazopoulos, I. (2023). Multifocal Tuberculosis Verrucosa Cutis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Medicina, 59(10), 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101758