The Safety and Efficacy of Nusinersen in the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. A Novel Intervention to Increase Full-Length, Functional SMN Proteins

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

2.6. Outcome of Interest

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

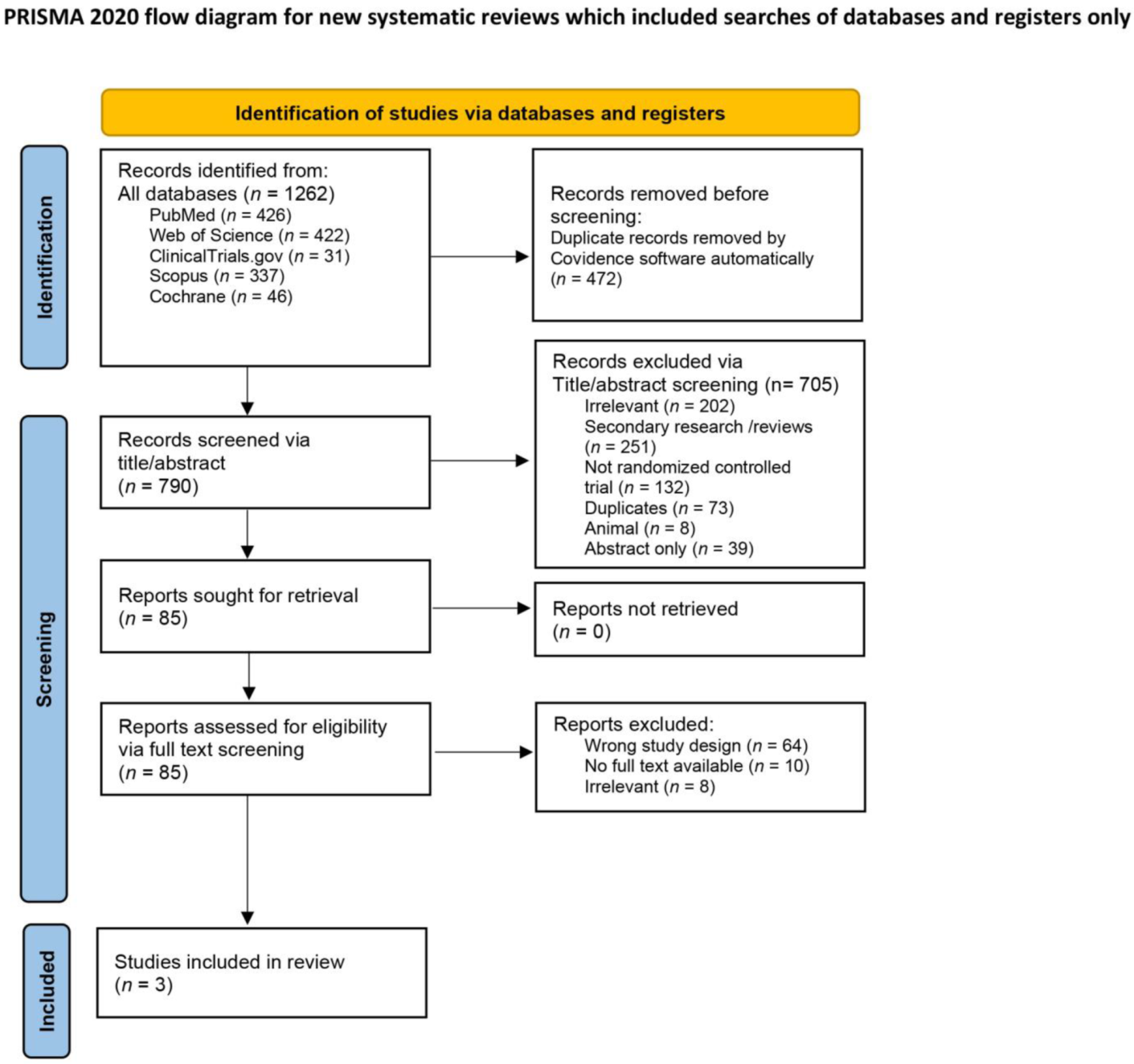

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias (ROB)

3.4. Outcomes of Interest

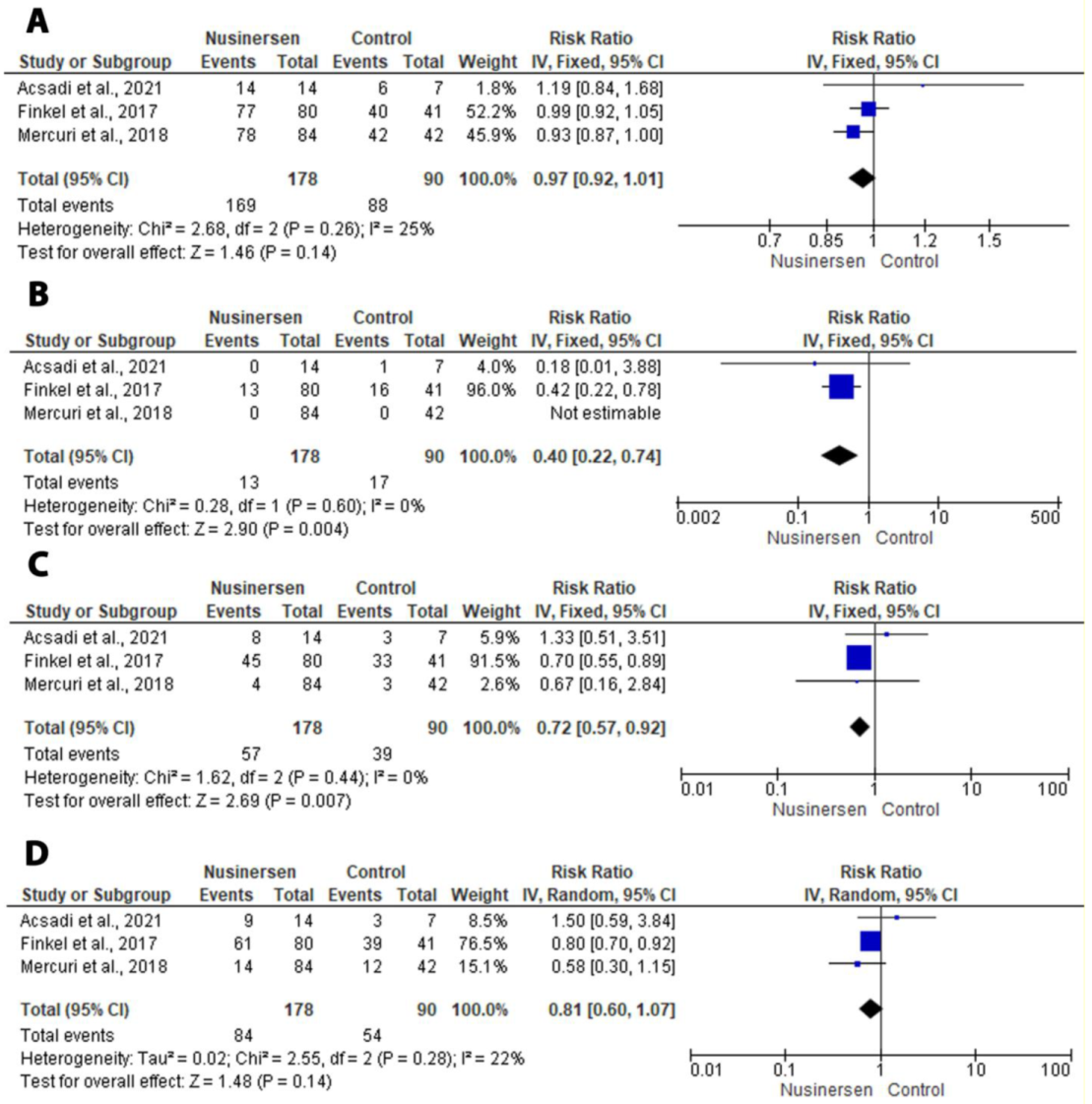

3.4.1. Primary Outcomes of Interest

3.4.2. Secondary Outcomes of Interest

4. Discussion

4.1. Safety and Efficacy of Nusinesen in SMA

4.2. Adverse Effects

4.3. Cost of Nusinersen

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kolb, S.J.; Kissel, J.T. Spinal muscular atrophy: A timely review. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lally, C.; Jones, C.; Farwell, W.; Reyna, S.P.; Cook, S.F.; Flanders, W.D. Indirect estimation of the prevalence of spinal muscular atrophy Type I, II, and III in the United States. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farrar, M.A.; Kiernan, M.C. The Genetics of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Progress and Challenges. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, R.S.; Weiner, D.J.; Mayer, O.H.; McDonough, J.M.; Panitch, H.B. Respiratory muscle function in infants with spinal muscular atrophy type I. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2014, 49, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, B.; Brichta, L.; Schrank, B.; Lochmüller, H.; Blick, S.; Baasner, A.; Heller, R. Mildly affected patients with spinal muscular atrophy are partially protected by an increased SMN2 copy number. Hum. Genet. 2006, 119, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchbach, M.E. Copy Number Variations in the Survival Motor Neuron Genes: Implications for Spinal Muscular Atrophy and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2016, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuscó, I.; Barceló, M.J.; del Rio, E.; Baiget, M.; Tizzano, E.F. Detection of novel mutations in the SMN Tudor domain in type I SMA patients. Neurology 2004, 63, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, T.W.; Swoboda, K.J.; Scott, H.D.; Hejmanowski, A.Q. Homozygous SMN1 deletions in unaffected family members and modification of the phenotype by SMN2. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2004, 130, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SMN1 Gene, Survival of Motor Neuron 1, Telomeric. 2020. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/smn1/ (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Lefebvre, S.; Bürglen, L.; Reboullet, S.; Clermont, O.; Burlet, P.; Viollet, L.; Benichou, B.; Cruaud, C.; Millasseau, P.; Zeviani, M.; et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell 1995, 80, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoy, S.M. Nusinersen: First Global Approval. Drugs 2017, 77, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acsadi, G.; Crawford, T.O.; Muller-Felber, W.; Shieh, P.B.; Richardson, R.; Natarajan, N.; Castro, D.; Ramirez-Schrempp, D.; Gambino, G.; Sun, P.; et al. Safety and efficacy of nusinersen in spinal muscular atrophy: The EMBRACE study. Muscle Nerve 2021, 63, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, R.S.; Mercuri, E.; Darras, B.T.; Connolly, A.M.; Kuntz, N.L.; Kirschner, J.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Saito, K.; Servais, L.; Tizzano, E.; et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Infantile-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sampson, M.; Shojania, K.G.; McGowan, J.; Daniel, R.; Rader, T.; Iansavichene, A.E.; Ji, J.; Ansari, M.T.; Moher, D. Surveillance search techniques identified the need to update systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. Endnote; Clarivate: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley Online Library: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hultcrantz, M.; Rind, D.; Akl, E.A.; Treweek, S.; Mustafa, R.A.; Iorio, A.; Alper, B.S.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Murad, M.H.; Ansari, M.T.; et al. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 87, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bishop, K.M.; Montes, J.; Finkel, R.S. Motor milestone assessment of infants with spinal muscular atrophy using the hammersmith infant neurological Exam-Part 2: Experience from a nusinersen clinical study. Muscle Nerve 2018, 57, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RevMan, Version 5.3; computer program; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014.

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercuri, E.; Darras, B.T.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Day, J.W.; Campbell, C.; Connolly, A.M.; Iannaccone, S.T.; Kirschner, J.; Kuntz, N.L.; Saito, K.; et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coratti, G.; Pane, M.; Lucibello, S.; Pera, M.C.; Pasternak, A.; Montes, J.; Sansone, V.A.; Duong, T.; Dunaway Young, S.; Messina, S.; et al. Age related treatment effect in type II Spinal Muscular Atrophy pediatric patients treated with nusinersen. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2021, 31, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vivo, D.C.; Bertini, E.; Swoboda, K.J.; Hwu, W.L.; Crawford, T.O.; Finkel, R.S.; Kirschner, J.; Kuntz, N.L.; Parsons, J.A.; Ryan, M.M.; et al. Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: Interim efficacy and safety results from the Phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2019, 29, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagenacker, T.; Wurster, C.D.; Gunther, R.; Schreiber-Katz, O.; Osmanovic, A.; Petri, S.; Weiler, M.; Ziegler, A.; Kuttler, J.; Koch, J.C.; et al. Nusinersen in adults with 5q spinal muscular atrophy: A non-interventional, multicentre, observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M.A.; Aria, D.J.; Schaefer, C.M.; Kaye, R.D.; Abruzzo, T.A.; Bernes, S.M.; Willard, S.D.; Riemann, M.C.; Towbin, R.B. A comprehensive institutional overview of intrathecal nusinersen injections for spinal muscular atrophy. Pediatr. Radiol. 2018, 48, 1797–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechmann, A.; Langer, T.; Schorling, D.; Eckenweiler, M.; Wider, S.; Kirschner, J. Single-Center Experience with Intrathecal Administration of Nusinersen in Children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type I. Neuropediatrics 2017, 48 , S1–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, M.; Hui, J.H.P.; Wong, H.K.; Chatterjee, A.; Lee, E.H. Spinal Fusion and Instrumentation for Paediatric Neuromuscular Scoliosis: Retrospective Review. J. Orthop. Surg. 2002, 10, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thokala, P.; Stevenson, M.; Kumar, V.M.; Ren, S.; Ellis, A.G.; Chapman, R.H. Cost effectiveness of nusinersen for patients with infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy in US. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2020, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga-Sanchez, S.; Teynor, M.; Knight, C.; Thompson, R.; Lundqvist, T.; Ekelund, M.; Forsmark, A.; Vickers, A.D.; Lloyd, A. Cost Effectiveness of Nusinersen in the Treatment of Patients with Infantile-Onset and Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy in Sweden. Pharmacoeconomics 2019, 37, 845–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jalali, A.; Rothwell, E.; Botkin, J.R.; Anderson, R.A.; Butterfield, R.J.; Nelson, R.E. Cost-Effectiveness of Nusinersen and Universal Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. J. Pediatr. 2020, 227, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhn, M.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Krause, M.; Samara, M.; Peter, N.; Arndt, T.; Bäckers, L.; Rothe, P.; Cipriani, A.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leucht, S.; Cipriani, A.; Spineli, L.; Mavridis, D.; Orey, D.; Richter, F.; Samara, M.; Barbui, C.; Engel, R.R.; Geddes, J.R.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: A multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013, 382, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.B.; Brašić, J.R. The role of lumateperone in the treatment of schizophrenia. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 11, 20451253211034019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanzman, A.M.; McDermott, M.P.; Montes, J.; Martens, W.B.; Flickinger, J.; Riley, S.; Quigley, J.; Dunaway, S.; O’Hagen, J.; Deng, L.; et al. Validation of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND). Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2011, 23, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzman, A.M.; Mazzone, E.; Main, M.; Pelliccioni, M.; Wood, J.; Swoboda, K.J.; Scott, C.; Pane, M.; Messina, S.; Bertini, E.; et al. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND): Test development and reliability. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2010, 20, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Finkel, R.S.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Vajsar, J.; Day, J.W.; Montes, J.; De Vivo, D.C.; Yamashita, M.; Rigo, F.; Hung, G.; Schneider, E.; et al. Treatment of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy with nusinersen: A phase 2, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet 2016, 388, 3017–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database Name | Search Terms | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | (CDR132l or nusinersen or IONIS-SMNRX or ISIS-SMNRX) and (spinal muscular atrophy or SMA) | 337 |

| PubMed | (CDR132l or nusinersen or IONIS-SMNRX or ISIS-SMNRX) and (spinal muscular atrophy or SMA) | 426 |

| Web of science | (CDR132l or nusinersen or IONIS-SMNRX or ISIS-SMNRX) and (spinal muscular atrophy or SMA) | 442 |

| Cochrane | (CDR132l or nusinersen or IONIS-SMNRX or ISIS-SMNRX) and (spinal muscular atrophy or SMA) | 46 |

| Clinicaltrials.gov | CDR132l or nusinersen or IONIS-SMNRX or ISIS-SMNRX | 31 |

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Population | Study Phase | Total Sample Size | Treatment (N) | Control (N) | Female Sex Treated by Nusinersen, N (%) | Type of SMA (N) | Median Age at Symptom Onset, Months | Median Age at Diagnosis, Months | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acsadi et al., 2021 (EMBRACE trial) [12] | USA and Germany | Double-blind RCT | Infants and young children | 2 | 21 | Nusinersen (14) | Sham in Part 1 (7)/ nusinersen in Part 2 (6) | 5 (36) | Infantile-onset (13)/ later-onset (8) | 5.3 | 10.6 | Both infantile and late-onset SMA showed a long-term benefit–risk ratio. No drug-related adverse effects or discontinuation due to the drug. Milestone improvement was 93% in the treatment group vs. 29% in the sham group. |

| Finkel et al., 2017 (ENDEAR trial) [13] | 31 global centers | Double-blind RCT | Infants | 3 | 121 | Nusinersen (80) | Sham (41) | 43 (54) | Infantile onset (121) | 2.1 (mean) | 3.5 (mean) | The treatment group had a higher probability of living longer. The hazard ratio for death was 0.53 vs. 0.37 in the sham group. Early treatment may be more beneficial for milestone improvement. |

| Mercuri et al., 2018 (CHERISH trial) [24] | 24 global centers | Double-blind RCT | Children | 3 | 126 | Nusinersen (84) | Sham (42) | 46 (55) | Later-onset (126) | 10.3 | 18 | There was a significant improvement regarding milestones in late-onset SMA. Adverse effects were similar in both groups, but there was a higher improvement in the HFMSE score in the treatment group vs. sham. |

| Author, Year | Treatment (N) | Pyrexia | Vomiting | Constipation | Cough | Upper-Respiratory-Tract Infection | Pneumonia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N) | |||||||

| Acsadi et al., 2021 (EMBRACE trial) [12] | Nusinersen (14) | 12 | 8 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 9 |

| Sham (7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Finkel et al., 2017 (ENDEAR trial) [13] | Nusinersen (80) | 45 | 14 | 28 | 9 | 24 | 23 |

| Sham (41) | 24 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 7 | |

| Mercuri et al., 2018 (CHERISH trial) [24] | Nusinersen (84) | 36 | 24 | 1 | 21 | 25 | 2 |

| Sham (42) | 15 | 5 | 0 | 9 | 19 | 6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbas, K.S.; Eltaras, M.M.; El-Shahat, N.A.; Abdelazeem, B.; Shaqfeh, M.; Brašić, J.R. The Safety and Efficacy of Nusinersen in the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina 2022, 58, 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58020213

Abbas KS, Eltaras MM, El-Shahat NA, Abdelazeem B, Shaqfeh M, Brašić JR. The Safety and Efficacy of Nusinersen in the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina. 2022; 58(2):213. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58020213

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Kirellos Said, Mennatullah Mohamed Eltaras, Nahla Ahmed El-Shahat, Basel Abdelazeem, Mahmoud Shaqfeh, and James Robert Brašić. 2022. "The Safety and Efficacy of Nusinersen in the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Medicina 58, no. 2: 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58020213

APA StyleAbbas, K. S., Eltaras, M. M., El-Shahat, N. A., Abdelazeem, B., Shaqfeh, M., & Brašić, J. R. (2022). The Safety and Efficacy of Nusinersen in the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina, 58(2), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58020213