How Telemedicine Can Improve the Quality of Care for Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias? A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

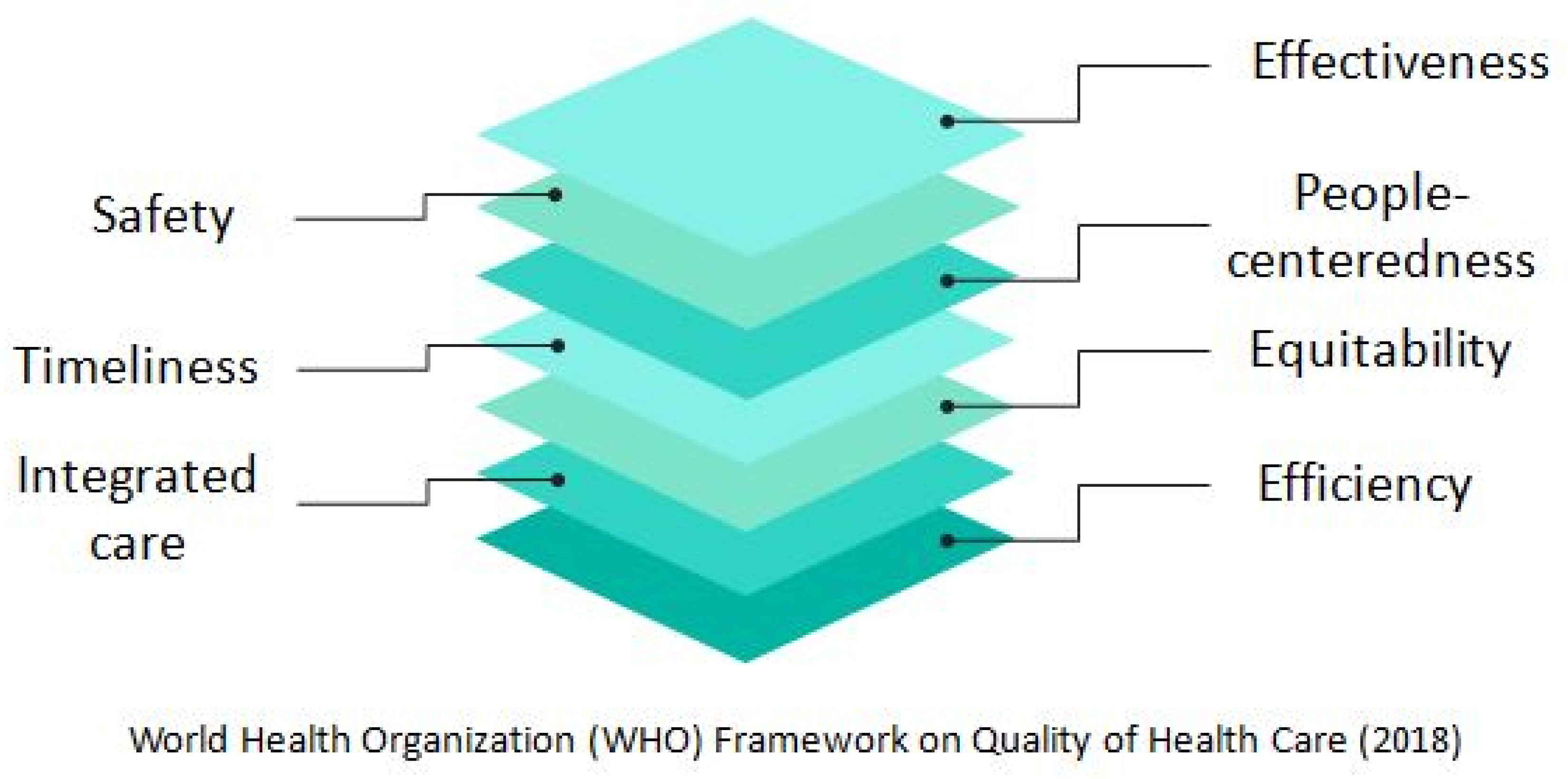

3.1. Defining the Concept and Dimensions of Healthcare Quality

3.2. Definition and Primary Forms of Telemedicine

3.3. The Reliability of Telemedicine in AD and Related Dementias

3.4. Quality of Care for AD and Related Dementias and the Emerging Role of Telemedicine: Current Evidence

3.4.1. Effectiveness

3.4.2. Safety

3.4.3. People-Centeredness

3.4.4. Timeliness

3.4.5. Equitability

3.4.6. Integrated Care

3.4.7. Efficiency

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emmady, P.D.; Tadi, P. Dementia; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintola, A.A.; Achterberg, W.P.; Caljouw, M.A.A. Non-pharmacological interventions for improving quality of life of long-term care residents with dementia: Ascoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A.; Kunik, M.E.; Schulz, P.; Williams, S.P.; Singh, H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: Prevalenceand contributing factors. AlzheimerDis. Assoc. Disord. 2009, 23, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.M.; Goh, A.M.Y.; Mocellin, R.; Malpas, C.B.; Parker, S.; Eratne, D.; Farrand, S.; Kelso, W.; Evans, A.; Walterfang, M.; et al. Time to diagnosis in younger-onset dementia and the impact of a specialist diagnostic service. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2022, 34, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, D.B.; Evertson, L.C.; Wenger, N.S.; Serrano, K.; Chodosh, J.; Ercoli, L.; Tan, Z.S. The University of California at Los Angeles Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care program for comprehensive, coordinated, patient-centered care: Preliminary data. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 2214–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.L.; Myers, T.L.; Waddell, E.M.; Spear, K.L.; Schneider, R.B. Telemedicine: A valuable tool in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2020, 9, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosse, P.J.; Kassardjian, C.D.; Masellis, M.; Mitchell, S.B. Virtual care for patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias during the COVID-19 era and beyond. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. = J. L’association Med. Can. 2021, 193, E371–E377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortmann, M. Dementia: A global health priority—Highlights from an ADI and World Health Organization report. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2012, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkodo, J.A.; Gana, W.; Debacq, C.; Aidoud, A.; Poupin, P.; Camus, V.; Fougere, B. The Role of Telemedicine in the Management of the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2022, 30, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serper, M.; Volk, M.L. Currentand Future Applications of Telemedicine to Optimize the Delivery of Carein Chronic Liver Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2018, 16, 157–161.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, D.E.; Hamlet, K.M.; Bauer, R.M.; Bowers, D. Validity of teleneuropsychology for older adults in response to COVID-19: A systematic and critical review. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 34, 1411–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.S.; Pittman, C.A.; Price, C.L.; Nieman, C.L.; Oh, E.S. Telemedicine and Dementia Care: A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1396–1402.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dequanter, S.; Gagnon, M.P.; Ndiaye, M.A.; Gorus, E.; Fobelets, M.; Giguere, A.; Bourbonnais, A.; Buyl, R. The Effectiveness of e-Health Solutions for Aging with Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2021, 61, e373–e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Handbook for National Quality Policy and Strategy: A Practical Approach for Developing Policy and Strategy to Improve Quality of Care. Geneva. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565561 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: Ananalysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sataloff, R.T.; Bush, M.L.; Chandra, R.; Chepeha, D.; Rotenberg, B.; Fisher, E.W.; Goldenberg, D.; Hanna, E.Y.; Kerschner, J.E.; Kraus, D.H.; et al. Systematic and other reviews: Criteria and complexities. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 7, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresford, C.J.; Kozlowska, O. The barriers and facilitators to managing diabetes with insulinin adults with intellectual disabilities: A systemised review of the literature. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. JARID 2022, 35, 1253–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Peacock, R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. BMJ 2005, 331, 1064–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IOM. Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi, N.; Weinstein, R.S.; Stewart, K.; Doarn, C.R. Analysis of Telehealth Versus Telemedicine Terminologyin the Telemedicine and e-Health Journal between 2010 and 2020. Telemed. J. E-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichloo, A.; Albosta, M.; Dettloff, K.; Wani, F.; El-Amir, Z.; Singh, J.; Aljadah, M.; Chakinala, R.C.; Kanugula, A.K.; Solanki, S.; et al. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: A narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, X.; Yu, H.; Cui, L. Application of Telemedicine in COVID-19: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 908756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotenuto, A.; Rea, R.; Traini, E.; Ricci, G.; Fasanaro, A.M.; Amenta, F. Cognitive Assessment of Patients with Alzheimer’s Diseaseby Telemedicine: Pilot Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeYoung, N.; Shenal, B.V. The reliability of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment using telehealth in a rural setting with veterans. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindauer, A.; Seelye, A.; Lyons, B.; Dodge, H.H.; Mattek, N.; Mincks, K.; Kaye, J.; Erten-Lyons, D. Dementia Care Comes Home: Patient and Caregiver Assessment via Telemedicine. Gerontologist 2017, 57, e85–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galusha-Glasscock, J.M.; Horton, D.K.; Weiner, M.F.; Cullum, C.M. Video Teleconference Administration of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. Off. J. Natl. Acad. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahia, I.V.; Ng, B.; Camacho, A.; Cardenas, V.; Cherner, M.; Depp, C.A.; Palmer, B.W.; Jeste, D.V.; Agha, Z. Telepsychiatry for Neurocognitive Testingin Older Rural Latino Adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadsworth, H.E.; Dhima, K.; Womack, K.B.; Hart, J., Jr.; Weiner, M.F.; Hynan, L.S.; Cullum, C.M. Validity of Teleneuropsychological Assessmentin Older Patients with Cognitive Disorders. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. Off. J. Natl. Acad. Neuropsychol. 2018, 33, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestal, L.; Smith-Olinde, L.; Hicks, G.; Hutton, T.; Hart, J., Jr. Efficacy of language assessment in Alzheimer’s disease: Comparing in-person examination and telemedicine. Clin. Interv. Aging 2006, 1, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, K.; De Silva, A.; Simpson, J.A.; LoGiudice, D.; Engel, L.; Gilbert, A.S.; Croy, S.; Haralambous, B. Video-interpreting for cognitive assessments: An intervention study and micro-costing analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2022, 28, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakis, M.K.; Papadopoulos, F.C.; Beratis, I.; Michelakos, T.; Kanavidis, P.; Dafermos, V.; Tousoulis, D.; Papageorgiou, S.G.; Petridou, E.T. Validation of TICS for detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment among individuals characterized by low levels of education or illiteracy: A population-based study in rural Greece. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2017, 31, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doraiswamy, S.; Jithesh, A.; Mamtani, R.; Abraham, A.; Cheema, S. Telehealth Usein Geriatrics Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Scoping Review and Evidence Synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L.A.; Tan, Z.; Wenger, N.S.; Cook, E.A.; Han, W.; McCreath, H.E.; Serrano, K.S.; Roth, C.P.; Reuben, D.B. Quality of Care Provided by a Comprehensive Dementia Care Comanagement Program. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 1724–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, S.F.; Ferguson, D. Autoimmune Encephalitidesand Rapidly Progressive Dementias. Semin. Neurol. 2019, 39, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calil, V.; Elliott, E.; Borelli, W.V.; Barbosa, B.; Bram, J.; Silva, F.O.; Cardoso, L.G.M.; Mariano, L.I.; Dias, N.; Hornberger, M.; et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of dementia: Insights from the United Kingdom-Brazil Dementia Workshop. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2020, 14, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghari, R.; Guerchouche, R.; TranDuc, M.; Bremond, F.; Lemoine, M.P.; Bultingaire, V.; Langel, K.; DeGroote, Z.; Kuhn, F.; Martin, E.; et al. Pilot Study to Assess the Feasibility of a Mobile Unitfor Remote Cognitive Screening of Isolated Elderlyin Rural Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickrey, B.G.; Mittman, B.S.; Connor, K.I.; Pearson, M.L.; DellaPenna, R.D.; Ganiats, T.G.; Demonte, R.W., Jr.; Chodosh, J.; Cui, X.; Vassar, S.; et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodosh, J.; Mittman, B.S.; Connor, K.I.; Vassar, S.D.; Lee, M.L.; DeMonte, R.W.; Ganiats, T.G.; Heikoff, L.E.; Rubenstein, L.Z.; DellaPenna, R.D.; et al. Caring for patients with dementia: How good is the quality of care? Results from thre ehealth systems. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodosh, J.; Pearson, M.L.; Connor, K.I.; Vassar, S.D.; Kaisey, M.; Lee, M.L.; Vickrey, B.G. A dementia care management intervention: Which components improve quality? Am. J. Manag. Care 2012, 18, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, L.; Jones, S.C.; Magee, C. A review of the factors associated with the non-use of respite services by carers of people with dementia: Implications for policy and practice. HealthSoc. Care Community 2014, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, S.; Cinalioglu, K.; Sekhon, K.; Gruber, J.; Rigas, C.; Bodenstein, K.; Naghi, K.; Lavin, P.; Greenway, K.T.; Vahia, I.; et al. A Systematic Review of Telemedicine for Older Adults with Dementia During COVID-19: An Alternativeto In-person Health Services? Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 761965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, A.; Iliffe, S.; Gaehl, E.; Campbell, S.; Drake, R.; Morris, J.; Martin, H.; Purandare, N. Quality of care provided to people with dementia: Utilisation and quality of the annual dementia reviewin general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 2012, 62, e91–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossey, J.; Ballard, C.; Juszczak, E.; James, I.; Alder, N.; Jacoby, R.; Howard, R. Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: Cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2006, 332, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Linkletter, C.; Dore, D.; Mor, V.; Buka, S.; Maclure, M. Age, antipsychotics, and the risk of ischemicstrokein the Veterans Health Administration. Stroke 2012, 43, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias-Guiu, J.A.; Pytel, V.; Matias-Guiu, J. Death Rate Dueto COVID-19 in Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2020, 78, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, C.M.; Boustani, M.A.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Austrom, M.G.; Damush, T.M.; Perkins, A.J.; Fultz, B.A.; Hui, S.L.; Counsell, S.R.; Hendrie, H.C. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 2148–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boustani, M.A.; Sachs, G.A.; Alder, C.A.; Munger, S.; Schubert, C.C.; GuerrieroAustrom, M.; Hake, A.M.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Farlow, M.; Matthews, B.R.; et al. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging Ment. Health 2011, 15, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, J.E.; Valois, L.; Zweig, Y. Collaborative trans disciplinary team approach for dementia care. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2014, 4, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, K.; Liu, E.; Clemson, L.; Davies, O.; Gray, L.; Gitlin, L.N.; Crotty, M. Does Telehealth Delivery of a Dyadic Dementia Care Program Provide a Noninferior Alternative to Face-To-Face Delivery of the Same Program? A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russ, T.C.; Batty, G.D.; Hearnshaw, G.F.; Fenton, C.; Starr, J.M. Geographical variation in dementia: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 1012–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarchi, F.; Contaldi, E.; Magistrelli, L.; Cantello, R.; Comi, C.; Mazzini, L. Telehealth in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Opportunities and Challenges for Patients and Physicians. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolluri, S.; Stead, T.S.; Mangal, R.K.; Coffee, R.L., Jr.; Littell, J.; Ganti, L. Telehealth in Response to the Rural Health Disparity. Health Psychol. Res. 2022, 10, 37445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.J.; Daly, A.T.; Olchanski, N.; Cohen, J.T.; Neumann, P.J.; Faul, J.D.; Fillit, H.M.; Freund, K.M. Dementia Diagnosis Disparities by Raceand Ethnicity. Med. Care 2021, 59, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, D.L.; Vickrey, B.G.; Schwankovsky, L.; Heck, E.; Plauchm, M.; Yep, R. Interventions to improve quality of care: The Kaiser Permanente-alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Project. Am. J. Manag. Care 2004, 10, 553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben, D.B.; Roth, C.P.; Frank, J.C.; Hirsch, S.H.; Katz, D.; McCreath, H.; Younger, J.; Murawski, M.; Edgerly, E.; Maher, J.; et al. Assessing care of vulnerable elders—Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study of a practice redesign intervention to improve the quality of dementia care. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Gamez, N.; Alliance, S.; Majid, T.; Taylor, A.S.; Kurasz, A.M.; Patel, B.; Smith, G.E. Clinical Careand Unmet Needs of Individuals with Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Caregivers: An Interview Study. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2021, 35, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, D.A.; Koretz, B.K.; Bail, J.K.; McCreath, H.E.; Wenger, N.S.; Roth, C.P.; Reuben, D.B. Nurse practitioner comanagement for patients in an academic geriatric practice. Am. J. Manag. Care 2010, 16, e343–e355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Litaker, D.; Mion, L.; Planavsky, L.; Kippes, C.; Mehta, N.; Frolkis, J. Physician-nurse practitioner team sinchronic disease management: The impacton costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients’ perception of care. J. Interprof. Care 2003, 17, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, F.H.; Yan, E.W.; Yu, K.K.; Tsui, W.S.; Chan, D.T.; Yee, B.K. The Protective Impact of Telemedicineon Persons with Dementia and Their Care givers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, S.; Mauskopf, J.; Kriza, C.; Wahlster, P.; Kolominsky-Rabas, P.L. The main cost drivers in dementia: A systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.S.; Buckner, J. Reaching Outto Rural Caregivers and Veterans with Dementia Utilizing Clinical Video-Telehealth. Geriatr. 2018, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Jhoo, J.H.; Jang, J.W. Theeffectoftelemedicineoncognitivedeclineinpatientswith Dementia. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.; Roques, P.K.; Fox, N.C.; Rossor, M.N. CANDID—Counselling and Diagnosisin Dementia: A national telemedicine service supporting the care of younger patients with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1998, 13, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Homer, M.; Rossi, M.I. Use of Clinical Video Telehealthasa Toolfor Optimizing Medications for Rural Older Veterans with Dementia. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, A.; Pressat-Laffouilhere, T.; Sarazin, M.; Lagarde, J.; Roue-Jagot, C.; Olivieri, P.; Paquet, C.; Cognat, E.; Dumurgier, J.; Pasquier, F.; et al. Telemedicine in French Memory Clinics during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2022, 86, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, C.K.; Lim, K.H.; Jang, J.W.; Jhoo, J.H. The effect of telemedicine on the duration of treatment in dementia patients. J. Telemed. Telecare 2015, 21, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, N.; Amos, S.; Milne, K.; Power, B. Telemedicine in a rural memory disorder clinic—Remote management of patients with dementia. Can. Geriatr. J. CGJ 2012, 15, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, A.P.; Ballard, C.; Beigi, M.; Kalafatis, C.; Brooker, H.; Lavelle, G.; Bronnick, K.K.; Sauer, J.; Boddington, S.; Velayudhan, L.; et al. Implementing Remote Memory Clinicsto Enhance Clinical Care during and after COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capozzo, R.; Zoccolella, S.; Frisullo, M.E.; Barone, R.; Dell’Abate, M.T.; Barulli, M.R.; Musio, M.; Accogli, M.; Logroscino, G. Telemedicine for Delivery of Care in Fronto temporal Lobar Degeneration during COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from Southern Italy. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2020, 76, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, S.M.; Wasserman, E.B.; Wood, N.E.; Wang, H.; Dozier, A.; Nelson, D.; McConnochie, K.M.; Shah, M.N. High-Intensity Telemedicine Reduces Emergency Department Useby Older Adults with Dementia in Senior Living Communities. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 942–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.N.; Wasserman, E.B.; Gillespie, S.M.; Wood, N.E.; Wang, H.; Noyes, K.; Nelson, D.; Dozier, A.; McConnochie, K.M. High-Intensity Telemedicine Decreases Emergency Department Use for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditionsby Older Adult Senior Living Community Residents. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclater, K.; Alagiakrishnan, K.; Sclater, A. An investigation of video conferenced geriatric medicine grand round sin Alberta. J. Telemed. Telecare 2004, 10, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, B.B.; Homer, M.C.; Morone, N.; Edmonds, N.; Rossi, M.I. Creation of an Interprofessional Teledementia Clinic for Rural Veterans: Preliminary Data. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gately, M.E.; Trudeau, S.A.; Moo, L.R. Feasibility of Telehealth-Delivered Home Safety Evaluations for Caregivers of Clients with Dementia. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2020, 40, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, S.; Gomez-Orozco, C.A.; van Zuilen, M.H.; Levis, S. Providing Dementia Consultationsto Veterans Using Clinical Video Telehealth: Results from a Clinical Demonstration Project. Telemed. J. E-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2018, 24, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozian, M.; Mohammadian, F. Lessons from COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical experiences on Telemedicine in patients with dementia in Iran. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2021, 17 (Suppl. 8), e057468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, D.P.; Queiroz, I.B.; Carneiro, A.H.S.; Pereira, D.A.A.; Castro, C.S.; Viana-Junior, A.B.; Nogueira, C.B.; CoelhoFilho, J.M.; Lobo, R.R.; Roriz-Filho, J.S.; et al. Feasibility indicators of telemedicine for patients with dementia in a public hospital in Northeast Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira-Constantin, B.; Carpen-Padovani, G.; Cordeiro-Gaede, A.V.; Chamma-Coelho, A.; Martinez-Souza, R.K.; Nisihara, R. Telemedicine in themonitoringofpatients with dementia:ABrazilianscaregivers’sperspective. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 74, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moo, L.R.; Gately, M.E.; Jafri, Z.; Shirk, S.D. Home-Based Video Telemedicine for Dementia Management. Clin. Gerontol. 2020, 43, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardach, S.H.; Gibson, A.; Parsons, K.; Stauffer, A.; Jicha, G.A. Rural Caregivers: Identification of Informational Needs through Telemedicine Questions. J. Rural Health Off. J. Am. RuralHealthAssoc. Natl. RuralHealthCareAssoc. 2021, 37, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuijt, R.; Rait, G.; Frost, R.; Wilcock, J.; Manthorpe, J.; Walters, K. Remote primary care consultations for people living with Dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of people living with Dementia and their carers. Br. J. Gen. Pract. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, e574–e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Mehta, P.; Weith, J.; Hoang-Gia, D.; Moore, J.; Carlson, C.; Choe, P.; Sakai, E.; Gould, C. Converting a Geriatrics Clinicto Virtual Visits during COVID-19: A Case Study. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 21501327211000235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, R.; Bradley, R.; Harper, E.; Davies, L.; Pank, L.; Lam, N.; Davies, A.; Talbot, E.; Hooper, E.; Winson, R.; et al. Assistive technology and telecare to maintain independent living athome for people with Dementia: The ATTILARCT. Health Technol. Assess. 2021, 25, 1–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamani, M.; McDonald, L.; SaezAguayo, I.; Kanios, C.; Katsanou, M.N.; Madeley, L.; Limousin, P.D.; Lees, A.J.; Haritou, M.; Jahanshahi, M.; et al. A randomized controlled pilot study to evaluateate chnology platform for the assisted living of people with Dementia and their carers. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2014, 41, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tso, J.V.; Farinpour, R.; Chui, H.C.; Liu, C.Y. A Multidisciplinary Model of Dementia Careinan Underserved Retirement Community, Made Possible by Telemedicine. Front. Neurol. 2016, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perri, G.A.; Abdel-Malek, N.; Bandali, A.; Grosbein, H.; Gardner, S. Early integration of palliative care in a long-term carehome: A telemedicin efeasibility pilot study. Palliat. Supportive Care 2020, 18, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, D.G.; Crossley, M.; Kirk, A.; D’Arcy, C.; Stewart, N.; Biem, J.; Forbes, D.; Harder, S.; Basran, J.; DalBello-Haas, V.; et al. Improving access to dementia care: Development and evaluation of a rural and remote memory clinic. AgingMent. Health 2009, 13, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coley, N.; Andre, L.; Hoevenaar-Blom, M.P.; Ngandu, T.; Beishuizen, C.; Barbera, M.; van Wanrooij, L.; Kivipelto, M.; Soininen, H.; van Gool, W.; et al. Factors Predicting Engagement of Older Adults with a Coach-Supported eHealth Intervention Promoting Lifestyle Change and Associations between Engagement and Changes in Cardiovascular and Dementia Risk: Secondary Analysis of an 18-Month Multinational Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e32006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMonica, H.M.; English, A.; Hickie, I.B.; Ip, J.; Ireland, C.; West, S.; Shaw, T.; Mowszowski, L.; Glozier, N.; Duffy, S.; et al. Examining Internetande Health Practices and Preferences: Survey Study of Australian Older Adults with Subjective Memory Complaints, Mild Cognitive Impairment, or Dementia. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, B.; Zippel-Schultz, B.; Popa, A.; Hellrung, N.; Szczesny, S.; Moller, C.; Schultz, C.; Haux, R. CASEPLUS-SimPat: An Intersectoral Web-Based Case Management System for Multimorbid Dementia Patients. J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepke, C.; Shaughnessy, L.W.; Brunton, S.; Farmer, J.G.; Rosenzweig, A.S.; Grossberg, G.T.; Wright, W.L. Using Telemedicine to Assessand Manage Psychosis Among Outpatients with Neurodegenerative Disease. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 10271–10280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, E.F.; Malik, R.; Santos, T.; Ceide, M.; Cohen, J.; Verghese, J.; Zwerling, J.L. Telehealth for the cognitively impaired older adult and their caregivers: Lessons from acoordinated approach. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2021, 11, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pond, D.; Higgins, I.; Mate, K.; Merl, H.; Mills, D.; McNeil, K. Mobile memory clinic: Implementing a nurse practitioner-led, collaborative dementia model of care with in general practice. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2021, 27, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, L.; Brunton, S.; Chepke, C.; Farmer, J.G.; Rosenzweig, A.S.; Grossberg, G. Using Telemedicine to Assessand Manage Psychosis in Neurodegenerative Diseases in Long-Term Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.L.; O’Connell, M.E. Telehealth Rehabilitation for Cognitive Impairment: Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotelli, M.; Manenti, R.; Brambilla, M.; Gobbi, E.; Ferrari, C.; Binetti, G.; Cappa, S.F. Cognitivetele rehabilitation in mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and fron to temporal dementia: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernini, S.; Stasolla, F.; Panzarasa, S.; Quaglini, S.; Sinforiani, E.; Sandrini, G.; Vecchi, T.; Tassorelli, C.; Bottiroli, S. Cognitive Telerehabilitation for Older Adults with Neuro degenerative Diseases in the COVID-19 Era: A Perspective Study. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 623933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, R.; O’Connell, M.E.; Morgan, D.G. Exploring interestand goals for vide oconferencing delivered cognitive rehabilitation with rural individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Neuro Rehabil. 2016, 39, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar-Fuchs, A.; Webb, S.; Bartsch, L.; Clare, L.; Rebok, G.; Cherbuin, N.; Anstey, K.J. Tailored and Adaptive Computerized Cognitive Training in Older Adults at Risk for Dementia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2017, 60, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.; Owen, A.; Hampshire, A.; Grahn, J.; Stenton, R.; Dajani, S.; Burns, A.; Howard, R.; Williams, N.; Williams, G.; et al. The Effect of an Online Cognitive Training Package in Healthy Older Adults: An Online Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelcic, N.; Agostini, M.; Meneghello, F.; Busse, C.; Parise, S.; Galano, A.; Tonin, P.; Dam, M.; Cagnin, A. Feasibility and efficacy of cognitive tele rehabilitation in early Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dial, H.R.; Hinshelwood, H.A.; Grasso, S.M.; Hubbard, H.I.; Gorno-Tempini, M.L.; Henry, M.L. Investigating the utility of teletherapy in individuals with primary progressive aphasia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getz, H.; Snider, S.; Brennan, D.; Friedman, R. Successful remote delivery of a treatment for phonological a lexiavia telerehab. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2016, 26, 584–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, M.; Campbell, K.; Jennings, M.; Montero-Odasso, M.; Orange, J.B.; Knowlton, J.; StGeorge, A.; Bryant, D. Virtual Reality Experience Intervention May Reduce Responsive Behaviorsin Nursing Home Residents with Dementia: A Case Series. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2021, 84, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimelow, R.E.; Dawe, B.; Dissanayaka, N. Preliminary Research: Virtual Reality in Residential Aged Careto Reduce Apathy and Improve Mood. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cunha, N.M.; Nguyen, D.; Naumovski, N.; McKune, A.J.; Kellett, J.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Frost, J.; Isbel, S. A Mini-Review of Virtual Reality-Based Interventions to Promote Well-Being for People Living with Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Gerontology 2019, 65, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DalBello-Haas, V.P.; O’Connell, M.E.; Morgan, D.G.; Crossley, M. Lessons learned: Feasibility and acceptability of a telehealth-delivered exercise intervention for rural-dwelling individuals with Dementia and their caregivers. Rural Remote Health 2014, 14, 2715. [Google Scholar]

- Ptomey, L.T.; Vidoni, E.D.; Montenegro-Montenegro, E.; Thompson, M.A.; Sherman, J.R.; Gorczyca, A.M.; Greene, J.L.; Washburn, R.A.; Donnelly, J.E. The Feasibility of Remotely Delivered Exercise Sessionin Adults with Alzheimer’s Diseaseand Their Caregivers. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damianakis, T.; Wilson, K.; Marziali, E. Family caregiver support groups: Spiritual reflections’ impacton stress management. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.C.; Kovaleva, M.; Higgins, M.; Langston, A.H.; Hepburn, K. Tele-Savvy: An Online Program for Dementia Caregivers. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2018, 33, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindauer, A.; Croff, R.; Mincks, K.; Mattek, N.; Shofner, S.J.; Bouranis, N.; Teri, L. “It Took the Stress out of Getting Help”: The STAR-C-Telemedicine Mixed Methods Pilot. Care Wkly. 2018, 2, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, G.; Rose, T.; Crystal, L. Using videoconsultations to support family carers of people living with Dementia. Nurs. Older People 2022, 34, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindauer, A.; Messecar, D.; McKenzie, G.; Gibson, A.; Wharton, W.; Bianchi, A.; Tarter, R.; Tadesse, R.; Boardman, C.; Golonka, O.; et al. The Tele-STELLA protocol: Telehealth-based support for families living with later-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4254–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaugler, J.E.; Statz, T.L.; Birkeland, R.W.; Louwagie, K.W.; Peterson, C.M.; Zmora, R.; Emery, A.; McCarron, H.R.; Hepburn, K.; Whitlatch, C.J.; et al. The Residential Care Transition Module: A single-blinded randomized controlled evaluation of a telehealth support intervention for family care givers of persons with Dementia living in residential long-term care. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, C.A.; Williams, K.N.; Perkhounkova, Y.; Hein, M.; Coleman, C.K. Effects of a Video-based Interventionon Caregiver Confidence for Managing Dementia Care Challenges: Findings from the Fam Tech Care Clinical Trial. Clin. Gerontol. 2020, 43, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.N.; Perkhounkova, Y.; Shaw, C.A.; Hein, M.; Vidoni, E.D.; Coleman, C.K. Supporting Family Caregivers with Technology for Dementia Home Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Innov. Aging 2019, 3, igz037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, A.M.; Gant, J.R. A telehealth behavioral coaching intervention for neurocognitive disorder family carers. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattink, B.; Meiland, F.; van der Roest, H.; Kevern, P.; Abiuso, F.; Bengtsson, J.; Giuliano, A.; Duca, A.; Sanders, J.; Basnett, F.; et al. Web-Based STARE-Learning Course Increases Empathy and Understanding in Dementia Care givers: Results froma Randomized Controlled Trial in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, M.E.; Crossley, M.; Cammer, A.; Morgan, D.; Allingham, W.; Cheavins, B.; Dalziel, D.; Lemire, M.; Mitchell, S.; Morgan, E. Development and evaluation of a telehealth videoconferenced support group for rural spouses of individuals diagnosed with a typical early-onset dementias. Dementia 2014, 13, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forducey, P.G.; Glueckauf, R.L.; Bergquist, T.F.; Maheu, M.M.; Yutsis, M. Tele health for persons with severe functional disabilities and their caregivers: Facilitating self-care management in the homesetting. Psychol. Serv. 2012, 9, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, D.F.; Tarlow, B.J.; Jones, R.N. Effects of an automated telephone support system on caregiver burden and anxiety: Findings from the REACHforTLC intervention study. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisdorfer, C.; Czaja, S.J.; Loewenstein, D.A.; Rubert, M.P.; Arguelles, S.; Mitrani, V.B.; Szapocznik, J. The effect of a family therapy and technology-based interventionon caregiver depression. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, E.; McDarby, M.; Pagano, I.; Llaneza, D.; Owen, J.; Duberstein, P. The feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an mHealth mindfulness therapy for caregivers of adults with cognitive impairment. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 1963–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, J.D.; Sperling, S.A.; Brown, D.S.; Mittleman, M.S.; Manning, C.A. Evaluating the efficacy of Tele FAMILIES: A telehealth intervention for caregivers of community-dwelling people with Dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banbury, A.; Parkinson, L.; Gordon, S.; Wood, D. Implementing a peer-support programme by group videoconferencing for isolated carers of people with Dementia. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, S.; Marinova-Schmidt, V.; Gobin, J.; Criegee-Rieck, M.; Griebel, L.; Engel, S.; Stein, V.; Graessel, E.; Kolominsky-Rabas, P.L. Tailorede-Health services for the dementia caresetting: A pilot studyof ‘eHealthMonitor’. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilz, G.; Reder, M.; Meichsner, F.; Soellner, R. The Tele. T An Dem Intervention: Telephone-based CBT for Family Caregivers of People with Dementia. Gerontologist 2018, 58, e118–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.J.; Curtis, A.F.; Rowe, M.A.; McCrae, C.S. Using Telehealth to Deliver Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of I nsomnia to a Caregiver of a Person with Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2022, 36, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.N.; Shaw, C.A.; Perkhounkova, Y.; Hein, M.; Coleman, C.K. Satisfaction, utilization, and feasibility of a telehealth intervention for in-home dementia care support: A mixed methods study. Dementia 2021, 20, 1565–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.W.D.; Lindauer, A.; Kaye, J. EVALUATE-AD and Tele-STAR: Novel Methodologies for Assessment of Caregiver Burden in a Telehealth Caregiver Intervention—A Case Study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2019, 47, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Brini, S.; Hirani, S.; Gathercole, R.; Forsyth, K.; Henderson, C.; Bradley, R.; Davies, L.; Dunk, B.; Harper, E.; et al. The impact of assistive technology on burden and psychological well-being in informal caregivers of people with Dementia (ATTILA Study). Alzheimers Dement. NY 2020, 6, e12064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AltunkalemSeydi, K.; AtesBulut, E.; Yavuz, I.; Kavak, H.; Kaya, D.; Isik, A.T. E-mail-based health care in patients with dementia during the pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 863923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comans, T.A.; Martin-Khan, M.; Gray, L.C.; Scuffham, P.A. A break-even analysis of delivering a memory clinic by videoconferencing. J. Telemed. Telecare 2013, 19, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, C.A.; Williams, K.N.; Lee, R.H.; Coleman, C.K. Cost-effectiveness of a telehealth intervention for in-home dementia care support: Findings from the Fam Tech Care clinical trial. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, L.O.; Shulan, M.D.; Toseland, R.W.; Freeman, K.E.; Vasquez, B.E.; Gao, J. The effect of telephone support groups on costs of care for veterans with Dementia. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, P.; Hui, E.; Dai, D.; Kwok, T.; Woo, J. Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory problems: Telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Jhoo, J.H.; Lee, K.U.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, D.Y.; Woo, J.I. A telemedicine system as a care modality for dementia patients in Korea. AlzheimerDis. Assoc. Disord. 2000, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shores, M.M.; Ryan-Dykes, P.; Williams, R.M.; Mamerto, B.; Sadak, T.; Pascualy, M.; Felker, B.L.; Zweigle, M.; Nichol, P.; Peskind, E.R. Identifying undiagnosed dementia in residential care veterans: Comparing telemedicine to in-person clinical examination. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 19, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, W.B.; Silvestre, I.T.; Lima, A.M.O.; de Almondes, K.M. The Influence of Telemedicine Careon the Management of Behavioral and Psychological Symptomsin Dementia (BPSD) Risk Factors Inducedor Exacerbated during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 577629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, E.A.; Borson, S.; Grothaus, L.; Balch, S.; Larson, E.B. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA 2012, 307, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.S.; Marcantonio, E.R.; McCarthy, E.P.; Herzig, S.J. National Trendsin Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations of Older Adults with Dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2240–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J.M.; VanHoutven, C.H.; Sleath, B.L.; Thorpe, C.T. Rural-urban differences in preventable hospitalizations among community-dwelling veterans with Dementia. J. Rural Health Off. J. Am. Rural Health Assoc. Natl. Rural Health Care Assoc. 2010, 26, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canevelli, M.; Bruno, G.; Cesari, M. Providing Simultaneous COVID-19-sensitive and Dementia-Sensitive Careas We Transition from Crisis Careto Ongoing Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 968–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, Y.S.; Kim, J.K.; Hur, J.; Chang, M.C. How about actively using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossen, A.L.; Kim, H.; Williams, K.N.; Steinhoff, A.E.; Strieker, M. Emerging roles for telemedicine and smart technologies in dementia care. Smart Homecare Technol. Telehealth 2015, 3, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.; Fawcett, J. The concepts of health in equality, disparities and equityin the era of population health. Appl. Nurs. Res. ANR 2020, 56, 151367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerpershoek, L.; de Vugt, M.; Wolfs, C.; Orrell, M.; Woods, B.; Jelley, H.; Meyer, G.; Bieber, A.; Stephan, A.; Selbaek, G.; et al. Is the reequity in initial access to formal dementia care in Europe? The Andersen Model applied to the Actif care cohort. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 35, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, C.; Morris, R.; Rothlind, J.; Yaffe, K. Video-Telemedicine in a memory disorders clinic: Evaluation and management of rural elders with cognitive impairment. Telemed. J. E-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2011, 17, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillie, M.; Ali, D.; Vadlamuri, D.; Carstarphen, K.J. Telehealth Literacy as a Social Determinant of Health: A Novel Screening Toolto Support Vulnerable Patient Equity. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2022, 6, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposo, V.L. Telemedicine: The legal framework (orthelackofit) in Europe. GMS Health Technol. Assess. 2016, 12, Doc03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caetano, R.; Silva, A.B.; Guedes, A.; Paiva, C.C.N.; Ribeiro, G.D.R.; Santos, D.L.; Silva, R.M.D. Challenges and opportunities for telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: Ideas on spaces and initiatives in the Brazilian context. Cad. Saude Publica 2020, 36, e00088920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindarajan, R.; Anderson, E.R.; Hesselbrock, R.R.; Madhavan, R.; Moo, L.R.; Mowzoon, N.; Otis, J.; Rubin, M.N.; Soni, M.; Tsao, J.W.; et al. Developing an outline for teleneurology curriculum: AAN Telemedicine Work Group recommendations. Neurology 2017, 89, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.B.; Nelson, V.R.; Holtz, B.E. Barriers for Telemedicine Use Among Nonusersatthe Beginning of the Pandemic. Telemed. Rep. 2021, 2, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.; Newton, L.; Pritchard, G.; Finch, T.; Brittain, K.; Robinson, L. The provision of assistive technology products and services for people with Dementiain the United Kingdom. Dementia 2016, 15, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A.; Cotten, S.R.; Xie, B. A Double Burden of Exclusion? Digital and Social Exclusion of Older Adults in Times of COVID-19. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e99–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ScottKruse, C.; Karem, P.; Shifflett, K.; Vegi, L.; Ravi, K.; Brooks, M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine world wide: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, K.; Lu, A.D.; Shi, Y.; Covinsky, K.E. Assessing Telemedicine Unreadinessamong Older Adults in the United States during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gately, M.E.; Tickle-Degnen, L.; McLaren, J.E.; Ward, N.; Ladin, K.; Moo, L.R. Factors Influencing Barriers and Facilitators to In-home Video Telehealth for Dementia Management. Clin. Gerontol. 2022, 45, 1020–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitzner, T.L.; Savla, J.; Boot, W.R.; Sharit, J.; Charness, N.; Czaja, S.J.; Rogers, W.A. Technology Adoptionby Older Adults: Findings from the PRISM Trial. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eruchalu, C.N.; Pichardo, M.S.; Bharadwaj, M.; Rodriguez, C.B.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Bergmark, R.W.; Bates, D.W.; Ortega, G. The Expanding Digital Divide: Digital Health Access Inequities during the COVID-19 Pandemic in New York City. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2021, 98, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arighi, A.; Fumagalli, G.G.; Carandini, T.; Pietroboni, A.M.; DeRiz, M.A.; Galimberti, D.; Scarpini, E. Facing the digital divide into a dementia clinic during COVID-19 pandemic: Caregiver age matters. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 42, 1247–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.; Peri, K. Challenges to dementia care during COVID-19: Innovations in remote delivery of group Cognitive Stimulation Therapy. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.K.; Yan, S.H.; Lin, I.C.; Tsai, M.T.; Chen, C.C.; Woung, L.C. Apilotstudy of the telecare medical support system as an intervention in dementia care: The views and experiences of primary caregivers. J. Nurs. Res. JNR 2012, 20, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, M.; Ljunggren, B.; Lindqvist, R.; Carlsson, M. Staff perceptions of job satisfaction and life situation before and 6 and 12 months after increase dinformation technology support in dementia care. J. Telemed. Telecare 2005, 11, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunting, G.; Shahid, N.; Sahakyan, Y.; Fan, I.; Moneypenny, C.R.; Stanimirovic, A.; North, T.; Petrosyan, Y.; Krahn, M.D.; Rac, V.E. Amulti-level qualitative analysis of Telehomecarein Ontario: Challenges ando pportunities. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhon, H.; Sekhon, K.; Launay, C.; Afililo, M.; Innocente, N.; Vahia, I.; Rej, S.; Beauchet, O. Telemedicine and the rural dementia population: A systematic review. Maturitas 2021, 143, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgeton, E.; Aubert, L.; Pierrard, N.; Gaborieau, G.; Berrut, G.; de Decker, L. General practitioners adherence to recommendations from geriatric assessments made during teleconsultations for the elderly living in nursing homes. Maturitas 2015, 82, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ftouni, R.; AlJardali, B.; Hamdanieh, M.; Ftouni, L.; Salem, N. Challenges of Telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalicki, A.V.; Moody, K.A.; Franzosa, E.; Gliatto, P.M.; Ornstein, K.A. Barriers to telehealth access among homebound older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Health Care Quality Dimension | Definition | Examples of the Importance of High Quality of Care in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | The provision of evidence-based health services to individuals who need them | Lack of education and training of primary care physicians in the diagnosis and treatment of dementia | [4,34] |

| The differential diagnosis of dementia causes has important clinical impact | [35] | ||

| The differential diagnosis between dementia mimics has important clinical impact | [36] | ||

| Identification of atypical clinical presentations and rarer forms of dementia, especially at younger agesis challenging | [36] | ||

| Detailed neuropsychological testing is often required for the accurate dementia diagnosis, especially at early stages | [37] | ||

| The limited time of primary care physicians does not allow sufficient discussion, counseling, and personalized management plan | [34] | ||

| Adherence to dementia guidelines and evidence-based recommendations is associated with better overall quality of care | [38] | ||

| Adherence of primary care physicians to dementia guidelines and quality care indicators is inadequate | [38,39,40] | ||

| Most patients with dementia have inadequate access to appropriate formal care services | [41] | ||

| The participation of physicians in educational seminars on dementia care is associated with improved quality of life | [38] | ||

| Safety | The avoidance of harmto people for whom the care is intended. | Traveling to specialized physicians is challenging for dementia patients due to their cognitive and mobility issues | [7] |

| COVID-19 poses high infection risks in traditional in-person clinical settings in the elderly | [33] | ||

| During the COVID-19 pandemic, many older patients with dementia do not receive appropriate medical care | [42] | ||

| Inappropriate and high prescription of antipsychotic drugs for patients with dementia is high | [43,44] | ||

| Improper use of antipsychotics is associated with a higher risk of death and ischemic events in the elderly | [45] | ||

| AD diagnosis is associated with higher COVID-19-associated mortality | [46] | ||

| People-centeredness | The delivery of care that respects and responds to personal needs, values, and preferences | Individualized interventions by primary care physicians in collaboration with dementia care managers are associated with lower caregiver stress and behavioral symptoms | [6,47,48] |

| Personalized evaluation and management are associated with higher-quality dementia care | [34] | ||

| Care models with shared decision making is associated with improved satisfaction | [49] | ||

| Patients’ and family members’ preferences, perceptions, and needs are an integral part of dementia care | [49] | ||

| Timeliness | The reduction of waiting times and delays that could be harmful not only for those who receive but also give care | Diagnostic sensitivity of dementia is correlated with the frequency of contact between patients and providers | [4] |

| Regular monitoring contributes to a better quality of life | [38,43] | ||

| Specialized neurologists and memory clinics are lacking in remote areas | [50] | ||

| Earlier detection of cognitive decline is associated with better health outcomes | [49] | ||

| AD prevalence is higher in rural areas | [51] | ||

| Equitability | The provision of care that is independent of age, race, ethnicity, geographical location, socioeconomic status, sex, gender, religion, political or linguistic affiliation | Limited recruitment of physicians at rural health centers | [22] |

| Lack of transportation infrastructure and socioeconomic disparities limit the accessibility of patients living in rural areas | [52] | ||

| Often long travel distances for appropriate access to specialized care | [53] | ||

| Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, a greater percentage of non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics had a missed or delayed dementia diagnosis | [54] | ||

| Integrated care | Coordinated care across different levels and providers, allowing the availability of all appropriate health services throughout life course | Patients, caregivers, and family members often require referral for legal issues, advice on long-term facilities, improvement of home environment, psychological support, information about available services, support groups, educational resources, and administrative assistance | [34] |

| Cooperation between different healthcare professionals for dementia care is limited, and community-based organizations are currently underutilized and inadequately incorporated into the healthcare system | [34,43] | ||

| Social worker engagement improves the quality of care for dementia | [38] | ||

| Transdisciplinary collaborative team care (physicians, neuropsychologists, social workers, registered nurses, and nurse practitioner managers) and linkages to appropriate community resources are associated with better quality of care, improved counseling, reduced caregivers’ stress and patients’ behavioral and depressive symptoms, and fewer hospitalizations and visits to the emergency departments | [38,55,56] | ||

| In integrated care, team members contribute with their expertise and clinical or management strengths for appropriate dementia care | [49] | ||

| Fragmented care and difficult-to-navigate healthcare services are significant barriers to treatment | [57] | ||

| The integration of community-based organizations (e.g., Alzheimer’s Association) into the health systems improves quality of care for patients with dementia | [55] | ||

| Participation of nurse practitioners in care is associated with higher healthcare quality for dementia patients, reduced risk of falls and incontinence, and better adherence to care recommendations | [58,59] | ||

| Efficiency | Maximizing the benefit of available care resources and avoiding relevant waste | Fewer emergency department visits and unnecessary hospitalizations may be associated with lower public healthcare costs | [22] |

| Changes in routine and home environment may cause anxiety and exacerbate behavior symptoms in dementia patients | [60] | ||

| Dementia care creates significant economic burden for patients, families, caregivers, and healthcare systems | [61] |

| Health Care Quality Dimension | The Role of Telemedicine in Each of the Quality of Care Dimensions in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Related Dementias | References |

|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | Telemedicine is effective in confirming or providing a diagnosis for cognitive impairment | [27,62] |

| Alterations in drug prescriptions were recommended via telemedicine in more than 1/3 of patients (longitudianl study, 3-year follow-up period, 45 clinical video telehealth encounters) | [62] | |

| Rural community clinics can be effectively connected through teleconsultations with physicians specialized in dementia care in University Hospitals (longitudinal study, 188 patients with dementia, face-to-face versus telemedicine care) | [63] | |

| Telephone-based remote care is feasible for younger patients with dementia (retrospective study for a 2-year period, 1121 calls) | [64] | |

| Telemedicine provided by specialists is associated with 1.8 and 1.1 medication alterations for patients with dementia at initial assessments and follow-up visits, respectively, for 12-month period (longitudinal study, 199 clinical video telehealth patient encounters) | [65] | |

| Teleconsultation in dementia is associated with treatment modifications at approximately 10%, especially for those with AD or living with a relative (multicenter study, 874 patients) | [66] | |

| Telemedicine use is associated with longer treatment duration and compliance in dementia patients during a 5-year period (259 patients in-person, 168 patients via telemedicine) | [67] | |

| Telemedicine is feasible for follow-up and ongoing care | [50,68] | |

| Fewer canceled medical visits and improved transitions between the follow-up clinic and primary care supported by a case manager or geriatric assessor via telemedicine (55 telemedicine sessions) | [68] | |

| Telemedicine via video-conferencing are associated with improved quality of life, better physical and mental health, less perceived burden, and higher self-efficacy, compared to only telephone-based visits among patients with neurodegenerative diseases | [42,69] | |

| Telemedicine via video-conferencing may improve the well-being and resilience of patients (self-efficacy, perceived burden) with neurocognitive disorders and caregivers and avert MoCA deterioration (60 older adults with neurocognitive disorder; supplementary telehealth via video conference vs. via telephone) | [60] | |

| Telemedicine is a valid triage tool for patients with frontotemporal dementia regarding clinical worsening (CDR-FTD scale), change in quality of life, and COVID-19 symptoms, with high satisfaction of the caregivers(26 telemedicine clinical interviews with caregivers, 4 with both patients and caregivers | [70] | |

| Telemedicine for acute illnesses is associated with less unnecessary visits to emergency departments among older adults with dementia in senior living communities (1 year of access to telemedicine is associated with a 24% reduction in emergency department visits) | [71] | |

| Emergency department use was reduced for ambulatory-care sensitive conditions after the introduction of telemedicine for older individuals in senior living communities (prospective cohort study at a primary care geriatrics practice) | [72] | |

| Videoconferenced geriatric medicine grand rounds on a weekly basis are feasible and beneficial for healthcare professionals in 9 urban and 14 remote rural areas (questionnaire: reason of attendance, evaluations of presentations) | [73] | |

| Safety | Specialists could identify inappropriate drug use that might contribute to cognitive decline in almost half of the visits through telemedicine (interprofessional dementia assessment by a geriatrician, geropsychologist, geriatric psychiatrist or neurologist, and social worker using clinical videotelehealth technology) | [74] |

| Telemedicine through video-conferencing is associated with better quality of life for patients with dementia compared to only telephone-based visits during the social isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic (60 older adults with neurocognitive disorder; supplementary telehealth via video-conference vs. via telephone) | [60] | |

| In case of home-based video-conferencing, telemedicine allows the physician to directly observe the home environment of the patient and suggest alterations such as individualized recommendations for the prevention of falls (feasibility study, 10 videoconferencing visits) | [75] | |

| People-centeredness | Patients and caregivers accept telemedicine as a very convenient model of care. Patients with AD and their caregivers are very satisfied with telemedicine (overall satisfaction rates 88–98%) | [62,76,77,78] |

| Telemedicine is preferred over in-person visits | [76,79] | |

| Similar satisfaction rates are observed between telemedicine and traditional in-person visits (230 participants recruited from outpatient dementia clinic) | [80] | |

| Telemedicine allows for the identification of caregivers’ needs (rural caregiving telemedicine program, 1-year questionnaire on risk factors, behavioral management, diagnosis, and medications) | [81] | |

| Semi-structured interviews for the experiences of patients and caregivers on telemedicine demonstrated that although proactive teleconsultations during the COVID-19 pandemic are effective, they should be focused on needs and practical recommendations (community-based patients living with dementia (30) and their carers (31)) | [82] | |

| Telemedicine allows family members living away from the patient’s home to attend the video-conference visit, allowing for shared decision making (older participants, 72.1% with cognitive impairment, 32 patient evaluations, 80 clinician feedback evaluations, satisfaction, care access during pandemic, and travel and time savings) | [83] | |

| Assistive technology use and telecare for individuals with dementia are not associated with prolonged time of independent living (randomized controlled trial, 495 participants) | [84] | |

| Timeliness | Telemedicine allows for real-time medical reporting and sharing, thereby avoiding unnecessary delays (videoconferencing 28 patients from outpatient clinic) | [24] |

| The use of wearable devices, remote monitoring sensors, or web-based platforms may facilitate early detection of medical emergencies and timely intervention | [33,85] | |

| Telemedicine reduces waiting times for appointments with specialized physicians, allowing earlier diagnosis and treatment of dementia-related various medical complaints(60 older adults with neurocognitive disorder; supplementary telehealth via video conference vs. via telephone) | [60] | |

| Equitability | Telemedicine in rural areas is effective, with high satisfaction rates, allowing for better access to timely care, reduced cost, and avoidance of unnecessary transportation | [22,86,87] |

| Telemedicine facilitates the elimination of geographical disparities, allowing patients with dementia from rural and urban areas to access specialized healthcare | [53,88] | |

| Digital literacy, lower education level, and worse cognitive function are associated with less engagement in remote interventions promoting lifestyle modifications among older adults | [89,90] | |

| Integrated care | In a Tennessee-based program, specialists recommended referrals to social workers and the use of long-term care services in almost two-thirds of the telemedicine visits | [62,76] |

| A Pittsburgh-based telemedicine program for dementia care, including a geriatrician, geriatric psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, and nurse manager, is highly acceptable and successful fur rural areas (patient satisfaction survey, 156 clinic visits) | [74] | |

| Telemedicine may significantly enable interdisciplinary dementia care | [86,87,91,92,93] | |

| The use of a nurse practitioner-led mobile memory clinic incorporated in the general practice targeting patients with poor socioeconomic status and limited access to care is feasible and acceptable (1-year, 102 patients) | [94] | |

| Telemedicine can aid in the assessment and management of psychotic symptoms of patients with neurodegenerative disorders in long-term care facilities (multidisciplinary consensus panelist of best practices in telemedicine for patients with dementia-related psychosis or Parkinson’s disease-related psychosis) | [95] | |

| Telemedicine allows telerehabilitation for patients with AD dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and mild cognitive impairment | [96,97,98,99] | |

| Computerized cognitive training among patients with or at risk for dementia is effective | [100,101,102] | |

| Speech therapy is effective in primary progressive aphasia and alexia | [103,104] | |

| Virtual reality for patients with dementia is associated with reduced neuropsychiatric symptoms (i.e., depression and agitation, apathy) and quality of life | [105,106,107] | |

| Tele-exercise programs through video conferencing are feasible and acceptable among patients with AD and their caregivers | [108,109] | |

| Video-based caregiver support for stress, education, and training for behavioral symptoms are feasible and effective | [110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127] | |

| Remote telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapy to caregivers of patients with AD for the enhancement of physical or mental health is effective (273 family caregivers, 50-min sessions) | [128] | |

| Remote cognitive behavioral therapy to caregivers of patients with AD for insomnia treatment is also effective (four-session CBT-I protocol) | [129] | |

| Most caregivers are satisfied with the FamTechCare service, which allows for tailored expert feedback based on video recordings (multisite randomized controlled trial, satisfaction survey) | [130] | |

| Subjective burden levels of the caregivers have not been significantly affected by a telehealth-based intervention, while objective measures of activity and sleep showed a slight decline | [131] | |

| Assistive technology and telecare are not associated with reduced caregivers’ burden (randomized-controlled trial) | [132] | |

| Efficiency | Telemedicine reduces traveled distance and time spent traveling compared to in-person visits | [62,74,80] |

| Telemedicine is beneficial for patients in advanced stages of dementia with mobility limitations, being bedridden or in a wheelchair, whose transportation is costly and time-consuming | [52,78] | |

| The avoidance of unnecessary transportations and the distance and time saved have significant effects on patients, caregivers, and family members that need to accompany them for medical visits(older participants, 72.1% with cognitive impairment, 32 patient evaluations, 80 clinician feedback evaluations, satisfaction, care access during pandemic, and travel and time savings) | [83] | |

| During the COVID-19 pandemic, e-mail-based care for patients with dementia is feasible and effective (retrospective analysis, 14-month period, 374 e-mails sent by 213 patients) | [133] | |

| Videoconferencing is cost-effective for dementia diagnosis, in case the specialist should drive for more than two hours in order to deliver in-person service (break-even analysis) | [134] | |

| The FamTechCare intervention aiming to provide dementia specialists feedback to caregivers based on video recordings is cost-effective, compared to telephone support interventions (clinical trial, cost-effectiveness analysis) | [135] | |

| A remote caregiver support intervention only resulted in short-term cost savings, which could not be maintained for one year (randomized controlled trial) | [136] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Angelopoulou, E.; Papachristou, N.; Bougea, A.; Stanitsa, E.; Kontaxopoulou, D.; Fragkiadaki, S.; Pavlou, D.; Koros, C.; Değirmenci, Y.; Papatriantafyllou, J.; et al. How Telemedicine Can Improve the Quality of Care for Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias? A Narrative Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58121705

Angelopoulou E, Papachristou N, Bougea A, Stanitsa E, Kontaxopoulou D, Fragkiadaki S, Pavlou D, Koros C, Değirmenci Y, Papatriantafyllou J, et al. How Telemedicine Can Improve the Quality of Care for Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias? A Narrative Review. Medicina. 2022; 58(12):1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58121705

Chicago/Turabian StyleAngelopoulou, Efthalia, Nikolaos Papachristou, Anastasia Bougea, Evangelia Stanitsa, Dionysia Kontaxopoulou, Stella Fragkiadaki, Dimosthenis Pavlou, Christos Koros, Yıldız Değirmenci, John Papatriantafyllou, and et al. 2022. "How Telemedicine Can Improve the Quality of Care for Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias? A Narrative Review" Medicina 58, no. 12: 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58121705

APA StyleAngelopoulou, E., Papachristou, N., Bougea, A., Stanitsa, E., Kontaxopoulou, D., Fragkiadaki, S., Pavlou, D., Koros, C., Değirmenci, Y., Papatriantafyllou, J., Thireos, E., Politis, A., Tsouros, A., Bamidis, P., Stefanis, L., & Papageorgiou, S. (2022). How Telemedicine Can Improve the Quality of Care for Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias? A Narrative Review. Medicina, 58(12), 1705. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58121705