Malignant Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast and Pregnancy: A Rare Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

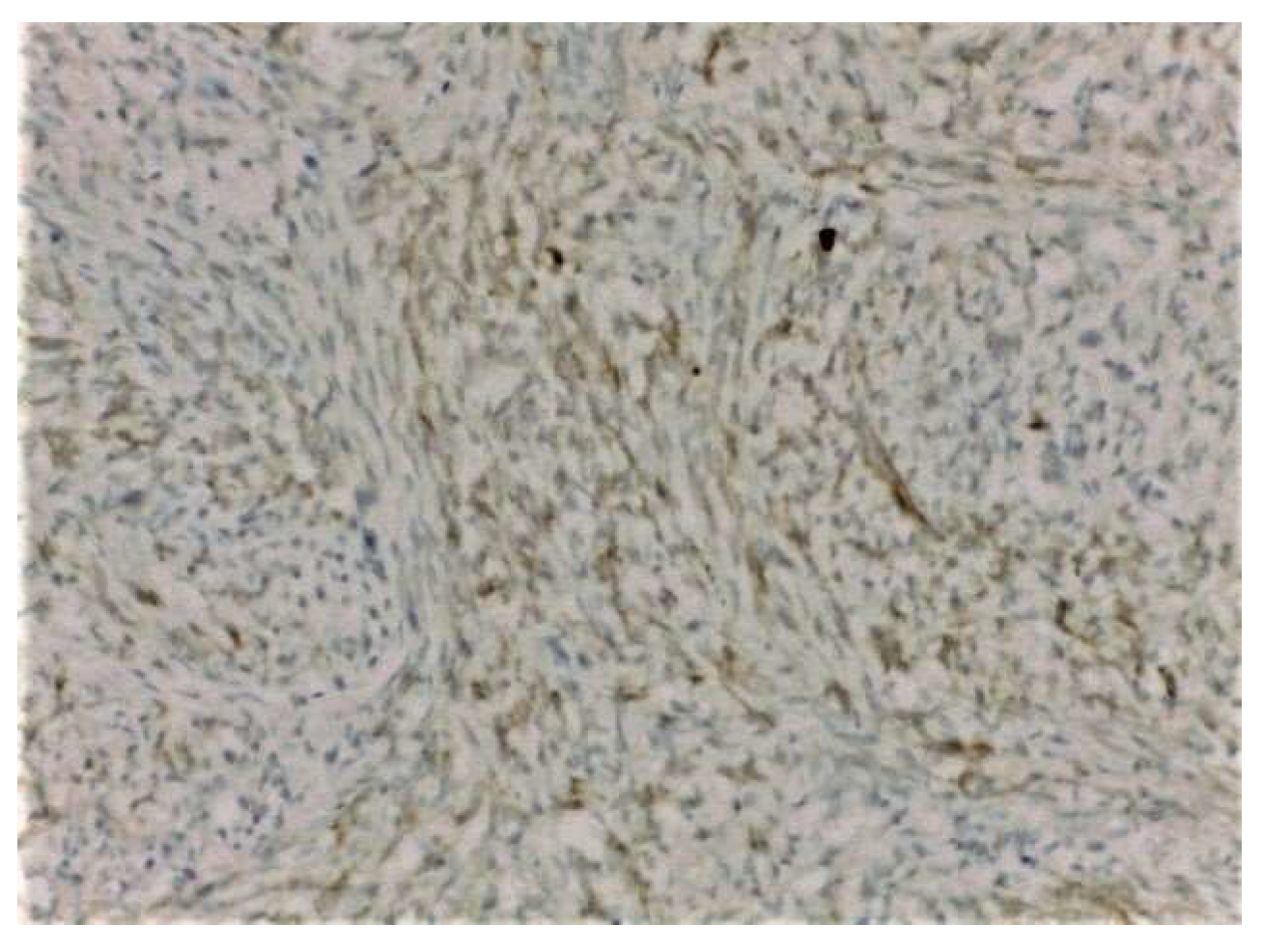

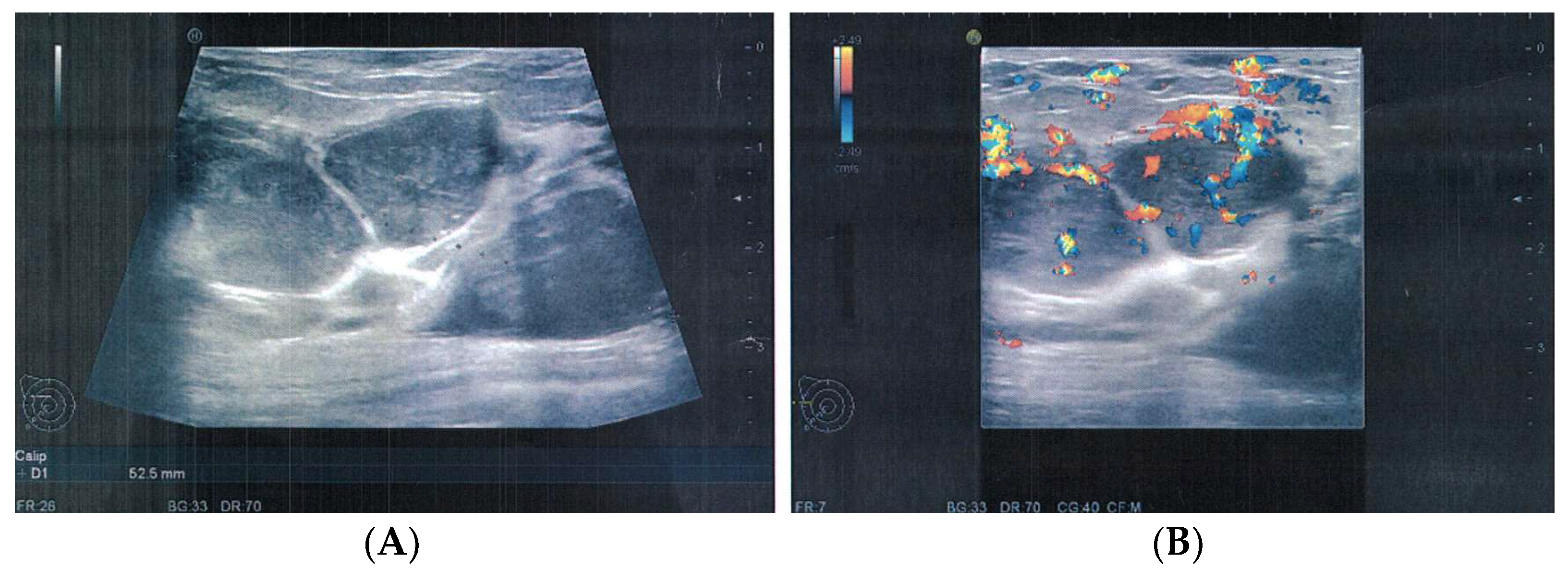

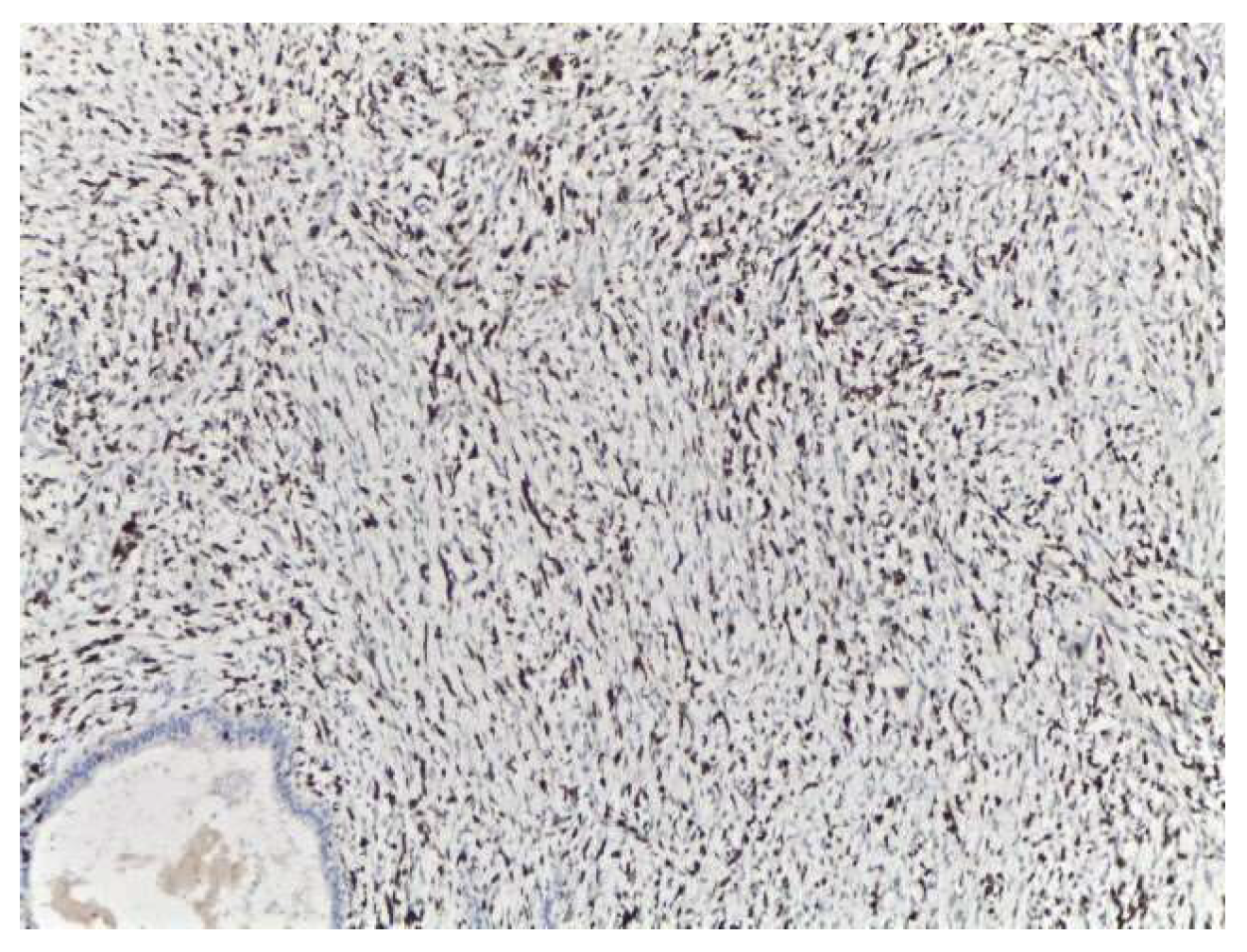

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaney, A.W.; Pollack, A.; McNeese, M.D.; Zagars, G.K.; Pisters, P.W.T.; Pollock, R.E.; Hunt, K.K. Primary treatment of cystosarcoma phyllodes of the breast. Cancer 2000, 89, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, K.; Allison, K.H.; Kim, J.N.; Rahbar, H.; Anderson, B.O. Phyllodes tumors. In Diseases of the Breast; Harris, J., Lippman, M.E., Morrow, M., Osborne, K.C., Eds.; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elston, C.W.; Ellis, I.O. The Breast. Systemic Pathology, 3rd ed.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 2000; Volume 13, pp. 147–186. [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli, F.A.; Devilee, P. Pathology and genetics of tumors of the breast and female genital organs. In World Health Organization Classification of Tumors; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2003; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, L.; Deapen, D.; Ross, R.K. The descriptive epidemiology of malignant cystosarcoma phyllodes tumors of the breast. Cancer 1993, 71, 3020–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, A.M.; Chakravarthy, A.B.; Chugh, R. Phyllodes Tumors of the Breast. June 2020. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Norris, H.J.; Taylor, H.B. Relationship of histologic features to behavior of cystosarcoma phyllodes. Analysis of ninety-four cases. Cancer 1967, 20, 2090–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, A.V.; Clark, B.D.; Goldberg, J.; Hoque, L.W.; Bernik, S.F.; Flynn, L.W.; Susnik, B.; Giri, D.; Polo, K.; Patil, S.; et al. Clinicopathologic Features and Long-Term Outcomes of 293 Phyllodes Tumors of the Breast. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 14, 2961–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, J.M.; Alston, R.D.; McNally, R.; Evans, G.; Kelsey, A.M.; Harris, M.; Eden, O.B.; Varley, J.M. Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in carriers of germline TP53 mutations. Oncogene 2001, 20, 4621–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telli, M.L.; Horst, K.C.; Guardino, A.E.; Dirbas, F.M.; Carlson, R.W. Phyllodes Tumors of the Breast: Natural History, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2007, 5, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinfuss, M.; Mituś, J.; Duda, K.; Stelmach, A.; Ryś, J.; Smolak, K. The treatment and prognosis of patients with phyllodes tumor of the breast: An analysis of 170 cases. Cancer 1996, 77, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuuchi, H.; Soeda, H.; Matsuo, Y.; Okafuji, T.; Eguchi, T.; Sakai, S.; Kuroki, S.; Tokunaga, E.; Ohno, S.; Nishiyama, K.; et al. Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast: Correlation between MR Findings and Histologic Grade. Radiology 2006, 241, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farria, D.M.; Gorczyca, D.P.; Barsky, S.H.; Sinha, S.; Bassett, L.W. Benign phyllodes tumor of the breast: MR imaging features. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1996, 167, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Kleer, C.G. Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast: Histopathologic Features, Differential Diagnosis, and Molecular/Genetic Updates. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, O.K.; Lee, C.M.; Tward, J.D.; Chappel, C.D.; Gaffney, D.K. Malignant phyllodes tumor of the female breast: Association of primary therapy with cause-specific survival from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Cancer 2006, 107, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnerlich, J.L.; Williams, R.T.; Yao, K.; Jaskowiak, N.; Kulkarni, S.A. Utilization of Radiotherapy for Malignant Phyllodes Tumors: Analysis of the National Cancer Data Base, 1998–2009. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Ren, G. Effects of adjuvant radiotherapy on borderline and malignant phyllodes tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 3, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Vasquez, F.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Broglio, K.; López-Basave, H.N.; Gallardo, D.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; De La Garza, J.G. Adjuvant Chemotherapy with Doxorubicin and Dacarbazine has No Effect in Recurrence-Free Survival of Malignant Phyllodes Tumors of the Breast. Breast J. 2007, 13, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkes, A.; Wang, W.-L.; Patel, S.; Leung, C.H.; Lin, H.; Conley, A.P.; Somaiah, N.; Araujo, D.M.; Zarzour, M.; Livingston, J.A.; et al. Outcomes of systemic therapy in metastatic phyllodes tumor of the breast. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 186, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mituś, J.W.; Blecharz, P.; Walasek, T.; Reinfuss, M.; Jakubowicz, J.; Kulpa, J. Treatment of Patients with Distant Metastases from Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast. World J. Surg. 2016, 40, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipour, S.; Eskandari, A.; Johar, F.M.; Furuya, S. Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast during Pregnancy and Lactation; A Systematic Review. Arch. Iran. Med. 2020, 23, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narla, S.L.; Stephen, P.; Kurian, A.; Annapurneswari, S. Well-differentiated liposarcoma of the breast arising in a background of malignant Phyllodes tumor in a pregnant woman: A rare case report and review of literature. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2018, 61, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaker, K.M.; Sahoo, S.; Schweichler, M.R.; Chagpar, A.B. Malignant phyllodes tumor in pregnancy. Am. Surg. 2010, 76, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelten, C.; Boyaci, C.; Leblebici, C.; Behzatoglu, K.; Trabulus, D.C.; Sari, S.; Nazli, M.A.; Bozkurt, E.R. Malignant Phyllodes Tumor Including Aneurysmal Bone Cyst-Like Areas in Pregnancy—A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Breast Care 2016, 11, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, L.F.; Gaillard, W.F.; Wallace, J.-A.; Spiguel, L.R.P.; Alizadeh, L.; Lentz, A.; Shaw, C. A Case of a Giant Borderline Phyllodes Tumor Early in Pregnancy Treated with Mastectomy and Immediate Breast Reconstruction. Breast J. 2016, 22, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.-X.; Kong, X.-Y.; Zhai, J.; Fang, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, J. Fatal outcome of malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast in pregnancy: A case and literature review. Gland. Surg. 2021, 10, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testori, A.; Meroni, S.; Errico, V.; Travaglini, R.; Voulaz, E.; Alloisio, M. Huge malignant phyllodes breast tumor: A real entity in a new era of early breast cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tortoriello, M.G.; Cerra, R.; Di Bonito, M.; Botti, G.; Cordaro, F.G.; Caputo, E.; Tortoriello, R. A Giant Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast: A Case Report in Pregnancy. Ann. Clin. Case Rep. 2017, 2, 1311. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustață, L.; Gică, N.; Botezatu, R.; Chirculescu, R.; Gică, C.; Peltecu, G.; Panaitescu, A.M. Malignant Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast and Pregnancy: A Rare Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58010036

Mustață L, Gică N, Botezatu R, Chirculescu R, Gică C, Peltecu G, Panaitescu AM. Malignant Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast and Pregnancy: A Rare Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina. 2022; 58(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustață, Laura, Nicolae Gică, Radu Botezatu, Raluca Chirculescu, Corina Gică, Gheorghe Peltecu, and Anca Maria Panaitescu. 2022. "Malignant Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast and Pregnancy: A Rare Case Report and Literature Review" Medicina 58, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58010036

APA StyleMustață, L., Gică, N., Botezatu, R., Chirculescu, R., Gică, C., Peltecu, G., & Panaitescu, A. M. (2022). Malignant Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast and Pregnancy: A Rare Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina, 58(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58010036