Primary Non-Hodgkin Uterine Lymphoma of the Cervix: A Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods and Results

3. Discussions and Literature Review

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NCCN. Guidelines for B-cell Lymphomas V2.2018. Available online: https://oncolife.com.ua/doc/nccn/B-Cell_Lymphomas.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Hilal, Z.; Hartmann, F.; Dogan, A.; Cetin, C.; Krentel, H.; Schiermeier, S.; Schultheis, B.; Tempfer, C.B. Lymphoma of the Cervix: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 4931–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mandato, V.D.; Palermo, R.; Falbo, A.; Capodanno, I.; Capodanno, F.; Gelli, M.C.; Aguzzoli, L.; Abrate, M.; La Sala, G.B. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the uterus: Case report and review. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 4377–4390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Jing, X.; Liu, B.; Meng, X.; Sun, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Fu, Z. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the vagina: A case report. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3504–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Contreras-Chavez, P.; Aliaga, R.; Samee, M.; Anampa-Guzmán, A. Primary Vaginal Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cureus 2018, 10, e3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nasioudis, D.; Kampaktsis, P.N.; Frey, M.; Witkin, S.S.; Holcomb, K. Primary lymphoma of the female genital tract: An analysis of 697 cases. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 145, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, D.R.; Carducci, M.A.; Compton, C.C.; Fritz, A.G.; Greene, F. Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 607–611. [Google Scholar]

- Del, M.; Angeles, M.A.; Syrykh, C.; Martínez-Gómez, C.; Martínez, A.; Ferron, G.; Gabiache, E.; Oberic, L. Primary B-Cell lymphoma of the uterine cervix presenting with right ureter hydronephrosis: A case report. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 34, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, D.M.; Patel, P.; Guzman, G.; Ni, H. A Case of Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma Involving the Uterine Cervix Presenting As Vaginal Spotting. Cureus 2020, 12, e8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goda, J.S.; Gaikwad, U.; Narayan, A.; Kurkure, D.; Yadav, S.; Khanna, N.; Jain, H.; Bagal, B.; Epari, S.; Singh, P.; et al. Primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma of Uterine Cervix: Treatment outcomes of a rare entity with literature review. Cancer Rep. 2020, 3, e1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, C.S.; Filho, E.; Domit, I.L.; Ching, L.I. Three Unexpected Cases of Gynecological B-Cell Lymphoma—EP711. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, A403. [Google Scholar]

- Seidler, S.J.; Lovey, P.Y.; Busuioc, C.I.; Huber, D.E. Gynaecological Lymphomas: Case Reports and Literature Review of Primary Extranodal Female Genital Tract and Breast Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas. Arch. Cancer Res. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubo, A.M.; Soto, Z.M.; Cruz, M.; Doyague, M.J.; Sancho, V.; Fraino, A.; Blanco, O.; Puig, N.; Alcoceba, M.; González, M.; et al. Primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the uterine cervix successfully treated by combined chemotherapy alone. Medicine 2017, 96, e6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSana, B.; Mussetto, A.B.; Macera, A.; Mariani, L.; De Rosa, G.; Cirillo, S. Rare case of uterine cervix lymphoma with spontaneous regression: Case report. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 47, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Deisch, J.; Tavares, M.; Haixia, Q.; Cobb, C.; Raza, A.S. Primary B-cell lymphoma of the uterine cervix: Presentation in Pap-test slide and cervical biopsy. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2016, 45, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalo, A.; Caseiro, L.; Pereira, E.; Cortes, J. Primary lymphoma of the uterine cervix: A rare constellation of symptoms. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Díaz De-La-Noval, B.; Hernández Gutiérrez, A.; Zapardiel, I.; De-Santiago García, J.; Tejeda, D. Successful Treatment of a Primary Cervical Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma with Rituximab-CHOP Immunochemotherapy. Case Rep. Open Access Int. J. Blood Res. Disord. 2016, 3, 024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Hua, F.; Zuo, C.; Guan, Y. Primary Uterine Cervical Lymphoma Manifesting as Menolipsis Staged and Followed Up by FDG PET/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 41, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorth, J.A.; Prosnitz, L.R.; Broadwater, G.; Beaven, A.W.; Kelsey, C.R. Radio-therapy dose-response analysis for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a complete response to chemotherapy. Radiat. Oncol. 2012, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, L. Treatment outcome for primary cervix large B-cell lymphoma: A clinical analysis of thirty-seven cases. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, e17025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Article Year | No. of Cases/Patient Age (Years) | Immunohistochemistry | Histology and Pathology | Treatment | Disease-Free Time Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Contreras-Chavez P et al. [5] | 2018 | 1/79 | positive: CD20, BCL2, BCL6, CD10, MUM-1 (GC-B type), and C-MYC, Ki-67 in 70% negative: Pankeratin, Melan-A, S100, and CD3. | (DLBCL) (GC-B type), | 6 × R-CHOP | 12 months/CT |

| 2. Mathilde Del et al. [8] | 2020 | 1/36 | positive: CD45, CD20 (B-cell marker), Bcl6, Bcl2, and MYC, and negative for CD3 (T-cell marker), CD10, MUM1 (GC-B type), CD5, and cyclin D1, with a Ki67 index (60%) | (DLBCL) (GC-B type) | 6 × R-CHOP. Full response—tumour disappeared | 15 months/clinical assessment + PET-CT |

| 3. Jayant Sastri Goda et al. [10] | 2020 | 4/average age 50 (39–62) | positive: CD20, CD10, Ki-67 index 80% negative: Mum-1 (multiple myeloma oncogene 1), and Bcl-6(B-cell lymphoma-6) | (DLBCL) GC-B type (2) Non-GC-B type (2 Molecular subtype (by Hans Algorithm)) | 6 × R-CHOP + RT (45Gy) | 20 months (8–43)/clinical assessment + PET-CT/MRI |

| 4. Fontana, C S. et al. [11] | 2019 | 1/38 | − | (DLBCL) | 6 × R-CHOP + hysterectomy | 12 months/PET-CT/CT |

| 5. Seidler SJ et al. [12] | 2018 | 1/50 | positive: CD20 (B cell), CD3 (T cell), CD45, CD10, BCL-6, CD5, MUM-1(GC-B type), Cyclin D1, Ki67 negative: Bcl-2, MYC | (DLBCL) (GC-B type), | 6 × R-CHOP | 12 months/PET-CT/CT |

| 6. Cubo AM et al. [13] | 2017 | 1/51 | positive: CD20+, CD5+, BCL2+, BCL6+, CD45+, CD23+, CD43+ negative: MUM1 (GC-B type), CD10, CD30, CyclinD1, and EBER. Ki-67 and p53 positive ≥ 60% | (DLBCL) (GC-B type), | 6 × R-CHOP | 24 months/PET-CT/MRI |

| 7. Benedetta Desana et al. [14] | 2020 | 1/54 | - | (DLBCL) | 6 × R-CHOP + radical hysterectomy | 12 months/PET-CT/MRI |

| 8. Guang Yang et al. [15] | 2017 | 1/69 | positive: CD45, CD20şi PAX-5, MUM1 (GC-B type), BCL2+, BCL6+ negative: CD10 Ki67 99% | (DLBCL) (GC-B type), | 6 × R-CHOP | 12 months/PET-CT/CT |

| 9. Ana Regalo et al. [16] | 2016 | 1/40 | positive: for CD20, CD10, bcl2, and bcl6 negative: CD5, CD3, CD23, and cyclin D | (DLBCL) | 8 × R-CHOP Recidivation after 45 months + 4 × R-CHOP + RT | 45 months +3 months post-RT for recidivation/PET-CT/CT |

| 10. Díaz De-La-Noval B [17] | 2016 | 1/46 | positive: CD20, CD45, BCL6, and CD30, 50% Ki67 negative: CK-AE1/AE3, CD15, AML, CD68, BCL2, CD10, MUM1, CD5, and C-MYC | (DLBCL) (non-GC-B type) | 6 × R-CHOP | 12 months/PET-CT |

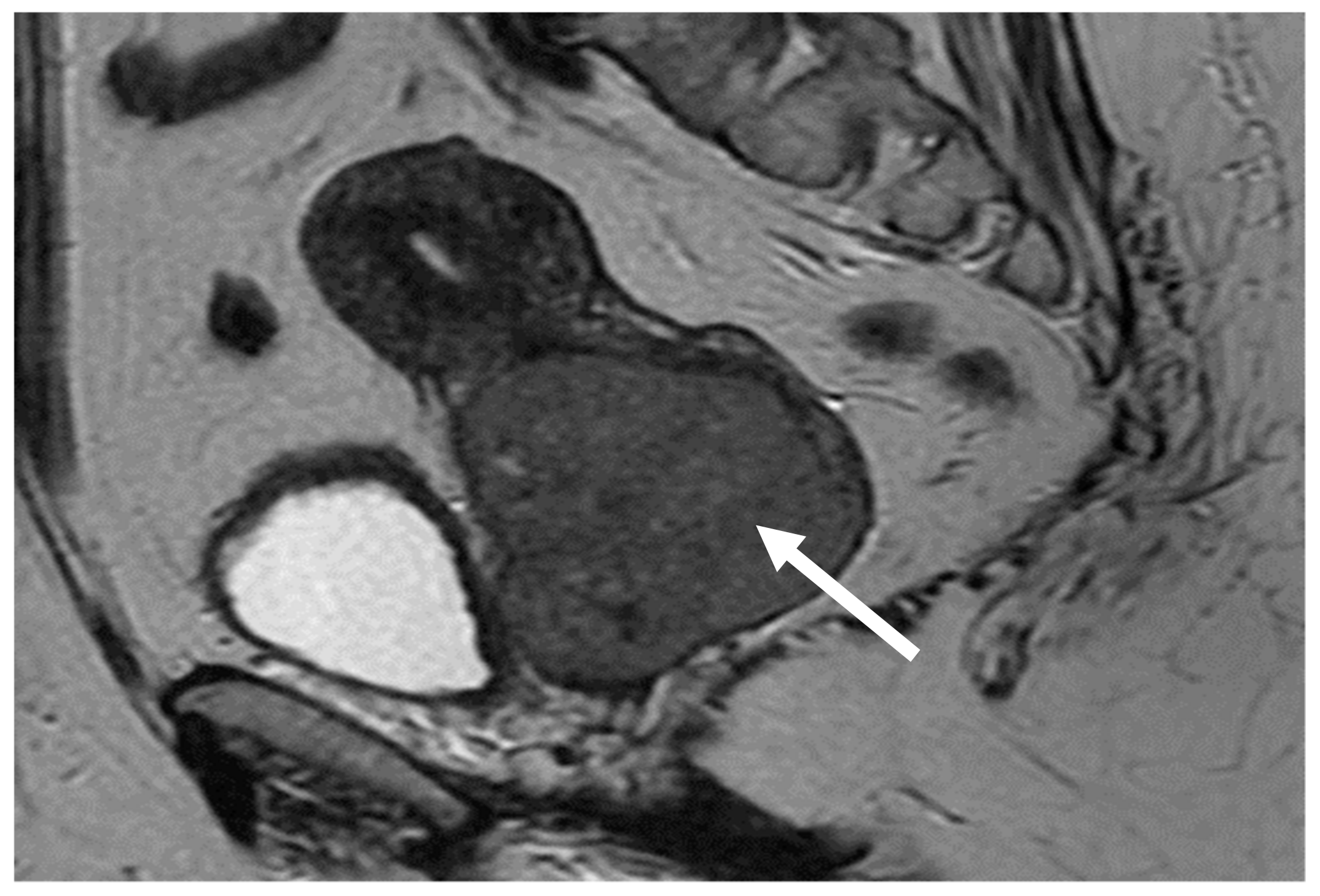

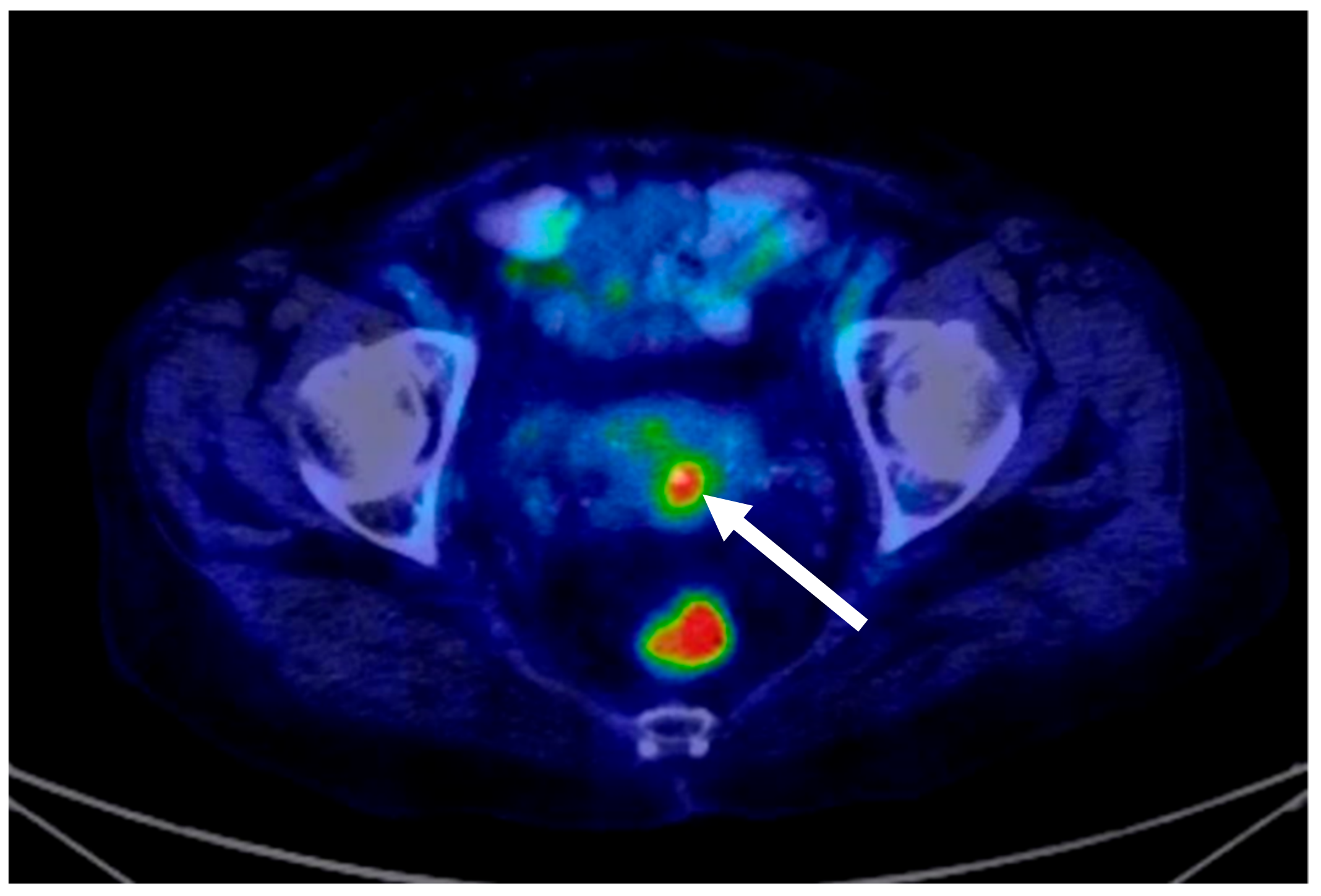

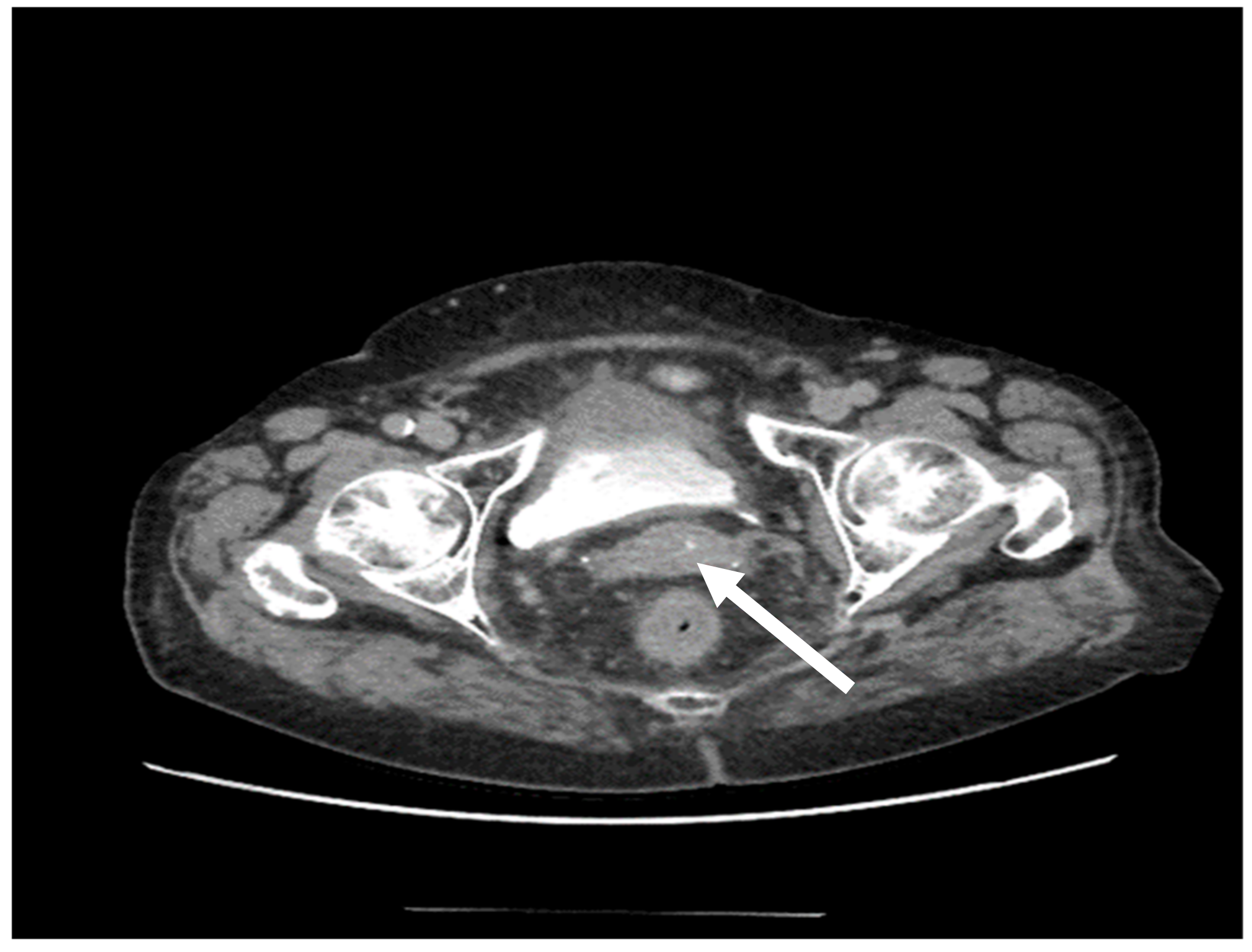

| 11. Weiyan Zhou [18] | 2016 | 1/31 | − | (DLBCL) | 6 × R-CHOP | 12 months/PET-CT/MRI |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Capsa, C.; Calustian, L.A.; Antoniu, S.A.; Bratucu, E.; Simion, L.; Prunoiu, V.-M. Primary Non-Hodgkin Uterine Lymphoma of the Cervix: A Literature Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58010106

Capsa C, Calustian LA, Antoniu SA, Bratucu E, Simion L, Prunoiu V-M. Primary Non-Hodgkin Uterine Lymphoma of the Cervix: A Literature Review. Medicina. 2022; 58(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleCapsa, Cristina, Laura Aifer Calustian, Sabina Antonela Antoniu, Eugen Bratucu, Laurentiu Simion, and Virgiliu-Mihail Prunoiu. 2022. "Primary Non-Hodgkin Uterine Lymphoma of the Cervix: A Literature Review" Medicina 58, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58010106

APA StyleCapsa, C., Calustian, L. A., Antoniu, S. A., Bratucu, E., Simion, L., & Prunoiu, V.-M. (2022). Primary Non-Hodgkin Uterine Lymphoma of the Cervix: A Literature Review. Medicina, 58(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58010106