A Systematic Review on TeleMental Health in Youth Mental Health: Focus on Anxiety, Depression and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. TeleMental Health

1.2. Telepsychiatry and/or Telepsychotherapy via Audio and/or Video Calls

1.3. Asynchronous Technology Modes

1.4. Aims of the Paper

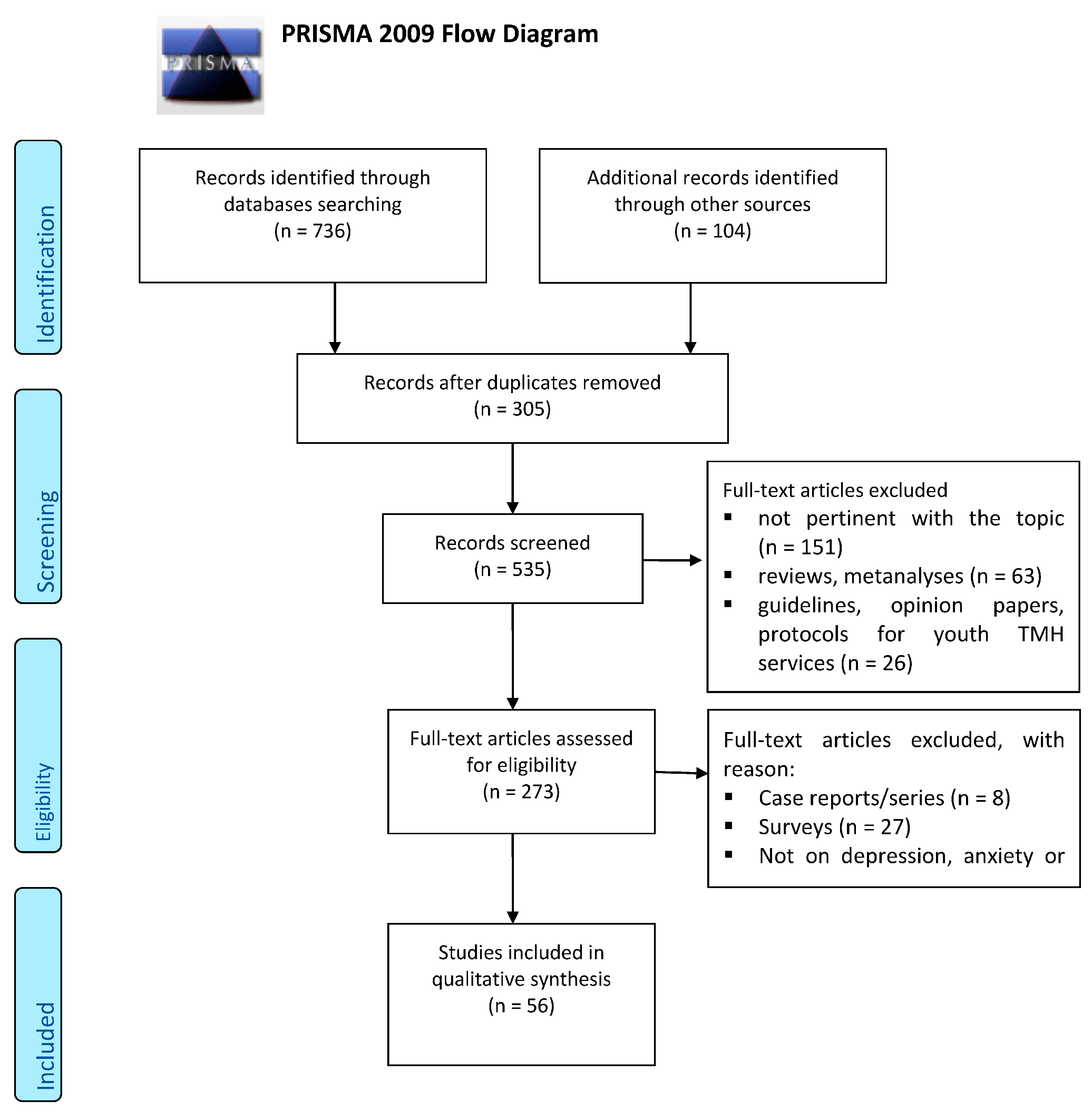

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Sources and Strategies

2.2. Study Selection, Data Extraction and Management

2.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

3. TMH in Youth Mental Health

3.1. Anxiety Disorders

3.2. Depression

3.3. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| SET | MEDLINE |

|---|---|

| 1 | Telepsychiatry |

| 2 | Telemental Health |

| 3 | Telepsychotherapy |

| 4 | Videoconferencing |

| 5 | Tele * |

| 6 | Remote |

| 7 | Sets 1–6 were combined with “OR” |

| 8 | Youth Mental Health |

| 9 | Depress * |

| 10 | Anxiety |

| 11 | Obsessive Compulsive |

| 12 | Sets 8–11 were combined with “OR” |

| 13 | Telemental health |

| 14 | Telepsychiatry |

| 15 | Adolescent Psychiatry |

| 16 | Sets 13–15 were combined with “OR” |

| 17 | Sets 7, 12 and 16 were combined with “AND” |

| 18 | Set 17 was limited to 25 January 2021 |

| Humans, no language or time restriction |

Appendix B

References

- WHO. Sixty-Fourth World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA 64.28: Youth and Health Risks. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/hac/events/wha_a64_r28_en_youth_and_health_risks.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Burns, J.M.; Davenport, T.A.; Durkin, L.A.; Luscombe, G.M.; Hickie, I.B. The internet as a setting for mental health service utilisation by young people. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, S22–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, N.; Strauss, W. The next 20 years: How customer and workforce attitudes will evolve. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shatto, B.; Erwin, K. Moving on from millennials: Preparing for generation, Z. J. Contin Educ Nurs. 2016, 47, 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauer, S.D.; Mangan, C.; Sanci, L. Do online mental health services improve help-seeking for young people? A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goldstein, F.; Glueck, D. Developing rapport and therapeutic alliance during telemental health sessions with children and adolescents. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, K.; Comer, J.S. The case for telemental health for improving the accessibility and quality of children’s mental health services. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sasser, T.; Schoenfelder Gonzalez, E.; Vander Stoep, A.; Myers, K. Implementation of home-based telemental health in a large child psychiatry department during the covid-19 crisis. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 30, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, R.M.; Ferng-Kuo, S.F.; Rahmouni, H.; Hardesty, D. Telehealth increases access to care for children dealing with suicidality, depression, and anxiety in rural emergency departments. Telemed. J. E Health 2020, 26, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hilty, D.M.; Crawford, A.; Teshima, J.; Chan, S.; Sunderji, N.; Yellowlees, P.M.; Kramer, G.; O’neill, P.; Fore, C.; Luo, J.; et al. A framework for telepsychiatric training and e-health: Competency-based education, evaluation and implications. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, D.M.; Chan, S.; Torous, J.; Luo, J.; Boland, R. A telehealth framework for mobile health, smartphones and apps: Competencies, training and faculty development. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2019, 4, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loncar-Turukalo, T.; Zdravevski, E.; Machado da Silva, J.; Chouvarda, I.; Trajkovik, V. Literature on wearable technology for connected health: Scoping review of research trends, advances, and barriers. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, D.M.; Zalpuri, I.; Torous, J.; Nelson, E.L. Child and adolescent asynchronous technology competencies for clinical care and training: Scoping review. Fam. Syst. Health 2020, 39, 121–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odgers, C.L.; Jensen, M.R. Annual Research Review: Adolescent mental health in the digital age: Facts, fears, and future directions. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 2020, 61, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, L.; Perrotta, S.; LaGrassa, J.; Merikangas, K.; Kreindler, D.; Kundur, D.; Courtney, D.; Szatmari, P.; Battaglia, M.; Strauss, J. Mobile and wearable technology for mon- itoring depressive symptoms in children and ado- lescents: A scoping review. JAD 2020, 265, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, M.A.; Gajos, J.M. Annual Research Review: Ecological momentary assessment studies in child psychology and psychiatry. J. Child. Psychol Psychiatry 2020, 61, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemer, C.P.; Fogel, J.; Van Voorhees, B.W. Telemental health and web-based applications in children and adolescents. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 20, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coughtrey, A.E.; Pistrang, N. The effectiveness of telephone-delivered psychological therapies for depression and anxiety: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboujaoude, E.; Salame, W.; Naim, L. Telemental health: A status update. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abuwalla, Z.; Clark, M.D.; Burke, B.; Tannenbaum, V.; Patel, S.; Mitacek, R.; Gladstone, T.; Van Voorhees, B. Long-term telemental health prevention interventions for youth: A rapid review. Internet Interv. 2017, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscos, T.; Carpenter, M.; Drouin, M.; Roebuck, A.; Kerrigan, C.; Mirro, M. College students’ experiences with, and willingness to use, different types of telemental health resources: Do gender, depression/anxiety, or stress levels matter? Telemed. J. E Health 2018, 24, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloff, N.E.; LeNoue, S.R.; Novins, D.K.; Myers, K. Telemental health for children and adolescents. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, J.M.; Birrell, E.; Bismark, M.; Pirkis, J.; Davenport, T.A.; Hickie, I.B.; Weinberg, M.K.; Ellis, L.A. The role of technology in Australian youth mental health reform. Aust. Health Rev. 2016, 40, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt, K. Tele-mental health for children: Using videoconferencing for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Telemedicine Association. Practice Guideline for Child and Adolescent Telemental Health. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health. 2017. Available online: https://www.cdphp.com/-/media/files/providers/behavioral-health/hedis-toolkit-and-bh-guidelines/practice-guidelines-telemental-health.pdf?laen (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Dwyer, T.F. Telepsychiatry: Psychiatric consultation by interactive television. Am. J. Psychiatry 1973, 130, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marasinghe, R.B.; Edirippulige, S.; Kavanagh, D.; Smith, A.; Jiffry, M.T. Effect of mobile phone-based psychotherapy in suicide prevention: A randomized controlled trial in Sri Lanka. J. Telemed. Telecare 2012, 18, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, K.A.; Chappel, S.E.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Ball, K.; Brown, H.; Macfarlane, S.; Ridgers, N.D. Parental Perspectives of a Wearable Activity Tracker for Children Younger Than 13 Years: Acceptability and Usability Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e13858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, M.S.; Kendall, P.C. Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spence, S.H.; Donovan, C.L.; March, S.; Gamble, A.; Anderson, R.E.; Prosser, S.; Kenardy, J. A randomized controlled trial of online versus clinic-based CBT for adolescent anxiety. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donovan, C.L.; March, S. Online CBT for preschool anxiety disorders: A randomized control trial. Behav. Res. Therapy 2014, 58, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.J.; Rapee, R.M.; Salim, A.; Goharpey, N.; Tamir, E.; McLellan, L.F.; Bayer, J.K. Internet-delivered parenting program for prevention and early intervention of anxiety problems in young children: Randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adol. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- March, S.; Spence, S.H.; Donovan, C.L. The efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for child anxiety disorders. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spence, S.H.; Holmes, J.M.; March, S.; Lipp, O.V. The feasibility and outcome of clinic plus internet delivery of cognitive-behavior therapy for childhood anxiety. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.J.; Wuthrich, V.M.; Rapee, R.M.; Lyneham, H.J.; Schniering, C.A.; Hudson, J.L. The Cool Teens CD-ROM for anxiety disorders in adolescents: A pilot case series. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 18, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuthrich, V.M.; Rapee, R.M.; Cunningham, M.J.; Lyneham, H.J.; Hudson, J.L.; Schniering, C.A. A randomized cintrolled trial of the Cool Teens CD-ROM computerized program for adolescent anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 51, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillfors, M.; Andersson, G.; Ekselius, L.; Furmark, T.; Lewenhaupt, S.; Karlsson, A.; Carlbring, P. A randomized trial of Internet-delivered treatment for social anxiety disorder in high school students. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011, 40, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, V.; McGrath, P.J.; Wojtowicz, M. Internet-based guided self-help for university students with anxiety, depression and stress: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.; Batterham, P.; Mackinnon, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Kalia Hehir, K.; Kenardy, J.; Gosling, J.; Bennett, K. Prevention of generalized anxiety disorder using a web intervention, iChill: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calear, A.L.; Batterham, P.J.; Poyser, C.T.; Mackinnon, A.J.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Cluster randomised controlled trial of the e-couch Anxiety and Worry program in schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 196, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Voogd, E.L.; Wiers, R.W.; Prins, P.; de Jong, P.J.; Boendermaker, W.J.; Zwitser, R.J.; Salemink, E. Online attentional bias modification training targeting anxiety and depression in unselected adolescents: Short- and long-term effects of a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Therapy 2016, 87, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Voogd, E.L.; Wiers, R.W.; Salemink, E. Online visual search attentional bias modification for adolescents with heightened anxiety and depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Therapy 2017, 92, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Voogd, L.; Wiers, R.W.; de Jong, P.J.; Zwitser, R.J.; Salemink, E. A randomized controlled trial of multi-session online interpretation bias modification training: Short- and long-term effects on anxiety and depression in unselected adolescents. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, A.L.; Pincus, D.B.; Furr, J.M.; Comer, J.S. Working From Home: An Initial Pilot Examination of Videoconferencing-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxious Youth Delivered to the Home Setting. Behav. Ther. 2018, 49, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novella, J.K.; Ng, K.M.; Samuolis, J. A comparison of online and in-person counseling outcomes using solution-focused brief therapy for college students with anxiety. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulgoni, C.; Melvin, G.A.; Jorm, A.F.; Lawrence, K.A.; Yap, M. The Therapist-assisted Online Parenting Strategies (TOPS) program for parents of adolescents with clinical anxiety or depression: Development and feasibility pilot. Internet Interv. 2019, 18, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calear, A.L.; Christensen, H.; Mackinnon, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; O’Kearney, R. The YouthMood Project: A cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E.L.; Barnard, M.; Cain, S. Treating childhood depression over videoconferencing. Telemed. J. e-Health 2004, 9, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinghurst, S.; Peters, T.J.; Kaur, S.; Wiles, N.; Lewis, G.; Kessler, D. Cost-effectiveness of therapist-delivered online cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zanden, R.; Kramer, J.; Gerrits, R.; Cuijpers, P. Effectiveness of an online group course for depression in adolescents and young adults: A randomized trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldofski, S.; Kohls, E.; Bauer, S.; Becker, K.; Bilic, S.; Eschenbeck, H.; Kaess, M.; Moessner, M.; Salize, H.J.; Diestelkamp, S.; et al. ProHEAD consortium. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of two online interventions for children and adolescents at risk for depression (E.motion trial): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial within the ProHEAD consortium. Trials 2019, 20, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kearney, R.; Gibson, M.; Christensen, H.; Griffiths, K.M. Effects of a cognitive-behavioural internet program on depression, vulnerability to depression and stigma in adolescent males: A school-based controlled trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2006, 35, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kearney, R.; Kang, K.; Christensen, H.; Griffiths, K. A controlled trial of a school-based Internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depress. Anxiety 2009, 26, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J.; Conijn, B.; Oijevaar, P.; Riper, H. Effectiveness of a web-based solution-focused brief chat treatment for depressed adolescents and young adults: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Voorhees, B.W.; Vanderplough-Booth, K.; Fogel, J.; Gladstone, T.; Bell, C.; Stuart, S.; Gollan, J.; Bradford, N.; Domanico, R.; Fagan, B.; et al. Integrative internet-based depression prevention for adolescents: A randomized clinical trial in primary care for vulnerability and protective factors. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 17, 184–196. [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees, B.W.; Fogel, J.; Reinecke, M.A.; Gladstone, T.; Stuart, S.; Gollan, J.; Bradford, N.; Domanico, R.; Fagan, B.; Ross, R.; et al. Randomized clinical trial of an Internet-based depression prevention program for adolescents (Project CATCH-IT) in primary care: 12-week outcomes. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2009, 30, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoek, W.; Marko, M.; Fogel, J.; Schuurmans, J.; Gladstone, T.; Bradford, N.; Domanico, R.; Fagan, B.; Bell, C.; Reinecke, M.A.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of primary care physician motivational interviewing versus brief advice to engage adolescents with an Internet-based depression prevention intervention: 6-month outcomes and predictors of improvement. Transl. Res. 2011, 158, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saulsberry, A.; Marko-Holguin, M.; Blomeke, K.; Hinkle, C.; Fogel, J.; Gladstone, T.; Bell, C.; Reinecke, M.; Corden, M.; Van Voorhees, B.W. Randomized Clinical Trial of a Primary Care Internet-based Intervention to Prevent Adolescent Depression: One-year Outcomes. J. Canad Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry=J. de l’Academie Can. de Psychiatr. de l’enfant et de L’Adolescent. 2013, 22, 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.; Hetrick, S.; Cox, G.; Bendall, S.; Yung, A.; Pirkis, J. The safety and acceptability of delivering an online intervention to secondary students at risk of suicide: Findings from a pilot study. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2015, 9, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickhi, B.; Kania-Richmond, A.; Moritz, S.; Cohen, J.; Paccagnan, P.; Dennis, C.; Liu, M.; Malhotra, S.; Steele, P.; Toews, J. Evaluation of a spirituality informed e-mental health tool as an intervention for major depressive disorder in adolescents and young adults-a randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstone, P.H.; Bercov, M.; Suen, V.Y.; Allen, A.; Cribben, I.; Goodrick, J.; Henry, S.; Pryce, C.; Langstraat, P.; Rittenbach, K.; et al. Initial Findings from a Novel School-Based Program, EMPATHY, Which May Help Reduce Depression and Suicidality in Youth. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, S.; Gleeson, J.; Davey, C.; Hetrick, S.; Parker, A.; Lederman, R.; Wadley, G.; Murray, G.; Herrman, H.; Chambers, R.; et al. Moderated online social therapy for depression relapse prevention in young people: Pilot study of a ‘next generation’ online intervention. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2018, 12, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deady, M.; Mills, K.L.; Teesson, M.; Kay-Lambkin, F. An Online Intervention for Co-Occurring Depression and Problematic Alcohol Use in Young People: Primary Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, P.; Chim, D.; Chan, K.L.; Li, T.M.; Ho, F.K.; Van Voorhees, B.W.; Tiwari, A.; Tsang, A.; Chan, C.W.; Ho, M.; et al. Effectiveness of a culturally attuned Internet-based depression prevention program for Chinese adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poppelaars, M.; Tak, Y.R.; Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A.; Engels, R.C.; Lobel, A.; Merry, S.N.; Lucassen, M.F.; Granic, I. A randomized controlled trial comparing two cognitive-behavioral programs for adolescent girls with subclinical depression: A school-based program (Op Volle Kracht) and a computerized program (SPARX). Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 80, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stallman, H.M.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Arklay, A.R.; Bennett-Levy, J. Randomised Control Trial of a Low-Intensity Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy Intervention to Improve Mental Health in University Students. Aust. Psychol. 2016, 51, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.B.; Kass, A.E.; Trockel, M.; Cunning, D.; Weisman, H.; Bailey, J.; Sinton, M.; Aspen, V.; Schecthman, K.; Jacobi, C.; et al. Reducing eating disorder onset in a very high risk sample with significant comorbid depression: A randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arensman, E.; Koburger, N.; Larkin, C.; Karwig, G.; Coffey, C.; Maxwell, M.; Harris, F.; Rummel-Kluge, C.; Van Audenhove, C.; Sisask, M.; et al. Depression Awareness and Self-Management Through the Internet: Protocol for an Internationally Standardized Approach. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2015, 4, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, A.; Larocca, R.; Chang, T.; Trinh, N.H.; Fava, M.; Kvedar, J.; Yeung, A. Web-based depression screening and psychiatric consultation for college students: A feasibility and acceptability study. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2014, 580786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Storch, E.A.; Caporino, N.E.; Morgan, J.R.; Lewin, A.B.; Rojas, A.; Brauer, L.; Larson, M.J.; Murphy, T.K. Preliminary investigation of web-camera delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 189, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, J.S.; Furr, J.M.; Kerns, C.E.; Miguel, E.; Coxe, S.; Elkins, R.M.; Carpenter, A.L.; Cornacchio, D.; Cooper-Vince, C.E.; DeSerisy, M.; et al. Internet-delivered, family-based treatment for early-onset OCD: A pilot randomized trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himle, J.A.; Fischer, D.J.; Muroff, J.R.; Van Etten, M.L.; Lokers, L.M.; Abelson, J.L.; Hanna, G.L. Videoconferencing-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1821–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, P.A.; Launes, G.; Moen, E.M.; Solem, S.; Hansen, B.; Håland, A.T.; Himle, J.A. Videoconference- and cell phone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A case series. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetter, E.M.; Herbert, J.D.; Forman, E.M.; Yuen, E.K.; Thomas, J.G. (2014). An open trial of videoconference-mediated exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 460–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, F.; Vigerland, S.; Andersson, E.; Rück, C.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Thulin, U.; Ljótsson, B.; Serlachius, E. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: An open trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.M.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Lovell, K.; Krebs, G.; Lang, K.; Byford, S.; Heyman, I. Telephone cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, L.H.; Weidle, B.; Babiano-Espinosa, L.; Skokauskas, N. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Effectiveness of Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (eCBT) for Children and Adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Protocol for an Open Trial and Therapeutic Intervention. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e24057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, D.S.; Manassis, K.; Kenny, A.; Fiksenbaum, L. Web-based CBT for selective mutism. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comer, J.S.; Elkins, R.M.; Chan, P.T.; Jones, D.J. New methods of service delivery for children’s mental health care. In Comprehensive Evidence-Based Interventions for School-Aged Children and Adolescents; Alfano, C.A., Beidel, D., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vliet, H.V.; Andrews, G. Internet-based course for the management of stress for junior high schools. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.J. Future directions in the design, development, and investigation of technology as a service delivery vehicle. J. Clin. Child. Adol. Psychol. 2014, 43, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comer, J.S.; Furr, J.M.; Miguel, E.M.; Cooper-Vince, C.E.; Carpenter, A.L.; Elkins, R.M.; Kerns, C.E.; Cornacchio, D.; Chou, T.; Coxe, S.; et al. Remotely delivering real-time parent training to the home: An initial randomized trial of Internet-delivered parent-child interaction therapy (I-PCIT). J. Consult. Clin. Psychology 2017, 85, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscos, T.; Coupe, A.; Flanagan, M.; Drouin, M.; Carpenter, M.; Reining, L.; Roebuck, A.; Mirro, M.J. Teens using screens for help: Impact of suicidal ideation, anxiety, and depression levels on youth preferences for telemental health resources. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stasiak, K.; Fleming, T.; Lucassen, M.F.; Shepherd, M.J.; Whittaker, R.; Merry, S.N. Computer-Based and Online Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Kleiboer, A.; Karyotaki, E.; Riper, H. Internet and mobile interventions for depression: Opportunities and challenges. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, E.; Sander, C.; Wagner, X.; Hegerl, U.; Kohls, E. Smartphone-Based Monitoring of Objective and Subjective Data in Affective Disorders: Where Are We and Where Are We Going? Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilty, D.M.; Shoemaker, E.Z.; Myers, K.; Snowdy, C.E.; Yellowlees, P.M.; Yager, J. Need for and steps toward a clinical guideline for the telemental health care of children and adolescents. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigerland, S.; Serlachius, E.; Thulin, U.; Andersson, G.; Larsson, J.O.; Ljotsson, B. Long-term outcomes and predictors of internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. Behav. Res. Therapy 2017, 90, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, M.H.; Comer, J.S.; Gonzalez, J. Delivering parent-teen therapy for ADHD through videoconference: A preliminary investigation. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2017, 39, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, S.; Malas, N.; Dopp, R.; Quigley, J.; Kramer, A.C.; Tengelitsch, E.; Patel, P.D. The michigan child collaborative care program: Building a telepsychiatry consultation service. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscos, T.; Carpenter, M.; Drouin, M.; Roebuck, A.; Howard, A.; Flanagan, M.; Kerrigan, C. Using immediate response technology to gather electronic health data and promote telemental health among youth. EGEMS 2018, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- American Telemental Health Association Practice Guidelines for Videoconferencing Based Telemental Health. ATA. 2009. Available online: http://www.americantelemed.org/files/public/standards/PracticeGuidelinesforVideoconferencing-Based%20TelementalHealth.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- American Telemental Health Association. Expert Consensus Recommendations for Videoconferencing-Based Telepresenting. ATA. 2011. Available online: http://www.americantelemed.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid53311 (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Shore, J.H.; Yellowlees, P.; Caudill, R.; Johnston, B.; Turvey, C.; Mishkind, M.; Krupinski, E.; Myers, K.; Shore, P.; Kaftarian, E.; et al. Best practices in videoconferencing-based telemental health April 2018. Telemed. J. E Health 2018, 24, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Telepsychiatry and AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Clinical update: Telepsychiatry with children and adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AACAP-APA Child and Adolescent Telepsychiatry Toolkit. 2019. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/child-adolescent (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Crawford, A.; Sunderji, N.; Lopez, J.; Soklaridis, S. Defining competencies for the practice of telepsychiatry through an assessment of resident learning needs. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elford, R.; White, H.; Bowering, R.; Ghandi, A.; Maddiggan, B.; John, K.S. A randomized, controlled trial of child psychiatric assessments conducted using videoconferencing. J. Telemed. Telecare 2000, 6, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elford, D.R.; White, H.; John, K.S.; Maddigan, B.; Ghandi, M.; Bowering, R. A prospective satisfaction study and cost analysis of a pilot child telepsychiatry service in Newfoundland. J. Telemed. Telecare 2001, 7, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, K.M.; Stoep, A.V.; Klein, J.B.; Palmer, N.B.; Geyer, J.R.; Melzer, S.M.; McCarty, C.A. Child and adolescent telepsychiatry: Variations in utilization, referral patterns and practice trends. J. Telemed. Telecare 2010, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, K.; Nelson, E.-L.; Rabinowitz, T.; Hilty, D.; Baker, D.; Barnwell, S.S.; Boyce, G.; Bufka, L.F.; Cain, S.; Chui, L.; et al. American telemedicine association practice guidelines for telemental health with children and adolescents. Telemed. J. E Health 2017, 23, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 10601073. [Google Scholar]

| Psychiatric Evaluation |

|

| Psychiatric Crisis service |

|

| Initial Outpatient Visit |

|

| Established Outpatient Visit |

|

| Teletherapy |

|

| Study | Sample Features | Intervention | Advantages | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ||||

| [29] | 49 children (M 33; F 16), aged 7–13 yy, with a principal anxiety disorder |

| Findings support the feasibility, acceptability and beneficial effects of CCAL for anxious youth. |

|

| [30] | 115 clinically anxious adolescent, aged 12 to 18 yy (M 47; F 68) and their parents |

| Online CBT, with minimal therapist contact, for adolescent anxiety disorders offer an efficacious alternative to clinic-based treatment. |

|

| [31] | 52 pre-school r children (M 24; F 28), aged 3–6 yy, with clinical anxiety disorders (ADIS-C) |

|

|

|

| [32] | 433 parents of children aged 3 to 6 yy, with an inhibited temperament (OAPA) |

|

|

|

| [33] | 73 children (33 M; 40 F) with anxiety disorders (ADIS-C/P), aged 7–12 yy, and their parents. |

|

|

|

| [34] | 72 clinically anxious children (M 42; F 30), aged 7–14 yy |

| The internet treatment content was highly acceptable to families, with minimal dropout and a high level of therapy compliance. |

|

| [35] | 5 adolescents (M 1; F 4), aged 14–16 yy, with anxiety disorder (ADIS-C) |

| Participants were generally satisfied with multimedia content, the modules and the delivery format of the program. |

|

| [36] | 43 adolescents (M 16; F 27), aged 17–17 yy, with primary diagnosis of anxiety (ADIS-C/P & SCAS-C/P) |

| The Cool Teens program is an efficacious option for the treatment of adolescent anxiety. |

|

| [37] | 19 high school students, aged 15–21 yy, with social anxiety disorder (SPSQ-C & MADRS-S) |

| Internet-delivered CBT could be an option to treat high school students although strategies to increase compliance should be found. |

|

| [38] | 66 distressed university students (DASS-21) |

| An individual-adaptable, internet-based, self-help programs can reduce psychological distress in university students. |

|

| [39] | 558 internet users, recruited via the Australian Electoral Roll | The sample was randomly assigned to 5 arms:

| This trial is not able to demonstrate the preventative effects of the website on anxiety symptoms as measured by the GAD-7. |

|

| [40] | A three-arm cluster stratified randomised controlled trial take in consideration 1767 students (M 37.2%; F 62.8%) about anxiety disorder |

| The e-couch Anxiety and Worry program did not have a significant positive effect on participants. |

|

| [41] | 340 adolescents (M 42.4%; F 57.6%), aged 11–18 yy, recruited from 14 regular high schools in the Netherlands | To evaluate the efficacy of CBM-A, the sample was randomly allocated to eight sessions of a dot-probe (DP), or a visual search-based (VS) attentional training, or one of two corresponding placebo control conditions and received 8 sessions of an online training over four weeks. | More research is needed to investigate and improve the efficacy of CBM-A in adolescents. |

|

| [42] | 108 adolescents (M 33.3%; F 66.7%), aged 11–19 yy, with symptoms of anxiety and/or depression (SCARED & CDI) | The current study investigated the effects of eight online sessions of visual search (VS) ABM, following four weeks, compared to both a VS placebo-training and a no-training control group online training sessions. | There is no evidence for the efficacy of online visual search ABM in reducing anxiety or depression or increasing emotional resilience in selected adolescents. |

|

| [43] | 173 participants |

| Results suggest that interpretation training as implemented in this study has no added value in reducing symptoms or enhancing resilience in unselected adolescents. |

|

| [44] | 13 youth (M 6; F 7), aged 8–13 yy, with a primary/co-primary anxiety disorder diagnosis and their mothers |

| Videoconferencing treatment formats may serve to improve the quality care of youth anxiety disorders. |

|

| [45] | 49 undergraduate students (M 4; F 45) who were seeking counseling for mild to moderate anxiety |

| The findings provide support for the treatment of college students with anxiety with SFBT through online, synchronous video counseling. |

|

| [46] | Develop a Therapist-assisted Online Parenting Strategies (TOPS) program that is acceptable to parents whose adolescents have anxiety and/or depressive disorders, using a consumer consultation approach | TOPS intervention was developed via three linked studies.

| This study provided preliminary support for the feasibility, acceptability and perceived usefulness of the TOPS program |

|

| Depression | ||||

| [9] | Observational an 18-month program for children less than 18 years (n = 87) who received physical and mental health assessment by ED physician | Wabash Valley Rural Telehealth Network utilizes an on-demand design with a centralized “hub” of medical providers that delivers specialty based psychiatric care via a regional telehealth network. | Decreasing waiting time in ED for those children and adolescents who need a CAP specialist in remote areas without CAP. |

|

| [47] | 1477 students (M 651; F 826), aged 12–17 yy, from 32 schools across Australia |

| Although small to moderate, the effects obtained in the current study provide support for the utility if prevention programs in schools. |

|

| [48] | 38 families e 28 children (20 M; 6 F), aged 8–14 yy, with childhood depression (K-SADS-P & CDI) |

| NA |

|

| [49] | 297 patients (M 32%; F 68%), aged 18–75 yy, having a new episode of depression (BDI & CIS-R) |

| This type of therapy appeals in particular to those who like to write their feelings down, those who value the opportunity to review and reflect on the dialogue of the therapy session, and those who prefer the anonymity offered by this method of delivering CBT.It could be an alternative to face-to-face treatment for those whose first language is not English.The intervention may also be useful when traveling is difficult or expensive because of rurality, disability or social phobia. |

|

| [50] | 244 young people, aged 16–25 yy, with depressive symptoms (CES-D) |

| MYM course was effective in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms and increasing mastery in young people. |

|

| [51] | 363 children and adolescents, aged ≥ 12 yy, with subsyndromal symptoms of depression (PHQ-A) recruited at five sites across Germany, by the German ProHEAD consortium. |

|

| |

| [52] | 79 boys, aged 15–16 yy |

| Considering the high drop-out rate there is the need to review the appropriateness and difficulty of the material as well as the formats used in Internet programs. |

|

| [53] | 157 girls, aged 15–16 yy, come from a single sex school in Canberra, Australia | Students were allocated to undertake either MoodGYM or their usual curriculum. |

|

|

| [54] | 263 young individuals aged 12–22 yy with depressive symptoms (CES-D) |

| Chat condition demonstrated a reliable and clinically significant improvement at 4.5 months, but not yet at 9 weeks. |

|

| [55] | 84 adolescents, aged 14–21 yy, at risk for developing major depression (PHQ-A) were selected through the CATCH-IT project |

| In the BA condition, the physician takes a directive approach and advises the adolescent that he is experiencing a depressed mood and refers the adolescent to the CATCH-IT internet site. |

|

| [56] | 84 adolescents, aged 14–24 yy, recruited when they visited the primary care provider for risk of depressive disorder, as well as through advertisements posted in and around the clinics. |

| This tool may help extend the services at the disposal of a primary care provider and can provide a bridge for adolescents at risk for depression. |

|

| [57] | 84 participants (M 43.4%, F 56.6%), with mean age of 17.47 yy, were recruited by screening for risk of depression in 13 primary care practices |

| It would be useful to make these interventions more accessible to adolescents given their good effectiveness. |

|

| [58] | 83 adolescents recruited from 12 primary care sites across Southern and Midwestern United States |

| The tool may help extend the services at the disposal of a primary care provider and can provide a bridge for adolescents at risk for depression. |

|

| [59] | 34 students were recruited from nine schools | A pilot study employed a pre-test/post-test design with 8-week intervention based on the Reframe Internet-based program interventions. It consists of 8 modules, based on CBT, each of which takes around 10–20 min to complete. | The finding are promising and suggest that young people at risk of suicide can safely be included in trials as long as adequate safety procedures are in place. |

|

| [60] | 62 participants with major depressive disorder were defined by two age subgroups: adolescents (n = 31), aged 13–18 yy (CDRS-R), and young adults (n = 32), aged 19–24 yy (HAMD). |

| Spirituality is increasing as an important consideration in mental Health and mental health interventions. |

|

| [61] | 3224 youth (M 1676; F 1568), aged 11–18 yy, selected from 5 schools in the Red Deer Public School system |

| Suggesting that a multimodal school-based program may provide an effective and pragmatic approach to help reduce youth depression and suicidality. |

|

| [62] | 42 youth (M 22; F22), aged 15–25 yy, affected by depression in partial or full remission |

| These types of online social networking are well appreciated by the young people, and further studies would be needed to perfect their development. |

|

| [63] | 104 participants, aged 18–25 yy, with moderate depression symptomatology (DASS-21) and use of alcohol at hazardous levels (AUDIT) |

| DEAL Project it could be a good option for patients with both depression symptoms and alcohol use. |

|

| [64] | 257 Chinese adolescents, aged 13–17 yy, with mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms were recruited from three secondary schools in Hong Kong |

| Poor completion rate is the major challenge in the study. |

|

| [65] | 208 Dutch female adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms (RADS-2) |

| Videogames could be a good strategy to improve the compliance of adolescents for computerized CBT. |

|

| [66] | 107 participants (M 8%, F 92%), aged 17–48 yy, recruited at The University of Queensland Health Service |

| It could be useful to introduce LI-CBT in the university system, even if further studies are needed. |

|

| [67] | 206 female students, aged 18–25 yy, at very high risk for eating disorder onset (WCS) |

| IaM is an inexpensive, easy intervention that can reduce ED onset in high-risk women. |

|

| [68] | Web-based awareness and self-management protocol to mild-to-moderate depression |

| Protocol for the development, implementation and evaluation of the iFight Depression tool, cost-free, multilingual, guided, self-management program for mild-to-moderate depression cases. |

|

| [69] | 927 students, enrolled in universities in Massachusetts, were recruited to join the web-based screening survey for depression. |

| Current online technologies can provide depression screening and psychiatric consultation to college students. |

|

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | ||||

| [70] | 31 youth (19 M; 12 F), aged 7–16 yy, with OCD (CY-BOCS & ADIS-C/P) |

| This preliminary study suggests the possible role of W-CBT in reducing OC symptoms in youth with OCD. |

|

| [71] | 22 child (13 M; 9 F), aged 4–8 yy, with OCD (ADIS-C/P & CY-BOCS) |

| VTC methods may offer solutions to overcoming traditional barriers to care for early-onset OCD. |

|

| [72] | 3 female patients with a story of OCD |

| Manualized CBT for OCD can be effectively delivered via a VC network. |

|

| [73] | 6 patients (M 1; F 5) with history of OCD (ADIS) |

| Internet-delivery CBT may be a promise method treatment for OCD patients. |

|

| [74] | 15 adults (M 13.3%; F 86.7%) with OCD |

| This study adds to the growing body of literature suggesting that videoconference-based interventions are viable alternatives to face-to-face treatment. |

|

| [75] | 21 participants, aged 12–17 yy, with OCD (MINI-KID) and their parents |

| ICBT could be efficacious, acceptable and cost-effective for adolescents with OCD. |

|

| [76] | 72 adolescents, aged 11–18 yy, with OCD and their parents |

| TCBT is an effective treatment and is not inferior to standard clinic-based CBT. |

|

| [77] | 30 children, aged 7-17, with primary diagnosis of OCD, and their parents |

| NA |

|

| Basic technical/IT skills |

|

| Assessment skills in TMH |

|

| Relational skills in TMH |

|

| Communication skills in TMH |

|

| Collaborative and inter-professional skills in TMH |

|

| Administrative skills in TMH |

|

| Medico-legal competencies and skills in TMH |

|

| Ethno- and cultural psychiatry skills in TMH |

|

| General knowledge and experience about TMH |

|

| General notions about TMH |

|

| Specific notions about the efficacy and effectiveness of TMH interventions |

|

| Explanation on how TMH works |

|

| Clarification about recording TMH session |

|

| Establishing a visual context (i.e., setting) of TMH session |

|

| Discussing how to manage occurring technical issues |

|

| Offering a space for open questions |

|

| Obtain informed consent |

|

| Obtain written and signed emergency shared plan |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orsolini, L.; Pompili, S.; Salvi, V.; Volpe, U. A Systematic Review on TeleMental Health in Youth Mental Health: Focus on Anxiety, Depression and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Medicina 2021, 57, 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080793

Orsolini L, Pompili S, Salvi V, Volpe U. A Systematic Review on TeleMental Health in Youth Mental Health: Focus on Anxiety, Depression and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Medicina. 2021; 57(8):793. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080793

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrsolini, Laura, Simone Pompili, Virginio Salvi, and Umberto Volpe. 2021. "A Systematic Review on TeleMental Health in Youth Mental Health: Focus on Anxiety, Depression and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder" Medicina 57, no. 8: 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080793

APA StyleOrsolini, L., Pompili, S., Salvi, V., & Volpe, U. (2021). A Systematic Review on TeleMental Health in Youth Mental Health: Focus on Anxiety, Depression and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Medicina, 57(8), 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57080793