Abstract

Background and objective: Traditional medicine (TM) was integrated into health systems in Africa due to its importance within the health delivery setup in fostering increased health care accessibility through safe practices. However, the quality of integrated health systems in Africa has not been assessed since its implementation. The objective of this paper was to extensively and systematically review the effectiveness of integrated health systems in Africa. Materials and Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted from October, 2019 to March, 2020 using Ovid Medline, Scopus, Emcare, Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), and Google Scholar, in order to retrieve original articles evaluating the integration of TM into health systems in Africa. A quality assessment of relevant articles was also carried out using the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATDSS) critical appraisal tool. Results: The results indicated that the formulation and execution of health policies were the main measures taken to integrate TM into health systems in Africa. The review also highlighted relatively low levels of awareness, usage, satisfaction, and acceptance of integrated health systems among the populace. Knowledge about the existence of an integrated system varied among study participants, while satisfaction and acceptance were low among orthodox medicine practitioners. Health service users’ satisfaction and acceptance of the practice of an integrated health system were high in the countries assessed. Conclusion: The review concluded that existing health policies in Africa are not working, so the integration of TM has not been successful. It is critical to uncover the barriers in the health system by exploring the perceptions and experiences of stakeholders, in order to develop solutions for better integration of the two health systems.

1. Introduction

Traditional medicine (TM) refers to the sum total of all explicable knowledge and practices used in the diagnosis, prevention, and elimination of physical, mental, and social imbalance. TM exclusively relies on practical experience and observations handed down verbally or in writing from generation to generation [1]. TM’s use is increasing in both developed and developing countries. For example, the proportion of residents who have patronised TM at least once in developed countries is 38% in Belgium, 42% in the United States of America, 48% in Australia, 70% in Canada, and 75% in France [2]. TM use is reported to be more popular in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, since 80% of the population continue to depend on TM for their primary health care needs [2,3]. The high frequency of TM use in Africa has been attributed to reasons such as TM being economical, and socially and culturally acceptable within the African setting [4,5,6]. Additionally, TM has proven to be effective in managing and treating tropical maladies and other ailments, such as epilepsy, hypertension, insomnia, ovarian cancer, convulsion, stroke, boils, tuberculosis, infertility, hernia, and malaria, among others [3,6,7]. In Nigeria, for instance, Rauwolfia vomitoria, a medicinal herb in the Apocynaceae family, is used to manage disease conditions such as insomnia, convulsion, stroke, and hypertension [3]. Traditional birth attendants in South Africa use TM with muscle relaxant characteristics to help with the safe delivery of babies [3]. Aloe vera, black seed, black cohosh, and other TM plants are acknowledged for their outstanding health promotion and disease prevention benefits [8]. Studies have reported that TM continues to be an essential ingredient of a number of medications currently used for the management of heart diseases, fevers, pain therapies, and other health problems [3,9]. For instance, artemisinin, a derivative of the medicinal plant Artemisia annua, is the origin of a suite of efficient antimalarial drugs [3]. Recognition of the important role that TM plays in health delivery (its high prevalence and medicinal benefits) led to its integration into various health systems around the world, including those of Africa [4].

Integration has been defined as the act of broadening the scope of health delivery through communication, participation, accommodation, and partnership building between biomedical and traditional health systems, while safeguarding indigenous medical knowledge [10]. The sole purpose of an integrated health system is to offer quality health care to the population equally and satisfactorily, while averting unnecessary costs [11]. A booming integrated health system is likely to promote the proper use of indigenous medical knowledge and boost the development of health systems (self-adequacy), particularly in poor-income countries [12]. Asian countries such as Korea, Japan, China, India, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam have successfully integrated TM into their health system [12,13]. The practice of TM in these countries is founded on logical and comprehensive methods, as well as clinical experiences [13]. For example, in China, biomedical doctors are trained in the field of TM practice in order to support competent TM practitioners in health centers, embrace treatment processes based on TM principles, gain understanding from experienced TM practitioners, and study the curative effect of TM treatment with the diagnosis and model of the orthodox health system. This approach not only boosted the confidence of biomedical doctors in the field of TM, but also improved and sustained collaboration between the two health systems [13]. The Chinese success story in the field of integrated health is also illustrated by a rise in registered Chinese TM practitioners in the United States of America [14]. India has also boosted its integrated system through the incorporation of the repayment of medical costs incurred by utilizing TM products and services. Thereby, Indians who work in the public sector are reimbursed money spent on TM products and services [15].

African countries have also made efforts to integrate TM into formal health systems [4]. Such countries include Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, and the Republic of Congo, among others [10,16]. For example, Ghana instituted a council in the year 2010 to regulate the activities of TM practice and, in 2012, registered TM practitioners were allowed to practice medicine [17]. Similarly, Nigeria also formulated the National Policy on the TM Code of Ethics and the creation of national and state TM boards to oversee the practice, and boost partnership and research in the field of TM [18]. Most African countries ascribe to a parallel/inclusive model of health system integration. A parallel or inclusive model is a system where TM and biomedical health care are separate elements of the health system, but both are expected to interact and work jointly to deliver quality health services to clients [10,16]. However, the effectiveness of the integration of TM into health systems to offer quality health services to the African populace is unexplored. Therefore, this systematic review presents a comprehensive assessment of published literature on the effectiveness of integrated health systems in Africa. The primary measures of effectiveness in this study are the awareness, usage, satisfaction, and acceptance of an integrated health system among study populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining the ‘Integration of TM’

In this systematic review, TM integration refers to any research that has focused on the incorporation of herbal/indigenous medicines, including bonesetters, into health systems. Integrated health systems also include partnership between orthodox and traditional health service providers. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were adapted for this review [19]. A literature search was performed from October, 2019 to March, 2020 using Ovid Medline, Scopus, Emcare, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Web of Science, and Google Scholar to retrieve original articles on the integration of TM into health systems in Africa. Various keywords or synonyms were used in the search strategy to expand the search term because a number of terms have been used in the literature to refer to the same concept. Although the review is focused on the effectiveness of integrated health systems in Africa, the words ‘effective’ and ‘Africa’ were not included in the search terms to avoid restrictions of the search. Africa was precluded from the search term to avoid excluding articles reporting research conducted in Africa, but without the word ‘Africa’ in their titles. Minor differences existed in the search terms, depending on the type of database and search engine (Supplementary Table S1).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

There were no restrictions for the time and type of study, but the study setting was limited to Africa. Articles included in this systematic review are primary studies published in peer-reviewed journals reporting on measures taken to aid TM integration into health systems and the effectiveness of such integrated systems. Studies which referred to TM as herbal/indigenous medicine were selected for the review. The review excluded the following: Systematic reviews, theses, non-English articles, and other articles with animals as the target population.

2.3. Selection and Extraction of Data

I.G.A identified relevant articles and T.I.E replicated the search to confirm the search strategy. Uncertainties regarding the included studies were resolved by discussion, until a consensus was reached. The characteristics obtained from included studies were the target population, type of study, methodology, measures taken to integrate TM, summary of findings/results, and effectiveness of TM integration. However, interventions implemented to integrate TM into formal health systems were the key inclusion criteria.

2.4. Data Synthesis

The included studies were evaluated based on interventions implemented to integrate TM into formal health systems and key findings in relation to the effectiveness of the integrated health system. It is worth mentioning that the effectiveness was inferred from the findings and conclusions of various studies. This is because the effectiveness of integrated health systems was described, rather than explicitly stated, in the findings. Inference was conducted by evaluating the level of awareness, usage, satisfaction, and acceptance of the integration of TM among target populations. Awareness was inferred based on self-reported knowledge of the introduction of TM into the health system, while usage was deduced from the interactions between stakeholder groups (orthodox and TM practitioners, and health service users). Satisfaction was deduced on the basis of the fulfillment that participants derived from the system and acceptance was gleaned based on the value that participants placed on their role and the role of other stakeholders in the integration agenda. With quantitative studies, percentage scores correlating to inferred knowledge, usage, satisfaction, and acceptance which were less than or equal to 39% were deemed low [20], while values of 40% and above were assumed to be moderate/positive indicators [17]. Similar inferences were conducted for qualitative studies and representative quotes were used to support the inferences drawn.

2.5. Quality of Methods Assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) developed by Sirriyeh et al., was used to evaluate the quality of included studies [21]. The tool was adopted because it was applicable in all instances, since the review identified and included all types of studies. The tool is made up of 16 criteria and all the criteria were applicable to the mixed methods study, while qualitative and quantitative studies were assessed using fourteen 14 of these criteria. Each criterion on the list was allotted a score of zero to three, where 0 represents ‘criterion not mentioned at all’, 1 represents ‘very slightly mentioned’, 2 represents ‘criterion moderately stated’, and 3 represents a ‘vivid explanation’ of the criterion. In view of this, the highest mark for the mixed methods study was 48 (16 × 3) and 42 (14 × 3) was the highest mark for the qualitative and quantitative studies, respectively. The total scores of included studies were further converted to percentages. For example, a mixed methods study with a score 48 out of 48 equates to 100% (48/48 × 100 = 100). The percentage scores were further categorised into three groups such that an article was considered excellent if the percentage score was 80 and above, good if scores ranged between 50% and 79%, and low if the score was below 50%.

3. Results

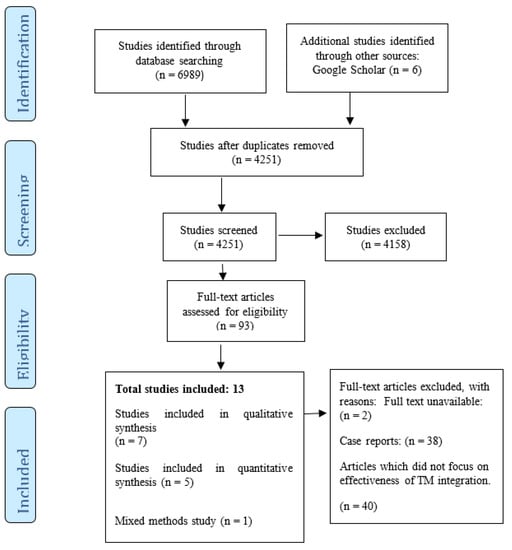

In total, 6995 articles were identified from five databases and the Google Scholar search. However, 2744 duplicates were removed, leaving 4251 articles. A total of 93 articles were retained after title and abstract screening. Thirteen out of the 93 articles met all of the inclusion criteria after full text screening (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA (The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) flow diagram of included studies [19].

3.1. Distribution of Reviewed Articles

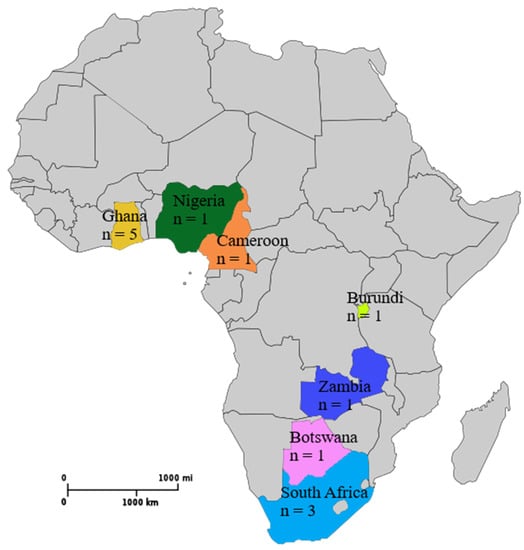

Thirteen articles were included in the review. Five (38.5%) of the articles originated from Ghana [12,17,22,23,24]. Three studies (23.1%) were conducted in South Africa [25,26,27]. The remaining five studies were carried out in Burundi [28], Botswana [20], Cameroon [29], Nigeria [30], and Zambia [31]. The reviewed studies were conducted over a period of thirteen years. The earliest study [31] was conducted in 2006, while the latest studies were carried out in 2019 [24,27]. Figure 2 shows the number of included studies from different countries in Africa.

Figure 2.

Map of Africa displaying the number of studies originating from various countries taken from Wikimedia Commons [32]. Accessed: 16 December 2019.

3.2. Characteristics of Reviewed Articles

Of the 13 included studies (Figure 1), seven were qualitative and five were quantitative studies. Only one was a mixed methods study. Two of the qualitative studies used a phenomenology approach (qualitative research which emphasizes similarities in lived experiences within a specific group of people) to achieve the study objectives [22,27], while one study [12] used an inductive reduction approach. Ethnography (qualitative research in which the researcher defines and interprets common and learnt forms of behavior, values, beliefs, and language of a culture-sharing group) was employed as research design for the qualitative aspect of the mixed methods study [28]. However, three of the qualitative studies did not state the research design used [23,25,26]. All quantitative studies used a cross-sectional design in achieving the study objectives [17,20,29,30,31].

As shown in Table 1, four studies targeted health practitioners and patients as study participants [12,22,25,28]. Two studies only focused on health practitioners [24,31]. Two other studies solely targeted TM practitioners [27,30], while another two focused on orthodox medicine practitioners (OMPs) [20,26]. One study assessed both TM practitioners and community members [29]. Another study also considered people interested in TM research as the target population [23]. The last reviewed article only targeted patients [17]. More focus was placed on TM practitioners, as nine of the included studies sampled TM health providers as study participants [12,22,24,25,27,28,29,30,31]. Only one study included key informants, consisting of the Faculty of Pharmacy (FOP), Ghana Federation of Traditional Medicine Practitioners (GFTMP), Medical Herbalist Association (MHA), Hospital Management (HM), and Pharmaceutical Directorate of Ministry of Health (PDMH), as part of the study group [22].

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies on the effectiveness of integrated health systems in Africa.

The sample size of quantitative articles ranged from 60 [20] to 6690 [28] participants. The most common sampling technique employed by quantitative studies was the convenient sampling procedure [20,29]. Other techniques used were systematic [17] and stratified sampling [28]. Two studies [30,31] failed to state the sampling techniques employed in choosing participants for the study. For qualitative studies, it ranged from 27 [27] to 37 participants [25]. The purposive sampling technique was widely used among qualitative studies [22,23,25,26]. Another sampling approach used was snowballing [12,28]. However, one study combined both snowballing and purposive sampling techniques in participant selection [24]. One qualitative study failed to mention the type of sampling technique employed in choosing participants for the study [27]. Generally, all reviewed articles assessed the perception, knowledge, acceptability, and satisfaction of study participants in relation to TM integration. The review inferred the effectiveness of integrated health systems on the premise of participants’ awareness, usage, satisfaction, and acceptability of TM integration into formal health systems. Twelve of the studies disclosed that integrated health systems in Africa were not effective [12,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Ineffective TM integration was appraised on the basis of a low level of participants’ knowledge about TM integration into health systems, minimal interaction among stakeholders within the integrated system, inadequate satisfaction derived from accessing or practicing in the system, and power imbalance within the integrated systems. Only a single study reported moderate/good indicators for the integrated health system among study participants [17].

3.3. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Integrated Health Systems in Africa

3.3.1. Interventions Implemented to Aid the Integration of TM into Health Systems in Africa

The official practice of TM started in the early 1980’s [29]. This means that the practice of an integrated health system in Africa has been in operation for approximately 39 years (Table 2). All reviewed articles acknowledged that TM integration was initiated through the formulation and execution of health policies [12,17,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Countries such as Burundi, Ghana, and South Africa went a step further by implementing other measures to facilitate the integration process. For example, in Burundi, the association of TM practitioners was formed and an integrative medicine unit was created in the Ministry of Health [28]. In Ghana, the government instituted the Traditional Medicine Practice Council (TMPC), established a TM directorate in the Ministry of Health, and introduced TM into the tertiary education system [12,17,23]. In South Africa, a council was created to oversee the activities of TM practitioners [27].

Table 2.

Studies on the effectiveness of integrated health systems in Africa.

3.3.2. Awareness as a Measure of an Effective Integrated Health System in Africa

Varying levels of awareness were observed among review articles. Seven studies reported a low level of awareness about the existence of integrated health systems in their countries [20,22,24,26,29,30,31]. For example, Kaboru, Falkenberg [31] recounted that a lower proportion (24%) of study participants claimed knowledge of the practice of an integrated health system in Zambia. A similar result was observed in the work of Madiba [20], where only 18.6% of participants knew of the integrated health system in Botswana. The knowledge gap was more profound in the area of availability of TM policy which regulates the activities of practitioners. However, six studies reported a moderate level of awareness among study participants [12,17,23,25,27,28]. For instance, a study conducted in Ghana reported that 42.2% of participants knew about the presence of TM units in the study sites [17] and 91% of orthodox medicine practitioners in Burundi were also aware of the integrated health system [28]. Participants attributed their source of knowledge to the interaction between traditional and orthodox health practitioners, but also admitted that integration was weak (Table 2).

3.3.3. Usage as a Measure of an Effective Integrated Health System in Africa

The usage of an integrated health system was inferred as the interaction between stakeholders (orthodox medicine practitioners, TM practitioners, and health care users) within the health system. A total of ten articles reported a low usage of the health system among study participants [12,20,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,30]. The usage of an integrated system was particularly low among orthodox practitioners, as only 27% of participants had ever collaborated with TM providers and 10% were willing to refer clients to TM providers [20]. The under-utilization of integrated health systems in Africa was attributed to the absence of protocol to publicize the integrated health system [22], TM products, and services not included in national health cover [23] and an unwillingness of orthodox practitioners to embrace the incorporation of TM practice into formal health systems [20,24]. Generally, inadequate evidence-based research to support TM practice was cited by orthodox practitioners as the reason for their resistance. Nonetheless, three studies reported a moderate usage of integrated health systems [17,25,31]. A Ghanaian study reported that 42.2% of participants patronized health services offered at the TM units in the study settings [17]. However, 13% of the participants stated that usage of the integrated system could increase through positive recommendations from orthodox practitioners. (Table 2). A study conducted in Zambia reported a moderate level of usage, as 53% of TM practitioners interacted with the formal health system by advising clients to access certain biomedical services, such as laboratory services, before they (TM practitioners) commenced treatment [31]. Usage was reported to be moderate in South Africa, as health service users patronized both health systems simultaneously or at different time periods, depending on the efficacy of treatment. For example, a participant stated, “We commenced treatment at orthodox health care, then progressed to TM providers but accessing TM worsened the ailment. So we stopped and returned to orthodox health care” [25].

3.3.4. Satisfaction as a Measure of an Effective Integrated Health System in Africa

Satisfaction was determined by the level of fulfilment that participants derived from integrated health systems. Ten reviewed articles reported a low level of satisfaction among participants [12,20,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Satisfaction was recounted to be minimal because 70% of participants were not pleased with TM practice [20]. This low satisfaction was mainly due to the failure of policy makers to enact and implement policies to promulgate the integration process, weak communication within the referral system between health care providers, and lopsided power relations within integrated health systems. However, one study reported that 53% of study participants were satisfied with the integrated health system because their preference for TM had increased due to its operation in health centres [17]. Another study reported varying levels of satisfaction among participants. The variation ranged from ‘being satisfied with the system’ (e.g.,”The collaboration is very strong. There are sometimes intra referrals from TM units to orthodox and vice versa. Clients go to Out Patients Department, then to TM unit, we check vital statistics, then clients would be examined and recommended to do some laboratory test when necessary. We ensure constancy for the sake of report”—TM practitioner) to ‘not satisfied with the system’ (e.g., “We have not admitted any client who patronise TM and orthodox medicine. I don’t consider it as integration, because we are not working jointly with them”—orthodox medicine practitioner) [22].

3.3.5. Acceptance as a Measure of an Effective Integrated Health System in Africa

Acceptance was closely linked to the satisfaction of participants. While satisfaction evaluated the fulfilment that people derived from the integrated system, acceptance was deduced based on the value that participants placed on their role and the role of other stakeholders in the integration process. Eight of the reviewed pieces of literature indicated that the acceptance of integrated health systems in Africa was low among orthodox medicine practitioners [12,20,22,24,25,26,28,29]. For example, Falisse et al. [28] found that, although the majority of orthodox medicine practitioners in Burundi (91%) were aware of the integrated system, only 19% supported formal integration [28]. Related results were disclosed by a Ghanaian study, where orthodox medicine practitioners were highly unprepared to refer clients to TM practitioners [12]. Likewise, orthodox practitioners in South Africa frowned at the integration process because they (OMPs) perceived TM practice to be an obstacle to successful management of clients’ health [25]. Differing levels of acceptance were observed among TM practitioners. A Nigerian study [30] reported a high level (64%) of acceptance among TM practitioners at Mushin, Lagos, and the findings of Maluleka and Ngoepe [27] identified a contradictory report, as acceptance of the integrated system was low among TM practitioners in South Africa. This was because they (TM practitioners) experienced marginalization in the integrated system. One study found that perceived acceptance was reported to be high among both health practitioners in Ndola and Kabwe, in the Copper belt and Central provinces of Zambia. This was due to the fact that 77% of orthodox health providers and 97% of TM practitioners felt that there was a potential prospect for them to learn from each other in order to work effectively [31]. Overall, the practice of an integrated health system was popular among health service users. Two studies reported a high acceptance of an integrated system among service users in Ghana [12,17]. It also emerged that the practice of an integrated health system was highly favorable among scholars involved in TM research [23].

3.4. Assessment of the Methodological Quality

As indicated in Table 3, the included studies were of a good methodological quality and had QATSDD scores ranging from 57% to 86%. One study scored above 80%, and was thus classified as having an excellent methodological quality. Five studies scored above 70% and none of the studies were below 50%. The average methodological quality score of the included studies was 69%, which equates to an acceptable standard based on the criteria of the QATSDD assessment tool. Overall, the included studies provided detailed information about sampling, data collection methods, data analysis, and the strengths and limitations of the study.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of included studies using the quality assessment tool for studies with diverse designs (QATSDD).

4. Discussion

TM plays a significant role in health delivery, which has led to its integration into health systems of various African countries [33]. The rationale behind the integration of TM is to widen the scope of health delivery and improve health seeking behavior among populations [4]. Published research has shown that integration can only be successful if contextual factors, such as the health system architecture, socio-cultural characteristics, and views of stakeholders, are cautiously considered in the integration process [34]. Other important determinants include those directly related to health practitioners, service users, and the broader socio-political structure within which health systems operate [34]. Studies have also shown that the level of effectiveness of an integrated health system mostly relies on the nature of the relationship that exists between all stakeholders in the health sector [34,35].

This systematic review was therefore conducted to assess the effectiveness of integrated health systems in Africa. The measure of effectiveness was based on the awareness, usage, satisfaction, and acceptance of integrated systems. Reviewed articles reported that integrated health systems in Africa were ineffective. Knowledge about the existence of integrated systems was low in most countries and health service users favored the integration of TM into formal health systems. This result is mirrored in the works of Ben-Arye, Karkabi [36] and Jong, van de Vijver [37], where service users agreed that orthodox practitioners should guide clients to choose appropriate TM and refer them to qualified and experienced TM practitioners when the need arises. However, the review identified that the majority of users were uninformed about the official practice of TM in health centers, accounting for the low usage of integrated systems in Africa. Ignorance of service users was attributed to the absence of explicit protocols/documents clearly describing the concept of integration, as well as sensitizing the people about the integration process [22]. However, whilst health professionals, particularly orthodox medicine practitioners, were conversant with the practice of integrated health, their disposition towards the system was poor [28]. Sewitch, Cepoiu [38] confirmed the finding that doctors have an unfavorable attitude towards TM prescription and the referral of clients to TM practitioners. Shallow knowledge about the practice of integrated systems in Africa might be a factor contributing to the undesirably low patronage integrated health care.

The review established that the patronage of integrated health systems was unimpressive due to ineffective communication as a result of a non-functional referral system, the absence of an official document to promote the integrated system, the non-inclusion of TM products and services in national health cover, and skewed power relations within the integrated system [12,22,23,27,28,30]. The unsuccessful collaboration between the two health systems affected the quality of services offered by the consolidated health delivery unit. Therefore, the performance of integrated systems was reported to be unsatisfactory because health practitioners and service users such as stakeholders expressed dissatisfaction with the state of health systems in Africa.

Satisfaction is said to be achieved when health practitioners, together with service users/clients, derive fulfilment in practicing and accessing health services [39]. Most health systems in Africa have not achieved this goal. The review indicated low satisfaction among stakeholders. The unsatisfactory state of health systems in Africa mainly stems from inadequately trained TM practitioners, the slow rate of progress of the integration process, and incompetent measures aimed at eliminating charlatan practitioners [23,28]. Conversely, Agyei-Baffour, Kudolo [17] reported a rise in the use of TM among service users/clients because of moderate satisfaction derived from the integrated system. Orthodox medicine practitioners were not satisfied with the integration of TM into formal health systems because they deemed TM practice to be an obstacle to achieving a healthy population [25]. The absence of a common professional language between the two practitioners further deepened the displeasing state of integrated systems. This discovery is closely linked to the findings of Hollenberg [40] in Canada, where differences in terminologies created communication barriers between orthodox and TM practitioners and hindered professional collaboration in integrative health care facilities. This notwithstanding, TM practitioners were somewhat pleased with the system and acknowledged that there was hope for better integration of the two health entities. The review further assessed the acceptance of the practice of integrated systems.

Acceptance of the practice of integration was low among health practitioners, particularly orthodox health care providers, but high among health service users. This was mirrored in the findings of Falisse, Masino [28], as a relatively low percentage (19%) of orthodox practitioners supported formal integration, while a significant percentage (93%) of clients preferred integration. Likewise, the results of Maluleka and Ngoepe [27] identified that acceptance within the system was low among TM practitioners due to feelings of ostracization. The feeling of exclusion expressed by TM practitioners was a product of a sense of superiority by orthodox providers in the integration process, as well as exclusion of TM in the educational curriculum. Taken together, this review has unraveled key factors responsible for the non-functionality of health systems in Africa. Clearly, for health systems to be effective, more than mere lip service to policy formulations is required, and such policies should include other extraneous factors or interventions. Good health system research is needed to identify specific factors which impede the effective integration of TM into health systems. Future studies should focus on analysing the perceptions and experiences of stakeholders in relation to the integration process within a wider socio-political context.

Strengths and Limitations

This review relied upon reported experiences from participants to highlight the state and effectiveness of integrated health systems in Africa. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first article to assess the effectiveness of integrated health systems and factors impeding the integration process in Africa. However, the included studies were not evenly distributed as a majority of the studies were from Ghana [12,17,22,23,24]. The exclusion of grey literature and non-English articles created possible grounds for oversight. Furthermore, the QATSDD appraisal tool largely depends on reviewers’ knowledge. Therefore, there is a potential for bias [21]. There is also the possibility of misclassification and recall biases, since participants had to recollect their experiences with the integrated health system.

5. Conclusions

In Africa, the main step taken by countries to integrate TM into formal health systems is policy formulation and the creation of TM practice councils. Some countries have managed to establish institutions responsible for assessing the efficacy of TM and introduced TM practice into the tertiary educational system. Existing health policies are not working, so the integration of TM has not been successful. It is critical to uncover the bottlenecks in the health systems by exploring the perceptions and experiences of stakeholders, in order to offer solutions for better integration of the two health systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/56/6/271/s1, Table S1: Search Strategy for effectiveness of integrated health systems.

Author Contributions

Writing—Original draft preparation, I.G.A. writing—Review and editing, I.G.A., B.S.M.-A., A.E.O.M.-A., and T.I.E. All authors approved it for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Faith Alele for help with database searches.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Proceedings of the Promotion and Development of Traditional Medicine: Report of a WHO Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 28 November–2 December 1977; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Proceedings of the WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002–2005, Geneva, Switzerland, 28–31 January 2002; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Oreagba, I.; Oshikoya, K.A.; Amachree, M. Herbal medicine use among urban residents in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlberg, B.M. Integrated Health Care Systems and Indigenous Medicine: Reflections from the Sub-Sahara African Region. Front. Sociol. 2017, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krah, E.; De Kruijf, J.; Ragno, L. Integrating Traditional Healers into the Health Care System: Challenges and Opportunities in Rural Northern Ghana. J. Community Health 2017, 43, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, B.T.; Hatcher, J. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Pakistan: Prospects and Limitations. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2005, 2, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Ma, Y.; Drisko, J.; Chen, Q. Antitumor Activities of Rauwolfia vomitoria Extract and Potentiation of Carboplatin Effects Against Ovarian Cancer. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2013, 75, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.M.; Rousseau, M.E.; Robinson, E.H. Therapeutic use of selected herbs. Holist. Nurs. Pr. 2000, 14, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto, J.B. Efficacy, safety, quality control, marketing and regulatory guidelines for herbal medicines (phytotherapeutic agents). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2000, 33, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, L.G. Integration of Traditional Medicine into health systems in the African Region—The journey so far. Afr. Health Monit. 2003, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Freedman, L.P. Assessing health system performance in developing countries: A review of the literature. Health Policy 2008, 85, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyasi, R.M.; Poku, A.A.; Boateng, S.; Amoah, P.A.; Mumin, A.A.; Obodai, J.; Agyemang-Duah, W. Integration for coexistence? Implementation of intercultural health care policy in Ghana from the perspective of service users and providers. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 15, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keji, C.; Hao, X. The integration of traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine. Eur. Rev. 2003, 11, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, B.; Warude, D.; Pushpangadan, P.; Bhatt, N. Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Comparative Overview. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2005, 2, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. India’s government promotes traditional healing practices. Lancet 2000, 355, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconi, E.; Owoahene-Acheampong, S. Recognition and Integration of Traditional Medicine in Ghana A Perspective. Res. Rev. Inst. Afr. Stud. 2011, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei-Baffour, P.; Kudolo, A.; Quansah, D.; Boateng, D. Integrating herbal medicine into mainstream healthcare in Ghana: Clients’ acceptability, perceptions and disclosure of use. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuide, G.E. Regulation of herbal medicines in Nigeria: The role of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC). Adv. Phytomed. 2002, 1, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiba, S. Are biomedicine health practitioners ready to collaborate with traditional health practitioners in HIV & AIDS care in Tutume sub district of Botswana. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2010, 7, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sirriyeh, R.; Lawton, R.; Gardner, P.; Armitage, G. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: The development and evaluation of a new tool. J. Eval. Clin. Pr. 2011, 18, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, M.A.; Danso-Appiah, T.; Turkson, B.K.; Tersbøl, B.P. Integrating biomedical and herbal medicine in Ghana—experiences from the Kumasi South Hospital: A qualitative study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, B.; Amponsah, I.K.; Poudyal, A.; Mensah, M.L.K. Identifying strengths and weaknesses of the integration of biomedical and herbal medicine units in Ghana using the WHO Health Systems Framework: A qualitative study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahenkan, A.; Opoku-Mensah Abrampa, F.; Boon, K.E. Integrating traditional and orthodox medical practices in health care delivery in developing countries: Lessons from Ghana. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2019, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Hall, V.; Petersen, I.; Bhana, A.; Mjadu, S.; Hosegood, V.; Flisher, A.J. MHaPP Research Programme Consortium Collaboration Between Traditional Practitioners and Primary Health Care Staff in South Africa: Developing a Workable Partnership for Community Mental Health Services. Transcult. Psychiatry 2010, 47, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemutandani, S.M.; Hendricks, S.J.; Mulaudzi, M.F. Perceptions and experiences of allopathic health practitioners on collaboration with traditional health practitioners in post-apartheid South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2016, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maluleka, J.; Ngoepe, M. Integrating traditional medical knowledge into mainstream healthcare in Limpopo Province. Inf. Dev. 2018, 35, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falisse, J.-B.; Masino, S.; Ngenzebuhoro, R. Indigenous medicine and biomedical health care in fragile settings: Insights from Burundi. Health Policy Plan 2018, 33, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbor, A.M.; Naidoo, S. Knowledge and practice of traditional healers in oral health in the Bui Division, Cameroon. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awodele, O.; Agbaje, E.; Ogunkeye, F.; Kolapo, A.; Awodele, D. Towards integrating traditional medicine (TM) into National Health Care Scheme (NHCS): Assessment of TM practitioners’ disposition in Lagos, Nigeria. J. Herb. Med. 2011, 1, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboru, B.B.; Falkenberg, T.; Ndubani, P.; Höjer, B.; Vongo, R.; Brugha, R.; Faxelid, E. Can biomedical and traditional health care providers work together? Zambian practitioners’ experiences and attitudes towards collaboration in relation to STIs and HIV/AIDS care: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Resour. Health 2006, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wikimedia Commons. Blank Map of Africa. File Blank Map-Africa.svg. 2019. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/66/Blank_Map-Africa.svg (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Antwi-Baffour, S.S.; Bello, A.I.; Adjei, D.N.; Mahmood, S.A.; Ayeh-Kumi, P.F. The Place of Traditional Medicine in the African Society: The Science, Acceptance and Support. Am. J. Health Res. 2014, 2, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.L.; Canaway, R. Integrating Traditional and Complementary Medicine with National Healthcare Systems for Universal Health Coverage in Asia and the Western Pacific. Health Syst. Reform 2019, 5, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Car, L.T.; Brusamento, S.; Elmoniry, H.; Van Velthoven, M.H.; Pape, U.J.; Welch, V.; Tugwell, P.; Majeed, A.; Rudan, I.; Car, J.; et al. The Uptake of Integrated Perinatal Prevention of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission Programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arye, E.; Karkabi, K.; Karkabi, S.; Keshet, Y.; Haddad, M.; Frenkel, M. Attitudes of Arab and Jewish patients toward integration of complementary medicine in primary care clinics in Israel: A cross-cultural study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Vijver, L.M.J.; Busch, M.; Fritsma, J.; Seldenrijk, R. Integration of complementary and alternative medicine in primary care: What do patients want? Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 89, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewitch, M.; Cepoiu-Martin, M.; Rigillo, N.; Sproule, D. A Literature Review of Health Care Professional Attitudes Toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Complement. Health Pr. Rev. 2008, 13, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.; Cook, E.F.; Puopolo, A.L.; Burstin, H.R.; Cleary, P.D.; Brennan, T.A. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenberg, D. Uncharted ground: Patterns of professional interaction among complementary/alternative and biomedical practitioners in integrative health care settings. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).