The Trends of Complicated Acute Colonic Diverticulitis—A Systematic Review of the National Administrative Databases

Abstract

1. Introduction

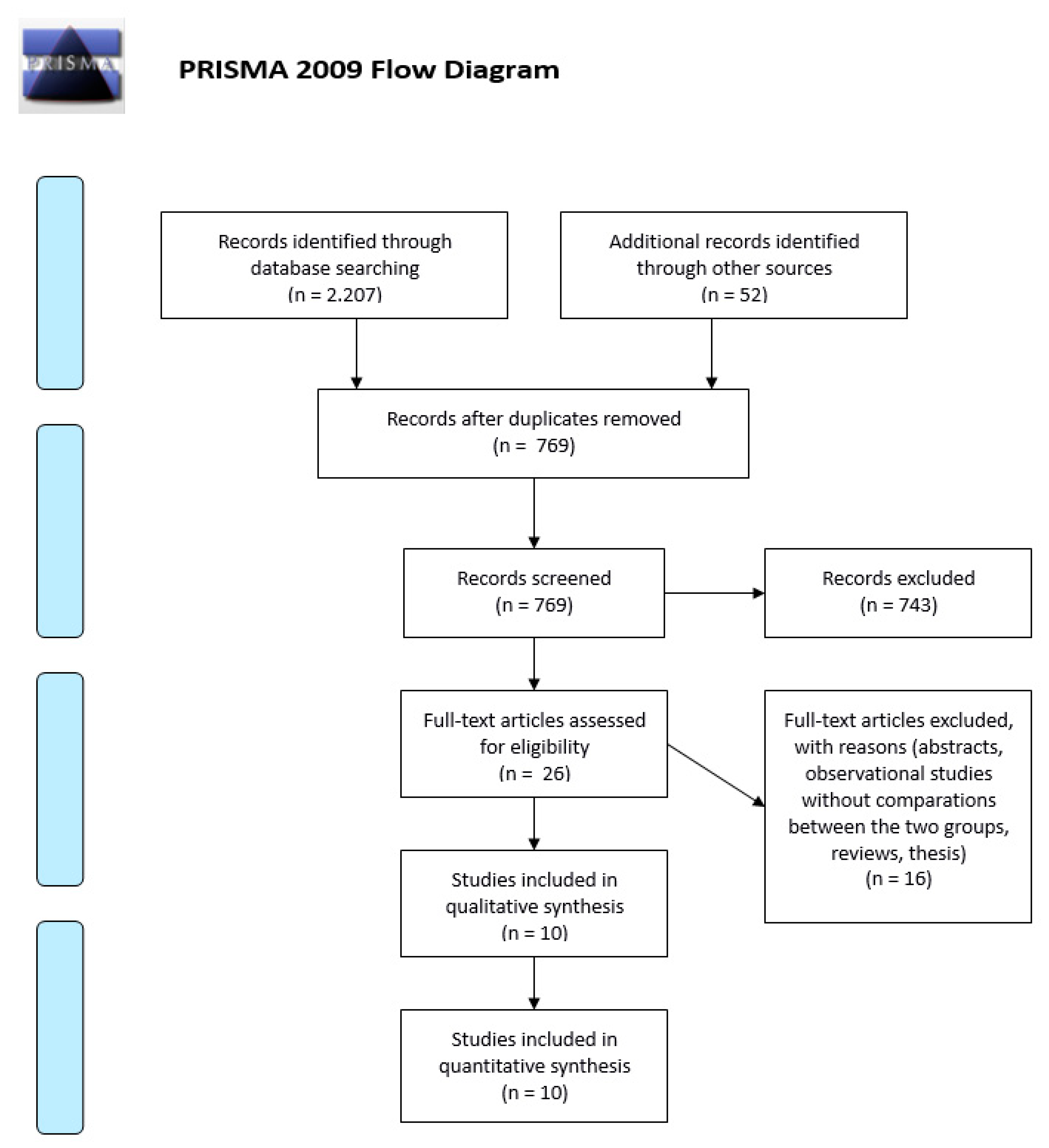

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author and Year of Publication | Reason for the Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Cammarota 2018 | There is overlapping with Amato 2019 |

| Lee 2018 | The authors compared the BMI, computed tomographic estimations of abdominal fat content, age, and sex |

| Dean 2018 | The authors identified only patients ≤50 with a diagnosis of diverticulitis in the NSQIP database |

| Cirocchi 2018 | The authors performed an anaòysis of surgical strategies in elderly patients |

| Mennini 2017 | The authors reported an economic analysis of diverticular disease |

| Tan 2016 | The authors performed an analysis of the predictors of acute diverticulitis severity |

| Jamal Talabani 2016 | The authors performed an evaluation for risk factors for admission for acute colonic diverticulitis |

| Bharucha 2015 | The authors performed a population-based analysis of acute diverticulitis |

| Schneider 2015 | The authors performed an analysis of emergency department presentation, admission, and surgical intervention for colonic diverticulitis in the United States, but they do not report any data about the complicated diverticulitis |

| Jamal Talabani 2014 | The authors performed a hospital analysis of patients with acute diverticulitis |

| Kim 2012 | The authors reported an analysis of the clinical factors for predicting severe diverticulitis in Korea |

| Sorser 2009 | The authors performed an analysis of the association between obesity and complicated diverticular disease |

| Andeweg 2008 | The authors evaluated the incidence and risk factors of recurrence after surgery for acute diverticulitis |

| Papagrigoriadis 2004 | The authors performed an analysis about clinical and cost analysis of inpatient and outpatient investigations, treatment and hospitalization |

| Kang 2003 | The authors do not report any data about the complicated diverticular disease |

| McConnell | The authors performed a hospital analysis of patients with acute diverticulitis |

References

- Sopeña, F.; Lanas, A. Management of colonic diverticular disease with poorly absorbed antibiotics and other therapies. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2011, 4, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebbane, M.; Dumont, R.; Jreige, R.; Eledjam, J.J. Epidemiology of acute abdominal pain in adults in the emergency department setting. In CT of the Acute Abdomen; Taourel, P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhut, A.; Veyrie, N. Complicated diverticular disease: The changing paradigm for treatment. Revista do Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões 2012, 39, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binda, G.A.; Mataloni, F.; Bruzzone, M.; Carabotti, M.; Cirocchi, R.; Nascimbeni, R.; Gambassi, G.; Amato, A.; Vettoretto, N.; Pinnarelli, L.; et al. Trends in hospital admission for acute diverticulitis in Italy from 2008 to 2015. Tech. Coloproctol. 2018, 22, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzioni, D.A.; Mack, T.M.; Beart, R.W.; Kaiser, A.M. Diverticulitis in the United States: 1998–2005: Changing patterns of disease and treatment. Ann. Surg. 2009, 249, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, L.J.; DeFrances, C.J.; Hall, M.J. National hospital discharge survey: 2004 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat Ser. 13 2006, 162, 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.R.; Harvey, I.M.; Stebbings, W.S.L.; Hart, A.R. Incidence of perforated diverticulitis and risk factors for death in a UK population. Br. J. Surg. 2008, 95, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, R.; Baxter, N.N.; Read, T.E.; Marcello, P.W.; Hall, J.; Roberts, P.L. Is the decline in the surgical treatment for diverticulitis associated with an increase in complicated diverticulitis? Dis. Colon Rectum 2009, 52, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoomi, H.; Buchberg, B.S.; Magno, C.; Mills, S.D.; Stamos, M.J. Trends in diverticulitis management in the United States from 2002 to 2007. Arch. Surg. 2011, 146, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamant, M.J.; Coward, S.; Buie, W.D.; MacLean, A.; Dixon, E.; Ball, C.G.; Schaffer, S.; Kaplan, G.G. Hospital volume and other risk factors for in-hospital mortality among diverticulitis patients: A nationwide analysis. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 29, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Parina, R.P.; Faiz, O.; Chang, D.C.; Talamini, M.A. Long-term outcomes after initial presentation of diverticulitis. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.K.Y.; Tomlin, A.M.; Hayes, I.P.; Skandarajah, A.R. Operative intervention rates for acute diverticulitis: A multicentre state-wide study. ANZ J. Surg. 2015, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamm, R.; Mathews, S.N.; Yang, J.; Kang, L.; Telem, D.; Pryor, A.D.; Talamini, M.; Genua, J. 20-year trends in the management of diverticulitis across New York state: An analysis of 265,724 patients. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017, 21, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.K.Y.; Skandarajah, A.R.; Higgins, R.D.; Faiz, O.D.; Hayes, I.P. International variation in emergency operation rates for acute diverticulitis: Insights into healthcare value. World J. Surg. 2017, 41, 2121–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hupfeld, L.; Pommergaard, H.C.; Burcharth, J.; Rosenberg, J. Emergency admissions for complicated colonic diverticulitis are increasing: A nationwide register-based cohort study. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2018, 33, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, A.; Nascimbeni, R.; Annibale, B.; Cirocchi, R.; Carabotti, M.; Gambassi, G.; Cuomo, R.; Binda, G.A. Complicated diverticulitis in Italy: Trends in patterns of disease and treatment. Tech. Colorectal Surg. 2018, 22, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota, S.; Cargiolli, M.; Andreozzi, P.; Toraldo, B.; Citarella, A.; Flacco, M.E.; Binda, G.A.; Annibale, B.; Manzoli, L.; Cuomo, R. Increasing trend in admission rates andcosts for acute diverticulitis during 2005–2015: Real-life data from the Abruzzo Region. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1756284818791502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Setty, P.T.; Parthasarathy, G.; Bailey, K.R.; Wood-Wentz, C.M.; Fletcher, J.G. Aging, obesity, and the incidence of diverticulitis: A population-based study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1256–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Kessler, H.; Gorgun, E. Surgical outcomes for diverticulitis in young patients: Results from the NSQIP database. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 4953–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi, R.; Nascimbeni, R.; Binda, G.A.; Vettoretto, N.; Cuomo, R.; Gambassi, G.; Amato, A.; Annibale, B. Surgical treatment of acute complicated diverticulitis in the elderly. Minerva. Chir. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennini, F.S.; Sciattella, P.; Marcellusi, A.; Toraldo, B.; Koch, M. Economic burden of diverticular disease: An observational analysis based on real world data from an Italian region. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017, 49, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.P.; Barazanchi, A.W.; Singh, P.P.; Hill, A.G.; Maccormick, A.D. Predictors of acute diverticulitis severity: A systematic review. Int. J. Surg. 2016, 26, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal Talabani, A.; Lydersen, S.; Ness-Jensen, E.; Endreseth, B.H.; Edna, T.H. Risk factors of admission for acute colonic diverticulitis in a population-based cohort study: The North Trondelag Health Study, Norway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 10663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharucha, A.E.; Parthasarathy, G.; Ditah, I.; Fletcher, J.G.; Ewelukwa, O.; Pendlimari, R.; Yawn, B.P.; Melton, L.J.; Schleck, C.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Temporal trends in the incidence and natural history of diverticulitis: A population-based study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal Talabani, A.; Lydersen, S.; Endreseth, B.H.; Edna, T.H. Major increase inadmission-and incidence rates of acute colonic diverticulitis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2014, 29, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Oh, T.H.; Seo, J.Y.; Jeon, T.J.; Seo, D.D.; Shin, W.C.; Choi, W.C.; Jeong, M.J. The clinical factors for predicting severe diverticulitis in Korea: A comparison with Western countries. Gut Liver 2012, 6, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorser, S.A.; Hazan, T.B.; Piper, M.; Maas, L.C. Obesity and complicated diverticular disease: Is there an association? South. Med. J. 2009, 102, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andeweg, C.; Peters, J.; Bleichrodt, R.; van Goor, H. Incidence and risk factors of recurrence after surgery for pathology-proven diverticular disease. World J. Surg. 2008, 32, 1501–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagrigoriadis, S.; Debrah, S.; Koreli, A.; Husain, A. Impact of diverticular disease on hospital costs and activity. Colorectal Dis. 2004, 6, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y.; Hoare, J.; Tinto, A.; Subramanian, S.; Ellis, C.; Majeed, A.; Melville, D.; Maxwell, J.D. Diverticular disease of the colon-on the rise: A study of hospital admissions in England between 1989/1990 and 1999/2000. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 17, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, E.J.; Tessier, D.J.; Wolff, B.G. Population-based incidence of complicated diverticular disease of the sigmoid colon based on gender and age. Dis. Colon Rectum 2003, 46, 1110–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandler, R.S.; Everhart, J.E.; Donowitz, M.; Adams, E.; Cronin, K.; Goodman, C.; Gemmen, E.; Shah, S.; Avdic, A.; Rubin, R. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 1500–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheat, C.L.; Strate, L.L. Trends in hospitalization for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding in the United States from 2000 to 2010. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamichi, N.; Shimamoto, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Kakimoto, H.; Matsuda, R.; Kataoka, Y.; Saito, I.; Tsuji, Y.; Yakabi, S.; et al. Trend and risk factors of diverticulosis in Japan: Age, gender, and lifestyle/metabolic-related factors may cooperatively affect on the colorectal diverticula formation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 0123688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, F.; Moore, E.; Burlew, C.; Coimbra, R.; McIntryre, R.C.; Davis, J.W.; Sperry, J.; Biffl, W.L. Western Association critical decisions in trauma: Management of complicated diverticulitis. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 73, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarteli, M.; Catena, F.; Ansaloni, L.; Coccolini, F.; Griffits, E.A.; Abu-Zidan, F.M.; Di Saverio, S.; Ulrich, J.; Kluger, Y.; Ben-Ishay, O.; et al. WSES guidelines for the management of acute left sided colonic diverticulitis in the emergency setting. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2016, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klarenbeek, B.R.; de Korte, N.; Van der Peet, D.L.; Cuesta, M.A. Review of current classifications for diverticular disease and a translation into clinical practice. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2012, 27, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.C.; Bundgaard, L.; Elbrønd, H.; Laurberg, S.; Walker, L.R.; Støvring, J. Danish national guidelines for treatment of diverticular disease. Dan. Med. J. 2012, 59, C4453. [Google Scholar]

- Wasvary, H.; Turfah, F.; Kadro, O.; Beauregard, W. Same hospitalization resection for acute diverticulitis. Am. Surg. 1999, 65, 632–635. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, L.; Sauerland, S.; Neugebauer, E. Diagnosis and treatment of diverticular disease: Results of a consensus development conference. The Scientific Committee of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery. Surg. Endosc. 1999, 13, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocchi, R.; Randolph, J.; Binda, G.; Gioia, S.; Henry, B.; Tomaszewski, K.; Allegritti, M.; Arezzo, A.; Marzaioli, R.; Ruscelli, P. Is the outpatient management of acute diverticulitis safe and effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech. Coloproctol. 2019, 23, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartelli, M.; Moore, F.; Ansaloni, L.; Di Saverio, S.; Coccolini, F.; Griffiths, E.; Coimbra, R.; Agresta, F.; Sakakushev, B.; Ordoñez, C.A.; et al. A proposal for a CT driven classification of the left colon acute diverticulitis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2015, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Years of the Research | Nation | N. of Patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morris [8] 2008 | 1995–2000 | The counties of Norfolk and Suffolk, UK | 202 (only perforated diverticulitis) | ||

| Ricciardi [9] 2009 | 1991–2005 | USA | 685,390 | ||

| Masoomi [10] 2011 | 2002–2007 | USA | 1,073,397 | ||

| Diamant [11] 2015 | 1993–2008 | United States | 822,865 | ||

| Rose [12] 2015 | 1995–2009 | USA | 210,268 | ||

| Hong [13] 2015 | 2009–2013 | Australia | 2829 | ||

| Lamm [14] 2016 | 1995–2014 | USA | 265,724 | ||

| Hong [15] 2017 | 2008–2014 | USA, England, Australia | USA | England | Australia |

| 5332 | 6647 | 3171 | |||

| Hupfeld [16] 2018 | 2000–2012 | Denmark | 44,160 | ||

| Amato [17] 2019 | 2008–2015 | Italy | 41,622 | ||

| Study | General Codes for AD | Codes for Complicated AD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morris [8] 2008 | NR | ICD-10: | ||

| ||||

| Ricciardi [9] 2009 | ICD-9-CM: 562.11 and 562.13 (diverticulitis with and without mention of hemorrhage) | ICD-9-CM | ||

| ||||

| Masoomi [10] 2011 | ICD-9-CM: 562.11 and 562.13 (diverticulitis with and without mention of hemorrhage) | NR | ||

| Diamant [11] 2015 | ICD-9-CM:562.11 and 562.13 (diverticulitis with and without mention of hemorrhage) | ICD-9-CM: | ||

| ||||

| Rose [12] 2015 | ICD-9-CM: 562.11 and 562.13 (diverticulitis with and without mention of hemorrhage) | NR | ||

| Hong [13] 2015 | NR | ICD-10-AM: | ||

| ||||

| Lamm [14] 2016 | ICD-9-CM: 562.11 and 562.13 (diverticulitis with and without mention of hemorrhage) | NR | ||

| Hong [15] 2017 | NR | USA | England ICD-10 | Australia ICD-10-AM |

| K57.2 | K57.2 | |||

| Hupfeld [16] 2018 | ICD-10 uncomplicated AD: | ICD-10: | ||

|

| |||

| Amato [17] 2019 | ICD-9-CM: 562.11 and 562.13 (diverticulitis with and without mention of hemorrhage) | ICD-9-CM: | ||

| ||||

| Study | Number or Percentage | Total Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morrison [8] 2008 (in 5 years) | 202 | NR | ||||

| Ricciardi [9] 2009 (in 14 years) | NR | 685,390 | ||||

| Masoomi [10] 2011 (in 5 years) | 840,157 | 1,073,397 | ||||

| Diamant [11] 2015 (in 15 years) | 79.4% | 822,865 | ||||

| Rose [12] 2015 (in 14 years) | 61,064 | 210,268 | ||||

| Hong [13] 2015 (in 4 years) | 724 | 2829 | ||||

| Lamm [14] 2016 (in 19 years) | NR | 265,724 | ||||

| Hong [15] 2017 (in 6 years) | USA | England | Australia | USA | England | Australia |

| 1729 | 1677 | 771 | 5332 | 6647 | 3171 | |

| Hupfeld [16] 2018 | 485 patients (12.98%) (in 2000) vs. 692 patients (14.83%) (in 2012) | 44,160 | ||||

| Amato [17] 2019 | 41.62% | 174,436 | ||||

| Study | N of Peritonitis | N of Hospitalizations for Complicated AD | % Hospitalizations for Complicated AD | N of Admissions for AD | % Hospitalizations for AD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morris [8] 2008 | 96 * (III) | 202 | 47.5% | NR | NR | ||||

| 38 † (IV) | 202 | 18.8% | NR | NR | |||||

| Ricciardi [9] 2009 | 504 ‡ | NR | NR | 685,390 | 1.6% | ||||

| 910 § | NR | NR | 1.5% | ||||||

| Masoomi [10] 2011 | NR | 840,157 | NR | 1,073,397 | NR | ||||

| Diamant [11] 2015 | NR | NR | NR | 822,865 | 1.6% ‖ | ||||

| Rose [12] 2015 | 7044 | 61,064 | 11.5% | 210.268 | 3.4% | ||||

| Hong [13] 2015 | NR | 724 | NR | 2,829 | NR | ||||

| Lamm [14] 2016 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Hong [15] 2017 | NR | USA | England | Australia | NR | USA | England | Australia | NR |

| 1729 | 1677 | 771 | 5332 | 6647 | 3171 | ||||

| Hupfeld [16] 2018 | NR | NR | NR | 44,160 | NR | ||||

| Amato [17] 2019 | 17.811 | 41,622 | 42.79% | 174,436 | 10.21% | ||||

| Study | N of Abscess | N of Hospitalizations for Complicated AD | % Hospitalizations for Complicated AD | N of Admissions for AD | % Hospitalizations for AD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morris [8] 2008 | 9 * | 202 | 4.5% | NR | NR | ||||

| 59 † | 202 | 29.2% | NR | NR | |||||

| Ricciardi [9] 2009 | 1855 ‡ | NR | NR | 685,390 | 5.9% | ||||

| 5837 § | NR | NR | 9.6% | ||||||

| Masoom [10] 2011 | NR | 840,157 | NR | 1,073,397 | NR | ||||

| Diamant [11] 2015 | NR | NR | NR | 822,865 | 8.1% ‖ | ||||

| Rose [12] 2015 | 16,613 | 61,064 | 27.2% | 210,268 | 7.9% | ||||

| Hong [13] 2015 | NR | 724 | NR | 2829 | NR | ||||

| Lamm [14] 2016 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Hong [15] 2017 | NR | USA | England | Australia | NR | USA | England | Australia | NR |

| 1729 | 1677 | 771 | 5332 | 6647 | 3171 | ||||

| Hupfeld [16] 2018 | NR | NR | NR | 44,160 | NR | ||||

| Amato [17] 2019 | 2143 | 41,622 | 5.15% | 174,436 | 1.23% | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cirocchi, R.; Popivanov, G.; Corsi, A.; Amato, A.; Nascimbeni, R.; Cuomo, R.; Annibale, B.; Konaktchieva, M.; Binda, G.A. The Trends of Complicated Acute Colonic Diverticulitis—A Systematic Review of the National Administrative Databases. Medicina 2019, 55, 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55110744

Cirocchi R, Popivanov G, Corsi A, Amato A, Nascimbeni R, Cuomo R, Annibale B, Konaktchieva M, Binda GA. The Trends of Complicated Acute Colonic Diverticulitis—A Systematic Review of the National Administrative Databases. Medicina. 2019; 55(11):744. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55110744

Chicago/Turabian StyleCirocchi, Roberto, Georgi Popivanov, Alessia Corsi, Antonio Amato, Riccardo Nascimbeni, Rosario Cuomo, Bruno Annibale, Marina Konaktchieva, and Gian Andrea Binda. 2019. "The Trends of Complicated Acute Colonic Diverticulitis—A Systematic Review of the National Administrative Databases" Medicina 55, no. 11: 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55110744

APA StyleCirocchi, R., Popivanov, G., Corsi, A., Amato, A., Nascimbeni, R., Cuomo, R., Annibale, B., Konaktchieva, M., & Binda, G. A. (2019). The Trends of Complicated Acute Colonic Diverticulitis—A Systematic Review of the National Administrative Databases. Medicina, 55(11), 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55110744