The Role of Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis Induced by Metals and Xenobiotics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Carcinogenesis and Oxidative Stress Associated with Selected Metals and Metalloids

2.1. Arsenic (As)

2.2. Chromium (Cr)

2.3. Nickel (Ni)

). An interplay of enhanced proliferation and up-regulation of p53 could constitute a strong selective pressure, favouring mutations, which may inactivate tumor suppressor genes (see text for details).

). An interplay of enhanced proliferation and up-regulation of p53 could constitute a strong selective pressure, favouring mutations, which may inactivate tumor suppressor genes (see text for details).

). An interplay of enhanced proliferation and up-regulation of p53 could constitute a strong selective pressure, favouring mutations, which may inactivate tumor suppressor genes (see text for details).

). An interplay of enhanced proliferation and up-regulation of p53 could constitute a strong selective pressure, favouring mutations, which may inactivate tumor suppressor genes (see text for details).

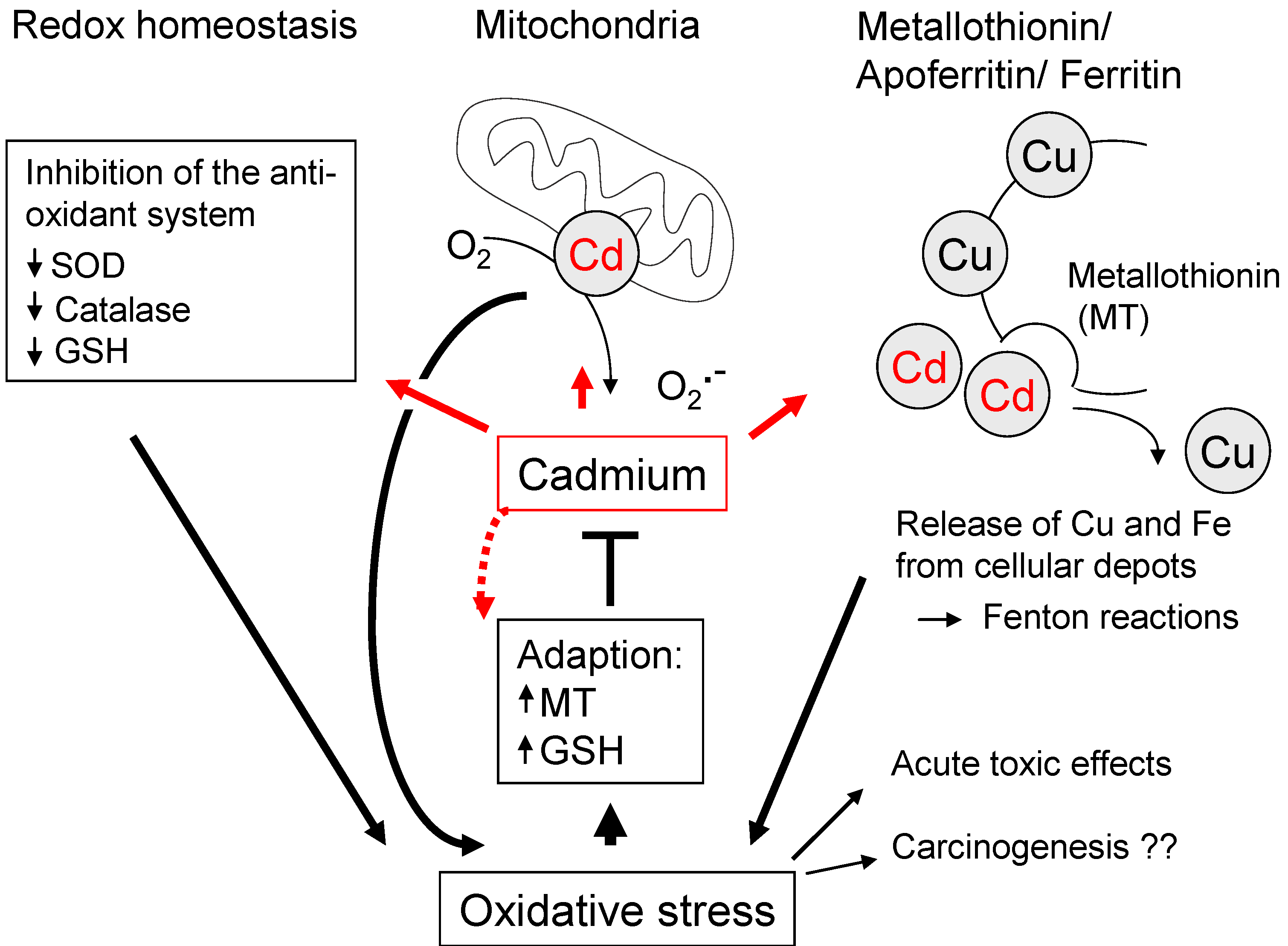

2.4. Cadmium (Cd)

3. Oxidative Stress Associated with Organic Compounds—Implications for Carcinogenesis

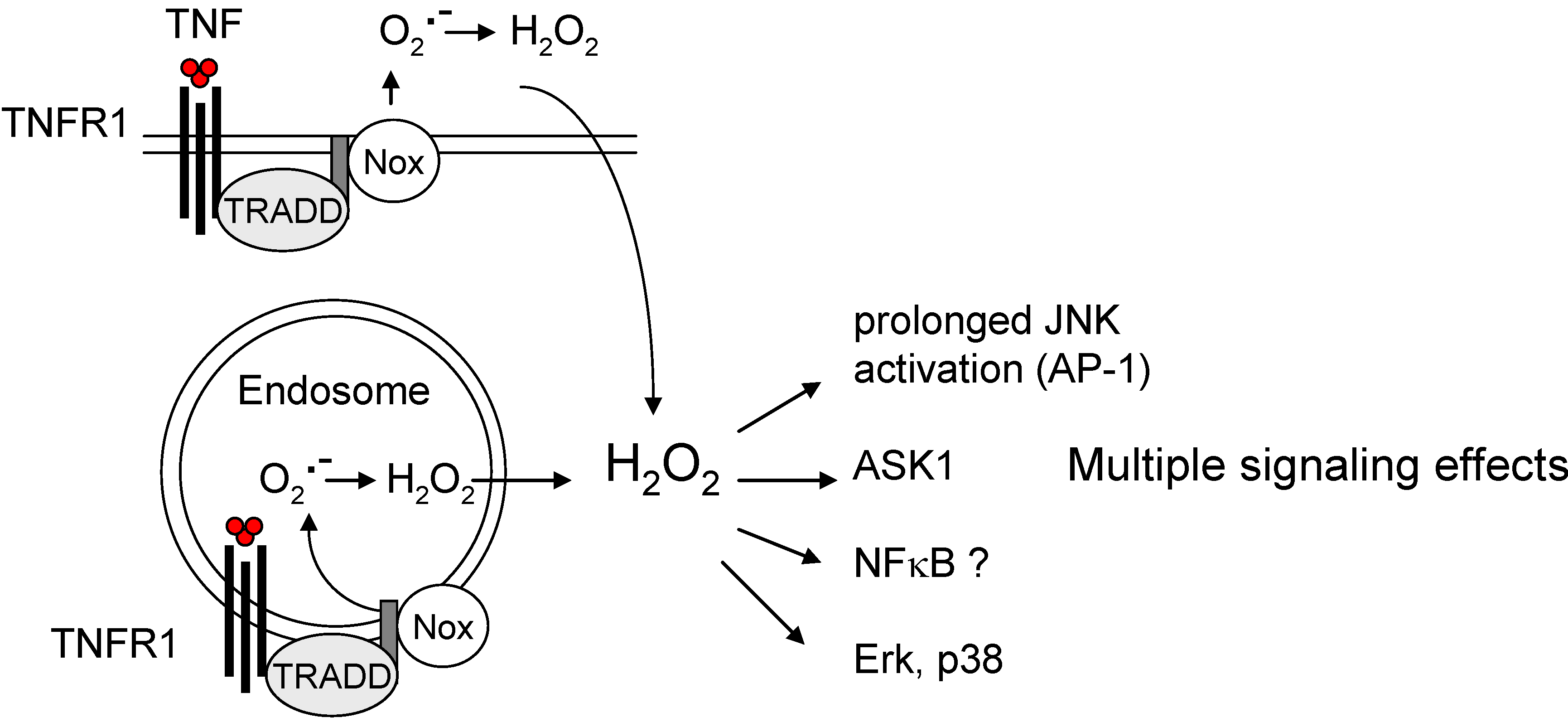

4. Endogenous ROS Signalling and Tumor Promotion

5. Conclusions and Outlook

References

- Cadenas, E.; Davies, K.J. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 29, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, S.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Novo, E.; Parola, M. Redox mechanisms in hepatic chronic wound healing and fibrogenesis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2008, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boveris, A.; Oshino, N.; Chance, B. The cellular production of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. J. 1972, 128, 617–630. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, J.K.; Mannaerts, G.P. Peroxisomal lipid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1994, 14, 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanders, R.J.; Ferdinandusse, S.; Brites, P.; Kemp, S. Peroxisomes, lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1801, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, M.; Fahimi, H.D. Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1763, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Rao, S.; Reddy, J.K. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, fatty acid oxidation, steatohepatitis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Curr. Mol. Med. 2003, 3, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilger, A.; Rudiger, H.W. 8-Hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine as a marker of oxidative DNA damage related to occupational and environmental exposur. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2006, 80, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyokuni, S. Role of iron in carcinogenesis: cancer as a ferrotoxic disease. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, M.C. Hepatic iron overload and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2009, 286, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeldandi, A.V.; Rao, M.S.; Reddy, J.K. Hydrogen peroxide generation in peroxisome proliferator-induced oncogenesis. Mutat. Res. 2000, 448, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.Y.; Pan, J.; Usuda, N.; Yeldandi, A.V.; Rao, M.S.; Reddy, J.K. Steatohepatitis, spontaneous peroxisome proliferation and liver tumors in mice lacking peroxisomal fatty acyl-CoA oxidase. Implications for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α natural ligand metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 15639–15645. [Google Scholar]

- Guyton, K.Z.; Chiu, W.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Jinot, J.; Scott, C.S.; Brown, R.C.; Caldwell, J.C. A reexamination of the PPARα activation mode of action as a basis for assessing human cancer risks of environmental contaminants. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Beyersmann, D.; Hartwig, A. Carcinogenic metal compounds: recent insights into molecular and cellular mechanisms. Arch. Toxicol. 2008, 82, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council, Arsenic in Drinking Water; Washington DC; National Academy Press, 1990; pp. 27–82.

- Ökotest (German magazine) 2009. Available online: http://www.öko-test.de/cgi/index.cgi?artnr=93759;bernr=04;co (accessed on 15 February 2010).

- Smith, A.H.; Goycolea, M.; Haque, R.; Biggs, M.L. Marked increase in bladder and lung cancer mortality in a region of Northern Chile due to arsenic in drinking water. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 147, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.M.; Kuo, T.L.; Hwang, Y.H.; Chen, C.J. Dose-response relation between arsenic concentration in well water and mortality from cancers and vascular diseases. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1989, 130, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Mass, M.J.; Tennant, A.; Roop, B.C.; Cullen, W.R.; Styblo, M.; Thomas, D.J.; Kligerman, A.D. Methylated trivalent arsenic species are genotoxic. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001, 14, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Shi, X.; Liu, K.J. Oxidative mechanism of arsenic toxicity and carcinogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004, 255, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Piatek, K.; Schwerdtle, T.; Hartwig, A.; Bal, W. Monomethylarsenous acid destroys a tetrathiolate zinc finger much more efficiently than inorganic arsenite: mechanistic considerations and consequences for DNA repair inhibition. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtle, T.; Walter, I.; Hartwig, A. Arsenite and its biomethylated metabolites interfere with the formation and repair of stable BPDE-induced DNA adducts in human cells and impair XPAzf and Fpg. DNA Repair 2003, 2, 1449–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waalkes, M.P.; Liu, J.; Ward, J.M.; Diwan, B.A. Animal models for arsenic carcinogenesis: inorganic arsenic is a transplacental carcinogen in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004, 198, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Diwan, B.A.; Barrett, J.C.; Waalkes, M.P. Chronic inorganic arsenic exposure induces hepatic global and individual gene hypomethylation: implications for arsenic hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Wakai, T.; Shirai, Y.; Hatakeyama, K.; Hirano, S. Chronic oral exposure to inorganic arsenate interferes with methylation status of p16INK4a and RASSF1A and induces lung cancer in A/J mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 91, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, S.; Dasgupta, U.B.; Guhamazumder, D.; Gupta, M.; Chaudhuri, U.; Lahiri, S.; Das, S.; Ghosh, N.; Chatterjee, D. DNA hypermethylation of promoter of gene p53 and p16 in arsenic-exposed people with and without malignancy. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 89, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.; Schoneveld, O.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Oxidative stress, DNA methylation and carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2008, 266, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, K.T.; Conolly, R. Arsenic-induced carcinogenesis-oxidative stress as a possible mode of action and future research needs for more biologically based risk assessment. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 23, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaya-Ruiz, A.; Barbier, O.; Ruiz-Ramos, R.; Cebrian, M.E. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and damage in human populations exposed to arsenic. Mutat. Res. 2009, 674, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Hudson, L.G.; Ding, W.; Wang, S.; Cooper, K.L.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, K.J. Arsenite causes DNA damage in keratinocytes via generation of hydroxyl radicals. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004, 17, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourahmad, J.; Rabiei, M.; Jokar, F.; O'Brien, P.J. A comparison of hepatocyte cytotoxic mechanisms for chromate and arsenite. Toxicology 2005, 206, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, K.; Hoshino, M.; Okamoto, M.; Sawamura, R.; Hasegawa, A.; Okada, S. Induction of DNA damage by dimethylarsine, a metabolite of inorganic arsenics, is for the major part likely due to its peroxyl radical. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 168, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jin, X.; Snow, E.T. Effect of arsenic on transcription factor AP-1 and NF-κB DNA binding activity and related gene expression. Toxicol. Lett. 2002, 133, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cai, J.F.; Chiu, J.F. Arsenic induces oxidative stress and activates stress gene expressions in cultured lung epithelial cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 87, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapahi, P.; Takahashi, T.; Natoli, G.; Adams, S.R.; Chen, Y.; Tsien, R.Y.; Karin, M. Inhibition of NF-κB activation by arsenite through reaction with a critical cysteine in the activation loop of IκB kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 36062–36066. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Chromium, nickel and welding, IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans; IARC: Lyon, France, 1990; Volume 49, pp. 49–256.

- De Flora, S.; Bagnasco, M.; Serra, D.; Zanacchi, P. Genotoxicity of chromium compounds. Mutat. Res. 1990, 238, 99–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Klein, C.B. Toxicity and carcinogenicity of chromium compounds in humans. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2006, 36, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, K.S. Oxidative DNA and protein damage in metal-induced toxicity and carcinogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 32, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, T.J.; Ceryak, S.; Patierno, S.R. Complexities of chromium carcinogenesis: role of cellular response, repair and recovery mechanisms. Mutat. Res. 2003, 533, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhitkovich, A. Importance of chromium-DNA adducts in mutagenicity and toxicity of chromium(VI). Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005, 18, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, E.T. A possible role for chromium(III) in genotoxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 1991, 92, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voitkun, V.; Zhitkovich, A.; Costa, M. Cr(III)-mediated crosslinks of glutathione or amino acids to the DNA phosphate backbone are mutagenic in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 2024–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, M.J.; Davies, M.J. Direct evidence for the hydroxyl radical-induced damage to nucleic acids by chromium(VI)-derived species: implications for chromium carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 1995, 16, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetterhahn, K.E.; Hamilton, J.W.; Aiyar, J.; Borges, K.M.; Floyd, R. Mechanism of chromium(VI) carcinogenesis. Reactive intermediates and effect on gene expression. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1989, 21, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Leonard, S.S.; Liu, K.J.; Zang, L.; Gannett, P.M.; Rojanasakul, Y.; Castranova, V.; Vallyathan, V. Cr(III)-mediated hydroxyl radical generation via Haber-Weiss cycle. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1998, 69, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhang, X.; Young, H.A.; Mao, Y.; Shi, X. Chromium(VI)-induced nuclear factor-κB activation in intact cells via free radical reactions. Carcinogenesis 1995, 16, 2401–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Nickel and its inorganic compounds. In The MAK Collection for Occupational Health and Safety, Part I: MAK Value Documentations; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; Volume 22, pp. 1–41.

- Dunnick, J.K.; Elwell, M.R.; Radovsky, A.E.; Benson, J.M.; Hahn, F.F.; Nikula, K.J.; Barr, E.B.; Hobbs, C.H. Comparative carcinogenic effects of nickel subsulfide, nickel oxide, or nickel sulfate hexahydrate chronic exposures in the lung. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 5251–5256. [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzak, K.S.; Hernandez, L. Enhancement of hydroxylation and deglycosylation of 2'-deoxyguanosine by carcinogenic nickel compounds. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 5964–5968. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, D.R.; Phillips, D.H. Oxidative DNA damage mediated by copper(II), iron(II) and nickel(II) fenton reactions: evidence for site-specific mechanisms in the formation of double-strand breaks, 8-hydroxy-deoxyguanosine and putative intrastrand cross-links. Mutat. Res. 1999, 424, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M'Bemba-Meka, P.; Lemieux, N.; Chakrabarti, S.K. Role of oxidative stress and intracellular calcium in nickel carbonate hydroxide-induced sister-chromatid exchange, and alterations in replication index and mitotic index in cultured human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Arch. Toxicol. 2007, 81, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salnikow, K.; Blagosklonny, M.V.; Ryan, H.; Johnson, R.; Costa, M. Carcinogenic nickel induces genes involved with hypoxic stress. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.W.; Broday, L.; Costa, M. Effects of nickel on DNA methyltransferase activity and genomic DNA methylation levels. Mutat. Res. 1998, 415, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, B.; Klafter, R.; Miller, M.S.; Mansur, C.; Mizesko, M.; Bai, X.; LaMontagne, K., Jr.; Arbiser, J.L. Reactive oxygen-induced carcinogenesis causes hypermethylation of p16Ink4a and activation of MAP kinase. Mol. Med. 2002, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyokuni, S. Molecular mechanisms of oxidative stress-induced carcinogenesis: from epidemiology to oxygenomics. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dally, H.; Hartwig, A. Induction and repair inhibition of oxidative DNA damage by nickel(II) and cadmium(II) in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis 1997, 18, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, A.; Mullenders, L.H.; Schlepegrell, R.; Kasten, U.; Beyersmann, D. Nickel(II) interferes with the incision step in nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 4045–4051. [Google Scholar]

- Broday, L.; Peng, W.; Kuo, M.H.; Salnikow, K.; Zoroddu, M.; Costa, M. Nickel compounds are novel inhibitors of histone H4 acetylation. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, D.; Salnikow, K. Molecular mechanisms of nickel carcinogenesis: gene silencing by nickel delivery to the nucleus and gene activation/inactivation by nickel-induced cell signaling. J. Environ. Monit. 2003, 5, 222–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Salnikow, K.; Sutherland, J.E.; Broday, L.; Peng, W.; Zhang, Q.; Kluz, T. The role of oxidative stress in nickel and chromate genotoxicity. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 234–235, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Davidson, T.L.; Chen, H.; Ke, Q.; Zhang, P.; Yan, Y.; Huang, C.; Kluz, T. Nickel carcinogenesis: epigenetics and hypoxia signaling. Mutat. Res. 2005, 592, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, M.; Kondo, K.; Yang, H.; Kim, W.; Valiando, J.; Ohh, M.; Salic, A.; Asara, J.M.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr. HIFα targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science 2001, 292, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L.; Wang, G.L. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992, 12, 5447–5454. [Google Scholar]

- Namiki, A.; Brogi, E.; Kearney, M.; Kim, E.A.; Wu, T.; Couffinhal, T.; Varticovski, L.; Isner, J.M. Hypoxia induces vascular endothelial growth factor in cultured human endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 31189–31195. [Google Scholar]

- Semenza, G.L. Involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in human cancer. Intern. Med. 2002, 41, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, P.; Salnikow, K. HIF-1: an oxygen and metal responsive transcription factor. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2004, 3, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salnikow, K.; Davidson, T.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.C.; Su, W.; Costa, M. The involvement of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-1-dependent pathway in nickel carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 3524–3530. [Google Scholar]

- Achison, M.; Hupp, T.R. Hypoxia attenuates the p53 response to cellular damage. Oncogene 2003, 22, 3431–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salnikow, K.; An, W.G.; Melillo, G.; Blagosklonny, M.V.; Costa, M. Nickel-induced transformation shifts the balance between HIF-1 and p53 transcription factors. Carcinogenesis 1999, 20, 1819–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V.; An, W.G.; Romanova, L.Y.; Trepel, J.; Fojo, T.; Neckers, L. p53 inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-stimulated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 11995–11998. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Cadmium in food: Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain. EFSA J. 2009, 980, 1–139.

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Cadmium and ist compounds (in the form of inhalable dusts/aerosols). In The MAK Collection for Occupational Health and Safety, Part I: MAK Value Documentations; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; Volume 22, pp. 119–146.

- Waalkes, M.P. Cadmium carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 2003, 533, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmuss, M.; Mullenders, L.H.; Hartwig, A. Interference by toxic metal compounds with isolated zinc finger DNA repair proteins. Toxicol. Lett. 2000, 112–113, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkowski, K.; Kasprzak, K.S. A novel assay of 8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine 5'-triphosphate pyrophospho-hydrolase (8-oxo-dGTPase) activity in cultured cells and its use for evaluation of cadmium(II) inhibition of this activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 3194–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaginis, C.; Gatzidou, E.; Theocharis, S. DNA repair systems as targets of cadmium toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006, 213, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisberg, M.; Joseph, P.; Hale, B.; Beyersmann, D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cadmium carcinogenesis. Toxicology 2003, 192, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.; Muchnok, T.K.; Klishis, M.L.; Roberts, J.R.; Antonini, J.M.; Whong, W.Z.; Ong, T. Cadmium-induced cell transformation and tumorigenesis are associated with transcriptional activation of c-fos, c-jun, and c-myc proto-oncogenes: role of cellular calcium and reactive oxygen species. Toxicol. Sci. 2001, 61, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jan, K.Y. DNA damage in arsenite- and cadmium-treated bovine aortic endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.A.; Lee, C.H.; Shukla, G.S.; Shukla, A.; Osier, M.; Eneman, J.D.; Chiu, J.F. Characterization of cadmium-induced apoptosis in rat lung epithelial cells: evidence for the participation of oxidant stress. Toxicology 1999, 133, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, D.; Ricard, A.C.; Tra, H.V.; Chevalier, G. Relation between lipid peroxidation and inflammation in the pulmonary toxicity of cadmium. Arch. Toxicol. 1994, 68, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.J.; Joshi, J.G. Ferritin. Binding of beryllium and other divalent metal ions. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 10873–10880. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, P.; Salacinski, H.J. Evidence that the reactions of cadmium in the presence of metallothionein can produce hydroxyl radicals. Arch. Toxicol. 1998, 72, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, J.; Leonard, S.S.; Rao, K.M. Cadmium inhibits the electron transfer chain and induces reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, E.; Calzaretti, G.; Sblano, C.; Landriscina, C. Molecular inhibitory mechanisms of antioxidant enzymes in rat liver and kidney by cadmium. Toxicology 2002, 179, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, D.; Shukla, G.S.; Agarwal, A.K. Glutathione depletion and oxidative damage in mitochondria following exposure to cadmium in rat liver and kidney. Toxicol. Lett. 1999, 106, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayama, F.; Yoshida, T.; Elwell, M.R.; Luster, M.I. Role of tumor necrosis factor-α in cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1995, 131, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qu, W.; Kadiiska, M.B. Role of oxidative stress in cadmium toxicity and carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 238, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somji, S.; Zhou, X.D.; Garrett, S.H.; Sens, M.A.; Sens, D.A. Urothelial cells malignantly transformed by exposure to cadmium (Cd(+2)) and arsenite (As(+3)) have increased resistance to Cd(+2) and As(+3)-induced cell death. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 94, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Waterland, R.A.; Dill, A.L.; Webber, M.M.; Waalkes, M.P. Tumor suppressor gene inactivation during cadmium-induced malignant transformation of human prostate cells correlates with overexpression of de novo DNA methyltransferase. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 1454–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, W.; Ke, H.; Pi, J.; Broderick, D.; French, J.E.; Webber, M.M.; Waalkes, M.P. Acquisition of apoptotic resistance in cadmium-transformed human prostate epithelial cells: Bcl-2 overexpression blocks the activation of JNK signal transduction pathway. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Z.A.; Vu, T.T.; Zaman, K. Oxidative stress as a mechanism of chronic cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity and renal toxicity and protection by antioxidants. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999, 154, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, C.D.; Liu, J.; Choudhuri, S. Metallothionein: an intracellular protein to protect against cadmium toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999, 39, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.E.; Luch, A. Reactive species: a cell damaging rout assisting to chemical carcinogens. Cancer Lett. 2008, 266, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luch, A. The Carcinogenic Effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lorentzen, R.J.; Lesko, S.A.; McDonald, K.; Ts'o, P.O. Toxicity of metabolic benzo[a]pyrene diones to cultured cells and the dependence upon molecular oxygen. Cancer Res. 1979, 39, 3194–3198. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Trush, M.A. Characterization of benzo[a]pyrene quinone-induced toxicity to primary cultured bone marrow stromal cells from DBA/2 mice: potential role of mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1995, 130, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick, A.D.; Davis, J.W.; Liu, K.J.; Hudson, L.G.; Shi, H.; Monske, M.L.; Burchiel, S.W. Benzo[a]pyrene quinones increase cell proliferation, generate reactive oxygen species, and transactivate the epidermal growth factor receptor in breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 7825–7833. [Google Scholar]

- Burchiel, S.W.; Thompson, T.A.; Lauer, F.T.; Oprea, T.I. Activation of dioxin response element (DRE)-associated genes by benzo[a]pyrene 3,6-quinone and benzo[a]pyrene 1,6-quinone in MCF-10A human mammary epithelial cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2007, 221, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyong, E.Q.; Lu, Y.; Goldstein, A.; Lebwohl, M.; Wei, H. Synergistic enhancement of H2O2 production in human epidermoid carcinoma cells by benzo[a]pyrene and ultraviolet A radiation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003, 188, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Yang, M.S. Benzo[a]pyrene-induced elevation of GSH level protects against oxidative stress and enhances xenobiotic detoxification in human HepG2 cells. Toxicology 2007, 235, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, P.; McGuire, J.; Rubio, C.; Gradin, K.; Whitelaw, M.L.; Pettersson, S.; Hanberg, A.; Poellinger, L. A constitutively active dioxin/aryl hydrocarbon receptor induces stomach tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9990–9995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Shigenaga, M.K.; Ames, B.N. Induction of cytochrome P4501A1 by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin or indolo(3,2-b)carbazole is associated with oxidative DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 2322–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, J.F.; Dalton, T.P.; Shertzer, H.G.; Puga, A. Induction of oxidative stress responses by dioxin and other ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Dose Response 2005, 3, 306–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knerr, S.; Schrenk, D. Carcinogenicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in experimental models. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2006, 50, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyde, M.E.; Wong, V.A.; Kim, A.H.; Lucier, G.W.; Walker, N.J. Induction of hepatic 8-oxo-deoxyguanosine adducts by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in Sprague-Dawley rats is female-specific and estrogen-dependent. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001, 14, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Trush, M.A.; Yager, J.D. DNA damage caused by reactive oxygen species originating from a copper-dependent oxidation of the 2-hydroxy catechol of estradiol. Carcinogenesis 1994, 15, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, A.S.; Oda, Y.; Stuart, G.R.; Glickman, B.W.; de Boer, J.G. Mutagenicity of TCDD in Big Blue transgenic rats. Mutat. Res. 2001, 478, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, F.; Vogel, C.F. Evidence supporting the hypothesis that one of the main functions of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor is mediation of cell stress responses. Biol. Chem. 2006, 387, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Dragan, Y.P.; Schrenk, D. Animal studies addressing the carcinogenicity of TCDD (or related compounds) with an emphasis on tumour promotion. Food Addit. Contam. 2000, 17, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloire, G.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Piette, J. NF-κB activation by reactive oxygen species: fifteen years later. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 1493–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Harraz, M.M.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.N.; Ding, W.; Zhang, Y.; Eggleston, T.; Yeaman, C.; Banfi, B.; Engelhardt, J.F. Nox2 and Rac1 regulate H2O2-dependent recruitment of TRAF6 to endosomal interleukin-1 receptor complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, B.; Wiegmann, K.; Tchikov, V.; Krut, O.; Pongratz, C.; Schramm, M.; Kleinridders, A.; Wunderlich, T.; Kashkar, H.; Utermohlen, O.; Bruning, J.C.; Schutze, S.; Kronke, M. Riboflavin kinase couples TNF receptor 1 to NADPH oxidase. Nature 2009, 460, 1159–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneburg, N.; Guicciardi, M.E.; Yin, X.M.; Gores, G.J. TNF-α-mediated lysosomal permeabilization is FAN and caspase 8/Bid dependent. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004, 287, G436–G443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Marwick, J.; Kirkham, P. Redox modulation of chromatin remodeling: impact on histone acetylation and deacetylation, NF-κB and pro-inflammatory gene expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 1255–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H.; Honda, S.; Maeda, S.; Chang, L.; Hirata, H.; Karin, M. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFα-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 2005, 120, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karin, M. The IκB kinase—a bridge between inflammation and cancer. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukawa, J.; Matsuzawa, A.; Takeda, K.; Ichijo, H. The ASK1-MAP kinase cascades in mammalian stress response. J. Biochem. 2004, 136, 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Valko, M.; Rhodes, C.J.; Moncol, J.; Izakovic, M.; Mazur, M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006, 160, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lison, D.; Carbonnelle, P.; Mollo, L.; Lauwerys, R.; Fubini, B. Physicochemical mechanism of the interaction between cobalt metal and carbide particles to generate toxic activated oxygen species. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1995, 8, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Hard metal containing tungsten carbide and cobalt. In The MAK Collection for Occupational Health and Safety, Part I: MAK Value Documentations; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2007; Volume 23, pp. 217–234.

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Henkler, F.; Brinkmann, J.; Luch, A. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis Induced by Metals and Xenobiotics. Cancers 2010, 2, 376-396. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers2020376

Henkler F, Brinkmann J, Luch A. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis Induced by Metals and Xenobiotics. Cancers. 2010; 2(2):376-396. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers2020376

Chicago/Turabian StyleHenkler, Frank, Joep Brinkmann, and Andreas Luch. 2010. "The Role of Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis Induced by Metals and Xenobiotics" Cancers 2, no. 2: 376-396. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers2020376

APA StyleHenkler, F., Brinkmann, J., & Luch, A. (2010). The Role of Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis Induced by Metals and Xenobiotics. Cancers, 2(2), 376-396. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers2020376