Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Human AC16 Cardiomyocytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Regents

2.2. Materials Preparation

2.3. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.4. Measurement of Cellular Apoptosis

2.5. Western Blot

2.6. ROS Detection

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

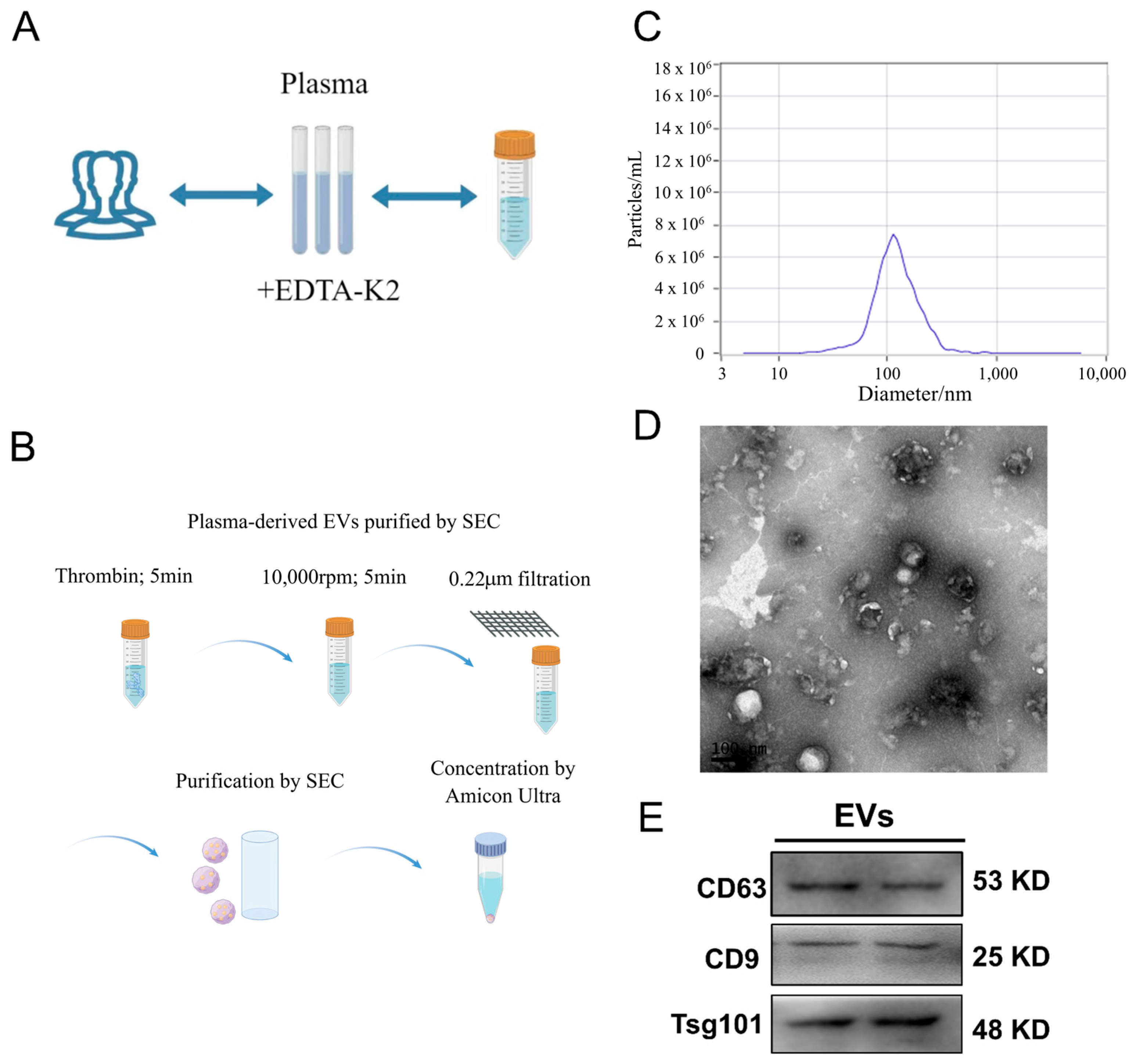

3.1. EV Characterization

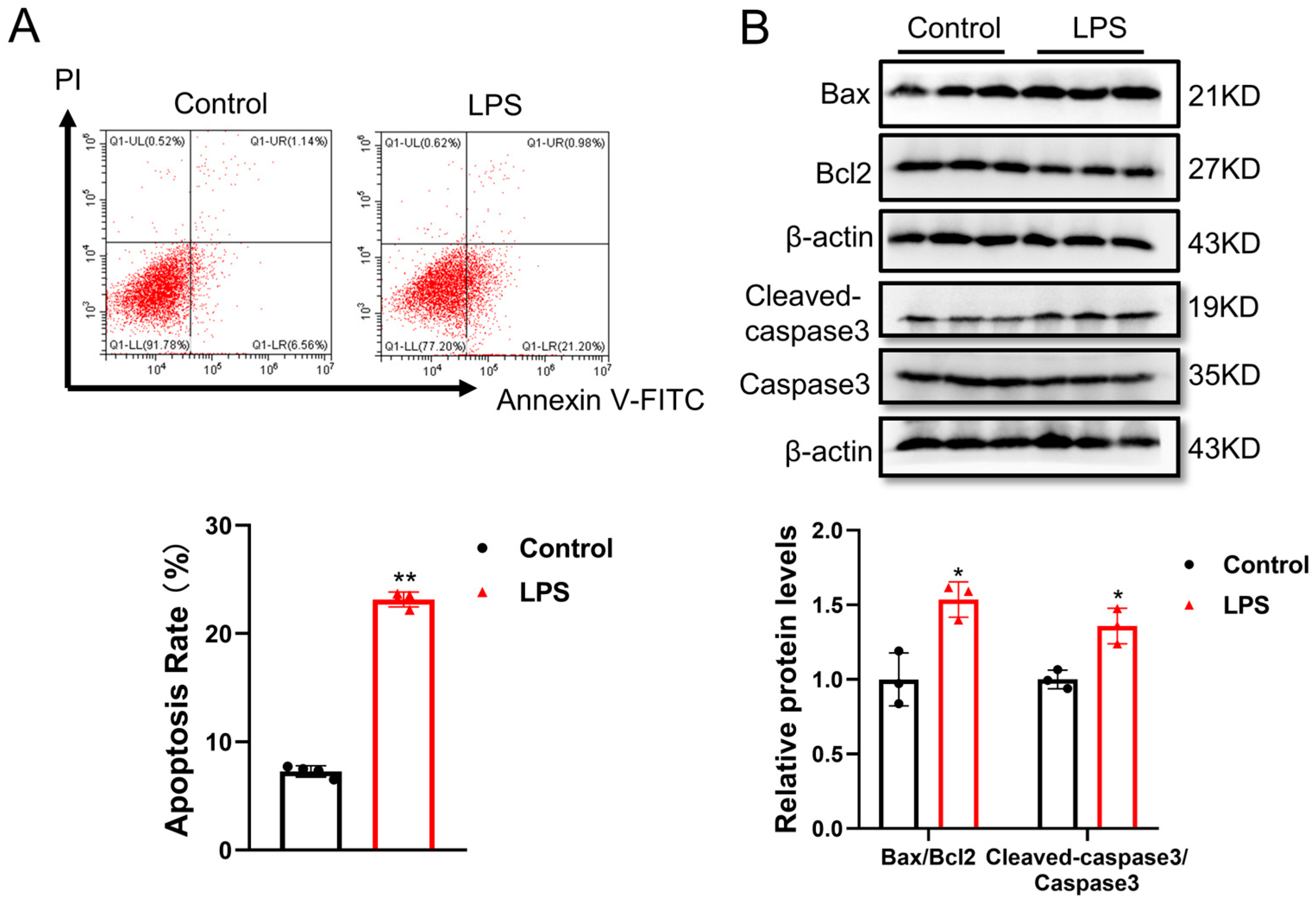

3.2. LPS-Induced Cell Apoptosis in Human AC16 Cardiomyocytes

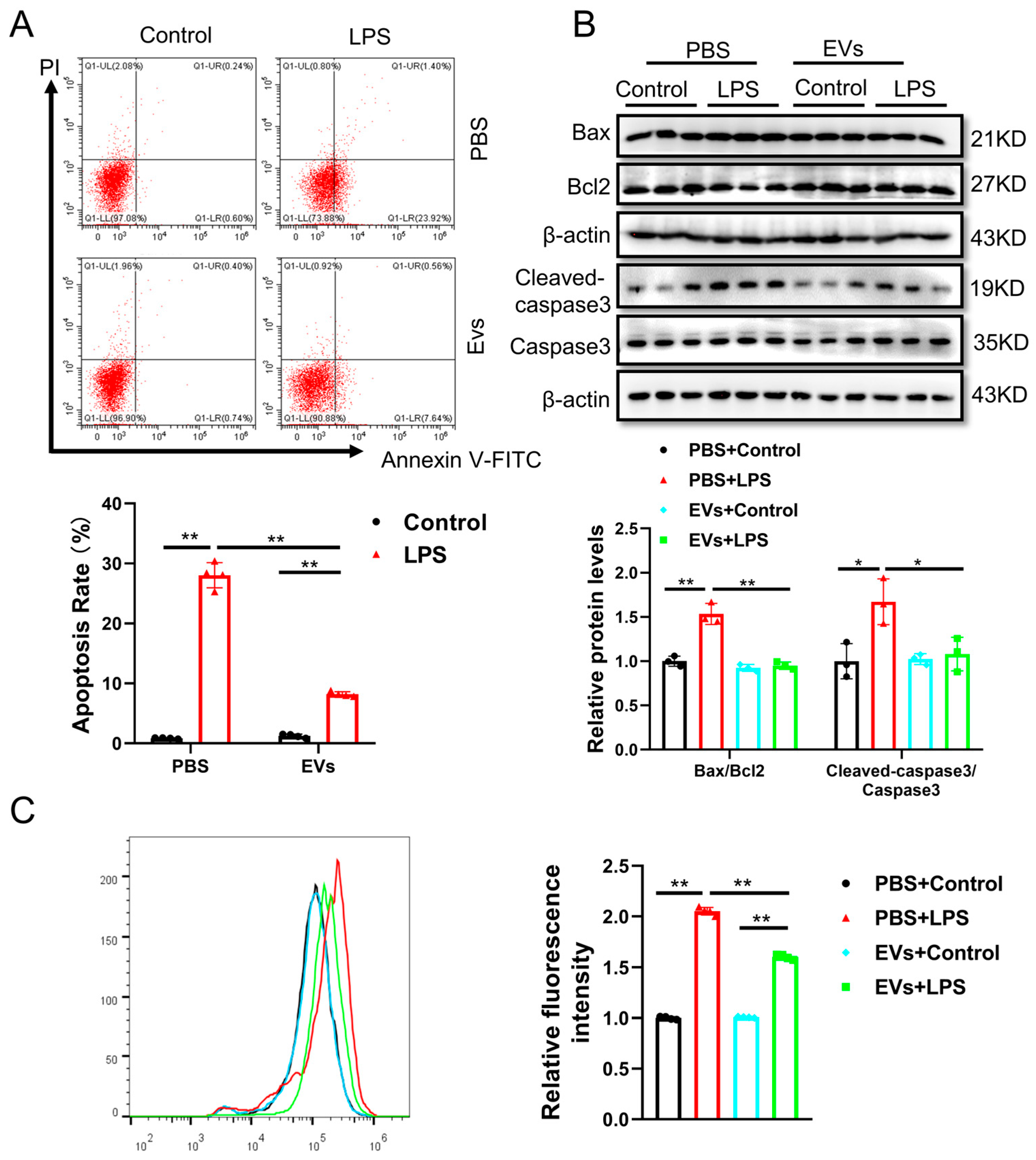

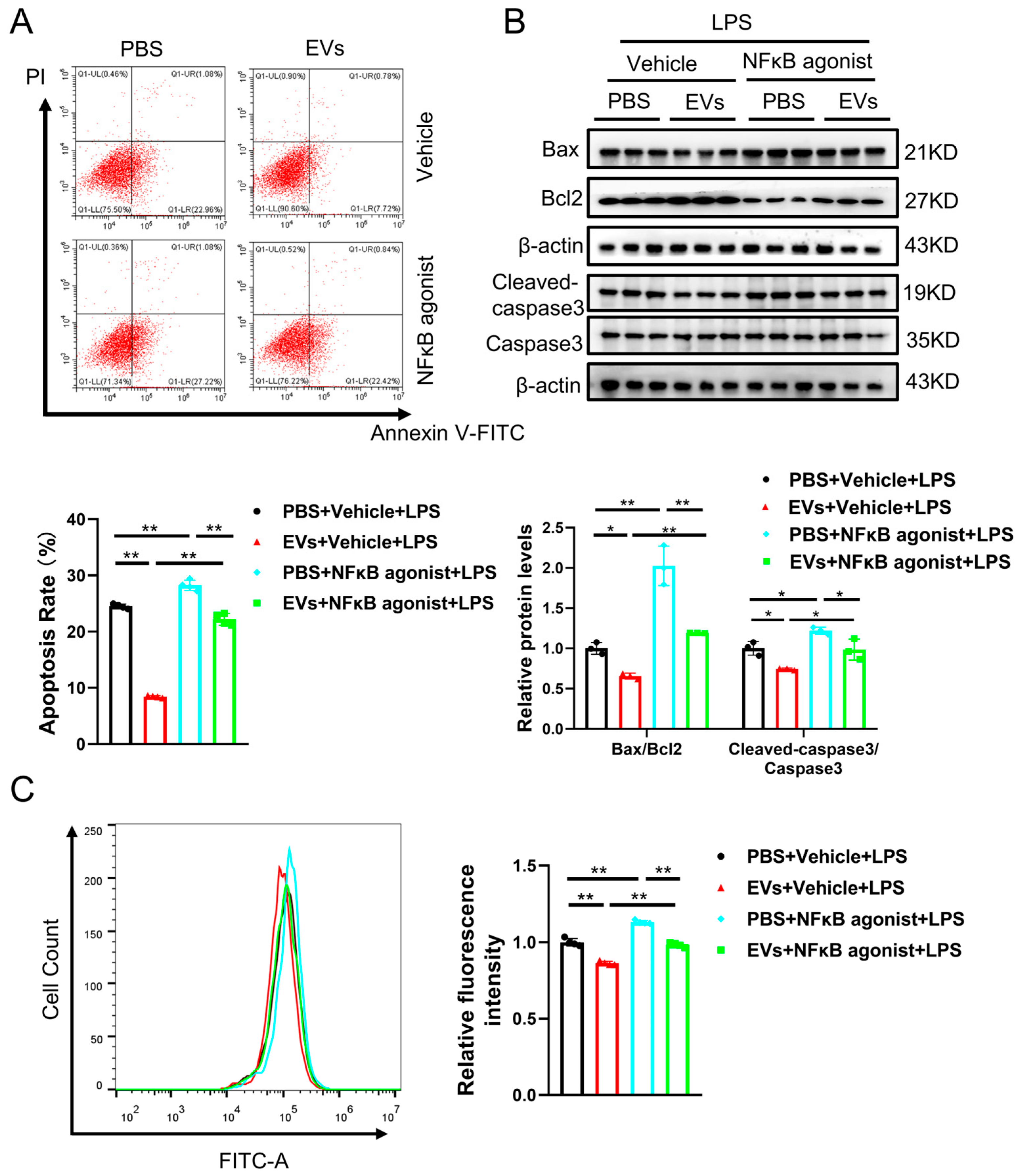

3.3. Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Attenuate LPS-Induced Cell Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Human AC16 Cardiomyocytes

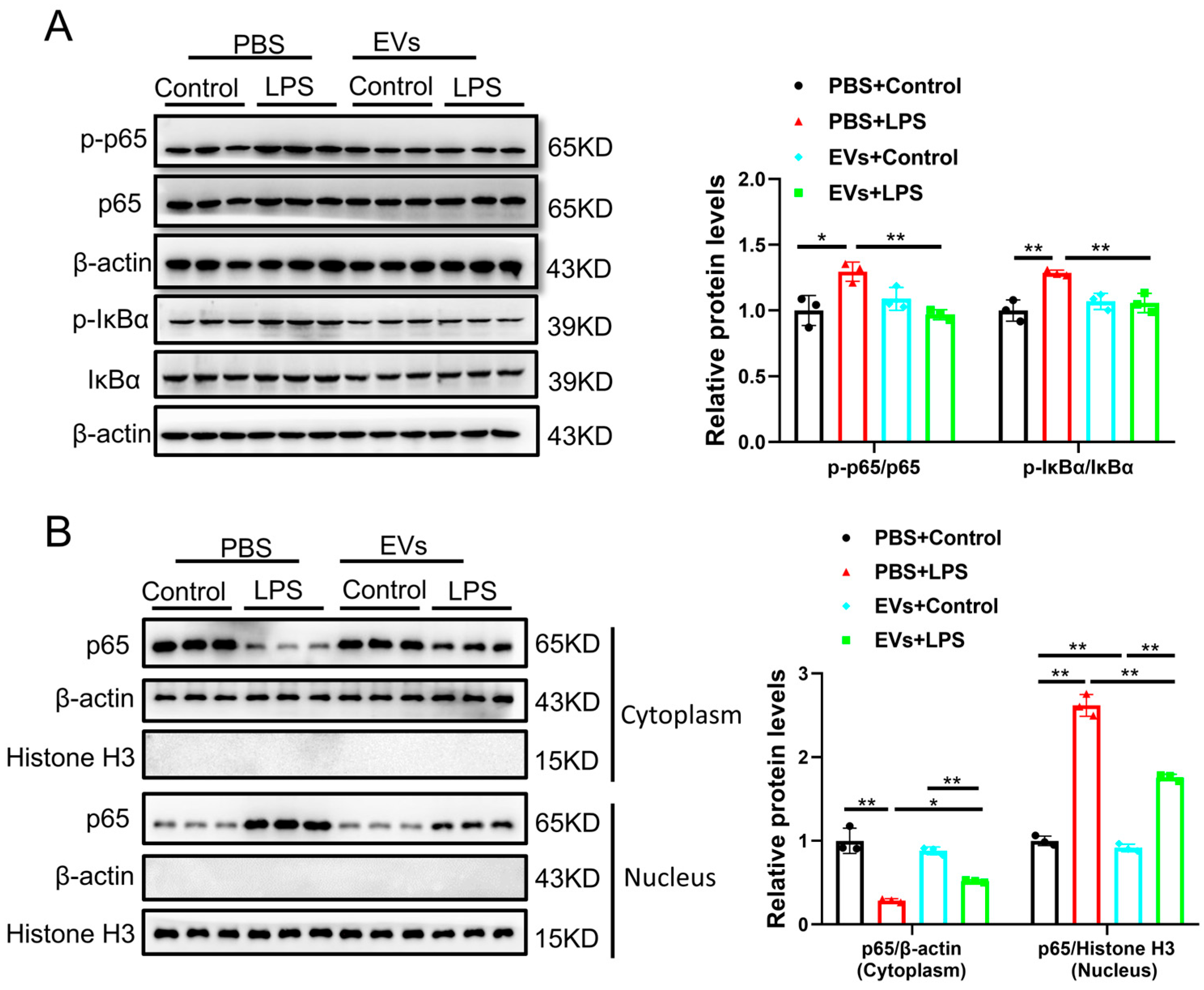

3.4. Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit LPS-Activated NF-κB p65 Signaling Pathway in AC16 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Yu, X.; Li, H.; Lv, X.; Lu, D.; Wang, H. β1-adrenoceptor stimulation promotes LPS-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through activating PKA and enhancing CaMKII and IκBα phosphorylation. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, H.P.; Fan, J.; Vallejo, J.G.; Dong, J.W.; Chen, X.; Houser, S.R.; Mann, D.L. Negative inotropic effects of high-mobility group box 1 protein in isolated contracting cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H1490–H1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmeier, T.G.; Arnemann, P.H.; Hessler, M.; Seidel, L.M.; Becker, K.; Morelli, A.; Rehberg, S.W.; Ertmer, C. Comparison of first-line and second-line terlipressin versus sole norepinephrine in fulminant ovine septic shock. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Pan, P.; Yan, P.; Long, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, R.; Wen, B.; Xie, L.; Liu, D. Role of vimentin in modulating immune cell apoptosis and inflammatory responses in sepsis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Liu, F.; Sun, Z.; Peng, Z.; You, T.; Yu, Z. LncRNA NEAT1 promotes apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis models by targeting miR-590-3p. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 3290–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Li, X.F.; Liu, M.H.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, S.-S.; Jiang, X. Procyanidin B2 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis by suppressing the Bcl2/Bax and NF-κB signalling pathways in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Kim, H. Evaluation of in vitro anti-inflammatory activities and protective effect of fermented preparations of Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae on intestinal barrier function against lipopolysaccharide insult. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 363076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawano, M.; Miyoshi, M.; Miyazaki, T. Lactobacillus helveticus SBT2171 induces A20 expression via Toll-like receptor 2 signaling and inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of nuclear factor-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases in peritoneal macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Yang, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tu, F.; Ha, T.; Liu, L.; Williams, D.L.; Li, C. Endothelial cell HSPA12B and yes-associated protein cooperatively regulate angiogenesis following myocardial infarction. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e140682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Tang, X.; Zheng, T.; Li, S.; Ren, H.; Wu, H.; Peng, F.; Gong, L. Plasma-derived extracellular vesicles transfer microRNA-130a-3p to alleviate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeting ATG16L1. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 389, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ni, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Wei, M.; Li, G.; Bei, Y. Platelet membrane-fused circulating extracellular vesicles protect the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2300052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, L.; Vassalli, G. Exosomes: Therapy delivery tools and biomarkers of diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 174, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, M.; Nawaz, M.; Papadimitriou, A.; Angerfors, A.; Camponeschi, A.; Na, M.; Hölttä, M.; Skantze, P.; Johansson, S.; Sundqvist, M.; et al. Linkage between endosomal escape of LNP-mRNA and loading into EVs for transport to other cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhao, L.; Yin, X.; Ai, S.; Hu, M.; Pan, X.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, S.; Li, G.; et al. Human Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Protect Against Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via HSP27 Phosphorylation. Adv. Ther. 2024, 7, 2400006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Maimaitiaili, R.; Yao, J.; Xie, Y.; Qiang, S.; Hu, F.; Li, X.; Shi, C.; Jia, P.; Yang, H.; et al. Percutaneous intracoronary delivery of plasma extracellular vesicles protects the myocardium against ischemia-reperfusion injury in Canis. Hypertension 2021, 78, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Sun, P.; Yuan, Y.; Peng, J.; Yan, J.; Du, J.; et al. Specific inhibition of CYP4A alleviates myocardial oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by advanced glycation end-products. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoiliqy, M.; Wen, J.; Xu, B.; Sun, Y.C.; Lian, M.Q.; Li, Y.L.; Qaed, E.; Al-Azab, M.; Chen, D.-P.; Shopit, A.; et al. Cinnamaldehyde protects against rat intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injuries by synergistic inhibition of NF-κB and p53. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Hai, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ye, Q. Heparin alleviates LPS-induced endothelial injury by regulating the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Z.; He, Y.; Ming, H.; Lei, S.; Leng, Y.; Xia, Z.Y. Lipopolysaccharide aggravates high glucose- and hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury through activating ROS-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis in H9C2 cardiomyocytes. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 8151836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandagale, A.; Lindahl, B.; Lind, S.B.; Shevchenko, G.; Siegbahn, A.; Christersson, C. Plasma-derived extracellular vesicles from myocardial infarction patients inhibit tumor necrosis factor-α-induced cardiac cell death. Curr. Res. Transl. Med. 2022, 70, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Yu, T.; Liu, D.; Shi, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Sepsis plasma-derived exosomal miR-1-3p induces endothelial cell dysfunction by targeting SERP1. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraju, V.; Joshi, M.; Suresh, S.; Sanchez, J.A.; Maulik, N.; Maulik, G. Diabetes, oxidative stress, molecular mechanism, and cardiovascular disease—An overview. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2012, 22, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, H.; Shen, Q.; Wang, C.; Yin, T. Up-regulation of glycolysis promotes the stemness and EMT phenotypes in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Ma, T. Peroxiredoxin2 (Prdx2) reduces oxidative stress and apoptosis of myocardial cells induced by acute myocardial infarction by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e926281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, R.S.; Kaplinskiy, V.; Kitsis, R.N. Cell death in the pathogenesis of heart disease: Mechanisms and significance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2010, 72, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hu, F.; Jiao, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, J.; You, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes suppress M1 macrophage polarization through the ROS-MAPK-NF-κB p65 signaling pathway after spinal cord injury. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lenardo, M.J.; Baltimore, D. 30 years of NF-κB: A blossoming of relevance to human pathobiology. Cell 2017, 168, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, C.; Xia, H. Downregulation of p300/CBP-associated factor inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis via suppression of NF-κB pathway in ischaemia/reperfusion injury rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 10224–10235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, M.J.; Hong, S.G.; Lee, J.W.; Jeong, W.S. Red ginseng marc oil inhibits iNOS and COX-2 via NF-κB and p38 pathways in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Molecules 2012, 17, 13769–13786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, J.A.; Mitchell, J.P.; Cook, S.J. Inhibitory feedback control of NF-κB signalling in health and disease. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 2619–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelarayan, L.; Renger, A.; Noack, C.; Zafiriou, M.P.; Gehrke, C.; van der Nagel, R.; Dietz, R.; de Windt, L.; Bergmann, M.W. NF-κB activation is required for adaptive cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 84, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.J.; Schips, T.G.; Wietelmann, A.; Kruger, M.; Brunner, C.; Sauter, M.; Klingel, K.; Böttger, T.; Braun, T.; Wirth, T. Cardiomyocyte-specific IκB kinase (IKK)/NF-κB activation induces reversible inflammatory cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11794–11799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Yang, T.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y. Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Human AC16 Cardiomyocytes. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020174

Yang Y, Yang T, Li Z, Zhu Y. Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Human AC16 Cardiomyocytes. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(2):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020174

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yuli, Tingting Yang, Zhihong Li, and Youshuang Zhu. 2026. "Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Human AC16 Cardiomyocytes" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 2: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020174

APA StyleYang, Y., Yang, T., Li, Z., & Zhu, Y. (2026). Plasma-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Inhibit Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Human AC16 Cardiomyocytes. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(2), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020174