The Involvement of MicroRNAs in Innate Immunity and Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Airway Epithelial Cells

3.1. Dysregulation of Airway Epithelial Cells in Cystic Fibrosis

3.2. Contribution of miRNAs to Airway Epithelial Cell Dysfunction in Cystic Fibrosis

3.2.1. Overexpressed miRNAs

3.2.2. Downregulated miRNAs

4. Resident and Recruited Lung Macrophages

4.1. Dysfunction of Macrophages in Cystic Fibrosis

4.2. Contribution of miRNAs to Macrophage Dysfunction in Cystic Fibrosis

5. Dysregulation of Neutrophils in Cystic Fibrosis

Contribution of miRNAs to Circulating Innate Immune Cell Dysfunction in Cystic Fibrosis

6. Genomic and Transcriptomic Studies

7. MicroRNAs in Biological Fluids in Cystic Fibrosis Patients

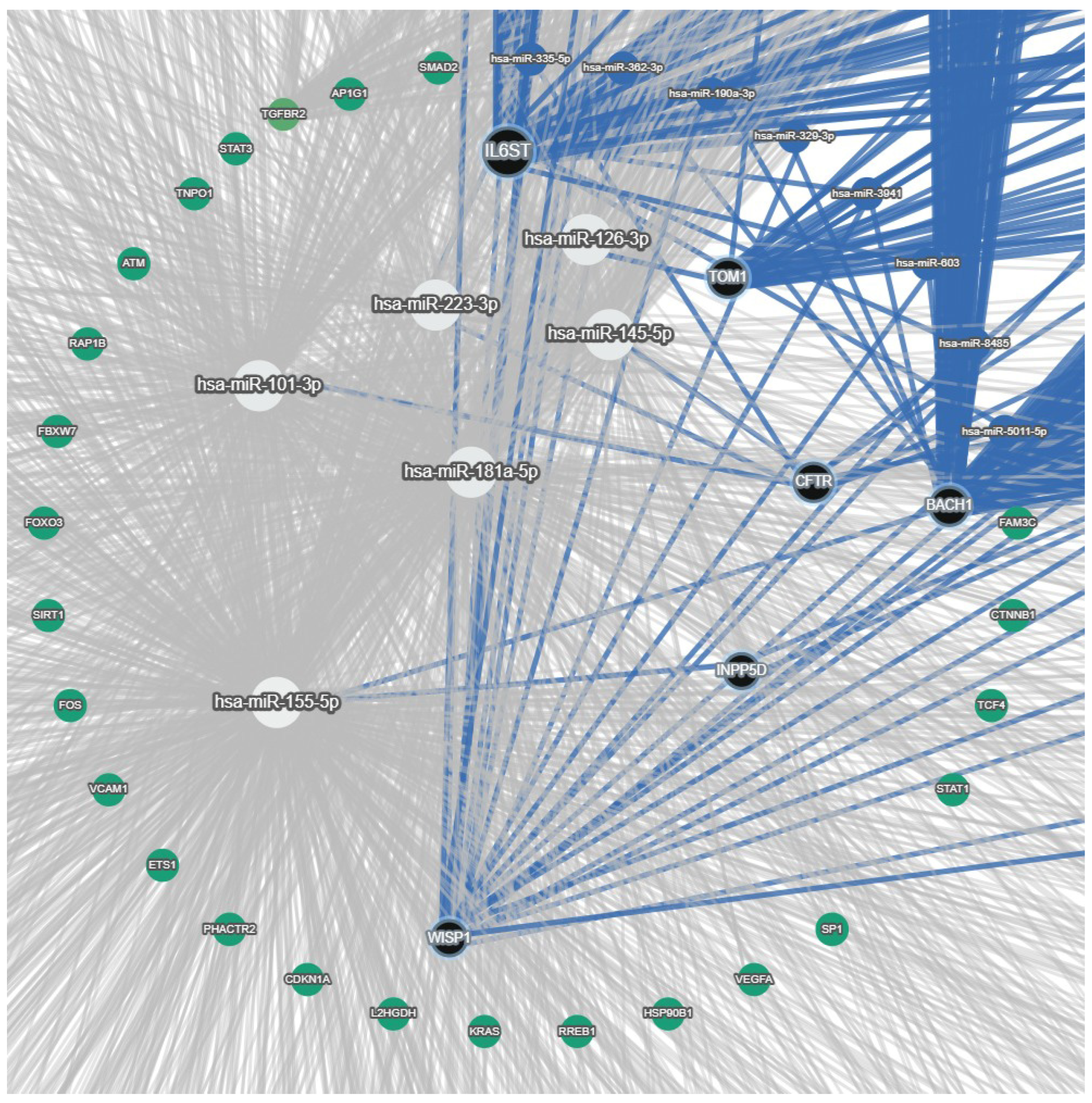

8. Compartmental Distribution of Cystic Fibrosis-Associated miRNAs

9. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rowe, S.M.; Miller, S.; Sorscher, E.J. Cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1992–2001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mall, M.A.; Burgel, P.R.; Castellani, C.; Davies, J.C.; Salathe, M.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L. Cystic fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Elborn, J.S. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2519–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoltz, D.A.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Welsh, M.J. Origins of cystic fibrosis lung disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1574–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, R.C. Evidence for airway surface dehydration as the initiating event in CF airway disease. J. Intern. Med. 2007, 261, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, M.A.; Davies, J.C.; Donaldson, S.H.; Jain, R.; Chalmers, J.D.; Shteinberg, M. Neutrophil serine proteases in cystic fibrosis: Role in disease pathogenesis and rationale as a therapeutic target. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2024, 33, 240001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, B.D.; Zorn, B.T.; Radicioni, G.; Livengood, S.S.; Kumagai, T.; Dang, H.; Ceppe, A.; Clapp, P.W.; Tunney, M.; Elborn, J.S.; et al. Cystic Fibrosis Airway Mucus Hyperconcentration Produces a Vicious Cycle of Mucin, Pathogen, and Inflammatory Interactions that Promotes Disease Persistence. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 67, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Annual Data Report; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Flight, W.G.; Bright-Thomas, R.J.; Tilston, P.; Mutton, K.J.; Guiver, M.; Morris, J.; Webb, A.K.; Jones, A.M. Incidence and clinical impact of respiratory viruses in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2014, 69, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffard, A.; Lambert, V.; Salleron, J.; Herwegh, S.; Engelmann, I.; Pinel, C.; Pin, I.; Perrez, T.; Prevotat, A.; Dewilde, A.; et al. Virus and cystic fibrosis: Rhinoviruses are associated with exacerbations in adult patients. J. Clin. Virol. 2014, 60, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, N.T.; Bardou, O.; Prive, A.; Maille, E.; Adam, D.; Lingee, S.; Ferraro, P.; Desrosiers, M.Y.; Coraux, C.; Brochiero, E. Improvement of defective cystic fibrosis airway epithelial wound repair after CFTR rescue. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1390–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, M.D.; Quaresma, M.C.; Pankonien, I. What Role Does CFTR Play in Development, Differentiation, Regeneration and Cancer? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Umer, H.M.; Björkqvist, M.; Roomans, G.M. ENaC, iNOS, mucins expression and wound healing in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial and submucosal cells. Cell. Biol. Int. Rep. 2014, 21, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, E.L.; Hirsch, M.J.; Prokopczuk, F.; Jones, L.I.; Martinez, E.; Barnes, J.W.; Krick, S. Wound repair and immune function in the Pseudomonas infected CF lung: Before and after highly effective modulator therapy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1566495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conese, M.; Di Gioia, S. Pathophysiology of Lung Disease and Wound Repair in Cystic Fibrosis. Pathophysiology 2021, 28, 155–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conese, M.; Castellani, S.; D’Oria, S.; di Gioia, S.; Montemurro, P. Role of Neutrophils in Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease. In Role of Neutrophils in Disease Pathogenesis; Khajah, M.A., Ed.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2017; pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, D.G.; Bell, S.C.; Elborn, J.S. Neutrophils in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2009, 64, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, C.; Costantini, D.; Rocchi, A.; Cariani, L.; Garlaschi, M.L.; Tirelli, S.; Calori, G.; Copreni, E.; Conese, M. Cytokine levels in sputum of cystic fibrosis patients before and after antibiotic therapy. Ped. Pulmunol. 2005, 40, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, R.C.; Farh, K.K.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, D.P. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, M.; Ghasemi, H.; Bazhan, D.; Bolbanabad, N.M.; Rahdan, F.; Arianfar, N.; Vahedi, F.; Khatami, S.H.; Taheri-Anganeh, M.; Aiiashi, S.; et al. MicroRNAs in disease States. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 569, 120187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneville, F.; Ruffin, M.; Guillot, L.; Rousselet, N.; Le Rouzic, P.; Corvol, H.; Tabary, O. New insights about miRNAs in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, P.; Sonneville, F.; Corvol, H.; Tabary, O. Emerging microRNA Therapeutic Approaches for Cystic Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Sadroddiny, E. MicroRNAs in lung diseases: Recent findings and their pathophysiological implications. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Bonfield, T.L. Update on Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Cystic Fibrosis. Clin. Chest. Med. 2022, 43, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.S.; Prince, A. Cystic fibrosis: A mucosal immunodeficiency syndrome. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEO DataSets. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term=(Cystic+fibrosis+AND+miRNA+Expression)+AND+%22Homo+sapiens%22%5Bporgn%3A__txid9606%5D. (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- McGeary, S.E.; Lin, K.S.; Shi, C.Y.; Pham, T.M.; Bisaria, N.; Kelley, G.M.; Bartel, D.P. The biochemical basis of microRNA targeting efficacy. Science 2019, 366, eaav1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Zhou, G.; Soufan, O.; Xia, J. miRNet 2.0: Network-based visual analytics for miRNA functional analysis and systems biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W244–W251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F.; Aparicio-Puerta, E.; Li, Y.; Fehlmann, T.; Kehl, T.; Wagner, V.; Ray, K.; Ludwig, N.; Lenhof, H.P.; Meese, E.; et al. miRTargetLink 2.0-interactive miRNA target gene and target pathway networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W409–W416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticht, C.; De La Torre, C.; Parveen, A.; Gretz, N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuksel, H.; Turkeli, A. Airway epithelial barrier dysfunction in the pathogenesis and prognosis of respiratory tract diseases in childhood and adulthood. Tissue Barriers 2017, 5, e1367458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, S.L.; Goldblatt, D.L.; Evans, S.E.; Tuvim, M.J.; Dickey, B.F. Airway Epithelial Innate Immunity. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 749077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitnauer, M.; Mijosek, V.; Dalpke, A.H. Control of local immunity by airway epithelial cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2016, 9, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, P.S.; McCray, P.B., Jr.; Bals, R. The innate immune function of airway epithelial cells in inflammatory lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, J.V.; Dickey, B.F. Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2233–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, B.F. Exoskeletons and exhalation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2082–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przysucha, N.; Gorska, K.; Krenke, R. Chitinases and Chitinase-Like Proteins in Obstructive Lung Diseases—Current Concepts and Potential Applications. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2020, 15, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Howard, B.A.; Liu, Y.; Neumann, A.K.; Li, L.; Menon, N.; Roach, T.; Kale, S.D.; Samuels, D.C.; Li, H.; et al. LYSMD3: A mammalian pattern recognition receptor for chitin. Cell. Rep. 2021, 36, 109392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Rodriguez, A.; Luong, A.U.; Allen, D.; Knight, J.M.; Kheradmand, F.; Corry, D.B. The immune response to airway mycosis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 62, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Sheikh, A.S.; Shen, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, D. Interleukin-13 stimulates MUC5AC expression via a STAT6-TMEM16A-ERK1/2 pathway in human airway epithelial cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 40, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zheng, T.; Homer, R.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Chen, N.Y.; Cohn, L.; Hamid, Q.; Elias, J.A. Acidic mammalian chitinase in asthmatic Th2 inflammation and IL-13 pathway activation. Science 2004, 304, 1678–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudakov, J.A.; Hanash, A.M.; van den Brink, M.R. Interleukin-22: Immunobiology and pathology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 747–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedik, S.; Madola, A.; Levine, A. IL-17C in human mucosal immunity: More than just a middle child. Cytokine 2021, 146, 155641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rose, V.; Molloy, K.; Gohy, S.; Pilette, C.; Greene, C.M. Airway Epithelium Dysfunction in Cystic Fibrosis and COPD. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 1309746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantin, A.M.; Hartl, D.; Konstan, M.W.; Chmiel, J.F. Inflammation in cystic fibrosis lung disease: Pathogenesis and therapy. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2015, 14, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.; Chmiel, J.; Berger, M. Chronic inflammation in the cystic fibrosis lung: Alterations in inter- and intracellular signaling. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2008, 34, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Cymberknoh, M.; Kerem, E.; Ferkol, T.; Elizur, A. Airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Thorax 2013, 68, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.S.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Tang, X.X.; Reznikov, L.; Abou Alaiwa, M.; Ernst, S.E.; Karp, P.H.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.L.; Heilmann, K.P.; Leidinger, M.R.; et al. Airway acidification initiates host defense abnormalities in cystic fibrosis mice. Science 2016, 351, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schogler, A.; Stokes, A.B.; Casaulta, C.; Regamey, N.; Edwards, M.R.; Johnston, S.L.; Jung, A.; Moeller, A.; Geiser, T.; Alves, M.P. Interferon response of the cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelium to major and minor group rhinovirus infection. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2016, 15, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, F.; Gruenberger, M.; Kowalski, H.; Machat, H.; Huettinger, M.; Kuechler, E.; Blaas, D. Members of the low density lipoprotein receptor family mediate cell entry of a minor-group common cold virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 1839–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, J.M.; Davis, G.; Meyer, A.M.; Forte, C.P.; Yost, S.C.; Marlor, C.W.; Kamarck, M.E.; McClelland, A. The major human rhinovirus receptor is ICAM-1. Cell 1989, 56, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauletbaev, N.; Das, M.; Cammisano, M.; Chen, H.; Singh, S.; Kooi, C.; Leigh, R.; Beaudoin, T.; Rousseau, S.; Lands, L.C. Rhinovirus Load Is High despite Preserved Interferon-beta Response in Cystic Fibrosis Bronchial Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofoluwe, A.; Zoso, A.; Bacchetta, M.; Lemeille, S.; Chanson, M. Immune response of polarized cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells infected with Influenza A virus. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021, 20, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Prince, A. Type I interferon response to extracellular bacteria in the airway epithelium. Trends Immunol. 2011, 32, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, D.; Cohen, T.S.; Alhede, M.; Harfenist, B.S.; Martin, F.J.; Prince, A. Induction of type I interferon signaling by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is diminished in cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauber, H.P.; Tulic, M.K.; Tsicopoulos, A.; Wallaert, B.; Olivenstein, R.; Daigneault, P.; Hamid, Q. Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 expression in the bronchial mucosa of patients with cystic fibrosis. Can. Respir. J. 2005, 12, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, C.M.; Carroll, T.P.; Smith, S.G.; Taggart, C.C.; Devaney, J.; Griffin, S.; O’Neill, S.J.; McElvaney, N.G. TLR-induced inflammation in cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, A.; Soong, G.; Sokol, S.; Reddy, B.; Gomez, M.I.; Van Heeckeren, A.; Prince, A. Toll-like receptors in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2004, 30, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, G.; Yildirim, A.O.; Rubin, B.K.; Gruenert, D.C.; Henke, M.O. TLR-4-mediated innate immunity is reduced in cystic fibrosis airway cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010, 42, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, G.; Chillappagari, S.; Rubin, B.K.; Gruenert, D.C.; Henke, M.O. Reduced surface toll-like receptor-4 expression and absent interferon-gamma-inducible protein-10 induction in cystic fibrosis airway cells. Exp. Lung Res. 2011, 37, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vencken, S.F.; Greene, C.M. Toll-Like Receptors in Cystic Fibrosis: Impact of Dysfunctional microRNA on Innate Immune Responses in the Cystic Fibrosis Lung. J. Innate Immun. 2016, 8, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Reyna, S.; Holbrook, J.; Jarosz-Griffiths, H.H.; Peckham, D.; McDermott, M.F. Dysregulated signalling pathways in innate immune cells with cystic fibrosis mutations. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2020, 77, 4485–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquot, J.; Tabary, O.; Le Rouzic, P.; Clement, A. Airway epithelial cell inflammatory signalling in cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 1703–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrabino, S.; Carpani, D.; Livraghi, A.; Di Cicco, M.; Costantini, D.; Copreni, E.; Colombo, C.; Conese, M. Dysregulated interleukin-8 secretion and NF-kappaB activity in human cystic fibrosis nasal epithelial cells. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2006, 5, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, T.; Look, D.; Ferkol, T. NF-kB activation and sustained IL-8 gene expression in primary cultures of cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells stimulated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005, 288, L471–L479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boncoeur, E.; Criq, V.S.; Bonvin, E.; Roque, T.; Henrion-Caude, A.; Gruenert, D.C.; Clement, A.; Jacquot, J.; Tabary, O. Oxidative stress induces extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase in cystic fibrosis lung epithelial cells: Potential mechanism for excessive IL-8 expression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raia, V.; Maiuri, L.; Ciacci, C.; Ricciardelli, I.; Vacca, L.; Auricchio, S.; Cimmino, M.; Cavaliere, M.; Nardone, M.; Cesaro, A.; et al. Inhibition of p38 mitogen activated protein kinase controls airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2005, 60, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghe, C.; Remouchamps, C.; Hennuy, B.; Vanderplasschen, A.; Chariot, A.; Tabruyn, S.P.; Oury, C.; Bours, V. Role of IKK and ERK pathways in intrinsic inflammation of cystic fibrosis airways. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 73, 1982–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Johnson, X.D.; Iazvovskaia, S.; Tan, A.; Lin, A.; Hershenson, M.B. Signaling intermediates required for NF-kappa B activation and IL-8 expression in CF bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003, 284, L307–L315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimessi, A.; Vitto, V.A.M.; Patergnani, S.; Pinton, P. Update on Calcium Signaling in Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 581645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Xu, W.; Bose, S.; Banerjee, A.K.; Haque, S.J.; Erzurum, S.C. Impaired nitric oxide synthase-2 signaling pathway in cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004, 287, L374–L381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villella, V.R.; Esposito, S.; Bruscia, E.M.; Vicinanza, M.; Cenci, S.; Guido, S.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Carnuccio, R.; De Matteis, M.A.; Luini, A.; et al. Disease-relevant proteostasis regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, M.; Martignetti, L.; Cornet, M.; Kelly-Aubert, M.; Sermet, I.; Calzone, L.; Stoven, V. From CFTR to a CF signalling network: A systems biology approach to study Cystic Fibrosis. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Xian, Y.; Tang, Y.; Ye, J.; Reza, F.; He, G.; Wen, X.; Jiang, X. The multiple roles of interferon regulatory factor family in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Balakathiresan, N.S.; Dalgard, C.; Gutti, U.; Armistead, D.; Jozwik, C.; Srivastava, M.; Pollard, H.B.; Biswas, R. Elevated miR-155 promotes inflammation in cystic fibrosis by driving hyperexpression of interleukin-8. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 11604–11615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, P.; Marchal-Duval, E.; Sonneville, F.; Blouquit-Laye, S.; Rousselet, N.; Le Rouzic, P.; Corvol, H.; Tabary, O. Small RNA and transcriptome sequencing reveal the role of miR-199a-3p in inflammatory processes in cystic fibrosis airways. J. Pathol. 2018, 245, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, P.; Foussigniere, T.; Rousselet, N.; Rebeyrol, C.; Porter, J.C.; Corvol, H.; Tabary, O. miR-636: A Newly-Identified Actor for the Regulation of Pulmonary Inflammation in Cystic Fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, A.; Varilh, J.; Bleuse, S.; Deletang, K.; Bonini, J.; Bergougnoux, A.; Brochiero, E.; Koenig, M.; Claustres, M.; Taulan-Cadars, M. miRNA repertoires of cystic fibrosis ex vivo models highlight miR-181a and miR-101 that regulate WISP1 expression. J. Pathol. 2021, 253, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oglesby, I.K.; Bray, I.M.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Stallings, R.L.; O’Neill, S.J.; McElvaney, N.G.; Greene, C.M. miR-126 is downregulated in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells and regulates TOM1 expression. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 1702–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oglesby, I.K.; Vencken, S.F.; Agrawal, R.; Gaughan, K.; Molloy, K.; Higgins, G.; McNally, P.; McElvaney, N.G.; Mall, M.A.; Greene, C.M. miR-17 overexpression in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells decreases interleukin-8 production. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 46, 1350–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, E.; Borgatti, M.; Montagner, G.; Bianchi, N.; Finotti, A.; Lampronti, I.; Bezzerri, V.; Dechecchi, M.C.; Cabrini, G.; Gambari, R. Expression of microRNA-93 and Interleukin-8 during Pseudomonas aeruginosa-mediated induction of proinflammatory responses. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakami, M.; Yokosawa, H. Tom1 (target of Myb 1) is a novel negative regulator of interleukin-1- and tumor necrosis factor-induced signaling pathways. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 27, 564–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindskog, C.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallstrom, B.; Edlund, K.; Hellwig, B.; Rahnenfuhrer, J.; Kampf, C.; Uhlen, M.; Ponten, F.; Micke, P. The lung-specific proteome defined by integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 5184–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aegerter, H.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Jakubzick, C.V. Biology of lung macrophages in health and disease. Immunity 2022, 55, 1564–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussell, T.; Bell, T.J. Alveolar macrophages: Plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, A.J.; Mathie, S.A.; Gregory, L.G.; Lloyd, C.M. Pulmonary macrophages: Key players in the innate defence of the airways. Thorax 2015, 70, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goritzka, M.; Makris, S.; Kausar, F.; Durant, L.R.; Pereira, C.; Kumagai, Y.; Culley, F.J.; Mack, M.; Akira, S.; Johansson, C. Alveolar macrophage-derived type I interferons orchestrate innate immunity to RSV through recruitment of antiviral monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mould, K.J.; Moore, C.M.; McManus, S.A.; McCubbrey, A.L.; McClendon, J.D.; Griesmer, C.L.; Henson, P.M.; Janssen, W.J. Airspace Macrophages and Monocytes Exist in Transcriptionally Distinct Subsets in Healthy Adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchett, W.J.; Cook, J.; Oliver, R.A.; Bruno, N.; Walker, S.A.; Stolting, H.; Mack, M.; O’Garra, A.; Saglani, S.; Lloyd, C.M. Airway macrophage-intrinsic TGF-beta1 regulates pulmonary immunity during early-life allergen exposure. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 1892–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, L.; Wiscombe, S.; Reynolds, G.; McDonald, D.; Fuller, A.; Green, K.; Filby, A.; Forrest, I.; Ruchaud-Sparagano, M.H.; Scott, J.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide inhalation recruits monocytes and dendritic cell subsets to the alveolar airspace. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepen, T.; McMenamin, C.; Oliver, J.; Kraal, G.; Holt, P.G. Regulation of immune response to inhaled antigen by alveolar macrophages: Differential effects of in vivo alveolar macrophage elimination on the induction of tolerance vs. immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 1991, 21, 2845–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ural, B.B.; Yeung, S.T.; Damani-Yokota, P.; Devlin, J.C.; de Vries, M.; Vera-Licona, P.; Samji, T.; Sawai, C.M.; Jang, G.; Perez, O.A.; et al. Identification of a nerve-associated, lung-resident interstitial macrophage subset with distinct localization and immunoregulatory properties. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eaax8756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedoret, D.; Wallemacq, H.; Marichal, T.; Desmet, C.; Quesada Calvo, F.; Henry, E.; Closset, R.; Dewals, B.; Thielen, C.; Gustin, P.; et al. Lung interstitial macrophages alter dendritic cell functions to prevent airway allergy in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 3723–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke-Ullmann, G.; Pfortner, C.; Walter, P.; Steinmuller, C.; Lohmann-Matthes, M.L.; Kobzik, L. Characterization of murine lung interstitial macrophages in comparison with alveolar macrophages in vitro. J. Immunol. 1996, 157, 3097–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, H.; Kayama, H.; Nakama, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Umemoto, E.; Takeda, K. IL-10-producing lung interstitial macrophages prevent neutrophilic asthma. Int. Immunol. 2016, 28, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, E.M.; Oliveira, V.L.S.; Boff, D.; Galvao, I. Pulmonary macrophages and their different roles in health and disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 141, 106095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makita, N.; Hizukuri, Y.; Yamashiro, K.; Murakawa, M.; Hayashi, Y. IL-10 enhances the phenotype of M2 macrophages induced by IL-4 and confers the ability to increase eosinophil migration. Int. Immunol. 2015, 27, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Sica, A.; Sozzani, S.; Allavena, P.; Vecchi, A.; Locati, M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Lu, Y.; Han, L.; Liu, G. Kinase AKT controls innate immune cell development and function. Immunology 2013, 140, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laird, M.H.; Rhee, S.H.; Perkins, D.J.; Medvedev, A.E.; Piao, W.; Fenton, M.J.; Vogel, S.N. TLR4/MyD88/PI3K interactions regulate TLR4 signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 85, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, M.; Mackman, N. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway limits lipopolysaccharide activation of signaling pathways and expression of inflammatory mediators in human monocytic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 32124–32132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prame Kumar, K.; Nicholls, A.J.; Wong, C.H.Y. Partners in crime: Neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in inflammation and disease. Cell. Tissue Res. 2018, 371, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soehnlein, O.; Lindbom, L. Phagocyte partnership during the onset and resolution of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossaint, J.; Zarbock, A. Tissue-specific neutrophil recruitment into the lung, liver, and kidney. J. Innate Immun. 2013, 5, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, B.A.; Kubes, P. Exploring the complex role of chemokines and chemoattractants in vivo on leukocyte dynamics. Immunol. Rev. 2019, 289, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.A.; Morales-Nebreda, L.; Markov, N.S.; Swaminathan, S.; Querrey, M.; Guzman, E.R.; Abbott, D.A.; Donnelly, H.K.; Donayre, A.; Goldberg, I.A.; et al. Circuits between infected macrophages and T cells in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Nature 2021, 590, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbrey, A.L.; Barthel, L.; Mohning, M.P.; Redente, E.F.; Mould, K.J.; Thomas, S.M.; Leach, S.M.; Danhorn, T.; Gibbings, S.L.; Jakubzick, C.V.; et al. Deletion of c-FLIP from CD11b(hi) Macrophages Prevents Development of Bleomycin-induced Lung Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 58, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misharin, A.V.; Morales-Nebreda, L.; Reyfman, P.A.; Cuda, C.M.; Walter, J.M.; McQuattie-Pimentel, A.C.; Chen, C.I.; Anekalla, K.R.; Joshi, N.; Williams, K.J.N.; et al. Monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages drive lung fibrosis and persist in the lung over the life span. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 2387–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, K.J.; Jackson, N.D.; Henson, P.M.; Seibold, M.; Janssen, W.J. Single cell RNA sequencing identifies unique inflammatory airspace macrophage subsets. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e126556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, T.; Shichino, S.; Ueha, S.; Bando, K.; Matsushima, K. Profibrotic properties of C1q(+) interstitial macrophages in silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 599, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck-Schimmer, B.; Schwendener, R.; Pasch, T.; Reyes, L.; Booy, C.; Schimmer, R.C. Alveolar macrophages regulate neutrophil recruitment in endotoxin-induced lung injury. Respir. Res. 2005, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.D.; Serhan, C.N. Resolution of acute inflammation in the lung. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2014, 76, 467–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbrey, A.L.; Curtis, J.L. Efferocytosis and lung disease. Chest 2013, 143, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveque, M.; Le Trionnaire, S.; Del Porto, P.; Martin-Chouly, C. The impact of impaired macrophage functions in cystic fibrosis disease progression. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017, 16, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Zhang, P.X.; Ferreira, E.; Caputo, C.; Emerson, J.W.; Tuck, D.; Krause, D.S.; Egan, M.E. Macrophages directly contribute to the exaggerated inflammatory response in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator−/− mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009, 40, 295–304, Erratum in Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 2561.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfield, T.L.; Hodges, C.A.; Cotton, C.U.; Drumm, M.L. Absence of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (Cftr) from myeloid-derived cells slows resolution of inflammation and infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012, 92, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, C.; Zhang, P.X.; O’Rourke, T.K.; Murray, T.S.; Wang, L.; Britto, C.J.; Koff, J.L.; Krause, D.S.; Egan, M.E.; Bruscia, E.M. Ezrin links CFTR to TLR4 signaling to orchestrate anti-bacterial immune response in macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, P.D.; Cifani, N.; Guarnieri, S.; Di Domenico, E.G.; Mariggio, M.A.; Spadaro, F.; Guglietta, S.; Anile, M.; Venuta, F.; Quattrucci, S.; et al. Dysfunctional CFTR alters the bactericidal activity of human macrophages against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, A.; Brown, M.E.; Deriy, L.V.; Li, C.; Szeto, F.L.; Chen, Y.; Huang, P.; Tong, J.; Naren, A.P.; Bindokas, V.; et al. CFTR regulates phagosome acidification in macrophages and alters bactericidal activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessich, J.L.; Nymon, A.B.; Moulton, L.A.; Dorman, D.; Ashare, A. Low levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 contribute to alveolar macrophage dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Weert-van Leeuwen, P.B.; Van Meegen, M.A.; Speirs, J.J.; Pals, D.J.; Rooijakkers, S.H.; Van der Ent, C.K.; Terheggen-Lagro, S.W.; Arets, H.G.; Beekman, J.M. Optimal complement-mediated phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by monocytes is cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-dependent. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, B.A.; Khweek, A.A.; Akhter, A.; Caution, K.; Kotrange, S.; Abdelaziz, D.H.; Newland, C.; Rosales-Reyes, R.; Kopp, B.; McCoy, K.; et al. Autophagy stimulation by rapamycin suppresses lung inflammation and infection by Burkholderia cenocepacia in a model of cystic fibrosis. Autophagy 2011, 7, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Bonfield, T.L. Cystic Fibrosis Lung Immunity: The Role of the Macrophage. J. Innate Immun. 2016, 8, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin-Le Jeune, K.; Le Jeune, A.; Jouneau, S.; Belleguic, C.; Roux, P.F.; Jaguin, M.; Dimanche-Boitre, M.T.; Lecureur, V.; Leclercq, C.; Desrues, B.; et al. Impaired functions of macrophage from cystic fibrosis patients: CD11b, TLR-5 decrease and sCD14, inflammatory cytokines increase. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruscia, E.M.; Zhang, P.X.; Satoh, A.; Caputo, C.; Medzhitov, R.; Shenoy, A.; Egan, M.E.; Krause, D.S. Abnormal trafficking and degradation of TLR4 underlie the elevated inflammatory response in cystic fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 6990–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.X.; Murray, T.S.; Villella, V.R.; Ferrari, E.; Esposito, S.; D’Souza, A.; Raia, V.; Maiuri, L.; Krause, D.S.; Egan, M.E.; et al. Reduced caveolin-1 promotes hyperinflammation due to abnormal heme oxygenase-1 localization in lipopolysaccharide-challenged macrophages with dysfunctional cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 5196–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Kim, H.P.; Nakahira, K.; Ryter, S.W.; Choi, A.M. The heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide pathway suppresses TLR4 signaling by regulating the interaction of TLR4 with caveolin-1. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 3809–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleriot, C.; Chakarov, S.; Ginhoux, F. Determinants of Resident Tissue Macrophage Identity and Function. Immunity 2020, 52, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oz, H.H.; Cheng, E.C.; Di Pietro, C.; Tebaldi, T.; Biancon, G.; Zeiss, C.; Zhang, P.X.; Huang, P.H.; Esquibies, S.S.; Britto, C.J.; et al. Recruited monocytes/macrophages drive pulmonary neutrophilic inflammation and irreversible lung tissue remodeling in cystic fibrosis. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.L.; Huang, X.Y.; Luo, Y.F.; Tan, W.P.; Chen, P.F.; Guo, Y.B. Activation of M1 macrophages plays a critical role in the initiation of acute lung injury. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20171555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarique, A.A.; Sly, P.D.; Holt, P.G.; Bosco, A.; Ware, R.S.; Logan, J.; Bell, S.C.; Wainwright, C.E.; Fantino, E. CFTR-dependent defect in alternatively-activated macrophages in cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017, 16, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Reyna, S.; Scambler, T.; Holbrook, J.; Wong, C.; Jarosz-Griffiths, H.H.; Martinon, F.; Savic, S.; Peckham, D.; McDermott, M.F. Metabolic Reprograming of Cystic Fibrosis Macrophages via the IRE1alpha Arm of the Unfolded Protein Response Results in Exacerbated Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shrestha, C.L.; Kopp, B.T. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulators have differential effects on cystic fibrosis macrophage function. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.X.; Cheng, J.; Zou, S.; D’Souza, A.D.; Koff, J.L.; Lu, J.; Lee, P.J.; Krause, D.S.; Egan, M.E.; Bruscia, E.M. Pharmacological modulation of the AKT/microRNA-199a-5p/CAV1 pathway ameliorates cystic fibrosis lung hyper-inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luly, F.R.; Leveque, M.; Licursi, V.; Cimino, G.; Martin-Chouly, C.; Theret, N.; Negri, R.; Cavinato, L.; Ascenzioni, F.; Del Porto, P. MiR-146a is over-expressed and controls IL-6 production in cystic fibrosis macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKiernan, P.J.; Molloy, K.P.; Cryan, S.A.; McElvaney, N.G.; Greene, C.M. X Chromosome-encoded MicroRNAs Are Functionally Increased in Cystic Fibrosis Monocytes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 668–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.; Ding, E.; Hu, M.; Lagoo, A.S.; Datto, M.B.; Lagoo-Deenadayalan, S.A. SMAD4 is required for development of maximal endotoxin tolerance. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 5502–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.C.; Tsai, Y.F.; Pan, Y.L.; Hwang, T.L. Understanding the role of neutrophils in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Biomed. J. 2021, 44, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Y.; Nunez, G. Sterile inflammation: Sensing and reacting to damage. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Marand, A.; Muldur, S.; Hopke, A.; Leung, H.M.; De La Flor, D.; Park, G.; Pinsky, H.; Guthrie, L.B.; Tearney, G.J.; et al. Neutrophil dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021, 20, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.M.; Gray, R.D. Neutrophil extracellular traps and the dysfunctional innate immune response of cystic fibrosis lung disease: A review. J. Inflamm. 2017, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Nauseef, W.M. Neutrophil dysfunction in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis. Blood 2022, 139, 2622–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Ali, Z.S.; Sweezey, N.; Grasemann, H.; Palaniyar, N. Progression of Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease from Childhood to Adulthood: Neutrophils, Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET) Formation, and NET Degradation. Genes 2019, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandivier, R.W.; Henson, P.M.; Douglas, I.S. Burying the dead: The impact of failed apoptotic cell removal (efferocytosis) on chronic inflammatory lung disease. Chest 2006, 129, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.D.; Hardisty, G.; Regan, K.H.; Smith, M.; Robb, C.T.; Duffin, R.; Mackellar, A.; Felton, J.M.; Paemka, L.; McCullagh, B.N.; et al. Delayed neutrophil apoptosis enhances NET formation in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2018, 73, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makam, M.; Diaz, D.; Laval, J.; Gernez, Y.; Conrad, C.K.; Dunn, C.E.; Davies, Z.A.; Moss, R.B.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Herzenberg, L.A.; et al. Activation of critical, host-induced, metabolic and stress pathways marks neutrophil entry into cystic fibrosis lungs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5779–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirouvanziam, R.; Gernez, Y.; Conrad, C.K.; Moss, R.B.; Schrijver, I.; Dunn, C.E.; Davies, Z.A.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Herzenberg, L.A. Profound functional and signaling changes in viable inflammatory neutrophils homing to cystic fibrosis airways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 4335–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laval, J.; Touhami, J.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Conrad, C.; Taylor, N.; Battini, J.L.; Sitbon, M.; Tirouvanziam, R. Metabolic adaptation of neutrophils in cystic fibrosis airways involves distinct shifts in nutrient transporter expression. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 6043–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deny, M.; Popotas, A.; Hanssens, L.; Lefevre, N.; Arroba Nunez, L.A.; Ouafo, G.S.; Corazza, F.; Casimir, G.; Chamekh, M. Sex-biased expression of selected chromosome x-linked microRNAs with potent regulatory effect on the inflammatory response in children with cystic fibrosis: A preliminary pilot investigation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1114239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catellani, C.; Cirillo, F.; Graziano, S.; Montanini, L.; Marmiroli, N.; Gullì, M.; Street, M.E. MicroRNA global profiling in cystic fibrosis cell lines reveals dysregulated pathways related with inflammation, cancer, growth, glucose and lipid metabolism, and fertility: An exploratory study. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2022, 93, e2022133. [Google Scholar]

- De Santi, C.; Fernández, E.F.; Gaul, R.; Vencken, S.; Glasgow, A.; Oglesby, I.K.; Hurley, K.; Hawkins, F.; Mitash, N.; Mu, F.; et al. Precise targeting of miRNA sites restores CFTR activity in CF bronchial epithelial cells. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzarini, R.; Caffarini, M.; Tang, H.; Cerqueni, G.; Pellegrino, P.; Monsurro, V.; Di Primio, R.; Orciani, M. The senescent status of endothelial cells affects proliferation, inflammatory profile and SOX2 expression in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 120, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Fourcade, L.; Roussel, L.; Marabella, M.; Berube, J.; Nguyen, D.; Rousseau, S. IL-6 trans-signaling in cystic fibrosis bronchial cells potentiates TNF-alpha-driven ICAM-1 expression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1566482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, J.; Chalaris, A.; Schmidt-Arras, D.; Rose-John, S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2011, 1813, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ding, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.Q.; Qian, G.H.; Qian, W.G.; Cao, L.; Zhou, W.P.; Hou, M.; Lv, H.T. MiR-223-3p Alleviates Vascular Endothelial Injury by Targeting IL6ST in Kawasaki Disease. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 288, Corrigendum in Front. Pediatr. 2019, 17, 2449. [Google Scholar]

- Lutful Kabir, F.; Ambalavanan, N.; Liu, G.; Li, P.; Solomon, G.M.; Lal, C.V.; Mazur, M.; Halloran, B.; Szul, T.; Gerthoffer, W.T.; et al. MicroRNA-145 Antagonism Reverses TGF-beta Inhibition of F508del CFTR Correction in Airway Epithelia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, F.; Lazzeroni, P.; Catellani, C.; Sartori, C.; Amarri, S.; Street, M.E. MicroRNAs link chronic inflammation in childhood to growth impairment and insulin-resistance. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2018, 39, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, J.; Wei, X.; Niu, C.; Jia, M.; Li, Q.; Meng, D. Bach1: Function, Regulation, and Involvement in Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 1347969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NandyMazumdar, M.; Paranjapye, A.; Browne, J.; Yin, S.; Leir, S.H.; Harris, A. BACH1, the master regulator of oxidative stress, has a dual effect on CFTR expression. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 3741–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welham, A.; Chorvinsky, E.; Bhattacharya, S.; Salka, K.; Bera, B.S.; Admasu, W.; Straker, M.C.; Gutierrez, M.J.; Jaiswal, J.K.; Nino, G. Impaired airway epithelial miR-155/BACH1/NRF2 axis and hypoxia gene expression during RSV infection in children with down syndrome. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1553571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozen, M.; Cokugras, H.; Ozen, N.; Camcioglu, Y.; Akcakaya, N. Relation between serum Insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 levels, clinical status and growth parameters in prepubertal cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr. Int. 2004, 46, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogan, M.P.; Reznikov, L.R.; Pezzulo, A.A.; Gansemer, N.D.; Samuel, M.; Prather, R.S.; Zabner, J.; Fredericks, D.C.; McCray, P.B., Jr.; Welsh, M.J.; et al. Pigs and humans with cystic fibrosis have reduced insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) levels at birth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20571–20575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ideozu, J.E.; Zhang, X.; Rangaraj, V.; McColley, S.; Levy, H. Microarray profiling identifies extracellular circulating miRNAs dysregulated in cystic fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, C.; McKiernan, P.J.; Raoof, R.; Henshall, D.C.; Linnane, B.; McNally, P.; Glasgow, A.M.A.; Greene, C.M. Plasma microRNA levels in male and female children with cystic fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowiak, Z.; Wojsyk-Banaszak, I.; Jonczyk-Potoczna, K.; Narozna, B.; Langwinski, W.; Szczepankiewicz, A. Extracellular vesicles-derived miRNAs as mediators of pulmonary exacerbation in pediatric cystic fibrosis. J. Breath Res. 2023, 17, 026005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abinesh, R.S.; Madhav, R.; Meghana, G.S.; Akhila, A.R.; Balamuralidhara, V. Precision medicine advances in cystic fibrosis: Exploring genetic pathways for targeted therapies. Life Sci. 2024, 358, 123186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweezey, N.B.; Ratjen, F. The cystic fibrosis gender gap: Potential roles of estrogen. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2014, 49, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gioia, S.; Daniello, V.; Conese, M. Extracellular Vesicles’ Role in the Pathophysiology and as Biomarkers in Cystic Fibrosis and COPD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilyazova, I.; Asadullina, D.; Kagirova, E.; Sikka, R.; Mustafin, A.; Ivanova, E.; Bakhtiyarova, K.; Gilyazova, G.; Gupta, S.; Khusnutdinova, E.; et al. MiRNA-146a-A Key Player in Immunity and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Yang, L.; Yuan, X. Roles of Exosomal miRNAs in Asthma: Mechanisms and Applications. J. Asthma Allergy 2024, 17, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Berg, N.; Lee, J.W.; Le, T.T.; Neudecker, V.; Jing, N.; Eltzschig, H. MicroRNA miR-223 as regulator of innate immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018, 104, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neudecker, V.; Brodsky, K.S.; Clambey, E.T.; Schmidt, E.P.; Packard, T.A.; Davenport, B.; Standiford, T.J.; Weng, T.; Fletcher, A.A.; Barthel, L.; et al. Neutrophil transfer of miR-223 to lung epithelial cells dampens acute lung injury in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaah5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodlie, M.; Haq, I.J.; Roberts, K.; Elborn, J.S. Targeted therapies to improve CFTR function in cystic fibrosis. Genome Med. 2015, 7, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| miRNA Levels Found in CF | Model | Molecular Target | Signal Pathways | Cytokines/Chemokines | Effect on Inflammation (I)/Wound Healing (WH) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

↑miR-155 | IB3-1 cells | ↓SHIP1 | ↑PI3K/Akt and MAPK | ↑IL-8 | ↑I | [77] |

↑miR-636 | CF primary bronchial cells | ↓IL-1R1, IKK-β, RANK | ↓NF-κB | ↓IL-8, IL-6 | ↓I | [78,79] |

| ↑miR-181a-5p | CF ALI cultures of AECs from bronchial brushings, nasal brushings, and nasal polyps | ↓IGF1 and WISP1 | PI3K–Akt deregulation | ND | ↓WH | [80] |

| ↓miR-126 | CF bronchial brushings, CF immortalised AECs | ↑TOM1 and Tollip | ↓NF-κB | ↓IL-8 | ↓I | [81] |

| ↓miR-17 | CF bronchial brushings, CF immortalised AECs | ND | ND | ↓IL-8 | ↓I | [82] |

| ↓miR-199a-3p | CF bronchial explants, CF primary bronchial AECs, CFBE41o− cell line | ↑IKK-β | ↑NF-κB | ↑IL-8 | ↑I | [78] |

| miR-93 ↓upon infection | CF immortalised cell lines IB3-1 and CuFi-1 | ND | ND | ↑IL-8 | ↑I | [83] |

| Study | Method | Cell Line/Cell Culture | Results | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oglesby et al., 2010 [81] | qRT-PCR and miRNA expression profiling | CF and non-CF bronchial brushings utilised for miRNA profiling | Of the 667 different miRNAs investigated, 93 were found differently expressed in CF patients as compared to controls, 56 were downregulated, while 36 were upregulated, in at least 3 CF patients. miRNA-126 was downregulated in 4 out of 5 CF patients, acting as a proinflammatory agent to increase its target gene TOM1 expression | This study showed that miR-126 is the key regulated miRNA in CF, whose low expression increases the TOM1 level, contributing to innate immune response and proinflammatory characteristics of CF |

| Catellani et al., 2022 [152] | Microarray expression profiling | Immortalised CF AECs CFBE41o- and 1B3-1, immortalised non-CF AECs 16HBE14o- | Among the 511 target genes of 41 dysregulated miRNAs, the authors evidenced IL-11, IL6R, and IL-18 genes, which are related to lung and airway epithelia. Five miRNAs were upregulated (miR-155-5p, miR-370-3p, miR-886-5p, miR-10b-3p, and miR-577-5p) and one miRNA (miR-1257) was downregulated in both CFBE41o- and IB3-1 cells | Malfunction of CFTR ascribed to the disruption in miRNA expression that contributes to dysregulated biological processes and airway inflammation |

| Pommier et al., 2021 [80] | Small RNA sequencing | ALI-polyps (CF vs. NCF); ALI-nasal (CF vs. NCF); ALI-bronchial cells (CF vs. NCF); immortalised CF AECs CFBE41o-, immortalised non-CF AECs BEAS-2B and 16HBE14o- | Three ex vivo models were analysed compared to the control for deregulated miRNA expression, with the results demonstrating upregulated miR-181a-5p and members of the miR-449 family. Sequence variants of miR-101-3p, along with miR-181a-5p, directly impact the regulation of WISP1, which causes cell proliferation, migration, and wound healing | Airway epithelia of CF patients have altered miRNAs, including isomiRNAs, that are likely related to disease-relevant phenotypes by modulating their target WISP1. The study identifies the mechanistic link between CFTR dysfunction and aberrant wound healing, proposing a new therapeutic target |

| De Santi et al., 2020 [153] | miRNA sequencing and miRNA profiling | CFBE41o- cell line transfected with wild-type or F508del-CFTR Primary BECs obtained from CF and non-CF subjects, purified and used for miRNA profiling | Several miRNAs (e.g., miR-145-5p, miR-223, miR-494, and miR-509-3p) were overexpressed in AECs of CF patients that bind to the CFTR- UTR3′ region, resulting in suppression of CFTR mRNA and protein levels. miR-223-3p and miR-509-3p were significantly increased in the ALI culture of CFBE41o- cells stably transfected with F508del versus wild-type CFTR | Specific target site blockers of the CFTR 3′ untranslated region were used to reverse miRNA-mediated inhibition of CFTR. This study suggests a new therapeutic approach of using mRNA–miRNA interaction to increase the CFTR expression |

| Study | Biological Fluid | CF patients | Method | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideozu et al. [165] | Plasma | Discovery phase, 5 CF patients (16.6 ± 4.8 years) and 5 HC (23 ± 1.6 years). Validation phase, 5 patients (22.3 ± 4.4 years) and 5 healthy controls (22.6 ± 3.5 years). | miRNA microarray profiling | Eleven miRNAs differentially expressed between CF and HC samples. The overexpressed miRNAs included hsa-miR-486-5p, 3 family members of let-7 (hsa-let-7b-5p, hsa-let-7c-5p, and hsa-let-7d-5p), hsa-miR-103a-3p, and other miRNAs, while hsa-miR-598-3p was underexpressed in CF |

| Mooney et al. [166] | Plasma | Six males and six females (age range: 1–6 years, median age: 3.8 years) | miRNA microarray profiling | Two significantly differentially regulated miRNAs in male versus female samples, miR-885-5p and miR-193a-5p |

| Stachowiak et al. [167] | EVs in sputum, exhaled breath condensate, and serum | Eight paediatric patients during pulmonary exacerbation and seven stable, aged 6–8 years | miRNA profiling by next-generation sequencing | The four miRNAs with the greatest fold-change between stable and exacerbation in sputum and serum (let-7c, miR-16, miR-25-3p, and miR-146a) were selected for validation. A panel of all four miRNAs in serum was the best predictive model of exacerbation, with miR-146a improving the predictive model of C-reactive protein and neutrophilia. Expression of airway miR-25-3p improved the diagnostic value of FEV1% predicted and FVC% predicted |

| miRNAs Found | AECs | Monocytes/Macrophages | Neutrophils | Extracellular Circulating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-155-5p | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| miR-636 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| miR-181a-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-126-3p | ✓ | |||

| miR-17 | ✓ | |||

| miR-199a-3p | ✓ | |||

| miR-93 | ✓ | |||

| miR-101-3p | ✓ | |||

| miR-199a-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-146a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| miR-224-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-452-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-223-3p | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| miR-106a-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-221-3p | ✓ | |||

| miR-370-3p | ✓ | |||

| miR-886-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-10b-3p | ✓ | |||

| miR-577-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-1257 | ✓ | |||

| miR-449 | ✓ | |||

| miR-145-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-494 | ✓ | |||

| miR-509-3p | ||||

| miR-885-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-486-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-193a-5p | ✓ | |||

| let-7b-5p | ✓ | |||

| let-7c-5p | ✓ | |||

| let-7d-5p | ✓ | |||

| miR-103a-3p | ✓ | |||

| miR-598-3p | ✓ | |||

| miR-16 | ✓ | |||

| miR-25-3p | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Carbone, A.; Sajid, N.; Soccio, P.; Tondo, P.; Lacedonia, D.; Di Gioia, S.; Conese, M. The Involvement of MicroRNAs in Innate Immunity and Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease: A Narrative Review. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010058

Carbone A, Sajid N, Soccio P, Tondo P, Lacedonia D, Di Gioia S, Conese M. The Involvement of MicroRNAs in Innate Immunity and Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease: A Narrative Review. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarbone, Annalucia, Namra Sajid, Piera Soccio, Pasquale Tondo, Donato Lacedonia, Sante Di Gioia, and Massimo Conese. 2026. "The Involvement of MicroRNAs in Innate Immunity and Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease: A Narrative Review" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010058

APA StyleCarbone, A., Sajid, N., Soccio, P., Tondo, P., Lacedonia, D., Di Gioia, S., & Conese, M. (2026). The Involvement of MicroRNAs in Innate Immunity and Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease: A Narrative Review. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010058