The MALDI Method to Analyze the Lipid Profile, Including Cholesterol, Triglycerides and Other Lipids

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of the Lipid Profile and Its Importance in Biology and Medicine

1.2. Basic Lipid Classes: Sterols, Triglycerides, Phospholipids, Sphingolipids, Free Fatty Acids

1.3. Traditional Lipid Analysis Methods (LC–MS, GC–MS, Enzymatic Assays)—Limitations

1.4. The Growing Importance of MALDI-MS in Lipidomics

1.5. Purpose and Scope of the Review

1.6. Literature Search Methodology

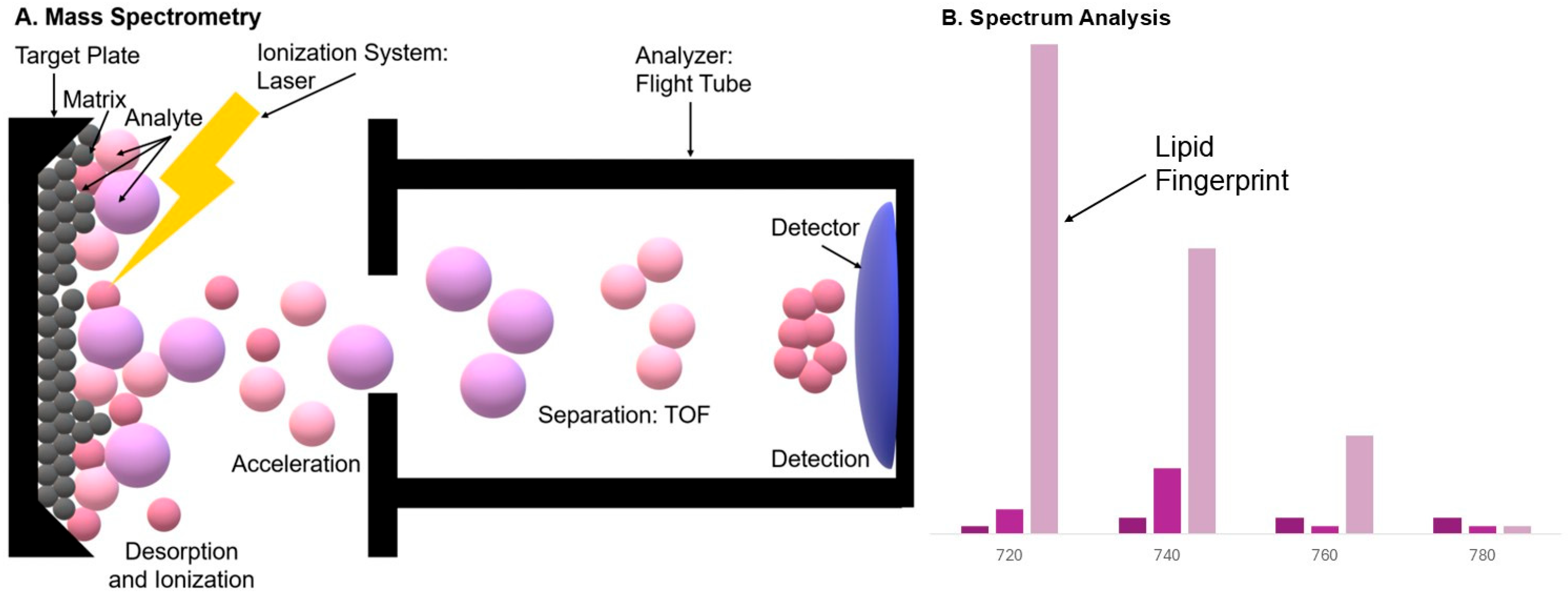

2. Theoretical Foundations of MALDI-MS

2.1. History and Development of the MALDI

2.2. Ionization Mechanism in MALDI

2.3. Most Commonly Used Matrices in Lipid Analysis

2.4. MALDI-Compatible Mass Analyzers

2.5. Influence of Selected Experimental Parameters on the Quality of Lipid Spectra

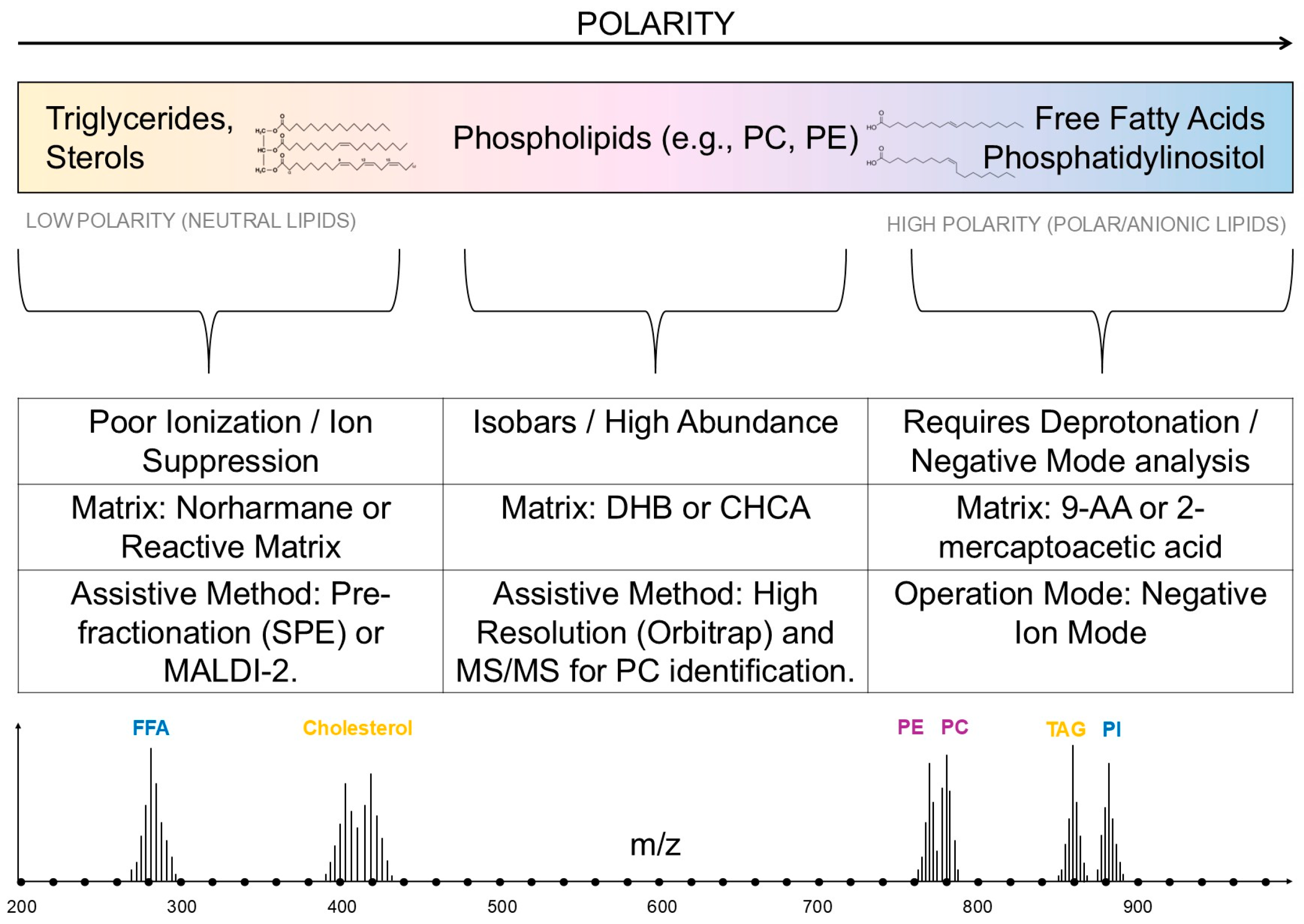

3. MALDI in the Analysis of Specific Lipid Classes

3.1. Analysis of Sterols, Including Cholesterol

3.2. Triglyceride (TAG) Analysis

3.3. Phospholipids

3.4. Sphingolipids

3.5. Other Lipid Classes

4. MALDI Imaging (MALDI-MSI) in Lipid Analysis

4.1. Principles of MALDI Lipid Imaging

4.2. Applications in Tissue Studies

4.3. Imaging Cholesterol and Phospholipids

4.4. Clinical and Preclinical Applications

4.5. Limitations and Challenges of Imaging Methods

5. Comparison of MALDI-MS with Other Lipidomics Techniques

5.1. MALDI vs. ESI-MS

5.2. MALDI vs. Ambient and High-Throughput Technologies (DESI, MALDESI, AEMS)

5.3. MALDI vs. LC–MS/GC–MS

5.4. Sensitivity, Selectivity, Repeatability

5.5. Advantages and Limitations of MALDI in the Context of Lipidomics

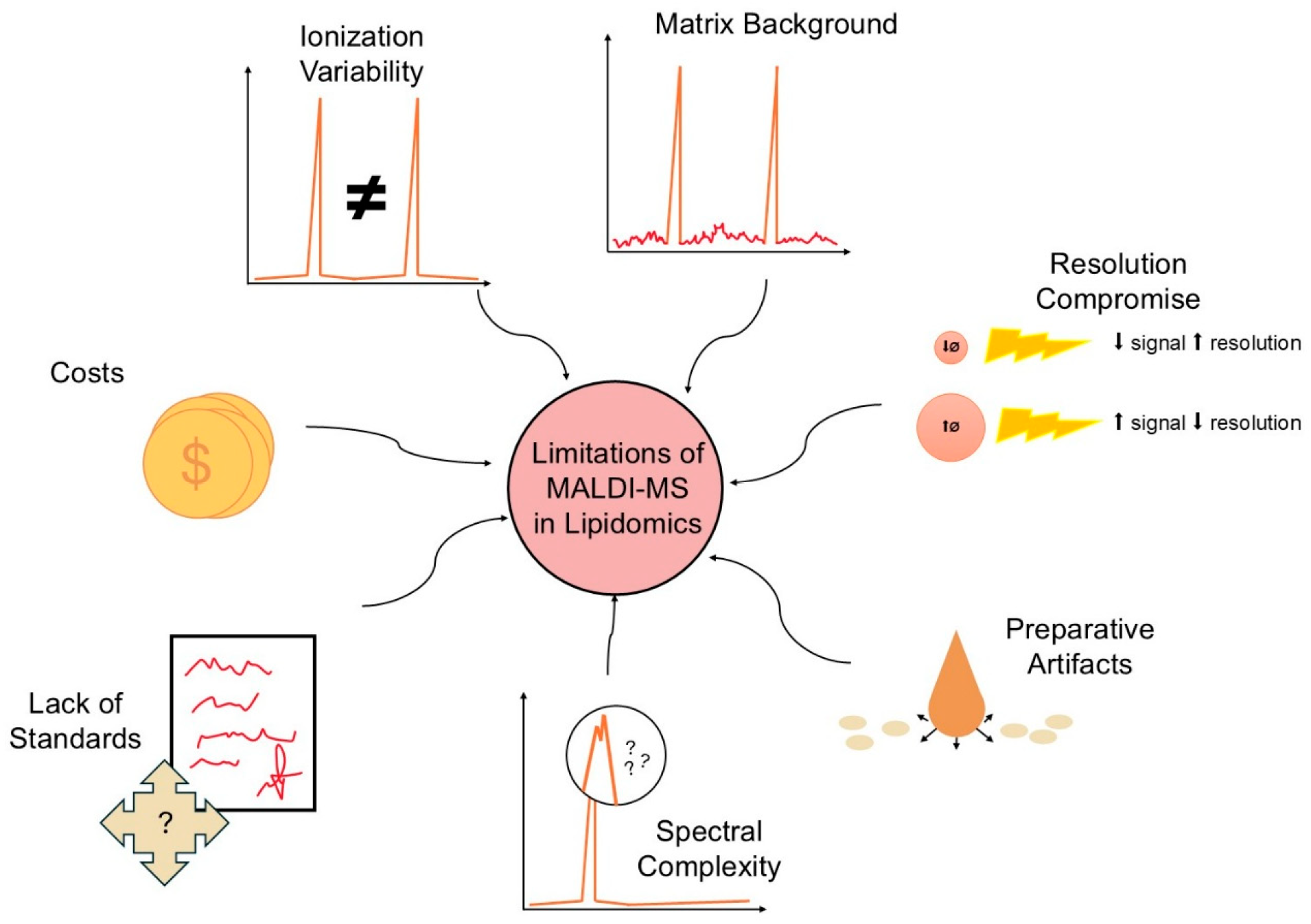

6. Factors Affecting the Reliability of MALDI Lipid Analysis

6.1. Ion Suppression and Artifacts

6.2. Influence of Matrix and Sample Application Method

6.3. Lipid Stability and Process-Based Degradation

6.4. Methodological Validation and Reproducibility

6.5. Standardization—The Biggest Challenge in MALDI Lipidomics

7. Current Development Directions of MALDI Technology in Lipidomics

7.1. Matrix-Free Matrices and Laser Ionization in LDI

7.2. Nanomaterials and Hybrid MALDI Matrices

7.3. Integrating MALDI with Microfluidics

7.4. MALDI-MS for Rapid Clinical Diagnostics

7.5. Automation and High-Throughput Lipid Analysis

7.6. Combining MALDI with AI/Machine Learning in Spectral Interpretation

8. Clinical Applications of MALDI Lipid Analysis

8.1. Metabolic Diseases (Diabetes, NAFLD, Obesity)

8.2. Neurodegenerative Diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s)

8.3. Lipid Profile in Oncology

8.4. Applications in Cardiology (Dyslipidemia, Atherosclerosis)

8.5. Possibilities of Using MALDI as an In Vivo/Ex Vivo Diagnostic Tool

9. Limitations of the Method and Unresolved Problems

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Addepalli, R.V.; Mullangi, R. A concise review on lipidomics analysis in biological samples. ADMET DMPK 2020, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornemann, T. Lipidomics in Biomarker Research. In Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerosis: Improving State-of-the-Art Management and Search for Novel Targets; Von Eckardstein, A., Binder, C.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Köfeler, H.C.; Fauland, A.; Rechberger, G.N.; Trötzmüller, M. Mass spectrometry based lipidomics: An overview of technological platforms. Metabolites 2012, 2, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardtova, I.; Jankech, T.; Majerova, P.; Piestansky, J.; Olesova, D.; Kovac, A.; Jampilek, J. Recent Analytical Methodologies in Lipid Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.; Suss, R.; Fuchs, B.; Muller, M.; Zschornig, O.; Arnold, K. MALDI-TOF MS in lipidomics. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 2568–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna, J.; García-Seisdedos, D.; Alcázar, A.; Lasunción, M.Á.; Busto, R.; Pastor, Ó. Quantitative lipidomic analysis of plasma and plasma lipoproteins using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2015, 189, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedusi, V. Lipidomics. Mater Methods 2018, 8, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Han, X. Lipidomics: Techniques, Applications, and Outcomes Related to Biomedical Sciences. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajka, T.; Fiehn, O. Comprehensive analysis of lipids in biological systems by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Trends Anal. Chem. 2014, 61, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Khalil, M.; Hou, W.; Zhou, H.; Elisma, F.; Swayne, L.A.; Blanchard, A.P.; Yao, Z.; Bennett, S.A.L.; Figeys, D. Lipidomics era: Accomplishments and challenges. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2010, 29, 877–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurowski, K.; Kochan, K.; Walczak, J.; Barańska, M.; Piekoszewski, W.; Buszewski, B. Analytical Techniques in Lipidomics: State of the Art. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2017, 47, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, K.M.; Prabutzki, P.; Leopold, J.; Nimptsch, A.; Lemmnitzer, K.; Vos, D.R.N.; Hopf, C.; Schiller, J. A new update of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in lipid research. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillen, J.C.; Fincher, J.A.; Klein, D.R.; Spraggins, J.M.; Caprioli, R.M. Effect of MALDI matrices on lipid analyses of biological tissues using MALDI-2 postionization mass spectrometry. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2020, 55, e4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, T.G.; Huynh, K.; Giles, C.; Meikle, P.J. Clinical lipidomics: Realizing the potential of lipid profiling. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarska, A.; Wąsowicz, W.; Gromadzińska, J. Lipidomic profiles as a tool to search for new biomarkers. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2022, 35, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadi, A.; Tsivelekidou, E.; Dermitzakis, I.; Theotokis, P.; Gargani, S.; Meditskou, S.; Manthou, M.E. Innovations in MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: Bridging modern diagnostics and historical insights. Open Life Sci. 2025, 20, 20251136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K. The origin of macromolecule ionization by laser irradiation (Nobel lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2003, 42, 3860–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.H.; Wang, Y.S. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry: Mechanistic Studies and Methods for Improving the Structural Identification of Carbohydrates. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 6, S0072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, D. Advances in the Mechanistic Understanding of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization In-Source Decay Mass Spectrometry for Peptides and Proteins: Electron Transfer Reaction as the Initiating Step of Fragmentation. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, J.; Prabutzki, P.; Engel, K.M.; Schiller, J. A Five-Year Update on Matrix Compounds for MALDI-MS Analysis of Lipids. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, J.; Popkova, Y.; Engel, K.M.; Schiller, J. Recent Developments of Useful MALDI Matrices for the Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Lipids. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angerer, T.B.; Bour, J.; Biagi, J.L.; Moskovets, E.; Frache, G. Evaluation of 6 MALDI-Matrices for 10 μm Lipid Imaging and On-Tissue MSn with AP-MALDI-Orbitrap. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 33, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J.; Flinders, B.; Cappell, J.; Liang, T.; Pelc, R.S.; Tran, B.; Kilgour, D.P.; Heeren, R.M.; Goodlett, D.R.; Ernst, R.K. Norharmane Matrix Enhances Detection of Endotoxin by MALDI-MS for Simultaneous Profiling of Pathogen, Host, and Vector Systems. Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, ftw097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLaney, K.; Phetsanthad, A.; Li, L. ADVANCES IN HIGH-RESOLUTION MALDI MASS SPECTROMETRY FOR NEUROBIOLOGY. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2022, 41, 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, D.; Powers, R. Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry Applications for Metabolomics. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietschel, B.; Baeumlisberger, D.; Arrey, T.N.; Bornemann, S.; Rohmer, M.; Schuerken, M.; Karas, M.; Meyer, B. The benefit of combining nLC-MALDI-Orbitrap MS data with nLC-MALDI-TOF/TOF data for proteomic analyses employing elastase. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 5317–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.F.; Aizikov, K.; Duursma, M.C.; Giskes, F.; Spaanderman, D.J.; McDonnell, L.A.; O’Connor, P.B.; Heeren, R.M. An external matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization source for flexible FT-ICR Mass spectrometry imaging with internal calibration on adjacent samples. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 22, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, F.; Hummon, A.B. Considerations for MALDI-Based Quantitative Mass Spectrometry Imaging Studies. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 3620–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, Y.; Miura, D. MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging for Visualizing In Situ Metabolism of Endogenous Metabolites and Dietary Phytochemicals. Metabolites 2014, 4, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treu, A.; Römpp, A. Matrix ions as internal standard for high mass accuracy matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 35, e9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chang, Z.; Deng, K.; Gu, J.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Luo, Q. Reactive Matrices for MALDI-MS of Cholesterol. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 16786–16790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Xu, L. MALDI-IM-MS Imaging of Brain Sterols and Lipids in a Mouse Model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bien, T.; Hambleton, E.A.; Dreisewerd, K.; Soltwisch, J. Molecular insights into symbiosis—Mapping sterols in a marine flatworm-algae-system using high spatial resolution MALDI-2-MS imaging with ion mobility separation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 413, 2767–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Lissel, F. MALDI Matrices for the Analysis of Low Molecular Weight Compounds: Rational Design, Challenges and Perspectives. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincher, J.A.; Korte, A.R.; Dyer, J.E.; Yadavilli, S.; Morris, N.J.; Jones, D.R.; Shanmugam, V.K.; Pirlo, R.K.; Vertes, A. Mass spectrometry imaging of triglycerides in biological tissues by laser desorption ionization from silicon nanopost arrays. J. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 55, e4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, B.; Gidden, J.; Lay, J.O., Jr.; Durham, B. A rapid separation technique for overcoming suppression of triacylglycerols by phosphatidylcholine using MALDI-TOF MS. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2428–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, P.; Tilahun, E.; Breivik, J.F.; Abdulkader, B.M.; Frøyland, L.; Zeng, Y. A simple liquid extraction protocol for overcoming the ion suppression of triacylglycerols by phospholipids in liquid chromatography mass spectrometry studies. Talanta 2016, 148, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparvero, L.J.; Amoscato, A.A.; Dixon, C.E.; Long, J.B.; Kochanek, P.M.; Pitt, B.R.; Bayir, H.; Kagan, V.E. Mapping of phospholipids by MALDI imaging (MALDI-MSI): Realities and expectations. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2012, 165, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, J.; Süss, R.; Arnhold, J.; Fuchs, B.; Lessig, J.; Müller, M.; Petković, M.; Spalteholz, H.; Zschörnig, O.; Arnold, K. Matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry in lipid and phospholipid research. Prog. Lipid Res. 2004, 43, 449–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, B.; Schiller, J. MALDI-TOF MS analysis of lipids from cells, tissues and body fluids. Subcell. Biochem. 2008, 49, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.E.; Dworski, S.; Canals, D.; Casas, J.; Fabrias, G.; Schoenling, D.; Levade, T.; Denlinger, C.; Hannun, Y.A.; Medin, J.A.; et al. On-tissue localization of ceramides and other sphingolipids by MALDI mass spectrometry imaging. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 8303–8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Tang, C.; Wu, J.X.; Ji, B.W.; Gong, B.M.; Wu, X.H.; Wang, X. Mass Spectrometry Detects Sphingolipid Metabolites for Discovery of New Strategy for Cancer Therapy from the Aspect of Programmed Cell Death. Metabolites 2023, 13, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Lee, S.C.; Park, Y.S.; Jeon, Y.E.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, S.-Y.; Park, I.H.; Jang, S.H.; Park, H.M.; Yoo, C.W.; et al. Protein and lipid MALDI profiles classify breast cancers according to the intrinsic subtype. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Savas, J.N.; Hanrieder, J. Spatial neurolipidomics-MALDI mass spectrometry imaging of lipids in brain pathologies. J. Mass Spectrom. 2024, 59, e5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, H. Improved MALDI imaging MS analysis of phospholipids using graphene oxide as new matrix. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solntceva, V.; Kostrzewa, M.; Larrouy-Maumus, G. Detection of Species-Specific Lipids by Routine MALDI TOF Mass Spectrometry to Unlock the Challenges of Microbial Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 621452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Jiang, Z.H.; Chiou, S.F.; Shiea, J.; Wu, D.C.; Tseng, S.P.; Jain, S.H.; Chang, C.Y.; Lu, P.L. Rapid Characterization of Bacterial Lipids with Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry for Species Differentiation. Molecules 2022, 27, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaisinghani, N.; Seeliger, J.C. Recent advances in the mass spectrometric profiling of bacterial lipids. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2021, 65, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichler, M.; Walch, A. MALDI Imaging mass spectrometry: Current frontiers and perspectives in pathology research and practice. Lab. Investig. 2015, 95, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xu, T.; Peng, C.; Wu, S. Advances in MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging Single Cell and Tissues. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 782432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barré, F.P.Y.; Paine, M.R.L.; Flinders, B.; Trevitt, A.J.; Kelly, P.D.; Ait-Belkacem, R.; Garcia, J.P.; Creemers, L.B.; Stauber, J.; Vreeken, R.J.; et al. Enhanced Sensitivity Using MALDI Imaging Coupled with Laser Postionization (MALDI-2) for Pharmaceutical Research. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 10840–10848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Oh, J.Y.; Lee, K.S.; Lim, H.K.; Lee, J.; Yoon, H.R.; Jung, J. Lipid Profiles Obtained from MALDI Mass Spectrometric Imaging in Liver Cancer Metastasis Model. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2022, 2022, 6007158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, A.P.; Bogie, J.F.J.; Hendriks, J.J.A.; Haidar, M.; Belov, M.; Heeren, R.M.A.; Ellis, S.R. Evaluation of lipid coverage and high spatial resolution MALDI-imaging capabilities of oversampling combined with laser post-ionisation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 2277–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Justin Raj, D.R.; Aebisher, D. Detection of Protein and Metabolites in Cancer Analyses by MALDI 2000–2025. Cancers 2025, 17, 3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuck, M.; Grélard, F.; Blanc, L.; Desbenoit, N. MALDI-MSI Towards Multimodal Imaging: Challenges and Perspectives. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 904688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, I.; Maimó-Barceló, A.; Garate, J.; Bestard-Escalas, J.; Scrimini, S.; Sauleda, J.; Cosío, B.G.; Fernández, J.A.; Barceló-Coblijn, G. Challenges and Advantages of Using Spatially Resolved Lipidomics to Assess the Pathological State of Human Lung Tissue. Cancers 2025, 17, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, W.M.; Waidelich, D.; Kerner, A.; Hanke, S.; Berg, R.; Trumpp, A.; Rösli, C. MALDI versus ESI: The Impact of the Ion Source on Peptide Identification. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.J.; Pu, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Tang, D.; Dai, Y. Comparing DESI-MSI and MALDI-MSI Mediated Spatial Metabolomics and Their Applications in Cancer Studies. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 891018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slijkhuis, N.; Towers, M.; Claude, E.; van Soest, G. MALDI versus DESI mass spectrometry imaging of lipids in atherosclerotic plaque. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 39, e9927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlin, L.S.; Liu, X.; Ferreira, C.R.; Santagata, S.; Agar, N.Y.; Cooks, R.G. Desorption electrospray ionization then MALDI mass spectrometry imaging of lipid and protein distributions in single tissue sections. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 8366–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Tu, A.; Muddiman, D.C. Lipidomic profiling of single mammalian cells by infrared matrix-assisted laser desorption electrospray ionization (IR-MALDESI). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 8211–8222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Mei, P.C.; Li, A.; Fu, X.F.; Wu, X.Z.; Jiang, H.P.; Zhu, Q.F.; Feng, Y.Q. Derivatization-Assisted Acoustic Ejection Mass Spectrometry for High-Throughput FAHFA Prescreening. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 9613–9619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Shon, J.C.; Liu, K.H. Mass Spectrometry-based Lipidomics and Its Application to Biomedical Research. J. Lifestyle Med. 2014, 4, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Llamero, C.; García-García, P.; Señoráns, F.J. Efficient Green Extraction of Nutraceutical Compounds from Nannochloropsis gaditana: A Comparative Electrospray Ionization LC-MS and GC-MS Analysis for Lipid Profiling. Foods 2024, 13, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Howe, K.; Wilson, D.B.; Moser, F.; Irwin, D.; Thannhauser, T.W. A comparison of nLC-ESI-MS/MS and nLC-MALDI-MS/MS for GeLC-based protein identification and iTRAQ-based shotgun quantitative proteomics. J. Biomol. Tech. 2007, 18, 226–237. [Google Scholar]

- Züllig, T.; Trötzmüller, M.; Köfeler, H.C. Lipidomics from sample preparation to data analysis: A primer. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, P.M.; Spraggins, J.M.; Baldwin, H.S.; Caprioli, R. Enhanced sensitivity for high spatial resolution lipid analysis by negative ion mode matrix assisted laser desorption ionization imaging mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, K.R.; Dufresne, M.; Colley, M.E.; Migas, L.G.; Van de Plas, R.; Spraggins, J.M. High-Specificity and Sensitivity Imaging of Neutral Lipids Using Salt-Enhanced MALDI TIMS. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 2213–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cao, Q.; Liu, Y.; DeLaney, K.; Tian, Z.; Moskovets, E.; Li, L. Characterizing and alleviating ion suppression effects in atmospheric pressure matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 33, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Han, X. Enhanced coverage of lipid analysis and imaging by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry via a strategy with an optimized mixture of matrices. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1000, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; de Waal, B.F.; Milroy, L.G.; van Dongen, J.L. A sample preparation method for recovering suppressed analyte ions in MALDI TOF MS. J. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 50, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemperline, E.; Rawson, S.; Li, L. Optimization and comparison of multiple MALDI matrix application methods for small molecule mass spectrometric imaging. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 10030–10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielczarek, P.; Suder, P.; Kret, P.; Słowik, T.; Gibuła-Tarłowska, E.; Kotlińska, J.H.; Kotsan, I.; Bodzon-Kulakowska, A. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging sample preparation using wet-interface matrix deposition for lipid analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 37, e9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, C.Z.; Koelmel, J.P.; Jones, C.M.; Garrett, T.J.; Aristizabal-Henao, J.J.; Vesper, H.W.; Bowden, J.A. A Review of Efforts to Improve Lipid Stability during Sample Preparation and Standardization Efforts to Ensure Accuracy in the Reporting of Lipid Measurements. Lipids 2021, 56, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, N.H.; Thomas, A.; Chaurand, P. Monitoring time-dependent degradation of phospholipids in sectioned tissues by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 49, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakh, I.; Sledzinski, T.; Kaska, L.; Mozolewska, P.; Mika, A. Sample Preparation Methods for Lipidomics Approaches Used in Studies of Obesity. Molecules 2020, 25, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiersbrock, F.B.; Orthen, J.M.; Soltwisch, J. Validation of MALDI-MS imaging data of selected membrane lipids in murine brain with and without laser postionization by quantitative nano-HPLC-MS using laser microdissection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 6875–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquer, G.; Sementé, L.; Ràfols, P.; Martín-Saiz, L.; Bookmeyer, C.; Fernández, J.A.; Correig, X.; García-Altares, M. rMSIfragment: Improving MALDI-MSI lipidomics through automated in-source fragment annotation. J. Cheminform. 2023, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, G.; Bianco, M.; Losito, I.; Cataldi, T.R.I.; Calvano, C.D. MALDI mass spectrometry imaging in plant and food lipidomics: Advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Mol. Omics 2025, 21, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, D.S. Matrix-free methods for laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2007, 26, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Knapp, D.R. Matrix-free LDI mass spectrometry platform using patterned nanostructured gold thin film. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 7772–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomastowski, P.; Buszewski, B. Complementarity of Matrix- and Nanostructure-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Approaches. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, H.N. Nanoparticle-based surface assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry: A review. Mikrochim. Acta 2019, 186, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Kwon, S.; Kim, Y.K. Graphene Oxide Derivatives and Their Nanohybrid Structures for Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Small Molecules. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.N.; Baldwin, K.; Muller, L.; Womack, V.M.; Schultz, J.A.; Balaban, C.; Woods, A.S. Imaging of lipids in rat heart by MALDI-MS with silver nanoparticles. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVoe, D.L.; Lee, C.S. Microfluidic technologies for MALDI-MS in proteomics. Electrophoresis 2006, 27, 3559–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.E.; Park, I.; Rubakhin, S.S.; Bashir, R.; Vlasov, Y.; Sweedler, J.V. Droplet Microfluidics with MALDI-MS Detection: The Effects of Oil Phases in GABA Analysis. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2021, 1, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesbah, K.; Thai, R.; Bregant, S.; Malloggi, F. DMF-MALDI: Droplet based microfluidic combined to MALDI-TOF for focused peptide detection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.W.; Nedelkov, D.; Walsh, R.; Hattan, S.J. Applications of MALDI Mass Spectrometry in Clinical Chemistry. Clin. Chem. 2016, 62, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderaro, A.; Chezzi, C. MALDI-TOF MS: A Reliable Tool in the Real Life of the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Chen, B.; Harradine, P.; Habulihaz, B.; McLaren, D.G.; Cancilla, M.T. Applying Automation and High-Throughput MALDI Mass Spectrometry for Peptide Metabolic Stability Screening. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 34, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas, M.E.; Peltier-Heap, R.E.; Leveridge, M.; Annan, R.S.; Büttner, F.H.; Trost, M. Advances in high-throughput mass spectrometry in drug discovery. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023, 15, e14850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, K.; Sweedler, J.V. Workflow for High-throughput Screening of Enzyme Mutant Libraries Using Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Escherichia coli Colonies. Bio Protoc. 2023, 13, e4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebal, U.W.; Phan, A.N.T.; Sudhakar, M.; Raman, K.; Blank, L.M. Machine Learning Applications for Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics. Metabolites 2020, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañé, H.; Baiges-Gaya, G.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Herrero, P.; Delpino-Rius, A.; Canela, N.; Menendez, J.A.; Camps, J.; et al. Coupling Machine Learning and Lipidomics as a Tool to Investigate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. A General Overview. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, A.; Wang, Y.S. Recent Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Related Technical Challenges in MALDI MS and MALDI-MSI: A Mini Review. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 14, A0175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ščupáková, K.; Soons, Z.; Ertaylan, G.; Pierzchalski, K.A.; Eijkel, G.B.; Ellis, S.R.; Greve, J.W.; Driessen, A.; Verheij, J.; De Kok, T.M.; et al. Spatial Systems Lipidomics Reveals Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Heterogeneity. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 5130–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markgraf, D.F.; Al-Hasani, H.; Lehr, S. Lipidomics-Reshaping the Analysis and Perception of Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; He, S.; Begum, M.M.; Han, X. Myelin Lipid Alterations in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Landscape and Pathogenic Implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2024, 41, 1073–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J. Recent Advances of MALDI-Mass Spectrometry Imaging in Cancer Research. Mass Spectrom. Lett. 2019, 10, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bookmeyer, C.H.M.; Correig, F.X.; Masana, L.; Magni, P.; Yanes, Ó.; Vinaixa, M. Advancing atherosclerosis research: The Power of lipid imaging with MALDI-MSI. Atherosclerosis 2025, 403, 119130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, F.; Bertagna, G.; Quercioli, L.; Pucci, A.; Rocchiccioli, S.; Ferrari, M.; Recchia, F.A.; McDonnell, L.A. Lipids associated with atherosclerotic plaque instability revealed by mass spectrometry imaging of human carotid arteries. Atherosclerosis 2024, 397, 118555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthoff, A.; Schwenzfeier, J.; Niehaus, M.; Bessler, S.; Hoffmann, E.; Soehnlein, O.; Höhndorf, J.; Dreisewerd, K.; Soltwisch, J. Spatial biology using single-cell mass spectrometry imaging and integrated microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Kaya, I.; Wik, E.; Baijnath, S.; Lodén, H.; Nilsson, A.; Zhang, X.; Sehlin, D.; Syvänen, S.; Svenningsson, P.; et al. Comprehensive Approach for Sequential MALDI-MSI Analysis of Lipids, N-Glycans, and Peptides in Fresh-Frozen Rodent Brain Tissues. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.F. Mass spectrometry-based shotgun lipidomics—A critical review from the technical point of view. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 6387–6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, B.; Süss, R.; Schiller, J. An update of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in lipid research. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010, 49, 450–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelmel, J.P.; Ulmer, C.Z.; Jones, C.M.; Yost, R.A.; Bowden, J.A. Common cases of improper lipid annotation using high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry data and corresponding limitations in biological interpretation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Cheng, S.; Yang, J.; Feng, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, Q.; Xia, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Ma, X. Large-scale lipid analysis with C=C location and sn-position isomer resolving power. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, B.M. An Analytical Evaluation of Tools for Lipid Isomer Differentiation in Imaging Mass Spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2024, 502, 117268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzlechner, M.; Eugenin, E.; Prideaux, B. Mass spectrometry imaging to detect lipid biomarkers and disease signatures in cancer. Cancer Rep. 2019, 2, e1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyanovsky, D.A.; Sparvero, L.J.; Amoscato, A.A.; He, R.R.; Watkins, S.; Pitt, B.R.; Bayir, H.; Kagan, V.E. Improved spatial resolution of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization imaging of lipids in the brain by alkylated derivatives of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 28, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizing, L.R.S.; Ellis, S.R.; Beulen, B.W.A.M.M.; Barré, F.P.Y.; Kwant, P.B.; Vreeken, R.J.; Heeren, R.M.A. Development and evaluation of matrix application techniques for high throughput mass spectrometry imaging of tissues in the clinic. Clin. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 12, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tressler, C.; Tilley, S.; Yang, E.; Donohue, C.; Barton, E.; Creissen, A.; Glunde, K. Factorial Design to Optimize Matrix Spraying Parameters for MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 32, 2728–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, T.S.; Kaakeh, R.; Nagel, J.L.; Newton, D.W.; Stevenson, J.G. Cost Analysis of Implementing Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry Plus Real-Time Antimicrobial Stewardship Intervention for Bloodstream Infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 55, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.; Alby, K.; Kerr, A.; Jones, M.; Gilligan, P.H. Cost Savings Realized by Implementation of Routine Microbiological Identification by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergrift, G.W.; Kew, W.; Andersen, A.; Lukowski, J.K.; Goo, Y.A.; Anderton, C.R. Experimental and Computational Evaluation of Lipidomic In-Source Fragmentation as a Result of Postionization with Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 16127–16133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasch, P.; Beyer, W.; Bosch, A.; Borriss, R.; Drevinek, M.; Dupke, S.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Gao, X.; Grunow, R.; Jacob, D.; et al. A MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry database for identification and classification of highly pathogenic bacteria. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figini, M.; De Francesco, V.; Finato, N.; Errichetti, E. Dermoscopy in adult colloid milium. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, e127–e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, S.; Pagel, E. Insights on next-generation manufacturing of smart devices using text analytics. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wang, J. The extended pluripotency protein interactome and its links to reprogramming. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2014, 28, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlgren, U.S.; Bennet, W. ABO-Incompatible Liver Transplantation—A Review of the Historical Background and Results. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 38, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.V.; Ulrich, J.; Costa, L.; Ribeiro, L.A. Multiple Primary Malignancies in Head and Neck Cancer: A University Hospital Experience Over a Five-Year Period. Cureus 2021, 13, e17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criterion | MALDI-MS [5,6,7] | LC–MS (ESI/APCI) [8,9] | GC–MS [10,11] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Required sample preparation | Minimal; often direct analysis or simple lipid extraction; requires matrix selection | Medium; requires extraction, sometimes purification, and chromatographic separation | High; requires extraction and mandatory derivatization (e.g., FAME) |

| Lipid range analyzed | Broad: phospholipids, sphingolipids, TAG, DAG, sterols; more difficult: FFA below low mass | Very broad, maximum versatility—virtually all lipid classes | Mainly FFA and sterols after derivatization; more difficult for phospholipids and sphingolipids |

| Sensitivity | High (matrix dependent); increases with MALDI-2 | Very high | Very high after derivatization |

| Isomer resolution | Limited (no chromatographic separation) | High thanks to chromatography | High for volatile derivatives |

| Analysis speed | Very fast (seconds per spectrum) | Average (minutes to hours per analysis) | Average |

| Imaging capability (MSI) | YES—unique advantage (MALDI-MSI enables lipid mapping in tissues) | No (no integration with additional techniques) | No |

| Instrument complexity and operating cost | Average | High | Average |

| Resistance to matrix contamination | High tolerance to salt, urea and pollutants | Low to medium (ion suppression) | Low (requires pure extracts) |

| Clinical/translational utility | High in the context of rapid analysis and tissue imaging; rising in biomarkers | Very high—the gold standard of clinical lipidomics | Limited mainly to fatty acid analysis |

| Typical applications | Tissue lipidomics, tumor imaging, TAG and sterol analysis; rapid clinical analysis | Lipidome profiling, disease biomarkers, mechanistic studies | FFA, sterol analysis, food quality control, reference methods |

| Categories | Advantages | Limitations | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Analysis | Rapid and direct analysis of extracts and tissues; minimal preparation required | Quantification difficulties and different ionization efficiency between lipid classes | [118] |

| Multi-dimensional Imaging (MALDI-MSI) | Ability to map lipid localization in tissue; integration with histology | Lipid delocalization, limited spatial resolution with high sensitivity | [119] |

| Lipid Detection Range | Possibility of ionization of various lipid classes (phospholipids, sphingolipids, neutral lipids) | Weak ionization of some lipids (e.g., TAG, sterols) | [120] |

| Performance and Throughput | Fast measurements and high throughput; automation possible | High equipment and operating costs; requires advanced sample preparation | [121] |

| Development Potential | Integration with ML/AI and other omics; development of new matrices and nanomaterials | Lack of interlaboratory standards, limited reproducibility between studies | [122] |

| Clinical Applications | The perspective of personalized diagnostics; complementing histology | Requires further validation, standardization and integration with clinical data | [114] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aebisher, D.; Rudy, I.; Rogóż, K.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. The MALDI Method to Analyze the Lipid Profile, Including Cholesterol, Triglycerides and Other Lipids. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010059

Aebisher D, Rudy I, Rogóż K, Bartusik-Aebisher D. The MALDI Method to Analyze the Lipid Profile, Including Cholesterol, Triglycerides and Other Lipids. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleAebisher, David, Izabela Rudy, Kacper Rogóż, and Dorota Bartusik-Aebisher. 2026. "The MALDI Method to Analyze the Lipid Profile, Including Cholesterol, Triglycerides and Other Lipids" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010059

APA StyleAebisher, D., Rudy, I., Rogóż, K., & Bartusik-Aebisher, D. (2026). The MALDI Method to Analyze the Lipid Profile, Including Cholesterol, Triglycerides and Other Lipids. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010059