Genomic Insights into Unspecified Monogenic Forms of Diabetes and Their Associated Comorbidities: Implication for Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The phenotypic overlap between MFD, T1D, and T2D;

- (2)

- The limited access to genetic testing and trained personnel;

- (3)

- The lack of awareness among healthcare providers;

- (4)

- The lack of standardized, easy-to-use screening tools in routine practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Sample Collection

- Inclusion criteria

- Exclusion criteria

2.2. Genomic Investigation

2.2.1. DNA Extraction

2.2.2. WES

2.2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.2.4. Sanger Sequencing

3. Results

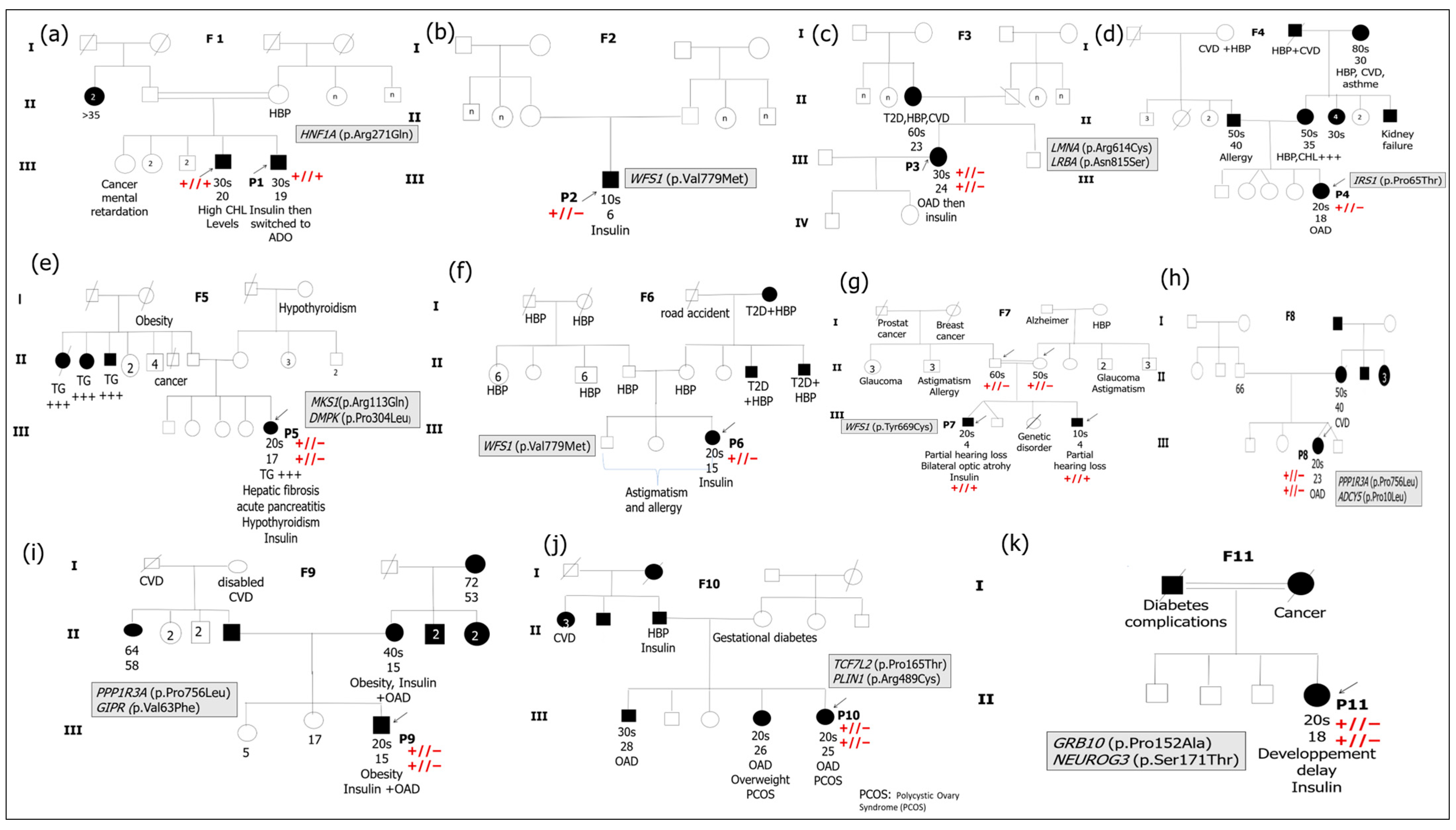

3.1. Cohort Study Description

3.2. Genetic Findings

| Patient ID | Gene & Exon | Refseq | Genetic Variant | Genotype | Consequence | dbSNP | gnomAD Frequency | Pathogenicity Score | References | Final Pathogenicity Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | HNF1A exon 4 | NM_000545.8 | c.812G>A | Hom | p.Arg271Gln | rs779184183 | 8.031 × 10−6 | 13 | Clin var (ID:449403) | Pathogenic |

| P2 | WFS1 exon 8 | NM_001145853.1 | c.2335G>A | Het | p.Val779Met | rs141328044 | 0.0017 | 11 | Uniprot/Clin Var (ID: 45453) | Pathogenic |

| P3 | LMNA exon 10 | NM_170708.4 | c.1840C>T | Het | p.Arg614Cys | rs142000963 | 0.0012 | 13 | The present study | Likely to be pathogenic |

| LRBA exon 20 | NM_001199282.2 | c.2444A>G | Het | p.Asn815Ser | rs140666848 | 0.0022 | 9 | ClinVar (ID: 218542) | Likely to be pathogenic | |

| P4 | IRS1 exon 1 | NM_005544.3 | c.193C>A | Het | p.Pro65Thr | rs149830479 | 8.774 × 10−5 | 8 | The present study | Likely to be pathogenic |

| P5 | MKS1 exon 4 | NM_001165927.1 | c.338G>A | Het | p.Arg113Gln | rs202112856 | 0.0004 | 8 | ClinVar (ID: 235814) ClinVar (ID:2440881) | Likely to be pathogenic |

| DMPK exon 7 | NM_001288765.1 | c.911C>T | Het | p.Pro304Leu | rs200491028 | 0.0002 | 8 | Likely to be pathogenic | ||

| P6 | WFS1 exon 8 | NM_001145853.1 | c.2335G>A | Het | p.Val779Met | rs141328044 | 0.0017 | 10 | Uniprot/Clin Var (ID: 45453) | Pathogenic |

| P7 | WFS1 exon 8 | NM_001145853.1 | c.2006A>G | Hom | p.Tyr669Cys | rs1402999203 | 3.987 × 10−6 | 14 | Uniprot/ClinVar (ID: 2576526) | Pathogenic |

| P8 | PPP1R3A exon 4 | NM_002711.4 | c.2267C>T | Het | p.Pro756Leu | rs151310594 | 0.0009 | 11 | ClinVar (ID: 393402) | Benign |

| ADCY5 exon 1 | NM_183357.3 | c.29C>T | Het | p.Pro10Leu | rs143905423 | 0.0012 | 11 | ClinVar (ID: 1170029) | Likely to be pathogenic | |

| P9 | PPP1R3A exon 4 | NM_002711.4 | c.2267C>T | Het | p.Pro756Leu | rs151310594 | 0.0009 | 11 | ClinVar (ID: 393402) | Benign |

| GIPR exon 4 | NM_001308418.2 | c.187G>T | Het | p.Val63Phe | rs142528936 | 5.171 × 10−6 | 14 | The present study | Likely to be pathogenic | |

| P10 | TCF7L2 exon 5 | NM_001146283.2 | c.493C>A | Het | p.Pro165Thr | - | - | 12 | The present study | Likely to be pathogenic |

| PLIN 1 exon 9 | NM_001145311.2 | c.1465C>T | Het | p.Arg489Cys | rs780710485 | 0.0002 | 8 | The present study | Likely to be pathogenic | |

| P11 | GRB 10 exon 4 | NM_001001549.3 | c.454C>G | Het | p.Pro152Ala | rs200175899 | 0.0008 | 10 | The present study | Likely to be pathogenic |

| NEUROG3 exon2 | NM_020999.4 | c.511T>A | Het | p.Ser171Thr | rs200417293 | 0.0004 | 9 | The present study | Likely to be pathogenic |

3.3. Classification and Management of MFD

4. Discussion

4.1. MFD: MODY & Syndromic Diabetes

4.2. Unspecified MFD

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IDF Diabetes Atlas 2025. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/idf-diabetes-atlas-2025/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45 (Suppl. 1), 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colclough, K.; Ellard, S.; Hattersley, A.; Patel, K. Syndromic Monogenic Diabetes Genes Should Be Tested in Patients with a Clinical Suspicion of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young. Diabetes 2022, 71, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, S.; Harvengta, A.; Gallo, P.; Martin, M.; Beckers, D.; Mouraux, T.; Seret, N.; Lebrethon, M.-C.; Helaers, R.; Brouillard, P.; et al. A New Tool to Identify Pediatric Patients with Atypical Diabetes Associated with Gene Polymorphisms. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemaa, R.; Razgallah, R.; Rais, L.; Ben Ghorbel, I.; Feki, M.; Kallel, A. Prevalence of diabetes in the Tunisian popula-tion: Results of the ATERA-survey. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. Suppl. 2022, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheriji, N.; Dallali, H.; Gouiza, I.; Hechmi, M.; Mahjoub, F.; Mrad, M.; Krir, A.; Soltani, M.; Trabelsi, H.; Hamdi, W.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals novel variants of monogenic diabetes in Tunisia: Impact on diagnosis and healthcare management. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1224284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.; Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaux, A.; Papadimitriou, S.; Versbraegen, N.; Nachtegael, C.; Boutry, S.; Nowé, A.; Smits, G.; Lenaerts, T. ORVAL: A novel platform for the prediction and exploration of disease-causing oligogenic variant combinations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W93–W98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, E.; Strihan, C.; Potievsky, O.; Nimri, R.; Shalitin, S.; Cohen, O.; Shehadeh, N.; Weintrob, N.; Phillip, M.; Gat-Yablonski, G. Four novel mutations, including the first gross deletion in TCF1, identified in HNF-4α, GCK and TCF1 in patients with MODY in Israel. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 20, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çubuk, H.; Çapan, Ö.Y. A Review of Functional Characterization of Single Amino Acid Change Mutations in HNF Transcription Factors in MODY Pathogenesis. Protein J. 2021, 40, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, L.; Li, M.; Leblicq, C.; Rafique, I.; Alarcon-Martinez, T.; Lange, C.; Rendon, L.; Tam, E.; Bouyonnec, A.C.-L.; Polychronakos, C. Monogenic Causes in the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium Cohort: Low Genetic Risk for Auto-immunity in Case Selection. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 1804–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raile, K.; Schober, E.; Konrad, K.; Thon, A.; Grulich-Henn, J.; Meissner, T.; Wölfle, J.; Scheuing, N.; Holl, R.W.; DPV Initiative the German BMBF Competence Network Diabetes Mellitus. Treatment of young patients with HNF1A mutations (HNF1A-MODY). Diabet. Med. 2015, 32, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, F.; Deng, X.; Yuan, L. Identification of the rare variant p.Val803Met of WFS1 gene as a cause of Wolfram-like syndrome in a Chinese family. Acta Diabetol. 2020, 57, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltoni, G.; Franceschi, R.; Di Natale, V.; Al-Qaisi, R.; Greco, V.; Bertorelli, R.; De Sanctis, V.; Quattrone, A.; Mantovani, V.; Cauvin, V.; et al. Next Generation Sequencing Analysis of MODY-X Patients: A Case Report Series. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gong, S.; Li, M.; Cai, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Ma, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. The genetic and clinical characteristics of WFS1 related diabetes in Chinese early onset type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutish, A.; Elmore, J.; Ilse, W.; Johnston, J.L.; Hittel, D.; Kerr, M.; Khan, A.; Rockman-Greenberg, C.; Mhanni, A.A.; Canadian Prairie Metabolic Network (CPMN). A novel WFS1 variant associated with isolated congenital cataracts. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2023, 9, a006259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Function, N. LMNA Gene. 2020; pp. 1–7. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Desgrouas, C.; Varlet, A.-A.; Dutour, A.; Galant, D.; Merono, F.; Bonello-Palot, N.; Bourgeois, P.; Lasbleiz, A.; Petitjean, C.; Ancel, P.; et al. Unraveling LMNA Mutations in Metabolic Syndrome: Cellular Phenotype and Clinical Pitfalls. Cells 2020, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florwick, A.; Dharmaraj, T.; Jurgens, J.; Valle, D.; Wilson, K.L. LMNA sequences of 60,706 unrelated individuals reveal 132 novel missense variants in A-type lamins and suggest a link between variant p.G602S and type 2 diabetes. Front. Genet. 2017, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Pombo, A.; Diaz-Lopez, E.J.; Castro, A.I.; Sanchez-Iglesias, S.; Cobelo-Gomez, S.; Prado-Moraña, T.; Araujo-Vilar, D. Clinical Spectrum of LMNA-Associated Type 2 Familial Partial Lipodystrophy: A Systemat-ic Review. Cells 2023, 12, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Herrera, G.; Tampella, G.; Pan-Hammarström, Q.; Herholz, P.; Trujillo-Vargas, C.M.; Phadwal, K.; Simon, A.K.; Moutschen, M.; Etzioni, A.; Mory, A.; et al. Deleterious mutations in LRBA are associated with a syndrome of immune deficiency and au-toimmunity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 986–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappalardo, M.A.; Russo, G.T.; Pedone, A.; Pizzo, A.; Borrielli, I.; Stabile, G.; Artenisio, A.C.; Amato, A.; Calvani, M.; Cucinotta, D.; et al. Very high frequency of the polymorphism for the insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) at codon 972 (Glycine972Arginine) in Southern Italian women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Horm. Metab. Res. 2010, 42, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshavarzi, F.; Golsheh, S. IRS1- rs10498210 G/A and CCR5-59029 A/G polymorphisms in patients with type 2 diabetes in Kurdistan. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2019, 7, e631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendtorff, N.D.; Lodahl, M.; Boulahbel, H.; Johansen, I.R.; Pandya, A.; Welch, K.O.; Norris, V.W.; Arnos, K.S.; Bitner-Glindzicz, M.; Emery, S.B.; et al. Identification of p.A684V missense mutation in the WFS1 gene as a frequent cause of autosomal dominant optic atrophy and hearing impairment. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 1298–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beller, M.; Bulankina, A.V.; Hsiao, H.-H.; Urlaub, H.; Jäckle, H.; Kühnlein, R.P. PERILIPIN-dependent control of lipid droplet structure and fat storage in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Bosque-Plata, L.; Martínez-Martínez, E.; Espinoza-Camacho, M.Á.; Gragnoli, C. The Role of TCF7L2 in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2021, 70, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, S.V.; Mishra, B.K.; Mannar, V.; Aslam, M.; Banerjee, B.; Agrawal, V. TCF7L2 gene associated postprandial triglyceride dysmetabolism- a novel mechanism for diabetes risk among Asian Indians. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 973718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarte, J.; Wang, J.; McIntyre, A.D.; Hegele, R.A. Prevalence of severe hypertriglyceridemia and pancreatitis in familial partial lipodystrophy type 2. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2021, 15, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.-X.; Zhang, L.; Ye, W.; Wen, Y.-B.; Si, N.; Li, H.; Li, M.-X.; Li, X.-M.; Zheng, K. The renal manifestations of type 4 familial partial lipodystrophy: A case report and review of litera-ture. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Cui, J.; Goodarzi, M.O. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk of type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke. Diabetes 2021, 70, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jéru, I.; Vantyghem, M.-C.; Bismuth, E.; Cervera, P.; Barraud, S.; Auclair, M.; Vatier, C.; Lascols, O.; Savage, D.B.; Vigouroux, C. Diagnostic Challenge in PLIN1-Associated Familial Partial Lipodystrophy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 6025–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, T.W.; A Patel, K.; Colclough, K.; Curran, J.; Dale, J.; Davis, N.; Savage, D.B.; E Flanagan, S.; Ellard, S.; Hattersley, A.T.; et al. PLIN1 Haploinsufficiency Is Not Associated with Lipodystrophy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3225–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, C.C.; A Zaghloul, N.; E Davis, E.; Stoetzel, C.; Diaz-Font, A.; Rix, S.; Alfadhel, M.; Lewis, R.A.; Eyaid, W.; Banin, E.; et al. Hypomorphic mutations in syndromic encephalocele genes are associated with Bardet-Biedl syn-drome. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genetics Home Reference. DMPK Gene; NIH: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2017; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/DMPK# (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Jia, Y.-X.; Dong, C.-L.; Xue, J.-W.; Duan, X.-Q.; Xu, M.-Y.; Su, X.-M.; Li, P. Myotonic dystrophy type 1 presenting with dyspnea: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 7060–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pozos, K.; Ortíz-López, M.G.; Peña-Espinoza, B.I.; Granados-Silvestre, M.d.L.Á.; Jiménez-Jacinto, V.; Verleyen, J.; Tekola-Ayele, F.; Sanchez-Flores, A.; Menjivar, M. Whole-exome sequencing in maya indigenous families: Variant in PPP1R3A is associated with type 2 diabetes. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2018, 293, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapito, R.; Paul, N.; Untrau, M.; Le Gentil, M.; Ott, L.; Alsaleh, G.; Jochem, P.; Radosavljevic, M.; Le Caignec, C.; David, A.; et al. A de novo ADCY5 mutation causes early-onset autosomal dominant chorea and dystonia. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera-Venegas, I.-G.; Mora-Peña, J.-D.; Velazquez-Villafaña, M.; Gonzalez-Dominguez, M.-I.; Barbosa-Sabanero, G.; Gomez-Zapata, H.-M.; Lazo-De-La-Vega-Monroy, M.-L. Association of diabetes-related variants in ADCY5 and CDKAL1 with neonatal insulin, C-peptide, and birth weight. Endocrine 2021, 74, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.-W.; Liu, M.-N.; Wang, X.; Cheng, S.-Q.; Li, C.-S.; Bai, Y.-Y.; Yang, L.-L.; Wang, X.-X.; Wen, J.; Xu, W.-J.; et al. Exploring the common pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus via microarray data analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1071391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Levi, A.; Barabash, A.; Valerio, J.; de la Torre, N.G.; Mendizabal, L.; Zulueta, M.; de Miguel, M.P.; Diaz, A.; Duran, A.; Familiar, C.; et al. Genetic variants for prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus and modulation of susceptibility by a nutritional intervention based on a Mediterranean diet. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1036088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, S.; Fehlings, C.; Herbach, N.; Hofmann, A.; von Waldthausen, D.C.; Kessler, B.; Ulrichs, K.; Chodnevskaja, I.; Moskalenko, V.; Amselgruber, W.; et al. Glucose Intolerance and Reduced Proliferation of Pancreatic. Diabetes 2010, 59, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Delessa, C.T.; Augustin, R.; Bakhti, M.; Colldén, G.; Drucker, D.J.; Feuchtinger, A.; Caceres, C.G.; Grandl, G.; Harger, A.; et al. The glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) regulates body weight and food intake via CNS-GIPR signaling. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 833–844.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laviola, L.; Giorgino, F.; Chow, J.C.; A Baquero, J.; Hansen, H.; Ooi, J.; Zhu, J.; Riedel, H.; Smith, R.J. The adapter protein Grb10 associates preferentially with the insulin receptor as compared with the IGF-I receptor in mouse fibroblasts. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qiu, W.; Meng, Q.; Liu, M.; Lin, W.; Yang, H.; Wang, R.; Dong, J.; Yuan, N.; Zhou, Z.; et al. GRB10 rs1800504 Polymorphism Is Associated with the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 728976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohani, Z.N.; Anand, S.S.; Robiou-Du-Pont, S.; Morrison, K.M.; McDonald, S.D.; Atkinson, S.A.; Teo, K.K.; Meyre, D. Risk alleles in/near ADCY5, ADRA2A, CDKAL1, CDKN2A/B, GRB10, and TCF7L2 elevate Plasma glucose levels at birth and in early childhood: Results from the FAMILY study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, L.R.; Greeley, S.A.W. Congenital forms of diabetes: The beta-cell and beyond. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2018, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wejaphikul, K.; Srilanchakon, K.; Kamolvisit, W.; Jantasuwan, S.; Santawong, K.; Tongkobpetch, S.; Theerapanon, T.; Damrongmanee, A.; Hongsawong, N.; Ukarapol, N.; et al. Novel Variants and Phenotypes in NEUROG3-Associated Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Yan, J.; Yang, D.; Luo, S.; Zheng, X.; Yang, G.; Li, Z.; Xu, W.; et al. Recognition of maturity-onset diabetes of the young in China. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bergmann, A.; Reimann, M.; Schulze, J.; Bornstein, S.R.; Schwarz, P.E.H. Genetic variation of Neurogenin 3 is slightly associated with hyperproinsulinaemia and progression toward type 2 diabetes. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2008, 116, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, T.; Tobe, K.; Hara, K.; Yasuda, K.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Ikegami, H.; Ito, C.; Kadowaki, T. Variants of neurogenin 3 gene are not associated with Type II diabetes in Japanese subjects. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient ID | Circumstance of Diabetes Discovery | Age at Diagnosis of Diabetes (Years) | Age at Survey | Treatement | Family Members with Diabetes | Comorbidities (Other Clinical Features) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Polyuria, polydipsia FPG = 27.40 mmol/L HbA1c = 9.1% | 19 | 30 s | Insulin (Actrapid 4 U + Insulatard 8 U, 3×/day) than switched to OAD | 1 | Nephropathy, High levels of T-CHL Gastric problems |

| P2 | Polyuria, polydipsia Weight loss FPG = 14.20 mmol/L HbA1c = 14.0% | 6 | 10 s | Insulin (Insulatard 12/4 U; Actrapid 4/2 U) | 0 | No other clinical signs |

| P3 | Polyuria, polydipsia HbA1c = 7.0% | 24 | 30 s | OAD than switched to Insulin (Actrapid 5 U, Insulatard 10 U) | 1 | Hypoglycemic often at night Acute pyelonephritis, pelviperitonitis, Hypertriglyceridemia anxiety |

| P4 | Polyuria, polydipsia FPG = 16.70 mmol/L HbA1c = 10.0% | 18 | 20 s | OAD | 2 | No other clinical signs |

| P5 | Pancreas inflammation | 17 | 20 s | Insulin (Actrapid 14/14/14 U; Insulatard 28/26 U) | 0 | Inflammation of the pancreas (Stage1) Hepatic thrombosis, Hypothyroidism High TG and T-CHL levels |

| P6 | Polyuria, polydipsia FPG = 22.20 mmol/L HbA1c = 13.0% | 15 | 20 s | Insulin than switched to OAD than insulin | 0 | Allergy and astigmatism |

| P7 | Polyuria, polydipsia FPG = 16.70 mmol/L HbA1c = 8.9% | 4 | 20 s | Insulin | 2 | Partial hearing loss, Bilateral optic atrophy Diabetic neuropathy |

| P8 | Polyuria, polydipsia FPG = 21.10 mmol/L HbA1c = 12.0% | 23 | 20 s | OAD | 1 | No other clinical signs |

| P9 | Polyuria, polydipsia FPG = 16.70 mmol/L HbA1c = 9.0% | 15 | 20 s | OAD + insulin | 2 | Obesity Hypertension |

| P10 | Polyuria, polydipsia Nausea FPG = 11.40 mmol/L HbA1c = 10.8% | 25 | 20 s | OAD | 3 | Decreased visual acuity and migraine PCOS, irregular menstrual cycle with intense pain |

| P11 | Polyuria, polydipsia FPG = 13.90 mmol/L | 18 | 20 s | Insulin | 2 | Delayed staturo-ponderal development, Finger infection, Glaucoma Intellectual disability |

| Patient ID | FPG (mmol/L) | HbA1C (%) | T-CHL (mmol/L) | TG (mmol/L) | HDL (mmol/L) | LDL (mmol/L) | Creatinine (µmol/L) | CRP (mg/L) | C-Peptide Basal (ng/mL) | Pancreatic Antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 3.40 | 9.01 | 3.35 | 0.89 | 1.32 | 1.55 | 64.00 | 0.97 | 2.20 | Two negative |

| P2 | 7.80 | 7.8 | 4.41 | 0.50 | 1.96 | 2.32 | 29.00 | 0.19 | 0.02 | Two negative |

| P3 | 13.00 | 13.8 | 7.15 | 1.80 | 1.29 | 5.16 | 49.00 | 2.32 | 0.01 | Two negative |

| P4 | 9.82 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 2.35 | 1.39 | 2.64 | 57.40 | 4.26 | 0.01 | Two negative |

| P5 | 21.06 | 16.3 | 5.29 | 6.77 | NA | 1.58 | 59.00 | NA | NA | Two negative |

| P6 | 17.80 | 10.0 | 3.79 | 0.59 | 1.39 | 2.06 | 50.00 | 1.78 | 1.70 | Two negative |

| P7 | 11.60 | 7.3 | 3.24 | 0.83 | 1.14 | 1.72 | 71.50 | 4.51 | 0.01 | Three negative |

| P8 | 10.70 | 9.1 | 3.39 | 1.33 | 1.29 | 1.50 | 31.20 | 12.10 | 1.51 | Two negative |

| P9 | 5.82 | 10.4 | 3.00 | 1.65 | 0.72 | 1.52 | 37.30 | 3.10 | 1.70 | Two negative |

| P10 | 13.70 | 9.2 | 6.13 | 2.50 | 1.02 | 3.97 | 45.70 | NA | 1.29 | Two negative |

| P11 | 13.70 | 6.5 | 4.16 | 0.61 | 1.24 | 2.64 | 38.40 | <0.6 | 0.02 | Two negative |

| Patient ID | Variants Combination | VarCoPP Score | Prediction of Pathogenicity | Type of Digenic Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3 | LMNA: 4:151791682:T:C LRBA: 1:156108510:C:T | 0.81 | Disease-causing with 99% confidence | True digenic |

| P5 | No variant combination | - | - | - |

| P8 | ADCY5: 3:123167364:G:A PPP1R3A: 7:113518880:G:A | 0.82 | Disease-causing with 99% confidence | True digenic |

| P9 | PPP1R3A: 7:113518880:G:A GIPR: 19:46176123:G:T | 0.67 | Low pathogenicity | True digenic |

| P10 | No variant combination | - | - | - |

| P11 | GRB10: 7:50737469:G:C NEUROG3: 10:71332289:A:T | 0.80 | Disease-causing with 99% confidence | Monogenic + modifier |

| Patient ID | Typical Clinical Features | Causative Genes | Diabetes Subtype |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Nephropathy High levels of CHL Gastric problems | HNF1A | MODY_3 (HNF1A_MODY) |

| P2 | Absence of other clinical signs | WFS1 | Isolated diabetes with low penetrance for Wolfram syndrome features |

| P3 | Hypoglycemic often at night Acute pyelonephritis, pelviperitonitis State of anxiety | LMNA LRBA | Partial familial lipodystrophy type 2 |

| P4 | Absence of other clinical signs | IRS1 | Early onset T2D |

| P5 | Inflammation of the pancreas Liver thrombosis Hypothyroidism High TG and CHL levels | MKS1 DMPK | Unspecified atypical MFD with Meckel Syndrome comorbidity |

| P6 | Astigmatism and allergies | WFS1 | Isolated diabetes with low penetrance for Wolfram syndrome features |

| P7 | Partial hearing loss Bilateral optic atrophy Diabetic neuropathy | WFS1 | Wolfram syndrome |

| P8 | Absence of other clinical signs | PPP1R3A ADCY5 | Unspecified atypical MFD |

| P9 | Obesity Hypertension | PPP1R3A GIPR | Unspecified atypical MFD |

| P10 | Diminished visual acuity and migraine PCOS Irregular menstrual cycle with intense pain | TCF7L2 PLIN 1 | Partial familial lipodystrophy type 4 |

| P11 | Delayed staturo-ponderal development Finger infection Glaucoma Intellectual disability | GRB 10 NEUROG3 | Unspecified atypical MFD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kheriji, N.; Dallali, H.; Gharbi, M.; Krir, A.; Bahlous, A.; Ben Ahmed, M.; Mahjoub, F.; Abid, A.; Jamoussi, H.; Kefi, R. Genomic Insights into Unspecified Monogenic Forms of Diabetes and Their Associated Comorbidities: Implication for Treatment. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121055

Kheriji N, Dallali H, Gharbi M, Krir A, Bahlous A, Ben Ahmed M, Mahjoub F, Abid A, Jamoussi H, Kefi R. Genomic Insights into Unspecified Monogenic Forms of Diabetes and Their Associated Comorbidities: Implication for Treatment. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121055

Chicago/Turabian StyleKheriji, Nadia, Hamza Dallali, Mariem Gharbi, Asma Krir, Afef Bahlous, Melika Ben Ahmed, Faten Mahjoub, Abdelmajid Abid, Henda Jamoussi, and Rym Kefi. 2025. "Genomic Insights into Unspecified Monogenic Forms of Diabetes and Their Associated Comorbidities: Implication for Treatment" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121055

APA StyleKheriji, N., Dallali, H., Gharbi, M., Krir, A., Bahlous, A., Ben Ahmed, M., Mahjoub, F., Abid, A., Jamoussi, H., & Kefi, R. (2025). Genomic Insights into Unspecified Monogenic Forms of Diabetes and Their Associated Comorbidities: Implication for Treatment. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121055