Alleviation of Aflatoxin B1-Induced Hepatic Damage by Propolis: Effects on Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Expression

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1.

- How does propolis supplementation influence oxidative stress and inflammation in AFB1-induced liver damage?

- RQ2.

- Can propolis mitigate AFB1-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes and promote liver regeneration?

- RQ3.

- What are the potential immunomodulatory effects of propolis in counteracting AFB1-induced immunosuppression?

- RQ4.

- How effective is propolis as a natural dietary intervention in reducing the toxicological impact of AFB1 exposure?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

2.2. Preparation and Dosage of AFB1

2.3. Extraction and Dosage of Propolis

2.4. Experimental Groups

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Measurements

2.6. Histological Staining

2.7. Immunohistochemistry

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, Nrf2, and HO-1 Levels

3.2. Histological Investigation

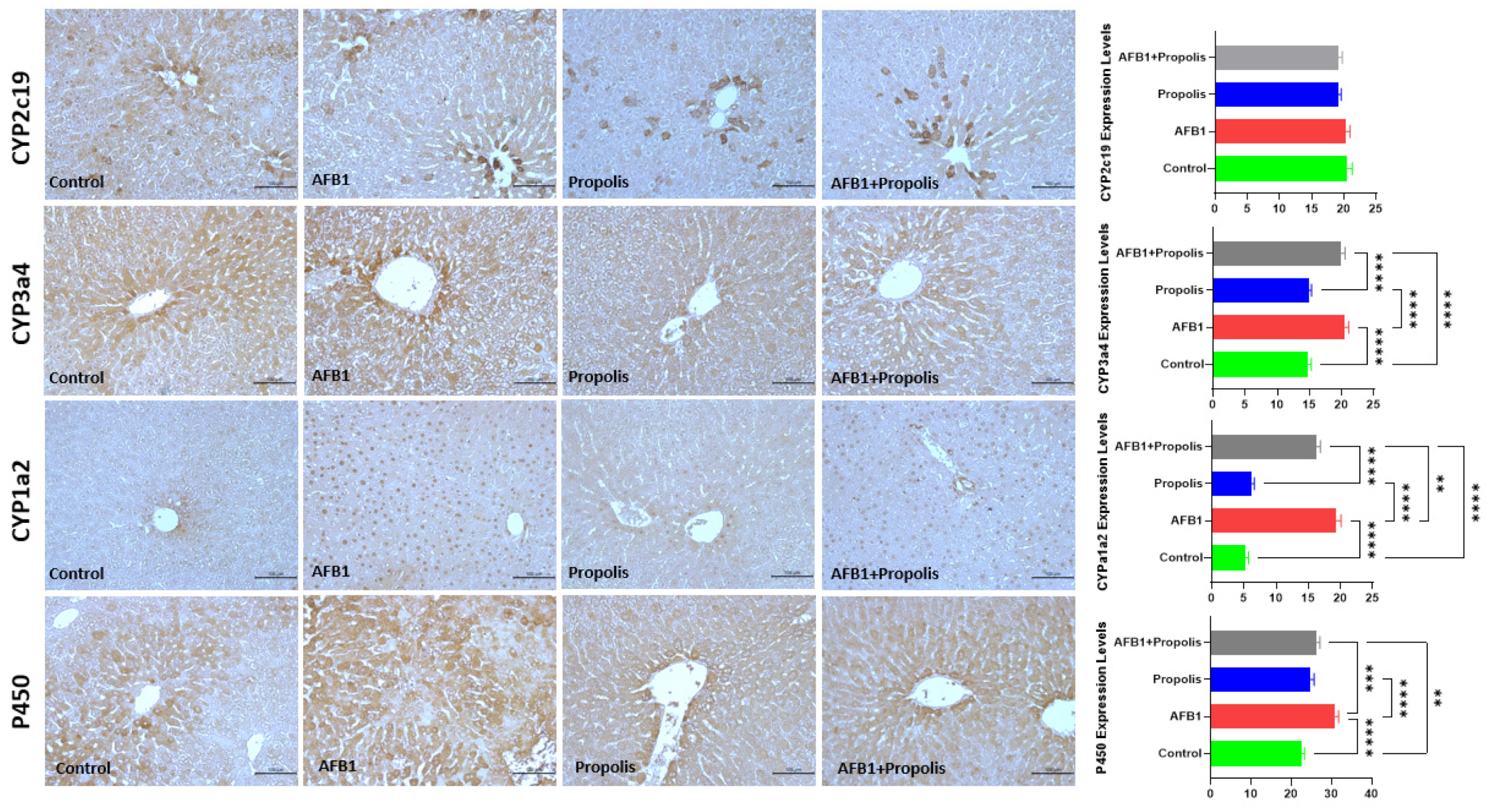

3.3. Immunohistochemical Investigation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gong, Y.Y.; Watson, S.; Routledge, M.N. Aflatoxin Exposure and Associated Human Health Effects, a Review of Epidemiological Studies. Food Saf. 2016, 4, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlangwiset, P.; Shephard, G.S.; Wu, F. Aflatoxins and growth impairment: A review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2011, 41, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.N.; Yu, W.; Teoh, W.W.; Ardin, M.; Jusakul, A.; Ng, A.W.T.; Boot, A.; Abedi-Ardekani, B.; Villar, S.; Myint, S.S.; et al. Genome-scale mutational signatures of aflatoxin in cells, mice, and human tumors. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Singh, V.K.; Dwivedy, A.K.; Chaudhari, A.K.; Upadhyay, N.; Singh, P.; Sharma, S.; Dubey, N.K. Encapsulation in chitosan-based nanomatrix as an efficient green technology to boost the antimicrobial, antioxidant and in situ efficacy of Coriandrum sativum essential oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, F.; Tao, W.; Ye, R.; Li, Z.; Lu, Q.; Shang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Fang, J.; Bhutto, Z.A.; Liu, J. Penthorum Chinense Pursh Extract Alleviates Aflatoxin B1-Induced Liver Injury and Oxidative Stress Through Mitochondrial Pathways in Broilers. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 822259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, C.P.; Turner, P.C. The toxicology of aflatoxins as a basis for public health decisions. Mutagenesis 2002, 17, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ogunade, I.M.; Vyas, D.; Adesogan, A.T. Aflatoxin in Dairy Cows: Toxicity, Occurrence in Feedstuffs and Milk and Dietary Mitigation Strategies. Toxins 2021, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Wang, F.; Tang, L.; Massey, M.E.; Mitchell, N.J.; Su, J.; Williams, J.H.; Phillips, T.D.; Wang, J.S. Integrative toxicopathological evaluation of aflatoxin B1 exposure in F344 rats. Toxicol. Pathol. 2013, 41, 1093–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authority, E.F.S. Outcome of a public consultation on the draft risk assessment of aflatoxins in food. EFSA Support. Publ. 2020, 17, 1798E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altabbal, S.; Athamnah, K.; Rahma, A.; Wali, A.F.; Eid, A.H.; Iratni, R.; Al Dhaheri, Y. Propolis: A Detailed Insight of Its Anticancer Molecular Mechanisms. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, E.A.; Chen, C.Y.; Wu, H.N.; Chien, C.C.; Chen, S.C. Propolis alleviates 4-aminobiphenyl-induced oxidative DNA damage by inhibition of CYP2E1 expression in human liver cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Liou, C.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.C. Induction of oxidative DNA damage by flavonoids of propolis: Its mechanism and implication about antioxidant capacity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavacca, A.; Sangiovanni, E.; Racagni, G.; Dell’Agli, M. The antiviral and immunomodulatory activities of propolis: An update and future perspectives for respiratory diseases. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 897–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounieb, F.; Ramadan, L.; Akool, E.S.; Balah, A. Propolis alleviates concanavalin A-induced hepatitis by modulating cytokine secretion and inhibition of reactive oxygen species. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2017, 390, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzularab, B.M.; Megeed, M.; Yehia, M. Propolis nanoparticles modulate the inflammatory and apoptotic pathways in carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis and nephropathy in rats. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tang, L.; Wang, J.S. Assessment of the adverse impacts of aflatoxin B1 on gut-microbiota dependent metabolism in F344 rats. Chemosphere 2019, 217, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, L.; Glenn, T.C.; Wang, J.S. Aflatoxin B1 Induced Compositional Changes in Gut Microbial Communities of Male F344 Rats. Toxicol. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 2016, 150, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, W.P.; Sabran, M.R.; Than, L.T.; Abd-Ghani, F. Metagenomic and proteomic approaches in elucidating aflatoxin B1 detoxification mechanisms of probiotic Lactobacillus casei Shirota towards intestine. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2022, 160, 112808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Xu, J.; Li, G.; Liu, T.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Luo, L. Ethanol extract of propolis prevents high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and obesity in association with modulation of gut microbiota in mice. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, H.S.; Al-Yousef, H.M.; Ashour, A.E.; Ahmed, A.F.; Amina, M.; Issa, I.S.; Bhat, R.S. Antioxidant and hepatorenal protective effects of bee pollen fractions against propionic acid-induced autistic feature in rats. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5114–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğanyiğit, Z.; Yakan, B.; Okan, A.; Silici, S. Antioxidative role of propolis on LPS induced renal damage. EuroBiotech J. 2020, 4, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braakhuis, A. Evidence on the Health Benefits of Supplemental Propolis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mekkawy, H.I.; Al-Kahtani, M.A.; Shati, A.A.; Alshehri, M.A.; Al-Doaiss, A.A.; Elmansi, A.A.; Ahmed, A.E. Black tea and curcumin synergistically mitigate the hepatotoxicity and nephropathic changes induced by chronic exposure to aflatoxin-B1 in Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Q.; Ji, C.; Zhao, L. Transcriptional Profiling of Aflatoxin B1-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response in Macrophages. Toxins 2021, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, D.; Keskin, E. The effect of curcumin on some cytokines, antioxidants and liver function tests in rats induced by Aflatoxin B1. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.N.; Zeng, Z.Z.; Wu, P.; Jiang, W.D.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Kuang, S.Y.; Tang, L.; Feng, L.; Zhou, X.Q. Dietary Aflatoxin B1 attenuates immune function of immune organs in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) by modulating NF-κB and the TOR signaling pathway. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1027064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-Y.; Zhan, D.-L.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Wang, W.-H.; He, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, Z.-N. Aflatoxin B1 enhances pyroptosis of hepatocytes and activation of Kupffer cells to promote liver inflammatory injury via dephosphorylation of cyclooxygenase-2: An in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo study. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 3305–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zuo, S.; Wang, H.; Bian, X.; Chen, G.; Huang, S.; Dai, H.; Liu, F.; Dong, H. Aflatoxin B1 Exposure in Sheep: Insights into Hepatotoxicity Based on Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Injury, Apoptosis, and Gut Microbiota Analysis. Toxins 2022, 14, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Tian, E.; Hao, Z.; Tang, S.; Wang, Z.; Sharma, G.; Jiang, H.; Shen, J. Aflatoxin B1 Toxicity and Protective Effects of Curcumin: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarotimi, O.J.; Gbore, F.A.; Adu, O.A.; Oloruntola, O.D.; Jimoh, O.A. Ameliorative effects of Sida acuta and vitamin C on serum DNA damage, pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in roosters fed aflatoxin B1 contaminated diets. Toxicon 2023, 236, 107330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Yuan, W.; Wu, H.; Yin, X.; Xuan, H. Bioactive components and mechanisms of Chinese poplar propolis alleviates oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced endothelial cells injury. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Seedi, H.R.; Eid, N.; Abd El-Wahed, A.A.; Rateb, M.E.; Afifi, H.S.; Algethami, A.F.; Zhao, C.; Al Naggar, Y.; Alsharif, S.M.; Tahir, H.E.; et al. Honey Bee Products: Preclinical and Clinical Studies of Their Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Properties. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 761267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashiwakura, J.-i.; Yoshihara, M.; Saitoh, K.; Kagohashi, K.; Sasaki, Y.; Kobayashi, F.; Inagaki, I.; Kitai, Y.; Muromoto, R.; Matsuda, T. Propolis suppresses cytokine production in activated basophils and basophil-mediated skin and intestinal allergic inflammation in mice. Allergol. Int. 2021, 70, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Xuan, H. The protective effects of propolis against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute liver injury by modulating serum metabolites and gut flora. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlavani, N.; Malekahmadi, M.; Firouzi, S.; Rostami, D.; Sedaghat, A.; Moghaddam, A.B.; Ferns, G.A.; Navashenaq, J.G.; Reazvani, R.; Safarian, M.; et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the effects of Propolis in inflammation, oxidative stress and glycemic control in chronic diseases. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.; Burgos, V.; Marín, V.; Camins, A.; Olloquequi, J.; González-Chavarría, I.; Ulrich, H.; Wyneken, U.; Luarte, A.; Ortiz, L.; et al. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester (CAPE): Biosynthesis, Derivatives and Formulations with Neuroprotective Activities. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanov, Y. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE): Pharmacodynamics and potential for therapeutic application. Pharmacia 2019, 66, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuran, J.; Cepanec, I.; Mašek, T.; Radić, B.; Radić, S.; Tlak Gajger, I.; Vlainić, J. Propolis Extract and Its Bioactive Compounds—From Traditional to Modern Extraction Technologies. Molecules 2021, 26, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranneh, Y.; Akim, A.M.; Hamid, H.A.; Khazaai, H.; Fadel, A.; Mahmoud, A.M. Stingless bee honey protects against lipopolysaccharide induced-chronic subclinical systemic inflammation and oxidative stress by modulating Nrf2, NF-κB and p38 MAPK. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Xie, W.; Huang, D.; Cui, Y.; Yue, J.; He, Q.; Jiang, L.; Xiong, J.; Sun, W.; Yi, Q. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester attenuates osteoarthritis progression by activating NRF2/HO-1 and inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 50, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Chaudhari, A.Z.; Teli, D.; Balar, P.; Vora, L. Propolis and Their Active Constituents for Chronic Diseases. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulhendri, F.; Lesmana, R.; Tandean, S.; Christoper, A.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Irsyam, I.; Suwantika, A.A.; Abdulah, R.; Wathoni, N. Recent Update on the Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Propolis. Molecules 2022, 27, 8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.A.Z.; Abdel-Maksoud, F.M.; Abd Elaziz, H.O.; Al-Brakati, A.; Elmahallawy, E.K. Descriptive Histopathological and Ultrastructural Study of Hepatocellular Alterations Induced by Aflatoxin B1 in Rats. Animals 2021, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, T.; Yener, Z.; Celik, I. Histopathological and biochemical investigations of protective role of honey in rats with experimental aflatoxicosis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloi, T.P.; Ziqubu, K.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Mabaso, N.H.; Ndlovu, Z. Aflatoxin B1-induced hepatotoxicity through mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation as central pathological mechanisms: A review of experimental evidence. Toxicology 2024, 509, 153983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kabalı, S.; Öner, N.; Kara, A.; Söğüt, M.Ü.; Elgün, Z. Alleviation of Aflatoxin B1-Induced Hepatic Damage by Propolis: Effects on Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Expression. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010056

Kabalı S, Öner N, Kara A, Söğüt MÜ, Elgün Z. Alleviation of Aflatoxin B1-Induced Hepatic Damage by Propolis: Effects on Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Expression. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleKabalı, Sevtap, Neslihan Öner, Ayca Kara, Mehtap Ünlü Söğüt, and Zehra Elgün. 2026. "Alleviation of Aflatoxin B1-Induced Hepatic Damage by Propolis: Effects on Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Expression" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010056

APA StyleKabalı, S., Öner, N., Kara, A., Söğüt, M. Ü., & Elgün, Z. (2026). Alleviation of Aflatoxin B1-Induced Hepatic Damage by Propolis: Effects on Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Expression. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010056