Apple Seed Extract in Cancer Treatment: Assessing Its Effects on Liver Damage and Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extraction and Concentration of Apple Seed Ethanol Extract

2.2. Primary Hepatocyte Isolation and Culture

2.3. Cell Survival Assay

2.4. Cancer Mouse Model

2.5. Paraffin Embedding and Sectioning (Histological Slide Preparation)

2.6. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

2.7. Alizarin Red S Staining

2.8. Immunohistochemistry

2.9. Western Blot

2.10. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

2.11. Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay

2.12. Analysis via ImageJ

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cytoskeletal Changes and Toxicity Assessment Following Treatment with Natural Substances

3.2. Morphological Changes in Hepatocyte Components and Apoptosis Regulation

3.3. Histopathological Changes Following ASE Treatment

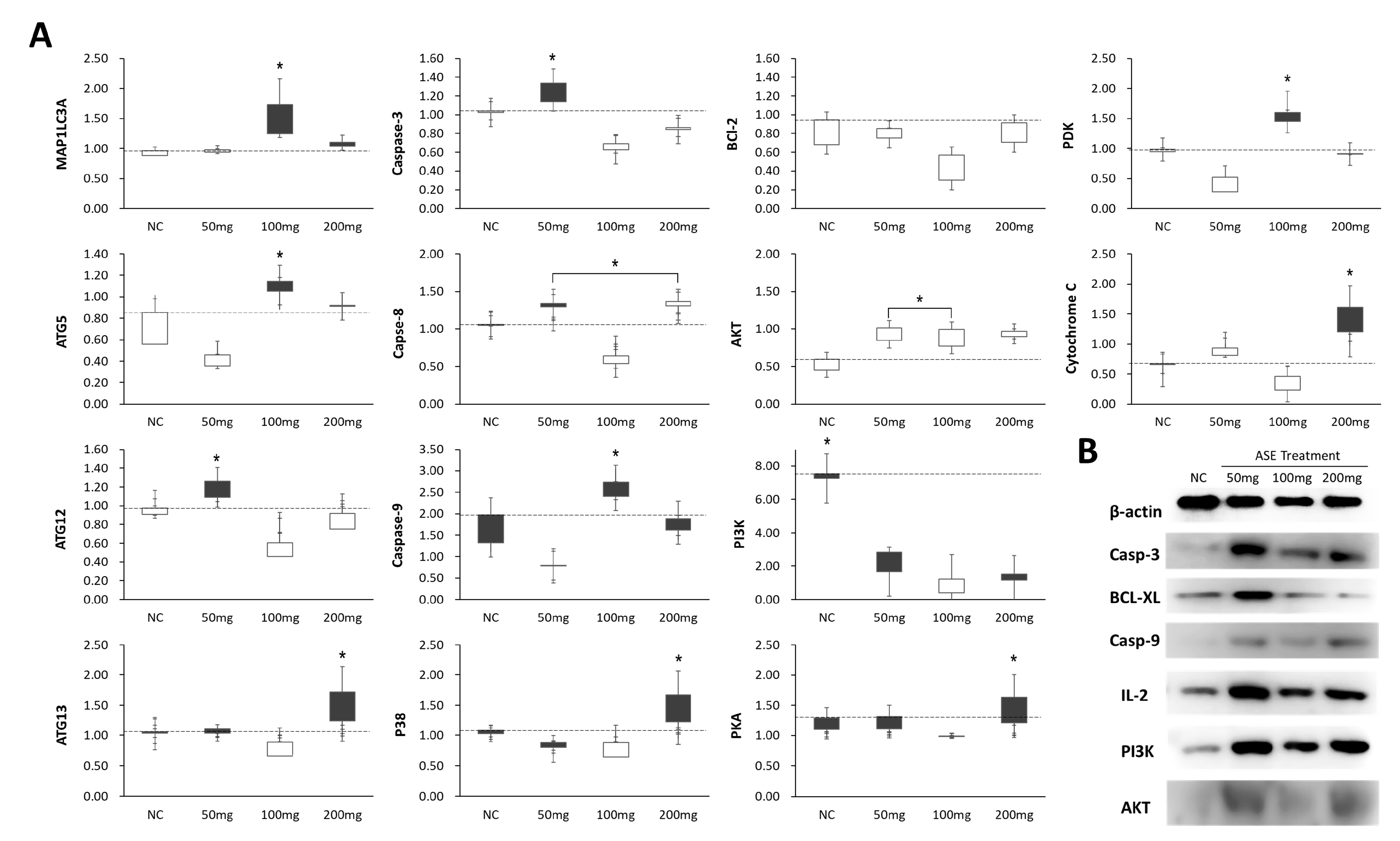

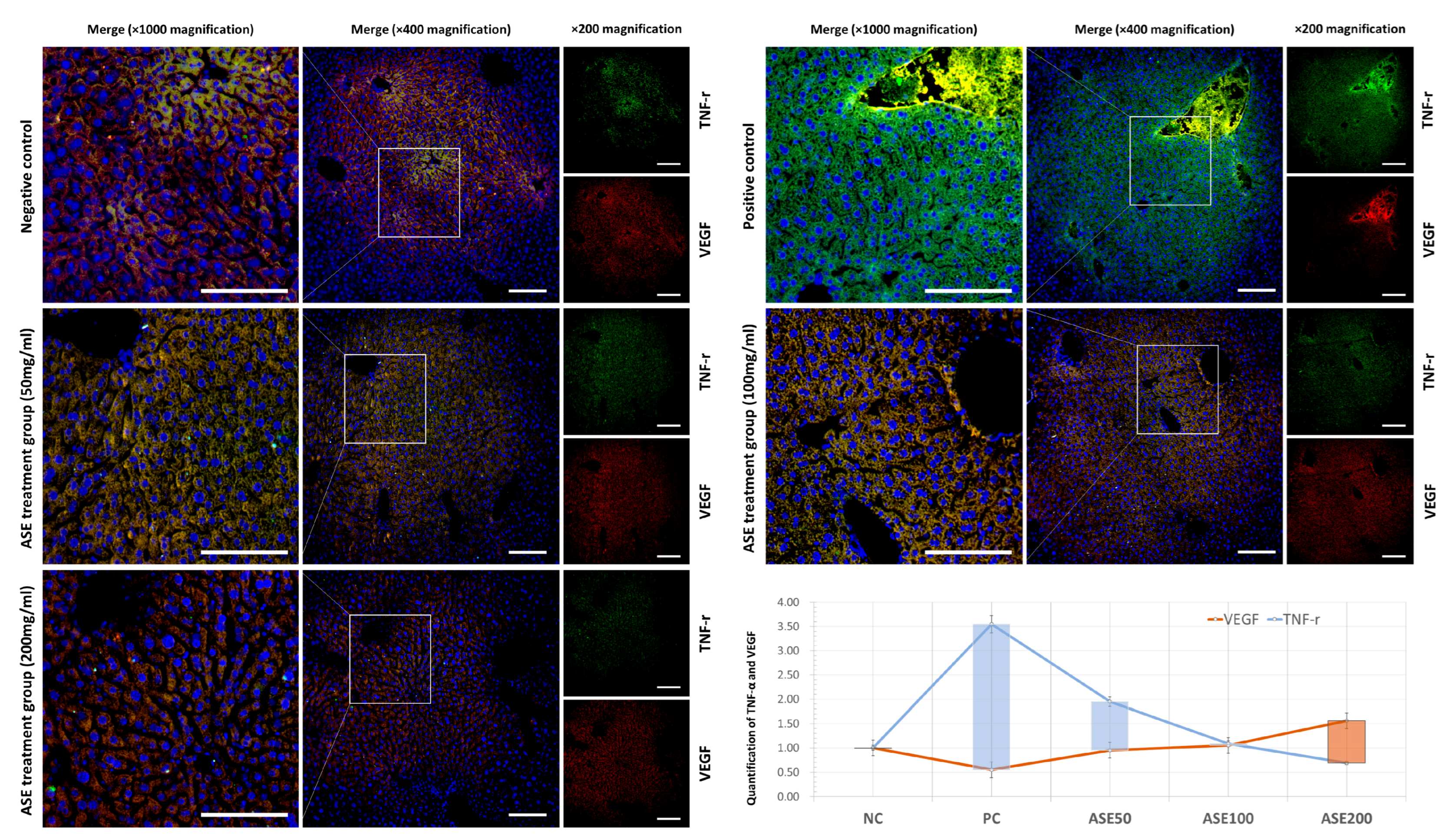

3.4. Effect of ASE Treatment on Programmed Cell Death Expression in Mouse Liver Tissue

3.5. Differences in Programmed Cell Death and Survival Signaling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- King, P.D.; Perry, M.C. Hepatotoxicity of chemotherapy. Oncologist 2001, 6, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbaset, M.A.; Afifi, S.M.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Abdelrahman, S.S.; Saleh, D.O. Neuroprotective effects of trimetazidine against cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy: Involvement of AMPK-mediated PI3K/mTOR, Nrf2, and NF-κB signaling axes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; He, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J.; Wang, J. Amygdalin protects against acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury by suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 624, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Aggarwal, D.; Sehrawat, N.; Yadav, M.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, A.; Zghair, A.N.; Dhama, K.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; et al. Hepatoprotective effects of natural drugs: Current trends, scope, relevance and future perspectives. Phytomedicine 2023, 121, 155100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Zhu, C.; Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Hepatoprotective effects of apple polyphenol extract on aluminum-induced liver oxidative stress in the rat. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 92, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pour, P.H.; Hasanpour, M.; Kesharwani, P.; Sobhani, Z.; Sahebkar, A. Exploring the hepatoprotective effects of apples: A comprehensive review of bioactive compounds and molecular mechanisms. Fitoterapia 2025, 185, 106689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PDQ Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board. Laetrile/Amygdalin (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/hp/laetrile-pdq (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Tang, F.; He, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Zhou, C.; Li, C.; Cheng, M.; Li, D. Amygdalin attenuates acute liver injury induced by LPS/D-galactosamine in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 71, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. The role of TNFα/p53 pathway in endometrial cancer mouse model administered with apple seed extract. Histol. Histopathol. 2022, 37, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, A.B.; Dobson, E.T.A.; Rueden, C.T.; Tomancak, P.; Jug, F.; Eliceiri, K.W. The ImageJ ecosystem: Open-source software for image visualization, processing, and analysis. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibuya, A.; Unuma, T.; Sugimoto, T.; Yamakado, M.; Tagawa, H.; Tagawa, K.; Tanaka, S.; Takanashi, R. Diffuse hepatic calcification as a sequela to shock liver. Gastroenterology 1985, 89, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paley, M.R.; Ros, P.R. Hepatic calcification. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 1998, 36, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, F.; Miao, D.; Emadali, A.; Tzimas, G.N.; Goltzman, D.; Vali, H.; Chevet, E.; Auguste, P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of abnormal calcification following ischemia–reperfusion injury in human liver transplantation. Mod. Pathol. 2007, 20, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaki, M.; Naiki, T.; Brenner, D.A.; Osawa, Y.; Imose, M.; Hayashi, H.; Banno, Y.; Nakashima, S.; Moriwaki, H. Tumor necrosis factor alpha prevents tumor necrosis factor receptor-mediated mouse hepatocyte apoptosis, but not Fas-mediated apoptosis: Role of nuclear factor-κB. Hepatology 2000, 32, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boise, L.H.; Thompson, C.B. Bcl-xL can inhibit apoptosis in cells that have undergone Fas-induced protease activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 3759–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Chandel, N.S.; Williamson, E.K.; Schumacker, P.T.; Thompson, C.B. Bcl-xL regulates the membrane potential and volume homeostasis of mitochondria. Cell 1997, 91, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takehara, T.; Tatsumi, T.; Suzuki, T.; Rucker, E.B., III; Hennighausen, L.; Jinushi, M.; Miyagi, T.; Kanazawa, Y.; Hayashi, N. Hepatocyte-specific disruption of Bcl-xL leads to continuous hepatocyte apoptosis and liver fibrotic responses. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Abdalla, F.C.; Abeliovich, H.; Abraham, R.T.; Acevedo-Arozena, A.; Adeli, K.; Agholme, L.; Agnello, M.; Agostinis, P.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 2012, 8, 445–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsy, M.A.; Abdel-Latif, R.; Abdel Hafez, S.M.N.; Kandeel, M.; Abdel-Gaber, S.A. Paeonol protects against methotrexate hepatotoxicity by repressing oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis—The role of drug efflux transporter. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Gene | Primer (5′ → 3′) | Gene Bank | Product Size (bp) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GAPDH | F: CCCGTTCGACAGACAGCCGTG | NM_001206359.1 | 238 | 60 |

| R: CCGCCTTGACTGTGCCGTGG | |||||

| 2 | Cytochrome C | F: GAGGCAAGCATAAGACTGGA | NM_007808.5 | 133 | 60 |

| R: TACTCCATCAGGGTATCCTC | |||||

| 3 | BAD | F: GCCCTAGGCTTGAGGAAGTC | NM_007522.3 | 109 | 61 |

| R: CAAACTCTGGGATCTGGAACA | |||||

| 4 | p53 | F: ACAGTCGGATATCAGCCTCG | NM_011640.4 | 275 | 58 |

| R: TTTTTTGAGAAGGGACAAAAGATG | |||||

| 5 | Caspase-9 | F: AGTTCCCGGGTGCTGTCTAT | NM_001429869.1 | 152 | 60 |

| R: GCCATGGTCTTTCTGCTCAC | |||||

| 6 | Caspase-3 | F: CCTCAGAGAGACATTCATGG | NM_009810.3 | 226 | 60 |

| R: GCAGTAGTCGCCTCTGAAGA | |||||

| 7 | Caspase-8 | F: GCAGAAAGTCTGCCTCATCC | NM_001420041.1 | 212 | 60 |

| R: GGCCTCCATCTATGACCTGA | |||||

| 8 | BAX | F: GTGAGCGGCTGCTTGTCT | NM_007527.4 | 68 | 61 |

| R: GGTCCCGAAGTAGGAGAGGA | |||||

| 9 | p38 | F: TGCCATTCATGGGCACTGAT | NM_001361642.1 | 402 | 58 |

| R: GATTCACAGCCTGAGGGCTT | |||||

| 10 | BCl-xl | F: AACATCCCAGCTTCACATAACCCC | NM_001289717.2 | 94 | 62 |

| R: GCGACCCCAGTTTACTCCATCC | |||||

| 11 | BCl-2 | F: CAGGTATGCACCCAGAGTGA | NM_009741.5 | 64 | 60 |

| R: GTCTCTGAAGACGCTGCTCA | |||||

| 12 | NF-kB | F: ACCACTGCTCAGGTCCACTGTC | NM_008689.3 | 81 | 63 |

| R: GCTGTCACTATCCCGGAGTTCA | |||||

| 13 | PKC | F: TGGGGTCCTGCTGTATGAGA | NM_011102.5 | 309 | 58 |

| R: TCAAAGTTTTCGCCACTGCG | |||||

| 14 | VEGF | F: TTACTGCTGTACCTCCACC | NM_009505.4 | 189 | 58 |

| R: ACAGGACGGCTTGAAGATG | |||||

| 15 | IGFBP3 | F: AAGCACCTACCTCCCCTCCCAA | NM_008343.2 | 98 | 64 |

| R: TGCTGGGGACAACCTGGCTTTC | |||||

| 16 | IGF-1 | F: TGTCGTCTTCACATCTCTTCTACCTG | NM_001111276.1 | 121 | 62 |

| R: CCACACACGAACTGAAGAGCGT | |||||

| 17 | AKT | F: TGAAAACCTTCTGTGGGACC | NM_007434.4 | 145 | 60 |

| R: TGGTCCTGGTTGTAGAAGGG | |||||

| 18 | PKA | F: CAGGAAAGCGCTCCAGATAC | NM_008854.5 | 229 | 60 |

| R: AAGGGAAGGTTGGCGTTACT | |||||

| 19 | PI3K | F: AGGAGCGGTACAGCAAAGAA | NM_001077495.2 | 270 | 60 |

| R: GCCGAACACCTTTTTGAGTC | |||||

| 20 | PDK | F: CCGGGCCAGGTGGACTTC | NM_172665.5 | 123 | 60 |

| R: GCAATCTTGTCGCAGAAACATAAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oh, M.-J.; Park, Y.-S.; Mo, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-H. Apple Seed Extract in Cancer Treatment: Assessing Its Effects on Liver Damage and Recovery. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010055

Oh M-J, Park Y-S, Mo J-Y, Kim S-H. Apple Seed Extract in Cancer Treatment: Assessing Its Effects on Liver Damage and Recovery. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Min-Jee, Yong-Su Park, Ji-Yeon Mo, and Sang-Hwan Kim. 2026. "Apple Seed Extract in Cancer Treatment: Assessing Its Effects on Liver Damage and Recovery" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010055

APA StyleOh, M.-J., Park, Y.-S., Mo, J.-Y., & Kim, S.-H. (2026). Apple Seed Extract in Cancer Treatment: Assessing Its Effects on Liver Damage and Recovery. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010055