Autophagy Dysregulation in Crohn’s Disease and Colorectal Cancer—An Analysis of BECN1, PINK1, and LAMP2 Gene Expression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Methods

2.1.1. Study Design

2.1.2. Bioethical Consent

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

2.2.2. Microarray Analysis

2.3. Limitations of the Study

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Experimental Statistical Analysis

2.4.2. Supportive Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BECN1 | the human gene encoding the Beclin-1 protein |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| CMA | chaperone-mediated autophagy |

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

| CSI, CSII, CSIII and CSIV | different stages of colon cancer |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel disease |

| LAMP2 | Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 |

| mTOR | major cell proliferation pathways |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced kinase 1 |

| UC | ulcerative colitis |

References

- Verdier, J.; Breunig, I.R.; Ohse, M.C.; Roubrocks, S.; Kleinfeld, S.; Roy, S.; Streetz, K.; Trautwein, C.; Roderburg, C.; Sellge, G. Faecal Micro-RNAs in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2020, 14, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkholm, P. Review article: The incidence and prevalence of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawki, S.; Ashburn, J.; Signs, S.A.; Huang, E. Colon Cancer: Inflammation-Associated Cancer. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 27, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanders, L.K.; Dekker, E.; Pullens, B.; Bassett, P.; Travis, S.P.; East, J.E. Cancer risk after resection of polypoid dysplasia in patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis: A meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M.D.; Saunders, B.P.; Wilkinson, K.H.; Rumbles, S.; Schofield, G.; Kamm, M.A.; Williams, C.B.; Price, A.B.; Talbot, I.C.; Forbes, A. Thirty-year analysis of a colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugerie, L.; Itzkowitz, S.H. Cancers complicating inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follin-Arbelet, B.; Cvancarova Småstuen, M.; Hovde, Ø.; Jelsness-Jørgensen, L.P.; Moum, B. Risk of Cancer in Patients With Crohn’s Disease 30 Years After Diagnosis (the IBSEN Study). Crohn’s Colitis 360 2023, 5, otad057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, B.; Pasharavesh, L.; Sharifian, A.; Zali, M.R. Concurrent inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis: A review of pre- and post-transplant outcomes and treatment options. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2023, 16, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puca, P.; Del Vecchio, L.E.; Ainora, M.E.; Gasbarrini, A.; Scaldaferri, F.; Zocco, M.A. Role of Multiparametric Intestinal Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Response to Biologic Therapy in Adults with Crohn’s Disease. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Colombel, J.F.; Sandborn, W.J. The natural history of adult Crohn’s disease in population-based cohorts. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Rutter, M.D.; Askari, A.; Lee, G.H.; Warusavitarne, J.; Moorghen, M.; Thomas-Gibson, S.; Saunders, B.P.; Graham, T.A.; Hart, A.L. Forty-Year Analysis of Colonoscopic Surveillance Program for Neoplasia in Ulcerative Colitis: An Updated Overview. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, C.; Abrams, K.R.; Mayberry, J. Meta-analysis: Colorectal and small bowel cancer risk in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 23, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Karpiński, P.; Sąsiadek, M.M. Transcriptomic Profiling for the Autophagy Pathway in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Pietrocola, F.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Cecconi, F.; Codogno, P.; Debnath, J.; Gewirtz, D.A.; Karantza, V.; et al. Autophagy in malignant transformation and cancer progression. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 856–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, N. A brief history of autophagy from cell biology to physiology and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzych, K.R.; Klionsky, D.J. An overview of autophagy: Morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Emr, S.D. Autophagy as a regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science 2000, 290, 1717–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Gou, W.F.; Zhao, S.; Xiao, L.-J.; Mao, X.-Y.; Xing, Y.-N.; Takahashi, H.; Takano, Y.; Zheng, H.-C. Beclin 1 expression is an independent prognostic factor for gastric carcinomas. Tumour Biol. 2013, 34, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Jia, S.N.; Yang, F.; Jia, W.-H.; Yu, X.-J.; Yang, J.-S.; Yang, W.-J. The transcription factor p8 regulates autophagy during diapause embryo formation in Artemia parthenogenetica. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, L. Autophagy is a double-edged sword in the therapy of colorectal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, M.; Zmarzły, N.; Grabarek, B.; Mazurek, U.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M. Genes involved in the regulation of different types of autophagy and their participation in cancer pathogenesis. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 34413–34428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bednarczyk, M.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M.; Dzięgielewska-Gęsiak, S.; Fatyga, E.; Waniczek, D. Transcription of Autophagy Associated Gene Expression as Possible Predictors of a Colorectal Cancer Prognosis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bednarczyk, M.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M.; Dzięgielewska-Gęsiak, S.; Waniczek, D. Relationship between the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Autophagy in Colorectal Cancer Tissue. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bednarczyk, M.; Fatyga, E.; Dzięgielewska-Gęsiak, S.; Waniczek, D.; Grabarek, B.; Zmarzły, N.; Janikowska, G.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M. The Expression Patterns of BECN1, LAMP2, and PINK1 Genes in Colorectal Cancer Are Potentially Regulated by Micrornas and CpG Islands: An In Silico Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, M.M.; Lo, C.H.; Wang, K.; Polychronidis, G.; Wang, L.; Zhong, R.; Knudsen, M.D.; Fang, Z.; Song, M. Immune-Mediated Diseases Associated With Cancer Risks. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carchman, E. Crohn’s Disease and the Risk of Cancer. Clin. Colon Rectal. Surg. 2019, 32, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.R.; Al Bakir, I.; Ding, N.J.; Lee, G.-H.; Askari, A.; Warusavitarne, J.; Moorghen, M.; Humphries, A.; Ignjatovic-Wilson, A.; Thomas-Gibson, S.; et al. Cumulative burden of inflammation predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in ulcerative colitis: A large single-centre study. Gut 2019, 68, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shen, J.; Ran, Z. Emerging views of mitophagy in immunity and autoimmune diseases. Autophagy 2020, 16, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okai, N.; Watanabe, T.; Minaga, K.; Kamata, K.; Honjo, H.; Kudo, M. Alterations of autophagic and innate immune responses by the Crohn’s disease-associated ATG16L1 mutation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 3063–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Wang, S.; Tan, X.; Wang, D. New Insights into the Mechanisms of Chaperon-Mediated Autophagy and Implications for Kidney Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramjeet, M.; Hussey, S.; Philpott, D.J.; Travassos, L.H. ‘Nodophagy’: New crossroads in Crohn disease pathogenesis. Gut Microbes 2010, 1, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, G.G. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgens, M.W.; van Oijen, M.G.; van der Heijden, G.J.; Vleggaar, F.P.; Siersema, P.D.; Oldenburg, B. Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: An updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.M.M.; Towers, C.G.; Thorburn, A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi, S.; Mansoori, B.; Taeb, S.; Sadeghi, H.; Abbasi, R.; Cho, W.C.; Rostamzadeh, D. mTOR-Mediated Regulation of Immune Responses in Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 774103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferro, F.; Servais, S.; Besson, P.; Roger, S.; Dumas, J.F.; Brisson, L. Autophagy and mitophagy in cancer metabolic remodelling. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 98, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Fang, X.; Wang, X. Autophagy and inflammation. Clin. Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; He, S.; Ma, B. Autophagy and autophagy-related proteins in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, J.; Gammoh, N.; Ryan, K.M. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, T.; Richly, H. Autophagy during ageing—From Dr Jekyll to Mr Hyde. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Goding Sauer, A.; Fedewa, S.A.; Butterly, L.F.; Anderson, J.C.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaukat, A.; Kahi, C.J.; Burke, C.A.; Rabeneck, L.; Sauer, B.G.; Rex, D.K. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Colorectal Cancer Screening 2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadwell, K.; Liu, J.Y.; Brown, S.L.; Miyoshi, H.; Loh, J.; Lennerz, J.K.; Kishi, C.; Kc, W.; Carrero, J.A.; Hunt, S.; et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature 2008, 456, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foerster, E.G.; Mukherjee, T.; Cabral-Fernandes, L.; Rocha, J.D.; Girardin, S.E.; Philpott, D.J. How autophagy controls the intestinal epithelial barrier. Autophagy 2022, 18, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaser, A.; Zeissig, S.; Blumberg, R.S. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 28, 573–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aita, V.M.; Liang, X.H.; Murty, V.V.; Pincus, D.L.; Yu, W.; Cayanis, E.; Kalachikov, S.; Gilliam, T.; Levine, B. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics 1999, 59, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, K.B.; Chen, W.; Mai, J.; Wu, X.-Q.; Sun, T.; Wu, R.-Y.; Jiao, L.; Li, D.-D.; Ji, J.; et al. CUL3 (cullin 3)-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of BECN1 (beclin 1) inhibit autophagy and promote tumor progression. Autophagy 2021, 17, 4323–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laddha, S.V.; Ganesan, S.; Chan, C.S.; White, E. Mutational landscape of the essential autophagy gene BECN1 in human cancers. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.B.; Hou, J.H.; Feng, X.Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cai, M. Decreased expression of Beclin 1 correlates with a metastatic phenotypic feature and adverse prognosis of gastric carcinomas. J. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 105, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Min, Y.; Jeong, S.K.; Son, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, D.-H.; Lee, J.S.; Chun, E.; Lee, K.-Y. USP15 negatively regulates lung cancer progression through the TRAF6-BECN1 signaling axis for autophagy induction. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, S.; Gou, W.F.; Xiao, L.-J.; Takano, Y.; Zheng, H.-C. Aberrant Beclin 1 expression is closely linked to carcinogenesis, differentiation, progression, and prognosis of ovarian epithelial carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2014, 35, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Mentrup, H.L.; Novak, E.A.; Siow, V.S.; Wang, Q.; Crawford, E.C.; Schneider, C.; Comerford, T.E.; Firek, B.; Rogers, M.B.; et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase contributes to epithelial homeostasis in intestinal inflammation via Beclin-1-mediated autophagy. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, X. Expression of Beclin1 in the colonic mucosa tissues of patients with ulcerative colitis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 21098–21105. [Google Scholar]

- Galandiuk, S.; Rodriguez-Justo, M.; Jeffery, R.; Nicholson, A.M.; Cheng, Y.; Oukrif, D.; Elia, G.; Leedham, S.J.; McDonald, S.A.; Wright, N.A.; et al. Field cancerization in the intestinal epithelium of patients with Crohn’s ileocolitis. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 855–864.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Schardey, J.; Zhang, T.; Crispin, A.; Wirth, U.; Karcz, K.W.; Bazhin, A.V.; Andrassy, J.; Werner, J.; Kühn, F. Survival Outcomes and Clinicopathological Features in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-associated Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 2022, 276, e319–e330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olén, O.; Erichsen, R.; Sachs, M.C.; Pedersen, L.; Halfvarson, J.; Askling, J.; Ekbom, A.; Sørensen, H.T.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Colorectal cancer in Crohn’s disease: A Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Gou, W.F.; Zhao, S.; Mao, X.Y.; Zheng, Z.H.; Takano, Y.; Zheng, H.C. Beclin 1 Expression is Closely Linked to Colorectal Carcinogenesis and Distant Metastasis of Colorectal Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 14372–14385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.C.; Kim, S.; Peng, W.; Krainc, D. Regulation and Function of Mitochondria-Lysosome Membrane Contact Sites in Cellular Homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, M.; Yamano, K.; Sato, M.; Matsuda, N.; Okamoto, K. Molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of mitophagy. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larabi, A.; Barnich, N.; Nguyen, H.T.T. New insights into the interplay between autophagy, gut microbiota and inflammatory responses in IBD. Autophagy 2020, 16, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetto, M.G.; Ossani, G.; Monserrat, A.J.; Boveris, A. Oxidative damage: The biochemical mechanism of cellular injury and necrosis in choline deficiency. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2010, 88, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wu, W.; Jiang, S.; Yu, S.; Yan, Y.; Wang, K.; He, J.; Ren, Y.; Wang, B. Pan-Cancer Analysis of the Mitophagy-Related Protein PINK1 as a Biomarker for the Immunological and Prognostic Role. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 569887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolina, N.; Bruton, J.; Kostareva, A.; Sejersen, T. Assaying Mitochondrial Respiration as an Indicator of Cellular Metabolism and Fitness. In Cell Viability Assays. Methods in Molecular Biology; Gilbert, D., Friedrich, O., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1601, pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, L.E.; Springer, M.Z.; Poole, L.P.; Kim, C.J.; Macleod, K.F. Expanding perspectives on the significance of mitophagy in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2017, 47, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, F.; Sina, C.; Hundorfean, G.; Pagel, R.; Lehnert, H.; Fellermann, K.; Büning, J. Inflammatory bowel diseases influence major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC I) and II compartments in intestinal epithelial cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013, 172, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Lee, J.; Liu, Z.; Kim, H.; Martin, D.R.; Wu, D.; Liu, M.; Xue, X. Mitophagy protein PINK1 suppresses colon tumor growth by metabolic reprogramming via p53 activation and reducing acetyl-CoA production. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 2421–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Yuan, H.; Zhu, S.; Liu, J.; Wen, Q.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Kroemer, G.; et al. PINK1 and PARK2 Suppress Pancreatic Tumorigenesis through Control of Mitochondrial Iron-Mediated Immunometabolism. Dev. Cell 2018, 46, 441–455.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Krüger, U.; Kaushik, S.; Wong, E.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Cuervo, A.M.; Mandelkow, E. Tau fragmentation, aggregation and clearance: The dual role of lysosomal processing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 4153–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, J.N.; Lu, H.H.; Chiang, H.Y.; Suen, C.S.; Hwang, M.J.; Wu, S.Y.; Shen, C.N.; Chang, Y.M.; Li, F.A.; Liu, F.T.; et al. Lumenal Galectin-9-Lamp2 interaction regulates lysosome and autophagy to prevent pathogenesis in the intestine and pancreas. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Luo, X.; Schefczyk, S.; Muungani, L.T.; Deng, H.; Wang, B.; Baba, H.A.; Lu, M.; Wedemeyer, H.; Schmidt, H.H.; et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen expression impairs endoplasmic reticulum stress-related autophagic flux by decreasing LAMP2. JHEP Rep. 2024, 6, 101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Veiga, T.; Bravo, S.; Gómez-Tato, A.; Yáñez-Gómez, C.; Abuín, C.; Varela, V.; Cueva, J.; Palacios, P.; Dávila-Ibáñez, A.B.; Piñeiro, R.; et al. Red Blood Cells Protein Profile Is Modified in Breast Cancer Patients. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2022, 21, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Yang, S.; Shen, C.; Shao, J.; Zhou, F.; Liu, H.; Zhou, G. LAMP2A regulates cisplatin resistance in colorectal cancer through mediating autophagy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 2421–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tao, K. Deficient chaperone-mediated autophagy in macrophages aggravates colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis in mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 2025, 240, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Muller, S. Manipulating autophagic processes in autoimmune diseases: A special focus on modulating chaperone-mediated autophagy, an emerging therapeutic target. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.L. Consistent across-tissue signatures of differential gene expression in Crohn’s disease. Immunogenetics 2005, 57, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Cuervo, A.M. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: A unique way to enter the lysosome world. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.L.; Cuervo, A.M. Autophagy and human disease: Emerging themes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2014, 26, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xiao, X.; Xiang, L.; Zheng, H.C. Inhibition of chaperone-mediated autophagy reduces tumor growth and metastasis and promotes drug sensitivity in colorectal cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, M.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M.; Waniczek, D.; Fatyga, E.; Klakla, K.; Mazurek, U.; Wierzgoń, J. Autophagy-related gene expression in colorectal cancer patients. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Meng, Z.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J. ATG7-induced autophagy inhibits ferroptosis and promotes the progression of colorectal adenocarcinoma. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, A.; Duan, W.; Li, Y.; Kong, X.; Wang, T.; Niu, D.; Liu, S.; Zhang, P.; Wang, C.; et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 48 drives malignant progression of colorectal cancer by suppressing autophagy through stabilizing sequestosome 1. Cell Death Differ. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jin, L.; Wan, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Shen, G.; Gong, J.; Zhu, Y. TIPE3 promotes drug resistance in colorectal cancer by enhancing autophagy via the USP19/Beclin1 pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, C.; Castiglioni, A.; Walusimbi, U.; Vidoni, C.; Ferraresi, A.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Isidoro, C. The Biological Role and Clinical Significance of BECLIN-1 in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | CD Group n = 48 | CRC Group n = 87 | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | Q1 | Q3 | Median | Range | Q1 | Q3 | ||

| Age [y] | 43.5 | 22–78 | 31.0 | 58.5 | 68.0 | 41–82 | 59.0 | 73.0 | 0.0001 |

| Height [m] | 1.70 | 1.54–1.94 | 1.63 | 1.77 | 1.66 | 1.54–1.88 | 1.56 | 1.76 | n.s. |

| Body mass [kg] | 62.0 | 35–107 | 56.5 | 72.5 | 76.0 | 45–105 | 63.0 | 87.0 | 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.85 | 13.5–28.43 | 19.42 | 24.20 | 26.45 | 18.17–36.73 | 24.45 | 29.50 | 0.0001 |

| Ht [%] | 36.1 | 25.1–47.4 | 30.4 | 40.5 | 37.9 | 27.2–47.8 | 36.2 | 40.1 | n.s. |

| WBC [M] | 7.12 | 3.60–25.1 | 4.84 | 9.67 | 6.56 | 2.90–15.76 | 5.09 | 8.37 | n.s. |

| Gender | CD Group | CRC Group | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Female | 28 | 58.0 | 36 | 41.4 | n.s. |

| Male | 20 | 42.0 | 51 | 58.6 | n.s. |

| Cancer Stage | Number of Cases | % |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 22 | 25.3 |

| Stage II | 20 | 23.0 |

| Stage III | 33 | 37.9 |

| Stage IV | 12 | 13.8 |

| Total | 87 | 100.0 |

| Gene | Primer Sequences 5′ → 3′ (Forward) | Primer Sequences 5′ → 3′ (Reverse) |

|---|---|---|

| BECN1 | CAGTATCAGAGAGAATACAGTG | TGGAAGGTTGCATTAAAGAC |

| LAMP-2 | AACAAAGAGCAGACTGTTTC | CAGCTGTAGAATACTTTCCTTG |

| PINK1 | TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACC |

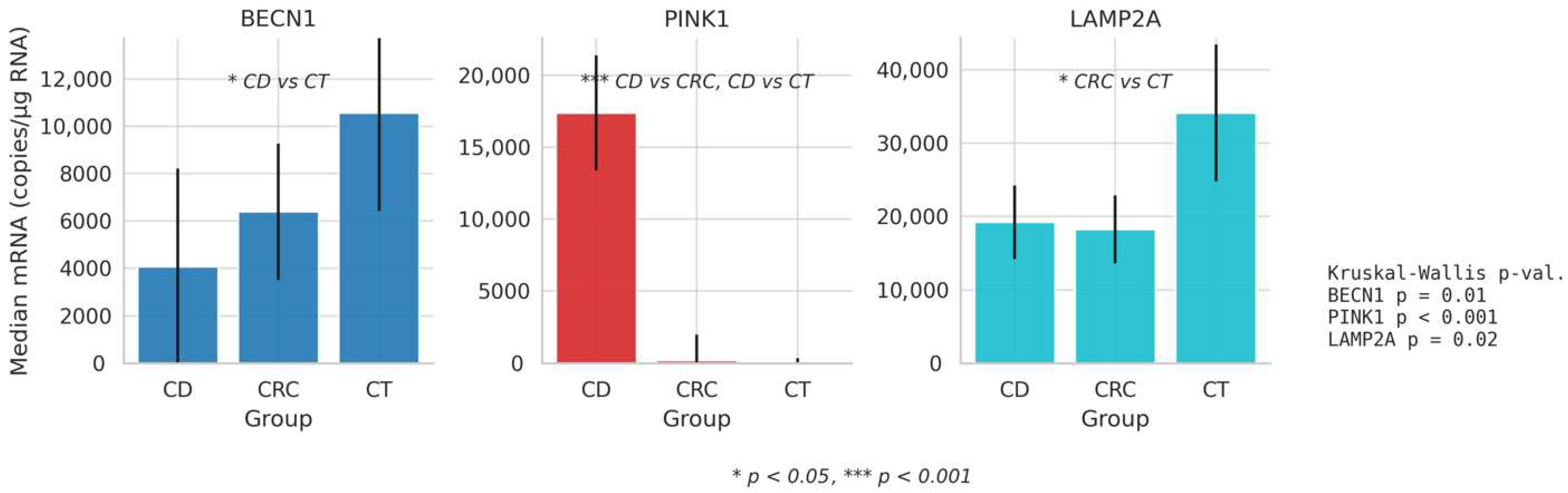

| Group/mRNA Molecules | Mean × 106 | Median | SD × 106 | Min | Max × 106 | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | BECN1 | 0.01158 | 4062 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.093 | 16,610 |

| PINK1 | 1.40416 | 17,380 | 13.6 | 84.00 | 133.3 | 6388 | |

| LAMP2 | 13,524.6 | 19,215 | 43,398.0 | 0.42 | 262,500 | 20,054 | |

| CRC | BECN1 | 11,074.5 | 6388 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.0933 | 11,529 |

| PINK1 | 1372.30 | 194 | 6793.4 | 0.00 | 47,380 | 7198 | |

| LAMP2 | 1.43173 | 18,250 | 13.12 | 857.0 | 122.4 | 18,540 | |

| CT | BECN1 | 8.53022 | 10,560 | 57.6062 | 0.15 | 453.9 | 16,532 |

| PINK1 | 0.02261 | 13 | 0.17992 | 0.00 | 1.717 | 1292 | |

| LAMP2 | 3.74573 | 34,135 | 20.3783 | 5442 | 122.4 | 37,385 | |

| Gene/Group Patients | n | Mean Rank | Median | Q1 | Q3 | H | p | η2 | Post Hoc A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA Copy/μg RNA | ||||||||||

| BECN1 | CD | 96 | 121.511 | 4062.000 | 280.500 | 16,890.000 | 9.421 | 0.01 | 0.030 | CD vs. CT |

| CRC | 87 | 132.823 | 6388.000 | 1571.000 | 13,100.000 | |||||

| CT | 87 | 156.433 | 10,560.000 | 3853.000 | 20,385.000 | |||||

| PINK 1 | CD | 96 | 197.411 | 17,380.000 | 5929.000 | 21,952.000 | 89.920 | <0.001 | 0.320 | CD vs. CRC CD vs. CT |

| CRC | 87 | 119.332 | 194.000 | 0.571 | 7199.000 | |||||

| CT | 87 | 91.701 | 13.201 | 0.073 | 1292.000 | |||||

| LAMP2 | CD | 96 | 126.900 | 19,215.000 | 4596.500 | 24,650.000 | 7.540 | 0.02 | 0.020 | CRC vs. CT |

| CRC | 87 | 122.500 | 18,250.000 | 10,770.000 | 29,310.000 | |||||

| CT | 87 | 151.702 | 34,135.000 | 14,357.500 | 51,742.500 | |||||

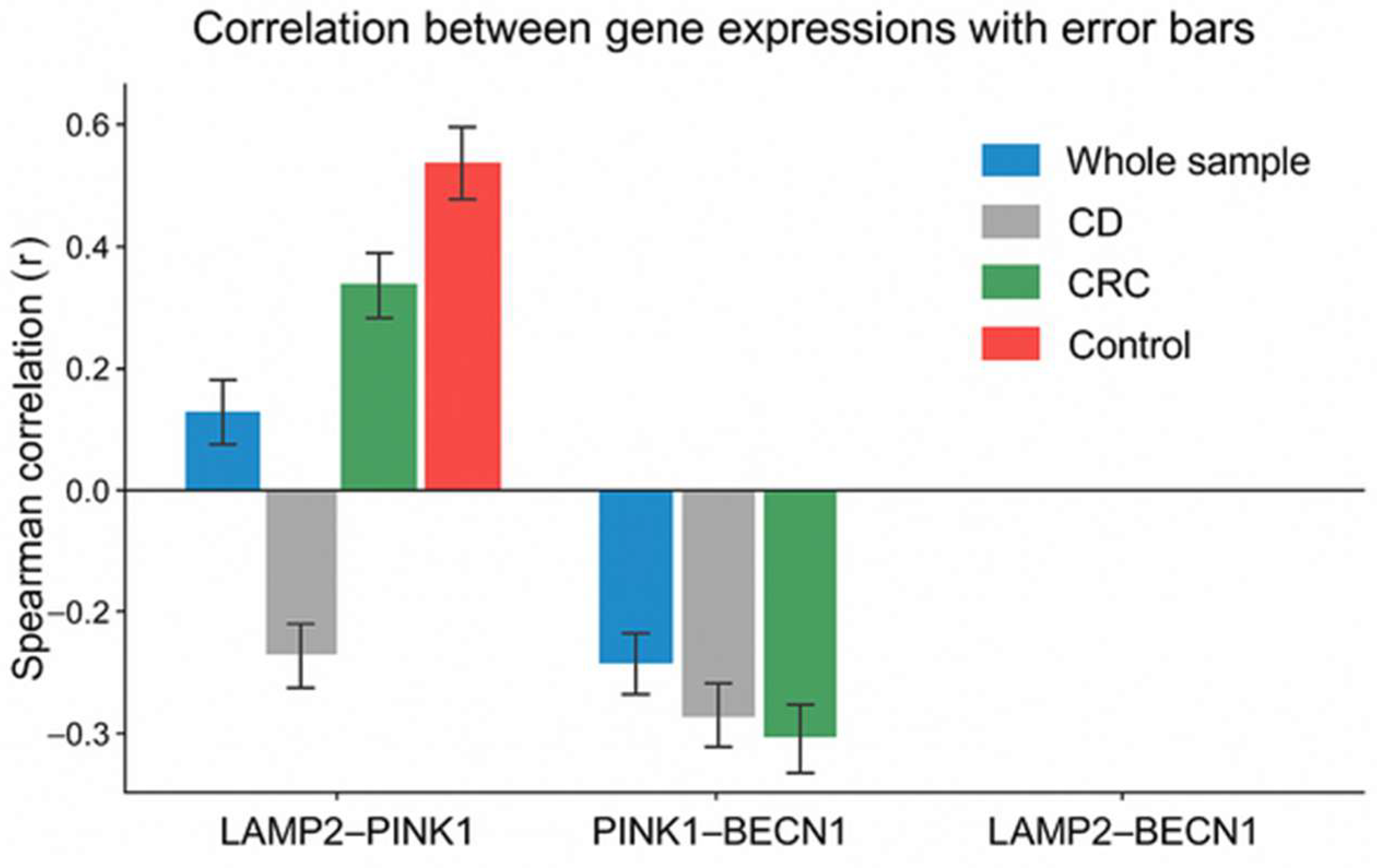

| Group/Gene Expression | LAMP2 | PINK1 | BECN1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole sample | LAMP2 | 1 | ||

| PINK1 | 0.16 ** | 1 | ||

| BECN1 | <0.01 | −0.23 ** | 1 | |

| Crohn’s disease | LAMP2 | 1 | ||

| PINK1 | 0.16 | 1 | ||

| BECN1 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 1 | |

| Colorectal cancer | LAMP2 | 1 | ||

| PINK1 | 0.28 ** | 1 | ||

| BECN1 | −0.07 | −0.24 * | 1 | |

| Control group | LAMP2 | 1 | ||

| PINK1 | 0.51 ** | 1 | ||

| BECN1 | −0.04 | −0.13 | 1 |

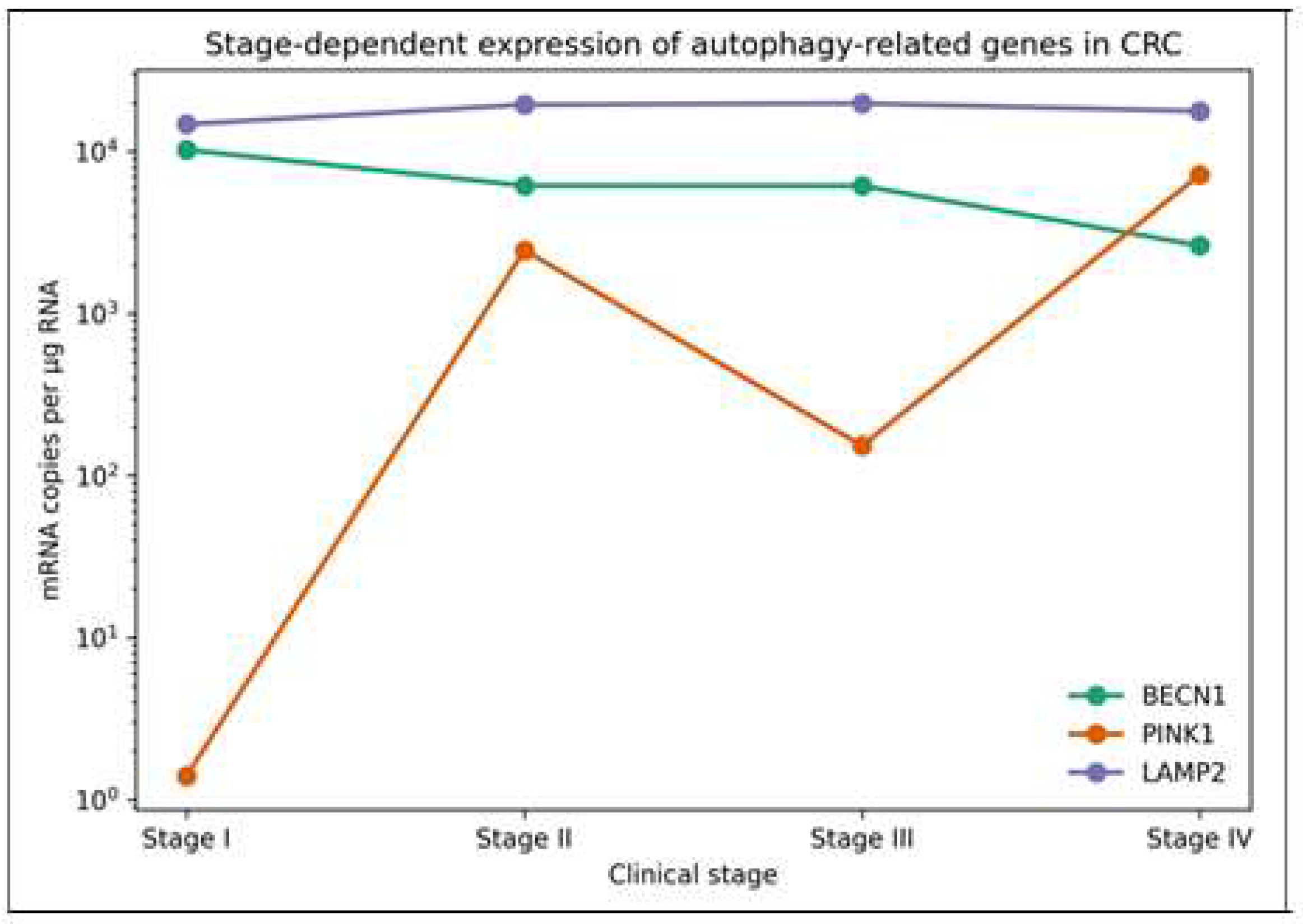

| Gene | CC Stage | n | Mean Rank | Median | Q1 | Q3 | H | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copies of RNA Per µg of Total RNA (mRNA/µg RNA) | |||||||||

| BECN1 | CSI | 22 | 50.52 | 10,245 | 3121 | 18,260 | 4.21 | 0.240 | <0.01 |

| CSII | 20 | 43.00 | 6168 | 1925 | 9297 | ||||

| CSIII | 32 | 43.22 | 6141 | 1233 | 15,448 | ||||

| CSIV | 12 | 32.21 | 2629 | 268 | 10,828 | ||||

| PINK1 | CSI | 22 | 36.14 | 1.4 | 0.17 | 1214 | 4.70 | 0.196 | 0.01 |

| CSII | 20 | 49.60 | 2458 | 3.04 | 9385 | ||||

| CSIII | 33 | 42.62 | 153 | 0.91 | 3015 | ||||

| CSIV | 12 | 52.88 | 7203 | 239.24 | 3470 | ||||

| LAMP2 | CSI | 22 | 38.68 | 14,735 | 8131 | 24,833 | 1.86 | 0.602 | <0.01 |

| CSII | 20 | 47.75 | 19,470 | 12,428 | 34,783 | ||||

| CSIII | 33 | 46.33 | 19,830 | 9097 | 48,815 | ||||

| CSIV | 12 | 41.08 | 17,775 | 14,363 | 21,498 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bichalska-Lach, M.; Waniczek, D.; Kowalczyk, P.; Śnietura, M.; Kryj, M.; Bednarczyk, M.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M. Autophagy Dysregulation in Crohn’s Disease and Colorectal Cancer—An Analysis of BECN1, PINK1, and LAMP2 Gene Expression. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010031

Bichalska-Lach M, Waniczek D, Kowalczyk P, Śnietura M, Kryj M, Bednarczyk M, Muc-Wierzgoń M. Autophagy Dysregulation in Crohn’s Disease and Colorectal Cancer—An Analysis of BECN1, PINK1, and LAMP2 Gene Expression. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleBichalska-Lach, Magda, Dariusz Waniczek, Paweł Kowalczyk, Mirosław Śnietura, Mariusz Kryj, Martyna Bednarczyk, and Małgorzata Muc-Wierzgoń. 2026. "Autophagy Dysregulation in Crohn’s Disease and Colorectal Cancer—An Analysis of BECN1, PINK1, and LAMP2 Gene Expression" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010031

APA StyleBichalska-Lach, M., Waniczek, D., Kowalczyk, P., Śnietura, M., Kryj, M., Bednarczyk, M., & Muc-Wierzgoń, M. (2026). Autophagy Dysregulation in Crohn’s Disease and Colorectal Cancer—An Analysis of BECN1, PINK1, and LAMP2 Gene Expression. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010031