DPPH Measurement for Phenols and Prediction of Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Compounds in Food

Abstract

1. Introduction

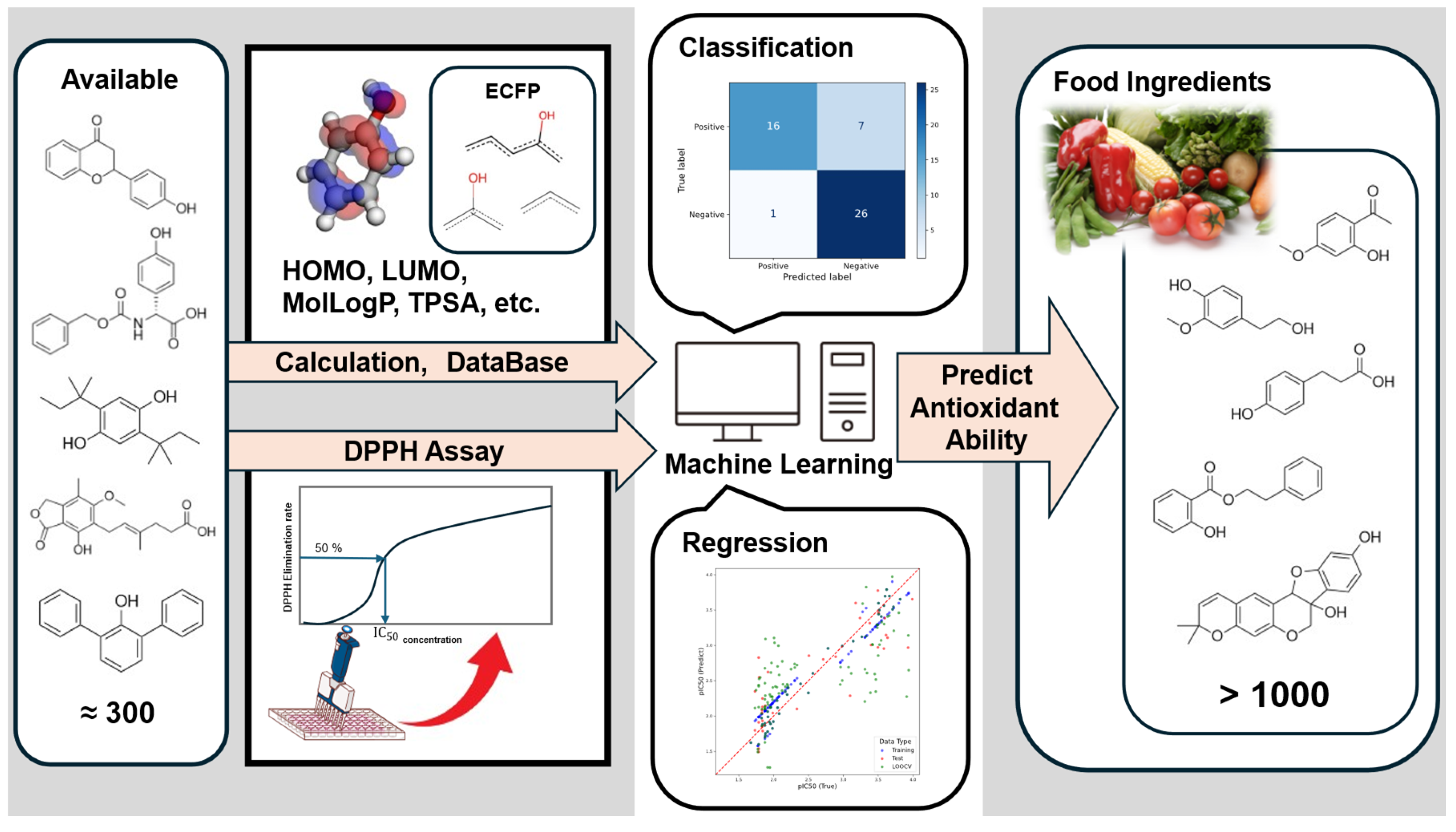

2. Materials and Methods

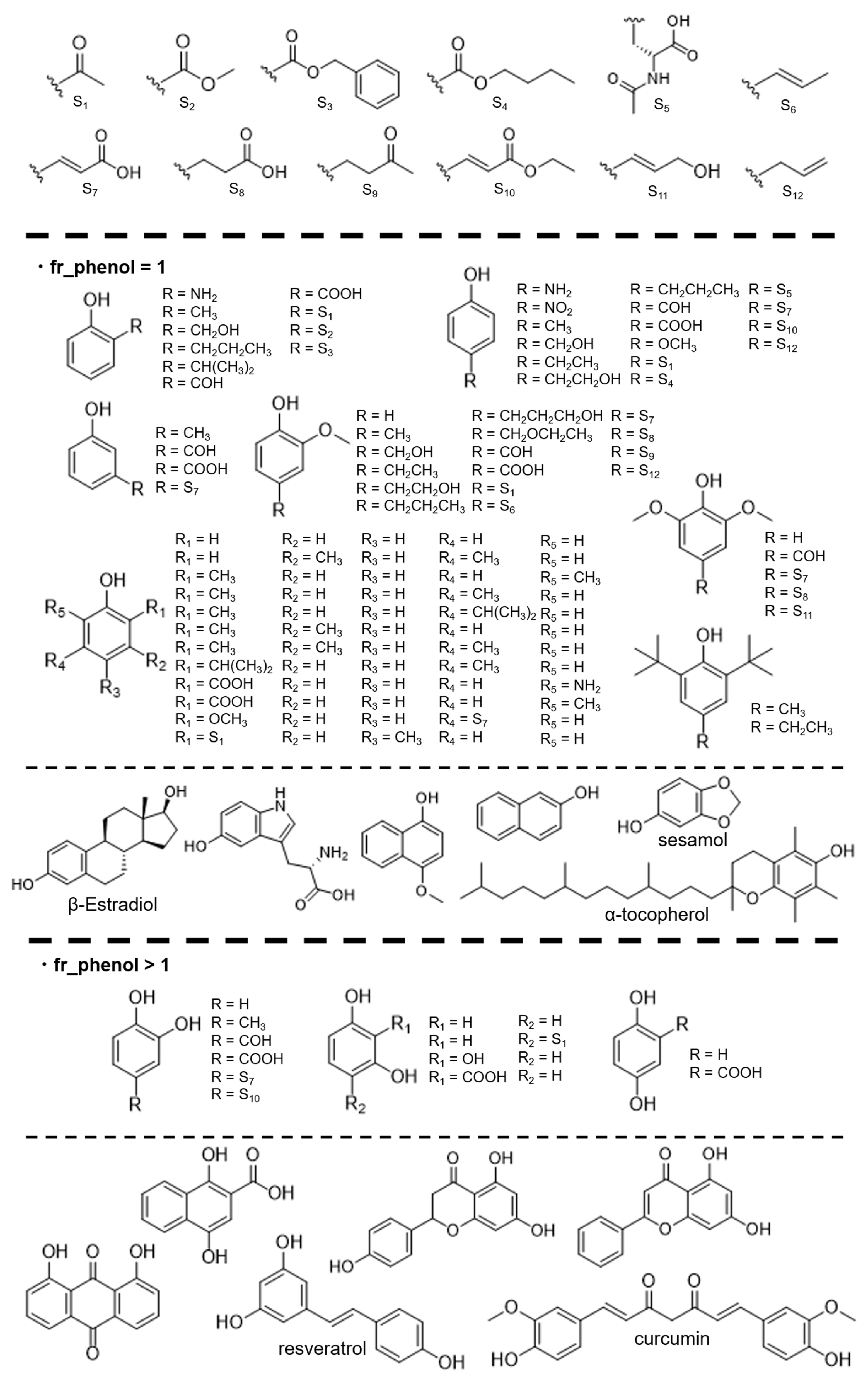

2.1. Reagents and Synthesis

2.2. DPPH Radical-Scavenging Activity Measurement

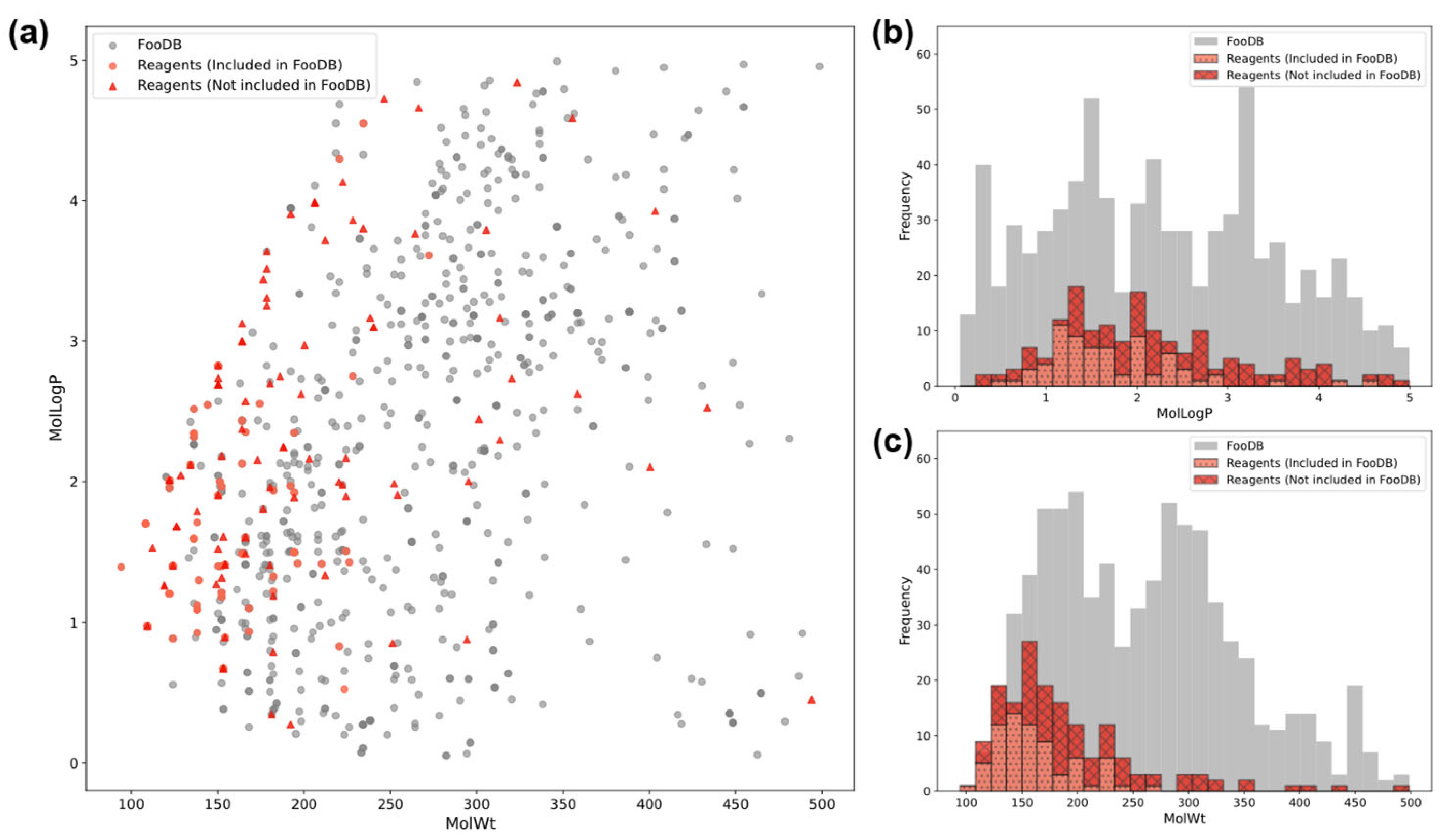

2.3. Dataset

2.4. E_HOMO_calc and E_LUMO_calc Calculations

2.5. Machine Learning

2.5.1. Calculation Descriptor

2.5.2. Classification Model

2.5.3. Regression Model

3. Results

3.1. Results of DPPH Assay

3.2. Comparison of Calculation Level

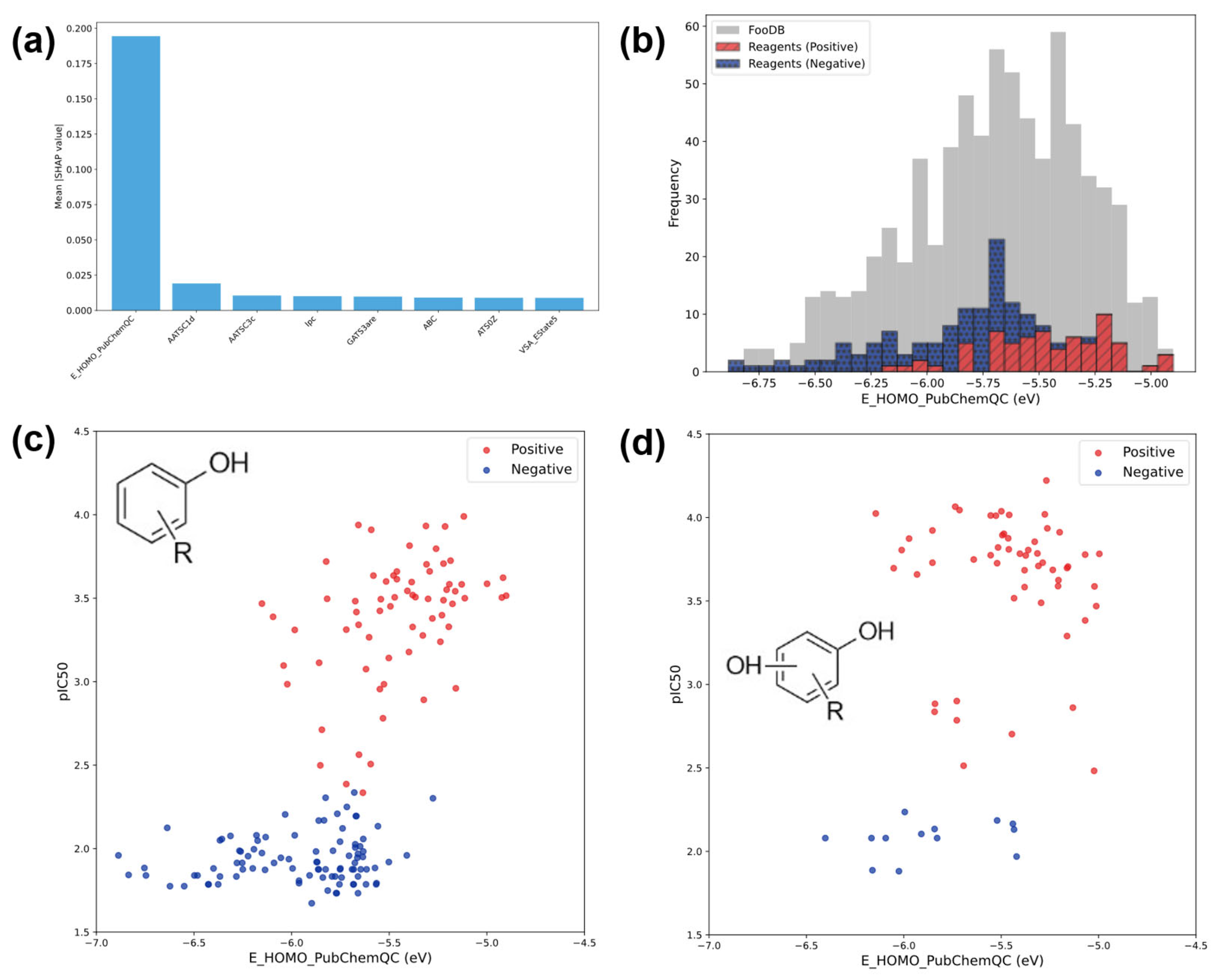

3.3. Results of Machine Learning Analysis

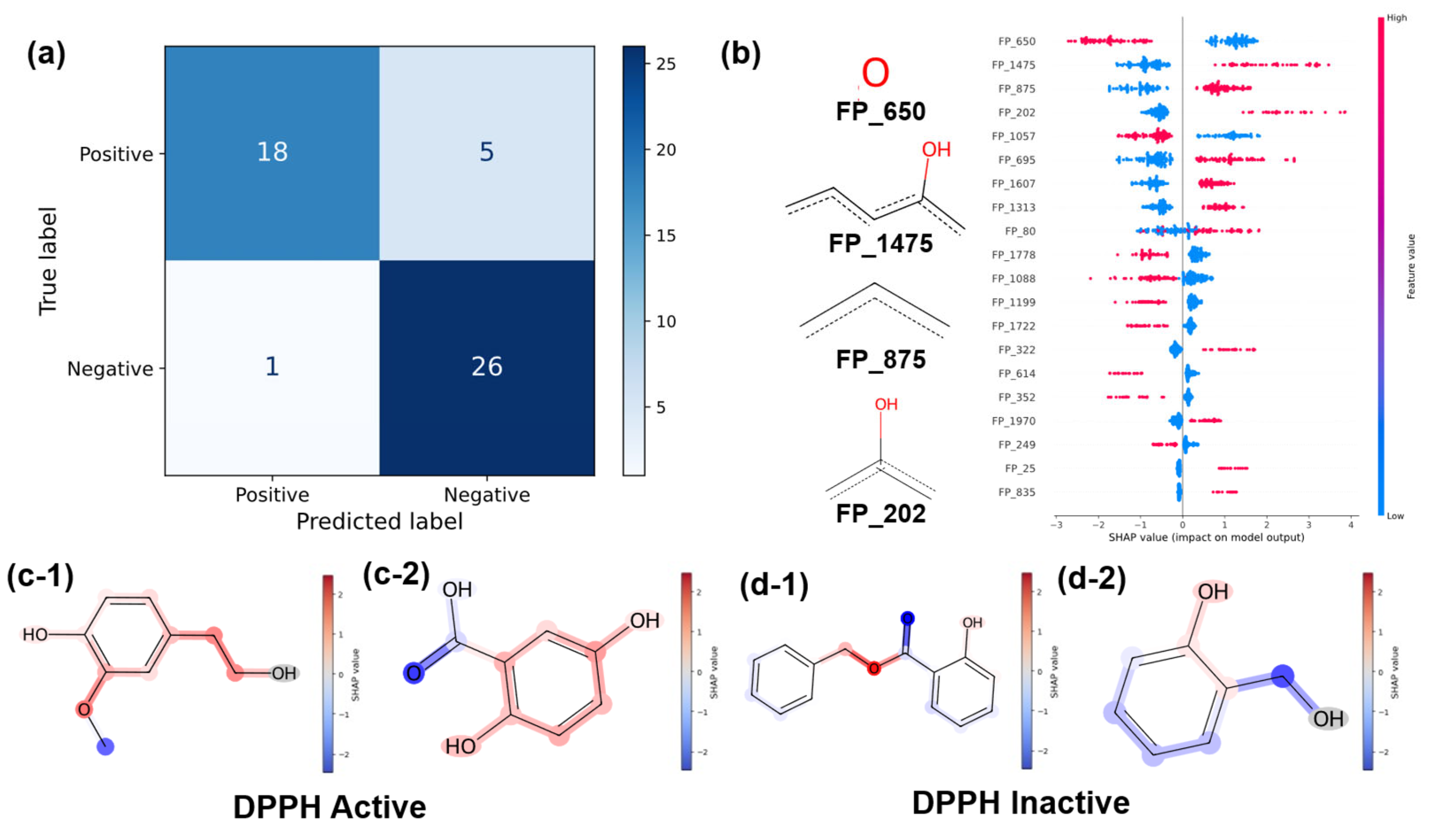

3.3.1. Classification Results

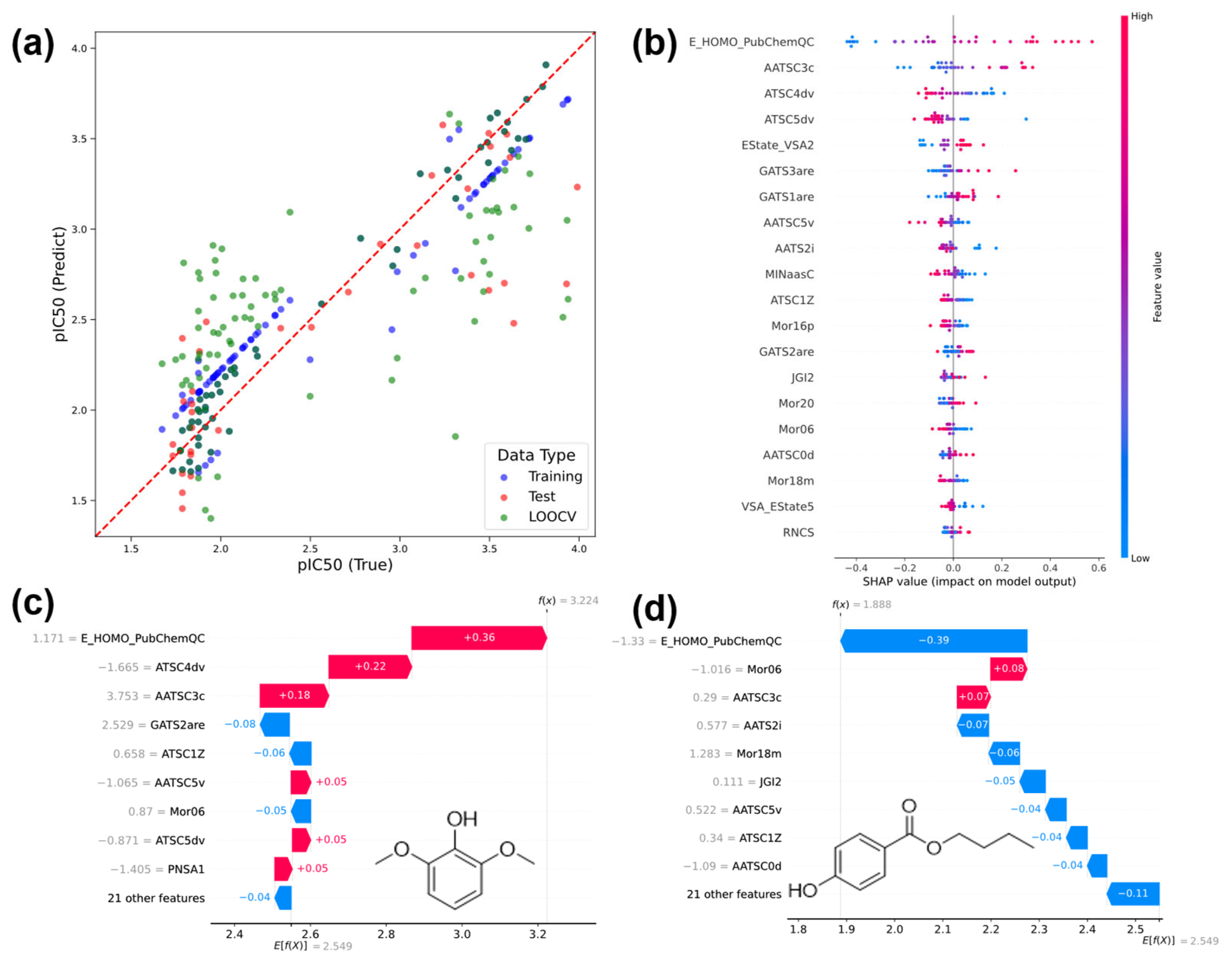

3.3.2. Regression Results

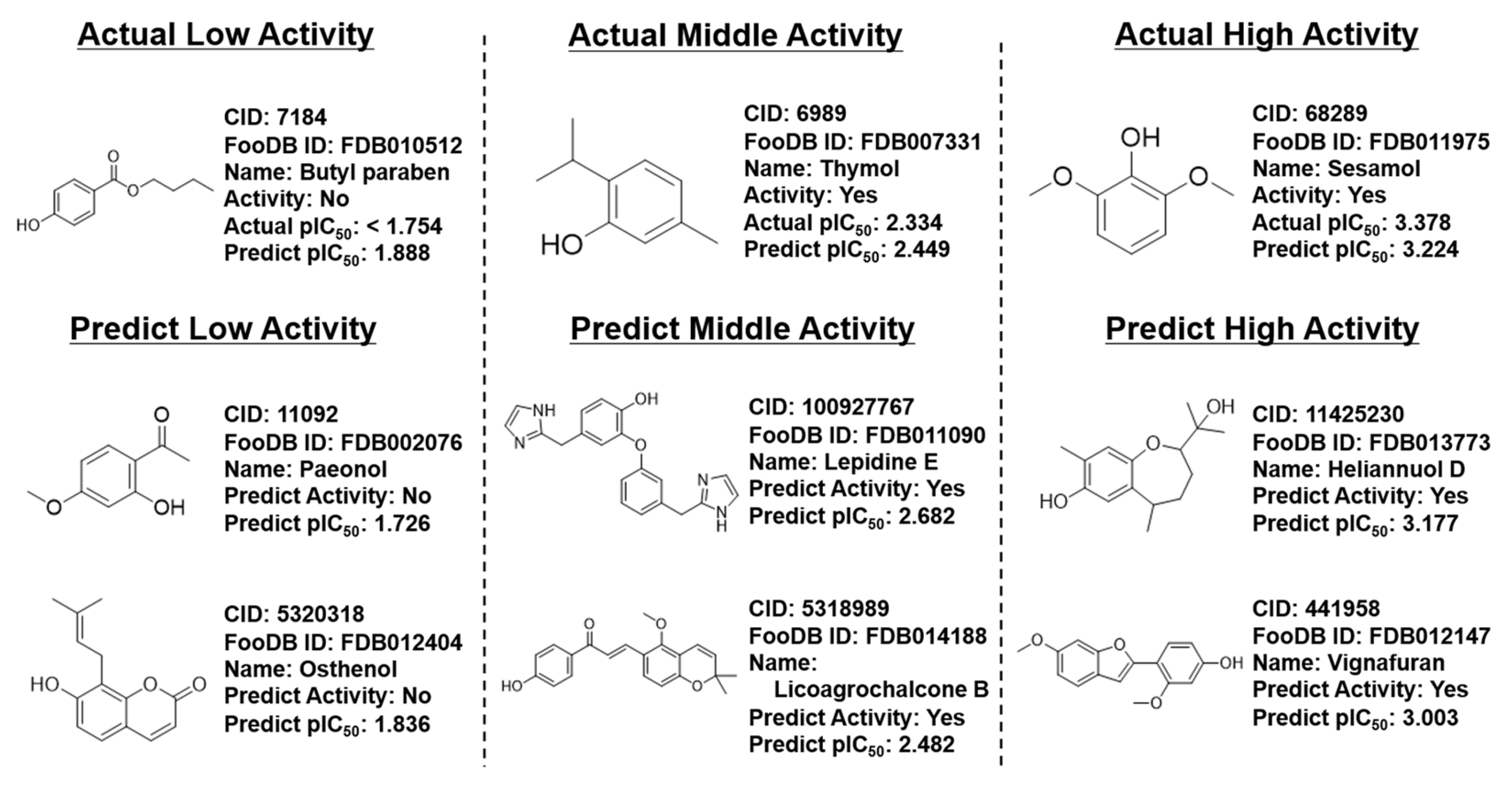

3.4. Prediction of FooDB Compounds

3.5. Limitations and Directions for Future Work

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SAR | Structure–Activity Relationship |

| IP | Ionization Potential |

| NNs | Neural Networks |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| Trolox | 6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-Tetramethyl-3,4-Dihydrochromene-2-Carboxylic Acid |

| TEAC | Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity |

| E_HOMO | Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital Energy |

| E_LUMO | Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital Energy |

| MMFF | Merck Molecular Force Field |

| TPE | Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator |

| LOOCV | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| SHAP | Shapley’s Additive Explanation |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

References

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: An updated overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 651–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, A.; Andrabi, S.S.; Mansoor, S.; Kuang, Y.; Kwon, B.K.; Labhasetwar, V. Antioxidant therapy in oxidative stress-induced neurodegenerative diseases: Role of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems in clinical translation. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants: A comprehensive review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apak, R.; Gorinstein, S.; Böhm, V.; Schaich, K.M.; Özyürek, M.; Güçlü, K. Methods of measurement and evaluation of natural antioxidant capacity/activity (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 957–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashino, I.; Mizoue, T.; Serafini, M.; Akter, S.; Sawada, N.; Ishihara, J.; Kotemori, A.; Inoue, M.; Yamaji, T.; Goto, A.; et al. Higher dietary non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity is associated with decreased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in Japanese adults. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, N.; Vitaglione, P.; Granato, D.; Fogliano, V. Twenty-five years of total antioxidant capacity measurement of foods and biological fluids: Merits and limitations. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 5064–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchmore, S.W.; Edmunds, J.J.; Stewart, K.D.; Hajduk, P.J. Cheminformatic tools for medicinal chemists. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4830–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parejo, I.; Viladomat, F.; Bastida, J.; Rosas-Romero, A.; Flerlage, N.; Burillo, J.; Codina, C. Comparison between the radical scavenging activity and antioxidant activity of six distilled and nondistilled mediterranean herbs and aromatic plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6882–6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, I. Antioxidant activity of food constituents: An overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2012, 86, 345–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Schaich, K.M. Re-Evaluation of the 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl free radical (DPPH) assay for antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4251–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monika, B.; Klaudia, S.; Vanja, T.; Barbara, K.; Wojciech, C.; Sladjana, S.; Agnieszka, B. Interactions between bioactive components determine antioxidant, cytotoxic and nutrigenomic activity of cocoa powder extract. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 154, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripti, J.; Kartik, A.; Manan, M.; Deepa, P.R.; Pankaj, K. Measurement of antioxidant synergy between phenolic bioactives in traditional food combinations (legume/non-legume/fruit) of (semi) arid regions: Insights into the development of sustainable functional foods. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsufuji, H.; Sasa, R.; Honma, Y.; Miyajima, H.; Chino, M.; Yamazaki, T.; Shimamura, T.; Ukeda, H.; Matsui, T.; Matsumoto, K.; et al. 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging activity of binary mixtures of antioxidants. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Preserv. Sci. 2009, 56, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shimamura, T. Food chemical study on verification of assay for antioxidant capacity of food additive and its application. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Preserv. Sci. 2018, 44, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Liang, J.; Lu, L.; Wang, L. Untargeted metabolomics reveals phenolic compound dynamics during mung bean fermentation. Food Chem. X 2025, 31, 103189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisa, P.; Teresa, G.; Andrea, R.; Vincenzo, L.; Stanislaw, W.; Ryszard, A.; Magdalena, K. Characterization of antioxidant and antimicrobial activity and phenolic compound profile of extracts from seeds of different Vitis species. Molecules 2023, 28, 4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushila, S. In vitro antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of Digera muricata leaves. World J. Biol. Pharm. Health Sci. 2023, 14, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, M.; Kitamura, Y.; Nagano, H.; Kawatsu, J.; Gotoh, H. DPPH measurements and structure—Activity relationship studies on the antioxidant capacity of phenols. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoudi, S.A.; Tsimidou, M.Z.; Vafiadis, A.P.; Bakalbassis, E.G. Structure−DPPH• scavenging activity relationships: Parallel study of catechol and guaiacol acid derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5763–5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, O.; Durand, E.; Baréa, B.; Dauguet, S.; Fine, F.; Villeneuve, P.; Lecomte, J. Synthesis and evaluation of antioxidant activities of novel Hydroxyalkyl esters and Bis-Aryl esters based on sinaptic and caffeic acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 9308–9318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, M.; Hoshi, M.; Urano, S.; Endo, T. Antioxidant activity of eugenol and related monomeric and dimeric compounds. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 1467–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawidowicz, A.L.; Olszowy, M.; Jóźwik-Dolęba, M. Importance of solvent association in the estimation of antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds by the DPPH method. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 4523–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrum, G.A.; Riniker, S. Combining IC50 or Ki values from different sources is a source of significant noise. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimamura, T.; Matsuura, R.; Tokuda, T.; Sugimoto, N.; Yamazaki, T.; Matsufuji, H.; Matsui, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Ukeda, H. Comparison of Conventional Antioxidants Assays for Evaluating Potencies of Natural Antioxidants as Food Additives by Collaborative Study. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 54, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamura, T.; Sumikura, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Tada, A.; Kashiwagi, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Matsui, T.; Sugimoto, N.; Akiyama, H.; Ukeda, H. Applicability of the DPPH assay for evaluating the antioxidant capacity of food additives—Inter-laboratory evaluation study. Anal. Sci. 2014, 30, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, D.; Uchiyama, H.; Higashi, H.; Kida, H.; IwaiI, A. Effects of heat degradation of betanin in red beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) on biological activity and antioxidant capacity. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofian, F.F.; Kikuchi, N.; Koseki, T.; Kanno, Y.; Uesugi, S.; Shiono, Y. Antioxidant p-terphenyl compound, isolated from edible mushroom Boletopsis leucomelas. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2022, 86, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harunari, E.; Imada, C.; Igarashi, Y. Konamycins A and B and rubromycins CA1 and CA2, aromatic polyketides from the tunicate-derived Streptomyces hyaluromycini MB-PO13T. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Sun, L.; Wang, F.; Fei, N.; Nawaz, H.; Yamashita, K.; Cai, Y.; Anwar, F.; Khan, M.Q.; Mayakrishnan, G.; et al. Eco-friendly bioactive β-caryophyllene/halloysite nanotubes loaded nanofibrous sheets for active food packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 35, 101028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaño, D.; Fernández-Pachón, M.S.; Moyá, M.L.; Troncoso, A.M.; García-Parrilla, M.C. Radical scavenging ability of polyphenolic compounds towards DPPH free radical. Talanta 2007, 71, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, N.; Ayranci, G.; Ayranci, E. Antioxidant activities of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extract, blackseed (Nigella sativa L.) essential oil, carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid, and sesamol. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, M.; Kitamura, Y.; Tada, C.; Kato, R.; Gotoh, H. Kinetic and thermodynamic evaluation of antioxidant reactions: Factors influencing the radical scavenging properties of phenolic compounds in foods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 8186–8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Deng, H.; Yan, H.; Zhong, R. An accurate nonlinear QSAR model for the antitumor activities of chloroethylnitrosoureas using neural networks. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2011, 29, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Zhou, W.; Wang, L. Highly accurate and explainable predictions of small-molecule antioxidants for eight in vitro assays simultaneously through an alternating multitask learning strategy. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 9098–9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, N.; Shibata, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Taguchi, H.; Sawada, R.; Goto, K.; Momokita, S.; Aoyagi, M.; Hirao, T.; Yamanishi, Y. Revealing comprehensive food functionalities and mechanisms of action through machine learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 5712–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, T.; Gotoh, H. Prediction and chemical interpretation of singlet-oxygen-scavenging activity of small molecule compounds by using machine learning. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Hamada, S.; Goto, H. Validation study of QSAR/DNN models using the competition datasets. Mol. Inform. 2020, 39, 1900154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, E.G.; Rayar, A.M.; Barigye, S.J.; Rodríguez, M.E.J.; Veitía, M.S.I. Development of an in silico model of DPPH• free radical scavenging capacity: Prediction of antioxidant activity of coumarin type compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.; Ojima, I.; Samaras, D.; Wang, F. A systematic study of key elements underlying molecular property prediction. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagopalan, A.; Zhang, H.; Hamidieh, K.; Hartvigsen, T.; Rudzicz, F.; Ghassemi, M. The road to explainability is paved with bias: Measuring the fairness of explanations. ACM Int. Conf. Proc. Ser. 2022, 22, 1194–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagade, P.M.; Adiga, S.P.; Park, M.S.; Pandian, S.; Hariharan, K.S.; Kolake, S.M. Empirical relationship between chemical structure and redox properties: Mathematical expressions connecting structural features to energies of frontier orbitals and redox potentials for organic molecules. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 11322–11333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FooDB. Available online: https://foodb.ca/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Nishii, T.; Ichizawa, K.; Nagano, H.; Mukai, H.; Sakaguchi, D.; Gotoh, H. Predicting substrate reactivity in oxidative homocoupling of phenols using positive and unlabeled machine learning. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 49805–49815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antioxidant Ability Assay DPPH Antioxidant Assay Kit Dojindo. Available online: https://www.dojindo.com/JP-EN/products/D678/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- RDKit. Available online: https://www.rdkit.org/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Nakata, M.; Maeda, T. PubChemQC B3LYP/6-31G*//PM6 Data Set: The electronic structures of 86 million molecules using B3LYP/6-31G* Calculations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 5734–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Riniker, S.; Landrum, G.A. Better informed distance geometry: Using what we know to improve conformation generation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 2562–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halgren, T.A. Merck molecular force field. I. Basis, form, scope, parameterization, and performance of MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 490–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16; Revision A; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, H.; Tian, Y.S.; Kawashita, N.; Takagi, T. Mordred: A molecular descriptor calculator. J. Cheminform. 2018, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.; Hahn, M. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 25 July 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bardenet, R.; Bengio, Y.; Kégl, B. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process Syst. 2011, 24, 2546–2554. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, A.P. The use of the area under the roc curve in the evaluation of machine learning algorithms. Pattern Recognit. 1997, 30, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4766–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keany, E. BorutaShap: A wrapper feature selection method which combines the boruta feature selection algorithm with shapley values. (Version 1.1) [Software]. Zenodo 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Vlocskó, R.B.; Mastyugin, M.; Török, B.; Török, M. Correlation of physicochemical properties with antioxidant activity in phenol and thiophenol analogues. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Shahzad, N.; Kim, C.K. Structure-antioxidant activity relationship of methoxy, phenolic hydroxyl, and carboxylic acid groups of phenolic acids. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2611, Correction in Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5666. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62493-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbraikh, A.; Tropsha, A. Beware of q2! J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2002, 20, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, B.D.; Kerrihard, A.L.; Amarowicz, R.; Pegg, R.B. Phenol-based antioxidants and the in vitro methods used for their assessment. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012, 11, 148–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xue, Z.Q.; Liu, W.M.; Wu, J.L.; Yang, Z.Q. Koopmans’ theorem for large molecular systems within density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 12005–12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, K.; Sasada, R.; Chiba, K.; Gotoh, H. Effect of side chain functional groups on the DPPH radical scavenging activity of bisabolane-type phenols. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kato, R.; Tada, C.; Yamauchi, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; Gotoh, H. DPPH Measurement for Phenols and Prediction of Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Compounds in Food. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010012

Kato R, Tada C, Yamauchi M, Matsumoto Y, Gotoh H. DPPH Measurement for Phenols and Prediction of Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Compounds in Food. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKato, Riku, Chihiro Tada, Moeka Yamauchi, Yuto Matsumoto, and Hiroaki Gotoh. 2026. "DPPH Measurement for Phenols and Prediction of Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Compounds in Food" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010012

APA StyleKato, R., Tada, C., Yamauchi, M., Matsumoto, Y., & Gotoh, H. (2026). DPPH Measurement for Phenols and Prediction of Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Compounds in Food. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010012