SGPP2 Ameliorates Chronic Heart Failure by Attenuating ERS via the SIRT1/AMPK Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

2.2. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

2.3. Functional Enrichment Analysis (FEA) and Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Analysis

2.4. Machine Learning (ML) Analysis

2.5. Single-Cell Analysis

2.6. Immune Infiltration Analysis

2.7. Single-Gene Enrichment Analysis (SGEA)

2.8. Animal Model and Surgical Procedures

2.9. Echocardiographic Examination

2.10. Measurement of Serum NT-proBNP and cTnT

2.11. Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) Staining

2.12. Masson Staining

2.13. Detection of Apoptosis in Tissue Sections

2.14. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.15. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.16. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay

2.17. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release Assay

2.18. Flow Cytometry

2.19. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.20. ER-Tracker Red Staining

2.21. Western Blot (WB)

2.22. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

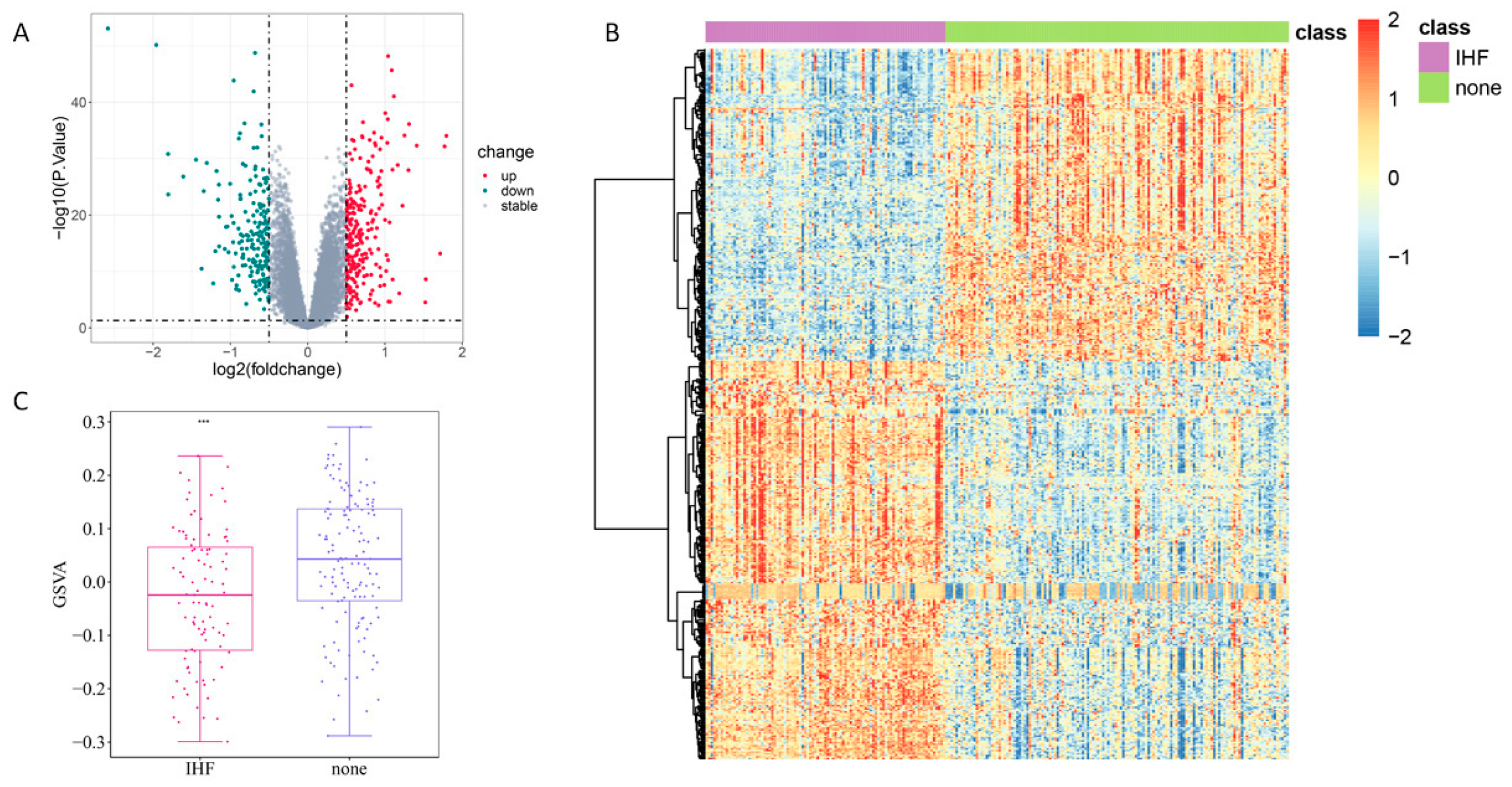

3.1. DEA of IHF-Related Genes and Analysis of ERS-Related Genes

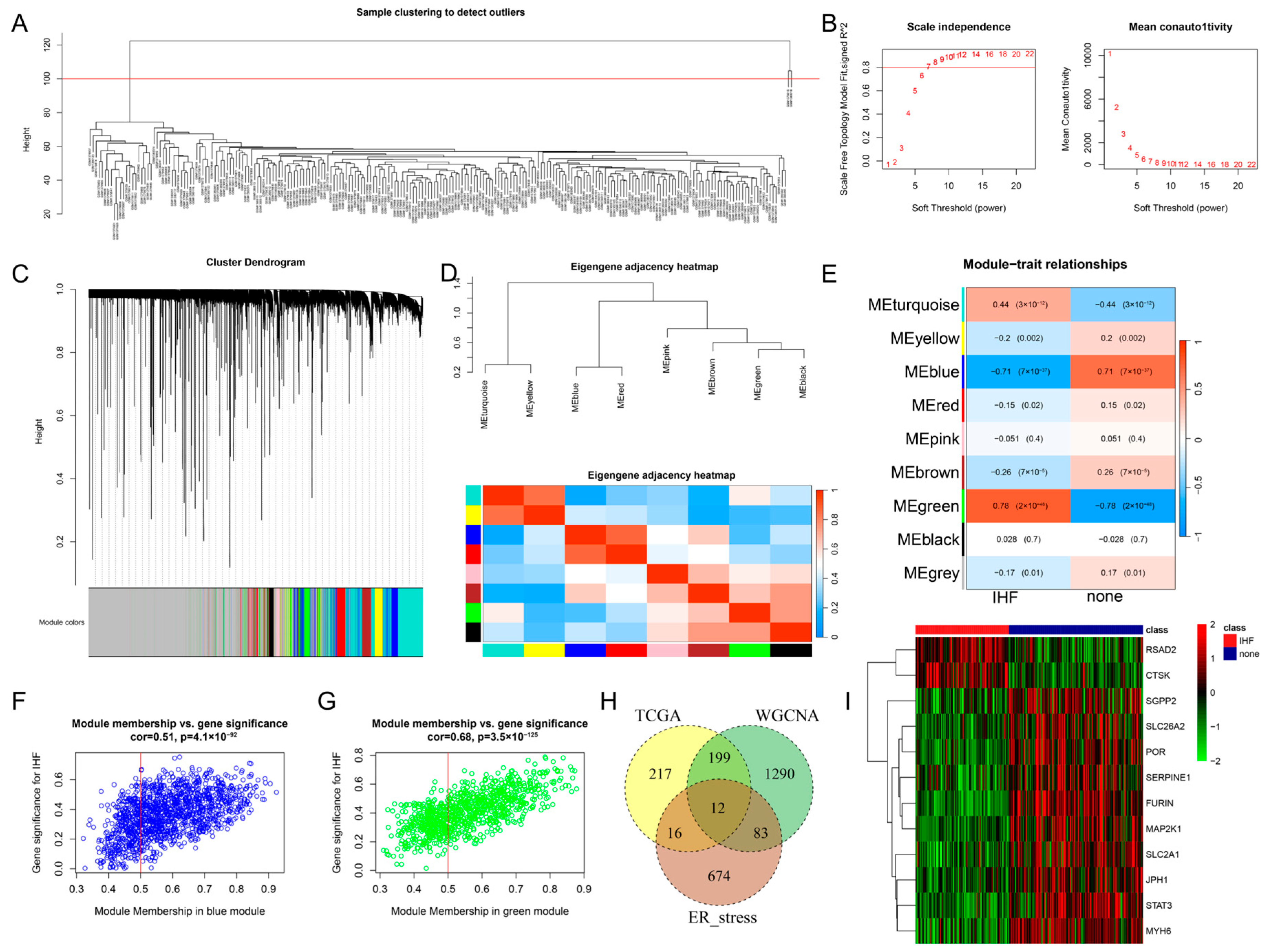

3.2. WGCNA

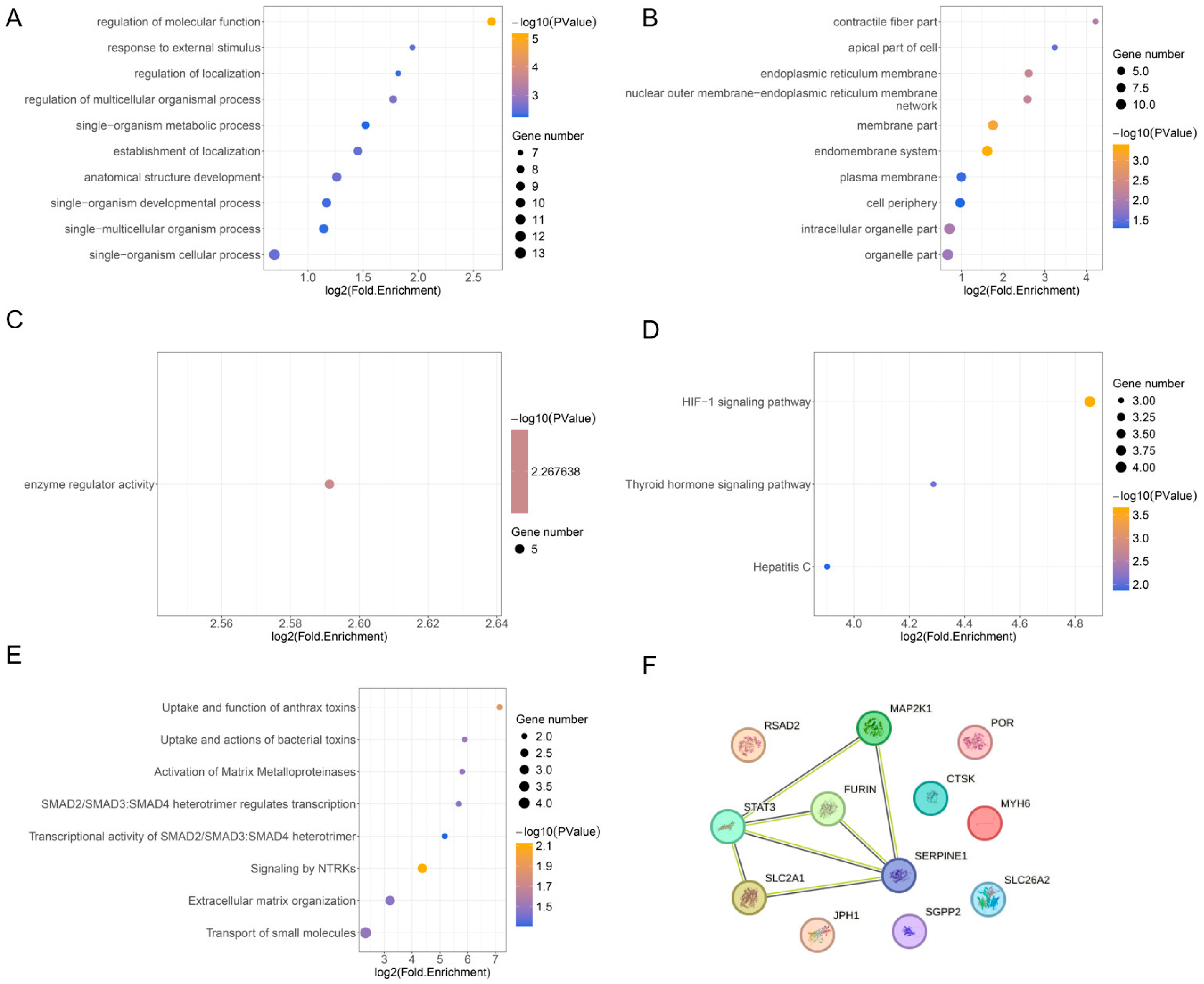

3.3. FEA and PPI Analysis

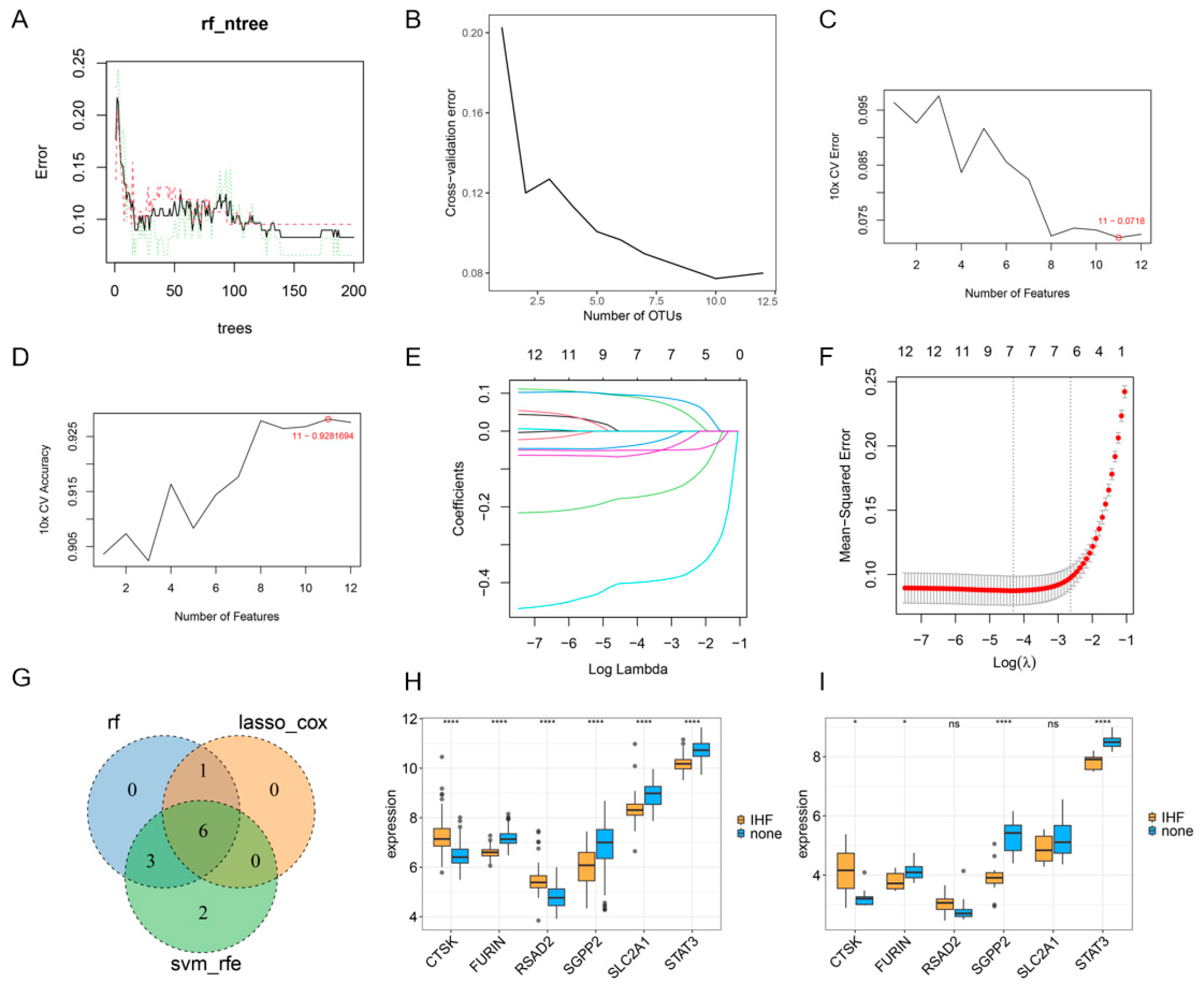

3.4. ML Analysis of Core Genes

3.5. The Results of Single-Cell Analysis

3.6. The Results of Immune Infiltration Analysis

3.7. SGEA

3.8. SGPP2 Is Downregulated in Rats with IHF

3.9. SGPP2 Alleviates OGD-Triggered Cardiomyocyte Injury

3.10. SGPP2 Alleviates OGD-Triggered Cardiomyocyte Injury by Modulating ERS

3.11. SGPP2 Alleviates OGD-Induced Cardiomyocyte ERS via the SIRT1/AMPK Signaling Pathway

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SGPP2 | sphingosine-1-phosphatase 2 |

| ERS | endoplasmic reticulum stress |

| SIRT1 | sirtuin 1 |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| HF | heart failure |

| ICM | ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| IHF | ischemic cardiomyopathy-induced chronic heart failure |

| NRCMs | neonatal rat cardiomyocytes |

| OGD | oxygen-glucose deprivation |

| Tu | tunicamycin |

| UPR | unfolded protein response |

| PERK | protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| ATF | activating transcription factor |

| CHOP | C/EBP-homologous protein |

| S1P | sphingosine-1-phosphate |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| GSVA | gene set variation analysis |

| WGCNA | weighted gene co-expression network analysis |

| PPI | protein–protein interaction |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| BP | biological process |

| CC | cellular component |

| MF | molecular function |

| SGEA | single-gene enrichment analysis |

| SD | Sprague–Dawley |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVEDD | left ventricular end-diastolic diameter |

| LVEDS | left ventricular end-systolic diameter |

| LVFS | left ventricular fractional shortening |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal Pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| OD | optical density |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| oe-SGPP2 | SGPP2 overexpression plasmid |

| oe-NC | negative control plasmid |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| WB | Western Blot |

References

- Khan, M.S.; Shahid, I.; Bennis, A.; Rakisheva, A.; Metra, M.; Butler, J. Global epidemiology of heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhai, L.; Yang, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, T.; Chen, A.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Li, C.; et al. Integrative Proteomic Analysis Reveals the Cytoskeleton Regulation and Mitophagy Difference Between Ischemic Cardiomyopathy and Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2023, 22, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Bi, Y.; Sowers, J.R.; Hetz, C.; Zhang, Y. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 499–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Geng, J.; Chen, F.; Wei, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Gao, L.; et al. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 knockdown attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis by targeting p53 following myocardial infarction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 8369–8380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, S.A.; Papa, F.R. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human pathology. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2015, 10, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shi, C.; He, M.; Xiong, S.; Xia, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyani, C.N.; Plastira, I.; Sourij, H.; Hallstrom, S.; Schmidt, A.; Rainer, P.P.; Bugger, H.; Frank, S.; Malle, E.; von Lewinski, D. Empagliflozin protects heart from inflammation and energy depletion via AMPK activation. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 158, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Li, J.; Zhou, L. Ginsenoside Rg1 regulates autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress via the AMPK/mTOR and PERK/ATF4/CHOP pathways to alleviate alcohol-induced myocardial injury. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2023, 52, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Song, X. Quercetin attenuates sepsis-induced acute lung injury via suppressing oxidative stress-mediated ER stress through activation of SIRT1/AMPK pathways. Cell. Signal. 2022, 96, 110363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaoa, R.M.; Al-Rabia, M.W.; Asfour, H.Z.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Mansouri, R.A.; El-Agamy, D.S.; Abdulaal, W.H.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Elshal, M. Targeting SIRT1/AMPK/Nrf2/NF-small ka, CyrillicB by sitagliptin protects against oxidative stress-mediated ER stress and inflammation during ANIT-induced cholestatic liver injury. Toxicology 2024, 507, 153889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Liu, L.; Zou, R.; Zou, M.; Zhang, M.; Cao, F.; Liu, W.; Yuan, H.; Huang, G.; Ma, L.; et al. Circular Network of Coregulated Sphingolipids Dictates Chronic Hypoxia Damage in Patients with Tetralogy of Fallot. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 780123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, Y.; Allende, M.L.; Mizukami, H.; Cook, E.K.; Gavrilova, O.; Tuymetova, G.; Clarke, B.A.; Chen, W.; Olivera, A.; Proia, R.L. Sphingosine-1-phosphate Phosphatase 2 Regulates Pancreatic Islet beta-Cell Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 12029–12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, T.; Chen, M.; Sun, F.; Fei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tian, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, W.; et al. Morroniside induces cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity and promotes cardiac repair after myocardial infarction in adult rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1260674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, R.; Shen, H.; Mo, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Li, S.; Liang, G.; Hou, N.; Luo, J. Endophilin A2-mediated alleviation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cardiac injury involves the suppression of ERO1alpha/IP(3)R signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 3672–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H. AMPK Signalling Pathway: A Potential Strategy for the Treatment of Heart Failure with Chinese Medicine. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 5451–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xu, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Bai, M.; Lou, Y.; Yang, Q. SIRT1 regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress-related organ damage. Acta Histochem. 2024, 126, 152134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Qian, H.; Tian, D.; Yang, M.; Li, D.; Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Hao, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Linggui Zhugan Decoction activates the SIRT1-AMPK-PGC1alpha signaling pathway to improve mitochondrial and oxidative damage in rats with chronic heart failure caused by myocardial infarction. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1074837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Binder, P.; Fang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart: Insights into mechanisms and drug targets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1293–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Gao, D.; Lv, H.; Lian, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, J. Finding New Targets for the Treatment of Heart Failure: Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Autophagy. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2023, 16, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabirli, R.; Koseler, A.; Mansur, N.; Zeytunluoglu, A.; Sabirli, G.T.; Turkcuer, I.; Kilic, I.D. Predictive Value of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Markers in Low Ejection Fractional Heart Failure. Vivo 2019, 33, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momot, K.; Wojciechowska, M.; Krauz, K.; Czarzasta, K.; Puchalska, L.; Zarebinski, M.; Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska, A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and expression of nitric oxide synthases in heart failure with preserved and with reduced ejection fraction—Pilot study. Cardiol. J. 2024, 31, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Xu, W.; Shang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Jin, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Apelin ameliorated acute heart failure via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress in rabbits. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, J.; Huang, Y. Identification of hub genes in heart failure by integrated bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1332287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, C. SGPP2 is activated by SP1 and promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression. Anticancer Drugs 2024, 35, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldovan, A.; Wagner, F.; Schumacher, F.; Wigger, D.; Kessie, D.K.; Ruhling, M.; Stelzner, K.; Tschertok, R.; Kersting, L.; Fink, J.; et al. Chlamydia trachomatis exploits sphingolipid metabolic pathways during infection of phagocytes. Mbio 2025, 16, e0398124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackland, J.; Barber, C.; Heinson, A.; Azim, A.; Cleary, D.W.; Christodoulides, M.; Kurukulaaratchy, R.J.; Howarth, P.; Wilkinson, T.M.A.; Staples, K.J.; et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae infection of pulmonary macrophages drives neutrophilic inflammation in severe asthma. Allergy 2022, 77, 2961–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannuzzi, V.; Bernacchioni, C.; Muccilli, A.; Castiglione, F.; Nozzoli, F.; Vannuccini, S.; Capezzuoli, T.; Ceccaroni, M.; Bruni, P.; Donati, C.; et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate pathway is dysregulated in adenomyosis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2022, 45, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Mu, N.; Yin, Y.; Yu, L.; Ma, H. Targeting AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Aging-Related Cardiovascular Diseases. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; You, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Pan, Z.; Li, D.; Ling, W. beta-Hydroxybutyrate Alleviates Atherosclerotic Calcification by Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis via AMPK/Nrf2 Pathway. Nutrients 2024, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, N.; Servillo, L.; Balestrieri, M.L. SIRT1 and SIRT6 Signaling Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease Protection. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 711–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhao, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, N.; Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; Lian, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Sirt1 improves heart failure through modulating the NF-kappaB p65/microRNA-155/BNDF signaling cascade. Aging 2020, 13, 14482–14498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Fu, L. SGPP2 Ameliorates Chronic Heart Failure by Attenuating ERS via the SIRT1/AMPK Pathway. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010100

Kang Y, Wang Y, Wang L, Fu L. SGPP2 Ameliorates Chronic Heart Failure by Attenuating ERS via the SIRT1/AMPK Pathway. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Yang, Yang Wang, Lili Wang, and Lu Fu. 2026. "SGPP2 Ameliorates Chronic Heart Failure by Attenuating ERS via the SIRT1/AMPK Pathway" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010100

APA StyleKang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, L., & Fu, L. (2026). SGPP2 Ameliorates Chronic Heart Failure by Attenuating ERS via the SIRT1/AMPK Pathway. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010100