Genome-Wide Insights into Intermittent Milking Behavior of Pandharpuri Buffalo

Abstract

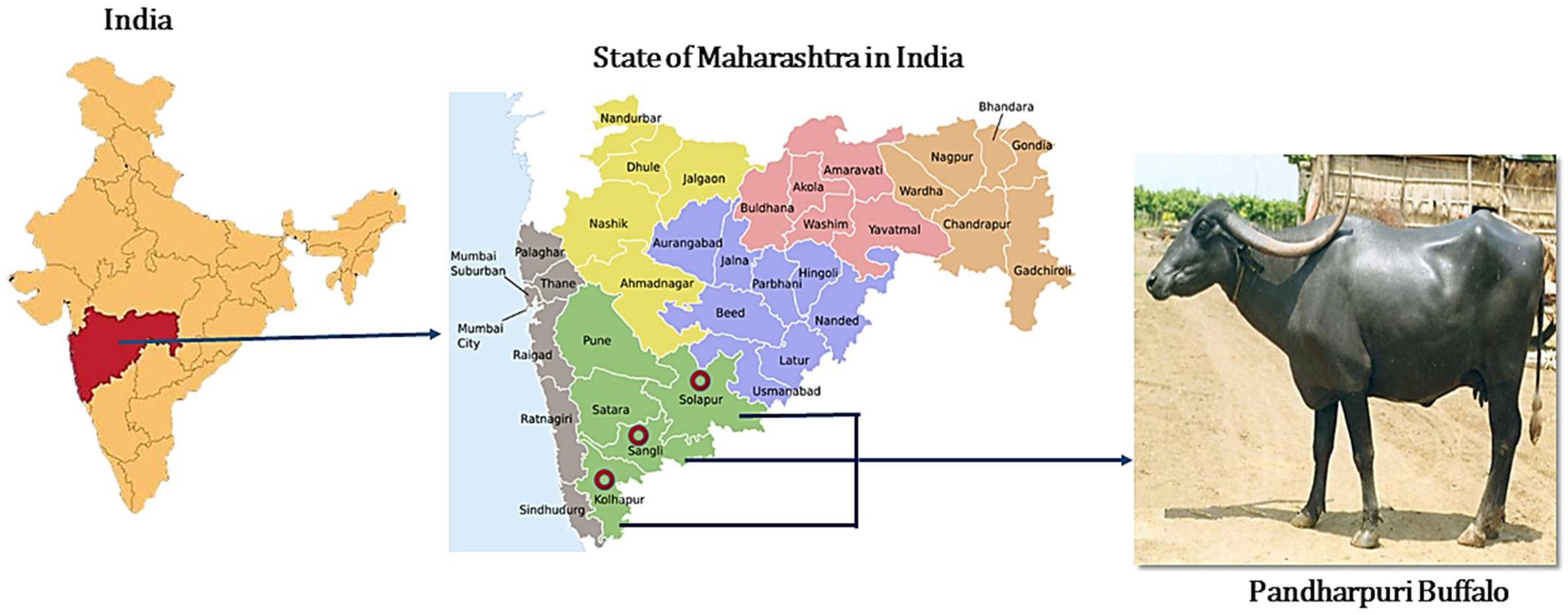

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Whole-Genome Resequencing and Variant Detection

2.2. High-Confidence Variant Selection and Phasing

2.3. Computation of Intra-Population Selection Statistics

2.4. Composite Selection Signature Analysis Using DCMS

2.5. Functional Annotation and Hub Gene Identification

3. Results

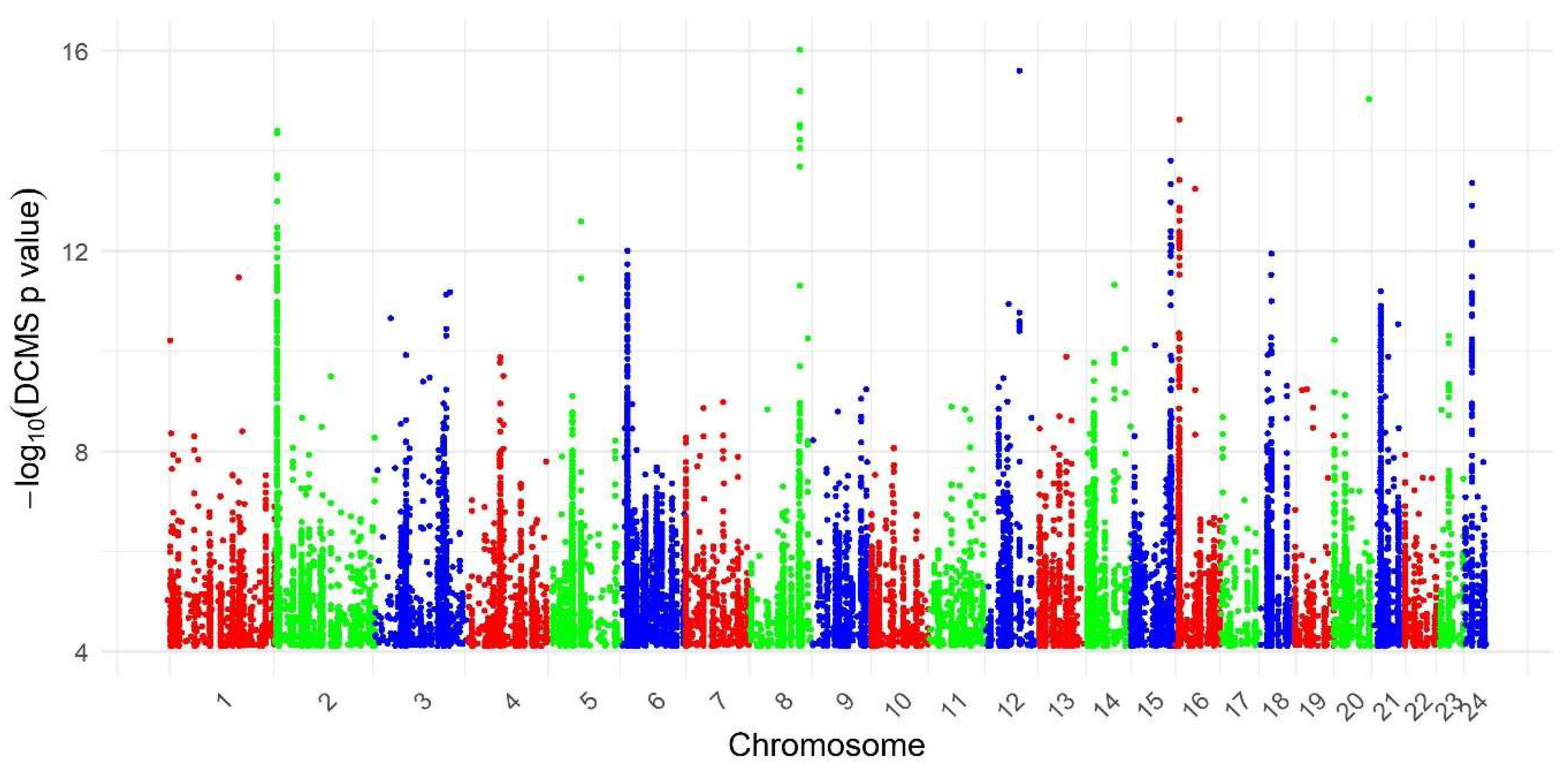

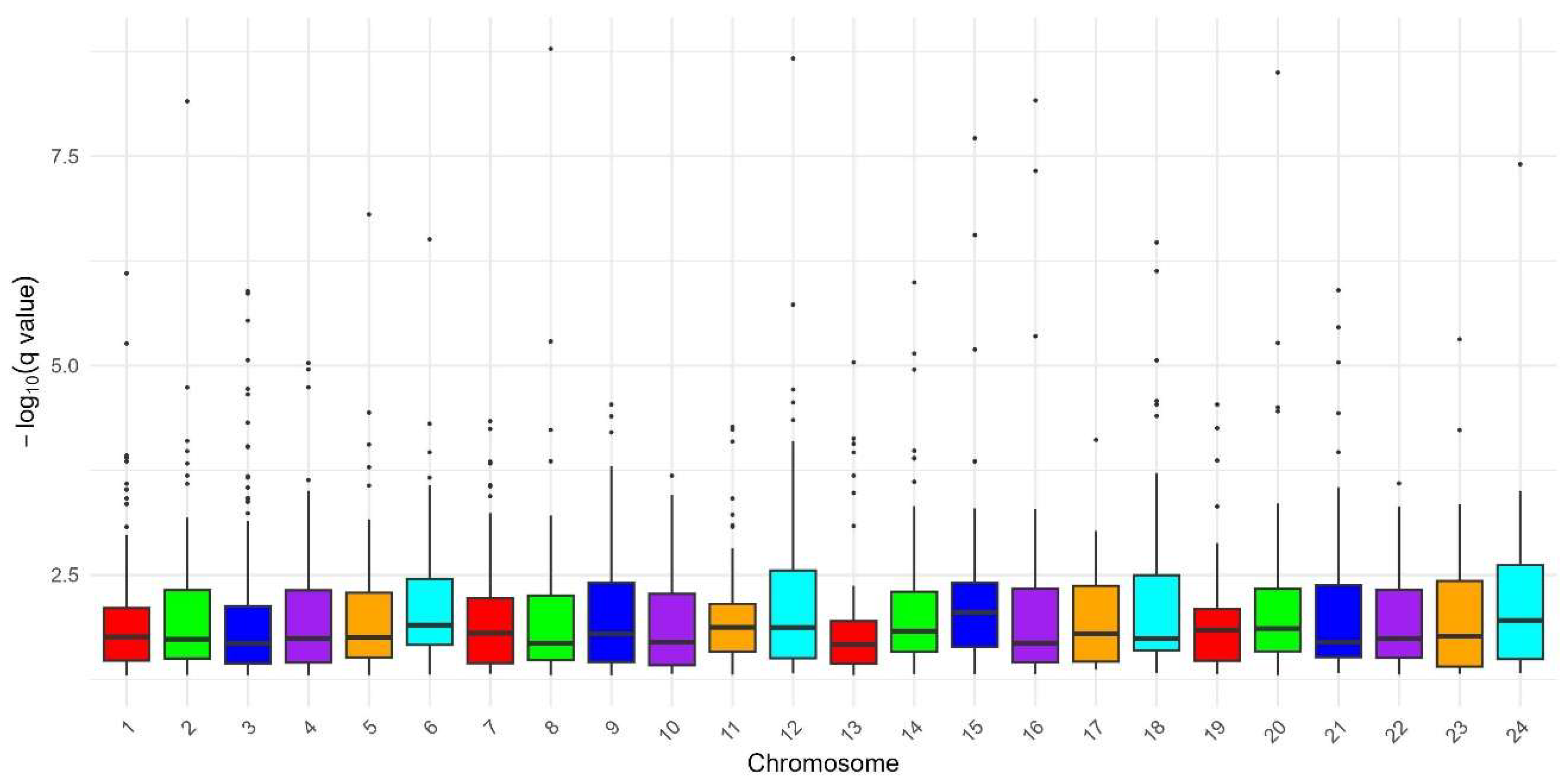

3.1. Genome-Wide Detection of Putative Selection Signatures Using DCMS

3.2. Biological Processes and Pathways Enriched Among Candidate Genes

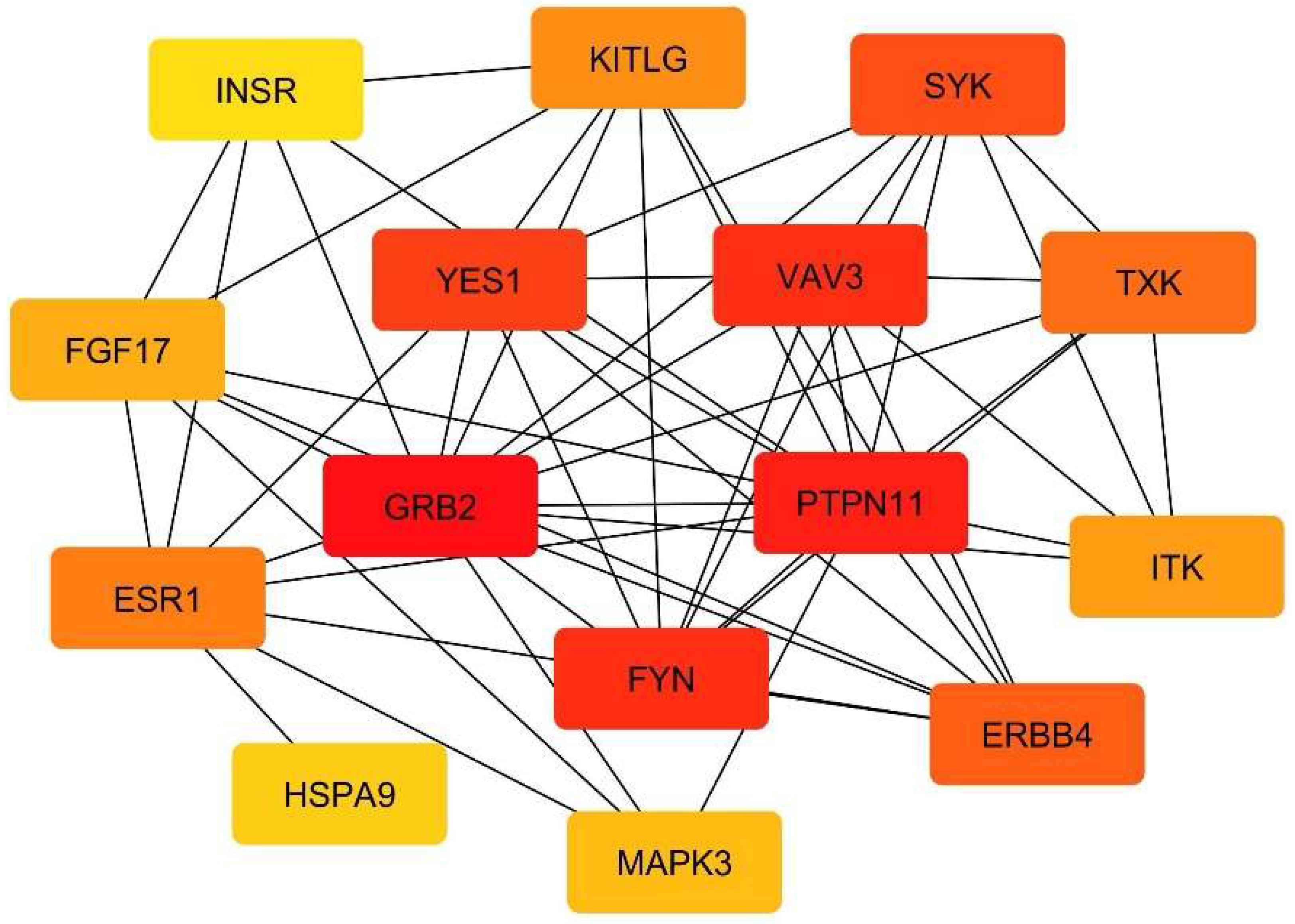

3.3. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis and Identification of Key Hub Genes

4. Discussion

Future Directions: Validation and Functional Implementation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lappalainen, T.; Scott, A.J.; Brandt, M.; Hall, I.M. Genomic analysis in the age of human genome sequencing. Cell 2019, 177, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Luan, P.; Xiao, F.; Gao, H.; Guo, H.; et al. A combination of genome-wide association study and selection signature analysis dissects the genetic architecture underlying bone traits in chickens. Animal 2021, 15, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yao, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Chen, N.; Xia, X.; Lyu, S.; Shi, Q.; et al. Assessing genomic diversity and signatures of selection in Pinan cattle using whole-genome sequencing data. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Xiong, J.; Huang, J.; Yang, P.; Shang, M.; Zhang, L. Genetic Diversity, Selection Signatures, and Genome-Wide Association Study Identify Candidate Genes Related to Litter Size in Hu Sheep. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Shi, W.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, G.; Cao, J.; et al. Selection signatures and landscape genomics analysis to reveal climate adaptation of goat breeds. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, S.V.; Alexandri, P.; van der Werf, J.H.; Olmo, L.; Walkden-Brown, S.W.; de Las Heras-Saldana, S. Signature of Selection Analysis Reveals Candidate Genes Related to Climate Adaptation and Production Traits in Lao Native Goats. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2025, 142, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M.; Haigh, J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet. Res. 1974, 23, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitman, M. Methods to detect selection in populations with applications to the human. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2000, 1, 539–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R. Statistical tests of selective neutrality in the age of genomics. Heredity 2001, 86, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.D.; Foll, M.; Bernatchez, L. The past, present and future of genomic scans for selection. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, A.A.; Daetwyler, H.D.; Yudin, N.; Schnabel, R.D.; Jagt, C.J.V.; Soloshenko, V.; Lhasaranov, B.; Popov, R.; Taylor, J.F.; Larkin, D.M. Scans for signatures of selection in Russian cattle breed genomes reveal new candidate genes for environmental adaptation and acclimation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Sartor, M.; Cavalcoli, J. Current status and future perspectives for sequencing livestock genomes. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarani, A.; Sorbolini, S.; Criscione, A.; Bordonaro, S.; Pulina, G.; Battacone, G.; Marletta, D.; Gaspa, G.; Macciotta, N.P.P. Genome-wide variability and selection signatures in Italian island cattle breeds. Anim. Genet. 2018, 49, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, M.; Charlier, C.; Hayes, B. Harnessing genomic information for livestock improvement. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illa, S.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Nath, S.; Mukherjee, A. Genome-wide scanning for signatures of selection revealed putative genomic regions and candidate genes controlling milk composition and coat color traits in Sahiwal cattle. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 699422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.P.; Khan, K.D.; Yadav, A.; Gahlyan, R.K.; Vohra, V.; Alex, R.; Gowane, G.R. Exploring genomic signatures of selection for adaptation and resilience in nomadic Belahi cattle in the tropical climate. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhu, Q.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C. Potential genetic markers associated with environmental adaptability in herbivorous livestock. Animals 2025, 15, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaglan, K.; Sukhija, N.; KK, K.; Verma, A.; Vohra, V.; Alex, R.; George, L. Surveying selection signatures in Murrah buffalo using genome-wide SNP data. Cytol. Genet. 2025, 59, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 1989, 123, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, M.; Li, W.H. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 5269–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, J.C.; Wu, C.I. Hitchhiking under positive Darwinian selection. Genetics 2000, 155, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Stephan, W. Detecting a local signature of genetic hitchhiking along a recombining chromosome. Genetics 2002, 160, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voight, B.F.; Kudaravalli, S.; Wen, X.; Pritchard, J.K. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e72, Correction in PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e154. Correction in PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e147.. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Admetlla, A.; Liang, M.; Korneliussen, T.; Nielsen, R. On detecting incomplete soft or hard selective sweeps using haplotype structure. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 1275–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotterhos, K.E.; Whitlock, M.C. The relative power of genome scans to detect local adaptation depends on sampling design and statistical method. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 1031–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ding, X.; Qanbari, S.; Weigend, S.; Zhang, Q.; Simianer, H. Properties of different selection signature statistics and a new strategy for combining them. Heredity 2015, 115, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, A.A.; Deniskova, T.E.; Yudin, N.S.; Dotsev, A.V.; Khamiruev, T.N.; Selionova, M.I.; Egorov, S.V.; Reyer, H.; Wimmers, K.; Brem, G.; et al. High-density genotyping reveals signatures of selection related to acclimation and economically important traits in 15 local sheep breeds from Russia. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreishifar, S.M.; Eriksson, S.; Johansson, A.M.; Khansefid, M.; Moghaddaszadeh-Ahrabi, S.; Parna, N.; Davoudi, P.; Javanmard, A. Signatures of selection reveal candidate genes involved in economic traits and cold acclimation in five Swedish cattle breeds. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2020, 52, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweet-Jones, J.; Lenis, V.P.; Yurchenko, A.A.; Yudin, N.S.; Swain, M.; Larkin, D.M. Genotyping and whole-genome resequencing of Welsh sheep breeds reveal candidate genes and variants for adaptation to local environment and socioeconomic traits. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 612492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Abri, M.; Alfoudari, A.; Mohammad, Z.; Almathen, F.; Al-Marzooqi, W.; Al-Hajri, S.; Al-Amri, M.; Bahbahani, H. Assessing genetic diversity and defining signatures of positive selection on the genome of dromedary camels from the southeast of the Arabian Peninsula. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1296610. [Google Scholar]

- Muansangi, L.; Tiwari, J.; Ilayaraja, I.; Kumar, I.; Vyas, J.; Chitra, A.; Singh, S.P.; Pal, P.; Gowane, G.; Mishra, A.K.; et al. DCMS analysis revealed differential selection signatures in the transboundary Sahiwal cattle for major economic traits. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, M.; Akinsola, O.M.; Pal, P.; Ramasamy, C.; Ramasamy, S.; Musa, A.A.; Thiruvenkadan, A.K. Comparative genomic insights into adaptation, selection signatures, and population dynamics in indigenous Indian sheep and foreign breeds. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1621960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsunomiya, Y.T.; Pérez O’Brien, A.M.; Sonstegard, T.S.; Sölkner, J.; Garcia, J.F. Genomic data as the “hitchhiker’s guide” to cattle adaptation: Tracking the milestones of past selection in the bovine genome. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.K.; Mohanty, T.K.; Kumaresan, A.; Bhakat, M.; Sathapathy, S. Changes in Teat Morphology (Doka Phenomenon) and Estrus Prediction in Riverine Buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis). Indian J. Anim. Res. 2020, 54, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizelj, J.; Katana, B.; Dobranic, T.; Prvanovic, N.; Lipar, M.; Vince, S.; Stanin, D.; Djuricic, D.; Greguric-Gracner, G.; Samardzija, M. The efficacy of milk ejection induced by luteal oxytocin as a method of early pregnancy diagnostics in cows. Acta Vet. 2010, 60, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kumar, S.; Nagarajan, M.; Sandhu, J.S.; Kumar, N.; Behl, V. Phylogeography and domestication of Indian river buffalo. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Talenti, A.; Young, R.; Jayaraman, S.; Callaby, R.; Jadhav, S.K.; Dhanikachalam, V.; Manikandan, M.; Biswa, B.B.; Low, W.Y.; et al. Whole genome analysis of water buffalo and global cattle breeds highlights convergent signatures of domestication. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol: Chloroform. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2006, 2006, pdb.prot4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaneau, O.; Marchini, J.; Zagury, J.F. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpiech, Z.A.; Hernandez, R.D. selscan: An efficient multithreaded program to perform EHH-based scans for positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 31, 2824–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein–protein association networks with increased coverage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.H.; Chen, S.H.; Wu, H.H.; Ho, C.W.; Ko, M.T.; Lin, C.Y. cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Pardo, A.P.; Ruzzante, D.E. Whole-genome sequencing approaches for conservation biology: Advantages, limitations and practical recommendations. Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 5369–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhosh, A.; Vohra, V.; Alex, R.; Gowane, G. Genome-wide SNP identification and annotation from high-coverage whole-genome sequenced data of Bhadawari buffalo. Indian J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 77, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraoka-Cook, R.S.; Feng, S.M.; Strunk, K.E.; Earp, H.S. ErbB4/HER4: Role in mammary gland development, differentiation and growth inhibition. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2008, 13, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morato, A.; Accornero, P.; Hovey, R.C. ERBB receptors and their ligands in the developing mammary glands of different species. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2023, 28, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, V.B.; Gilmore-Hebert, M.; Mamillapalli, R.; Haskins, J.W.; Kurppa, K.J.; Elenius, K.; Booth, C.J.; Stern, D.F. Overexpression of ERBB4 JM-a CYT-1 and CYT-2 isoforms in transgenic mice reveals isoform-specific roles in mammary gland development and carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraoka-Cook, R.S.; Sandahl, M.A.; Strunk, K.E.; Miraglia, L.C.; Husted, C.; Hunter, D.M.; Elenius, K.; Chodosh, L.A.; Earp, H.S. ErbB4 splice variants Cyt1 and Cyt2 differ by 16 amino acids and exert opposing effects on the mammary epithelium in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 4935–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, R.; Chao, T.; Zhao, X.; Wang, A.; Chu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, Z.; Wang, J. Transcriptome profiling of the nonlactating mammary glands of dairy goats reveals the molecular genetic mechanism of mammary cell remodeling. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 5238–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.K.; Choudhary, S.; Mukhopadhyay, C.S.; Pathak, D.; Verma, R. Deciphering the transcriptome of prepubertal buffalo mammary glands using RNA sequencing. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2019, 19, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, H.L.M.; Parsons, C.L.M.; Ellis, S.; Rhoads, M.L.; Akers, R.M. Tamoxifen impairs prepubertal mammary development and alters expression of estrogen receptor α (ESR1) and progesterone receptors (PGR). Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2016, 54, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colitti, M.; Pulina, G. Expression profile of caseins, estrogen and prolactin receptors in mammary glands of dairy ewes. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 9, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessauge, F.; Finot, L.; Wiart, S.; Aubry, J.M.; Ellis, S.E. Effects of ovariectomy in prepubertal goats. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009, 60, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Lin, L.; Xing, W.; Yang, Y.; Duan, X.; Li, Q.; Gao, X.; Lin, Y. Spleen tyrosine kinase regulates mammary epithelial cell proliferation in mammary glands of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 3858–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chen, F.; Li, L.; Yan, L.; Badri, T.; Lv, C.; Yu, D.; Zhang, M.; Jang, X.; Li, J.; et al. Three novel players: PTK2B, SYK, and TNFRSF21 involved in regulation of bovine mastitis susceptibility via GWAS and post-transcriptional analysis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yuan, L.; Xiang, M.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Chen, F.; Tong, J.; Huang, J.; Cai, Y. A novel TLR4–SYK interaction axis plays an essential role in innate immunity response in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Biomedicines 2022, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchyta, S.P.; Sipkovsky, S.; Halgren, R.G.; Kruska, R.; Elftman, M.; Weber-Nielsen, M.; Vandehaar, M.J.; Xiao, L.; Tempelman, R.J.; Coussens, P.M. Bovine mammary gene expression profiling using a cDNA microarray enriched for mammary-specific transcripts. Physiol. Genom. 2003, 16, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.S.; Panigrahi, M.; Rajawat, D.; Ghildiyal, K.; Sharma, A.; Parida, S.; Bhushan, B.; Mishra, B.P.; Dutt, T. Comprehensive selection signature analyses in dairy cattle exploiting purebred and crossbred genomic data. Mamm. Genome 2023, 34, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhotaray, S.; Vohra, V.; Uttam, V.; Santhosh, A.; Saxena, P.; Gahlyan, R.K.; Gowane, G. TWAS revealed significant causal loci for milk production and composition in Murrah buffaloes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, N.; Vishwakarma, S.; Katara, P. Identification and annotation of milk-associated genes from milk somatic cells using expression and RNA-seq data. Bioinformation 2022, 18, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Li, P.; Hao, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, B. Enhancing milk production by nutrient supplements: Strategies and regulatory pathways. Animals 2023, 13, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Lv, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Han, B.; Sun, D. A post-GWAS confirming effects of PRKG1 gene on milk fatty acids in a Chinese Holstein dairy population. BMC Genet. 2019, 20, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyazbekova, Z.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, M.; Wang, H.P.; Primkul, I.; Nanaei, H.A.; Ussenbekov, Y.; Kassen, K.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C.Y.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals genetic architecture and selection signatures of Kazakh cattle. Zool. Res. 2025, 46, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.No | Chromosome | Start Position (bp) | End Position (bp) | Window Length (bp) | Number of SNPs | Minimum q-Value | Position of Top SNP (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 93,753,221 | 93,949,273 | 196,053 | 179 | 1.66 × 10−9 | 93,799,967 |

| 2 | 12 | 66,038,739 | 66,099,934 | 61,196 | 38 | 2.16 × 10−9 | 66,099,317 |

| 3 | 20 | 64,396,901 | 64,449,434 | 52,534 | 36 | 3.16 × 10−9 | 64,439,325 |

| 4 | 16 | 8,725,242 | 8,990,446 | 265,205 | 204 | 6.83 × 10−9 | 8,810,042 |

| 5 | 2 | 4,741,928 | 4,799,861 | 57,934 | 317 | 6.98 × 10−9 | 4,778,662 |

| 6 | 15 | 73,748,472 | 73,877,721 | 129,250 | 446 | 1.93 × 10−8 | 73,843,490 |

| 7 | 24 | 16,000,435 | 16,104,795 | 104,361 | 153 | 3.94 × 10−8 | 16,082,640 |

| 8 | 16 | 37,625,337 | 37,699,798 | 74,462 | 240 | 4.73 × 10−8 | 37,668,255 |

| 9 | 5 | 57,900,501 | 58,048,083 | 147,583 | 149 | 1.56 × 10−7 | 58,043,435 |

| 10 | 15 | 75,550,025 | 75,595,163 | 45,139 | 53 | 2.76 × 10−7 | 75,593,925 |

| 11 | 6 | 12,778,650 | 13,081,208 | 302,559 | 691 | 3.10 × 10−7 | 12,794,066 |

| 12 | 18 | 22,052,257 | 22,131,818 | 79,562 | 195 | 3.38 × 10−7 | 22,052,587 |

| 13 | 18 | 21,198,352 | 21,499,708 | 301,357 | 284 | 7.43 × 10−7 | 21,394,367 |

| 14 | 1 | 1.34 × 108 | 1.34 × 108 | 160,568 | 76 | 7.92 × 10−7 | 1.34 × 108 |

| 15 | 14 | 50,219,895 | 50,260,964 | 41,070 | 63 | 1.02 × 10−6 | 50,242,895 |

| 16 | 21 | 16,769,420 | 16,996,452 | 227,033 | 368 | 1.26 × 10−6 | 16,911,161 |

| 17 | 3 | 1.38 × 108 | 1.38 × 108 | 6834 | 4 | 1.29 × 10−6 | 1.38 × 108 |

| 18 | 3 | 1.31 × 108 | 1.31 × 108 | 194,299 | 286 | 1.38 × 10−6 | 1.31 × 108 |

| 19 | 12 | 46,304,985 | 46,343,138 | 38,154 | 4 | 1.87 × 10−6 | 46,304,985 |

| 20 | 3 | 29,153,265 | 29,158,280 | 5016 | 6 | 2.91 × 10−6 | 29,158,239 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Patil, A.; Gaur, P.; Pal, P.; Alex, R.; Chhotaray, S.; Gandham, R.K.; Vohra, V. Genome-Wide Insights into Intermittent Milking Behavior of Pandharpuri Buffalo. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010101

Patil A, Gaur P, Pal P, Alex R, Chhotaray S, Gandham RK, Vohra V. Genome-Wide Insights into Intermittent Milking Behavior of Pandharpuri Buffalo. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010101

Chicago/Turabian StylePatil, Akshata, Parth Gaur, Pritam Pal, Rani Alex, Supriya Chhotaray, Ravi Kumar Gandham, and Vikas Vohra. 2026. "Genome-Wide Insights into Intermittent Milking Behavior of Pandharpuri Buffalo" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010101

APA StylePatil, A., Gaur, P., Pal, P., Alex, R., Chhotaray, S., Gandham, R. K., & Vohra, V. (2026). Genome-Wide Insights into Intermittent Milking Behavior of Pandharpuri Buffalo. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010101