The Hippo Pathway in Metaplastic Breast Carcinoma: Prognostic Significance and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol and Included Patients

2.2. Study Variables

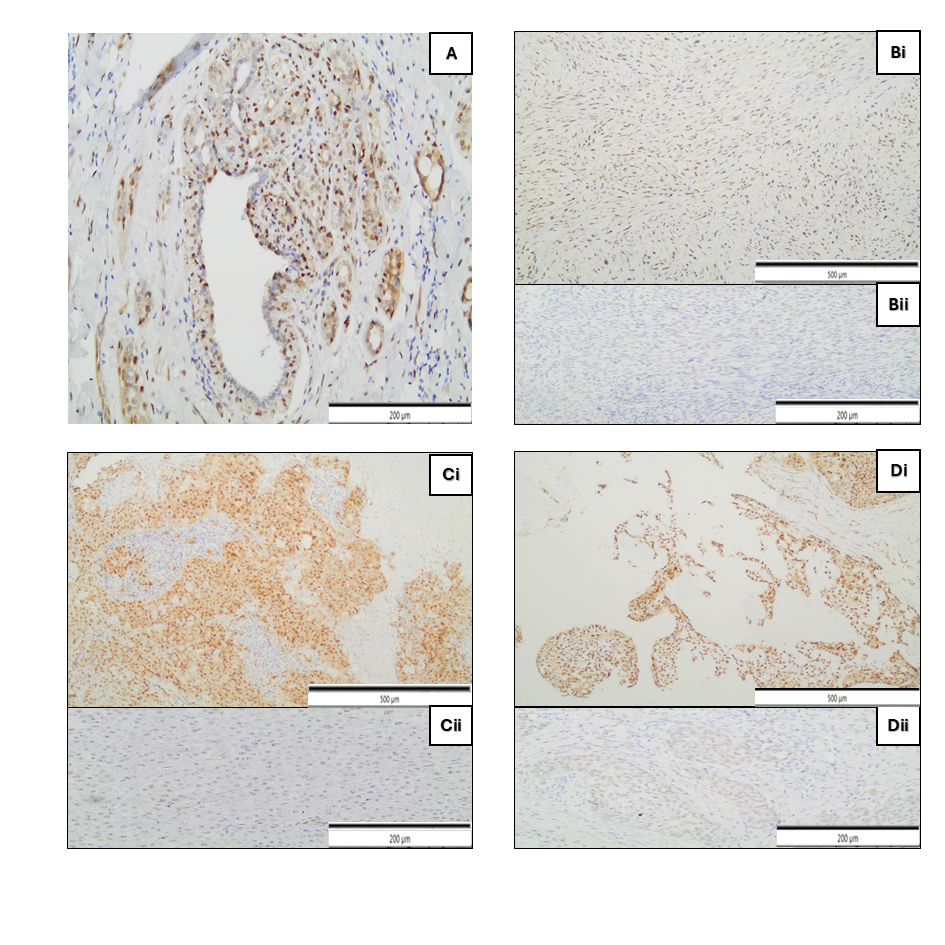

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

2.4. qRT-PCR

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Histology

3.3. Treatment Approach

3.4. YAP, TAZ, CCND1, CTGF Gene Expression

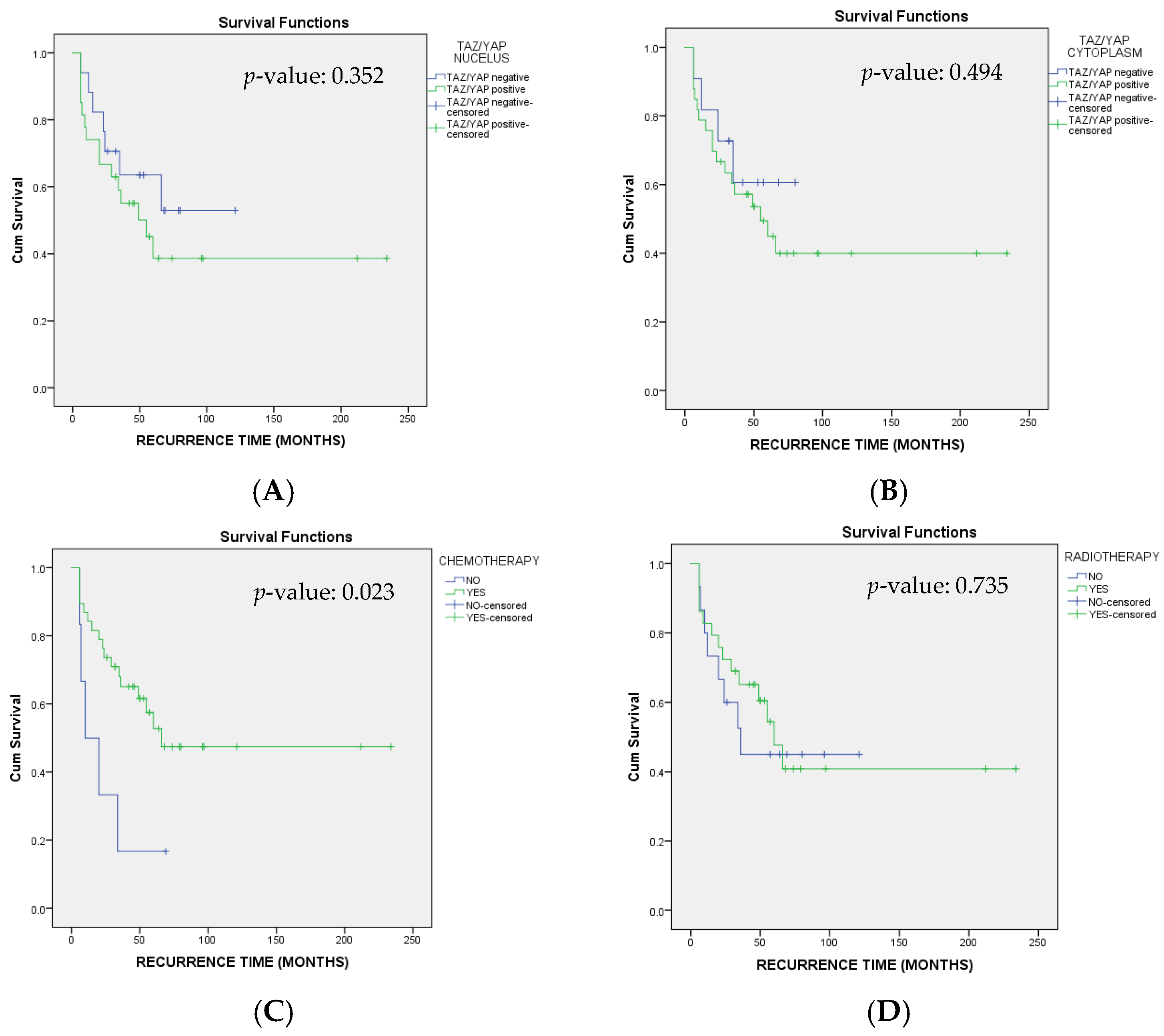

3.5. Disease-Free Survival (DFS)

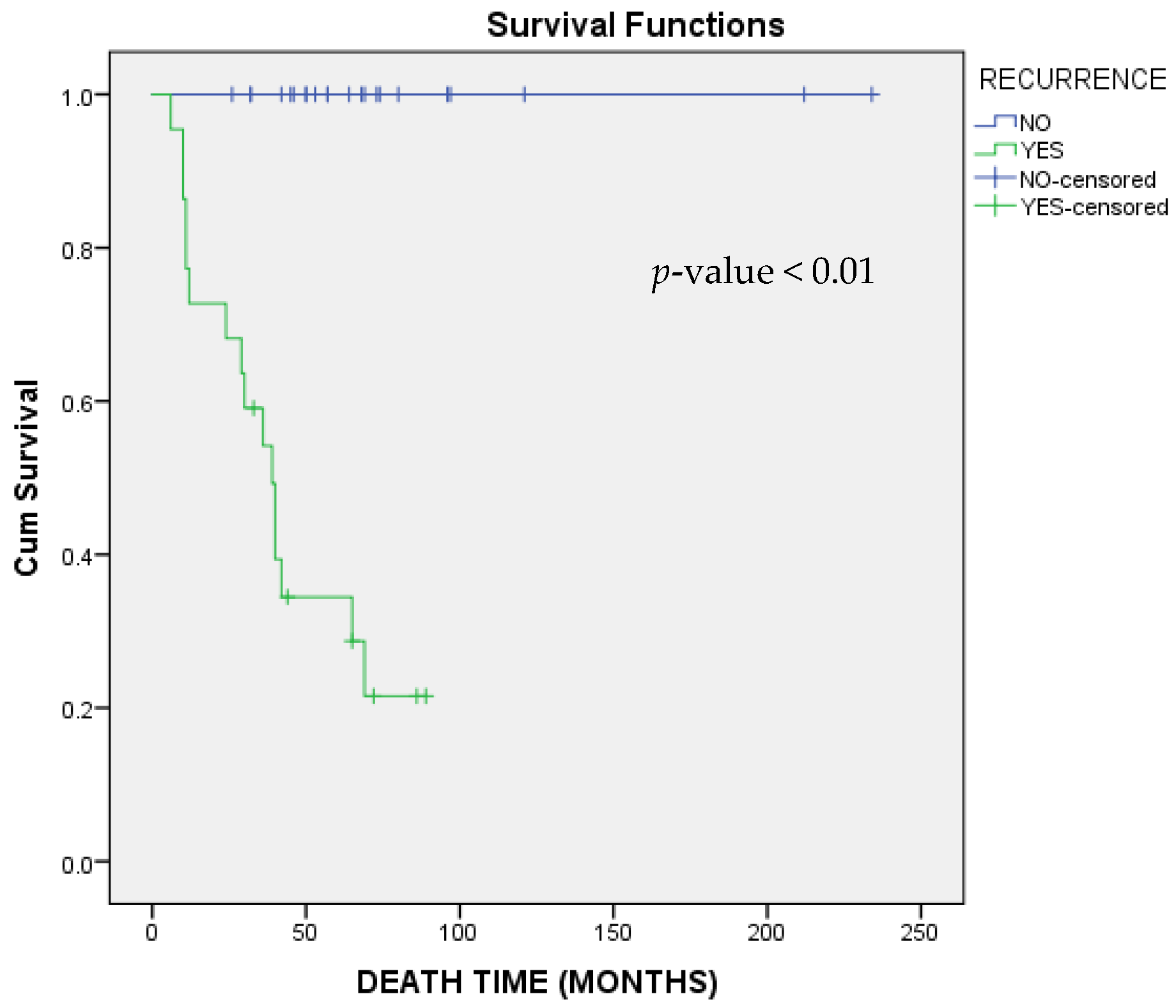

3.6. Overall Survival (OS)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsura, C.; Ogunmwonyi, I.; Kankam, H.K.; Saha, S. Breast cancer: Presentation, investigation and management. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 83, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, G.; Song, H.; Ren, Y.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; et al. Unique clinicopathological features of metaplastic breast carcinoma compared with invasive ductal carcinoma and poor prognostic indicators. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tray, N.; Taff, J.; Adams, S. Therapeutic landscape of metaplastic breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019, 79, 101888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinn, H.-P.; Kreipe, H. A brief overview of the WHO classification of breast tumors, focusing on issues and updates from the 3rd edition. Breast Care 2013, 8, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, E.R.; Zoumberos, N.A.; Kleer, C.G. Metaplastic breast carcinoma: Update on histopathology and molecular alterations. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2019, 143, 1492–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, J.S.; Miele, L. Breast cancer stem cells. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, R.W.; Zilian, O.; Woods, D.F.; Noll, M.; Bryant, P.J. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene warts encodes a homolog of human myotonic dystrophy kinase and is required for the control of cell shape and proliferation. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.S.; Park, H.W.; Guan, K.L. The Hippo signaling pathway in stem cell biology and cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri-Saccà, M.; De Maria, R. Hippo pathway and breast cancer stem cells. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 99, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazoglou, A.; Liontos, M.; Zakopoulou, R.; Kaparelou, M.; Tsiara, A.; Papatheodoridi, A.M.; Georgakopoulou, R.; Zagouri, F. The role of the Hippo pathway in breast cancer carcinogenesis, prognosis, and treatment: A systematic review. Breast Care 2021, 16, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Meng, Z.; Chen, R.; Guan, K.-L. The Hippo pathway: Biology and pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 577–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, M.D.; Krleza-Jeric, K.; Lemmens, T. The declaration of Helsinki. BMJ 2007, 335, 624–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elston, C.W.; Ellis, I.O. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: Experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology 1991, 19, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, A.E.; Edge, S.B.; Hortobagyi, G.N. of the AJCC cancer staging manual: Breast cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 1783–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrantia-Borunda, E.; Anchondo-Nuñez, P.; Acuña-Aguilar, L.E.; Gómez-Valles, F.O.; Ramírez-Valdespino, C.A. Subtypes of breast cancer. In Breast Cancer [Internet]; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Buglioni, S.; Vici, P.; Sergi, D.; Pizzuti, L.; Di Lauro, L.; Antoniani, B.; Sperati, F.; Terrenato, I.; Carosi, M.; Gamucci, T. Analysis of the hippo transducers TAZ and YAP in cervical cancer and its microenvironment. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1160187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieche, I.; Olivi, M.; Nogues, C.; Vidaud, M.; Lidereau, R. Prognostic value of CCND1 gene status in sporadic breast tumours, as determined by real-time quantitative PCR assays. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 86, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammarco, A.; Gomiero, C.; Sacchetto, R.; Beffagna, G.; Michieletto, S.; Orvieto, E.; Cavicchioli, L.; Gelain, M.E.; Ferro, S.; Patruno, M. Wnt/β-catenin and Hippo pathway deregulation in mammary tumors of humans, dogs, and cats. Vet. Pathol. 2020, 57, 774–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Twigg, S.; Chen, X.; Polhill, T.; Poronnik, P.; Gilbert, R.; Pollock, C. Integrated actions of transforming growth factor-β1 and connective tissue growth factor in renal fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2005, 288, F800–F809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zein, D.; Hughes, M.; Kumar, S.; Peng, X.; Oyasiji, T.; Jabbour, H.; Khoury, T. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast is more aggressive than triple-negative breast cancer: A study from a single institution and review of literature. Clin. Breast Cancer 2017, 17, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquet-Muñoz, S.A.; Villarreal-Colin, S.P.; Herrera-Montalvo, L.A.; Soto-Reyes, E.; Pérez-Plasencia, C.; Coronel-Martínez, J.; Pérez-Montiel, D.; Vázquez-Romo, R.; Cantú de León, D. Metaplastic breast cancer: A comparison between the most common histologies with poor immunohistochemistry factors. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, S.H.; Chen, C.L.; Huang, C.S.; Cheng, A.L. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast: Analysis of eight Asian patients with special emphasis on two unusual cases presenting with inflammatory-type breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2000, 20, 2219–2222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lah, N.A.S.N.; Imon, G.N.; Liew, J.E.; Jaafar, N.; Hayati, F.; Sharif, S.Z. Unique clinicopathological characteristic and survival rate of metaplastic breast cancer; a special subtype of breast cancer a 5 year cohort study in single referral centre in North Borneo. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 78, 103822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Jung, S.-Y.; Ro, J.Y.; Kwon, Y.; Sohn, J.H.; Park, I.H.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.W.; Kang, H.S. Metaplastic breast cancer: Clinicopathological features and its prognosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 65, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzi, C.M.; Patel-Parekh, L.; Cole, K.; Franko, J.; Klimberg, V.S.; Bland, K. Characteristics and treatment of metaplastic breast cancer: Analysis of 892 cases from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 14, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenfield, J.; Schammel, C.; Collins, J.; Schammel, D.; Edenfield, W.J. Metaplastic breast cancer: Molecular typing and identification of potential targeted therapies at a single institution. Clin. Breast Cancer 2017, 17, e1–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Ji, J.; Dong, R.; Liu, H.; Dai, X.; Wang, C.; Esteva, F.J.; Yeung, S.-C.J. Prognosis in different subtypes of metaplastic breast cancer: A population-based analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 173, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, T.P.; Rosato, R.R.; Li, X.; Moulder, S.; Piwnica-Worms, H.; Chang, J.C. A comprehensive overview of metaplastic breast cancer: Clinical features and molecular aberrations. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkenhol, M.C.; Vreuls, W.; Wauters, C.A.; Mol, S.J.; van der Laak, J.A.; Bult, P. Histological subtypes in triple negative breast cancer are associated with specific information on survival. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2020, 46, 151490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodoridi, A.; Papamattheou, E.; Marinopoulos, S.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Dimitrakakis, C.; Giannos, A.; Kaparelou, M.; Liontos, M.; Dimopoulos, M.-A.; Zagouri, F. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast: Case series of a single institute and review of the literature. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; He, X.; Chang, Y.; Sun, G.; Thabane, L. A sensitivity and specificity comparison of fine needle aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy in evaluation of suspicious breast lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast 2017, 31, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, T.; Lin, Q.; Wu, Z.; Cui, C.; Qi, C.; Li, L.; Su, X. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast: Imaging and pathological features. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 3975–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasdemir, O.A.; Tokgöz, S.; Köybaşıoğlu, F.; Karabacak, H.; Yücesoy, C.; İmamoğlu, G.İ. Clinicopathological features of metaplastic breast carcinoma. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 27, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieci, M.V.; Orvieto, E.; Dominici, M.; Conte, P.; Guarneri, V. Rare breast cancer subtypes: Histological, molecular, and clinical peculiarities. Oncologist 2014, 19, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, M.; Muneer, A.; Trivedi, V.; Mandal, K.; Shubham, S. Metaplastic carcinoma breast: A clinical analysis of nine cases. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2017, 11, XR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Dong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.; Ming, J.; Huang, T. Triple-negative metaplastic breast cancer: Treatment and prognosis by type of surgery. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 11689. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Glaberman, U.; Graham, A.; Stopeck, A. A case of metaplastic carcinoma of the breast responsive to chemotherapy with Ifosfamide and Etoposide: Improved antitumor response by targeting sarcomatous features. Breast J. 2010, 16, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, A.M.; Pettis, J.; Rivere, A.; Elder, E.A.; Fuhrman, G. Institutional Analysis of Metaplastic Breast Cancer. Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 3579–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Ming, J.; Huang, T. Metaplastic breast cancer: Treatment and prognosis by molecular subtype. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Feng, J.; Chen, C. Hippo pathway in mammary gland development and breast cancer. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2015, 47, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordenonsi, M.; Zanconato, F.; Azzolin, L.; Forcato, M.; Rosato, A.; Frasson, C.; Inui, M.; Montagner, M.; Parenti, A.R.; Poletti, A. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell 2011, 147, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Son, S.; Ko, Y.; Shin, I. CTGF regulates cell proliferation, migration, and glucose metabolism through activation of FAK signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40, 2667–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Morrison, C.D.; Liu, P.; Miecznikowski, J.; Bshara, W.; Han, S.; Zhu, Q.; Omilian, A.R.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. TAZ induces growth factor-independent proliferation through activation of EGFR ligand amphiregulin. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 2922–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Najm, M.Z.; Khan, M.A.; Akhter, N.; Shingatgeri, V.M.; Sikenis, M.; Sadaf; Aloliqi, A.A. Drug-resistant breast cancer: Dwelling the hippo pathway to manage the treatment. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2021, 13, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Martín, J.; López-García, M.; Romero-Pérez, L.; Atienza-Amores, M.R.; Pecero, M.L.; Castilla, M.; Biscuola, M.; Santón, A.; Palacios, J. Nuclear TAZ expression associates with the triple-negative phenotype in breast cancer. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2015, 22, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, T.; Puri, A.; Guzman-Rojas, L.; Thomas, C.; Qian, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, H.; Mahboubi, B.; Oo, A.; Cho, Y.J.; et al. NOS inhibition sensitizes metaplastic breast cancer to PI3K inhibition and taxane therapy via c-JUN repression. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yu, C.; Yang, W.; Jiang, N.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X. Recent Advances in Combination Therapy of YAP Inhibitors with Physical Anti-Cancer Strategies. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tang, T.; Zhou, T. Prognosis and clinicopathological characteristics of metaplastic breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e32226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Park, S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.-H.; Choi, S.-Y.; Park, B.-W.; Lee, K.-S. Clinicopathologic features and outcomes of metaplastic breast carcinoma: Comparison with invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Yonsei Med. J. 2010, 51, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.; Kostrzewa, C.E.; Zhang, Z.; O’Brien, D.A.R.; Mueller, B.A.; Cuaron, J.J.; Xu, A.J.; Bernstein, M.B.; McCormick, B.; Powell, S.N. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast: Matched cohort analysis of recurrence and survival. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 199, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polamraju, P.; Haque, W.; Cao, K.; Verma, V.; Schwartz, M.; Klimberg, V.S.; Hatch, S.; Niravath, P.; Butler, E.B.; Teh, B.S. Comparison of outcomes between metaplastic and triple-negative breast cancer patients. Breast 2020, 49, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primers | Sequence (5′-3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ACTB F | TGGCACCACACCTTCTACAA | Sammarco et al., 2020 [19] |

| ACTB R | CCAGAGGCGTACAGGGATAG | |

| CCND1 F | ATCAAGTGTGACCCGGACTG | |

| CCND1 R | CTTGGGGTCCATGTTCTGCT | |

| CTGF F | CGAGCTAAATTCTGTGGAGT | Qi et al., 2005 [20] |

| CTGF R | CCATGTCTCCGTACATCTTC |

| Variable | N/Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 62.6 ± 14.7 |

| Menopause Status | 19 (43.2%) |

| Size (cm) | 3.7 ± 2.7 |

| TNM STAGE | |

| Ia | 8 (18.2%) |

| IIa | 21 (47.7%) |

| IIb | 10 (22.7%) |

| IIIa | 2 (4.5%) |

| IIIb | 1 (2.3%) |

| IIIc | 1 (2.3%) |

| IV | 1 (2.3%) |

| ER (+) | 4 (9.1%) |

| PR (+) | 4 (9.1%) |

| Her2 (+) | 1 (2.3%) |

| Ki67 (>15%) | 24 (54.5%) |

| MOLECULAR SUBTYPE | |

| TNBC | 38 (86.4%) |

| Luminal A | 1 (2.3%) |

| Luminal B | 4 (9.1%) |

| Luminal B HER2 | 1 (2.3%) |

| CHEMOTHERAPY | 38 (86.4%) |

| RADIOTHERAPY | 29 (65.9%) |

| GENETIC TEST | 2 (4.5%) |

| FAMILY HISTORY | 5 (11.4%) |

| HISTOLOGIC GRADE | |

| GRADE 2 | 6 (13.6%) |

| GRADE 3 | 38 (86.4%) |

| HISTOLOGIC SUBTYPE | |

| Squamous n (%) | 10 (22.7%) |

| Spindle cell n (%) | 8 (18.1%) |

| Mixed | 17 (38.6%) |

| MpBC with heterologous mesenchymal differentiation—Matrix-Producing n (%) | 9 (20.4%) |

| CCND1 | 3.9 (7.4%) |

| CTGF | 12.5 (22.4%) |

| NUCLEAR YAP/TAZ (+) EXPRESSION | 27 (61.4%) |

| CYTOPLASM YAP/TAZ (+) EXPRESSION | 33 (75%) |

| YAP/TAZ (+) Expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoplasm | p-Value | Nucleus | p-Value | |

| HISTOLOGICAL SUBTYPE | ||||

| Squamous | 6 (60%) | 0.588 | 7 (70.0%) | 0.180 |

| Spindle | 7 (87.5) | 6 (75.0%) | ||

| Mixed | 13 (76.5%) | 7 (41.2%) | ||

| MpBC with heterologous mesenchymal differentiation—Matrix-Producing | 7 (77.8%) | 7 (77.8%) | ||

| MOLECULAR SUBTYPE | ||||

| TNBC | 28 (73.7%) | 0.195 | 23 (60.5%) | 0.468 |

| Luminal A | 1 (100.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | ||

| Luminal B | 4 (100.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | ||

| Luminal B-like | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| TOTAL | 33 (75.0%) | 27 (61.4%) | ||

| CCND1 (Mean ± SD) | p-Value | CTGF (Mean ± SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HISTOLOGICAL SUBTYPE | ||||

| Squamous | 4.67 ± 7.65 | 0.483 | 5.71 ± 2.29 | 0.853 |

| Spindle | 0.8 ± 0.83 | 7.28 ± 12.44 | ||

| Mixed | 5.55 ± 9.9 | 15.61 ± 33.82 | ||

| MpBC with heterologous mesenchymal differentiation—Matrix-Producing | 2.91 ± 3.62 | 13.44 ± 11.09 | ||

| MOLECULAR SUBTYPE | ||||

| TNBC | 4.14 ± 7.8 | 0.683 | 13.87 ± 23.37 | 0.608 |

| Luminal A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Luminal B | 1.43 ± 1.30 | 2.05 ± 0.97 | ||

| Luminal B-like | N/A | N/A | ||

| TAZ/YAP NUCLEUS (+) EXPRESSION | ||||

| (+) | 2.93 ± 5.64 | 0.253 | 8.89 ± 10.48 | 0.236 |

| (−) | 5.56 ± 9.49 | 19.53 ± 36.79 | ||

| TAZ/YAP CYTOPLASM EXPRESSION | ||||

| (+) | 3.96 ± 8.27 | 0.987 | 11.98 ± 24.97 | 0.892 |

| (−) | 3.91 ± 3.94 | 12.85 ± 9.32 | ||

| (−) | 5.56 ± 9.49 | 19.53 ± 36.79 |

| Variable | HR | 95.0% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| AGE | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 0.796 |

| MENOPAUSE STATUS | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Yes | 1.31 | 0.56 | 3.08 | 0.531 |

| SIZE (cm) | 1.04 | 0.88 | 1.22 | 0.652 |

| TNM STAGE | ||||

| Ia | reference | |||

| IIa | 0.11 | 0.01 | 1.15 | 0.066 |

| IIb | 0.14 | 0.02 | 1.21 | 0.074 |

| IIIa | 0.14 | 0.01 | 1.37 | 0.091 |

| IIIb | 0.16 | 0.01 | 2.88 | 0.215 |

| IIIc | 1.83 | 0.11 | 31.78 | 0.678 |

| IV | 0.85 | 0.05 | 13.78 | 0.906 |

| ER | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 0.93 | 0.22 | 3.99 | 0.923 |

| PR | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 0.86 | 0.20 | 3.69 | 0.839 |

| Her2 | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 0.05 | 0.00 | 944.48 | 0.544 |

| Ki67 | ||||

| <15% | Reference | |||

| >15% | 1.39 | 0.49 | 3.98 | 0.540 |

| MOLECULAR SUBTYPE | ||||

| TNBC | reference | |||

| Luminal A | 5.64 | 0.69 | 46.03 | 0.107 |

| Luminal B | 0.98 | 0.23 | 4.22 | 0.973 |

| Luminal B-like | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.983 |

| CHEMOTHERAPY | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Yes | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.92 | 0.033 |

| RADIOTHERAPY | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Yes | 0.86 | 0.36 | 2.06 | 0.739 |

| GENETIC TESTING (+) | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 4.13 | 0.90 | 18.93 | 0.680 |

| FAMILY HISTORY | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 0.42 | 0.96 | 1.83 | 0.068 |

| HISTOLOGIC GRADE | ||||

| GRADE 2 | reference | |||

| GRADE 3 | 1.53 | 0.52 | 4.53 | 0.443 |

| HISTOLOGIC SUBTYPE | ||||

| Squamous | reference | |||

| Spindle cell | 1.10 | 0.24 | 4.89 | 0.908 |

| Mixed | 1.99 | 0.62 | 6.36 | 0.247 |

| MpBC with heterologous mesenchymal differentiation—Matrix-Producing | 1.99 | 0.52 | 7.57 | 0.313 |

| TAZ/YAP NUCLEUS (+) EXPRESSION | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 1.52 | 0.62 | 3.74 | 0.361 |

| TAZ/YAP CYTOPLASM EXPRESSION | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 1.45 | 0.49 | 4.30 | 0.502 |

| CCND1 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 1.03 | 0.208 |

| CTGF | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.797 |

| Variable | HR | 95.0% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| AGE | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 0.672 |

| MENOPAUSE STATUS | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Yes | 1.51 | 0.55 | 4.15 | 0.429 |

| SIZE (CM) | 1.10 | 0.92 | 1.32 | 0.298 |

| TNM STAGE | ||||

| Ia | reference | |||

| IIa | 0.87 | 0.22 | 3.51 | 0.850 |

| IIb | 1.11 | 0.22 | 5.54 | 0.896 |

| IIIa | 2.09 | 0.22 | 20.23 | 0.524 |

| IIIb | 33.11 | 2.21 | 495.54 | 0.011 |

| IIIc | 9.61 | 0.86 | 108.04 | 0.067 |

| IV | 16.33 | 1.31 | 203.61 | 0.030 |

| ER | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 0.66 | 0.09 | 5.01 | 0.689 |

| PR | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 0.64 | 0.08 | 4.83 | 0.663 |

| Her2 | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 0.05 | 0.00 | 22,666.23 | 0.647 |

| Ki67 | ||||

| <15% | reference | |||

| >15% | 0.97 | 0.28 | 3.34 | 0.967 |

| MOLECULAR SUBTYPE | ||||

| TNBC | reference | |||

| Luminal A | 9.84 | 1.09 | 88.36 | 0.041 |

| Luminal B | 0.71 | 0.09 | 5.43 | 0.743 |

| Luminal B-like | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | 0.988 |

| CHEMOTHERAPY | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Yes | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.033 |

| RADIOTHERAPY | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Yes | 0.77 | 0.28 | 2.13 | 0.620 |

| GENETIC TESTING | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 1.56 | 0.20 | 11.89 | 0.669 |

| FAMILY HISTORY | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 0.03 | 0.00 | 9.35 | 0.237 |

| HISTOLOGIC GRADE | ||||

| GRADE 2 | reference | |||

| GRADE 3 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 1.33 | 0.142 |

| HISTOLOGIC SUBTYPE | ||||

| Squamous | reference | |||

| Spindle cell | 1.56 | 0.22 | 11.10 | 0.657 |

| Mixed | 3.77 | 0.79 | 17.87 | 0.095 |

| MpBC with heterologous mesenchymal differentiation—Matrix-Producing | 3.98 | 0.70 | 22.59 | 0.119 |

| TAZ/YAP NUCLEUS EXPRESSION | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 2.11 | 0.68 | 6.56 | 0.196 |

| TAZ/YAP CYTOPLASM EXPRESSION | ||||

| Negative | reference | |||

| Positive | 2.46 | 0.56 | 10.85 | 0.234 |

| CCND1 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 1.06 | 0.272 |

| CTGF | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 0.573 |

| RECURENCE | ||||

| No | reference | |||

| Yes | 107.42 | 1.65 | 6996.04 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papamattheou, E.; Papatheodoridi, A.; Katsaros, I.; Bletsa, G.; Nonni, A.; Dimitrakakis, C.; Haidopoulos, D.; Andrikopoulou, A.; Papakosta, A.; Marinopoulos, S.; et al. The Hippo Pathway in Metaplastic Breast Carcinoma: Prognostic Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121060

Papamattheou E, Papatheodoridi A, Katsaros I, Bletsa G, Nonni A, Dimitrakakis C, Haidopoulos D, Andrikopoulou A, Papakosta A, Marinopoulos S, et al. The Hippo Pathway in Metaplastic Breast Carcinoma: Prognostic Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121060

Chicago/Turabian StylePapamattheou, Eleni, Alkistis Papatheodoridi, Ioannis Katsaros, Garyfalia Bletsa, Afroditi Nonni, Constantine Dimitrakakis, Dimitrios Haidopoulos, Angeliki Andrikopoulou, Areti Papakosta, Spyridon Marinopoulos, and et al. 2025. "The Hippo Pathway in Metaplastic Breast Carcinoma: Prognostic Significance and Therapeutic Implications" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121060

APA StylePapamattheou, E., Papatheodoridi, A., Katsaros, I., Bletsa, G., Nonni, A., Dimitrakakis, C., Haidopoulos, D., Andrikopoulou, A., Papakosta, A., Marinopoulos, S., Giannos, A., Koura, S., Papachatzopoulou, E., Papapanagiotou, I. K., Metaxas, G. I., Giannakaki, A.-G., Dimopoulos, M.-A., & Zagouri, F. (2025). The Hippo Pathway in Metaplastic Breast Carcinoma: Prognostic Significance and Therapeutic Implications. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121060