Novel Synthetic Steroid Derivatives: Target Prediction and Biological Evaluation of Antiandrogenic Activity

Abstract

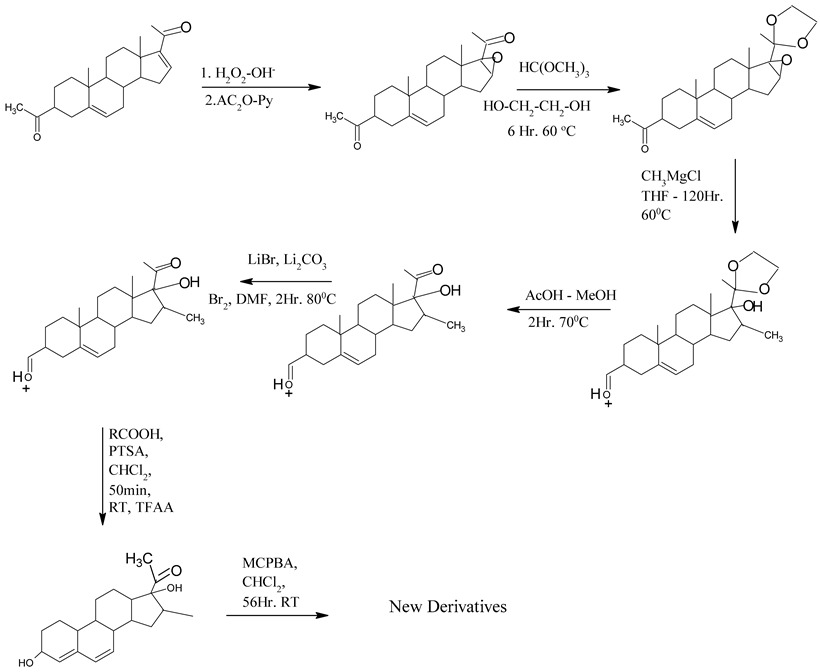

1. Introduction

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

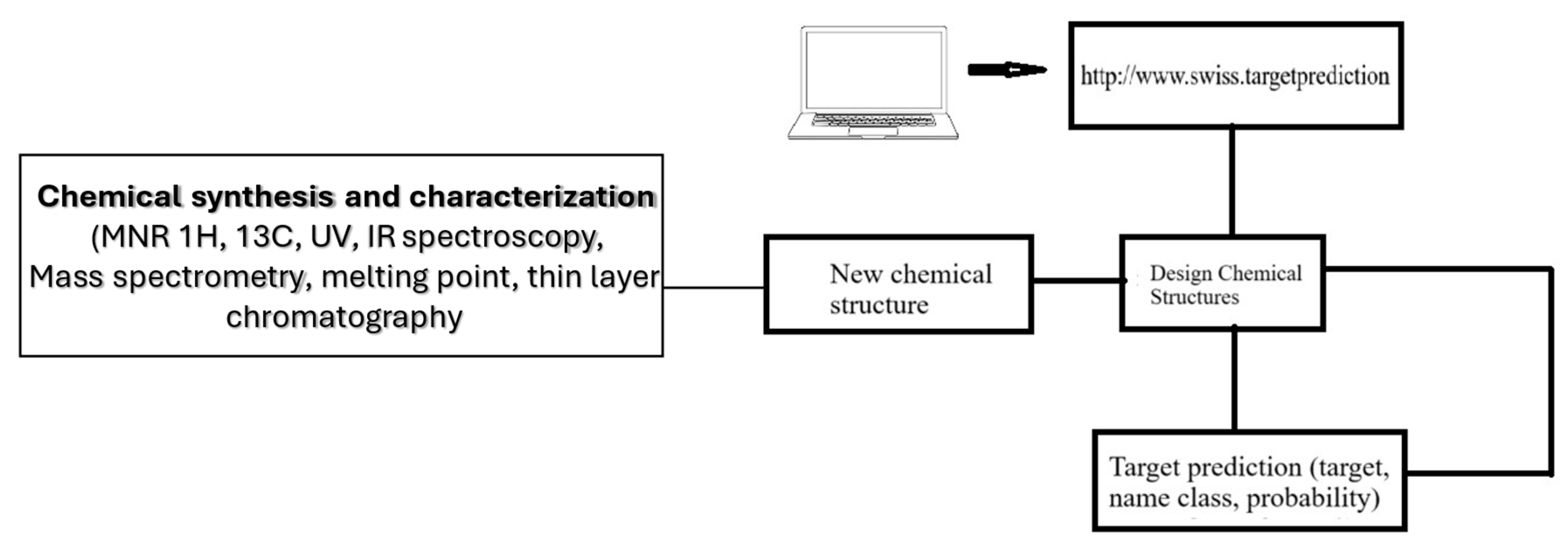

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

2.2. Investigational Products

2.3. Experimental Design

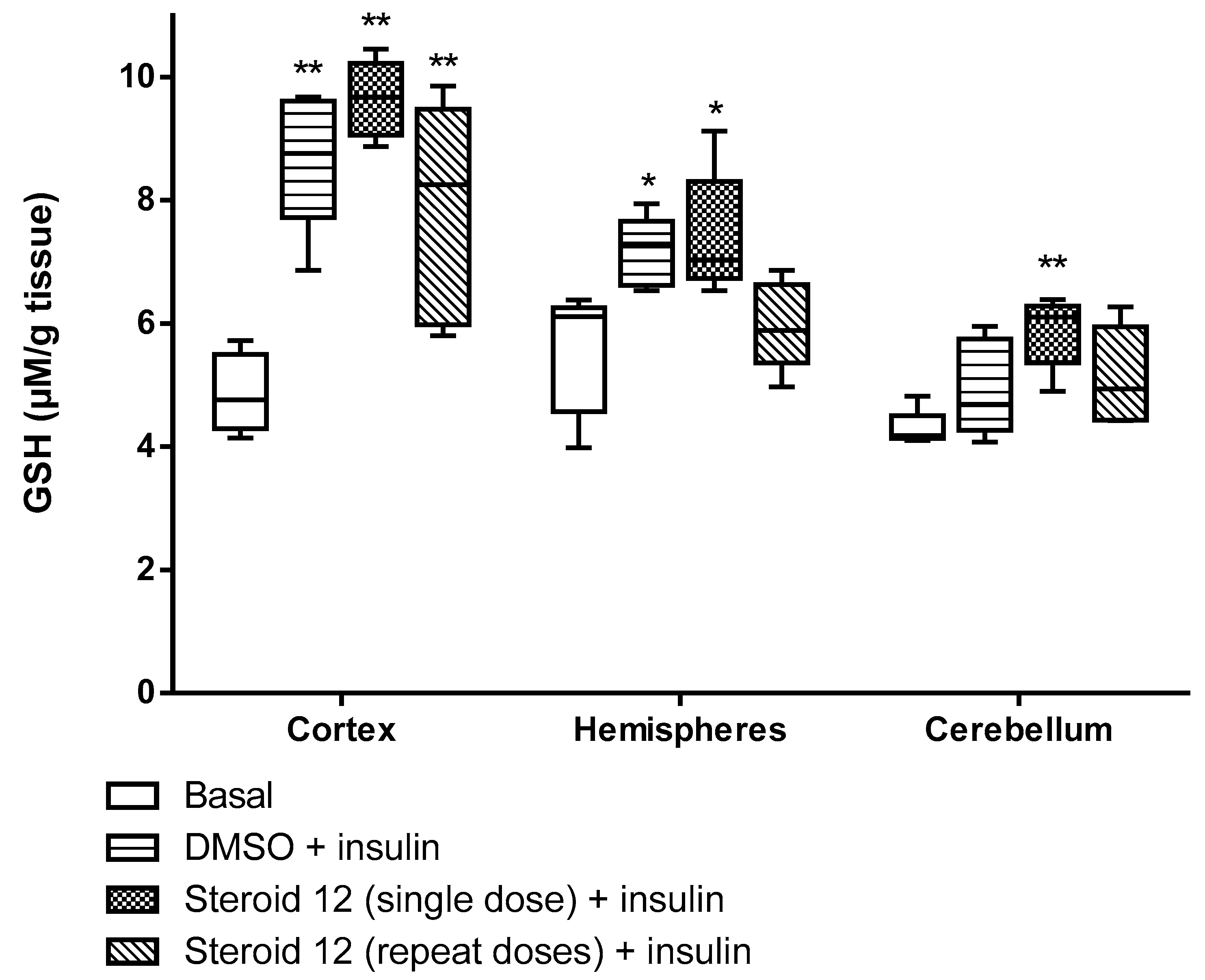

2.4. GSH Assessment

2.5. 5-HIAA Assay and Assessment

2.6. Dopamine (DA) Assay and Assessment

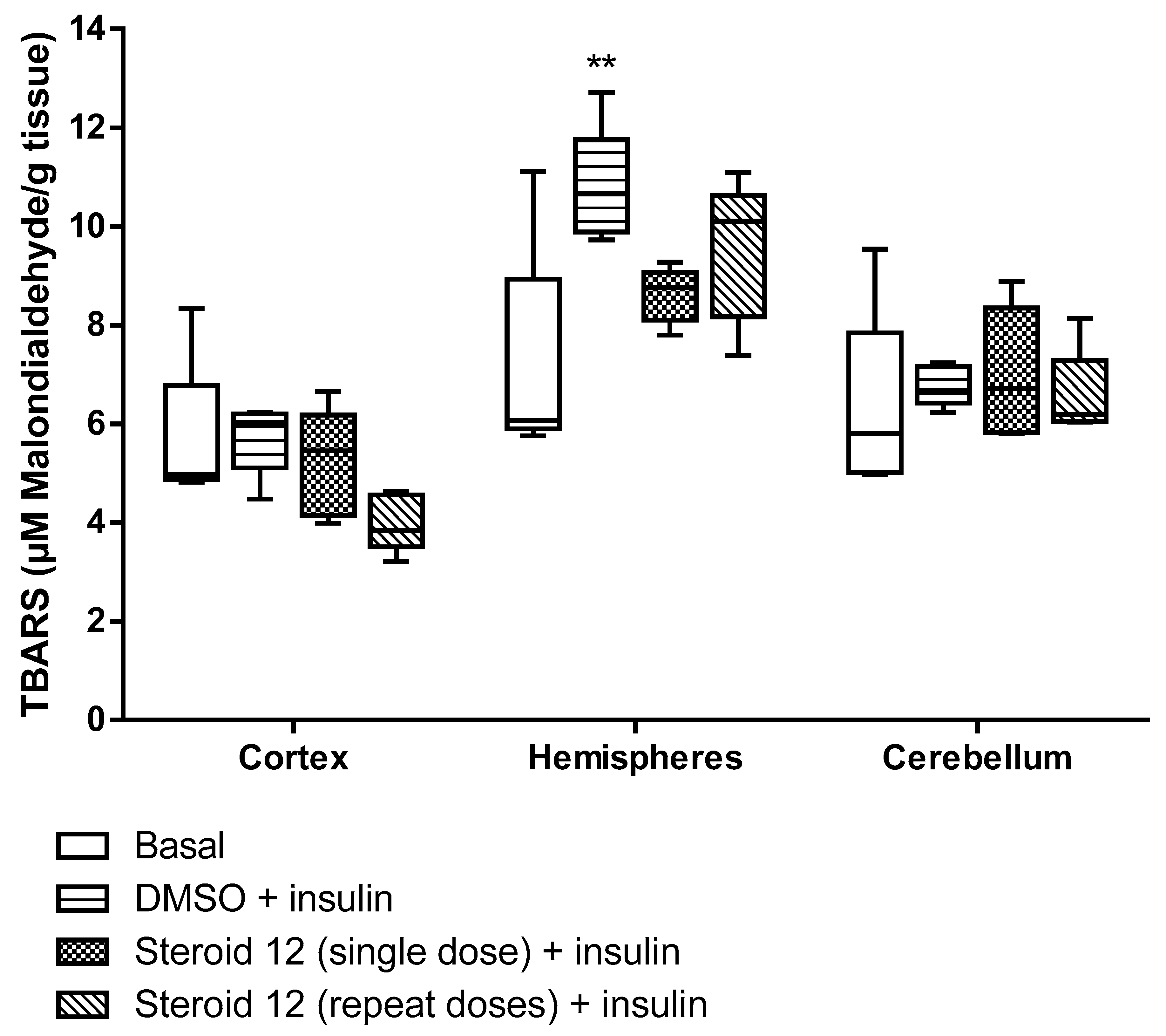

2.7. Assessment of Lipid Peroxidation

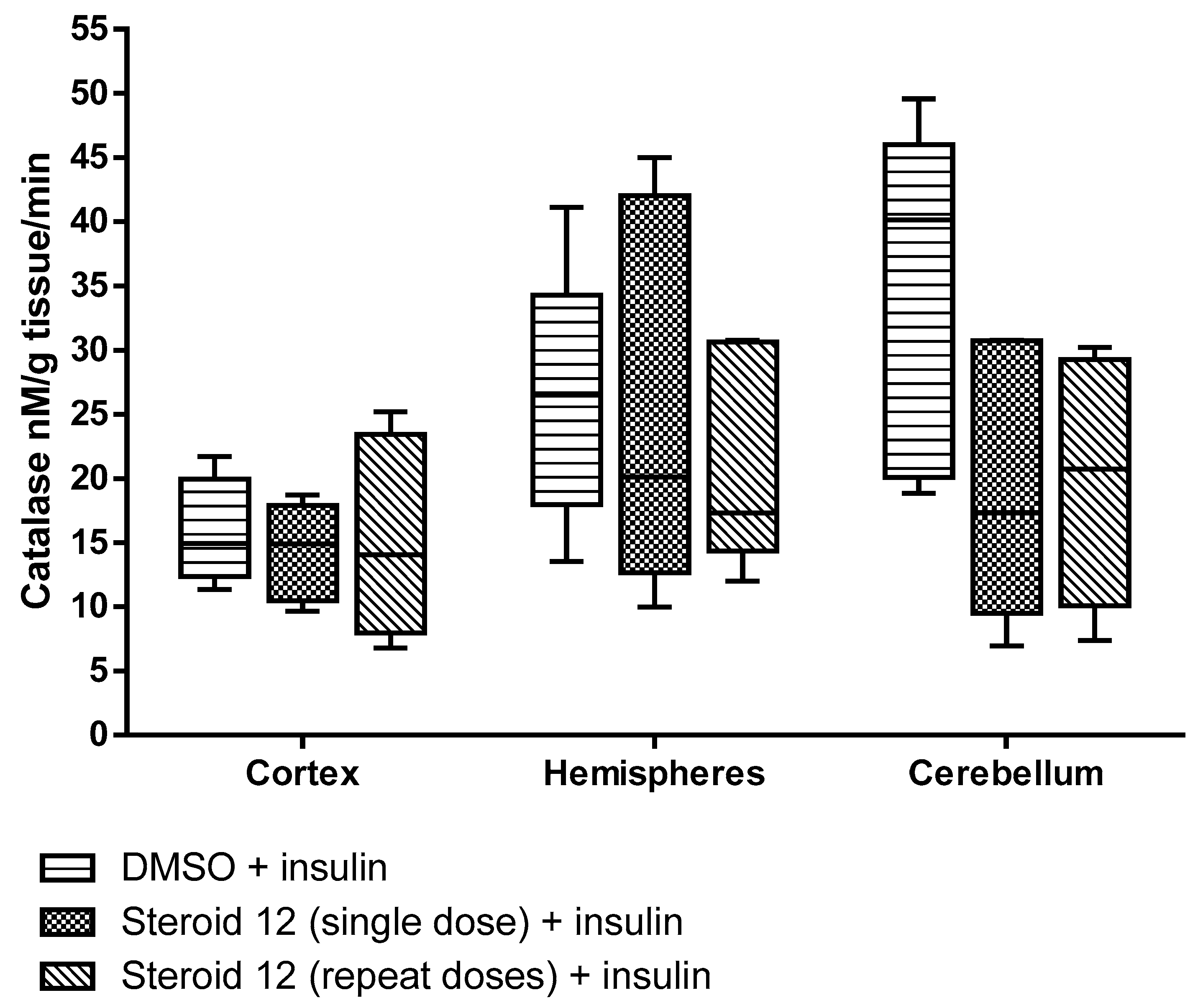

2.8. Measurement of Catalase (CAT)

2.9. Cerebral Cortex Homogenates

2.10. Purification of Myelin

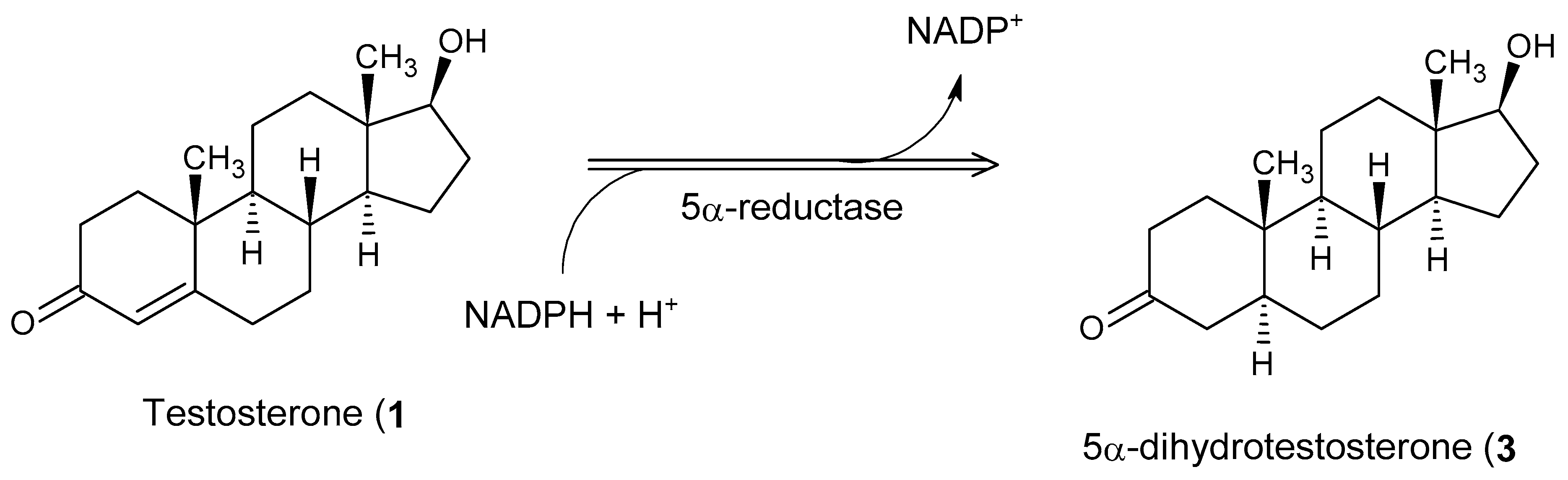

2.11. Kinetic Enzymatic of 5α-Reductase Assay

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calderón, G.D.; Barragán, M.G.; Espitia, V.I.; Hernández, G.E.; Santamaría, A.D.; Juárez, O.H. Effect of testosterone and steroids homologues on indolamines and lipid peroxidation in rat brain. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 94, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowszowicz, I. Antiandrogens. Mechanisms and paradoxical effects. Ann. Endocrinol. 1989, 50, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gillatt, D. Antiandrogen treatments in locally advanced prostate cancer: Are they all the same? J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 132, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, R.; Sun, T.; Zhao, L.; Liu, F.; Ren, S.; Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Gao, X.; Xu, C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of combined androgen blockade with antiandrogen for advanced prostate cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2019, 26, e39–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moguilewsky, M.; Bouton, M.M. How the study of the biological activities of antiandrogens can be oriented towards the clinic. J. Steroid Biochem. 1988, 31, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, E.L.; Song, Y.; Malik, V.S.; Liu, S. Sex differences of endogenous sex hormones and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2006, 295, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markkula, P.S.; Lyons, D.; Yueh, C.-Y.; Riches, C.; Hurst, P.; Fielding, B.; Heisler, L.K.; Evans, M.L. Intracerebroventricular Catalase Reduces Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity and Increases Responses to Hypoglycemia in Rats. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 4669–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Wei, J.; Yuan, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, G.; Liu, X. Sex hormones in COVID-19 severity: The quest for evidence and influence mechanisms. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, K.O.; Khaidarova, R.R.; Khabibullina, R.H.; Stytsenko, E.S.; Filosofova, V.I.; Nuriakhmetova, I.R.; Hisameeva, E.M.; Vazhorov, G.S.; Khaibullin, F.R.; Ivanova, E.A.; et al. Testosterone and Alzheimer’s disease. Probl. Endokrinol. 2022, 68, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiff, M.; Sidi, H.; Masiran, R.; Kumar, J.; Das, S.; Hatta, N.H.; Alfonso, C. Hypersexuality As a Neuropsychiatric Disorder: The Neurobiology and Treatment Options. Curr. Drug Targets 2018, 19, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neunzig, J.; Sánchez-Guijo, A.; Mosa, A.; Hartmann, M.F.; Geyer, J.; Wudy, S.A.; Bernhardt, R. A steroidogenic pathway for sulfonated steroids: The metabolism of pregnenolone sulfate. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 144, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Rabe, T. Hormonal antiandrogens in acne treatment. J. German Soc. Dermatol. 2010, 8, S60–S74. [Google Scholar]

- Sakkiah, S.; Ng, H.W.; Tong, W.; Hong, H. Structures of androgen receptor bound with ligands: Advancing understanding of biological functions and drug discovery. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2016, 20, 1267–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Kim, J.; Dalton, J.T. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nonsteroidal androgen receptor ligands. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 1641–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjes, F.J.; Debruyne, F.M.; Del Moral, P.F.; Geboers, A.D. Ketoconazole high dose in management of hormonally pretreated patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Dutch South-Eastern Urological Cooperative Group. Urology 1989, 33, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albany, C.; Hahn, N.M. Heat shock and other apoptosis-related proteins as therapeutic targets in prostate cancer. Asian J. Androl. 2014, 16, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolvenbag, G.J.; Iversen, P.; Newling, D.W. Antiandrogen monotherapy: A new form of treatment for patients with prostate cancer. Urology 2001, 58, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, M.; Yu, X.; Dong, L.; Li, J.; Chang, D.; Yang, F. The Effect of COVID-19 on Male Sex Hormones: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traish, A.M. Sex steroids and COVID-19 mortality in women. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massard, C. Targeting Continued Androgen Receptor Signaling in Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 3876–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.; Akamatsu, S.; Tsukahara, S.; Nagakawa, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Eto, M. Androgen receptor mutations for precision medicine in prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2022, 29, R143–R155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Marcoccia, D.; Narciso, L.; Mantovani, A.; Lorenzetti, S. Intracellular Distribution and Biological Effects of Phytochemicals in a Sex Steroid-Sensitive Model of Human Prostate Adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2014, 24, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolkowska, D.; Dhir, A.; Krishnan, K.; Covey, D.F.; Rogawski, M.A. Anticonvulsant potencies of the enantiomers of the neurosteroids androsterone and etiocholanolone exceed those of the natural forms. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 3325–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Singh, V.; Nagampalli, V.; Ponsky, L.E.; Li, C.R.; Chao, H.; Gupta, S. Ligand-gated ion channels as potential biomarkers for ADT-mediated cognitive decline in prostate cancer patients. Mol. Carcinog. 2024, 63, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, E.; Bratoeff, E.; Cabeza, M.; Ramirez, E.; Quiroz, A.; Heuze, I. Steroid 5alpha-reductase inhibitors. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2003, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xie, G.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Du, J.; Cui, H. Effects of dihydrotestosterone on synaptic plasticity of hippocampus in male SAMP8 mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, L.; Primka, R.L.; Berman, C.; Vergult, G.; Gabriel, M.; Pierre-Malice, M.; Gibelin, B. Comparison of finasteride (Proscar), a 5 alpha reductase inhibitor, and various commercial plant extracts in in vitro and in vivo 5 alpha reductase inhibition. Prostate 1993, 22, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Y.; Blanco, A.; Tosti, A. Androgenetic Alopecia: An Update of Treatment Options. Drugs 2016, 76, 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartsch, G.; Rittmaster, R.S.; Klocker, H. Dihydrotestosterone and the role of 5 alpha-reductase inhibitors in benign prostatic hiperplasia. Urologe A 2002, 41, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliescu, R.; Campos, L.A.; Schlegel, W.-P.; Morano, I.; Baltatu, O.; Bader, M. Androgen receptor independent cardiovascular action of the antiandrogen flutamide. J. Mol. Med. 2003, 81, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agis-Balboa, R.C.; Guidotti, A.; Pinna, G. 5α-reductase type I expression is downregulated in the prefrontal cortex/Brodmann’s area 9 (BA9) of depressed patients. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 3569–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melcangi, R.C.; Celotti, F.; Ballabio, M.; Castano, P.; Poletti, A.; Milani, S.; Martini, L. Ontogenetic development of the 5 alpha-reductase in the rat brain: Cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, purified myelin and isolated oligodendrocytes. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1988, 44, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haupt, C.; Henke, M.; Kutschmar, A.; Hauser, B.; Baldinger, S.; Saenz, S.R.; Schreiber, G. Antiandrogen or estradiol treatment or both during hormone therapy in transitioning transgender women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, L.M.; Nolan, B.J.; Zajac, J.D.; Cheung, A.S. A systematic review of antiandrogens and feminization in transgender women. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021, 94, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burinkul, S.; Panyakhamlerd, K.; Suwan, A.; Tuntiviriyapun, P.; Wainipitapong, S. Anti-Androgenic Effects Comparison Between Cyproterone Acetate and Spironolactone in Transgender Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, N.E.; Sofer, Y.; Yaish, I.; Serebro, M.; Tordjman, K.; Greenman, Y. Low-Dose Cyproterone Acetate Treatment for Transgender Women. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliere, M.; Coche, M.; Lacroix, C.; Riggi, J.; Coyette, M.; Coulie, J.; Galant, C.; Fellah, L.; Leconte, I.; Maiter, D.; et al. Effects of Hormones on Breast Development and Breast Cancer Risk in Transgender Women. Cancers 2022, 15, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, L.; Buljubasic, A.M.; Budoff, M.J.; Copeland, L.A.; Jackson, N.J.; Jasuja, G.K.; Gornbein, J.; Reue, K. Gender-Affirming Hormone Treatment and Metabolic Syndrome Among Transgender Veterans. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2419696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Margaill, I.; Zhang, S.; Labombarda, F.; Coqueran, B.; Delespierre, B.; Liere, P.; Marchand-Leroux, C.; O’Malley, B.W.; Lydon, J.P. Progesterone receptors: A key for neuroprotection in experimental stroke. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3747–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammouz, G.; Lecanu, L.; Papadopoulos, V. Oxidative Stress-Mediated Brain Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) Formation in Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2011, 2, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.Y.; He, X.Y.; Isaacs, C.; Dobkin, C.; Miller, D.; Philipp, M. Roles of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10 in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 143, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitku, J.; Starka, L.; Bicikova, M.; Hill, M.; Heracek, J.; Sosvorova, L.; Hampl, R. Endocrine disruptors and other inhibitors of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 and 2: Tissue-specific consequences of enzyme inhibition. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 155, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaili, J.; Boisvert, M.; Longpré, F.; Carange, J.; Le Gall, C.; Martinoli, M.G. Brassinosteroids and analogs as neuroprotectors: Synthesis and structure-activity relationships. Steroids 2012, 77, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, D.C.; Bratoeff, E.; Riveros, A.C.; Brizuela, N.O.; Mejia, G.B.; Olguin, H.J.; Garcia, E.H.; Cruz, E.G. Effect of two antiandrogens as protectors of prostate and brain in a Huntington’s animal model. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.C.; Lee, W.R.; Armstrong, A.J. Second generation anti-androgens and androgen deprivation therapy with radiation therapy in the definitive management of high-risk prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2023, 26, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

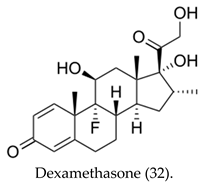

- Sinha, S.; Rosin, N.L.; Arora, R.; Labit, E.; Jaffer, A.; Cao, L.; Farias, R.; Nguyen, A.P.; de Almeida, L.G.N.; Dufour, A.; et al. Dexamethasone modulates immature neutrophils and interferon programming in severe COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giotis, E.S.; Cil, E.; Brooke, G.N. Use of Antiandrogens as Therapeutic Agents in COVID-19 Patients. Viruses 2022, 14, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Datusalia, A.K.; Kumar, A. Use of steroids in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 914, 174579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhivanov, R.V.; Andreeva, E.N.; Melnichenko, G.A.; Mokrysheva, N.G. Androgens and Antiandrogens influence on COVID-19 disease in men. Probl. Endokrinol. 2020, 66, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hissin, P.J.; Hilf, R. A fluorometric method for determination of oxidized and reduced glutathione in tissue. Anal. Biochem. 1974, 4, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, O.; Palmskog, G.; Hultman, E. Quantitative determination of 5-hydroxyindole- 3-acetic acid in body fluids by HPLC. Clin. Chim. Acta 1977, 79, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, F.; Lecomte-Joulin, V.; Falcy, C.; Dupeyron, J.P. Automatic liquid chromatography of urinary dopamine. J. Chromatogr. 1984, 311, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutteridge, J.M.; Halliwell, B. The measurement and mechanism of lipid peroxidation in biological systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1990, 15, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, D.C.; Brizuela, N.O.; Herrera, M.O.; Olguín, H.J.; García, E.H.; Peraza, A.V.; Mejía, G.B. Oleic acid protects against oxidative stress exacerbated by cytarabine and doxorubicin in rat brain. Mini-Revi Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 1491–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Hadwan, M.H. Simple spectrophotometric assay for measuring catalase activity in biological tissues. BMC Biochem. 2018, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poletti, A.; Celotti, F.; Melcangi, R.C.; Ballabio, M.; Martini, L. Kinetic properties of the 5 alpha-reductase of testosterone in the purified myelin, in the subcortical white matter and in the cerebral cortex of the male rat brain. J. Steroid Biochem. 1990, 35, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castilla-Serna, L. Practical Manual of Statistics for Health Sciences Manual Práctico de Estadística para las Ciencias de la Salud, 1st ed.; Trillas: Mexico, DF, Mexico, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Do Anti-androgens Have Potential as Therapeutics for COVID-19? Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqab114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.; Abbassi, B.; Su, C.; Singh, M.; Cunningham, R.L. Oxidative stress defines the neuroprotective or neurotoxic properties of androgens in immortalized female rat dopaminergic neuronal cells. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 4281–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiota, M.; Yokomizo, A.; Naito, S. Oxidative stress and androgen receptor signaling in the development and progression of castration-resistant prostate cáncer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

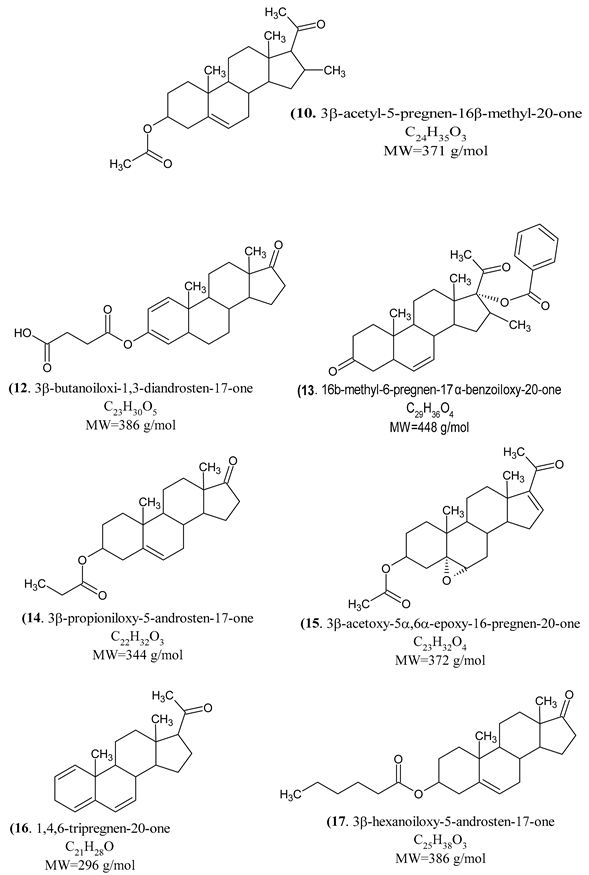

| Steroid or Structure | Target Prediction |

|---|---|

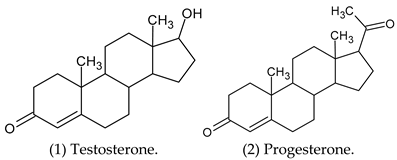

| Testosterone (1) | Androgen receptor, Cytochrome P450 19A1, Glucocorticoid receptor, Corticosteroid-binding globulin, Sigma opioid receptor, Testis-specific androgen-binding protein. |

| Progesterone (2) | Steroid 5α-reductase 2, Cytochrome P450 2C9, Cytochrome P450 2C19. |

| 5α-Dihydrotestosterone (3) | Androgen receptor, Cytochrome P450 19A1, Corticosteroid-binding globulin, Testis-specific androgen-binding protein, Estradiol 17-β-dehydrogenase 3, Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase. |

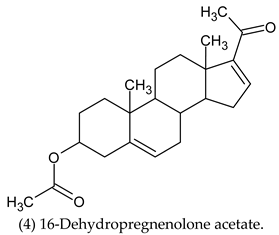

| 16-Dehydropregnenolone Acetate (4) | Cytochrome P450 17A1. |

| (5) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1, Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, Glycogen synthase kynase-3 beta, Androgen receptor. |

| (6) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1, Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, Purinergic receptor P2Y1, Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase, Orexin receptor 2, Nitric oxide synthase inducible. |

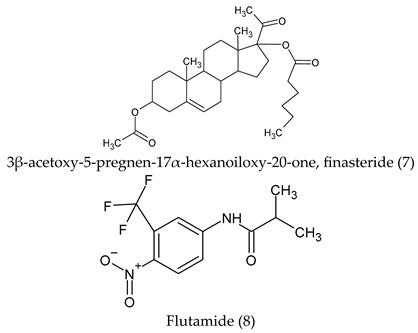

| Finasteride (7) | Androgen receptor, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Glucocorticoid receptor, Progesterone receptor, Corticosteroid-binding globulin, Sigma opioid receptor, Testis-specific androgen-binding protein, Cytochrome P450 19A1. |

| Flutamide (8) | Androgen receptor, serotonin 6 (5-HT6) receptor. |

| (9) | Glucocorticoid receptor, Corticosteroid-binding globulin, Testis-specific androgen-binding protein, Androgen receptor, Mineralocorticoid receptor, progesterone receptor. |

| (10) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1. |

| Cyproterone acetate (11) | Androgen receptor, Glucocorticoid receptor, Adenoside A1 receptor, µu Opioid receptor, Cytochrome P450 2C19. |

| (12) | Thromboxane A2 receptor, Prostanoid DP receptor, Thromboxane A synthase, G protein-coupled receptor 44, Epoxide hydratase, steroid 5α-reductase 2, Prostanoid EP4 receptor |

| (13) | Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B, T-cell protein-tyrosine phosphatase, Cytochrome P450 19A1, Androgen receptor, steroid 5α-reductase 1, 3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/delta 5-4 Isomerase type 1. |

| (14) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, Steroid 5α-reductase 2, Androgen receptor, Progesteron receptor. |

| (15) | Androgen receptor, Cytochrome P450 19A1, Progesterone receptor, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Cytochrome P450 17A1, Carboxylesterase 2, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 |

| (16) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Melatonin receptor 1A, Melatonin receptor 1B, Epoxide Hydrolase 1, Epoxide Hydratase, Estradiol 17-β-dehydrogenase 2. |

| (17) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, Nitric oxide synthase inducible, Steroid 5α-reductase 2, Androgen receptor, Progesterone receptor. |

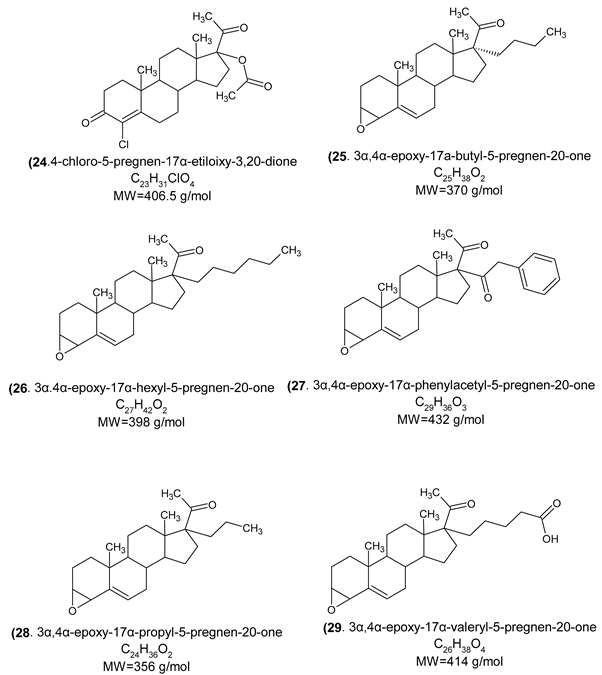

| (18) | Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase 2, Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2. |

| (19) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, Acetylcholinesterase, Glucocorticoid receptor, Mineralocorticoid receptor. |

| (20) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, Androgen receptor, Glucocorticoid receptor, Progesterone receptor. |

| (21) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, Androgen receptor, Glucocorticoid receptor, Progesterone receptor, Nitric oxide synthase inducible. |

| (22) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, Glucocorticoid receptor, Progesterone receptor, Nitric oxide synthase inducible. |

| (23) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1, Glucocorticoid receptor, Progesterone receptor, Testis-specific androgen-binding protein, Nitric oxide synthase inducible. |

| (24) | Androgen receptor, progesterone receptor, Glucocorticoid receptor, Cytochrome P450 2C19, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Testis-specific androgen-binding protein, Steroid 5α-reductase 2. |

| (25) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Progesterone receptor, Androgen receptor, Epoxide hydratase, Endoplasmin. |

| (26) | Cytochrome P450 17A1, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Progesterone receptor, Androgen receptor, Epoxide hydratase, Cytochrome P450 19A1. |

| (27) | Orexin receptor 1, Orexin receptor 2, Cathepsin S, Calciun sensing receptor, Cyclin-dependent Kinase 1, Phosphodiesterase 10A, Vasopressin V2 receptor. |

| (28) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Cytochrome P450 17A1, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Progesterone receptor, Androgen receptor, Estrogen receptor α, Estrogen receptor β. |

| (29) | Cytochrome P450 19A1, Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, Thromboxane A2 receptor, Progesterone receptor, Androgen receptor, Mineralocorticoid receptor. |

| (30) | Progesterone receptor, Androgen receptor, Estrogen receptor β, Cytochrome P450 2C19, Mineralocorticoid receptor, Glucocorticoid receptor. |

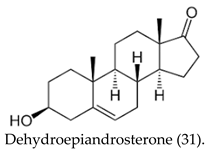

| (31) | Testis-specific androgen-binding protein, Glucose-6-Phosphate 1-dehydrogenase, Corticosteroid binding globulin, Cytochrome P450 19A1, Estrogen receptor β, Androgen receptor, Glucocorticoid receptor, Cytochrome P450 17A1. |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Basal (No treatment) | Insulin + DMSO | Insulin + Steroid 12 (single doses) | Insulin + Steroid 12 (four doses) |

| Steroids | 5α-Reductase ± SD | Km ± SD | Vmax ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| (30) Spironolactone C24H32O4S MW = 416.57 g/mol | 0.305 ± 0.006 | 0.0309 ± 0.006 | 0.304 ± 0.007 |

| (16) 1,4,6-tripregnen-20-one C21H28O MW = 296 g/mol | 0.739 ± 0.01 | 0.378 ± 0.03 | 0.767 ± 0.01 |

| (22) 3β-acetoxy-5-pregnen-17α-hexanoiloxy-20-one C29H44O5 MW = 472 g/mol | 0.615 ± 0.16 | 0.288 ± 0.27 | 0.607 ± 0.16 |

| (24) 4-chloro-5-pregnen-17α-etiloixy-3,20-dione C23H31ClO4 MW = 406.5 g/mol | 0.369 ± 0.002 | 0.010 ± 0.008 | 0.370 ± 0.003 |

| (26) 3α,4α-epoxy-17α-hexyl-5-pregnen-20-one C27H42O2 MW = 398 g/mol | 0.406 ± 0.008 | 0.063 ± 0.009 | 0.409 ± 0.006 |

| (27) 3α,4α-epoxy-17α-phenylacetyl-5-pregnen-20-one C29H36O3 MW = 432 g/mol | 0.434 ± 0.007 | 0.075 ± 0.01 | 0.434 ± 0.007 |

| (29) 3α,4α-epoxy-17α-valeryl-5-pregnen-20-one C26H38O4 MW = 414 g/mol | 0.390 ± 0.008 | 0.020 ± 0.01 | 0.392 ± 0.008 |

| (13) 16α-methyl-6-pregnen-17α-benzoiloxy-20-one C29H36O4 MW = 448 g/mol | 0.381 ± 0.01 | 0.142 ± 0.014 | 0.382 ± 0.01 |

| Experimental Groups | Triglycerides mg/dL | Glucose mg/dL |

|---|---|---|

| Basal | 128.6 ± 29 | 159.2 ± 10 * |

| DMSO + Insulin | 107.4 ± 4 | 31.0 ± 3 |

| Steroid 12 (SD) + Insulin | 94.0 ± 31 | 31.8 ± 8 |

| Steroid 12 (RD) + Insulin | 116.6 ± 9 | 35.6 ± 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calderón Guzmán, D.; Osnaya Brizuela, N.; Juárez Olguín, H.; Ortiz Herrera, M.; Valenzuela Peraza, A.; Hernández Garcia, E.; Chávez Riveros, A.; Calderón Morales, S.; Rojas Ochoa, A.; Silva Ortiz, A.; et al. Novel Synthetic Steroid Derivatives: Target Prediction and Biological Evaluation of Antiandrogenic Activity. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121059

Calderón Guzmán D, Osnaya Brizuela N, Juárez Olguín H, Ortiz Herrera M, Valenzuela Peraza A, Hernández Garcia E, Chávez Riveros A, Calderón Morales S, Rojas Ochoa A, Silva Ortiz A, et al. Novel Synthetic Steroid Derivatives: Target Prediction and Biological Evaluation of Antiandrogenic Activity. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121059

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalderón Guzmán, David, Norma Osnaya Brizuela, Hugo Juárez Olguín, Maribel Ortiz Herrera, Armando Valenzuela Peraza, Ernestina Hernández Garcia, Alejandra Chávez Riveros, Sarai Calderón Morales, Alberto Rojas Ochoa, Aylin Silva Ortiz, and et al. 2025. "Novel Synthetic Steroid Derivatives: Target Prediction and Biological Evaluation of Antiandrogenic Activity" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121059

APA StyleCalderón Guzmán, D., Osnaya Brizuela, N., Juárez Olguín, H., Ortiz Herrera, M., Valenzuela Peraza, A., Hernández Garcia, E., Chávez Riveros, A., Calderón Morales, S., Rojas Ochoa, A., Silva Ortiz, A., Santes Palacios, R., Dorado Gonzalez, V. M., & García Ortega, D. (2025). Novel Synthetic Steroid Derivatives: Target Prediction and Biological Evaluation of Antiandrogenic Activity. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121059