Cancer Vaccines: Molecular Mechanisms, Clinical Progress, and Combination Immunotherapies with a Focus on Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cancer Vaccines

2.1. Nucleic Acid-Based Vaccines

2.1.1. DNA Vaccines

2.1.2. RNA Vaccines

2.2. Peptide-Based Cancer Vaccines

2.3. Tumor Cell-Derived Vaccine

2.3.1. Whole-Cell-Based Cancer Vaccines

2.3.2. Tumor Cell Lysate-Based Cancer Vaccine

2.4. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicle-Based Vaccines (TEVs)

2.4.1. Tumor Cell-Derived Exosome Vaccines

2.4.2. Tumor-Derived Microvesicle-Based Vaccine

2.5. Virus-Based Cancer Vaccine

2.6. Bacteria-Based Cancer Vaccine

3. Tumor Microenvironment: Cellular Composition

4. Cancer Vaccine Resistance: Mechanisms

5. Key Components and Factors Affecting the Efficiency of Cancer Vaccines

5.1. Selection of Target Antigens and Neoantigen-Based Cancer Immunotherapy

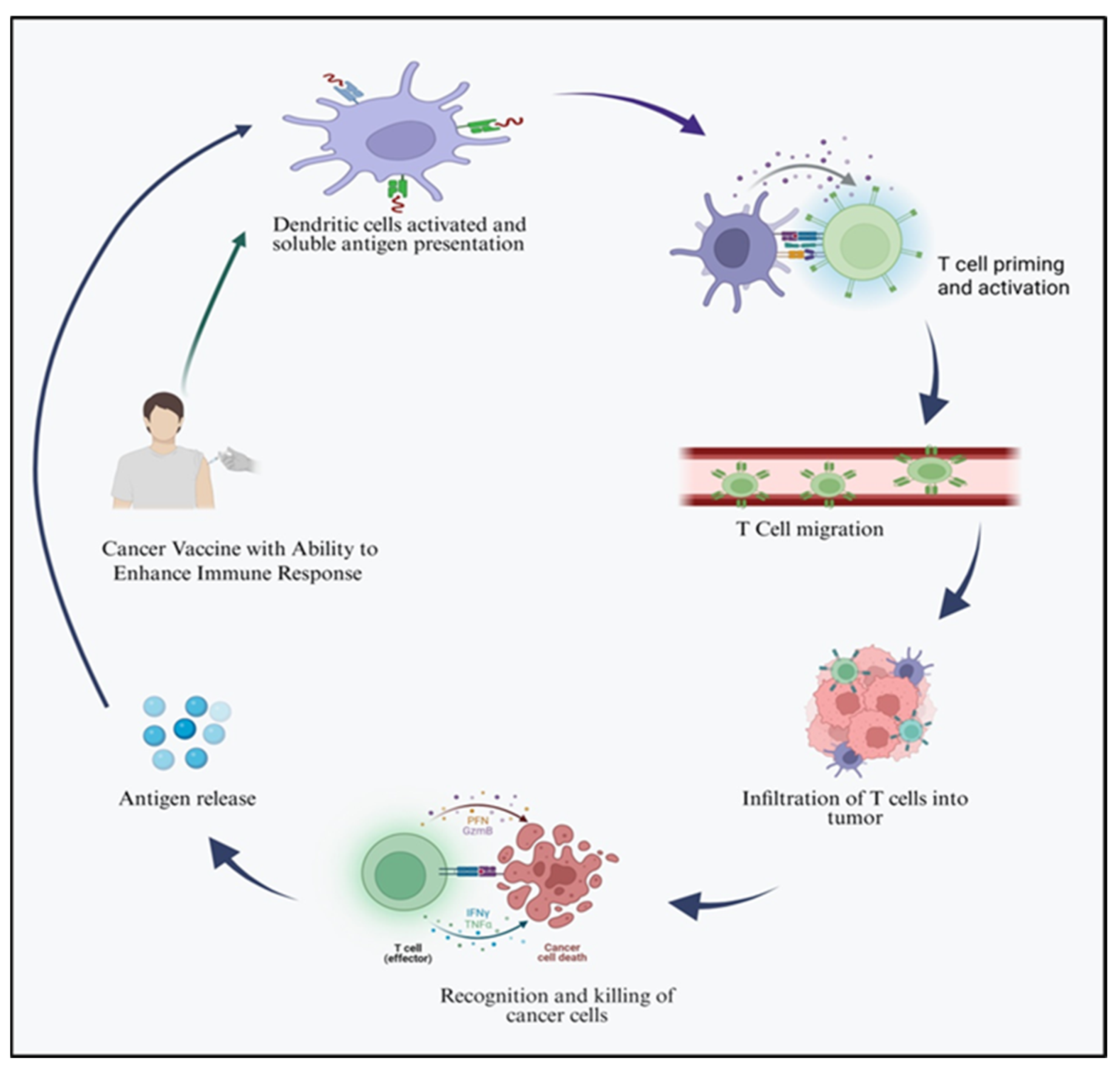

5.2. Activation of Immune Response

5.3. Role of Adjuvants

5.4. Administration Routes of Cancer Vaccines

6. Engineering Strategies to Enhance Tumor Cell-Derived Vaccine

6.1. Genetic Engineering

6.2. Surface Engineering

6.3. Internal Cargo Loading

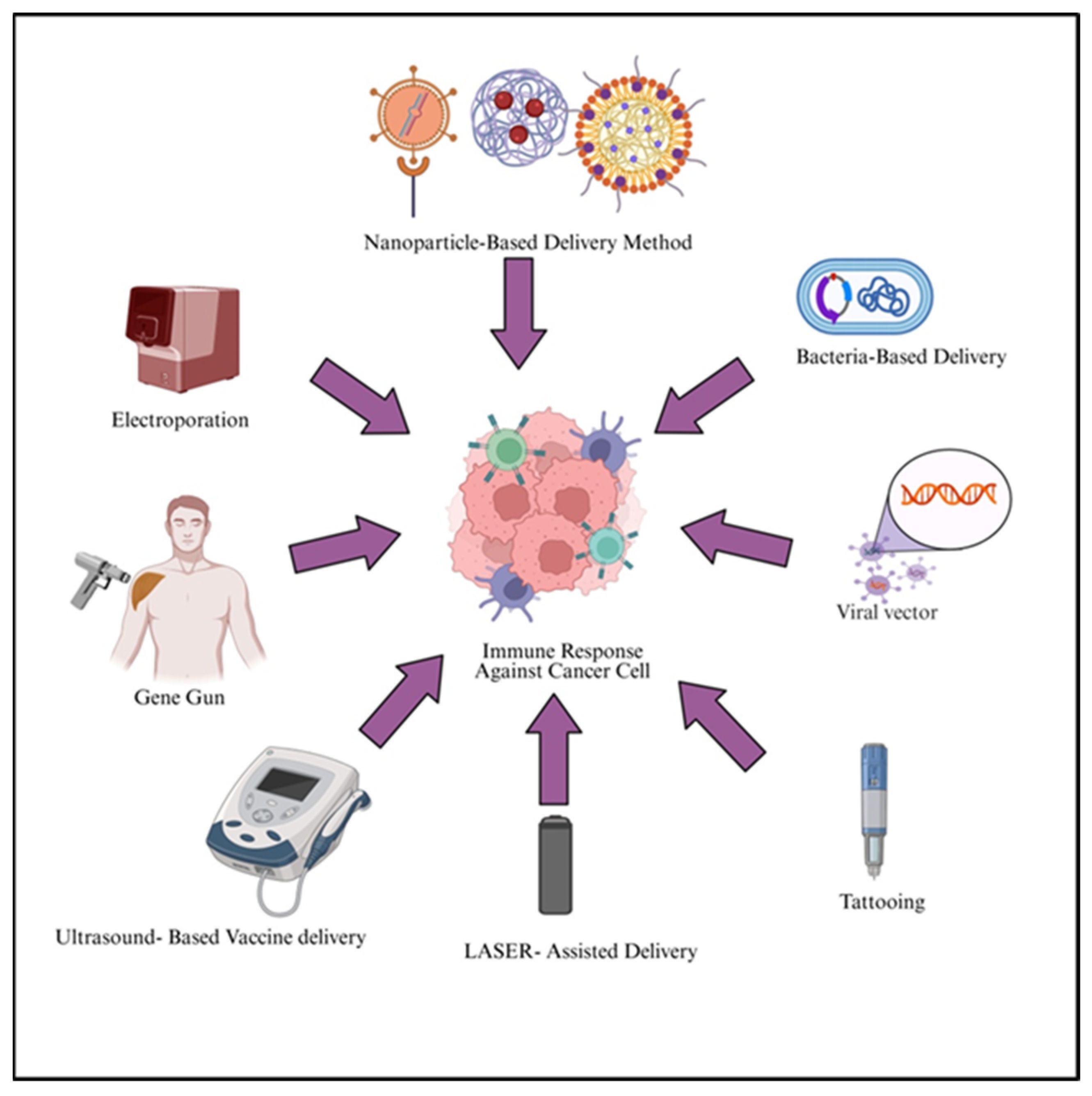

7. Delivery Methods

| Method | Principle | Methodology | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation | Introduce nucleic acids into cells either in vitro or in vivo by applying electric pulse to induce temporary and reversible permeabilization of cell membrane | DNA plasmid is injected intramuscularly or intradermally, short electric pulses applied via electrodes | High efficiency | Painful, possible damage to the skin and muscle tissue at the injection site | [156] |

| Gene-gun delivery methods | DNA-coated microparticles penetrate cells via high pressure gas burst | Plasmid DNA precipitated on gold/tungsten particles loaded in cartridges and shot into skin or tissue using helium pressure. | Low cytotoxicity, less tissue damage | Less efficiency | [157] |

| Ultrasound (Sonoporation) | Cavitaton induced by ultrasound lead to pore formation and ultimately allows nucleic acid entry | DNA/NP suspension applied to tissue/cells, ultrasound generates microbubbles facilitating uptake | Non-invasive, enhance APC activation | Optimization needed | [158,159] |

| LASER assisted Delivery | Low energy LASER waves cause micropore formations, allowing nucleic acid entry | Target tissue irradiated with LASER pulse before and after DNA application and DNA becomes diffused into permeabilized cells | High efficiency, localized targeting | Tissue heating | [160] |

| Tattooing | Rapid puncturing by tattoo needles delivers DNA intradermally into APC-rich skin | DNA solution applied, tattoo machine punctures skin, delivering DNA directly to dermis | Strong immune response, fast delivery | Pain, cosmetic concern | [161] |

| Viral vector mediated method | Recombinant virus deliver antigen encoding genes into host cells | Genes inserted into adenovirus or lentivirus are injected to infect APCs or tumor cells | High immunogenicity, persistent response | Safety risk, might be pre-existing immunity present | [162] |

| Bacterial vectors mediated delivery | Attenuated bacteria invade APCs and deliver antigens genes/proteins | Listeria/salmonella engineered with tumor antigens administrated systemically or orally and stimulate innate and adaptive immunity | Tumor targeting, strong activation | Safety and toxicity issues | [163] |

| Nanoparticle based delivery method | Nanocarriers encapsulate and protect DMA/RNA/Protein enabling controlled release | Lipid/polymer nanoparticles prepared by solvent methods encapsulate antigens and are injected for APC uptake | Stability, controlled release | Complex manufacturing | [164] |

7.1. Electroporation

7.2. Gene Gun

7.3. Ultrasound-Based Method

7.4. LASER-Assisted Delivery Method

7.5. Tattooing

7.6. Biological Methods

7.6.1. Viral Systems

7.6.2. Bacterial Delivery System

7.7. Nanoparticle-Based Delivery of Cancer Vaccines

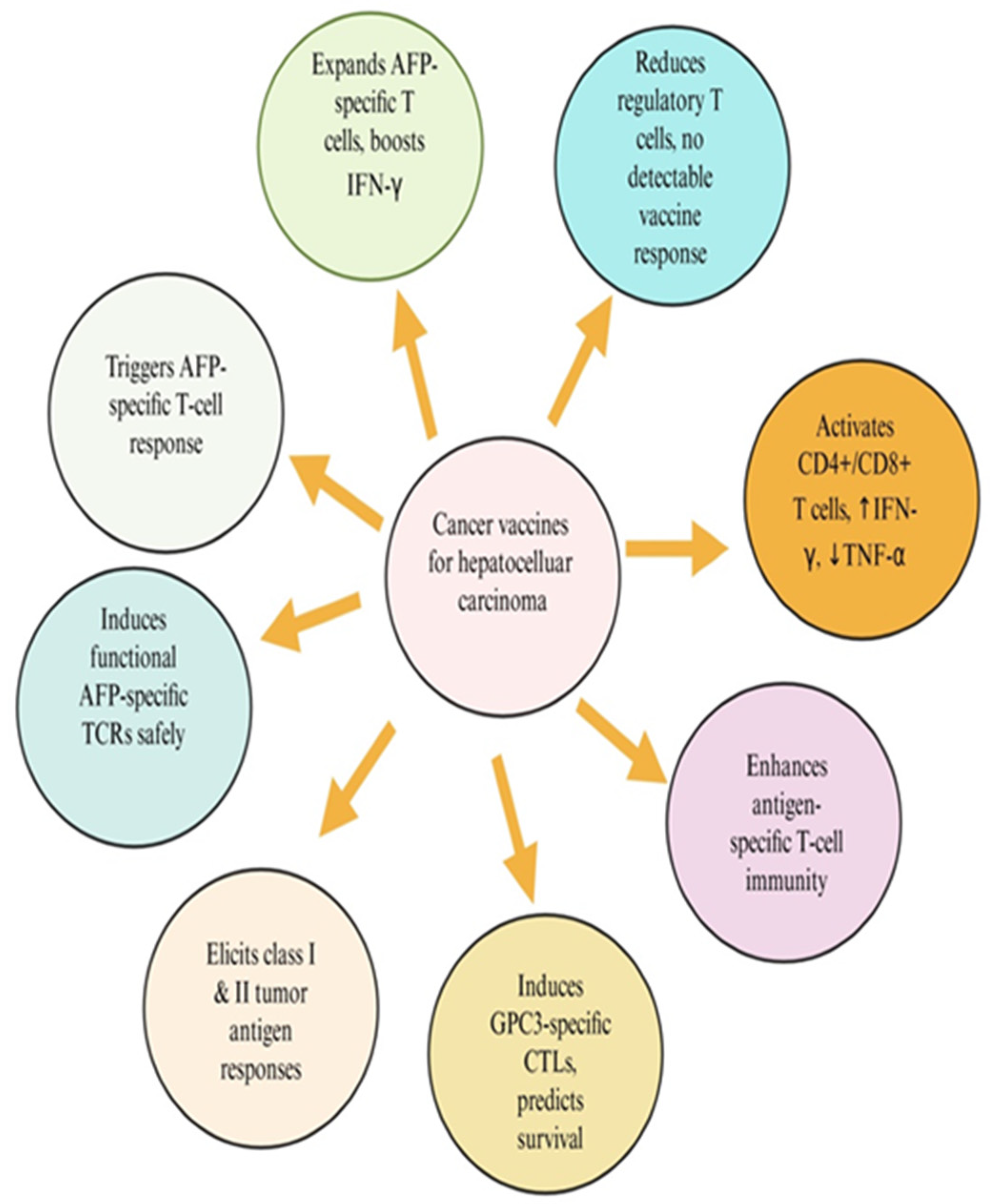

8. Clinical Applications of Cancer Vaccines in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

8.1. HCC-Specific Tumor Antigens and Their Molecular Characteristics

8.1.1. Glypican-3

8.1.2. Alpha-Fetoprotein

8.1.3. Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (hTERT)

8.1.4. Cancer–Testis Antigens

8.1.5. Other Emerging Antigens

9. Molecular Targets of HCC Treatment

10. Combinational Approaches to Enhance Cancer Vaccine Efficacy for HCC Treatment

11. Translational Pipeline for Developing HCC Vaccines

12. Challenges and Limitations in HCC Vaccine Development

13. Future Perspectives

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| CART | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| OMVs | Outer membrane vesicles |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| NK | Natural killer |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells (Tregs) |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 |

| PD-1 | Programmed death 1 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-35 | Interleukin-35 |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| TAAs | Tumor-associated antigens |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| ACTs | Adoptive cell transfers |

| CD4+ | Cluster of Differentiation 4+ T cells |

| CD8+ | Cluster of Differentiation 8+ T cells |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| 5′ UTR | 5′ untranslated region |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| TCVs | Tumor cell-derived vaccines |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| TEXs | Tumor-derived exosomes |

References

- Alrumaihi, F.; Rahmani, A.H.; Prabhu, S.V.; Kumar, V.; Anwar, S. The Role of Plant-Derived Natural Products as a Regulator of the Tyrosine Kinase Pathway in the Management of Lung Cancer. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.H.; Babiker, A.Y.; Anwar, S. Hesperidin, a bioflavonoid in cancer therapy: A review for a mechanism of action through the modulation of cell signaling pathways. Molecules 2023, 28, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrumaihi, F. Role of Liquid Biopsy for Early Detection, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Monitoring of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anwar, S.; Almatroudi, A.; Alsahli, M.A.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Natural products: Implication in cancer prevention and treatment through modulating various biological activities. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 2025–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhong, P.; Wei, P. Living Bacteria: A New Vehicle for Vaccine Delivery in Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Tian, X.; Wei, X. Cancer vaccines: Current status and future directions. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Banda, J.S.; Gangane, S.; Raza, F.; Massarelli, E. Current Development of Therapeutic Vaccines in Lung Cancer. Vaccines 2025, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hao, P. Therapeutic vaccine strategies in cancer: Advances, challenges, and future directions. Clin. Cancer Bull. 2025, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cheng, S.; Cai, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Yang, F.; Chen, K.; Qiu, M. The Current Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines Landscape in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 155, 1909–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M. The use of RNA-based treatments in the field of cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Poznańska, J.; Fechner, F.; Michalska, N.; Paszkowska, S.; Napierała, A.; Mackiewicz, A. Cancer Vaccine Therapeutics: Limitations and Effectiveness-A Literature Review. Cells 2023, 12, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, N.; Lapointe, R.; Lerouge, S. Biomaterials for enhanced immunotherapy. APL Bioeng. 2022, 6, 041502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan, T.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, W.; Dong, C. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: Advancements, challenges, and prospects. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liao, H.C.; Liu, S.J. Advances in nucleic acid-based cancer vaccines. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 32, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergati, M.; Intrivici, C.; Huen, N.Y.; Schlom, J.; Tsang, K.Y. Strategies for cancer vaccine development. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 596432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cui, Z. DNA vaccine. Adv. Genet. 2005, 54, 257–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fioretti, D.; Iurescia, S.; Fazio, V.M.; Rinaldi, M. DNA vaccines: Developing new strategies against cancer. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 2010, 174378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lopes, A.; Vandermeulen, G.; Préat, V. Cancer DNA vaccines: Current preclinical and clinical developments and future perspectives. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tiptiri-Kourpeti, A.; Spyridopoulou, K.; Pappa, A.; Chlichlia, K. DNA vaccines to attack cancer: Strategies for improving immunogenicity and efficacy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 165, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, R.G.; Robinson, H.L. DNA vaccines: A review of developments. BioDrugs 1997, 8, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattergoon, M.A.; Robinson, T.M.; Boyer, J.D.; Weiner, D.B. Specific immune induction following DNA-based immunization through in vivo transfection and activation of macrophages/antigen-presenting cells. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 5707–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Xia, F.; Chen, H.; Cui, B.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, J.; Luo, M. A guide to nucleic acid vaccines in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases and cancers: From basic principles to current applications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 633776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigar, S.; Shimosato, T. Cooperation of oligodeoxynucleotides and synthetic molecules as enhanced immune modulators. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Petrovsky, N. Molecular mechanisms for enhanced DNA vaccine immunogenicity. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2016, 15, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shariati, A.; Khezrpour, A.; Shariati, F.; Afkhami, H.; Yarahmadi, A.; Alavimanesh, S.; Kamrani, S.; Modarressi, M.H.; Khani, P. DNA vaccines as promising immuno-therapeutics against cancer: A new insight. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1498431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Magoola, M.; Niazi, S.K. Current Progress and Future Perspectives of RNA-Based Cancer Vaccines: A 2025 Update. Cancers 2025, 17, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suschak, J.J.; Williams, J.A.; Schmaljohn, C.S. Advancements in DNA vaccine vectors, non-mechanical delivery methods, and molecular adjuvants to increase immunogenicity. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2017, 13, 2837–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Nuffel, A.M.; Wilgenhof, S.; Thielemans, K.; Bonehill, A. Overcoming HLA restriction in clinical trials: Immune monitoring of mRNA-loaded DC therapy. OncoImmunology 2012, 1, 1392–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Pei, J.; Xu, S.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. Recent advances in mRNA cancer vaccines: Meeting challenges and embracing opportunities. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1246682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines—A new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kowalski, P.S.; Rudra, A.; Miao, L.; Anderson, D.G. Delivering the Messenger: Advances in Technologies for Therapeutic mRNA Delivery. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, L.A.; Kommareddy, S.; Maione, D.; Uematsu, Y.; Giovani, C.; Berlanda Scorza, F.; Otten, G.R.; Yu, D.; Mandl, C.W.; Mason, P.W.; et al. Self-amplifying mRNA vaccines. Adv. Genet. 2015, 89, 179–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafri, G.; Gartner, J.J.; Zaks, T.; Hopson, K.; Levin, N.; Paria, B.C.; Parkhurst, M.R.; Yossef, R.; Lowery, F.J.; Jafferji, M.S.; et al. mRNA vaccine-induced neoantigen-specific T cell immunity in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 5976–5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tendeloo, V.; Ponsaerts, P.; Berneman, Z.N. mRNA-based gene transfer as a tool for gene and cell therapy. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2007, 9, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bevers, S.; Kooijmans, S.A.A.; Van de Velde, E.; Evers, M.J.W.; Seghers, S.; Gitz-Francois, J.; van Kronenburg, N.C.; Fens, M.H.; Mastrobattista, E.; Hassler, L.; et al. mRNA-LNP vaccines tuned for systemic immunization induce strong antitumor immunity by engaging splenic immune cells. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 3078–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Qi, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, N.; Nan, F.; Zhang, H.; Tian, M.; Li, C.; Lu, H.; Jin, N. mRNA vaccines encoding the HA protein of influenza A H1N1 virus delivered by cationic lipid nanoparticles induce protective immune responses in mice. Vaccines 2020, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Tang, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, K.; Fan, N.; Xiao, W.; Zheng, Q.; Li, G.; Teng, Y.; Wu, M.; et al. mRNA-based therapeutics: Powerful and versatile tools to combat diseases. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vormehr, M.; Schrors, B.; Boegel, S.; Lower, M.; Tureci, O.; Sahin, U. Mutanome engineered RNA immunotherapy: Towards patient-centered tumor vaccination. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 595363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Che, X. Advancements and Challenges in Peptide-Based Cancer Vaccination: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Vaccines 2024, 12, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Tang, H.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Li, J. Peptide-based therapeutic cancer vaccine: Current trends in clinical application. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tay, R.E.; Richardson, E.K.; Toh, H.C. Revisiting the Role of CD4(+) T Cells in Cancer Immunotherapy-New Insights Into Old Paradigms. Cancer Gene Ther. 2020, 28, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijker, M.S.; van den Eeden, S.J.; Franken, K.L.; Melief, C.J.; van der Burg, S.H.; Offringa, R. Superior Induction of Anti-Tumor CTL Immunity by Extended Peptide Vaccines Involves Prolonged, DC-Focused Antigen Presentation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 38, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney, J.; del Guercio, M.F.; Southwood, S.; Engelhard, V.H.; Appella, E.; Rammensee, H.G.; Falk, K.; Rötzschke, O.; Takiguchi, M.; Kubo, R.T. Several HLA Alleles Share Overlapping Peptide Specificities. J. Immunol. 1995, 154, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwood, S.; Sidney, J.; Kondo, A.; del Guercio, M.F.; Appella, E.; Hoffman, S.; Kubo, R.T.; Chesnut, R.W.; Grey, H.M.; Sette, A. Several Common HLA-DR Types Share Largely Overlapping Peptide Binding Repertoires. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 3363–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, A.J.; Burgess-Brown, N.A.; Jiang, S. Beyond Just Peptide Antigens: The Complex World of Peptide-Based Cancer Vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 696791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, F.; Aróstica, M.; Román, T.; Beltrán, D.; Gauna, A.; Albericio, F.; Cárdenas, C. Peptides, solid-phase synthesis and characterization: Tailor-made methodologies. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 64, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaka, R.R. How do adjuvants enhance immune responses? Elife 2024, 13, e101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Facciolà, A.; Visalli, G.; Laganà, A.; Di Pietro, A. An Overview of Vaccine Adjuvants: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Vaccines 2022, 10, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reddy, S.T.; Swartz, M.A.; Hubbell, J.A. Targeting dendritic cells with biomaterials: Developing the next generation of vaccines. Trends Immunol. 2006, 27, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, A.E.; Titball, R.; Williamson, D. Vaccine delivery using nanoparticles. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2013, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Aziz, N.; Poh, C.L. Development of Peptide-Based Vaccines for Cancer. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 9749363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hashemi, F.; Razmi, M.; Tajik, F.; Zöller, M.; Dehghan Manshadi, M.; Mahdavinezhad, F.; Tiyuri, A.; Ghods, R.; Madjd, Z. Efficacy of Whole Cancer Stem Cell-Based Vaccines: A Systematic Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Stem Cells 2023, 41, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Meng, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhao, Y.; Irwin, D.M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Tai, Z.; Chen, Z. Tumor cell-derived vaccines: Advances, challenges, and future prospects. Interdiscip. Med. 2025, 3, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copier, J.; Dalgleish, A. Overview of Tumor Cell–Based Vaccines. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 25, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi Najafabadi, S.A.; Bolhassani, A.; Aghasadeghi, M.R. Tumor Cell-Based Vaccine: An Effective Strategy for Eradication of Cancer Cells. Immunotherapy 2022, 14, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Alcover, K.; Carpenter, E.; Thomas, K.; Krum, J.; Nissen, A.; Van Decar, S.; Smolinsky, T.; Valdera, F.; Vreeland, T.; et al. Utility of cell-based vaccines as cancer therapy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2024, 20, 2323256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, M. The Mechanism of Action of Cancer Therapeutic Vaccines and Their Application Prospects. Trans. Mater. Biotechnol. Life Sci. 2024, 3, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Jiang, A. Dendritic Cells and CD8 T Cell Immunity in Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hato, L.; Vizcay, A.; Eguren, I.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Rodríguez, J.; Gállego Pérez-Larraya, J.; Sarobe, P.; Inogés, S.; Díaz de Cerio, A.L.; Santisteban, M. Dendritic Cells in Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Yam, J.W.P.; Mao, X. Dendritic Cell Vaccines: A Shift from Conventional Approach to New Generations. Cells 2023, 12, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Najafi, S.; Mortezaee, K. Advances in dendritic cell vaccination therapy of cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenberk, L.; Belmans, J.; Van Woensel, M.; Riva, M.; Van Gool, S.W. Exploiting the immunogenic potential of cancer cells for improved dendritic cell vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2016, 6, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.L.; Ravindranathan, S.; Zaharoff, D.A. Current status of autologous breast tumor cell-based vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2014, 13, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diao, L.; Liu, M. Rethinking antigen source: Cancer vaccines based on whole tumor cell/tissue lysate or whole tumor cell. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2300121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestrinho, L.A.; Santos, R.R. Translational oncotargets for immunotherapy: From pet dogs to humans. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 172, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.A.; Bever, K.M.; Ho, W.J.; Fertig, E.J.; Niu, N.; Zhen, L.; Parkinson, R.M.; Durham, J.N.; Onners, B.; Ferguson, A.K.; et al. A Phase II Study of Allogeneic GM-CSF-Transfected Pancreatic Tumor Vaccine (GVAX) with Ipilimumab as Maintenance Treatment for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 5129–5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, W.; Zhou, K.; Lei, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H. Cancer vaccines: Platforms and current progress. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Verma, C.; Pawar, V.A.; Srivastava, S.; Tyagi, A.; Kaushik, G.; Shukla, S.K.; Kumar, V. Cancer Vaccines in the Immunotherapy Era: Promise and Potential. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Gao, J. Engineered tumor cell-derived vaccines against cancer: The art of combating poison with poison. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 22, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tomić, S.; Petrović, A.; Puač, N.; Škoro, N.; Bekić, M.; Petrović, Z.L.; Čolić, M. Plasma-Activated Medium Potentiates the Immunogenicity of Tumor Cell Lysates for Dendritic Cell-Based Cancer Vaccines. Cancers 2021, 13, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Diao, L.; Peng, Z.; Jia, Y.; Xie, H.; Li, B.; Ma, J.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, L.; Ding, D.; et al. Immunotherapy and Prevention of Cancer by Nanovaccines Loaded with Whole-Cell Components of Tumor Tissues or Cells. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.L.; Kandalaft, L.E.; Tanyi, J.; Hagemann, A.R.; Motz, G.T.; Svoronos, N.; Montone, K.; Mantia-Smaldone, G.M.; Smith, L.; Nisenbaum, H.L.; et al. A dendritic cell vaccine pulsed with autologous hypochlorous acid-oxidized ovarian cancer lysate primes effective broad antitumor immunity: From bench to bedside. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 4801–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berti, C.; Graciotti, M.; Boarino, A.; Yakkala, C.; Kandalaft, L.E.; Klok, H.A. Polymer Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery of Oxidized Tumor Lysate-Based Cancer Vaccines. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, e2100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.N.; Zhang, C.N.; Xu, R.; Niu, J.F.; Song, H.J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, W.W.; Wang, Y.M.; Li, C.; Wei, X.Q.; et al. Enhanced antitumor immunity by targeting dendritic cells with tumor cell lysate-loaded chitosan nanoparticles vaccine. Biomaterials 2017, 113, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, M.; Wang, G.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, X. Application of engineered extracellular vesicles for targeted tumor therapy. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cai, S.; Li, M.; Salma, K.I.; Zhou, X.; Han, F.; Chen, J.; Huyan, T. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Their Role in Immune Cells and Immunotherapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 5395–5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Syn, N.L.; Wang, L.; Chow, E.K.; Lim, C.T.; Goh, B.C. Exosomes in Cancer Nanomedicine and Immunotherapy: Prospects and Challenges. Trends Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseri, M.; Bozorgmehr, M.; Zöller, M.; Ranaei Pirmardan, E.; Madjd, Z. Tumor-derived exosomes: The next generation of promising cell-free vaccines in cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1779991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, T.J.; Guo, M.; Yang, X.; Zhu; Cao, X. Chemokine-containing exosomes are released from heat-stressed tumor cells via lipid raft-dependent pathway and act as efficient tumor vaccine. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Xiao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Pi, J.; Xu, H.; Zhao, H.; Xu, J.; Evans, C.E.; Jin, H. Advances in Anti-Tumor Treatments Targeting the CD47/SIRPα Axis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, B.; Yan, X.; Li, Y. Cancer Stem Cell for Tumor Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, J.A.; Kim, C.W. Introduction of the CIITA gene into tumor cells produces exosomes with enhanced anti-tumor effects. Exp. Mol. Med. 2011, 43, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fan, W.; Tian, X.D.; Huang, E.; Zhang, J.J. Exosomes from CIITA-transfected CT26 cells enhance anti- tumor effects. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Li, S.; Yi, M.; Li, N.; Wu, K. Roles of Microvesicles in Tumor Progression and Clinical Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 7071–7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pineda, B.; Sánchez García, F.J.; Olascoaga, N.K.; Pérez de la Cruz, V.; Salazar, A.; Moreno-Jiménez, S.; Hernández Pedro, N.; Márquez-Navarro, A.; Ortiz Plata, A.; Sotelo, J. Malignant Glioma Therapy by Vaccination with Irradiated C6 Cell-Derived Microvesicles Promotes an Antitumoral Immune Response. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tashiro, H.; Brenner, M.K. Immunotherapy against cancer-related viruses. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.L.; Liu, Z.; Sathaiah, M.; Ravindranathan, R.; Guo, Z.; He, Y.; Guo, Z.S. Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Larocca, C.; Schlom, J. Viral vector-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Cancer J. 2011, 17, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lundstrom, K. Viral Vector-Based Cancer Vaccines. Methods Mol. Biol. 2025, 2926, 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, K.Y.; Zaremba, S.; Nieroda, C.A.; Zhu, M.Z.; Hamilton, J.M.; Schlom, J. Generation of Human Cytotoxic T Cells Specific for Human Carcinoembryonic Antigen Epitopes from Patients Immunized with Recombinant Vaccinia-Cea Vaccine. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1995, 87, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, J.; Czerkinsky, C. Mucosal Immunity and Vaccines. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, S45–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Le, L.P.; Matthews, Q.L.; Han, T.; Wu, H.; Curiel, D.T. Derivation of a Triple Mosaic Adenovirus Based on Modification of the Minor Capsid Protein Ix. Virology 2008, 377, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seclì, L.; Leoni, G.; Ruzza, V.; Siani, L.; Cotugno, G.; Scarselli, E.; D’Alise, A.M. Personalized Cancer Vaccines Go Viral: Viral Vectors in the Era of Personalized Immunotherapy of Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Tintaya, W.; Chandra, D.; Jahangir, A.; Harris, M.; Casadevall, A.; Dadachova, E.; Gravekamp, C. Nontoxic radioactive Listeria (at) is a highly effective therapy against metastatic pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8668–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, N.; Javadi, M.M. Future prospects of bacteria-mediated cancer therapies: Affliction or opportunity? Microb. Pathog. 2022, 172, 105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Wen, Q.; Lin, S.; Wen, Q.; Lu, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, J.; Xiao, S.; et al. Bacteria-Driven Tumor Microenvironment-Sensitive Nanoparticles Targeting Hypoxic Regions Enhances the Chemotherapy Outcome of Lung Cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, H.; Fu, K.; Ji, Y.; Ji, W.; Li, Y.; Yan, Q.; Yang, G. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917-driven microrobots for effective tumor targeted drug delivery and tumor regression. Acta Biomater. 2023, 169, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Din, S.R.U.; Saeed, S.; Khan, S.U.; Arbi, F.M.; Xuefang, G.; Zhong, M. Bacteria-driven cancer therapy: Exploring advancements and challenges. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2023, 191, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghban, R.; Roshangar, L.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Seidi, K.; Ebrahimi-Kalan, A.; Jaymand, M.; Kolahian, S.; Javaheri, T.; Zare, P. Tumor microenvironment complexity and therapeutic implications at a glance. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Seidi, K.; Zarghami, N. Tumor vascular infarction: Prospects and challenges. Int. J. Hematol. 2017, 105, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Largeot, A.; Pagano, G.; Gonder, S.; Moussay, E.; Paggetti, J. The B-Side of Cancer Immunity: The Underrated Tune. Cells 2019, 8, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkwill, F.R.; Capasso, M.; Hagemann, T. The tumor microenvironment at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 5591–5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, B.; Jeong, W.I.; Tian, Z. Liver: An organ with predominant innate immunity. Hepatology 2008, 47, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oura, K.; Morishita, A.; Tani, J.; Masaki, T. Tumor Immune Microenvironment and Immunosuppressive Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, M.; Seki, E. The liver fibrosis niche: Novel insights into the interplay between fibrosis-composing mesenchymal cells, immune cells, endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 143, 111556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Yan, X.; Zhang, H. The tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential of traditional Chinese medicine. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Wang, F.; Xue, W.; Zhai, D.; Liu, J.; Lv, X. New insights into fibrotic signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1196298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seyhan, D.; Allaire, M.; Fu, Y.; Conti, F.; Wang, X.W.; Gao, B.; Lafdil, F. Immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: From pathogenesis to immunotherapy. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 1132–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, H.; Deng, Y.; Tai, Y.; Zeng, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce PDL1+ neutrophils through the IL6-STAT3 pathway that foster immune suppression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lan, X.; Li, W.; Zhao, K.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Zhao, H. Revisiting the role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1582532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mansoori, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Davudian, S.; Shirjang, S.; Baradaran, B. The Different Mechanisms of Cancer Drug Resistance: A Brief Review. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 7, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, J.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr.; Yuan, X.; Xiao, Y.; Li, H. Editorial: Cancer cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors affecting tumor immune evasion. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1261820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fatima, S. Tumor Microenvironment: A Complex Landscape of Cancer Development and Drug Resistance. Cureus 2025, 17, e82090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Druker, B.J.; Sawyers, C.L.; Kantarjian, H.; Resta, D.J.; Reese, S.F.; Ford, J.M.; Capdeville, R.; Talpaz, M. Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1038–1042, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croop, J.M.; Raymond, M.; Haber, D.; Devault, A.; Arceci, R.J.; Gros, P.; Housman, E.D. The three mouse multidrug resistance (mdr) genes are expressed in a tissue-specific manner in normal mouse tissues. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989, 9, 1346–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo-Sorbello, G.S.; Bertino, J.R. Current understanding of methotrexate pharmacology and efficacy in acute leukemias. Haematologica 2001, 86, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth, R.E.; Jansen, K. Turning the corner on therapeutic cancer vaccines. NPJ Vaccines 2019, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leko, V.; Rosenberg, S.A. Identifying and targeting human tumor antigens for t cell-based immunotherapy of solid tumors. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lybaert, L.; Lefever, S.; Fant, B.; Smits, E.; De Geest, B.; Breckpot, K.; Dirix, L.; Feldman, S.A.; van Criekinge, W.; Thielemans, K.; et al. Challenges in neoantigen-directed therapeutics. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, N.; Shen, G.; Gao, W.; Huang, Z.; Huang, C.; Fu, L. Neoantigens: Promising targets for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tran, N.H.; Qiao, R.; Xin, L.; Chen, X.; Shan, B.; Li, M. Personalized deep learning of individual immunopeptidomes to identify neoantigens for cancer vaccines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Buuren, M.M.; Calis, J.J.; Schumacher, T.N. High sensitivity of cancer exome-based CD8 T cell neo-antigen identification. Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e28836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thind, A.S.; Monga, I.; Thakur, P.K.; Kumari, P.; Dindhoria, K.; Krzak, M.; Ranson, M.; Ashford, B. Demystifying emerging bulk RNA-Seq applications: The application and utility of bioinformatic methodology. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbab259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.; Coukos, G.; Bassani-Sternberg, M. Identification of tumor antigens with immunopeptidomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richman, L.P.; Vonderheide, R.H.; Rech, A.J. Neoantigen Dissimilarity to the Self-Proteome Predicts Immunogenicity and Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cell Syst. 2019, 9, 375–382.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Schreiber, R.D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 2015, 348, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Shi, T.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J.; Song, Y.; Wei, J.; Ren, S.; Zhou, C. Tumor neoantigens: From basic research to clinical applications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chakraborty, C.; Majumder, A.; Bhattacharya, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Lee, S.S. The landscape of neoantigens and its clinical applications: From immunobiology to cancer vaccines. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2024, 7, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.W.; Jia, S.P.; Xing, S.J.; Ma, H.L.; Wang, X.; Tang, Q.Y.; Li, Z.W.; Wu, Q.; Bai, M.; Zhang, X.Y.; et al. Personalized neoantigen cancer vaccines: Current progression, challenges and a bright future. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, X.; You, J.; Hong, L.; Liu, W.; Guo, P.; Hao, X. Neoantigen cancer vaccines: A new star on the horizon. Cancer Biol. Med. 2023, 21, 274–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Capietto, A.H.; Hoshyar, R.; Delamarre, L. Sources of Cancer Neoantigens beyond Single-Nucleotide Variants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naffaa, M.M.; Al-Ewaidat, O.A.; Gogia, S.; Begiashvili, V. Neoantigen-based immunotherapy: Advancing precision medicine in cancer and glioblastoma treatment through discovery and innovation. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 2025, 6, 1002313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan, R.Y.; Chung, W.H.; Chu, M.T.; Chen, S.J.; Chen, H.C.; Zheng, L.; Hung, S.-I. Recent development and clinical application of cancer vaccine: Targeting neoantigens. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 4325874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti-Mays, M.E.; Redman, J.M.; Collins, J.M.; Bilusic, M. Cancer vaccines: Enhanced immunogenic modulation through therapeutic combinations. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017, 13, 2561–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreno, B.M.; Magrini, V.; Becker-Hapak, M.; Kaabinejadian, S.; Hundal, J.; Petti, A.A.; Ly, A.; Lie, W.-R.; Hildebrand, W.H.; Mardis, E.R.; et al. Cancer immunotherapy. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity of melanoma neoantigen-specific T cells. Science 2015, 348, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, E.; Robbins, P.F.; Lu, Y.C.; Prickett, T.D.; Gartner, J.J.; Jia, L.; Pasetto, A.; Zheng, Z.; Ray, S.; Groh, E.M.; et al. T-Cell transfer therapy targeting mutant KRAS in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Khatib, M.N.; R, R.; Kaur, M.; Srivastava, M.; Barwal, A.; Rajput, G.V.S.; Rajput, P.; Syed, R.; Sharma, G.; et al. Advancements and challenges in personalized neoantigen-based cancer vaccines. Oncol. Rev. 2025, 19, 1541326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Smith, P.L.; Piadel, K.; Dalgleish, A.G. Directing T-Cell Immune Responses for Cancer Vaccination and Immunotherapy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alard, E.; Butnariu, A.B.; Grillo, M.; Kirkham, C.; Zinovkin, D.A.; Newnham, L.; Macciochi, J.; Pranjol, M.Z.I. Advances in Anti-Cancer Immunotherapy: Car-T Cell, Checkpoint Inhibitors, Dendritic Cell Vaccines, and Oncolytic Viruses, and Emerging Cellular and Molecular Targets. Cancers 2020, 12, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pu, J.; Liu, T.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Fu, X.; Wan, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, B.; Sharma, A.; Lukacs-Kornek, V.; et al. T cells in cancer: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic advances. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, X.; Wei, Y.; Yu, Y.; Tian, X. Vaccine adjuvants: Mechanisms and platforms. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morgan, M.; Brittany, P.; Lipika, C. Erratum to A comparison of cancer vaccine adjuvants in clinical trials [Cancer Treatment and Research Communications Volume 34, 2023, 100667]. Cancer Treat Res. Commun. 2023, 36, 100733, Erratum in Cancer Treat Res. Commun. 2023, 34, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.G.; Orr, M.T.; Fox, C.B. Key roles of adjuvants in modern vaccines. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelle, E.C.; McEntee, C.P. Vaccine adjuvants: Tailoring innate recognition to send the right message. Immunity 2024, 57, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.C.; Park, J.H.; Prausnitz, M.R. Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 1547–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trimble, C.L.; Morrow, M.P.; Kraynyak, K.A.; Shen, X.; Dallas, M.; Yan, J.; Edwards, L.; Parker, R.L.; Denny, L.; Giffear, M.; et al. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 2078–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, S. Effect of vaccine administration modality on immunogenicity and efficacy. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 1509–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kuai, R.; Sun, X.; Yuan, W.; Xu, Y.; Schwendeman, A.; Moon, J.J. Subcutaneous Nanodisc Vaccination with Neoantigens for Combination Cancer Immunotherapy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharom, F.; Ramirez-Valdez, R.A.; Khalilnezhad, A.; Khalilnezhad, S.; Dillon, M.; Hermans, D.; Fussell, S.; Tobin, K.K.S.; Dutertre, C.A.; Lynn, G.M.; et al. Systemic vaccination induces CD8+ T cells and remodels the tumor microenvironment. Cell 2022, 185, 4317–4332.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizard, M.; Roussel, H.; Diniz, M.O.; Karaki, S.; Tran, T.; Voron, T.; Dransart, E.; Sandoval, F.; Riquet, M.; Rance, B.; et al. Induction of resident memory T cells enhances the efficacy of cancer vaccine. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Edwards, J.; Wilmott, J.S.; Madore, J.; Gide, T.N.; Quek, C.; Tasker, A.; Ferguson, A.; Chen, J.; Hewavisenti, R.; Hersey, P.; et al. CD103(+) tumor-resident CD8(+) T cells are associated with improved survival in immunotherapy-naïve melanoma patients and expand significantly during anti-PD-1 treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 3036–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oltmanns, F.; Vieira Antão, A.; Irrgang, P.; Viherlehto, V.; Jörg, L.; Schmidt, A.; Wagner, J.T.; Rückert, M.; Flohr, A.S.; Geppert, C.I.; et al. Mucosal tumor vaccination delivering endogenous tumor antigens protects against pulmonary breast cancer metastases. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e008652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luo, G.F.; Chen, W.H.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, X.Z. Cell primitive-based biomimetic functional materials for enhanced cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 945–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolhassani, A.; Safaiyan, S.; Rafati, S. Improvement of different vaccine delivery systems for cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kisakov, D.N.; Belyakov, I.M.; Kisakova, L.A.; Yakovlev, V.A.; Tigeeva, E.V.; Karpenko, L.I. The use of electroporation to deliver DNA-based vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2023, 23, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, M.; Kumari, A.; Paul, B.; Varshney, A.; Saini, A.; Verma, C.; Mani, I. Challenges and opportunities of gene therapy in cancer. OBM Genet. 2024, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. Optimisation of Ultrasound-Mediated Delivery of MRNA to Mammalian Cells. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, V. Ultrasound mediated delivery of drugs and genes to solid tumors. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hosseinpour, S.; Walsh, L.J. Laser-assisted nucleic acid delivery: A systematic review. J. Biophotonics 2021, 14, e202000295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, J.H.; Oosterhuis, K.; Schumacher, T.N.; Haanen, J.B.; Bins, A.D. Intradermal vaccination by DNA tattooing. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1143, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nidetz, N.F.; McGee, M.C.; Tse, L.V.; Li, C.; Cong, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, W. Adeno-associated viral vector-mediated immune responses: Understanding barriers to gene delivery. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 207, 107453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, Y.; Guirnalda, P.D.; Wood, L.M. Listeria and Salmonella bacterial vectors of tumor-associated antigens for cancer immunotherapy. Semin Immunol. 2010, 22, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Liang, L.; Zhang, H. An Overview of Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Platforms for mRNA Vaccines for Treating Cancer. Vaccines 2024, 12, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paston, S.J.; Brentville, V.A.; Symonds, P.; Durrant, L.G. Cancer Vaccines, Adjuvants, and Delivery Systems. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 627932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oelkrug, C. Analysis of physical and biological delivery systems for DNA cancer vaccines and their translation to clinical development. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2024, 13, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Hoai, T.; Pezzutto, A.; Westermann, J. Gene Gun Her2/neu DNA Vaccination: Evaluation of Vaccine Efficacy in a Syngeneic Her2/neu Mouse Tumor Model. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1317, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, C.; Lin, C.T.; Hung, C.F.; Pai, S.; Juang, J.; He, L.; Gillison, M.; Pardoll, D.; Wu, L.; Wu, T.-C. Comparison of the CD8+ T cell responses and antitumor effects generated by DNA vaccine administered through gene gun, biojector, and syringe. Vaccine 2003, 21, 4036–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, G.; Yu, Z.; Jiang, C.; Xu, C. Ultrasound-assisted immunotherapy for malignant tumour. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1547594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, P.; Chen, J.; Zhong, R.; Xia, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yao, H. Recent advances of ultrasound-responsive nanosystems in tumour immunotherapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 198, 114246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Hong, H.; Won, M.; Rha, H.; Ding, Q.; Kang, N.; Kang, H.; Kim, J.S. Mechanical stimuli-driven cancer therapeutics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Roosinovich, E.; Ma, B.; Hung, C.F.; Wu, T.C. Therapeutic HPV DNA vaccines. Immunol. Res. 2010, 47, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashiwagi, S. Laser adjuvant for vaccination. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 3485–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pokorna, D.; Rubio, I.; Müller, M. DNA-vaccination via tattooing induces stronger humoral and cellular immune responses than intramuscular delivery supported by molecular adjuvants. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 2008, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aneed, A. An overview of current delivery systems in cancer gene therapy. J Control. Release 2004, 94, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.H. Designer adjuvants for enhancing the efficacy of infectious disease and cancer vaccines based on suppression of regulatory T cell induction. Immunol. Lett. 2009, 122, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conry, R.M.; Khazaeli, M.B.; Saleh, M.N.; Allen, O.K.; Barlow, D.L.; Moore, E.S.; Craig, D.; Arani, R.B.; Schlom, J.; LoBuglio, A.F. Phase I trial of a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding carcinoembryonic antigen in metastatic adenocarcinoma: Comparison of intradermal versus subcutaneous administration. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 2330–2337. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Liang, B.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Feng, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, T.; Yan, F.; Yang, S.; Xia, X. Viral vectored vaccines: Design, development, preventive and therapeutic applications in human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, Z.; Pei, L.; Chen, Y.; Ding, Z. Prospects and Challenges of Lung Cancer Vaccines. Vaccines 2025, 13, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, X.; Jin, X.; Zhao, Z.; Song, W.; Tan, Q.; Zhao, R.; Jia, W.; et al. Oncolytic virus VG161 in refractory hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature 2025, 641, 503–511, Erratum in Nature 2025, 641, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Rawding, P.; Bu, J.; Hong, S.; Hu, Q. Chemically and Biologically Engineered Bacteria-Based Delivery Systems for Emerging Diagnosis and Advanced Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2102580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, R.; Ruan, H.; Liu, C.; Fan, S.; Li, J. Bacteria and Bacterial Components as Natural Bio-Nanocarriers for Drug and Gene Delivery Systems in Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xie, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, W.; Ding, J. Bacterial Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy: “Why” and “How”. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghoubi, A.; Khazaei, M.; Jalili, S.; Hasanian, S.M.; Avan, A.; Soleimanpour, S.; Cho, W.C. Bacteria as a double-action sword in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2020, 1874, 188388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Min, J.J.; Tan, W.; Zheng, J.H. Targeted cancer immunotherapy with genetically engineered oncolytic Salmonella typhimurium. Cancer Lett. 2020, 469, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Lillard, J.W., Jr. Nanoparticle-based targeted drug delivery. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2009, 86, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, M.H.; Cha, G.S.; Jung, I.D.; Kang, T.H.; Han, H.D. Nanoparticle-based vaccine delivery for cancer immunotherapy. Immune Netw. 2013, 13, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Rheima, A.M.; Kadhim, M.M.; Ahmed, N.N.; Mohammed, S.H.; Abbas, F.H.; Abed, Z.T.; Mahdi, Z.M.; Abbas, Z.S.; Hachim, S.K.; et al. An overview of nanoparticles in drug delivery: Properties and applications. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 46, 233–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. Emerging role of exosomes in cancer therapy: Progress and challenges. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wu, C. Smart nanoparticle delivery of cancer vaccines enhances tumorimmune responses: A review. Front. Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 1564267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, Y.; Xing, S.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, J.; Cai, Y.; Ma, P.; Miao, H.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, N.; et al. Exosome-based anticancer vacc.ines: From bench to bedside. Cancer Lett. 2024, 595, 216989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, R.; Umeano, A.C.; Kou, Y.; Xu, J.; Farooqi, A.A. Nanoparticle systems for cancer vaccine. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Türeci, Ö.; Löwer, M.; Schrörs, B.; Lang, M.; Tadmor, A.; Sahin, U. Challenges towards the realization of individualized cancer vaccines. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, S.; Hou, Y.; Yang, J. Intranasal delivery of cationic liposome-protamine complex mRNA vaccine elicits effective anti-tumor immunity. Cell. Immunol. 2020, 354, 104143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.L.; Lin, H.J.; Wang, H.W.; Tsai, W.Y.; Lin, S.F.; Chien, M.Y.; Liang, P.-H.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Liu, D.-Z. Galactosylated liposome as a dendritic cell-targeted mucosal vaccine for inducing protective anti-tumor immunity. Acta Biomater. 2015, 11, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Kan, Y.; Fang, Y.; Gao, J.; Kong, X.; Wang, J. Nanomaterials-driven in situ vaccination: A novel frontier in tumor immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Miao, L.; Sui, J.; Hao, Y.; Huang, G. Nanoparticle cancer vaccines: Design considerations and recent advances. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 15, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Ahn, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, M.; Gujrati, V.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Shin, E.C.; Jon, S. Effects of gold nanoparticle-based vaccine size on lymph node delivery and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses. J. Control. Release 2017, 256, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliamonte, M.; Petrizzo, A.; Mauriello, A.; Tornesello, M.L.; Buonaguro, F.M.; Buonaguro, L. Potentiating cancer vaccine efficacy in liver cancer. OncoImmunology 2018, 7, e1488564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsari, M.; Dimopoulou, V.; Koskinas, J.; Armakolas, A. Immune System and Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): New Insights into HCC Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zarlashat, Y.; Ghaffar, A.; Guerra, F.; Picca, A. Immunological Landscape and Molecular Therapeutic Targets of the Tumor Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akunne, O.Z.; Anulugwo, O.E.; Azu, M.G. Emerging strategies in cancer immunotherapy: Expanding horizons and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Immuno Oncol. 2024, 9, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tojjari, A.; Saeed, A.; Singh, M.; Cavalcante, L.; Sahin, I.H.; Saeed, A. A Comprehensive Review on Cancer Vaccines and Vaccine Strategies in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Köhler, N.; Maringer, Y.; Bucher, P.; Bilich, T.; Zwick, M.; Dicks, S.; Nelde, A.; Dubbelaar, M.; Scheid, J.; et al. The oncogenic fusion protein DNAJB1-PRKACA can be specifically targeted by peptide-based immunotherapy in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizukoshi, E.; Nakamoto, Y.; Arai, K.; Yamashita, T.; Sakai, A.; Sakai, Y.; Kagaya, T.; Yamashita, T.; Honda, M.; Kaneko, S. Comparative analysis of various tumor-associated antigen-specific t-cell responses in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sera, T.; Hiasa, Y.; Mashiba, T.; Tokumoto, Y.; Hirooka, M.; Konishi, I.; Matsuura, B.; Michitaka, K.; Udaka, K.; Onji, M. wilms’ tumour 1 gene expression is increased in hepatocellular carcinoma and associated with poor prognosis. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berasain, C.; Herrero, J.I.; Garcia-Trevijano, E.R.; Avila, M.A.; Esteban, J.I.; Mato, J.M.; Prieto, J. Expression of Wilms’ tumor suppressor in the liver with cirrhosis: Relation to hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 and hepatocellular function. Hepatology 2003, 38, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Srinivasan, R.; Chawla, Y.; Sharma, S.; Chakraborti, A.; Rajwanshi, A. Telomerase activity, telomere length and human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression in hepatocellular carcinoma is independent of hepatitis virus status. Liver Int. 2009, 29, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, H.; Yokosuka, O.; Imazeki, F.; Saisho, H.; Omata, M. Telomerase activity and telomere length in hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology 1997, 11, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukoshi, E.; Nakamoto, Y.; Tsuji, H.; Yamashita, T.; Kaneko, S. Identification of alpha-fetoprotein-derived peptides recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HLA-A24+ patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.; Kim, H. Glypican-3: A new target for cancer immunotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Gao, R.L.; Adeyemo, O.; Itkin, M.; Kaplan, D.E. Expansion of interferon-gamma-producing multifunctional CD4+ T-cells and dysfunctional CD8+ T-cells by glypican-3 peptide library in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 139, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, O.L.; Chen, Y.T. Cancer/testis (CT) antigens: Potential targets for immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhan, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.T.; Sun, S.N.; Guo, X.K.; Yin, H.; Wei, Y.; Li, S.Y.; et al. Targeting Tumor-Associated Antigens in Hepatocellular Carcinoma for Immunotherapy: Past Pitfalls and Future Strategies. Hepatology 2021, 73, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, H.; Mizukoshi, E.; Kobayashi, E.; Tamai, T.; Hamana, H.; Ozawa, T.; Kishi, H.; Kitahara, M.; Yamashita, T.; Arai, K.; et al. Association Between High-Avidity T-Cell Receptors, Induced by α-Fetoprotein-Derived Peptides, and Anti-Tumor Effects in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1395–1406.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Nobuoka, D.; Shirakawa, H.; Kuronuma, T.; Motomura, Y.; Mizuno, S.; Ishii, H.; Nakachi, K.; Konishi, M.; et al. Phase I trial of a glypican-3-derived peptide vaccine for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Immunologic evidence and potential for improving overall survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3686–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, L.; Liu, H.; Song, W.; Liu, D.; Li, Z.; Pan, C.-X. Combination strategies to maximize the benefits of cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzzi, F.; Riccardo, F.; Conti, L.; Tarone, L.; Semprini, M.S.; Bolli, E.; Barutello, G.; Quaglino, E.; Lollini, P.L.; Cavallo, F. Cancer vaccines: Target antigens, vaccine platforms and preclinical models. Mol. Asp. Med. 2025, 101, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, L.H.; Ribas, A.; Meng, W.S.; Dissette, V.B.; Amarnani, S.; Vu, H.T.; Seja, E.; Todd, K.; Glaspy, J.A.; McBride, W.H.; et al. T-cell responses to HLA-A*0201 immunodominant peptides derived from alpha-fetoprotein in patients with hepatocellular cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 5902–5908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Löffler, M.W.; Gori, S.; Izzo, F.; Mayer-Mokler, A.; Ascierto, P.A.; Königsrainer, A.; Ma, Y.T.; Sangro, B.; Francque, S.; Vonghia, L.; et al. Phase I/II Multicenter Trial of a Novel Therapeutic Cancer Vaccine, HepaVac-101, for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 2555–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, L.H.; Ribas, A.; Dissette, V.B.; Lee, Y.; Yang, J.Q.; De la Rocha, P.; Duran, S.D.; Hernandez, J.; Seja, E.; Potter, D.M.; et al. A phase I/II trial testing immunization of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with dendritic cells pulsed with four alpha-fetoprotein peptides. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 2817–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarakanovskaya, M.G.; Chinburen, J.; Batchuluun, P.; Munkhzaya, C.; Purevsuren, G.; Dandii, D.; Hulan, T.; Oyungerel, D.; Kutsyna, G.A.; Reid, A.A.; et al. Open-label Phase II clinical trial in 75 patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving daily dose of tableted liver cancer vaccine, hepcortespenlisimut-L. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2017, 4, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, Q.; Li, Q. A pilot trial of personalized neoantigen pulsed autologous dendritic cell vaccine as adjuvant treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e16264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Ofuji, K.; Yoshimura, M.; Tsuchiya, N.; Takahashi, M.; Nobuoka, D.; Gotohda, N.; Takahashi, S.; Kato, Y.; et al. Phase II study of the GPC3-derived peptide vaccine as an adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1129483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greten, T.F.; Forner, A.; Korangy, F.; N’Kontchou, G.; Barget, N.; Ayuso, C.; Ormandy, L.A.; Manns, M.P.; Beaugrand, M.; Bruix, J. A phase II open label trial evaluating safety and efficacy of a telomerase peptide vaccination in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, C.S.; Lee, T.Y.; Chao, H.W. Targeting glypican-3 as a new frontier in liver cancer therapy. World J. Hepatol. 2025, 17, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Devan, A.R.; Nair, B.; Pradeep, G.K.; Alexander, R.; Vinod, B.S.; Nath, L.R.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. The role of glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Insights into diagnosis and therapeutic potential. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, T.; Kataoka, H. Glypican 3-Targeted Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Lin, B.; Li, M. The role of alpha-fetoprotein in the tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1363695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Q. Alpha-Fetoprotein and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunity. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 2018, 9049252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, H.; Jang, M.; Kim, E. Exploring the Multifunctional Role of Alpha-Fetoprotein in Cancer Progression: Implications for Targeted Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, M.; Mizukoshi, E.; Tamai, T.; Kitahara, M.; Yamashita, T.; Arai, K.; Terashima, T.; Iida, N.; Fushimi, K.; Kaneko, S. Immune response to human telomerase reverse transcriptase-derived helper T cell epitopes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tornesello, M.L.; Cerasuolo, A.; Starita, N.; Tornesello, A.L.; Bonelli, P.; Tuccillo, F.M.; Buonaguro, L.; Isaguliants, M.G.; Buonaguro, F.M. The Molecular Interplay between Human Oncoviruses and Telomerase in Cancer Development. Cancers 2022, 14, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mazny, A.; Sayed, M.; Sharaf, S. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase messenger RNA (TERT mRNA) as a tumour marker for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 15, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Mou, D.C.; Leng, X.S.; Peng, J.R.; Wang, W.X.; Huang, L.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.Y. Expression of cancer-testis antigens in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 2034–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Noordam, L.; Ge, Z.; Özturk, H.; Doukas, M.; Mancham, S.; Boor, P.P.C.; Campos Carrascosa, L.; Zhou, G.; van den Bosch, T.P.P.; Pan, Q.; et al. Expression of Cancer Testis Antigens in Tumor-Adjacent Normal Liver Is Associated with Post-Resection Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, L.Q.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.F.; Lv, Z.H.; Zhang, B.; Yang, J.Y. Expression of cancer-testis antigen (CTA) in tumor tissues and peripheral blood of Chinese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Nadda, N.; Quadri, A.; Kumar, R.; Paul, S.; Tanwar, P.; Gamanagatti, S.; Dash, N.R.; Saraya, A.; Nayak, B. Assessments of TP53 and CTNNB1 gene hotspot mutations in circulating tumour DNA of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1235260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Qiu, L.; Dong, X.; Chen, G.; Shi, Y.; Cai, L.; Liu, W.; Ye, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Personalized neoantigen vaccine combined with PD-1 blockade increases CD8+ tissue-resident memory T-cell infiltration in preclinical hepatocellular carcinoma models. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, T.L.; Li, C.L.; Gong, Y.Q.; Hou, F.T.; Chen, C.W. Identification of tumor antigens and immune subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma for mRNA vaccine development. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2023, 15, 1717–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, H.F.; Gao, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z.W. The mechanisms of renin-angiotensin system in hepatocellular carcinoma: From the perspective of liver fibrosis, HCC cell proliferation, metastasis and angiogenesis, and corresponding protection measures. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, Y. Promising new strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Res. 2017, 47, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, H. Molecularly targeted therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 80, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandlik, D.S.; Mandlik, S.K.; Choudhary, H.B. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: Current status and future perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 1054–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kleponis, J.; Skelton, R.; Zheng, L. Fueling the engine and releasing the break: Combinational therapy of cancer vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Biol. Med. 2015, 12, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Goswami, S.; Raychaudhuri, D.; Siddiqui, B.A.; Singh, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Liu, J.; Subudhi, S.K.; Poon, C.; Gant, K.L.; et al. Immune checkpoint therapy-current perspectives and future directions. Cell 2023, 186, 1652–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Chen, Y.; Cai, W.; Dong, S.; Zhao, J.; Chen, L.; Cheng, C.-S. Combination immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: Synergies among immune checkpoints, TKIs, and chemotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugiapaglia, S.; Spagnolo, F.; Intonti, S.; Novelli, F.; Curcio, C. Fighting Pancreatic Cancer with a Vaccine-Based Winning Combination: Hope or Reality? Cells 2024, 13, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akabane, M.; Imaoka, Y.; Lee, G.R.; Pawlik, T.M. Immunology, immunotherapy, and the tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: A comprehensive review. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2025, 21, 1403–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.zs.com/insights/cancer-vaccine-development-strategies#:~:text=Therapeutic%20cancer%20vaccines%20appear%20poised,perceptions%20of%20value%20and%20price (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Looi, K.S.; Nakayasu, E.S.; Diaz, R.A.; Tan, E.M.; Almeida, I.C.; Zhang, J.Y. Using proteomic approach to identify tumor-associated antigens as markers in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7, 4004–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Basmenj, E.R.; Pajhouh, S.R.; Ebrahimi Fallah, A.; Naijian, R.; Rahimi, E.; Atighy, H.; Ghiabi, S.; Ghiabi, S. Computational epitope-based vaccine design with bioinformatics approach; a review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yurina, V.; Adianingsih, O.R. Predicting epitopes for vaccine development using bioinformatics tools. Ther. Adv. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 10, 25151355221100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Allaire, M.; Da Fonseca, L.G.; Sanduzzi-Zamparelli, M.; Choi, W.M.; Monge, C.; Liu, K.; Leibfried, M.; Manes, S.; Maravic, Z.; Mishkovikj, M.; et al. Disparities in access to systemic therapies for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: An analysis from the International Liver Cancer Association. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2025, 57, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Repáraz, D.; Aparicio, B.; Llopiz, D.; Hervás-Stubbs, S.; Sarobe, P. Therapeutic Vaccines against Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Era: Time for Neoantigens? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joosten, S.A. Individual- and population-associated heterogeneity in vaccine-induced immune responses. The impact of inflammatory status and diabetic comorbidity. Semin. Immunol. 2025, 78, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaoka, K.; Hosoi, A.; Iino, T.; Morishita, Y.; Matsushita, H.; Kakimi, K. Dendritic cell vaccine induces antigen-specific CD8+ T cells that are metabolically distinct from those of peptide vaccine and is well-combined with PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Oncoimmunology 2017, 7, e1395124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sangro, B.; Sarobe, P.; Hervás-Stubbs, S.; Melero, I. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, J.; Zheng, B.; Goswami, S.; Meng, L.; Zhang, D.; Cao, C.; Li, T.; Zhu, F.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. PD1Hi CD8+ T cells correlate with exhausted signature and poor clinical outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggeletopoulou, I.; Pantzios, S.; Triantos, C. Personalized Immunity: Neoantigen-Based Vaccines Revolutionizing Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treatment. Cancers 2025, 17, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachostergios, P.J. Cancer vaccines: Advances, hurdles, and future directions. Explor. Target Antitumor Ther. 2025, 6, 1002350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayyaz, A.; Haqqi, A.; Khan, R.; Irfan, M.; Khan, K.; Reiner, Ž.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Calina, D. Revolutionizing cancer treatment: The rise of personalized immunotherapies. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, F.; Gairing, S.J.; Ilyas, S.I.; Galle, P.R. Emerging immunotherapy for HCC: A guide for hepatologists. Hepatology 2022, 75, 1604–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greten, T.F.; Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Cheng, A.L.; Duffy, A.G.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Finn, R.S.; Galle, P.R.; Goyal, L.; He, A.R.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusnick, J.; Bruneau, A.; Tacke, F.; Hammerich, L. Ferroptosis in Cancer Immunotherapy—Implications for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Immuno 2022, 2, 185–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, Q.; Zhou, G.-M.; Wang, W.-J.; Shi, P.-P.; Wang, Z.-H. Potential biomarkers for the prognosis and treatment of HCC immunotherapy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 2027–2046. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Lim, J.M.; Yu, B.; Song, S.; Neeli, P.; Sobhani, N.K.P.; Bonam, S.R.; Kurapati, R.; Zheng, J.; Chai, D. The next-generation DNA vaccine platforms and delivery systems: Advances, challenges and prospects. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1332939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Wang, J.F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Molina, J.R. Comparative Analysis of Predictive Biomarkers for PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors in Cancers: Developments and Challenges. Cancers 2022, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Xue, W.; Zhang, M. Predictive biomarkers for PD-1 and PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Immunotherapy 2019, 11, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonaguro, L.; HEPAVAC Consortium. Developments in cancer vaccines for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Cancer Type | Target Antigen | Study Plan | Preclinical/Clinical Phase | Outcome Measures | Trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Personalized polypeptide DNA | 4 mg vaccine at Day 1, 29 (±/1–7 days), and Day 57 (±7 days) with interval least 21 days interval between each dose, Intramuscular | 1 | Safety and Immunogenicity of personalized polyepitope DNA vaccine strategy | NCT02348320 |

| Breast cancer | Mammaglobin-A antigen | 4 mg vaccine on days 28, 56, and 84), intramuscular, Via TriGrid electroporation system | 1 | Safety, immune response, progression-free survival, overall survival, objective tumor response rate | NCT02204098 |

| Melanoma | Mouse TYRP2 DNA | Intramuscularly at four escalating doses (500, 2000, 4000 or 8000 μg) at three-week intervals for six immunizations. | 1 | Safety and feasibility and any antitumor response generated after immunizations. | NCT00680589 |

| Melanoma | gp75 DNA vaccine | 1 mL, 2 mL or 4 mL every 3 weeks across 5 sessions | 1 | Safety and feasibility of intramuscular vaccination in patients with stage III or IV melanoma. | NCT00034554 |

| Prostate cancer | Rhesus Prostate Specific Antigen (rhPSA) | Patients divided into 4 cohorts receiving 50 µg, 150 µg, 400 µg, or 1000 µg DNA/dose, administered intradermally with electroporation assistance | 1 and 2 | Feasibility and safety of escalating doses | NCT00859729 |

| Non-Small cell Lung cancer | Semi-allogeneic human fibroblasts transfected with genomic tumor DNA | 4 consecutive weekly injections, intradermally using a 1 mL syringe fitted with a 25-gauge needle. | 1 | Safety and feasibility, immune responses to the autologous tumor | NCT00793208 |

| Liver cancer | Alpha fetoprotein (AFP) DNA and sargramostim (GM-CSF) plasmid DNA | Administrated intramuscularly on days 1, 30, and 60, followed by a booster dose on day 90 comprising AFP adenoviral vector via both intramuscular and intradermal routes. | 1, 2 | Safety and immunogenicity, overall survival | NCT00093548 |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Glypican-3 (GPC3) | DNA plasmid vaccine (NWRD06) administered by electroporation; dose escalation cohorts: 1 mg, 4 mg, 8 mg | 1 | Safety and immunogenicity | NCT06088459 |

| Chronic Hepatitis Hepatitis C Infection Hepatocellular Carcinoma | INO-8000 (HCV antigen DNA) alone or co-administered with INO-9012 (interleukin [IL]-12 adjuvant DNA) | INO-8000 (HCV antigen DNA) alone or co-administered with INO-9012 (interleukin [IL]-12 adjuvant DNA) | 1 | Safety; HCV-specific CD4+/CD8+ T-cell responses | NCT02772003 |

| Renal cancer | Human prostate-specific membrane antigen DNA vaccine, mouse prostate-specific membrane antigen DNA | 6 intramuscular doses; alternating between mouse PSMA and human PSMA DNA vaccines in a sequential set of 3 dose each. | 1 | Safety and feasibility of vaccination, maximum tolerated dose, assess antitumor response | NCT00096629 |

| Head and neck cancer | pNGVL-4a-CRT/E7 (detox) DNA | Intramuscular, 3 Doses (0.5, 1, 2, or 4 mg) using a TDS-IM device on days 1, 22, and 43 with 200 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide intravenously one day prior to each vaccination. | 1 | To evaluate adverse event associated with vaccine and immune response | NCT01493154 |

| Glioblastoma | Neoantigen DNA | Vaccine once every 28 days for up to 6 doses, alongside Retifanlimab (500 mg every 28 days for up to 12 months), via electroporation-mediated intramuscular route | 1 | Safety, survival, overall survival, objective response rate | NCT05743595 |

| Oral cancer | Dendritic Cells w/Tumor DNA | 1 × 107 DCs per dose injected intranodally or perinodally into lymph nodes distant from head and neck region | 1 | Safety and feasibility of immunization, immunological responses to the vaccine and/or antitumor immune responses | NCT00377247 |

| Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia | GX-188E | 1 mg or 4 mg of GX-188E per dose, at 0, 4 and 12 weeks intramuscularly using electroporation device. | 2 | Safety, tolerability, and finding the optimal dose of the vaccine | NCT02139267 |

| Ovarian cancer | pUMVC3-hIGFBP-2 multi-epitope plasmid DNA | pUMVC3-hIGFBP-2 multi-epitope plasmid DNA vaccine intradermally once a month for 3 consecutive months. | 1 | Safety, immunogenicity, Disease-free survival, overall survival | NCT01322802 |

| Cancer Type | Antigen | Study Design | Phase | Outcome Measures | Trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Dendritic Cells Transfected with Survivin, hTERT and p53 mRNA | Combination of DC-based immunization with cyclophosphamide administration. | 1 | Toxicity, clinical tumor response, duration of tumor and immuno-response | NCT00978913 |

| Melanoma | mRNA-nanoparticle (mRNA-NP) | 3 intravenous doses of mRNA-NP vaccine (1 every 2 weeks), using 3 + 3 dose escalation design. mRNA dose range 0.00125–0.01 mg/kg. | 1 | Maximum tolerated dose, feasibility of treatment, overall response rate | NCT05264974 |

| Prostate cancer | Dendritic Cells Loaded With mRNA from primary prostate cancer tissue | Intradermal vaccination with mRNA-loaded Dendritic Cells derived from patient tumor. | 1 and 2 | Time to treatment failure, safety and toxicity of vaccination. Evaluation of immunological response. | NCT01197625 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | Personalized MRNA Neoantigen | Vaccine given with adebrelimab as adjuvant therapy. | 1 | Safety, ability, immunogenicity, and preliminary efficacy | NCT06735508 |

| Liver cancer | PD-1 mRNA LNP | Weekly doses (50–100 μg) for consecutive doses followed by a booster dose after 1 month. | 1 and 2 | Objective response rate, disease control rate, durable response rate, duration of response, response time | NCT07053072 |

| Various tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma | Patient-specific tumor neoantigens (NCI-4650) | Intramuscular injections every 2 weeks for up to 4 doses (with option of second course ~4 weeks later). | 1 and 2 | Safety, immunogenicity (neoantigen-specific T-cell responses) | NCT03480152 |

| HBV-positive Hepatocellular Carcinoma (waiting for liver transplantation) | HBV mRNA vaccine (HBV antigens) | Multiple mRNA vaccine doses (4 doses) during transplant waiting period. | 1 | Safety (AEs, DLTs), immunogenicity (antigen-specific T-cells), ORR, DCR, 1-year survival | NCT07077356 |

| Advanced/metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma (after standard therapy failure) | PD-1 mRNA-LNP vaccine (PD-1 as immunogen) | Weekly injections × 4, then 5th dose after 1 month; dose escalation (low/med/high). | 1 and 2 | Safety, tolerability, immunogenicity, preliminary efficacy | NCT07053072 |

| Advanced HBV-positive Hepatocellular Carcinoma (after failure of standard therapy) | HBV-mRNA vaccine | IM injections—dose escalation starting at 20 µg: weekly × 4 doses; 5th dose after one month. | 1 | Adverse events, objective response rate, progress-free survival, overall survival | NCT05738447 |

| Advanced/relapsed/refractory Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | mRNA-based personalized (neoantigen) vaccine—ABOR2014 (IPM511) | Intramuscular injection; 3 + 3 dose-escalation, two cycles (four injections per cycle). | Early phase | Safety, tolerability, immunokinetics/immunogenicity, preliminary efficacy | NCT05981066 |

| Head and neck cancer | BNT113 | Vaccine administrated in combination with pembrolizumab as adjuvant therapy. | 2 and 3 | Analysis of treatment-emergent adverse events, overall survival, progression-free survival | NCT04534205 |

| Glioblastoma | Brain tumor stem cells mRNA-loaded dendritic cells | Escalating intradermal dose (2 × 106–2 × 107 DCs), given weekly for 3 doses, then monthly. | 1 | Humoral and cellular immune responses | NCT00890032 |

| Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Cervical Cancer | NWRD09 | NWRD09 administered by intramuscular injection. | NA | Assessment of immunogenicity, histopathological improvement, HPV viral clearance, objective response rate, progression-free survival, duration of response, disease control rate | NCT07092007 |

| Ovarian cancer | 8 W_ova1 | Immunization with W_ova1 vaccine containing 3 ovarian cancer TAA RNA-LPX products. | 1 | Identification of patients exhibiting new or enhanced systemic immune responses to at any three vaccine antigens | NCT04163094 |