Mapping the Functional Epitopes of Human Growth Hormone: Integrating Structural and Evolutionary Data with Clinical Variants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence Alignments

2.2. Evolutionary Conservation of Amino Acids

2.3. Protein Structure Loop Modeling

2.4. HGH-Receptor Interaction Analysis

2.5. Disease-Causing Mutations

2.6. Prediction of Protein Stability upon Mutation Using Site-Directed Mutagenesis Tool (SDM)

2.7. Analysis of HGH Allele Frequencies from Genome Sequencing

3. Results

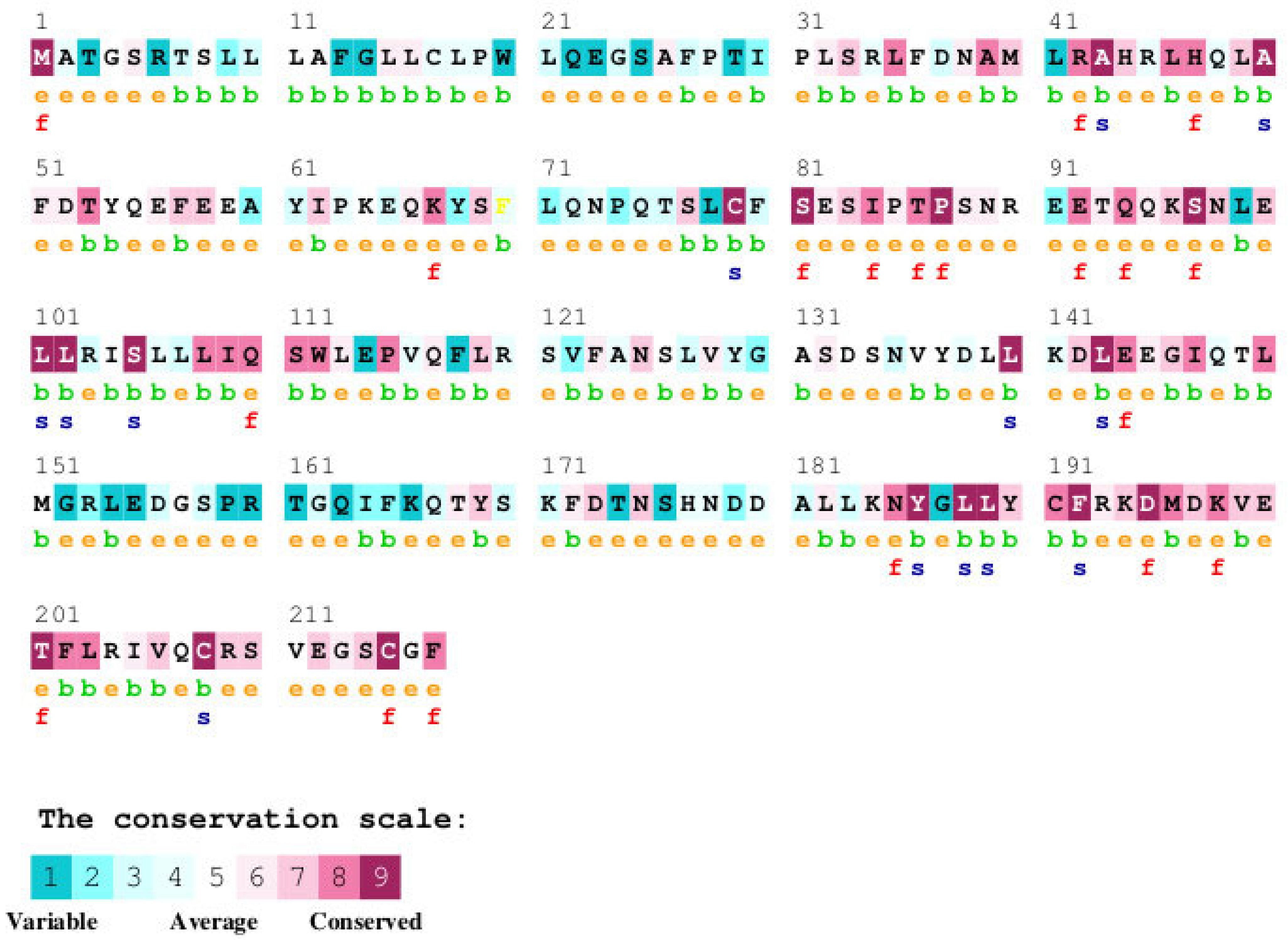

3.1. Analysis of GH Sequence Across Species

3.1.1. Analysis of Human GH Mutations and Their Locations in GH Protein

3.1.2. Comparison of Human GH Protein Sequence with Diverse GH Homologues Across Species

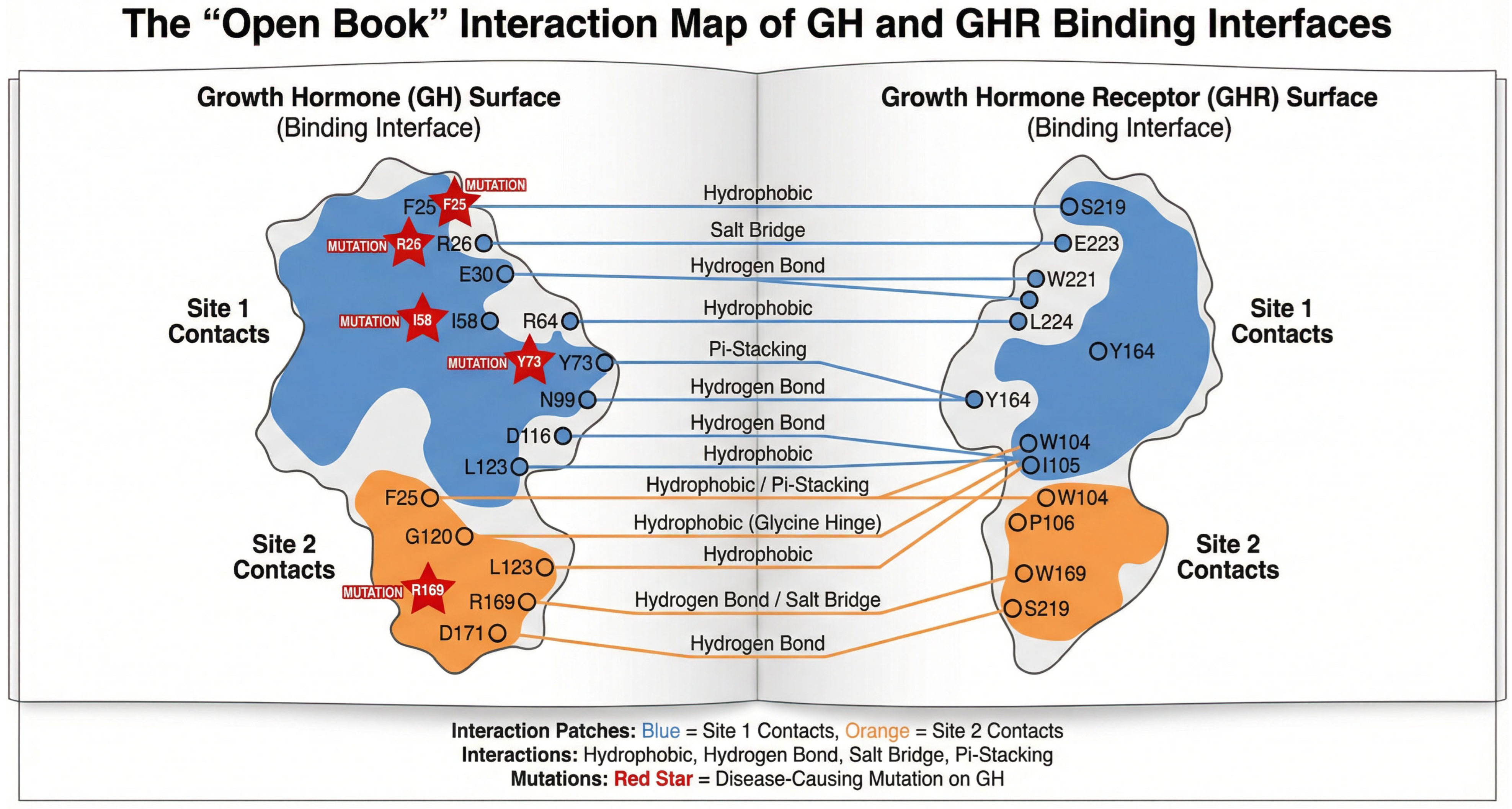

3.2. Analysis of GH-GHR Contacts

3.2.1. Structural Architecture of the High-Affinity Interface (Site 1)

3.2.2. The Dimerization Interface (Site 2) and Signaling Activation

3.2.3. Cross-Talk and Overlapping Residues

3.3. Analysis of Sequence Conservation Pattern in Growth Hormone at GH-GHR Contact Points

3.4. Stability Analysis of GH Mutations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GH | Growth hormone |

| GHR | Growth hormone receptor |

| GHD | Growth hormone deficiency |

| GHBP | Growth hormone binding protein |

References

- Rojas Velazquez, M.N.; Noebauer, M.; Pandey, A.V. Loss of Protein Stability and Function Caused by P228L Variation in NADPH-Cytochrome P450 Reductase Linked to Lower Testosterone Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, M.J.; Singh, S.; Ligabue-Braun, R.; Meneghetti, B.V.; Rispoli, T.; Kopacek, C.; Monteiro, K.; Zaha, A.; Rossetti, M.L.R.; Pandey, A.V. Characterization of Mutations Causing CYP21A2 Deficiency in Brazilian and Portuguese Populations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; Rojas Velazquez, M.N.; Udhane, S.S.; Kagawa, N.; Pandey, A.V. Variability in Loss of Multiple Enzyme Activities Due to the Human Genetic Variation P284T Located in the Flexible Hinge Region of NADPH Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; DiNardo, G.; Baj, F.; Zhang, C.; Gilardi, G.; Pandey, A.V. Differential effects of variations in human P450 oxidoreductase on the aromatase activity of CYP19A1 polymorphisms R264C and R264H. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 196, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; Fernandez-Cancio, M.; Benito-Sanz, S.; Camats, N.; Rojas Velazquez, M.N.; Lopez-Siguero, J.P.; Udhane, S.S.; Kagawa, N.; Fluck, C.E.; Audi, L.; et al. Molecular Basis of CYP19A1 Deficiency in a 46,XX Patient With R550W Mutation in POR: Expanding the PORD Phenotype. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatzoglou, K.S.; Webb, E.A.; Le Tissier, P.; Dattani, M.T. Isolated growth hormone deficiency (GHD) in childhood and adolescence: Recent advances. Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 376–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.V. Bioinformatics tools and databases for the study of human growth hormone. Endocr. Dev. 2012, 23, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Procter, A.M.; Phillips, J.A., 3rd; Cooper, D.N. The molecular genetics of growth hormone deficiency. Hum. Genet. 1998, 103, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, H.; Kimelman, J.; Birnbaum, M.J.; Chen, E.Y.; Seeburg, P.H.; Eberhardt, N.L.; Barta, A. The human growth hormone gene locus: Structure, evolution, and allelic variations. DNA 1987, 6, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis, P.E. Genetic control of growth. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2005, 152, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.A., 3rd; Cogan, J.D. Genetic basis of endocrine disease. 6. Molecular basis of familial human growth hormone deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1994, 78, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- de Vos, A.M.; Ultsch, M.; Kossiakoff, A.A. Human growth hormone and extracellular domain of its receptor: Crystal structure of the complex. Science 1992, 255, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluet-Pajot, M.T.; Epelbaum, J.; Gourdji, D.; Hammond, C.; Kordon, C. Hypothalamic and hypophyseal regulation of growth hormone secretion. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1998, 18, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, M.; Hosoda, H.; Date, Y.; Nakazato, M.; Matsuo, H.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 1999, 402, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis, P.E.; Deladoey, J.; Dannies, P.S. Molecular and cellular basis of isolated dominant-negative growth hormone deficiency, IGHD type II: Insights on the secretory pathway of peptide hormones. Horm. Res. 2002, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovic, V.; Miletta, M.C.; Eble, A.; Iliev, D.I.; Binder, G.; Fluck, C.E.; Mullis, P.E. Effect of zinc binding residues in growth hormone (GH) and altered intracellular zinc content on regulated GH secretion. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 4215–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrelund, H. The metabolic role of growth hormone in humans with particular reference to fasting. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2005, 15, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, U.J.; Ho, K.K. Modulation of growth hormone action by sex steroids. Clin. Endocrinol. 2006, 65, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauter, E.; Latta, F.; Nedeltcheva, A.; Spiegel, K.; Leproult, R.; Vandenbril, C.; Weiss, R.; Mockel, J.; Legros, J.J.; Copinschi, G. Reciprocal interactions between the GH axis and sleep. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2004, 14, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widdowson, W.M.; Healy, M.L.; Sonksen, P.H.; Gibney, J. The physiology of growth hormone and sport. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2009, 19, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walenkamp, M.J.; Wit, J.M. Genetic disorders in the GH IGF-I axis in mouse and man. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 157 (Suppl. 1), S15–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.G.; Mortensen, D.L.; Carlsson, L.M.; Spencer, S.A.; McKay, P.; Mulkerrin, M.; Moore, J.; Cunningham, B.C. Recombinant human growth hormone (GH)-binding protein enhances the growth-promoting activity of human GH in the rat. Endocrinology 1996, 137, 4308–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.W.; Spencer, S.A.; Cachianes, G.; Hammonds, R.G.; Collins, C.; Henzel, W.J.; Barnard, R.; Waters, M.J.; Wood, W.I. Growth hormone receptor and serum binding protein: Purification, cloning and expression. Nature 1987, 330, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niall, H.D. Revised primary structure for human growth hormone. Nat. New Biol. 1971, 230, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, M.L.; Faria, A.C.; Vance, M.L.; Johnson, M.L.; Thorner, M.O.; Veldhuis, J.D. Temporal structure of in vivo growth hormone secretory events in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1991, 260 Pt 1, E101–E110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.J.; Adams, J.J.; Pelekanos, R.A.; Wan, Y.; McKinstry, W.J.; Palethorpe, K.; Seeber, R.M.; Monks, T.A.; Eidne, K.A.; Parker, M.W.; et al. Model for growth hormone receptor activation based on subunit rotation within a receptor dimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gent, J.; Van Den Eijnden, M.; Van Kerkhof, P.; Strous, G.J. Dimerization and signal transduction of the growth hormone receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, J.; Carter-Su, C. Signaling pathways activated by the growth hormone receptor. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 12, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesover, A.D.; Dattani, M.T. Evaluation of growth hormone stimulation testing in children. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 84, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbone, M.; Dattani, M.T. Progression from isolated growth hormone deficiency to combined pituitary hormone deficiency. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2017, 37, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.G.; Dattani, M.T.; Clayton, P.E. Controversies in the diagnosis and management of growth hormone deficiency in childhood and adolescence. Arch. Dis. Child. 2016, 101, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovic, V.; Godi, M.; Pandey, A.V.; Lochmatter, D.; Buchanan, C.R.; Dattani, M.T.; Eblé, A.; Flück, C.E.; Mullis, P.E. Growth hormone (GH) deficiency type II: A novel GH-1 gene mutation (GH-R178H) affecting secretion and action. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovic, V.; Eblé, A.; Pandey, A.V.; Betta, M.; Mella, P.; Flück, C.E.; Buzi, F.; Mullis, P.E. A novel GH-1 gene mutation (GH-P59L) causes partial GH deficiency type II combined with bioinactive GH syndrome. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2011, 21, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovic, V.; Miletta, M.C.; Boot, A.M.; Losekoot, M.; Flück, C.E.; Pandey, A.V.; Eblé, A.; Wit, J.M.; Mullis, P.E. Short stature in two siblings heterozygous for a novel bioinactive GH mutant (GH-P59S) suggesting that the mutant also affects secretion of the wild-type GH. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 168, K35–K43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miletta, M.C.; Eblé, A.; Janner, M.; Parween, S.; Pandey, A.V.; Flück, C.E.; Mullis, P.E. IGHD II: A Novel GH-1 Gene Mutation (GH-L76P) Severely Affects GH Folding, Stability, and Secretion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E1575–E1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, E.A.; Dattani, M.T. Diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency. Endocr. Dev. 2010, 18, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Franca, M.M.; Jorge, A.A.; Alatzoglou, K.S.; Carvalho, L.R.; Mendonca, B.B.; Audi, L.; Carrascosa, A.; Dattani, M.T.; Arnhold, I.J. Absence of GH-releasing hormone (GHRH) mutations in selected patients with isolated GH deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, E1457–E1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatzoglou, K.S.; Kular, D.; Dattani, M.T. Autosomal Dominant Growth Hormone Deficiency (Type II). Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 2015, 12, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Madden, T.L.; Schaffer, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miller, W.; Lipman, D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazy, H.; Erez, E.; Martz, E.; Pupko, T.; Ben-Tal, N. ConSurf 2010: Calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38 (Suppl. 2), W529–W533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, E.; Darden, T.; Nabuurs, S.B.; Finkelstein, A.; Vriend, G. Making optimal use of empirical energy functions: Force-field parameterization in crystal space. Proteins 2004, 57, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrane, M. UniProt Knowledgebase: A hub of integrated protein data. Database 2011, 2011, bar009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worth, C.L.; Preissner, R.; Blundell, T.L. SDM—A server for predicting effects of mutations on protein stability and malfunction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (Suppl. 2), W215–W222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandurangan, A.P.; Ochoa-Montano, B.; Ascher, D.B.; Blundell, T.L. SDM: A server for predicting effects of mutations on protein stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W229–W235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topham, C.M.; Srinivasan, N.; Blundell, T.L. Prediction of the stability of protein mutants based on structural environment-dependent amino acid substitution and propensity tables. Protein Eng. 1997, 10, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reumers, J.; Schymkowitz, J.; Rousseau, F. Using structural bioinformatics to investigate the impact of non synonymous SNPs and disease mutations: Scope and limitations. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10 (Suppl. 8), S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Weisburd, B.; Thomas, B.; Solomonson, M.; Ruderfer, D.M.; Kavanagh, D.; Hamamsy, T.; Lek, M.; Samocha, K.E.; Cummings, B.B.; et al. The ExAC browser: Displaying reference data information from over 60 000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D840–D845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; Abecasis, G.R. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, D.S.; Lewis, M.D.; Horan, M.; Newsway, V.; Easter, T.E.; Gregory, J.W.; Fryklund, L.; Norin, M.; Crowne, E.C.; Davies, S.J.; et al. Novel mutations of the growth hormone 1 (GH1) gene disclosed by modulation of the clinical selection criteria for individuals with short stature. Hum. Mutat. 2003, 21, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, I.; Cogan, J.D.; Prince, M.A.; Kamijo, T.; Ogawa, M.; Phillips, J.A. Detection of Growth Hormone Gene Defects by Dideoxy Fingerprinting (ddF). Endocr. J. 1997, 44, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deladoey, J.; Stocker, P.; Mullis, P.E. Autosomal dominant GH deficiency due to an Arg183His GH-1 gene mutation: Clinical and molecular evidence of impaired regulated GH secretion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 3941–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Kaji, H.; Okimura, Y.; Goji, K.; Abe, H.; Chihara, K. Brief report: Short stature caused by a mutant growth hormone. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovic, V.; Besson, A.; Thevis, M.; Lochmatter, D.; Eble, A.; Fluck, C.E.; Mullis, P.E. Evaluation of the biological activity of a growth hormone (GH) mutant (R77C) and its impact on GH responsiveness and stature. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 2893–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Shirono, H.; Arisaka, O.; Takahashi, K.; Yagi, T.; Koga, J.; Kaji, H.; Okimura, Y.; Abe, H.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Biologically inactive growth hormone caused by an amino acid substitution. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Velazquez, M.N.; Therkelsen, S.; Pandey, A.V. Exploring Novel Variants of the Cytochrome P450 Reductase Gene (POR) from the Genome Aggregation Database by Integrating Bioinformatic Tools and Functional Assays. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, M.J.; Ligabue-Braun, R.; Zaha, A.; Rossetti, M.L.R.; Pandey, A.V. Variant predictions in congenital adrenal hyperplasia caused by mutations in CYP21A2. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 931089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organism | NCBI Seq ID | Uniprot Seq. ID | Uniprot Seq. Name | Seq Length | Seq Identity % | Seq Similarity % | Signal Pep |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | NP_000506 | P01241 | SOMA_HUMAN | 217 | 100 | 100 | 26 |

| Rhesus macaque | NP_001036203 | P33093 | SOMA_MACMU | 217 | 96 | 97 | 26 |

| Rat | NP_001030020 | P01244 | SOMA_RAT | 216 | 65 | 76 | 26 |

| Mouse | NP_032143 | P06880 | SOMA_MOUSE | 216 | 67 | 77 | 26 |

| Horse | NP_001075417 | P01245 | SOMA_HORSE | 216 | 67 | 79 | 26 |

| Pig | NP_999034 | P01248 | SOMA_PIG | 216 | 68 | 78 | 26 |

| Bovine | NP_851339 | P01246 | SOMA_BOVIN | 217 | 67 | 77 | 26 |

| Sheep | NP_001009315 | P67930 | SOMA_SHEEP | 217 | 67 | 76 | 26 |

| Guinea pig | NP_001166330 | Q9JKM4 | SOMA_CAVPO | 216 | 65 | 77 | 26 |

| Common turkey | XP_010722827 | P22077 | SOMA_MELGA | 216 | 55 | 73 | 25 |

| Chicken | NP_989690 | P08998 | SOMA_CHICK | 214 | 57 | 74 | 25 |

| Common ostrich | BAA82959 | Q9PWG3 | SOMA_STRCA | 215 | 54 | 72 | 25 |

| Japanese eel | AAA48535 | P08899 | SOMA_ANGJA | 207 | 44 | 61 | 19 |

| Goldfish | AAC19389 | O93359 | SOMA1_CARAU | 210 | 38 | 58 | 22 |

| Atlantic salmon | AAU11454 | Q5SDS1 | Q5SDS1_SALSA | 208 | 36 | 52 | 22 |

| Growth Hormone Deficiency, Isolated, 1B (IGHD1B) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Variant | Sequence Position | PDB No. | Effect of Mutation | dbSNP | Publication |

| L → P | 16 | - | suppresses secretion | [49] Millar | |

| D → N | 37 | 11 | - | [49] Millar | |

| R → C | 42 | 16 | reduced secretion | rs71640273 | [49] Millar |

| T → I | 53 | 27 | reduced ability to activate the JAK/STAT pathway | [49] Millar | |

| K → R | 67 | 41 | reduced ability to activate the JAK/STAT pathway | [49] Millar | |

| N → D | 73 | 47 | reduced ability to activate the JAK/STAT pathway | rs71640276 | [49] Millar |

| S → F | 97 | 71 | reduced ability to activate the JAK/STAT pathway | [49] Millar | |

| E → K | 100 | 74 | - | [49] Millar | |

| Q → L | 117 | 91 | reduced secretion | Q → R | [49] Millar |

| S → C | 134 | 108 | [49] Millar | ||

| S → R | 134 | 108 | reduced ability to activate the JAK/STAT pathway | [49] Millar | |

| T → A | 201 | 175 | reduced ability to activate the JAK/STAT pathway | [49] Millar | |

| Growth hormone deficiency, isolated, 2 (IGHD2) | |||||

| R → H | 209 | 183 | rs137853223 | [50] Miyata [51] Deladoey | |

| Kowarski syndrome (KWKS) | |||||

| R → C | 103 | 77 | No effect on GHR signaling pathway; does not affect interaction with GHR; results in a stronger interaction with GHBP; does not affect the subcellular location. | rs137853220 | [52] Takahashi [53] Petkovic |

| D → G | 138 | 112 | Loss of activity | rs137853221 | [54] Takahashi |

| Clinical Significance | Protein Residue | AA Pos | Ref Prot Res | PDB Res | ConSurf Conservation | Contact R 1 | Contact R 2 | UniProt Disease Variant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gln [Q] | 28 | Pro [P] | 2 | e | Yes (2) | |||

| Thr [T] | 30 | Ile [I] | 4 | b | Yes (4) | |||

| Lys [K] | 34 | Arg [R] | 8 | e | Yes (8) | |||

| His [H] | 38 | Asn [N] | 12 | e | Yes (12) | |||

| Phe [F] | 41 | Leu [L] | 15 | b | Yes (15) | |||

| His [H] | 42 | Arg [R] | 16 | e, f | Yes (16) | Yes (R>C) | ||

| Thr [T] | 43 | Ala [A] | 17 | b, s | ||||

| Arg [R] | 44 | His [H] | 18 | e | Yes (18) | |||

| Tyr [Y] | 47 | His [H] | 21 | e, f | Yes (21) | |||

| Thr [T] | 50 | Ala [A] | 24 | b, s | ||||

| B | Tyr [Y] | 51 | Phe [F] | 25 | e | Yes (25) | ||

| Pro [P] | 71 | Leu [L] | 45 | e | Yes (45) | |||

| Lys [K] | 73 | Asn [N] | 47 | e | Yes (N>D) | |||

| Thr [T] | 74 | Pro [P] | 48 | e | Yes (48) | |||

| P | Ser [S] | 79 | Cys [C] | 53 | b, s | |||

| Cys [C] | 88 | Ser [S] | 62 | e | Yes (62) | |||

| Lys [K] | 89 | Asn [N] | 63 | e | Yes (63) | |||

| His [H] | 103 | Arg [R] | 77 | e | Yes (R>C) | |||

| P | Cys [C] | 103 | 77 | |||||

| Cys [C] | 105 | Ser [S] | 79 | b, s | ||||

| Glu [E] | 110 | Gln [Q] | 84 | e, f | ||||

| Arg [R] | 117 | Gln [Q] | 91 | e | Yes (Q>L) | |||

| P | Gly [G] | 138 | Asp [D] | 112 | e | Yes (D>G) | ||

| Glu [E] | 142 | Asp [D] | 116 | e | Yes (116) | |||

| Asp [D] | 145 | Glu [E] | 119 | e | Yes (119) | |||

| Ser [S] | 146 | Gly [G] | 120 | b | Yes (120) | |||

| Met [M] | 149 | Thr [T] | 123 | b | Yes (123) | |||

| Pro [P] | 188 | Leu [L] | 162 | b, s | ||||

| His [H] | 190 | Tyr [Y] | 164 | b | Yes (164) | |||

| Glu [E] | 195 | Asp [D] | 169 | e, f | ||||

| Asn [N] | 198 | Lys [K] | 172 | e, f | Yes (172) | |||

| Lys [K] | 200 | Glu [E] | 174 | e | Yes (174) | |||

| Met [M] | 205 | Ile [I] | 179 | b | Yes (179) | |||

| Arg [R] | 208 | Cys [C] | 182 | b, s | Yes (182) | |||

| P | His [H] | 209 | Arg [R] | 183 | e | Yes (R>H) | ||

| Tyr [Y] | 215 | Cys [C] | 189 | e, f | Yes (189) | |||

| Ser [S] | 216 | Gly [G] | 190 | e | Yes (190) |

| SNV | Conservation Score | Residue Variety Across Species |

| P2Q | 8 | P,Y,V |

| I4T | 5 | A,F,T,P,E,V,M,I,L |

| R8K | 4 | S,W,N,K,E,H,Q,D,R,G |

| N12H | 7 | S,T,N,K,E,H,M,C,I,R,L |

| L15F | 1 | S,F,T,N,K,E,V,H,Q,M,R,I,G,L |

| R16H, R16L, R16C | 7 | H,Q,R,Y,L,V |

| A17T | 8 | S,A,T,I,L,V |

| H18R | 7 | S,W,T,N,E,H,Q,D |

| H21Y | 7 | F,S,H,K,R,Y,V |

| A24T | 8 | S,A,T,N,Y,V |

| F25Y, F25I | 6 | S,A,F,T,K,E,Y,Q,M,D,R,I,G,L |

| L45P | 6 | L |

| N47K, N47D | 3 | S,A,T,N,P,K,V,H,M,D,I,G |

| C53S, C53F | 9 | C |

| S62C | 5 | A,S,T,N,K,E,V,H,Q,M,I,G |

| N63K | 7 | S,D,N,P,G,E |

| R77H, R77C | 5 | S,N,K,H,Q,D,R,G,L |

| S79C | 7 | A,S,M,T,I,G,V |

| Q84F | 6 | S,W,P,Y,E,V,H,Q,M,D,R,I,L |

| Q91R | 3 | S,F,A,N,K,E,Y,V,H,Q,D,R,I,G,L |

| D112G, G112H | 1 | A,S,T,N,K,P,E,H,Q,D,R,G,L |

| D116E, D116N | 4 | A,S,N,K,E,Y,V,Q,D,R,I,G |

| E119D | 4 | S,A,T,N,K,E,V,Q,M,D,R,L |

| G120S, G120C | 9 | A,F,T,G,Y |

| T123M | 2 | S,A,T,N,K,E,V,M,R,I,L |

| L162P | 7 | F,T,M,N,K,I,L,V |

| Y164H | 6 | A,S,T,N,Y,H,M,C,R |

| D169E | 9 | D,E |

| K172N | 9 | H,M,N,R,K |

| E174K | 9 | S,Q,D,Y,E |

| I179V, I179M, I179S | 7 | F,T,M,I,L,V |

| C182R | 9 | C |

| R183H, R183C | 9 | Q,K,R |

| C189Y | 9 | C |

| G190S | 4 | S,A,T,G |

| Mutation | WT_SSE | WT_RSA (%) | WT_DEPTH ( Å ) | WT_OSP | WT_SS | WT_SN | WT_SO | MT_SSE | MT_RSA (%) | MT_DEPTH ( Å ) | MT_OSP | MT_SS | MT_SN | MT_SO | Predicted ΔΔG | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2Q | p | 89 | 3.2 | 0.11 | - | - | - | p | 99 | 3.3 | 0.08 | - | - | - | −0.8 | - |

| I4T | b | 55.1 | 3.5 | 0.33 | - | - | - | b | 70.7 | 3.4 | 0.26 | - | - | - | −1.09 | - |

| I4V | b | 55.1 | 3.5 | 0.33 | - | - | - | b | 55.1 | 3.3 | 0.33 | - | - | - | −0.07 | - |

| R8K | H | 59.6 | 3.4 | 0.31 | + | - | - | H | 66.7 | 3.5 | 0.27 | - | - | - | −0.43 | - |

| N12H | H | 57.8 | 3.5 | 0.33 | + | - | + | H | 58.6 | 3.5 | 0.26 | + | - | - | 0.68 | + |

| L15F | H | 74.6 | 3.2 | 0.23 | - | - | - | H | 79.7 | 3.3 | 0.19 | - | - | - | −0.63 | - |

| R16H | H | 44.2 | 3.8 | 0.34 | + | - | - | H | 31.9 | 3.9 | 0.4 | + | - | + | 0.19 | + |

| R16L | H | 44.2 | 3.8 | 0.34 | + | - | - | H | 20.9 | 4.1 | 0.44 | - | - | - | 0.39 | + |

| R16C | H | 44.2 | 3.8 | 0.34 | + | - | - | H | 22.1 | 4.2 | 0.44 | + | - | + | −0.76 | - |

| A17T | H | 1.4 | 6.7 | 0.54 | - | - | - | H | 0.3 | 6.9 | 0.59 | - | + | - | −1.88 | - |

| H18R | H | 69.2 | 3.4 | 0.26 | + | - | - | H | 70.1 | 3.4 | 0.2 | - | - | - | 0.06 | + |

| H21Y | H | 18.8 | 4.3 | 0.47 | - | - | - | H | 25.8 | 4.5 | 0.41 | - | - | - | 0.65 | + |

| A24T | H | 0 | 8.3 | 0.57 | - | - | - | H | 0 | 8.4 | 0.65 | - | - | + | −3.21 | - |

| F25Y | H | 57.4 | 3.6 | 0.27 | - | - | - | H | 57.6 | 3.6 | 0.27 | - | - | - | 0.47 | + |

| F25I | H | 57.4 | 3.6 | 0.27 | - | - | - | H | 47.8 | 3.6 | 0.34 | - | - | - | 0.31 | + |

| L45P | H | 40.9 | 3.6 | 0.33 | - | - | - | H | 34 | 3.7 | 0.33 | - | - | - | −2.23 | - |

| P48T | H | 78 | 3.1 | 0.2 | - | - | - | H | 95 | 3.2 | 0.16 | - | - | - | 0.34 | + |

| C53S | b | 3.7 | 5.9 | 0.43 | + | - | + | b | 4.5 | 5.8 | 0.42 | + | - | - | −1.11 | - |

| N47K | b | 62.6 | 3.3 | 0.39 | + | + | + | b | 82.8 | 3.3 | 0.2 | - | - | - | −0.32 | - |

| N47D | b | 62.6 | 3.3 | 0.39 | + | + | + | b | 67.5 | 3.3 | 0.33 | - | - | + | −0.44 | - |

| C53F | b | 3.7 | 5.9 | 0.43 | + | - | + | b | 3.6 | 5.2 | 0.51 | - | - | - | −0.62 | - |

| S62C | a | 84.6 | 3.1 | 0.14 | + | - | - | a | 90.8 | 3.2 | 0.11 | - | - | - | 0.62 | + |

| N63K | b | 71.2 | 3.5 | 0.3 | + | + | - | b | 83.5 | 3.3 | 0.16 | - | - | - | −0.18 | - |

| R77H | H | 19.4 | 4.9 | 0.45 | - | - | + | H | 17 | 4.7 | 0.54 | + | - | + | −0.07 | - |

| R77C | H | 19.4 | 4.9 | 0.45 | - | - | + | H | 12.1 | 5 | 0.57 | - | - | + | −0.71 | - |

| S79C | H | 0 | 10.9 | 0.57 | - | - | + | H | 0 | 10.8 | 0.61 | - | + | + | 1.52 | + |

| Q84E | H | 21.4 | 4 | 0.43 | + | - | - | H | 12.1 | 4.4 | 0.45 | + | - | - | 0.4 | + |

| Q91R | H | 64.4 | 3.4 | 0.24 | - | - | - | H | 78.7 | 3.4 | 0.16 | - | - | - | −0.15 | - |

| Q91K | H | 64.4 | 3.4 | 0.24 | - | - | - | H | 57.2 | 3.4 | 0.21 | - | - | - | −0.44 | - |

| Q91L | H | 64.4 | 3.4 | 0.24 | - | - | - | H | 62.9 | 3.4 | 0.23 | - | - | - | 0.29 | + |

| D112G | H | 78.3 | 3.4 | 0.27 | - | - | + | H | 82.6 | 3.7 | 0.34 | - | - | - | −0.16 | - |

| D112H | H | 78.3 | 3.4 | 0.27 | - | - | + | H | 76.7 | 3.4 | 0.25 | - | - | + | 0.88 | + |

| D116E | H | 54.7 | 3.6 | 0.31 | + | - | - | H | 57.1 | 3.8 | 0.26 | - | - | - | 1.25 | + |

| D116N | H | 54.7 | 3.6 | 0.31 | + | - | - | H | 61.9 | 3.7 | 0.29 | + | - | - | −0.35 | - |

| E119D | H | 85.5 | 3.3 | 0.2 | - | - | - | H | 80.4 | 3.3 | 0.25 | - | - | - | −1.48 | - |

| G120S | H | 64.2 | 4.6 | 0.46 | - | - | - | H | 30.8 | 4.2 | 0.42 | - | - | + | 0.18 | + |

| G120C | H | 64.2 | 4.6 | 0.46 | - | - | - | H | 30.1 | 4.2 | 0.4 | - | - | + | 0.7 | + |

| T123M | H | 47.5 | 3.8 | 0.29 | - | - | + | H | 52.2 | 3.6 | 0.24 | - | - | - | 1.19 | + |

| L162P | H | 3.5 | 6 | 0.48 | - | - | - | H | 16.4 | 5.4 | 0.39 | - | - | - | −4.31 | - |

| Y164H | H | 13.3 | 5.2 | 0.48 | - | - | - | H | 10.8 | 4.9 | 0.48 | - | - | - | −1.27 | - |

| D169E | H | 1.4 | 7.7 | 0.53 | + | - | + | H | 3 | 9.3 | 0.6 | + | - | + | −0.01 | - |

| K172N | H | 27.5 | 3.9 | 0.4 | - | - | - | H | 35 | 4.3 | 0.42 | - | - | + | −0.69 | - |

| E174K | H | 24.3 | 3.7 | 0.4 | + | - | - | H | 32.8 | 4.2 | 0.33 | - | - | - | −1.01 | - |

| I179M | H | 23 | 4.2 | 0.4 | - | - | - | H | 32.8 | 4.1 | 0.32 | + | - | - | −0.02 | - |

| I179S | H | 23 | 4.2 | 0.4 | - | - | - | H | 19.5 | 4.5 | 0.39 | - | - | + | −0.8 | - |

| I179V | H | 23 | 4.2 | 0.4 | - | - | - | H | 20.4 | 4.3 | 0.43 | - | - | - | −0.35 | - |

| C182R | H | 28.7 | 3.5 | 0.4 | + | - | + | H | 68.5 | 3.6 | 0.21 | - | - | - | 1.04 | + |

| R183H | H | 31.8 | 3.7 | 0.3 | + | - | + | H | 77.5 | 3.4 | 0.16 | - | - | - | −1.1 | - |

| R183C | H | 31.8 | 3.7 | 0.3 | + | - | + | H | 72.9 | 3.2 | 0.2 | - | - | - | −0.65 | - |

| C189Y | a | 22.9 | 3.9 | 0.29 | + | - | - | a | 75.2 | 3.4 | 0.11 | - | - | - | 0.78 | + |

| G190S | b | 199.3 | 3.5 | 0.07 | - | - | - | p | 107.2 | 3.1 | 0.08 | - | - | - | 0 | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verma, S.; Pandey, A.V. Mapping the Functional Epitopes of Human Growth Hormone: Integrating Structural and Evolutionary Data with Clinical Variants. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121012

Verma S, Pandey AV. Mapping the Functional Epitopes of Human Growth Hormone: Integrating Structural and Evolutionary Data with Clinical Variants. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121012

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerma, Sonia, and Amit V. Pandey. 2025. "Mapping the Functional Epitopes of Human Growth Hormone: Integrating Structural and Evolutionary Data with Clinical Variants" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121012

APA StyleVerma, S., & Pandey, A. V. (2025). Mapping the Functional Epitopes of Human Growth Hormone: Integrating Structural and Evolutionary Data with Clinical Variants. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121012