Abstract

Unethical behavior of employees threatens business development and sustainability by damaging the image and reputation of companies. Unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB) must also be considered in this context, and its antecedents should be analyzed. This study aims to advance what is known about how leader-member exchange (LMX) and organizational identification affect employees’ intentions to perform UPB, by incorporating the effect of leadership communication. Within this context, the mediating role of organizational identification and the moderating role of leader’s message framing (gain or loss) are examined. The research sample consists of 306 employees working for state and private banks operating in Turkey. Participants were divided into two groups and message framing was manipulated with a hypothetical story using vignettes. Research hypotheses were tested by structural equation modeling (SEM) and multi-group analysis. Results confirmed positive effects of LMX and organizational identification on UPB. Organizational identification also mediated the effect of LMX on UPB. Moreover, leader’s communication style moderated the effects of LMX and organizational identification on UPB. When leaders used loss framing instead of gain framing, the effect of LMX on UPB was augmented whilst the effect of organizational identification diminished. Our study contributes to the literature by documenting how a leader’s communication style can trigger a shift towards UPB among highly identified employees. Research and managerial implications of the findings are discussed.

1. Introduction

Ethically questionable actions, unfortunately, have become a common phenomenon in corporate life which threatens business sustainability. While some of these actions are uncovered and turned into sensational corporate scandals (i.e., WelssFargo, Facebook, Uber, Volkswagen and Enron), some remain hidden within the organization. Unethical behavior is typically defined as any action “illegal or morally unacceptable to the wider society” [1] and can occur at any level within the organization, from entry-level employees to CEOs. When unethical behavior is disclosed, it not only causes legal problems for companies, but also seriously damages corporate image and reputation. Therefore, unethical employee behavior has been a key topic in management and organizational research for a long time. Ethical business conduct is also a critical concern for business sustainability. Today, business ethics has become one of the integral components of sustainable management and companies develop institutionalized processes to prevent ethical issues and ensure responsible development.

Employees generally act unethically for their own benefit, to retaliate against the company or to harm others [2,3]. However, sometimes, they may engage in unethical behavior aimed at serving the interests of others including the organization [4,5] or their leaders [6,7]. Such unethical behaviors carried out to benefit the organization are called unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB) [5]. Employees occasionally engage in UPB to protect or promote organizational interests in an environment of fierce competition [5,8,9]. However, as evidenced by the recent Volkswagen incident, in which employees rigged emission tests to help the company’s survival, UPB may damage external stakeholders, and once revealed, it can have severe consequences for the company’s reputation. Moral deviations can harm the interests of various stakeholders and the reputation of the company, thereby impairing the sustainable development of organizations. Although UPB is aimed to benefit the company in the short run, it damages the reputation of the organization in the long run and therefore contradicts the idea of sustainable development. Therefore, examining the causes and consequences of UPB is an important research topic in the field of sustainable business.

Several individual, organizational, and leadership factors have been identified as determinants of UPB in earlier studies (comprehensive reviews were provided by [10,11]. Although several studies have examined organizational identification [4,5,8,9,12,13,14] and leader-member exchange (LMX) [6,15,16] as significant drivers of UPB, little is known on the interactive effects of LMX and organizational identification on UPB. Particularly in small workgroups, members’ identification with the organization and their interaction with the leader can together create unusual results. In addition, with the exception of [17] and [18], the literature is almost silent on the effects of leadership communication on followers’ UPB intentions. Consequently, we have an incomplete picture of the factors motivating employees to engage in UPB, and completing this picture can be instructive both theoretically and practically.

Against this background, the main purpose of this research is to find out the independent and joint effects of LMX and organizational identification on UPB. A second important issue to address is whether leadership communication plays a role in the relationships between LMX, identification and UPB. For example, when announcing a critical situation, does the leader’s message framing (i.e., gain vs. loss) have an impact on followers’ UPB intentions? If so, how will this effect be reflected in the LMX-identification-UPB interaction? To answer these questions, we hypothesize that the effects of LMX and organizational identification are moderated by the leader’s message framing. More specifically, the study aimed to achieve the following research objectives:

- ▪

- To examine independent and joint effects of LMX and organizational identification on UPB.

- ▪

- To determine the mediating role of organizational identification on the relationship between LMX and UPB.

- ▪

- To identify the moderating role of leader’s message framing.

To reach the research objectives, we conducted a field study on working adults. The research is delimited to the retail banking industry, where several ethical problems are frequently encountered [19]. In general, the banking industry features a destructive competition which is reflected in the behavior of employees. In particular, recent digital transformation in the retail banking sector in Turkey has rapidly changed business models and banks have downsized physically. In this context, the reduction in the number of branches and the dismissal of employees caused intense competition among the branches within the banks. Thus, it is worth examining the eventual UPB and its antecedents in the Turkish banking sector. Moreover, the shrinking branch size and the transformation of branches into small teams require more careful examination of the consequences of organizational identification and LMX in these units.

This study’s findings will provide more insight about the interactions between unethical pro-organizational behavior, LMX and organizational identification. Furthermore, the study will demonstrate how a leader’s message framing influences employees’ willingness to engage in UPB, bridging the gap between management communication and the UPB literature. Finally, findings of the study will give managers a better awareness of the role of management communication in employees’ responses to major challenges, and provide them with critical insights to communicate more effectively with employees in such situations.

We organized the paper in three sections. In the first section, we begin by reviewing the literature on UPB, LMX, and organizational identification; discuss the possible interactions between them and develop hypotheses. In the second section, we outline our sample and research methodology, analyze data and present the findings. In the last section, we discuss our findings and present several implications. Finally, we address study limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior

Counter-productive employee behavior and workplace deviance are among the major topics of organizational psychology and business ethics domains [2,20,21]. Numerous studies have been conducted on the causes and effects of unethical behavior that harm the organization (misusing company resources, lying, theft, abusing, sabotage, violating company policies etc.) or other members (bullying, harassment, abusing, violence) [22,23]. However, employees occasionally engage in ethically questionable behavior in order to protect or benefit the organization [24]. “Actions that are intended to promote the effective functioning of the organization or its members (e.g., leaders) and violate core societal values, morals, laws, or standards of proper conduct” are termed as “unethical pro-organizational behavior” [5] and are receiving increasing attention from scholars [11].

Despite the fact that they are not overtly listed in job descriptions or sought by supervisors, UPBs are intended to benefit the organization [5]. For a clear understanding of UPB, [4] identified three situations that fall outside of its scope: unethical behavior of an employee (a) without a specific intention to benefit or harm (b) aiming to benefit the organization but do not match the ultimate goal, and (c) conducted for the individual’s own benefit. From this perspective; for an unethical behavior to be within the scope of UPB, it must be undertaken deliberately, benefit the organization, and intend to defend the interests of the entire organization. The main feature that distinguishes UPB from other counterproductive or deviant workplace behavior is that it is unethical but intended to be “pro-organizational” [20]. UPB can take several forms, including concealing product faults, destroying incriminating information and documents, lying or misrepresenting the facts about the company’s products to customers. UPBs are morally problematic and potentially harmful to customers and stakeholders, despite the fact that they are voluntary extra role behavior conducted with an unselfish purpose [6]. When disclosed, actions that harm the interests of external stakeholders can damage the organization’s image and reputation. Thus, it is important to determine what drives employees to engage in UPB and to take necessary measures to prevent this.

Mostly drawn from social exchange theory [25,26], reciprocal social exchange mechanisms were argued to play a crucial role in motivating employees to engage in UPB [4,5,6,8,27]. When there is a strong desire to maintain a long-term employment relationship with the organization or to avoid the negative consequences of failing to meet the organization’s requirements, employees may move away from moral boundaries and regulations and become involved in UPB [28,29]. Further, in an environment of high unemployment, employees may undertake UPB to keep their jobs. Similarly, employees at risk of exclusion may turn to UPB to reduce this risk by demonstrating that they can contribute effectively to their workgroup [28]. Employees may also behave in ways that sustain or increase the good self-image of being associated with the employing organization, according to social identity theory [30]. UPB, from this perspective, is driven by sentiments of identity, commitment, dedication to the organization, and the quality of exchange with leaders [13]. For this reason, the effects of LMX and organizational identification on UPB have been extensively studied.

2.2. The Effect of Leader-Member Exchange

LMX is concerned with the quality of interaction, relationship and communication in the supervisor–subordinate dyad [31,32,33], and suggests that leaders don’t use the same style in dealing with all subordinates, but rather develop a different type of relationship or exchange with each of them [34]. It is heavily reliant on the leaders and followers developing mutual respect, confidence, loyalty, and a sense of obligation [35]. Owing to resource constraints, the leader develops a close relationship (high quality LMX) with only a few key subordinates, while relying mainly on formal authority, rules, and policies to ensure adequate performance (low quality LMX) with the rest of the work group [31]. Employees with a high quality LMX (in-group) get more support and guidance from the leader and obtain salient organizational resources compared to those with a low quality LMX (outgroup) [33]. Based on the social exchange theory [25,36], several studies indicated that high-quality LMX interactions produce beneficial organizational outcomes such as improved performance, satisfaction, decreased turnover and extra role behavior [37,38].

Because employees perceive their supervisors as agents representing the organization, quality of LMX is linked with employees’ organizational identity [39]. Leaders view employees with high-quality LMX as reliable assistants and assign them important roles and responsibilities along with the resources. In turn, employees with a high-quality LMX perceive their roles as better defined and stable in organizations and feel themselves to be members of the “in-group” [40]. As a result, employees with high-quality LMX feel to be privileged and valuable members of the organization and experience a stronger sense of unity with the organization. In contrast, employees with a low-quality LMX who receive less supervisory support, are deprived of resources and see fewer advancement opportunities, feel alienated and have a lower level of identification with the organization. It is, therefore, hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

LMX has a positive effect on organizational identification.

According to social exchange theory, LMX develops from interactions between the leader and the follower, and is motivated by the mutual benefits derived from these exchanges [25,26]. In this context, when the parties gain mutual benefit, the principle of reciprocity comes into play [36]. Given the principle of reciprocity, the employee not only fulfills their formal role, but also feels a responsibility to act for the leader’s benefit beyond the formal job description [6]. Employees with a high quality LMX tend to make sacrifices to protect or to benefit their leaders and are more likely to engage in extra role behavior [41]. In a similar vein, their tendency to exhibit UPB will also be high when they think it will benefit their leaders. Despite the fact that committing unethical action endangers an employee’s reputation and employment, employees with a high quality LMX may consider engaging in UPB as a personal sacrifice [6] and means to satisfy positive reciprocity motives [15]. It is, therefore, hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

LMX has a positive effect on the willingness to engage in UPB.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification

Social identity theory [30] suggests that individuals tend to categorize themselves and others into distinct social groups, and participation in one of these groups contributes to a person’s self-concept. Similarly, organizational identification is the degree to which an employee identifies with the same characteristics that he or she feels, that make up the employing organization, as well as the commitment and membership to the organization they work for [42]. Employees with a high level of organizational identification perceive the organization’s success and failure as their own [43]. As with a psychological bond that someone has with an organization on a social, emotional and cognitive level [44], identification creates a sense of unity between an individual and the organization [45]. Organizational identification means that the organization’s values and goals become embedded in the employee’s self-concept [46], and a person who strongly identifies with an organization behaves in the best interests of the organization [47].

Studies indicate that organizational identification brings many individual and organizational positive outcomes [44,47]. However, under fierce competition, employees with a strong sense of belonging to the company may fall into ethical dilemmas in order to protect the interests of the company. Employees with high levels of organizational identification may disregard some moral standards and conduct misbehavior in order to benefit the company. A growing body of empirical research has shown the collinearity between high organizational identification and UPB [4,9,13,23,27,48]. Positive reciprocity beliefs [5], reaffirming belongingness and membership to the organization (affiliative concerns) [49] or negative emotions stemmed from work stress and detachment [28] may motivate employees to engage in UPB. Moreover, those who work under intense stress may engage in a cognitive justification described as “neutralization”, which reduces the ethicality associated with unethical behaviors [4]. It is hypothesized, based on these arguments, that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Organizational identification has a positive effect on the willingness to engage in UPB.

Recent studies concluded that identification is a multi-foci construct, and identification with the organization, supervisor, and work group are related, but distinct phenomena [50]. In an organizational structure that emerges in small groups, organizational identification may rather occur in the form of identification with the work group. In this case, a strong organizational identification may drive employees to shift from an individual “I” perspective to a more “we” point of view in the reciprocal relationship with their workgroup. This shift can also contribute to employees’ intentions to go beyond moral boundaries in the workplace to protect the interests of their “in-group”, not just their leaders. In this case, employees with a high quality LMX may justify UPB as displaying loyalty or even altruism toward their in-group. From this point of view, LMX may pose an indirect effect on UPB through organizational identification. Taking into account the aforementioned arguments and findings of the recent studies [27,51], we posit that, LMX may indirectly influence employees’ intentions to engage in UPB through their identification with the organization. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Organizational identification mediates the relationship between LMX and UPB.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Message Framing

The content and delivery of the messages given by leaders significantly influence followers’ attitudes and behaviors [52,53,54]. Aside from the source and content of the message, the framing of the message is an essential aspect in determining how employees respond to organizational communication [55]. Message framing is a persuasion tactic that emphasizes either the bonuses and incentives of conforming to the message or the costs and penalties of not paying attention to it [56]. Framing can be used as a tool to influence employees’ message comprehension and to make up their mind, especially under uncertainty. The way information is presented has a significant impact on human judgment and decision-making [57]. Individuals may provide different responses to the same queries or make different decisions based on different styles of expression, although the meaning is still the same [58]. A particular form of the framing effect is identified as “goal framing” [59]. Goal framing stresses either positive outcomes of undertaking an action (gain framing) or negative outcomes of not undertaking that behavior (loss framing). People frequently make decisions based on how the predicted outcome is phrased, especially in high-risk scenarios [60]. Individuals’ emotions may be reflected in their decisions depending on how the prospective consequence of a decision is portrayed (as a gain or loss) [61].

Managerial messages are essential guides for employees to interpret which action is imperative for the organization’s survival. From this point of view, how managers frame a problem can affect employees’ evaluation and ethical decision making [62]. Managerial communications might unintentionally drive employees to engage in ethically problematic behavior, especially in cultures with a large power distance [29]. If employees perceive a potential threat for the future of the organization, they may tend to engage in morally unacceptable behaviors in order to protect the organization or the leader [17]. In a similar vein, under fierce competition, followers who receive a positively framed message from their leaders can be over-inspired to achieve organizational goals. Based on an experimental study with a student sample, [18] have shown that leader’s communication style is likely to influence the relationship between followers’ organizational identification and willingness to participate in UPB. Nevertheless, the way a leader frames a message may have varying effects on UPB depending on followers’ interactions with the leader, too.

The drive to protect the organization becomes particularly evident in loss situations when the organization is threatened [17]. When the leader uses a loss frame, employees with a high quality LMX may be more likely to engage in UPB since they perceive a threat to the organization. In this case, employees with a high quality LMX have a stronger motivation to protect the leader and the organization, in order to maintain their privileged position and in-group status within the organization.

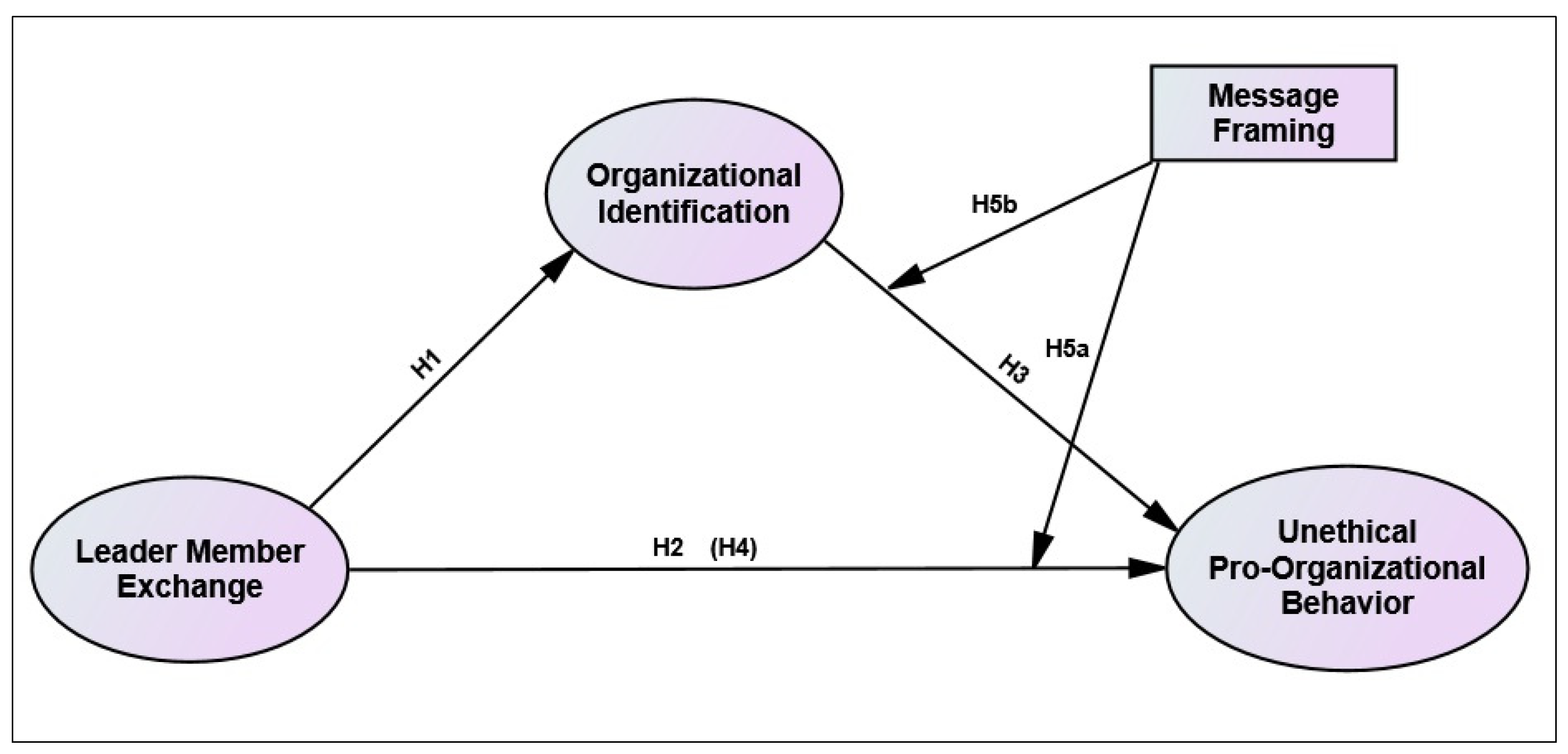

Employees with a high level of organizational identification may be more inclined to engage in UPB in order to achieve corporate goals because belonging to a successful organization will boost their self-esteem and improve their self-concept. To sum up, while the risk of losing something is more decisive in the case of high LMX, the desire to achieve organizational gains is more prominent in the case of high identification. In line with this reasoning, the following hypotheses are proposed. Figure 1 represents the proposed research model along with the hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Research Model.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Message framing moderates the effect of LMX on UPB, such that when the leader uses a loss frame, the positive effect of LMX on UPB will be stronger than when using a gain frame.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Message framing moderates the effect of organizational identification on UPB, such that when the leader uses a gain frame, the positive effect of organizational identification on UPB will be stronger than when using a loss frame.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context, Sample and Procedure

In order to test the hypotheses, we conducted a research on bank employees. Research data were collected from a convenient sample of 320 employees working at various branches of public and private banks operating in Turkey. We chose such a research sample, because the banking industry features a destructive competition which is reflected in the behavior of employees, and serious ethical issues are frequently observed [19,63]. The banking industry plays a leading role in the Turkish economy and makes a significant contribution to qualified employment. According to the Banks Association of Turkey, there are 49 banks operating in Turkey, having more than 9500 domestic branches and 200 K employees. Branches operate in small working groups of 20 people on average. They are the most important service channel where employees and the customers interact physically and are perceived as the face of the bank by customers. However, the recent digital transformation in the retail banking sector in Turkey has rapidly changed business models and employment policies [64]. As a result of the widespread use of online technologies such as digital banking, banks have downsized physically in order to minimize operational costs. In this context, the reduction in the number of branches and the dismissal of employees caused intense competition among the branches within the banks themselves [65]. Branch performance and profitability determine who will survive among the branches. Achieving the targets set by the headquarters is critical for the survival of branch managers and employees. This situation may drive bank employees to identify themselves with the branch they work for rather than the corporate identity of the bank, and to focus primarily on the branch goals and objectives as an immediate in-group. Thus, it is worth examining the level of identification of bank employees with their immediate work group (branch) and their exchange with the immediate supervisor (branch manager).

Respondents were reached through personal contacts and they were provided with the link of an online questionnaire. In order to ensure voluntary participation and honesty, a statement containing absolute anonymity and strict confidentiality commitment was made, and information that would lead to the identification of respondents (i.e., name, position) was not requested. Further, in order to reduce evaluation apprehension as a procedural remedy to social desirability bias, respondents were informed that there were no right or wrong answers and that they should answer questions honestly [66]. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of a Turkish University.

Study hypotheses were tested in a survey-based between subjects experiment. Excerpts depicting hypothetical scenarios (in vignettes) were used to manipulate message framing. Research data were collected using two versions of an online questionnaire with the same questions following two different stories. The online questionnaire consisted of four sections, beginning with the demographic questions. The second part consisted of LMX and organizational identification scales. After responding to the demographic questions, LMX and organizational identification scales; respondents were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions. They were instructed to “carefully read the excerpt which depicts a truly experienced event; imagine the manager in the scenario to be your real-life manager and the bank to be the organization in which you work in real life, and then answer the questions”. The vignette was about an incident that happened to a bank officer. Two versions of the vignette were developed by manipulating the way the branch manager explains (gain framing vs. loss framing) a particular issue (the importance of achieving sales targets for a new product) to employees (see Appendix A). The story was developed to reflect a real-life situation based on qualitative research with a small group of bank employees. Two alternative scenarios were created in consultation with experts (one university professor in the field of organizational behavior and a branch manager of a bank). Questions to capture participants’ intentions to engage in UPB, as well as manipulation check questions were added in the final section of the questionnaire.

3.2. Measures

Liden and Maslyn’s 11-item LMX scale [34] was used to assess leader-member exchange. The scale is originally proposed as a multidimensional construct with four dimensions (affect, loyalty, contribution and professional respect). A sample item from the scale is “I like my supervisor very much as a person”.

Mael and Ashforth’s 6-item unidimensional organizational identification scale [43] was used to capture identification. A sample item from the scale is “When someone criticized my organization, it feels like a personal insult”.

Respondents were asked to play the role of Mr(s)X and indicate how likely they were to engage in UPB (dependent variable) in order to attain sales targets. Unethical pro-organizational behavior was measured by the 6-item UPB scale developed by Umphress and others [5]. Sample items included “If it would help my organization, I would misrepresent the truth” and “If it would benefit my organization, I would withhold negative information about my company or its products from customers and clients”.

Respondents’ levels of agreement with six statements were measured to check the effectiveness of message framing manipulation. The statements were “The branch manager in the vignette used a (positive/negative) language; emphasized potential (gains/losses); highlighted possible (positive/negative) outcomes to explain the issue to the employees”. All measures relied on 5-point Likert type reflective scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We used translation (in Turkish) and back-translation (in English) procedures to maintain sematic equivalence of the scales. During the translation and back-translation process, we received support from a university professor who specializes in the organizational behavior field and another university lecturer who is an expert in the English language. Respondents’ age, education, gender, job tenure and organizational tenure (in years) were also measured as control variables.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Checks and Control Variables

Fourteen cases were excluded from the analysis due to inconsistent or missing responses, and as a result, 306 questionnaires were analyzed. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample. All of the respondents have some university degree, gender is almost evenly distributed, two thirds work in the private sector and forty percent work as office clerks. The average age of respondents is 35, with an average of 10.8 years of job tenure and 6.6 years of organizational tenure.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

One hundred and forty-six participants were randomly assigned to the gain-framing condition and one hundred and sixty to the loss-framing condition. Independent samples t-tests were used for manipulation checks. The mean score of the manipulation check statements in the “gain framing” group were 3.92 (sd. = 0.99) for gain statements and 2.10 (sd. = 0.88) for loss statements (t = 17.1 p < 0.001). In the “loss framing” group, mean scores were 1.99 (sd. = 1.01) and 3.79 (sd. = 1.03), respectively (t = −15.34 p < 0.001). These findings confirmed that the message framing manipulations worked properly.

A correlation analysis has been conducted to check the relations among the control variables (age, gender, job tenure and organizational tenure) and summated study variables (LMX, organizational identification, UPB). Table 2 shows descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables. None of the control variables had a statistically significant relationship with the study variables. Harman’s single-factor test was used to probe the common method bias [66]. Factor analysis revealed three factors explaining 80.5% of the variance. The largest factor accounted for 37% of the total variance. This finding suggested that common method bias is not likely to confound the results.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables.

4.2. Measurement Model and CFA

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to validate the measurement model using CB-SEM structural modeling methods. IBM SPSS Amos 24 was used to perform CFA and path analysis in order to test the study hypotheses. The estimation was completed on the basis of the maximum likelihood method. Finally, in order to test the proposed moderating effects, the intergroup differences were examined by multi-group analysis.

In the measurement model in which the LMX was treated with four correlated dimensions (affect, loyalty, contribution, and professional respect), LMX sub-dimensions had serious convergent and discriminant validity issues (square-roots of the AVE’s for all sub-dimensions were less than their correlations with other dimensions; HTMT criterion also indicated that the sub-dimensions were nearly indistinguishable from each other). Thus, we decided to use each of the four dimensions as indicators of a second order LMX construct, as suggested by [34] (p. 64).

In order to assess the validity and reliability of the revised measurement model, we conducted a CFA that included LMX, organizational identification and UPB constructs. We used item parcels as indicators for second-order LMX, reflecting the four sub-dimensions (affect, loyalty, contribution, and professional respect). For organizational identification and UPB, scale items were used as indicators. Fit statistics showed a good fit to the data: χ2 = 396.165, df = 215; CMIN/DF: 1.84; GFI: 0.902; TLI: 0.974; CFI: 0.978; RMSEA: 0.052. Scale items obtained high standardized factor loadings (between 0.832 and 0.924); and reliability statistics (Table 3).

Table 3.

Constructs’ factor loadings and reliability.

Table 4 shows the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of the correlations among study constructs, composite reliability (CR) for internal consistency, average variance extracted (AVE) for convergent validity, maximum shared variance (MSV) along with the correlation matrix of latent variables for discriminant validity. HTMT results indicate no issues regarding discriminant validity according to HTMT85 criterion [67]. All of the constructs had CR values greater than 0.7, indicating that they are reliable [68]. Strong standardized factor loadings (ranging between 0.83 and 0.92) of indicators to respective constructs and AVE values that are higher than the 0.5 threshold show convergent validity was also attained (Table 3). All MSV values are less than AVEs and the square root of AVEs are greater than inter-construct correlations, confirming no concerns about discriminant validity [69]. These findings clearly indicate that the measurement model with three reflective constructs established convergent and discriminant validity and reliability.

Table 4.

Validity and reliability indicators.

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Tests

Before testing the specific hypotheses, overall fit of the structural model was examined. The overall fit indexes of the structural model were satisfactory: χ2 = 396.165, df = 215; CMIN/DF: 1.843; GFI: 0.902; TLI: 0.974; CFI: 0.978; RMSEA: 0.053. Next, we tested direct and indirect causal relationships between the structures. Table 5 shows path coefficients and corresponding significance levels, 95% bias corrected confidence intervals and coefficients of determination.

Table 5.

Direct, indirect and total effects (mediated model).

Based on a bootstrap test with 5000 re-samples [70], we found that LMX exerted significantly positive direct effects on organizational identification (β = 0.676, p < 0.001) and UPB (β = 0.443; p < 0.001). These findings provided support for H1 and H2.

Consistent with H3; organizational identification exerted a significantly positive effect on UPB (β = 0.323; p < 0.001). Further, organizational identification was found to mediate the relationship between LMX and UPB. Path analysis revealed a statistically significant indirect effect of LMX on UPB (β = 0.219; p = 0.01) through organizational identification. The 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (lower and upper levels) do not contain zero. The effect of LMX on UPB is strengthened by the mediating role of organizational identification (total effect β = 0.662; p < 0.01). Thus, H4 was also supported. LMX and organizational identification together accounted for 49.5% of the total variation in UPB.

In order to test proposed moderation effects of message framing, a multi-group analysis was performed to check the significance for model invariance [71]. The gain framing group had 146 participants, whereas the loss framing group had 160 participants. The moderation effect is examined by looking at significant differences in the beta values of the regression paths for the two groups [72]. Table 6 shows results of the multi-group analysis.

Table 6.

Multi-group analysis.

As presented on Table 6, LMX exerted a significantly positive direct effect on UPB in the gain frame condition (β = 0.355, p < 0.01); yet, this positive effect was stronger in the loss frame condition (β = 0.505, p < 0.01). However, the difference between β values was only marginally significant (Δβ = 0.150; z = 1.351). Thus, we could not find enough evidence to support the moderation hypothesis (H5a) proposing that message framing would moderate the effect of LMX on UPB.

Organizational identification exerted a significantly positive effect on UPB in the gain frame condition (β = 0.459, p < 0.01). However, the magnitude of this positive effect decreased considerably in the loss-frame condition and became marginally significant (β = 0.173, p < 0.10). The difference between the parameters was statistically significant (Δβ = 0.286; z = −2.191). Thus, we concluded that message framing moderated the effect of organizational identification on UPB (H5b supported). When loss framing is used instead of gain framing, the effect of LMX on UPB increased while the effect of organizational identification decreased.

5. Discussion

These findings contribute to the existing theory on UPB by confirming the positive links between LMX-UPB [6,15] and organizational identification-UPB [5,9,13,73] in a developing country context. Previous studies have indicated that social exchange and social identity theories may be useful in explaining why employees are involved in UPB. Furthermore, according to [5], employees with a high organizational identification were more inclined to undertake UPB due to positive reciprocity views. These arguments are also supported by the findings of our research.

The findings of this study confirmed that under certain conditions high-quality LMX may lead employees to UPB. This is also in line with previous research showing that when followers have an affective attachment to their leaders, they may engage in unethical behavior in favor of the leader [6,7]. We contribute to this literature by showing that employees with a high-quality LMX, may engage in UPB, either to positively reciprocate the high quality LMX or to maintain their privileged position as a member of the in-group.

Our findings link UPB and the leadership communication literature by revealing that the leader’s message framing plays a significant role in employees’ intention to participate in UPB. Framing influences employees’ perceptions of a message and guides them to make decisions, especially in controversial situations. UPB intentions are elicited in varied magnitudes by managerial communication that highlights a potential benefit or loss [17]. Our findings take the work of [18] one step further and examine UPB from the framework of identification-LMX and leadership communication interaction. Specifically, our findings indicate that a loss framed message from the leader amplified the positive effect of LMX on UPB, while it diminished the effect of organizational identification. In contrast, when the gain frame was used, the situation was reversed. These findings suggest that the connections between organizational identification, LMX and unethical pro-organizational behavior are not always straightforward. Another explanation for the differing impacts of LMX and organizational identity on UPB can be the leader’s message framing.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the effects of LMX and organizational identification on employees’ intentions to engage in UPB, in the context of the banking and insurance industry. We examined the LMX-UPB link in depth, by probing the mediating role of organizational identification and the moderating role of leader’s message framing. Through a vignette based experimental study, we demonstrated that: (a) both LMX and organizational identification had positive effects on employees’ intentions to engage in UPB, (b) organizational identification mediated the relationship between LMX and UPB, (c) gain framed messages from leaders augmented UPB intentions of highly identified employees, and (d) loss framed messages from leaders increased UPB intentions of employees with a high quality LMX. These findings provide a number of implications for ethical decision making and management communications.

6.1. Practical Implications

Unethical behaviors have negative consequences for organizations even if they are done for the benefit of the organization. Such behavior undermines the trust of all stakeholders, damages corporate image and reputation, and thus impairs sustainable development. Therefore, unethical behaviors in the workplace for any reason should be prevented.

Our findings indicate that strong forms of identification may cause some side effects, beyond positive employee outcomes. Employees may tend to engage in UPB to defend or benefit the organization/work group when they have a sense of unity. Engaging in unethical behavior for the benefit of the organization may result from the instinct to protect in-group interests rather than the fear of individual losses. Thus, managers need to be alert to such negative consequences that a high identification may cause. Although it is aimed to favor the organization, UPB is an unethical behavior and has the potential to damage company reputation and consumer confidence. In order to eliminate a shift toward UPB, managers must explicitly highlight the delicate balance between being a loyal member and crossing moral boundaries, and closely monitor their subordinates.

It has long been assumed that leaders can prevent followers from engaging in unethical behavior by establishing high-quality LMX relationships [15]. However, leaders may inadvertently motivate followers to engage in unethical behavior that is aimed at benefiting the organization. They must be careful about what kind of role models they are in their relationship with their followers. If leaders can create a moral awareness among their followers, by using an ethical leadership style, they can reduce any form of unethical behavior [15]. In addition, they must establish clear standards to prevent UPB and should not leave unethical behavior unpunished, even if it is intended to benefit the organization.

More importantly, executives must remain alert when they use overly motivating language about major challenges. Under stressful conditions, a leader’s overemphasis on “gain” or “loss” can be misinterpreted, leading to unethical behavior (especially among highly identified employees). For this reason, leaders should avoid a discourse that can be interpreted as protecting the interests of the organization at all costs. They rather can use both framing approaches together to achieve a balance. Further, they should inform employees through formal or informal communication channels that any form of unethical behavior will cause irreparable damages to business sustainability. In short, leaders must pay special attention to what they say, who they say it to, and how they say it.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

The study has some limitations. First of all, research data is cross-sectional and collected from a convenient sample of employees working in a single industry and in a particular cultural context. Thus, findings should be evaluated carefully. Longitudinal data from different sources, based on larger and more representative samples from different industries are needed to establish external validity and generalizability of the study findings.

Design issues present another important limitation. Use of vignettes as a situational simulation to manipulate message framing is inherently artificial. The manipulations and measurements we used in the experiment simplified structures that were complex in nature. More realistic field studies can be undertaken in the future by employing factual real-world cases in various settings. Further, using single-source data and self-reported measurements of employees’ UPB intentions is another limitation. In future research, although it is difficult, cross-level data can be collected to track actual UPB behavior, or other objective measures can be adopted.

Due to the fact that the branch organization of the Turkish banking sector is composed of small groups, unethical behavior in favor of the close working group (rather than the entire organization) were examined in this research. However, an unethical behavior that will benefit the close working group in the short run can hurt the larger organization in the long run. Therefore, our findings should be carefully evaluated and compared with different organizational structures.

Finally, the current research was limited to LMX and organizational identification as antecedents of UPB. However, there may be other factors driving employees to UPB, such as fear that one will lose a job if not helping cover up a scandal, or feeling under group pressure to comply, or a desire to show loyalty etc. Future research should probe the effects of other individual (personality, values, job related affect and cognition, job stress, moral disengagement), organizational (culture, ethical climate, group pressure, trust, justice) and leadership variables to advance our understanding of the UPB phenomenon. It would also be useful to distinguish between UPB, unethical pro-leader behavior (UPL) and unethical pro-coworker behavior (UCL) to examine the relative effects of these variables. Last, but not the least, in addition to framing, it would be interesting to explore other aspects of leadership communication (formal-informal, verbal-nonverbal, negotiation-transmission) as mediating and moderating variables on UPB.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E.K. and E.A.; methodology, E.E.K. and E.A.; formal analysis, E.E.K. and E.A.; data curation, E.E.K. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.E.K.; writing—review and editing, E.A.; supervision, E.A. This research is a part of doctoral thesis of the first author (E.E.K.), which was conducted under the supervision of the second author (E.A.). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by KOCAELI UNIVERSITY, ETHICS COMMITTEE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES (protocol code E.50720 and date of approval: 23 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Experimental Scenarios adapted from [18].

| Upon graduation, Mr(s).X began working as a marketing staff at a local branch of ABC bank. Mr(s).X’s branch manager was holding a staff meeting every Monday morning. At that day’s meeting, the manager talked about the recently introduced insurance package. After briefing about this highly profitable new product, the manager asked special attention to the sale of this package in order to reach the target set for his branch. | |

| Gain Frame: At the end of the meeting, the branch manager stated that the headquarters attached great attention to the sales figures of this new product, and if they can meet the sales target, the prestige of the branch will increase considerably. He emphasized that in case of a positive result, this will be the success of all branch employees and everyone will be positively affected. He ended his speech by telling that he trusted his staff. | Loss Frame: At the end of the meeting, the branch manager stated that the headquarters attached great attention to the sales figures of this new product, and if they cannot meet the sales target, the prestige of the branch will decrease considerably. He emphasized that, in case of a negative result the responsibility belongs to all branch staff, and everyone will be negatively affected. He ended his speech by telling that he trusted his staff. |

| After the meeting, Mr(s).X noticed that this new product had some flaws. While the product did not offer any additional features, it was a difficult product to sell because the price was higher than its counterparts. In order to be successful in the sale of this product, it would be necessary to exaggerate the features of the product or hide some negative information about the product by reflecting its features better than it really is. Mr(s).X realized that in order to reach the sales target, (s)he might have to present some facts to the customer differently. | |

References

- Jones, T. Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Organizations: An Issue-Contingent Model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S. An emotion-centered model of voluntary work behavior: Some parallels between counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Folger, R. Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B. When employees do bad things for good reasons: Examining unethical pro-organizational behaviors. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B.; Mitchell, M.S. Unethical behavior in the name of the company: The moderating effect of organizational identification and positive reciprocity beliefs on unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryant, W.; Merritt, S.M. Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior and Positive Leader–Employee Relationships. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 168, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.H.; Umphress, E.E. To help my supervisor: Identification, moral identity, and unethical pro-supervisor behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effelsberg, D.; Solga, M. Transformational leaders’ in-group versus out-group orientation: Testing the link between leaders’ organizational identification, their willingness to engage in unethical pro-organizational behavior, and follower-perceived transformational leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadera, A.K.; Pratt, M.G.; Mishra, P. Constructive deviance in organizations: Integrating and moving forward. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1221–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Xiao, X. Review of the Influencing Factors of Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior. J. Hum. Resour. Sustain. Stud. 2020, 8, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mishra, M.; Ghosh, K.; Sharma, D. Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeger, N.A.; Bisel, R.S. The role of identification in giving sense to unethical organizational behavior: Defending the organization. Manag. Commun. Q. 2013, 27, 155–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.C.; Sheldon, O.J. Relaxing moral reasoning to win: How organizational identification relates to unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.T. The pathway to unethical pro-organizational behavior: Organizational identification as a joint function of work passion and trait mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriend, T.; Said, R.; Janssen, O.; Jordan, J. The Dark Side of Relational Leadership: Positive and Negative Reciprocity as Fundamental Drivers of Follower’s Intended Pro-leader and Pro-self Unethical Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.M.; Zhang, L.; Morand, D. Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior: A Moderated Mediational Model of its Transmission from Managers to Employees. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2021, 28, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.; Ziegert, J.C.; Capitano, J. The effect of leadership style, framing, and promotion regulatory focus on unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alniacik, E.; Erbas Kelebek, E.F.; Alniacik, U. The moderating role of message framing on the links between organizational identification and unethical pro-organizational behavior. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujnović-Gligorić, B.; Jakupović, S.; Šupuković, V. Ethics in Finance in Emerging Markets. In Regulations and Applications of Ethics in Business Practice. Accounting, Finance, Sustainability, Governance & Fraud: Theory and Application; Bian, J., Caliyurt, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S. Counterproductive work behavior and organisational citizenship behavior: Are they opposite forms of active behavior? Appl. Psychol. 2010, 59, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigol, T. Influence of Authentic Leadership on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: The Intermediate Role of Work Engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, G.E.; Kavanagh, M.J. An experimental examination of the effects of individual and situational factors on unethical intentions in the workplace. J. Bus. Ethics 1996, 15, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.; Detert, J.R.; Treviño, L.K.; Baker, V.L.; Mayer, D.M. Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; He, B.; Sun, X. The contagion of unethical pro-organizational behavior: From leaders to followers. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blau, P.M. Justice in Social Exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Effelsberg, D.; Solga, M.; Gurt, J. Transformational leadership and follower’s unethical behavior for the benefit of the company: A two-study investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 120, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J. Influence of Challenge–Hindrance Stressors on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Mediating Role of Emotions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Peterson, D.K. The effects of ethical pressure and power distance orientation on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The case of earnings management. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks-Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dienesch, R.M.; Liden, R.C. Leader–member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 618–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sparrowe, R.; Liden, R. Process and Structure in Leader-Member Exchange. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 522–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Maslyn, J.M. Multidimensionality of leader–member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Scandura, T.A. Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Res. Organ. Behav. 1987, 9, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A. The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Liden, R.C.; Hoel, W. Role of leadership in the employee withdrawal process. J. Appl. Psychol. 1982, 67, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandura, T.A.; Graen, G.B. Moderating effects of initial leader–member exchange status on the effects of a leadership intervention. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-C.; Lu, A.C.C.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Fang, C.-H. Ethical work climate, organizational identification, leader-member-exchange (LMX) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): A study of three star hotels in Taiwan. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, R.; Chan, K.W.; Lam, L.W. Leader–member exchange, organizational identification, and job satisfaction: A social identity perspective. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settoon, R.P.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R.C. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader–member exchange, and employee reciprocity. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.R.; Peccei, R. Organizational identification: Development and testing of a conceptually grounded measure. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDick, R. Identification in organizational contexts: Linking theory and research from social and organizational psychology. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2001, 3, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Spencer, H.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dukerich, J.M.; Kramer, R.M.; Parks, J.M. The dark side of organizational identification. In Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations; Whetten, D.A., Godfrey, P., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Blader, S.L.; Patil, S.; Packer, D.J. Organizational identification and workplace behavior: More than meets the eye. Res. Organ. Behav. 2017, 37, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmeier, C.A.L.; Homan, A.C.; Rosenauer, D.; Voelpel, S.C. Developing multiple identifications through different social interactions at work. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 25, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lu, L.; Yao, N.; Liang, C. Self-sacrificial leadership and employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior: Roles of identification with leaders and collectivism. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holladay, S.J.; Coombs, W.T. Communication visions: An exploration of the role of delivery in the creation of leader charisma. Manag. Commun. Q. 1993, 6, 405–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, B.H.; Lee, J. Leader-member exchange and organizational communication satisfaction in multiple contexts. J. Bus. Commun. 2002, 39, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R. Strategic employee communication: Transformational leadership, communication channels, and employee satisfaction. Manag. Commun. Q. 2014, 28, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, B.D.; Gigliotti, R.A. Communication: Sine qua non of organizational leadership theory and practice. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2017, 54, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Kollar, L.M. Testing moderators of message framing effect: A motivational approach. Commun. Res. 2015, 42, 626–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCaffery, E.J.; Baron, J. Thinking about tax. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2006, 12, 106–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.P.; Schneider, S.L.; Gaeth, G.J. All Frames Are Not Created Equal: A Typology and Critical Analysis of Framing Effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 76, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kühberger, A. The influence of framing on risky decisions: A meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 75, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bastons, M. The Role of Virtues in the Framing of Decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 78, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Bañón-Gomis, A.; Linuesa-Langreo, J. Impacts of peers’ unethical behavior on employees’ ethical intention: Moderated mediation by Machiavellian orientation. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.C. Turkish Banks and Digitalization: Policy Recommendations from a Qualitative Study. J. BRSA 2020, 14, 145–174. [Google Scholar]

- Tuna, K. Impacts of Covid-19 Pandemic on Turkish Banking Sector Employment. Istanb. J. Econ. 2021, 71, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin, J.; Lim, J. Multigroup Analysis, AMOS Plugin. Gaskination’s StatWiki. Available online: http://statwiki.gaskination.com (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Yin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L. Employee-Oriented CSR and Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: The Role of Perceived Insider Status and Ethical Climate Rules. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).