Synthesis and Pharmacological Properties of Novel Esters Based on Monocyclic Terpenes and GABA

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

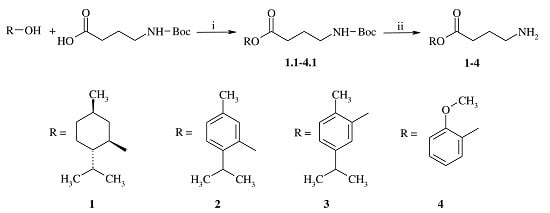

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Pharmacology

2.2.1. Antinociception Testing

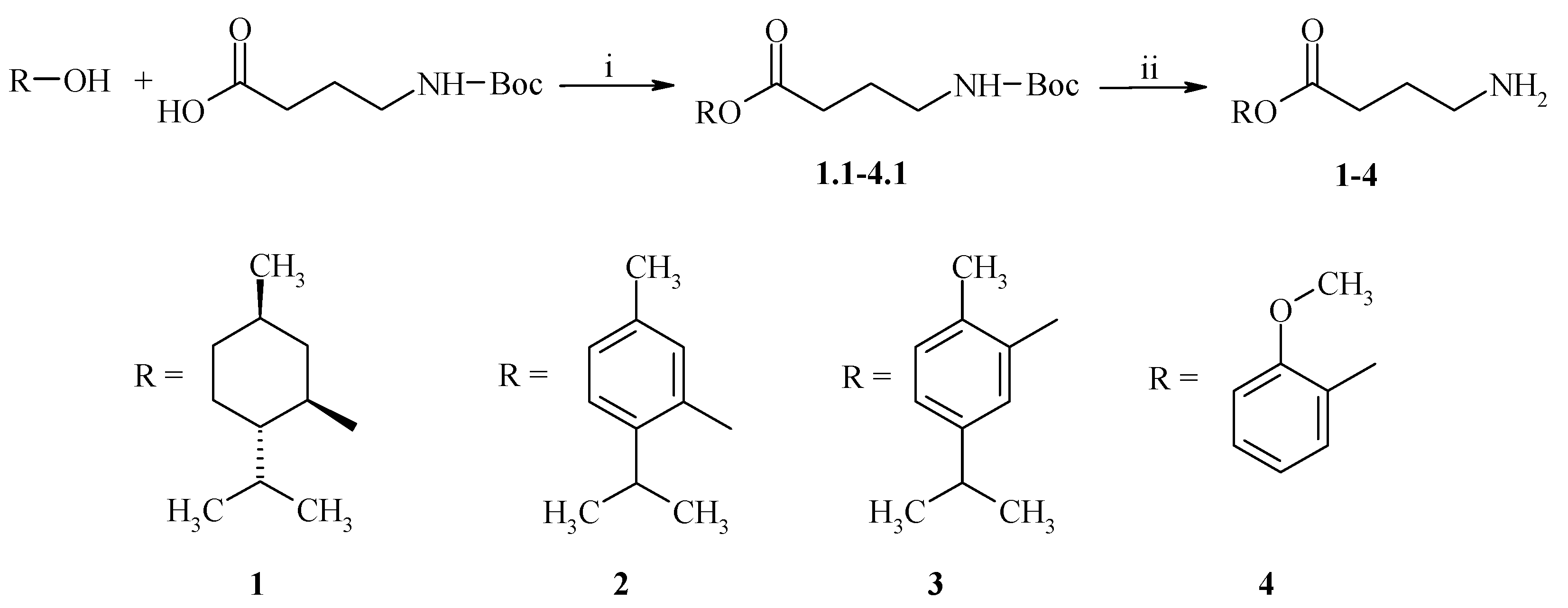

2.2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

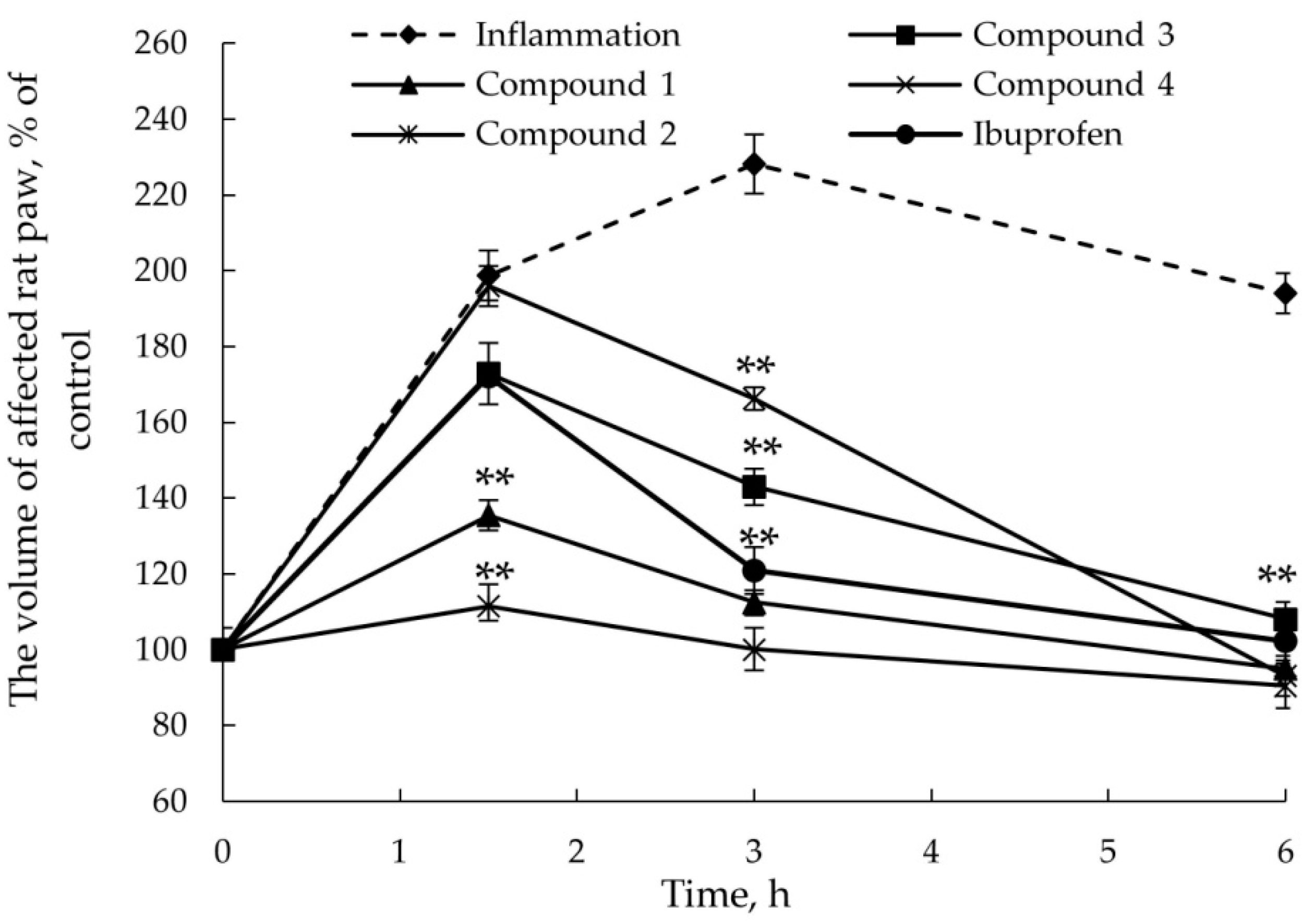

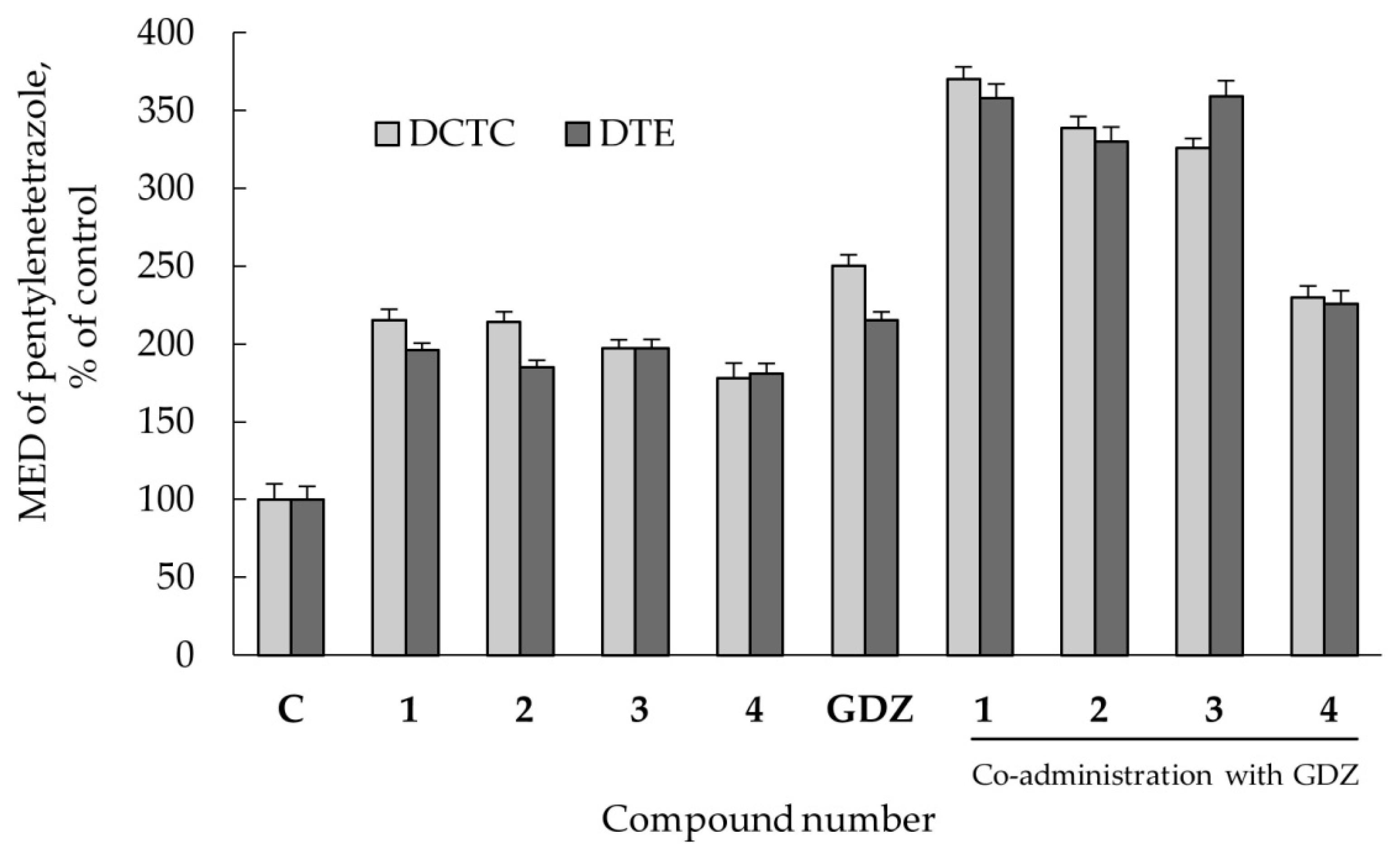

2.2.3. Anticonvulsant Action

2.2.4. Co-Administration Effect of Gidazepam and GABA Esters 1–4

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

3.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of GABA Esters 1–4

3.3. Animals

3.4. Drug Administration

3.5. Antinociception Testing

3.6. AITC-Induced Acute Inflammatory Model

3.7. Pentylenetetrazole-Induced Convulsions in Mice

3.8. Co-Administration Effect of Gidazepam and GABA Esters 1–4

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Premkumar, L.S. Transient receptor potential channels as targets for phytochemicals. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatachalam, K.; Montell, C. TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 387–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calixto, J.B.; Kassuya, C.A.; André, E.; Ferreira, J. Contribution of natural products to the discovery of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels family and their functions. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 106, 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, B.K.; Karim, S.; Goodchild, A.K.; Vaughan, C.W.; Drew, G.M. Menthol enhances phasic and tonic GABAA receptor-mediated currents in midbrain periaqueductal grey neurons. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 2803–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, H.; Mizogami, M. Comparative interactions of anesthetic alkylphenols with lipid membranes. Open J. Anesthesiol. 2014, 4, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmin, L.; Wu, M.V.; Ohara, P.T. GABA puts a stop to pain. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 2004, 3, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanack, C.; Moroni, M.; Lima, W.C.; Wende, H.; Kichner, M.; Adelfinger, L.; Schrenk-Siemens, K.; Tappe-Theodor, A.; Wetzel, C.; Kuich, P.H.; et al. GABA blocks pathological but not acute TRPV1 pain signals. Cell 2015, 160, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesterkina, M.V.; Kravchenko, I.A. Synthesis and anticonvulsant activity of menthyl γ-aminobutyrate. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2016, 52, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterkina, M.V.; Kravchenko, I.A. Thymol ester gamma-aminobutyric acid: Synthesis and anticonvulsant activity. ONU Herald. 2015, 20, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozdnev, V.F. Activation of carboxylic acids with pyrocarbonates. Esterification of N-acylamino acids with secondary alcohols using di-tret-butylpyrocarbonate—Pyridine as the condensing reagents. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 1985, 11, 725–732. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, M.M.; McAlexander, M.A.; Biro, T.; Szallasi, A. Transient receptor potential channels as therapeutic targets. Nature 2011, 10, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesterkina, M.V.; Kravchenko, I.A. Analgesic activity of novel GABA esters after transdermal delivery. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Story, G.M. The emerging role of TRP channels in mechanisms of temperature and pain sensation. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2006, 4, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leffler, A.L.; Fischer, M.J.; Rehner, D.; Kienel, S.; Kistner, K.; Sauer, S.K.; Narender, R.G.; Reeh, P.W.; Nau, C. The vanilloid receptor TRPV1 is activated and sensitized by local anesthetics in rodent sensory neurons. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perin-Martins, A.; Teixeira, J.M.; Tambeli, C.H.; Parada, C.A.; Fischer, L. Mechanisms underlying transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1)-mediated hyperalgesia and edema. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2013, 18, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moilanen, L.J.; Laavola, M.; Kukkonen, M.; Korhonen, R.; Leppänen, T.; Högestätt, E.D.; Zygmunt, P.M.; Nieminen, R.M.; Moilanen, E. TRPA1 contributes to the acute inflammatory response and mediates carrageenan-induced paw edema in the mouse. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curia, G.; Lucchi, C.; Vinet, J.; Gualtieri, F.; Marinelli, C.; Torsello, A.; Costantino, L.; Biagini, G. Pathophysiogenesis of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: Is prevention of damage antiepileptogenic? Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deyn, P.P.; D’Hooge, R.; Marescau, B.; Pei, Y.-Q. Chemical models of epilepsy with some reference to their applicability in the development of anticonvulsants. Epilepsy Res. 1992, 12, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Guimarães, A.G.; Araújo, B.E.S.; Oliveira, G.F.; Santana, M.T.; Moreira, F.V.; Santos, M.R.V.; Cavalcanti, S.C.H.; Júnior, W.D.L.; Botelho, M.A.; et al. Carvacrol, (−)-borneol and citral reduce convulsant activity in rodents. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 6566–6572. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, D.A.; Bujons, J.; Vale, C.; Suñol, C. Allosteric positive interaction of thymol with the GABAA receptor in primary cultures of mouse cortical neurons. Neuropharmacology 2006, 50, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheedarala, R.K.; Sunkara, V.; Park, J.W. Facile synthesis of second-generation dendrons with an orthogonal functional group at the focal point. Synth. Commun. 2009, 39, 1966–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałat, K.; Filipek, B. Antinociceptive activity of transient receptor potential channel TRPV1, TRPA1, and TRPM8 antagonists in neurogenic and neuropathic pain models in mice. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2015, 16, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Reaction Time (in s) | Compound | Reaction Time (in s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 71.3 ± 1.8 | 4 | 25.3 ± 1.5 |

| Benzocaine | 48.0 ± 2.0 | 5 | 6.8 ± 1.2 |

| 1 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 6 | 25.3 ± 3.8 |

| 2 | 20.3 ± 5.8 | 7 | 34.5 ± 2.2 |

| 3 | 22.8 ± 4.3 | 8 | 20.7 ± 2.8 |

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nesterkina, M.; Kravchenko, I. Synthesis and Pharmacological Properties of Novel Esters Based on Monocyclic Terpenes and GABA. Pharmaceuticals 2016, 9, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph9020032

Nesterkina M, Kravchenko I. Synthesis and Pharmacological Properties of Novel Esters Based on Monocyclic Terpenes and GABA. Pharmaceuticals. 2016; 9(2):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph9020032

Chicago/Turabian StyleNesterkina, Mariia, and Iryna Kravchenko. 2016. "Synthesis and Pharmacological Properties of Novel Esters Based on Monocyclic Terpenes and GABA" Pharmaceuticals 9, no. 2: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph9020032

APA StyleNesterkina, M., & Kravchenko, I. (2016). Synthesis and Pharmacological Properties of Novel Esters Based on Monocyclic Terpenes and GABA. Pharmaceuticals, 9(2), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph9020032