Cannabidiol Regulates CD47 Expression and Apoptosis in Jurkat Leukemic Cells Dependent upon VDAC-1 Oligomerization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

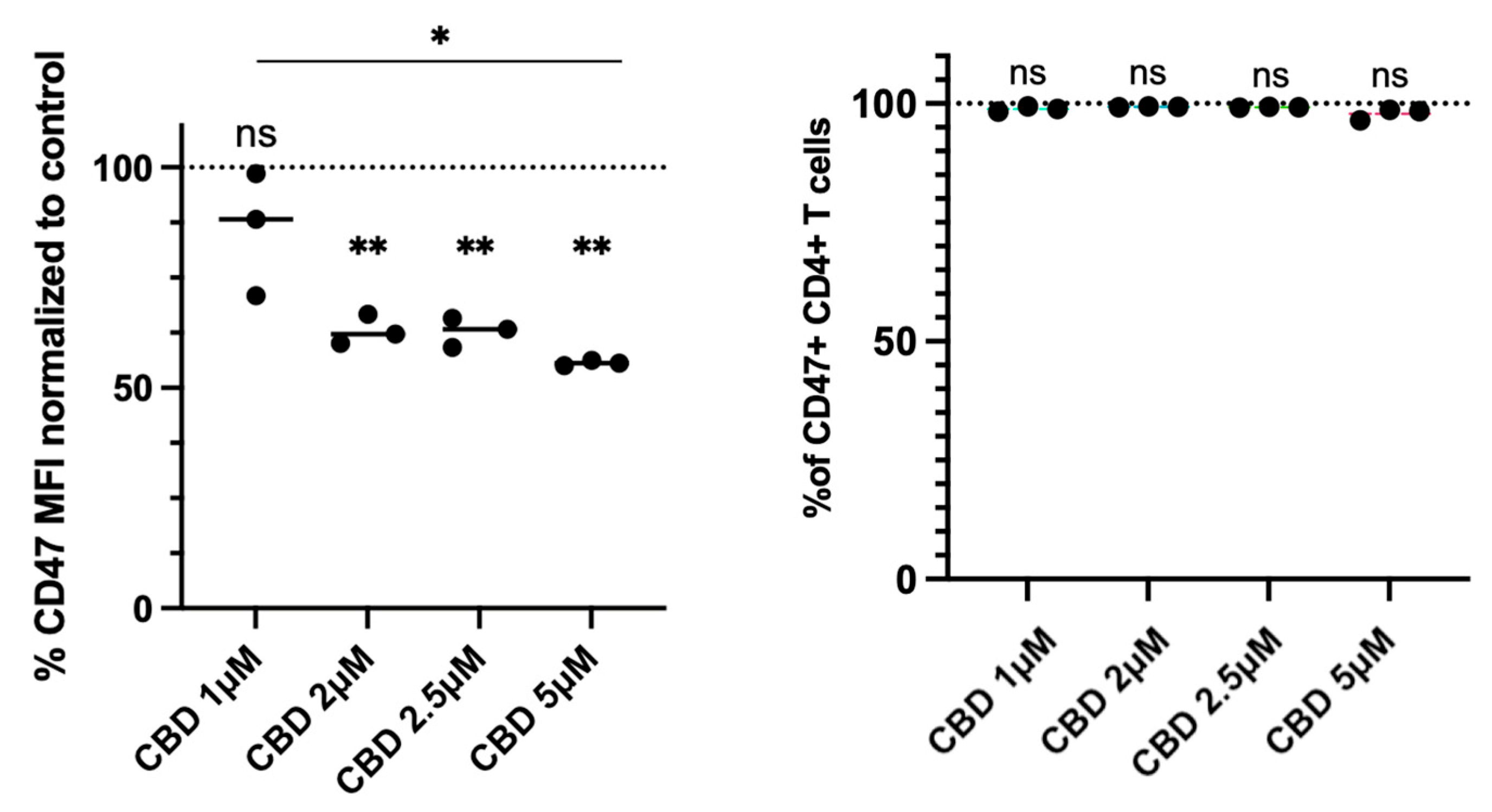

2.1. CBD Reduces CD47 Expression in Jurkat Cells

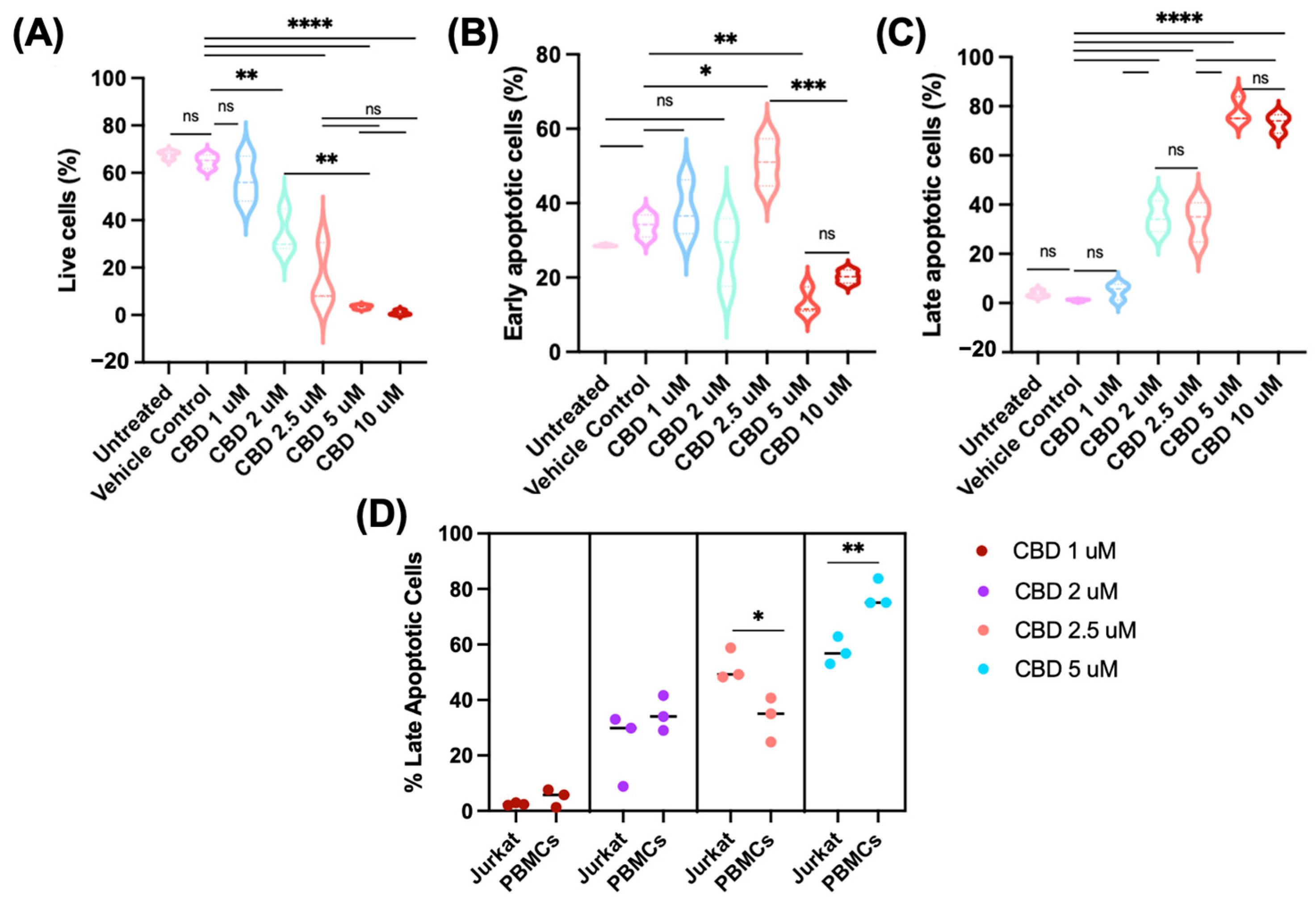

2.2. CBD Induces Apoptosis in Jurkat Cells

2.3. CBD Reduces CD47 Expression in Human Primary CD4+ T Cells

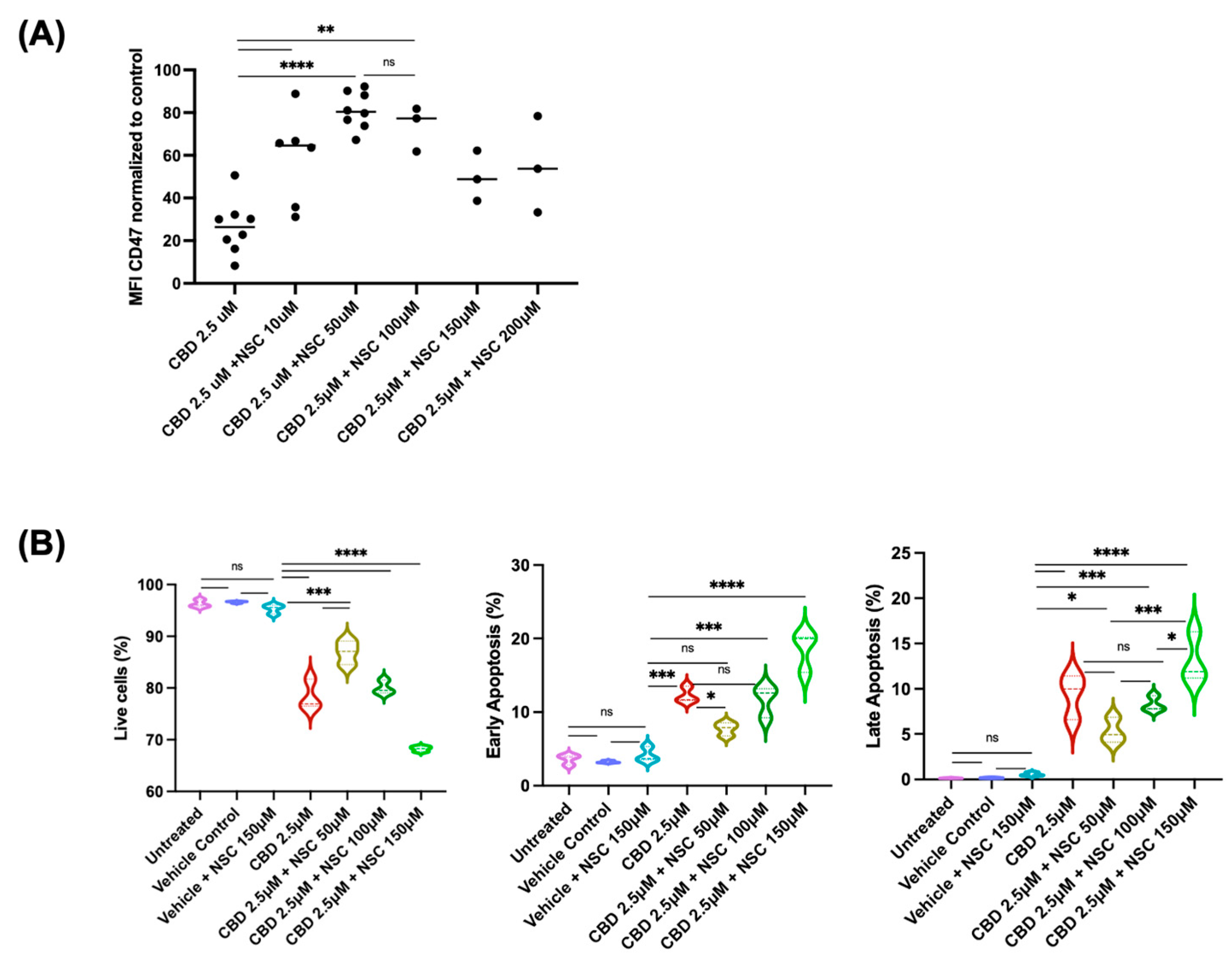

2.4. Mechanisms Underlying CBD-Induced Reduction in CD47 Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Line and Culture Conditions

4.2. Cell Treatments and Reagents

4.3. Light Microscopy

4.4. Flow Cytometry for CD47 Expression

4.5. Determination of Apoptosis

4.6. Treatments and Staining of CD4+ T-Lymphocytes from Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs)

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salz, T.; Meza, A.M.; Chino, F.; Mao, J.J.; Raghunathan, N.J.; Jinna, S.; Brens, J.; Furberg, H.; Korenstein, D. Cannabis use among recently treated cancer patients: Perceptions and experiences. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Lev Schleider, L.; Mechoulam, R.; Lederman, V.; Hilou, M.; Lencovsky, O.; Betzalel, O.; Shbiro, L.; Novack, V. Prospective analysis of safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in large unselected population of patients with cancer. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 49, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Li, X.; Nie, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, S. Disorders of cancer metabolism: The therapeutic potential of cannabinoids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 157, 113993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B.; Ramer, R. Cannabinoids as anticancer drugs: Current status of preclinical research. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, F.; Grandi, V.; Banerjee, A.; Trant, J.F. Cannabinoids and Cannabinoid Receptors: The Story so Far. iScience 2020, 23, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, E.M.; Parker, L.A. Constituents of Cannabis Sativa. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1264, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, D.; Anis, O.; Poulin, P.; Koltai, H. Chronological Review and Rational and Future Prospects of Cannabis-Based Drug Development. Molecules 2020, 25, 4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigano, M.; Wang, L.; As’sadiq, A.; Samarani, S.; Ahmad, A.; Costiniuk, C.T. Impact of cannabinoids on cancer outcomes in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1497829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K. Cannabidiol (CBD) in Cancer Management. Cancers 2022, 14, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, E.S.; Watters, A.K.; MacKenzie, D., Jr.; Granat, L.M.; Zhang, D. Cannabidiol (CBD) as a Promising Anti-Cancer Drug. Cancers 2020, 12, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, M.; Hage, M.E.; Shebaby, W.; Al Toufaily, S.; Ismail, J.; Naim, H.Y.; Mroueh, M.; Rizk, S. The molecular anti-metastatic potential of CBD and THC from Lebanese Cannabis via apoptosis induction and alterations in autophagy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, E.S.A.; Asevedo, E.A.; Duarte-Almeida, J.M.; Nurkolis, F.; Syahputra, R.A.; Park, M.N.; Kim, B.; Couto, R.O.D.; Ribeiro, R. Mechanisms of Cell Death Induced by Cannabidiol Against Tumor Cells: A Review of Preclinical Studies. Plants 2025, 14, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivas-Aguirre, M.; Torres-López, L.; Valle-Reyes, J.S.; Hernández-Cruz, A.; Pottosin, I.; Dobrovinskaya, O. Cannabidiol directly targets mitochondria and disturbs calcium homeostasis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKallip, R.J.; Jia, W.; Schlomer, J.; Warren, J.W.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells: A novel role of cannabidiol in the regulation of p22phox and Nox4 expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, E.; Gelfand, A.; Procaccia, S.; Berman, P.; Meiri, D. Cannabinoid combination targets NOTCH1-mutated T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia through the integrated stress response pathway. eLife 2024, 12, RP90854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hail, D.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. VDAC1-interacting anion transport inhibitors inhibit VDAC1 oligomerization and apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 1612–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmerman, N.; Ben-Hail, D.; Porat, Z.; Juknat, A.; Kozela, E.; Daniels, M.P.; Connelly, P.S.; Leishman, E.; Bradshaw, H.B.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; et al. Direct modulation of the outer mitochondrial membrane channel, voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1) by cannabidiol: A novel mechanism for cannabinoid-induced cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Chandra, H.; Singh, A.; Babu, R. CD47/SIRPα pathways: Functional diversity and molecular mechanisms. World J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 16, 108045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polara, R.; Ganesan, R.; Pitson, S.M.; Robinson, N. Cell autonomous functions of CD47 in regulating cellular plasticity and metabolic plasticity. Cell Death Differ. 2024, 31, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raetz, E.A.; Teachey, D.T. T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2016, 2016, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, K.M. Optimal approach to T-cell ALL. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2022, 2022, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz-Cort, A.; Müller-Sánchez, C.; Espel, E. Anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effect of cannabidiol on human cancer cell lines in presence of serum. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carkaci-Salli, N.; Raup-Konsavage, W.M.; Karelia, D.; Sun, D.; Jiang, C.; Lu, J.; Vrana, K.E. Cannabinoids as Potential Cancer Therapeutics: The Concentration Conundrum. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2024, 9, e1159–e1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, H.L.; McHann, M.C.; De Selle, H.; Dancel, C.L.; Redondo, J.L.; Molehin, D.; German, N.A.; Trasti, S.; Pruitt, K.; Castro-Piedras, I.; et al. Chronic Administration of Cannabinoid Receptor 2 Agonist (JWH-133) Increases Ectopic Ovarian Tumor Growth and Endocannabinoids (Anandamide and 2-Arachidonoyl Glycerol) Levels in Immunocompromised SCID Female Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 823132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi-Carmona, M.; Barth, F.; Millan, J.; Derocq, J.M.; Casellas, P.; Congy, C.; Oustric, D.; Sarran, M.; Bouaboula, M.; Calandra, B.; et al. SR 144528, the first potent and selective antagonist of the CB2 cannabinoid receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 284, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Rangel, E.; López-Méndez, M.C.; García, L.; Guerrero-Hernández, A. DIDS (4,4′-Diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate) directly inhibits caspase activity in HeLa cell lysates. Cell Death Discov. 2015, 1, 15037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.M.; Kostrzewa, M.; Marolda, V.; Cerasuolo, M.; Maccarinelli, F.; Coltrini, D.; Rezzola, S.; Giacomini, A.; Mollica, M.P.; Motta, A.; et al. Cannabidiol alters mitochondrial bioenergetics via VDAC1 and triggers cell death in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 189, 106683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, S.K.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Hong, J.; Park, K.S.; Park, I.C.; Jin, H.O. Inhibition of VDAC1 oligomerization blocks cysteine deprivation-induced ferroptosis via mitochondrial ROS suppression. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golub, V.; Reddy, D.S. Cannabidiol Therapy for Refractory Epilepsy and Seizure Disorders. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1264, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammendolia, I.; Mannucci, C.; Cardia, L.; Calapai, G.; Gangemi, S.; Esposito, E.; Calapai, F. Pharmacovigilance on cannabidiol as an antiepileptic agent. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1091978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyravian, N.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S.; Jimenez, J.J. The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Cannabidiol (CBD) on Acne. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 2795–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, R.; Bar-Lev, T.H.; Lavi Kutchuk, L.A.; Schaffer, T.; Mirelman, D.; Pelles-Avraham, S.; Wolf, I.; Bar-Lev Schleider, L. Comparative Effects of THC and CBD on Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: Insights from a Large Real-World Self-Reported Dataset. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeli, M.; Dehabadi, M.D.; Khaleghi, A.A. Cannabidiol as a novel therapeutic agent in breast cancer: Evidence from literature. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacohen, M.; Stolar, O.E.; Berkovitch, M.; Elkana, O.; Kohn, E.; Hazan, A.; Heyman, E.; Sobol, Y.; Waissengreen, D.; Gal, E.; et al. Children and adolescents with ASD treated with CBD-rich cannabis exhibit significant improvements particularly in social symptoms: An open label study. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, A.S.; Marie, M.A.; Sheweita, S.A. Novel mechanism of cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines. Breast 2018, 41, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhao, P.Y.; Yang, X.P.; Li, H.; Hu, S.D.; Xu, Y.X.; Du, X.H. Cannabidiol regulates apoptosis and autophagy in inflammation and cancer: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1094020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayeva, M.; Srdanovic, I. Non-linear plasma protein binding of cannabidiol. J. Cannabis Res. 2024, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cai, A.; Li, H.; Deng, N.; Cho, B.P.; Seeram, N.P.; Ma, H. Characterization of molecular interactions between cannabidiol and human plasma proteins (serum albumin and γ-globulin) by surface plasmon resonance, microcalorimetry, and molecular docking. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 214, 114750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.X.; Zhang, X.; Tang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, L.; Song, C.H.; Li, W.; Shi, H.P.; Cong, M.H. Comprehensive evaluation of serum hepatic proteins in predicting prognosis among cancer patients with cachexia: An observational cohort study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, P.; Elsohly, M.; Hill, K.P. Cannabidiol Interactions with Medications, Illicit Substances, and Alcohol: A Comprehensive Review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. Integrin-associated protein (CD47): An unusual activator of G protein signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 1499–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, P.; Hilarius-Stokman, P.; de Korte, D.; van den Berg, T.K.; van Bruggen, R. CD47 functions as a molecular switch for erythrocyte phagocytosis. Blood 2012, 119, 5512–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, L.; Chen, L.; Huang, W.; Peng, S.; Wang, C.; Liao, H.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Lv, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Harnessing the innate immune system: A novel bispecific antibody targeting CD47 and CD24 for selective tumor clearance. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e013283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eladl, E.; Tremblay-LeMay, R.; Rastgoo, N.; Musani, R.; Chen, W.; Liu, A.; Chang, H. Role of CD47 in Hematological Malignancies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenborg, P.A.; Zheleznyak, A.; Fang, Y.F.; Lagenaur, C.F.; Gresham, H.D.; Lindberg, F.P. Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science 2000, 288, 2051–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cham, L.B.; Adomati, T.; Li, F.; Ali, M.; Lang, K.S. CD47 as a Potential Target to Therapy for Infectious Diseases. Antibodies 2020, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Niu, C. Role of CD47-SIRPα Checkpoint in Nanomedicine-Based Anti-Cancer Treatment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 887463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoba, O.T.; Ayinde, K.S.; Lateef, O.M.; Akintubosun, M.O.; Lawal, K.A.; Adelusi, T.I. Is the new angel better than the old devil? Challenges and opportunities in CD47- SIRPα-based cancer therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2023, 184, 103939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Bian, Z.; Shi, L.; Niu, S.; Ha, B.; Tremblay, A.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Paluszynski, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Loss of Cell Surface CD47 Clustering Formation and Binding Avidity to SIRPα Facilitate Apoptotic Cell Clearance by Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Sun, Y.; Xie, L.; Tan, X.; Wang, P.; Xu, S. Targeting QPCTL: An Emerging Therapeutic Opportunity. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pinilla, E.; Varani, K.; Reyes-Resina, I.; Angelats, E.; Vincenzi, F.; Ferreiro-Vera, C.; Oyarzabal, J.; Canela, E.I.; Lanciego, J.L.; Nadal, X.; et al. Binding and Signaling Studies Disclose a Potential Allosteric Site for Cannabidiol in Cannabinoid CB(2) Receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laprairie, R.B.; Bagher, A.M.; Kelly, M.E.; Denovan-Wright, E.M. Cannabidiol is a negative allosteric modulator of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 4790–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bie, B.; Wu, J.; Foss, J.F.; Naguib, M. An overview of the cannabinoid type 2 receptor system and its therapeutic potential. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2018, 31, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olabiyi, B.F.; Schmoele, A.C.; Beins, E.C.; Zimmer, A. Pharmacological blockade of cannabinoid receptor 2 signaling does not affect LPS/IFN-γ-induced microglial activation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, F.; Morelli, M.B.; Nabissi, M.; Marinelli, O.; Zeppa, L.; Aguzzi, C.; Santoni, G.; Amantini, C. Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channels in Haematological Malignancies: An Update. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majhi, R.K.; Sahoo, S.S.; Yadav, M.; Pratheek, B.M.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Goswami, C. Functional expression of TRPV channels in T cells and their implications in immune regulation. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 2661–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Takizawa, Y.; Kainuma, T.; Inoue, J.; Mikawa, T.; Shibata, T.; Suzuki, H.; Tashiro, S.; Kurumizaka, H. DIDS, a chemical compound that inhibits RAD51-mediated homologous pairing and strand exchange. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 3367–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Verma, A. VDAC1 at the Intersection of Cell Metabolism, Apoptosis, and Diseases. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Maldonado, E.N.; Krelin, Y. VDAC1 at the crossroads of cell metabolism, apoptosis and cell stress. Cell Stress 2017, 1, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; Ben-Hail, D.; Admoni, L.; Krelin, Y.; Tripathi, S.S. The mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel 1 in tumor cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 2547–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Angelova, A.; Garamus, V.M.; Angelov, B.; Tu, S.; Kong, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Zou, A. Mitochondrial Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel 1-Hexokinase-II Complex-Targeted Strategy for Melanoma Inhibition Using Designed Multiblock Peptide Amphiphiles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 35281–35293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shteinfer-Kuzmine, A.; Santhanam, M.; Shoshan-Barmatz, V. VDAC1-Based Peptides as Potential Modulators of VDAC1 Interactions with Its Partners and as a Therapeutic for Cancer, NASH, and Diabetes. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consroe, P.; Laguna, J.; Allender, J.; Snider, S.; Stern, L.; Sandyk, R.; Kennedy, K.; Schram, K. Controlled clinical trial of cannabidiol in Huntington’s disease. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991, 40, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Kong, Q.; Guan, X.; Lei, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, H.; Yao, X.; Liang, S.; An, X.; et al. Inhibition of Integrin α(v)β(3)-FAK-MAPK signaling constrains the invasion of T-ALL cells. Cell Adh. Migr. 2023, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Roberts, D.D. Emerging functions of thrombospondin-1 in immunity. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 155, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yao, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.M.; Kaplan, B.L.F. Immune Responses Regulated by Cannabidiol. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2020, 5, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Wey, S.P.; Liao, M.H.; Hsu, W.L.; Wu, H.Y.; Jan, T.R. A comparative study on cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in murine thymocytes and EL-4 thymoma cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2008, 8, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Samarani, S.; Fadzeyeva, E.; Vigano, M.; As’sadiq, A.; Vulesevic, B.; Ahmad, A.; Costiniuk, C.T. Cannabidiol Regulates CD47 Expression and Apoptosis in Jurkat Leukemic Cells Dependent upon VDAC-1 Oligomerization. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010095

Wang L, Samarani S, Fadzeyeva E, Vigano M, As’sadiq A, Vulesevic B, Ahmad A, Costiniuk CT. Cannabidiol Regulates CD47 Expression and Apoptosis in Jurkat Leukemic Cells Dependent upon VDAC-1 Oligomerization. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010095

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lixing, Suzanne Samarani, Evgenia Fadzeyeva, MariaLuisa Vigano, Alia As’sadiq, Branka Vulesevic, Ali Ahmad, and Cecilia T. Costiniuk. 2026. "Cannabidiol Regulates CD47 Expression and Apoptosis in Jurkat Leukemic Cells Dependent upon VDAC-1 Oligomerization" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010095

APA StyleWang, L., Samarani, S., Fadzeyeva, E., Vigano, M., As’sadiq, A., Vulesevic, B., Ahmad, A., & Costiniuk, C. T. (2026). Cannabidiol Regulates CD47 Expression and Apoptosis in Jurkat Leukemic Cells Dependent upon VDAC-1 Oligomerization. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010095