Natamycin in Food and Ophthalmology: Knowledge Gaps and Emerging Insights from Zebrafish Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism of Action

3. Chemical Properties and Pharmacodynamic Profile

4. Toxicity Assessment in Food Applications

| Compound/Study | Species/Model | Route of Administration | Dose/Concentration | Duration | Endpoints/Outcomes Assessed | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natamycin (general use) | Human, animal, in vitro | Topical, oral (poor absorption) | Not specified | Chronic (food/medicine) | Low systemic toxicity, rare resistance, proven food safety | [48,55,64,65] |

| Natamycin (food preservative) | Human exposure model | Oral (dietary) | Not specified; enhanced with cyclodextrins | Chronic dietary exposure | Effects on gut flora, resistance development, dietary safety thresholds | [55] |

5. Toxicity Assessment in Ophthalmic Applications

6. General Toxicological Considerations Across Applications

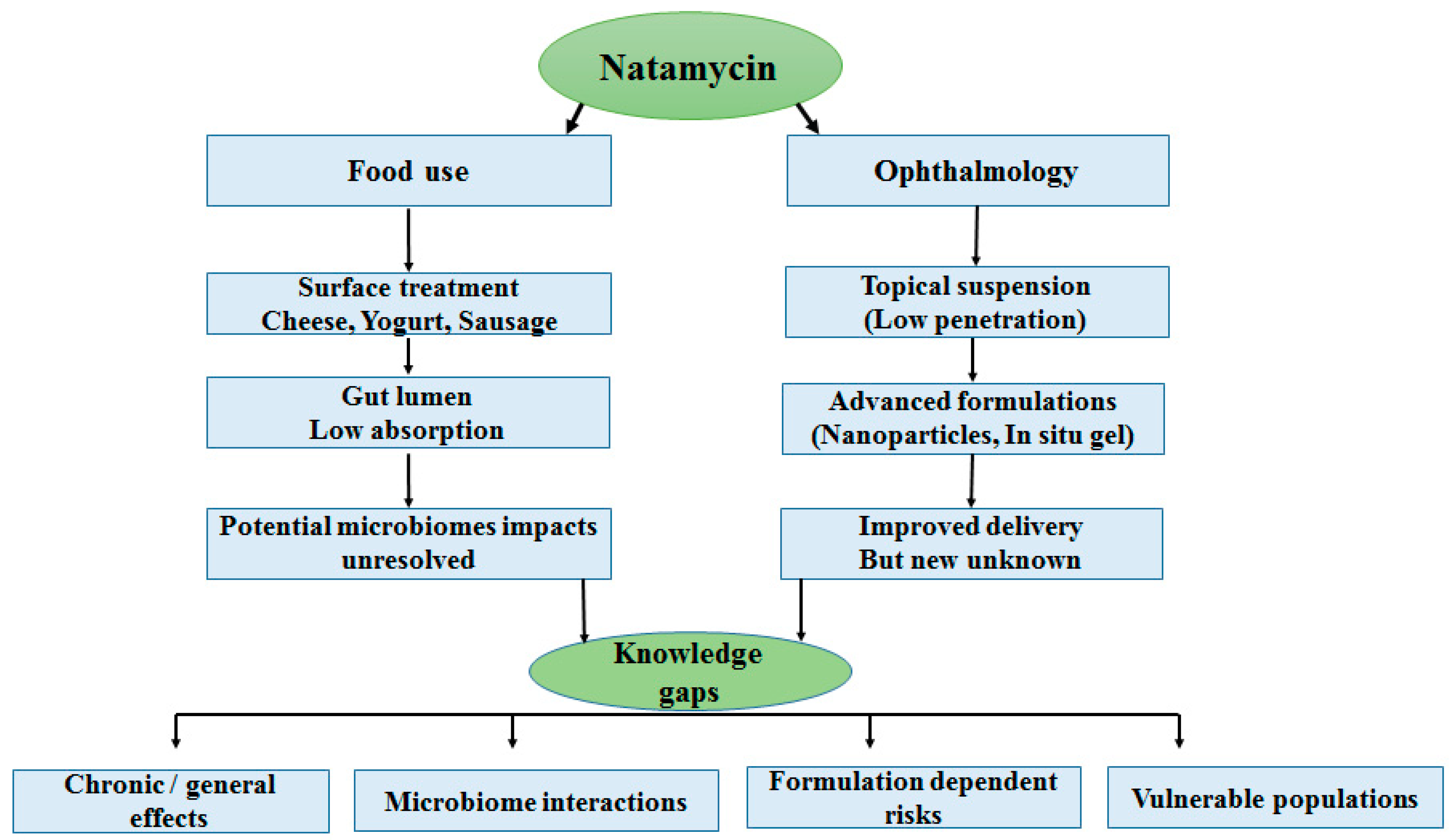

7. Knowledge Gaps and Emerging Concerns

7.1. Lack of Long-Term, Chronic, and Generational Studies

7.2. Unknown Effects on the Microbiome

7.3. Safety of Advanced Drug-Delivery Systems

7.4. Insufficient Data for Vulnerable Populations

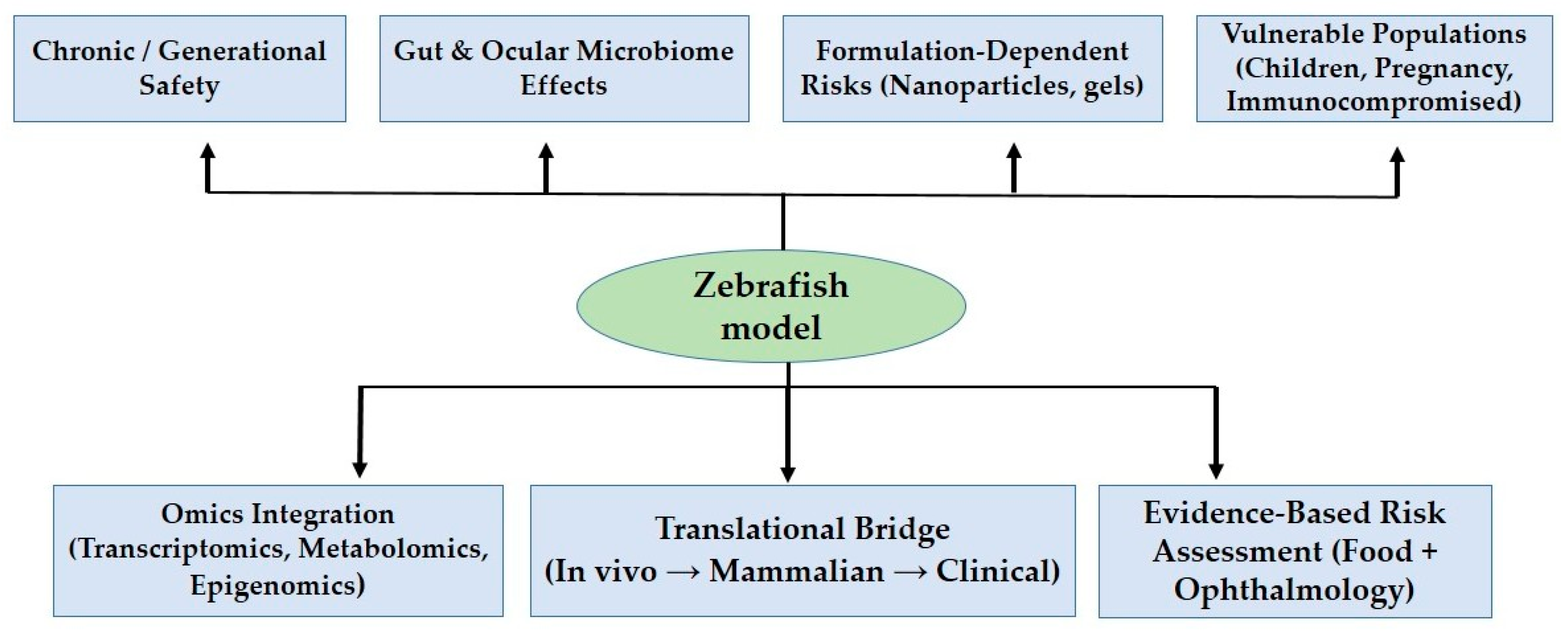

8. Zebrafish as a Model System

9. Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GRAS | Generally recognized as safe |

| MRLs | Maximum residue limits |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| ADI | Acceptable daily intake |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| AMB | Amphotericin B |

| NLCs | Nanostructured lipid carriers |

| LDS | Lipid-based delivery systems |

References

- Meena, M.; Prajapati, P.; Ravichandran, C.; Sehrawat, R. Natamycin: A natural preservative for food applications—A review. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 1481–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.; Doan, C. Natamycin. In Antimicrobials in Food; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, M.C.; Chaudhari, P.; Lewis, S.A. Natamycin Ocular Delivery: Challenges and Advancements in Ocular Therapeutics. Adv. Ther. 2023, 40, 3332–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khames, A.; Khaleel, M.; El-Badawy, M.; El-Nezhawy, A. Natamycin solid lipid nanoparticles—Sustained ocular delivery system of higher corneal penetration against deep fungal keratitis: Preparation and optimization. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 2515–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, K.; Rizg, W.; Alkhalidi, H.; Abualsunun, W.; Bakhaidar, R.; Almehmady, A.; Alghaith, A.; Alshehri, S.; Sisi, A. Nanocubosomal based in situ gel loaded with natamycin for ocular fungal diseases: Development, optimization, in-vitro, and in-vivo assessment. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 1836–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, L.; Clemente, I.; Gennari, A.; Gabbricci, G.; Pepi, S.; Leone, G.; Bonechi, C.; Rossi, C.; Mattioli, S.; Detta, N.; et al. Physiochemical Characterization of Lipidic Nanoformulations Encapsulating the Antifungal Drug Natamycin. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohira, H.; Shankar, S.; Yadav, S.; Shah, S.; Chugh, A. Enhanced in vivo antifungal activity of novel cell penetrating peptide Natamycin conjugate for efficient fungal keratitis management. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 600, 120484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpura, C.; Garry, E.; Honig, N.; Case, A.; Rassen, J. The Role of Real-World Evidence in FDA-Approved New Drug and Biologics License Applications. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 111, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanshahi, M.; Gregg, K.; Davis, G.; Ndu, A.; Miller, V.; Vockley, J.; Ollivier, C.; Franolic, T.; Sakai, S. The Use of External Controls in FDA Regulatory Decision Making. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2021, 55, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific support for preparing an EU position in the 50th Session of the Codex Committee on Pesticide Residues (CCPR). EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velpandian, T.; Nirmal, J.; Sharma, H.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, N.; Halder, N. Novel Water Soluble Sterile Natamycin Formulation (Natasol) for Fungal Keratitis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 163, 105857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tevyashova, A.; Efimova, S.; Alexandrov, A.; Ghazy, E.; Bychkova, E.; Solovieva, S.; Zatonsky, G.; Grammatikova, N.; Dezhenkova, L.; Pereverzeva, E.; et al. Semisynthetic Amides of Polyene Antibiotic Natamycin. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, F.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Hu, L.; Peng, X.; Zhao, G.; Lin, J. Macrophage Membrane-Coated Nanoparticles for the Delivery of Natamycin Exhibit Increased Antifungal and Anti-Inflammatory Activities in Fungal Keratitis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 59777–59788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilakapati, J.; Mehendale, H.M. Butyrophenones. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, P.; Kaliyaperumal, R. Global and Indian Regulatory Frameworks for Pharmaceutical Excipients, APIs, and Formulations: Challenges and Harmonization Strategies. Recent Adv. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2025, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Jain, A.; Tiwari, A.; Jain, S. Preformulation considerations of Natamycin and development of Natamycin loaded niosomal formulation. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 5, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welscher, Y.M.T.; Napel, H.H.T.; Balagué, M.M.; Souza, C.M.; Riezman, H.; De Kruijff, B.; Breukink, E. Natamycin blocks fungal growth by binding specifically to ergosterol without permeabilizing the membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 6393–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welscher, Y.M.T.; Van Leeuwen, M.R.; De Kruijff, B.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Breukink, E. Polyene antibiotic that inhibits membrane transport proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11156–11159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szomek, M.; Reinholdt, P.; Walther, H.L.; Scheidt, H.A.; Müller, P.; Obermaier, S.; Poolman, B.; Kongsted, J.; Wüstner, D. Natamycin sequesters ergosterol and interferes with substrate transport by the lysine transporter Lyp1 from yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2022, 1864, 184012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkerman, V.; Scheidt, H.; Reinholdt, P.; Bashawat, M.; Szomek, M.; Lehmann, M.; Wessig, P.; Covey, D.; Kongsted, J.; Müller, P.; et al. Natamycin interferes with ergosterol-dependent lipid phases in model membranes. BBA Adv. 2023, 4, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, A.; Pavinatto, F.; Oliveira, O.; Gonzales, E. The negligible effects of the antifungal natamycin on cholesterol-dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine monolayers may explain its low oral and topical toxicity for mammals. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 122, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szomek, M.; Akkerman, V.; Lauritsen, L.; Walther, H.; Juhl, A.; Thaysen, K.; Egebjerg, J.; Covey, D.; Lehmann, M.; Wessig, P.; et al. Ergosterol mediates aggregation of natamycin in the yeast plasma membrane. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, F.; Griffin, D.C.; Loraine, J.; Rittig, M.; Delves-Broughton, J.; Bonev, B.B. Recognition of Membrane Sterols by Polyene Antifungals Amphotericin B and Natamycin, A 13C MAS NMR Study. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.N.; Oliveira, S.S.C.; Magalhaes, L.B.; Neto, V.V.A.; Torres-Santos, E.C.; Carvalho, M.D.C.; Pereira, M.D.; Branquinha, M.H.; Santos, A.L.S. Unmasking the Amphotericin B Resistance Mechanisms in Candida haemulonii Species Complex. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shbeta, M.; Kopp, T.; Voronov, I.I.; Yona, A.; Afana, R.H.; Carmeli, S.; Fridman, S. Fluorescent Probes Derived from the Polyene Class of Antifungal Drugs Reveal Distinct Localization Patterns and Resistance-Associated Vacuolar Sequestration in Candida Species. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.E. The Role of Signaling via Aqueous Pore Formation in Resistance Responses to Amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5122–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, S.; De Lucca, A.J.; Boue, S.; Bland, J.M.; Vigo, C.B.; Selitrennikoff, C.P. CAY-I, a novel antifungal compound from cayenne pepper. Med. Mycol. 2003, 41, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.; Lakhani, P.; Taskar, P.; Avula, B.; Majumdar, S. Carboxyvinyl Polymer and Guar-Borate Gelling System Containing Natamycin Loaded PEGylated Nanolipid Carriers Exhibit Improved Ocular Pharmacokinetic Parameters. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. Off. J. Assoc. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 36, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhan, L.; Long, X.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luan, J.; Peng, X.; Zhao, G. Multifunctional natamycin modified chondroitin sulfate eye drops with anti-inflammatory, antifungal and tissue repair functions possess therapeutic effects on fungal keratitis in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janga, K.; Tatke, A.; Balguri, S.; Lamichanne, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Maria, D.; Jablonski, M.; Majumdar, S. Ion-sensitive in situ hydrogels of natamycin bilosomes for enhanced and prolonged ocular pharmacotherapy: In vitro permeability, cytotoxicity and in vivo evaluation. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desfrançois, C.; Auzely, R.; Texier, I. Lipid Nanoparticles and Their Hydrogel Composites for Drug Delivery. A Review. Pharm. Policy Law 2018, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Chauhan, I.; Kumar, G.; Tiwari, R.K. SmartLipids: Ushering in a New Era of Lipid Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Micro Nanosyst. 2024, 16, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, B.V.F.; Meneguin, A.B.; Baveloni, F.G.; de Antoni, J.A.; Robusti, L.M.G.; Gremião, M.P.D.; Ferrari, P.C.; Chorilli, M. Biopharmaceutical and Nanotoxicological Aspects of Cyclodextrins for Non-Invasive Topical Treatments: A Critical Review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, R.; Thorat, A.; Gargote, C. Current trends in β-cyclodextrin based drug delivery systems. Int. J. Res. Ayur. Pharm. 2011, 2, 1520–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Garnero, C.; Zoppi, A.; Aloisio, C.; Longhi, M.R. Technological Delivery Systems to Improve Biopharmaceutical Properties; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 253–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.-W.; Bahn, Y.S. The Stress-Activated Signaling (SAS) Pathways of a Human Fungal Pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycobiology 2009, 37, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.E.; Telzrow, C.L.; Saelens, J.W.; Fernandes, L.; Alspaugh, J.A. Sterol-Response Pathways Mediate Alkaline Survival in Diverse Fungi. mBio 2020, 11, e00719-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerdeira, C.D.; de Araújo, M.P.; Ferreira, C.B.R.J.; Dias, A.L.T.; Brigagão, M.R.P.L. Explorando os estresses oxidativo e nitrosativo contra fungos: Um mecanismo subjacente à ação de tradicionais antifúngicos e um potencial novo alvo terapêutico na busca por indutores oriundos de fontes naturais. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Químico-Farm. 2020, 50, 100–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radičević, T.; Janković, S.; Stefanović, S.; Nikolić, D.; Djinovic-Stojanovic, J.; Spirić, D.; Tanković, S. Determination of natamycin (food additive in cheese production) by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, M.; Grant, J.; Peterson, E. Trade impact of maximum residue limits in fresh fruits and vegetables. Food Policy 2022, 106, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Maximum Residue Limits and Agricultural Trade: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunoğlu, B.; Wilson, C.; Sağıroğlu, M.; Yüksel, S.; Şenel, S. Mucoadhesive bilayered buccal platform for antifungal drug delivery into the oral cavity. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 11, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinarov, Z.; Abdallah, M.; Agúndez, J.; Allegaert, K.; Basit, A.; Braeckmans, M.; Ceulemans, J.; Corsetti, M.; Griffin, B.; Grimm, M.; et al. Impact of gastrointestinal tract variability on oral drug absorption and pharmacokinetics: An UNGAP review. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. Off. J. Eur. Fed. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 162, 105812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, A.; Soutar, C.; Zhang, J.; Lewandowska, A.; Uno, B.; Yan, S.; Shelke, Y.; Murhade, G.; Nimerovsky, E.; Borcik, C.; et al. Tuning sterol extraction kinetics yields a renal-sparing polyene antifungal. Nature 2023, 623, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Maki, H.; Yoshida, O.; Hasegawa, Y.; Ukai, Y.; Fukushima, T. P-1115. COT-832, a Novel Polyene Macrolide Antifungal (II): In Vivo Fungicidal Efficacy against Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans in Mice and Rats Infection Models. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofae631.1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, A.; VanScoy, B.; Rubino, C.; Ambrose, P.; Andes, D. In vivo pharmacodynamic characterization of a next-generation polyene, SF001, in the invasive pulmonary aspergillosis mouse model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e0163123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, M.; Limon, J.; Bar, A.; Leal, C.; Gargus, M.; Tang, J.; Brown, J.; Funari, V.; Wang, H.; Crother, T.; et al. Immunological Consequences of Intestinal Fungal Dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelchuk, O.; Tevyashova, A.; Efimova, S.; Grammatikova, N.; Bychkova, E.; Zatonsky, G.; Dezhenkova, L.; Savin, N.; Solovieva, S.; Ostroumova, O.; et al. A Study on the Effect of Quaternization of Polyene Antibiotics’ Structures on Their Activity, Toxicity, and Impact on Membrane Models. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skwarecki, A.; Skarbek, K.; Martynow, D.; Serocki, M.; Bylińska, I.; Milewska, M.; Milewski, S. Molecular Umbrellas Modulate the Selective Toxicity of Polyene Macrolide Antifungals. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tevyashova, A.; Efimova, S.; Alexandrov, A.; Omelchuk, O.; Ghazy, E.; Bychkova, E.; Zatonsky, G.; Grammatikova, N.; Dezhenkova, L.; Solovieva, S.; et al. Semisynthetic Amides of Amphotericin B and Nystatin A1: A Comparative Study of In Vitro Activity/Toxicity Ratio in Relation to Selectivity to Ergosterol Membranes. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzyszkowska-Bukowska, J.; Górska, J.; Szczeblewski, P.; Laskowski, T.; Gabriel, I.; Jurasz, J.; Kozłowska-Tylingo, K.; Szweda, P.; Milewski, S. Quest for the Molecular Basis of Improved Selective Toxicity of All-Trans Isomers of Aromatic Heptaene Macrolide Antifungal Antibiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, A.; Hausammann, L.; Ceschi, A.; Kupferschmidt, H.; Weiler, S. Observational cross-sectional case study of toxicities of antifungal drugs. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 29, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.; Baumert, J.; Beyer, K.; Boyle, R.; Chan, C.; Clark, A.; Crevel, R.; DunnGalvin, A.; Fernández-Rivas, M.; Gowland, M.; et al. Can we identify patients at risk of life-threatening allergic reactions to food? Allergy 2016, 71, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedner, S.; Asarnoj, A.; Thulin, H.; Westman, M.; Konradsen, J.; Nilsson, C. Food allergy and hypersensitivity reactions in children and adults—A review. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 291, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalhoff, A.; Levy, S. Does use of the polyene natamycin as a food preservative jeopardise the clinical efficacy of amphotericin B? A word of concern. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomášová, E.; Závadová, M. Komplexe Sensitivität der Hefen und Schimmelpilze aus Sputum gegen Natamycin. Mycoses 2009, 16, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W. Toxicity of Natamycin and the Progress of Its Production and Study. J. Microbiol. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dalhoff, A. For Debate: May the Use of the Polyene Macrolide Natamycin as a Food Additive Foster Emergence of Polyene-Resistance in Candida Species? Clin. Microbiol. Open Access 2017, 6, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Rettedal, E.A.; van der Helm, E.; Ellabaan, M.; Panagiotou, G.; Sommer, M.O. Antibiotic Treatment Drives the Diversification of the Human Gut Resistome. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2019, 17, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.; Zhang, L.; Feil, E.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Snape, J.; Gaze, W.H.; Murray, A.K. Antimicrobial effects, and selection for AMR by non-antibiotic drugs on bacterial communities. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y. Oral Exposure to Epoxiconazole Disturbed the Gut Micro-Environment and Metabolic Profiling in Male Mice. Metabolites 2023, 13, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Effects of Antimicrobial Drug Residues from Food of Animal Origin on the Human Intestinal Flora. Prog. Vet. Med. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Corpet, D.E. Model Systems of Human Intestinal Flora, to Set Acceptable Daily Intakes of Antimicrobial Residues. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2000, 12, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, A.; Rocha, M.; Pereirinha, P.; Tomé, R.; Costa, E. Antifungals: From Pharmacokinetics to Clinical Practice. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolus, H.; Pierson, S.; Lagrou, K.; Van Dijck, P. Amphotericin B and Other Polyenes—Discovery, Clinical Use, Mode of Action and Drug Resistance. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.; Yadav, R.; Sanyam, S.; Chaudhary, P.; Roshan, A.; Singh, S.; Mishra, S.; Arunga, S.; Hu, V.; Macleod, D.; et al. Topical Chlorhexidine 0.2% versus Topical Natamycin 5% for the Treatment of Fungal Keratitis in Nepal. Ophthalmology 2021, 129, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajna, N.V.; Mascarenhas, J.; Krishnan, T.; Reddy, P.R.; Prajna, L.; Srinivasan, M.; Vaitilingam, C.M.; Hong, K.C.; Lee, S.M.; McLeod, S.D.; et al. Comparison of natamycin and voriconazole for the treatment of fungal keratitis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Zhao, G.-Q.; Lin, J.; Wang, X.; Hu, L.-T.; Du, Z.-D.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, C.-C. Natamycin in the treatment of fungal keratitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 8, 597. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, E.M.; Ram, F.S.; Patel, D.V.; McGhee, C.N. Effectiveness of topical antifungal drugs in the management of fungal keratitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 3, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nabarawi, M.A.; Abd El Rehem, R.T.; Teaima, M.; Abary, M.; El-Mofty, H.M.; Khafagy, M.M.; Salah, M. Natamycin niosomes as a promising ocular nanosized delivery system with ketorolac tromethamine for dual effects for treatment of candida rabbit keratitis; in vitro/in vivo and histopathological studies. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2019, 45, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.Q.; Lalitha, P.; Prajna, N.V.; Karpagam, R.; Geetha, M.; O’Brien, K.S.; Oldenburg, C.E.; Ray, K.J.; McLeod, S.D.; Acharya, N.R.; et al. Association between in vitro susceptibility to natamycin and voriconazole and clinical outcomes in fungal keratitis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, P.A. Fungal infections of the cornea. Eye 2003, 17, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janga, K.; Tatke, A.; Dudhipala, N.; Balguri, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Maria, D.; Jablonski, M.; Majumdar, S. Gellan Gum Based Sol-to-Gel Transforming System of Natamycin Transfersomes Improves Topical Ocular Delivery. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 370, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Guan, X.; Ma, J.; Ding, D.; Zhang, W. Fabrication and Characterization of Chitosan/Poly(Lactic-Co-glycolic Acid) Core-Shell Nanoparticles by Coaxial Electrospray Technology for Dual Delivery of Natamycin and Clotrimazole. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 635485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Das, S.; Virdi, A.; Fernandes, M.; Sahu, S.; Koday, N.; Ali, M.; Garg, P.; Motukupally, S. Re-appraisal of topical 1% voriconazole and 5% natamycin in the treatment of fungal keratitis in a randomised trial. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 99, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluja, G.; Sharma, N.; Agarwal, R.; Sharma, H.; Singhal, D.; Maharana, P.; Sinha, R.; Agarwal, T.; Velpandian, T.; Titiyal, J.; et al. Comparison of Safety and Efficacy of Intrastromal Injections of Voriconazole, Amphotericin B and Natamycin in Cases of Recalcitrant Fungal Keratitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 15, 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Tomé, V.; Bendicho-Lavilla, C.; García-Otero, X.; Varela-Fernández, R.; Martín-Pastor, M.; Llovo-Taboada, J.; Alonso-Alonso, P.; Aguiar, P.; González-Barcia, M.; Fernández-Ferreiro, A.; et al. Antifungal Combination Eye Drops for Fungal Keratitis Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Yang, C.; Wei, Q.; Lian, H.; An, L.; Zhang, R. Natamycin versus natamycin combined with voriconazole in the treatment of fungal keratitis. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 39, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, P.; Patil, A.; Majumdar, S. Challenges in the Polyene- and Azole-Based Pharmacotherapy of Ocular Fungal Infections. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. Off. J. Assoc. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 35, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragona, P.; Baudouin, C.; Del Castillo, J.; Messmer, E.; Barabino, S.; Merayo-Lloves, J.; Brignole-Baudouin, F.; Inferrera, L.; Rolando, M.; Mencucci, R.; et al. The Ocular Microbiome and Microbiota and their Effects on Ocular Surface Pathophysiology and Disorders. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2021, 66, 907–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Diebold, Y.; Sahu, S.; Leonardi, A. Epithelial barrier dysfunction in ocular allergy. Allergy 2021, 77, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argüeso, P.; Woodward, A.; Abusamra, D. The Epithelial Cell Glycocalyx in Ocular Surface Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 729260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazu, V.; Moros, M.; Sánchez-Espinel, C. Nanocarriers as nanomedicines: Design concepts and recent advances. Front. Nanosci. 2012, 4, 337–440. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, D.; Modi, A.; Ghosh, R.; Benito-León, J. Drug delivery and functional nanoparticles. In Antiviral and Antimicrobial Coatings Based on Functionalized Nanomaterials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 447–484. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.; Peng, T.; Mi, C.; Ye, L. Editorial: Micro-nano-materials for drug delivery, disease diagnosis, and therapeutic treatment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1645112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Sinha, V.R.; Kaur, R. Clinical Considerations on Micro- and Nanodrug Delivery Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, M.; Dhakne, R.; Dehghan, M.H.G. Ocular delivery of natamycin based on monoolein/span 80/poloxamer 407 nanocarriers for the effectual treatment of fungal keratitis. J. Res. Pharm. 2020, 24, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.A.A.; Dudhipala, N.; Majumdar, S. Dual Drug Loaded Lipid Nanocarrier Formulations for Topical Ocular Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 2283–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, E.B.; Martins-Lopes, P.; Martins-Lopes, C.; Gaivão, I.; Silva, A.M.; Guedes-Pinto, H. A note on regulatory concerns and toxicity assessment in lipid-based delivery systems (LDS). J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2009, 5, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, M.; Kaur, A.; Kumar, R. Challenges in utilizing diethylene glycol and ethylene glycol as excipient: A thorough overview. Pharmaspire 2023, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarvarty, G. Nanoparticles & Nanotechnology: Clinical, Toxicological, Social, Regulatory & other aspects of Nanotechnology. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2013, 3, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Savita, K.K.; Dubey, A.; Gaur, S.S. Unlocking Dithranol’s Potential: Advanced Drug Delivery Systems for Improved Pharmacokinetics. Int. J. Drug Deliv. Technol. 2024, 14, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.; Hornig, M.; Lozupone, C.A.; Debelius, J.W.; Gilbert, J.A.; Knight, R. Towards large-cohort comparative studies to define the factors influencing the gut microbial community structure of ASD patients. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 26555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.L.; Raulo, A.; Knowles, S.C.L. Identifying Microbiome-Mediated Behaviour in Wild Vertebrates. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020, 35, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzo, A.; Brown, J.R. The Microbiome Factor in Drug Discovery and Development. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaas, N.F.; Haba, M.K. Histopathological Changes caused by The Chronic Effect of Nitrofurantoin Drug in The Testes of Albino Mice. Baghdad Sci. J. 2015, 12, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertlake, P.T.; Hil, G.J.; Butler, W.T. Renal histopathology associated with different degrees of amphotericin b toxicity in the dog. Exp. Biol. Med. 1965, 118, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, I.; Ali, I.; El-Sherbiny, I. Noninvasive biodegradable nanoparticles-in-nanofibers single-dose ocular insert: In vitro, ex vivo and in vivo evaluation. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirampour, N.; Bustos-Salgado, P.; Garrós, N.; Mohammadi-Meyabadi, R.; Domènech, Ò.; Suñer-Carbó, J.; Rodríguez-Lagunas, M.; Kapravelou, G.; Montes, M.; Calpena, A.; et al. Formulation of Polymeric Nanoparticles Loading Baricitinib as a Topical Approach in Ocular Application. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameeduzzafar Ali, J.; Fazil, M.; Qumbar, M.; Khan, N.; Ali, A. Colloidal drug delivery system: Amplify the ocular delivery. Drug Deliv. 2014, 23, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Lu, A.; Gong, J.; Yang, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, M.; Xu, H. Nanoparticles in ocular applications and their potential toxicity. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 931759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, N.; Qian, J.; Hu, L.; Huang, P.; Su, M.; Yu, X.; Fu, C.; Jiang, F.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Urinary Antibiotics of Pregnant Women in Eastern China and Cumulative Health Risk Assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 3518–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Jian, Z.; Li, P.; Jin, X.; Li, H.; Wang, K. Association between antibiotic exposure and adverse outcomes of children and pregnant women: Evidence from an umbrella review. World J. Pediatr. 2023, 19, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Jin, L.; Li, Z.; Ren, A.; Wang, L. Inadvertent antibiotic exposure during pregnancy may increase the risk for neural tube defects in offspring. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 275, 116271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Masoomi, A.; Ahmadikia, K.; Tabatabaei, S.A.; Soleimani, M.; Rezaie, S.; Ghahvechian, H.; Banafsheafshan, A. Fungal keratitis: An overview of clinical and laboratory aspects. Mycoses 2018, 61, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Riduan, S.N.; Ying, J.Y.; Zhang, Y. Short imidazolium chains effectively clear fungal biofilm in keratitis treatment. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Romani, L.; Netea, M.G.; Latgé, J.P. Aspergillus fumigatus morphology and dynamic host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banshoya, K.; Fujita, C.; Hokimoto, Y.; Ohnishi, M.; Inoue, A.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneo, Y. Amphotericin B nanohydrogel ocular formulation using alkyl glyceryl hyaluronic acid: Formulation, characterization, and in vitro evaluation. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 610, 121061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Xu, H.; Wei, J.; Niu, L.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, C. Bacteria-Targeting Nanoparticles with ROS-Responsive Antibiotic Release to Eradicate Biofilms and Drug-Resistant Bacteria in Endophthalmitis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 2939–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Li, C.; Lin, J.; Wang, Q.; Yin, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, N.; Lin, H.; You, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Drug-loaded mesoporous carbon with sustained drug release capacity and enhanced antifungal activity to treat fungal keratitis. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 136, 212771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Yuan, J.; Mo, F.; Wu, S.; Ma, Y.; Li, R.; Li, M. A pH-Responsive Essential Oil Delivery System Based on Metal-organic Framework (ZIF-8) for Preventing Fungal Disease. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 18312–18322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Sarrafpour, S.; Teng, C.C.; Liu, J. External Disruption of Ocular Development in Utero. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2024, 97, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.Y.; Kwok, A.K.H.; Chung, K.L. Use of ophthalmic medications during pregnancy. Hong Kong Med. J. 2004, 10, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Boule, L.A.; Lawrence, B.P. Influence of Early-Life Environmental Exposures on Immune Function Across the Life Span; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2016; pp. 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauta, A.J.; Garssen, J. Nutritional Programming of Immune Defense Against Infections in Early Life; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.J.; Winn, B.J. Perturbations of the ocular surface microbiome and their effect on host immune function. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 34, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezbaeva, G.N.; Orenburkina, O.I.; Gimranova, I.A.; Babushkin, A.; Gazizullina, G.R. The normal microbiota of the ocular surface and the connection between the changes in its composition and ophthalmic pathologies. Russ. Ophthalmol. J. 2024, 17, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qiu, P.; Shen, T. Gut microbiota and eye diseases: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, 39866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharova, I.N.; Berezhnaya, I.V.; Dmitrieva, D.K.; Pupykina, V.V. Axis ”microbiota–gut–eye”: A review. Pediatr. Consilium Medicum 2024, 2, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterweger, H.; Janko, C.; Civelek, M.; Cicha, I.; Spielvogel, H.; Tietze, R.; Friedrich, B.; Alexiou, C. Nanomaterial-based ophthalmic therapies. Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindod, H.V.; Hatwar, P.R.; Bakal, R.L. Innovative ocular drug delivery systems: A comprehensive review of nano formulations and future directions. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 29, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, P.B.; Koilpillai, J.; Narayanasamy, D. Advancing Ocular Medication Delivery with Nano-Engineered Solutions: A Comprehensive Review of Innovations, Obstacles, and Clinical Impact. Cureus 2024, 16, e66476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameshwar, K.; Samal, H.B. Nano Carrier-Mediated Ocular Therapeutic Delivery: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Nanomed. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, S.; Paliwal, R.; Paliwal, S.R.; Vyas, S.P. Nanocarriers in Ocular Drug Delivery: An Update Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 2724–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandyala, S.; Borse, L.B.; Yedke, N.G.; Alluri, P.G.; Babu, M.S. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) as an Animal Model for Preclinical Research: A Comprehensive Review. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool. 2025, 46, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, C.D.; Siebel, A.M. Zebrafish as a model for pharmacological and toxicological research. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 976970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavić, A.; Stojanović, Z.; Pekmezović, M.; Veljović, Đ.; O’Connor, K.; Malagurski, I.; Nikodinović-Runić, J. Polyenes in Medium Chain Length Polyhydroxyalkanoate (mcl-PHA) Biopolymer Microspheres with Reduced Toxicity and Improved Therapeutic Effect against Candida Infection in Zebrafish Model. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaković, N.; Nikolić, A.; Jovanović, N.; Stojković, P.; Stankovic, N.; Šolaja, B.; Opsenica, I.; Pavić, A. Unraveling the anti-virulence potential and antifungal efficacy of 5-aminotetrazoles using the zebrafish model of disseminated candidiasis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 230, 114137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulatunga, D.; Dananjaya, S.; Nikapitiya, C.; Kim, C.; Lee, J.; De Zoysa, M. Candida albicans Infection Model in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) for Screening Anticandidal Drugs. Mycopathologia 2019, 184, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel-Magalhães, M.; Medeiros, R.; Guedes, N.; De Brito, T.; De Souza, G.; Canabarro, B.; Ferraris, F.; Amendoeira, F.; Rocha, H.; Patricio, B.; et al. Amphotericin B Encapsulation in Polymeric Nanoparticles: Toxicity Insights via Cells and Zebrafish Embryo Testing. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Luo, T.; Zhu, Z.; Pan, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Fu, Z.; Jin, Y. Imazalil exposure induces gut microbiota dysbiosis and hepatic metabolism disorder in zebrafish. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 202, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, C.; Lai, N.; Zhang, W.; Hua, J.; Lam, P.; Lam, J.; Zhou, B. Acute exposure to PBDEs at an environmentally realistic concentration causes abrupt changes in the gut microbiota and host health of zebrafish. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, M.; Yu, K.; Qiu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Gao, C.; Feng, R.; Zeng, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.; Su, H. Environmental concentrations of antibiotics alter the zebrafish gut microbiome structure and potential functions. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 278, 116760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Wang, J.; Ji, X.; Yang, H.; Tang, B.; Zhang, H.; Yang, G.; Bao, Z.; Jin, Y. Sub-chronic exposure to antibiotics doxycycline, oxytetracycline or florfenicol impacts gut barrier and induces gut microbiota dysbiosis in adult zebrafish (Daino rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 221, 112464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, S.; Dunn, C.; Ramos, M. Zebrafish as an Animal Model for Ocular Toxicity Testing: A Review of Ocular Anatomy and Functional Assays. Toxicol. Pathol. 2020, 49, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Lin, Z.; Qi, Z.; Cai, Z.; Chen, Z. Effects of pollutant toxicity on the eyes of aquatic life monitored by visual dysfunction in zebrafish: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 21, 1177–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Ma, Y.; Ma, J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, K.; Jin, L.; Yang, Q.; Sun, D.; Wu, D. Rapid Assessment of Ocular Toxicity from Environmental Contaminants Based on Visually Mediated Zebrafish Behavior Studies. Toxics 2023, 11, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Lima, C. An Overview towards Zebrafish Larvae as a Model for Ocular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Pu, M.; Jiang, K.; Qiu, W.; Xu, E.; Wang, J.; Magnuson, J.; Zheng, C. Maternal or Paternal Antibiotics? Intergenerational Transmission and Reproductive Toxicity in Zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, F.; Li, R.; Xiong, Y.; Fu, C.; Li, G.; Liu, S.; Zheng, C. Single and joint toxic effects of four antibiotics on some metabolic pathways of zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 137062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.Y.; Yao, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, C. In vivo and in silico evaluations of survival and cardiac developmental toxicity of quinolone antibiotics in zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio). Environ. Pollut. 2021, 277, 116779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Huang, X.; Xie, Y.; Song, M.; Zhu, K.; Ding, S. Macrolides induce severe cardiotoxicity and developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Teng, M.; Tian, S.; Yan, J.; Meng, Z.; Yan, S.; Li, R.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, W. Developmental toxicity and neurotoxicity of penconazole enantiomers exposure on zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, L.; Liang, H. Enantioselective bioaccumulation and toxicity of the novel chiral antifungal agrochemical penthiopyrad in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 113010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.; Siddiqui, H.; Riguene, E.; Nomikos, M. Zebrafish: A Versatile and Powerful Model for Biomedical Research. BioEssays 2025, 47, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, S.; Fischer, S.; Gündel, U.; Küster, E.; Luckenbach, T.; Voelker, D. The zebrafish embryo model in environmental risk assessment—Applications beyond acute toxicity testing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2008, 15, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, W.-P.; Pei, D.-S. Zebrafish Model for Safety and Toxicity Testing of Nutraceuticals. In Nutraceuticals; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonich, M.T.; Franzosa, J.A.; Tanguay, R.L. In Vivo Approaches to Predictive Toxicology Using Zebrafish. In New Horizons in Predictive Toxicology; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2011; Chapter 14; pp. 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Anselmo, C.; Sardela, V.F.; de Sousa, V.P.; Pereira, H.M.G. Zebrafish (Danio rerio): A valuable tool for predicting the metabolism of xenobiotics in humans? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 212, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderton, W.; Berghmans, S.; Butler, P.; Chassaing, H.; Fleming, A.; Golder, Z.; Richards, F.; Gardner, I. Accumulation and metabolism of drugs and CYP probe substrates in zebrafish larvae. Xenobiotica 2010, 40, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, K.L.; Wang, X.; Ng, A.S.; Goh, W.H.; McGinnis, C.; Fowler, S.; Carney, T.J.; Wang, H.; Ingham, P.W. Humanizing the zebrafish liver shifts drug metabolic profiles and improves pharmacokinetics of CYP3A4 substrates. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chng, H.T.; Ho, H.K.; Yap, C.W.; Lam, S.H.; Chan, E.C.Y. An investigation of the bioactivation potential and metabolism profile of zebrafish versus human. J. Biomol. Screen. 2012, 17, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukardi, H.; Chng, H.T.; Chan, E.C.Y.; Gong, Z.; Lam, S.H. Zebrafish for drug toxicity screening: Bridging the in vitro cell-based models and in vivo mammalian models. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2011, 7, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tal, T.; Yaghoobi, B.; Lein, P. Translational Toxicology in Zebrafish. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2020, 23–24, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshead, M.; Tanguay, R. Advancements in the Developmental Zebrafish Model for Predictive Human Toxicology. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2024, 41, 100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catron, T.R.; Keely, S.P.; Brinkman, N.E.; Zurlinden, T.J.; Wood, C.E.; Wright, J.R.; Phelps, D.; Wheaton, E.; Kvasnicka, A.; Gaballah, S.; et al. Host developmental toxicity of BPA and BPA alternatives is inversely related to microbiota disruption in zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 167, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Eswar, K.; Ramesh, S.S.R.; Prajapati, A.; Sonpipare, T.; Basa, A.; Gubige, M.; Ponnapalli, S.; Thatikonda, S.; Rengan, A.K. Zebrafish as a versatile model organism: From tanks to treatment. MedComm Future Med. 2025, 4, e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Zhu, W.; Wang, D.; Qi, S.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Dong, K.; Zheng, M.; Wang, C. Metabolomics and transcriptomics reveal the toxicity of difenoconazole to the early life stages of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 194, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Villanueva, E.; Navarro-Martín, L.; Jaumot, J.; Benavente, F.; Sanz-Nebot, V.; Piña, B.; Tauler, R. Metabolic disruption of zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos by bisphenol A. An integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic approach. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Gong, Z.; Tse, W. Zebrafish as the toxicant screening model: Transgenic and omics approaches. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 234, 105813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Pan, Y.; Yang, L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, X.; Chang, J.; Hao, W.; Zhu, L.; Wan, B. Developmental toxicity of TCBPA on the nervous and cardiovascular systems of zebrafish (Danio rerio): A combination of transcriptomic and metabolomics. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 127, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Sung, E.; Seo, S.; Min, E.; Lee, J.; Shim, I.; Kim, P.; Kim, T.; Lee, S.; Kim, K. Integrated multi-omics analysis reveals the underlying molecular mechanism for developmental neurotoxicity of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid in zebrafish. Environ. Int. 2021, 157, 106802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Tian, S.; Gu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Meng, Z. Toxicity effects of pesticides based on zebrafish (Danio rerio) models: Advances and perspectives. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.; Cowan, C.; Bastiaanssen, T.; Moloney, G.; Theune, N.; Wouw, M.; Zanuy, E.; Ventura-Silva, A.; Codagnone, M.; Villalobos-Manríquez, F.; et al. Critical windows of early-life microbiota disruption on behaviour, neuroimmune function, and neurodevelopment. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 108, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, E.; Ullah, A.; Aldejohann, A.; Kurzai, O.; Janevska, S.; Walther, G. In vitro activity of novel antifungals, natamycin, and terbinafine against Fusarium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0191324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Xu, X.; Zhou, M.; Liang, Q.; Lu, X. Antifungal susceptibility and clinical efficacy of chlorhexidine combined with topical ophthalmic medications against Fusarium species isolated from corneal samples. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1532289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Sui, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Peng, X.; Meng, F.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, N.; Zhao, G.; Lin, J. The Preparation and Therapeutic Effects of β-Glucan-Specific Nanobodies and Nanobody-Natamycin Conjugates in Fungal Keratiti. Acta Biomater. 2023, 169, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ververis, E.; Ackerl, R.; Azzollini, D.; Colombo, P.; De Sesmaisons, A.; Dumas, C.; Fernández-Dumont, A.; Da Costa, L.; Germini, A.; Goumperis, T.; et al. Novel foods in the European Union: Scientific requirements and challenges of the risk assessment process by the European Food Safety Authority. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, H.; Alonso-Andicoberry, C.; Assunção, R.; Cavaliere, F.; Eneroth, H.; Hoekstra, J.; Koulouris, S.; Kouroumalis, A.; Lorenzetti, S.; Mantovani, A.; et al. Risk-benefit in food safety and nutrition–Outcome of the 2019 Parma Summer School. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallocca, G.; Moné, M.; Kamp, H.; Luijten, M.; Van De Water, B.; Leist, M. Next-generation risk assessment of chemicals—Rolling out a human-centric testing strategy to drive 3R implementation: The RISK-HUNT3R project perspective. Altex 2022, 39, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devos, Y.; Elliott, K.; Macdonald, P.; McComas, K.; Parrino, L.; Vrbos, D.; Robinson, T.; Spiegelhalter, D.; Gallani, B. Conducting fit-for-purpose food safety risk assessments. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e170707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Országh, E.; De Matteu Monteiro, C.; Pires, S.; Jóźwiak, Á.; Marette, S.; Membré, J.; Feliciano, R. Holistic risk assessments of food systems. Glob. Food Secur. 2024, 43, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, A. Drug Metabolism and Toxicological Mechanisms. Toxics 2025, 13, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Kushwah, H.; Ranjan, O.P. Drug repurposing in cancer therapy. In Drug Repurposing: Innovative Approaches to Drug Discovery and Development; Chella, N., Ranjan, O.P., Alexander, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 57–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugescu, L.; Yang, Y.; Kool, J.F.; Fyhrquist, N.; Wincent, E.; Alenius, H. Microbiota modulates compound-specific toxicity of environmental chemicals: A multi-omics analysis in zebrafish embryos. Environ. Int. 2025, 188, 109828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zupanic, A.; Talikka, M.; Belcastro, V.; Madan, S.; Dörpinghaus, J.; Berg, C.V.; Szostak, J.; Martin, F.; Peitsch, M.C.; et al. Systems Toxicology Approach for Testing Chemical Cardiotoxicity in Larval Zebrafish. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33, 2550–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Brito, R.; Pereira, A.; Farias, D.; Rocha, T. Transgenic zebrafish (Danio rerio) as an emerging model system in ecotoxicology and toxicology: Historical review, recent advances, and trends. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Ban, Z. Gliadin Nanoparticles Stabilized by Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose as Carriers for Improved Dispersibility, Stability and Bacteriostatic Activity of Natamycin. SSRN Electron. J. 2023, 53, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, M.; Naeem, M.; Aly-Aldin, M. Enhancing the bioavailability and antioxidant activity of natamycin E235-ferulic acid loaded polyethylene glycol/carboxy methyl cellulose films as anti-microbial packaging for food application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Song, X.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Feng, J.Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Study on the Antifungal Activity and Potential Mechanism of Natamycin against Colletotrichum fructicola. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17713–17722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yu, C.; Gou, C.; Yan, X. Antimicrobial activity enabled by chitosan-ε-polylysine-natamycin and its effect on microbial diversity of tomato scrambled egg paste. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound/Study | Species/Model | Route of Administration | Dose/Concentration | Duration | Endpoints/Outcomes Assessed | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natamycin (semisynthetic amides) | Mice, human cell lines | intravenous injection, invitro (cell culture medium) | Not specified (in vivo); MICs in vitro | Acute (in vivo), short-term (in vitro) | LD50/ED50 ratio, cytotoxicity, antiproliferative activity, antifungal efficacy | [12] |

| Natamycin (nanoparticle delivery) | Mice, in vitro | Ocular (topical) | Not specified | Short-term | Cytotoxicity, ocular tolerance, systemic safety, anti-inflammatory effects | [13] |

| Amphotericin B, Nystatin | Human, animal, in vitro | Parenteral (AmB), oral/topical (Nys) | 3–4 mg/kg/day (AmB liposomal) | Variable | Nephrotoxicity, hemolytic toxicity, antifungal efficacy, resistance | [48,64,65] |

| Category | Study/Key Details | Design/Context | Outcomes/Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial | Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial I | Randomized, double-masked, multicenter (n = 120) | No significant difference vs. voriconazole in visual acuity at 3 months (p = 0.29); similar perforation rates (9/60 vs. 10/60) | [67] |

| Clinical Trial | Systematic Review & Meta-analysis | 7 RCTs, 804 participants; comparison with econazole, chlorhexidine, voriconazole, fluconazole | Better outcomes vs. voriconazole (−0.18 logMAR; p = 0.006); especially superior in Fusarium cases (−0.41 logMAR; p < 0.001) | [68] |

| Clinical Trial | Cochrane Meta-analysis | 8 RCTs, 793 participants; overall treatment effectiveness | Improved visual acuity vs. voriconazole (WMD 0.13); lower keratoplasty risk (RR 1.89 for voriconazole) | [69] |

| Preclinical Study | Niosomal Delivery System | In vitro/in vivo rabbit model; natamycin-loaded niosomes with ketorolac gel | 96.43% entrapment; prolonged release (40.96–77.49% over 24 h); enhanced corneal penetration | [70] |

| Preclinical Study | Susceptibility Analysis | MIC testing on trial isolates (n = 221) | Higher natamycin MIC correlated with increased scar size (+0.29 mm) and higher perforation risk (OR 2.41) | [71] |

| Preclinical/Review | Drug Development Review | Review of formulation limits and bioavailability | <5% bioavailability; molecular mass > 500 Da restricts penetration; need for advanced delivery systems | [3] |

| Overall Significance | FDA Approval Status | Clinical importance | Only FDA-approved topical antifungal for fungal keratitis | [3] |

| Overall Significance | Preferred Drug for Filamentous Fungi | Clinical importance | Most effective for filamentous fungi, especially Fusarium | [72] |

| Overall Significance | Safety Profile | Clinical importance | Excellent safety with fewer adverse effects | [3] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bangeppagari, M.; Jagadish, P.; Srinivasa, A.; Choi, W.; Tiwari, P. Natamycin in Food and Ophthalmology: Knowledge Gaps and Emerging Insights from Zebrafish Models. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010086

Bangeppagari M, Jagadish P, Srinivasa A, Choi W, Tiwari P. Natamycin in Food and Ophthalmology: Knowledge Gaps and Emerging Insights from Zebrafish Models. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleBangeppagari, Manjunatha, Pavana Jagadish, Anusha Srinivasa, Woorak Choi, and Pragya Tiwari. 2026. "Natamycin in Food and Ophthalmology: Knowledge Gaps and Emerging Insights from Zebrafish Models" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010086

APA StyleBangeppagari, M., Jagadish, P., Srinivasa, A., Choi, W., & Tiwari, P. (2026). Natamycin in Food and Ophthalmology: Knowledge Gaps and Emerging Insights from Zebrafish Models. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010086