Herbal and Natural Products for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies Focusing on Molecular Microbiome and Barrier Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

- -

- antibiotic-associated diarrhea

- -

- antibiotic-induced dysbiosis

- -

- herbal medicine

- -

- natural product

- -

- polysaccharide

- -

- specific herbal agents

- -

- gut microbiota

- -

- microbiome

- -

- 16S rRNA

- -

- animal model

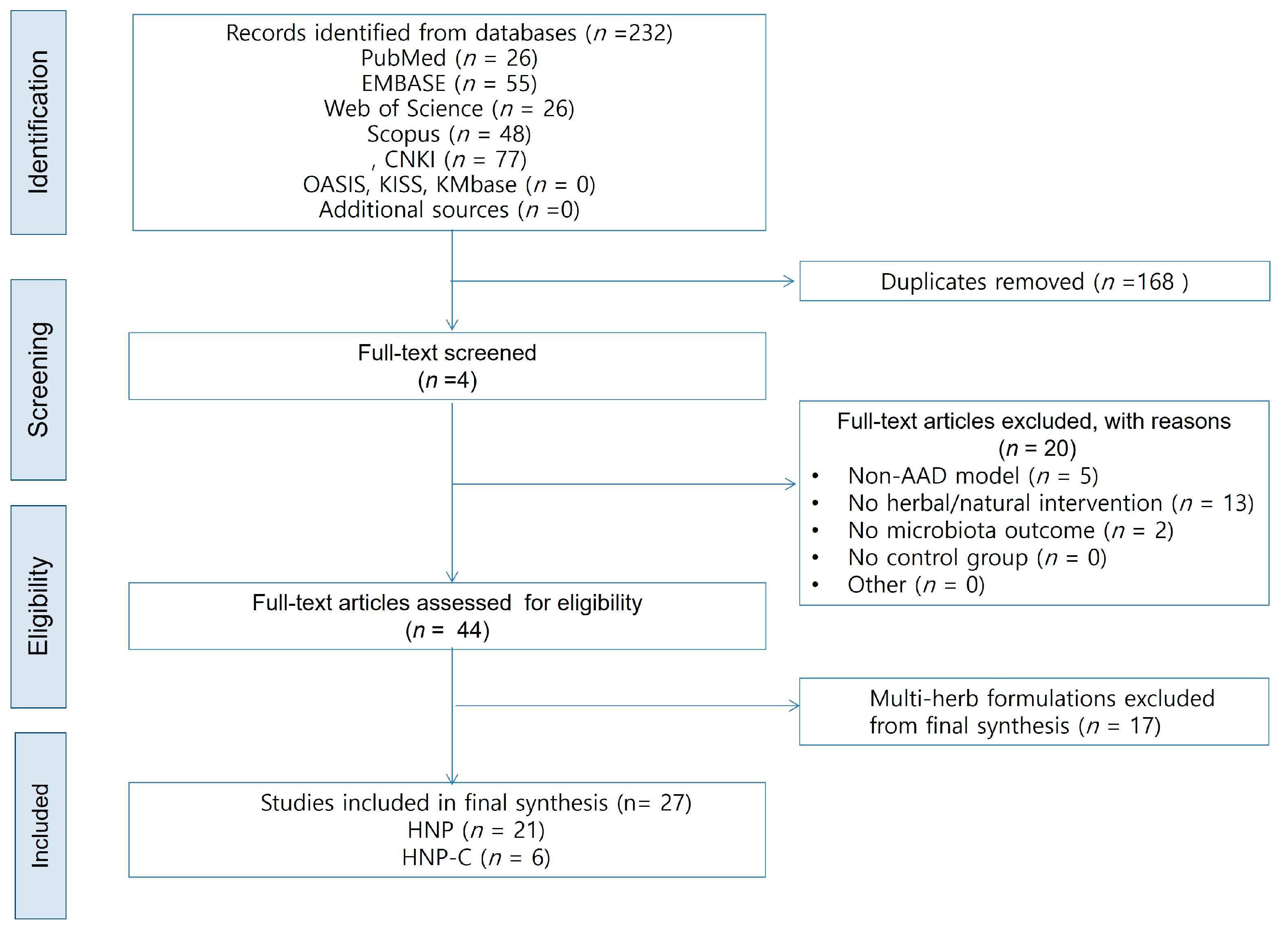

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Microbial Diversity and Composition (Table 2 and Table 3)

3.3.1. Effects on α-Diversity

3.3.2. Effects on β-Diversity

3.3.3. Key Taxonomic Shifts

| Group | Study ID | Intervention (Short) | α-Diversity Effect | β-Diversity Effect | Key Taxa Changes | SCFA | Barrier Markers | Immune and Inflammatory Markers | Histopathology | Mechanistic Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNP | Xu et al. [25] | Tangeretin (Citrus flavonoid) | ↑ Diversity (recovery trend) | PCoA shifted toward NC | ↑ Lachnospiraceae, Bacteroidaceae; ↓ Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonadaceae | Acetate, isobutyrate, butyrate, valerate ↑ | Not measured (in vitro model) | Anti-inflammatory trend inferred from SCFA ↑ & pathogen suppression | Not performed | Tangeretin restored diversity and SCFAs, enriched beneficial taxa, and reduced opportunistic pathogens |

| HNP | Ren et al. [26] | American ginseng polysaccharide | Shannon ↑ (close to NC) | PCoA shifted toward NC | ↑ Bacteroidetes; ↓ Firmicutes, Proteobacteria | Not reported | Colon structure repaired (↑ villus length, goblet cells) | Not reported | Villus and goblet cell morphology improved; edema reduced. | American ginseng polysaccharide alleviated dysbiosis and promoted mucosal repair via microbiota modulation. |

| HNP | Min, et al. [27] | Korean red ginseng polysaccharide | Diversity indices ↑ | PCoA approached NC | ↑ Firmicutes, ↓ Proteobacteria | Acetate and butyrate ↑ | Lysozyme, claudin-1 ↑ | Fecal IgA ↑ | – | Red ginseng polysaccharide rebalanced microbiota, enhanced SCFA, and reinforced barrier and mucosal immune homeostasis. |

| HNP | Qi et al. [28] | Neutral ginseng polysaccharide | Shannon and Chao1 ↑ | PCoA partially restored toward NC | ↑ Lactobacillus; ↓ Bacteroides, Pseudomonas | Not measured | Histologic repair (villus structure) | Not reported | Villus atrophy and goblet cell loss reversed. | Neutral ginseng polysaccharide increased beneficial flora and reduced pathogens, restoring diversity and mucosal structure. |

| HNP | Pan et al. [29] | Dioscorea sulfated polysaccharide | Not reported (DGGE only) | UPGMA: closer to NC | ↑ Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron; ↓ Enterococcus, Acinetobacter | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not performed | Sulfated yam polysaccharide restored microbial balance and alleviated diarrhea via reduction in pathogens and enrichment of commensals. |

| HNP | Li S, et al. [30] | Astragalus polysaccharide | Shannon and Chao1 ↑ | NMDS: closer to NC | ↑ Oscillospira, Dorea; ↓ Epulopiscium, Pseudomonas | Propionate, butyrate, total SCFAs ↑ | Colon architecture normalized | Inflammatory cell infiltration ↓ | Normal mucosal architecture restored. | Astragalus polysaccharide modulated microbiota and selectively enhanced propionate and butyrate generation. |

| HNP | Xu et al. [31] | Poria cocos polysaccharide | Richness and diversity ↑ | PCoA: closer to NC | ↑ Parabacteroides distasonis, Akkermansia muciniphila; ↓ Salmonella, Mucispirillum | Predicted ↑ carbohydrate metabolism; SCFA receptors (GPR41/43) ↑ | ZO-1, OC-1 ↑ | FOXP3 mRNA ↑, NF-κB ↓ | Mucosal damage reversed; villus and goblet cells normalized. | Poria polysaccharide restored microbial diversity and tight junctions, activated FOXP3 and SCFA receptor pathways, and suppressed NF-κB. |

| HNP | Lai et al. [32] | Dictyophora polysaccharide | Shannon and ACE ↑ | PCoA/type analysis: DIPY shifted toward NC | ↑ Robinsoniella, Parasutterella, Blautia; ↓ some Muribaculaceae | Acetate and total SCFAs ↑ | Epithelial integrity and mucus layer restored | LPS, MCP-1, TNF-α, IL-6 ↓ | Intact epithelium with restored goblet cells. | Dictyophora polysaccharide modulated microbiota, enhanced SCFA production, repaired barrier, and reduced systemic inflammation. |

| HNP | Bie et al. [33] | Sweet potato polysaccharide | Chao and Shannon ↑ | PCoA: shifted toward NC | ↓ Proteobacteria; ↑ Bacteroidetes, Muribaculaceae; ↓ Escherichia coli, Klebsiella | Acetate, propionate, butyrate, valerate, total SCFAs ↑ | Ileal villus length and crypt depth restored | IL-10 ↑; IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α ↓ | Reduced inflammatory infiltration; improved ileal morphology. | Sweet potato polysaccharide reversed dysbiosis, enhanced SCFA production, and regulated IL-10–mediated anti-inflammatory pathways. |

| HNP | Zhang et al. [34] | Yam extract | DGGE: richness/evenness ↑ | UPGMA/PCA: re-clustering toward NC | ↑ Bacteroides spp., Clostridium spp.; ↓ Enterobacter spp. | Propionate, butyrate, valerate, total SCFAs ↑ | Cecal index normalized (indirect barrier recovery) | Not assessed | Cecal enlargement reversed. | Yam extract acted as substrate for SCFA-producing bacteria, enhancing SCFA production and gut recovery. |

| HNP | Pan et al. [35] | Brown alga polysaccharide (Nemacystus) | Indices restored toward NC | PCoA: cluster closer to NC | ↓ Proteobacteria; ↑ Muribaculum, Lactobacillus; ↓ Enterobacter, Clostridioides | SCFA-producing genera recovered (not quantified) | Occludin and SHIP ↑ | IL-1β, IL-6, p-PI3K, p-NF-κB ↓ | Smoother mucosa; reduced inflammatory infiltration. | Brown alga polysaccharide enhanced commensals, maintained tight junctions via SHIP–PI3K/NF-κB modulation, and suppressed inflammation. |

| HNP | Lai et al. [36] | Poria cocos water-insoluble polysaccharide | Simpson, ACE, Shannon ↑ | PCoA: closer to NC | ↑ norank_f__Muribaculaceae; ↓ Staphylococcus, Acinetobacter, Escherichia–Shigella | Acetate, butyrate ↑ | Cecal mucosa continuity restored | Serum TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β ↓ | Almost normal architecture. | Water-insoluble Poria polysaccharide remodeled microbiota, increased SCFAs, reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines, and repaired barrier. |

| HNP | Lu et al. [37] | Antrodia cinnamomea intracellular polysaccharide | Shannon ↑, Simpson ↓ (diversity restored) | PCoA/NMDS: closer to NC | ↑ Erysipelotrichaceae, Lachnospiraceae; ↓ Enterococcus | Not measured | Thymus and spleen index restored | Serum IL-6, TNF-α ↓ | Colon structure improved. | Antrodia polysaccharide reduced pathogenic Enterococcus, enhanced butyrate-producing commensals, and improved immune-organ indices. |

| HNP | Cui et al. [38] | Sea cucumber (Cereus sinensis) polysaccharide | Shannon and Chao1 ↑ | PCoA/NMDS/PLS-DA: closer to NC | Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio normalized; ↑ Phasecolarctobacterium, Bifidobacterium | Acetate and total SCFA ↑; propionate and butyrate ↑ | Cecal damage reduced; structure normalized | Serum IL-2, TNF-α ↓; IL-1β ↓ (high dose) | Cecal inflammation and edema reduced. | Sea cucumber polysaccharide enhanced SCFA-producing flora, improved SCFA output, and suppressed inflammatory cytokines. |

| HNP | Chen et al. [39] | Bamboo shoot polysaccharide | Shannon and Chao1 ↑ | PCA: high-dose cluster closest to NC | F/B ratio normalized; ↑ Lactobacillus; ↓ Escherichia–Shigella | Acetate, propionate, butyrate, valerate ↑ (butyrate/valerate > inulin) | Thicker intestinal wall; reduced edema | No cytokine assay | Mucosal edema and inflammatory infiltration reversed. | Bamboo shoot polysaccharide was fermented in colon, increased SCFAs, promoted beneficial flora, and suppressed pathobionts. |

| HNP | Zeng. [40] | Blueberry leaf polyphenols | Diversity and richness restored | PCoA: clusters closer to NC | F/B ratio normalized; ↑ Muribaculum, Lactobacillus; ↓ Clostridium, Enterococcus | Acetate, propionate, butyrate, valerate, total SCFAs ↑ | Occludin, claudin-1, ZO-1 ↑ (gene/protein) | Serum IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 ↓ | Ileal necrosis and inflammatory infiltration repaired. | Blueberry leaf polyphenols repaired barrier, suppressed MAPK signaling, modulated microbiota, and promoted SCFA production. |

| HNP | Han et al. [41] | Cistanche extract/polysaccharide | Simpson and Shannon ↑ | PCoA: clusters closer to NC | ↓ Firmicutes; ↓ Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1; ↑ Blautia, Lachnospiraceae | Not measured | Not specified | Not specified | Colonic structure improved; inflammation reduced. | Cistanche effects were likely mediated by gut microbiota modulation and metabolite regulation. |

| HNP | Li et al. [42] | Antrodia polysaccharides (AEPS/AIPS) | Shannon and Simpson ↑ | PCoA/NMDS: moved away from model cluster | AEPS: ↑ Lactobacillaceae; AIPS: ↑ Staphylococcaceae/Staphylococcus | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not analyzed in detail. | Antrodia polysaccharides modulated gut microbiota; AEPS showed more favorable shift toward Lactobacillus dominance. |

| HNP | Ma et al. [43] | Fresh ginger extract | Diversity restored (after AAD-induced ↓) | PCoA/NMDS: ginger groups closer to NC | Proteobacteria ↓; Escherichia–Shigella ↓; Bacteroides ↑ | Not reported | MUC2, ZO-1 ↑; goblet cells restored | MPO expression ↓; colonic inflammation ameliorated | Epithelial shedding and disorganized crypts reversed. | Fresh ginger suppressed Escherichia–Shigella, enhanced Bacteroides, and restored barrier integrity. |

| HNP | Zhang et al. [44] | Dried ginger extract | ACE/Shannon ↓ in model; ↑ with ginger | PCoA/cluster: ginger closer to NC | ↓ Bacillus, Lachnoclostridium, E. coli–Shigella; ↑ Lactobacillus | Not measured | Not reported | Not reported | Epithelial shedding and crypt disruption improved. | Dried ginger restored diversity and beneficial Lactobacillus while reducing pathogenic E. coli–Shigella. |

| HNP | Li et al. [45] | American ginseng decoction | Richness ↔; Shannon/Simpson ↑ | PCoA/NMDS: shifted toward NC | ↓ Proteobacteria; ↑ Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes; ↓ Pseudomonas, E. coli–Shigella; ↑ Bacteroides | Not reported | Colon structure intact (H&E) | Inflammatory cell infiltration ↓ | Loose glands and epithelial shedding improved. | American ginseng decoction improved diversity and composition and restored colon structure and metabolic pathways. |

| HNP-C | Qu et al. [46] | Fermented ginseng synbiotic | Simpson, Ace, Chao, Shannon ↑ (restored) | PCA: fermented ginseng cluster closest to NC | ↑ Lactobacillus, Candidatus Stoquefichus; ↓ Bacteroides, Clostridioides | Not measured | Crypt architecture normalized; infiltration ↓ | IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α ↓; IL-10 ↑ | Colon architecture restored. | Fermentation increased β-glucosidase activity, boosted bioactive ginsenosides, normalized microbiota and cytokine balance. |

| HNP-C | Zhong et al. [47] | Astragalus polysaccharide + L. plantarum | α-diversity ↑ (combination > single > model) | PCoA: combination closest to NC | ↑ Lactobacillus, Allobaculum, Bifidobacterium; ↓ Bacteroides, Blautia | Not measured | Occludin, claudin-1, ZO-1, MUC-2 ↑; goblet cells ↑; DAO, D-LA, LPS ↓ | sIgA, IgG ↑; IL-17A, IL-4, TGF-β1 ↓ | Goblet cells and mucus area increased; edema ↓ | Astragalus synbiotic enhanced tight junctions and mucus, improved immunoglobulin profile, and promoted epithelial repair via Smad7/p-Smad3 modulation. |

| HNP-C | Tang et al. [48] | Poria polysaccharide + probiotics | Chao and Shannon ↑ (PWP > PP > WP) | PCoA/NMDS: PWP cluster closest to NC | ↑ Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes (Muribaculaceae); ↓ Proteobacteria (Sutterella) | Not measured | Mucin ↑ (histology) | IgM, IgG normalized; IgA ↑; macrophages/lymphocytes ↑ | Mucin ↑; edema ↓; improved villus morphology. | Poria-based synbiotic was associated with immune modulation and microbiota homeostasis, with more pronounced changes observed under the tested conditions. |

| HNP-C | Guo et al. [49] | B. adolescentis + β-glucan synbiotic | Shannon and Fisher ↑ (combination > single) | PCoA: combination cluster closest to NC | ↑ B. uniformis; ↓ Enterococcus, Escherichia–Shigella | Acetate, propionate, isobutyrate ↑ | Occludin, ZO-1, Mucin-2/3 ↑; D-LA, LPS ↓ | IL-6, IL-17 ↓ | Mucosal structure improved; epithelium intact. | Synbiotic increased SCFAs, repaired barrier, and modulated immunity via enrichment of B. uniformis. |

| HNP-C | Li et al. [50] | Maifan stone + L. rhamnosus GG | Not reported | Not applicable (qPCR only) | ↑ Bacteroides, Lactobacillus; ↓ Enterococcus, E. coli | Not measured | Colon epithelium arrangement restored; edema ↓ | TLR4, NF-κB ↓ in colon | Edema reduced; epithelial structure normalized. | Maifan stone carrier enhanced LGG tolerance, improved microbiota, and down-regulated TLR4/NF-κB signaling. |

| HNP-C | Shen et al. [51] | Chitosan oligosaccharide + probiotics | Shannon ↑; Chao1 trend toward recovery | PCoA: synbiotic group closer to baseline (day 0) | ↑ Firmicutes, Acidobacteriota; ↓ Desulfobacterota; shifts in Megamonas, Lachnospiraceae, Muribaculaceae | Not measured | ZO-1, occludin, claudin-1 ↑; villus height/crypt depth ↑ | TNF-α, IL-1β ↓; IgA, IgG ↑ | Edema ↓; villus height and crypt depth improved. | Chitosan oligosaccharide acted as prebiotic carrier; synbiotic restored tight junctions and reduced inflammation in a canine model. |

| Outcome | HNP Monotherapy (n = 21) | HNP-C Combination (n = 6) | Comparative Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Diversity | Reported in 20/21 studies; 1 study used DGGE only (no α-diversity indices). All studies reported ↑ Shannon/Chao1/ACE. | Reported in 5/6 studies; one study [45,50] did not assess α-diversity. All reporting studies showed increases. | Both strong; HNP-C slightly more rapid and consistent in studies with direct comparators. |

| β-Diversity | Reported in 18/21 studies (PCoA/NMDS). All 18 showed a shift toward Control; 3 did not report β-diversity. | Reported in 5/6 studies; Li et al. [45,50] used qPCR only. All reporting studies showed convergence toward NC. | HNP-C tends to show closer clustering toward the Control group in studies reporting β-diversity. |

| Key taxa shifts | Reported in 21/21 studies. Common findings: ↑ Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Muribaculaceae; ↓ Escherichia–Shigella. | Reported in 6/6 studies. Persistence of administered probiotic strains. | Similar direction overall; HNP-C yields more stable probiotic colonization. |

| SCFAs | Reported in 17/21 studies. All reported ↑ acetate/propionate/butyrate. | Quantitatively reported in 1/6 studies [49]. Other 5 did not measure SCFAs directly; some reported ↑ SCFA-producing taxa. | HNP monotherapy provides stronger direct evidence for SCFA production (17/21 studies). HNP-C efficacy is currently limited by reporting frequency (1/6 studies) but supported indirectly. |

| Barrier markers (ZO-1, Occludin, Claudin-1, MUC2, SIgA) | Reported in 16/21 studies; improved TJ proteins and mucosal integrity. | Reported in 4/6 studies; increased TJ proteins and reduced leakage markers (D-LA, LPS). | HNP-C showed improvements across multiple barrier-related markers when reported. |

| Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) | Reported in 15/21 studies; consistent decreases. | Reported in 6/6 studies; also ↓ IL-17A and ↑ IL-10. | HNP-C showed modulation across multiple cytokine markers. |

| Immune markers (IgA, IgG, IgM, FOXP3) | Reported in 11/21 studies; some ↑ IgA and ↑ FOXP3. | Reported in 5/6 studies; all showed ↑ IgA/IgG/IgM. | HNP-C showed consistent improvements in immune-related outcomes. |

| Diarrhea-related phenotypic outcomes | Reported in 18/21 studies; improved diarrhea severity and weight recovery. | Reported in 6/6 studies; all showed. phenotypic improvement | Both effective; HNP-C shows more complete and consistent reporting. |

| Histopathology | Reported in 17/21 studies; mucosal repair, ↑ goblet cells, ↓ edema. | Reported in 6/6 studies; villus height ↑, crypt integrity restored. | Comparable effects; HNP-C shows uniformly positive histology. |

| Overall consistency and strength | Mechanisms vary by herb/extract; reporting frequency variable. | Highly coherent across barrier, immunity, taxa, and histology. | HNP-C consistently showed recovery across multiple domains. The two direct comparator studies suggest potentially additive benefits across microbial, barrier, and immune endpoints. |

3.4. Functional Recovery: SCFA Metabolism and Barrier Integrity

3.5. Immune and Inflammatory Responses

3.6. Histopathological Recovery

3.7. Diarrhea-Related Phenotypic Outcomes

3.8. Comparative Effects Between HNP and HNP-C Using Overlapping Herbal Sources

3.8.1. Poria (Wolfiporia cocos) Group (Table 4)

| Item | HNP (PCP, PCY) | HNP-C (WP + Probiotics) |

|---|---|---|

| Barrier | ↑ ZO-1, Occludin; epithelial repair | ↑ mucin, ↑ goblet cells; ↓ leakage markers |

| Immune | ↓ NF-κB; GPR41/43 ↑ | ↑ IgA/IgG/IgM; ↑ macrophage/lymphocyte activity |

| Microbiota | Restored Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes; ↓ pathogens | Relatively stable community structure; sustained shifts |

| Histology | Edema ↓; villus repair | More pronounced epithelial regeneration |

| Mechanism | SCFA receptor (GPR41/43) activation | Combined barrier and immune modulation |

3.8.2. Astragalus (Astragalus spp.) Group (Table 5)

| Item | HNP (WAP) | HNP-C (APS + L. plantarum) |

|---|---|---|

| SCFAs | ↑ propionate, ↑ butyrate | Not directly measured |

| Barrier | Villus restoration | ↑ Occludin/Claudin-1/ZO-1/MUC-2; ↓ DAO/D-LA/LPS |

| Immune | ↓ inflammation | ↑ IgA/IgM/IgG |

| Mechanism | Microbiota + SCFA effects | ↑ Smad7; ↓ p-Smad3; pathway-level modulation |

3.8.3. Integrated Summary

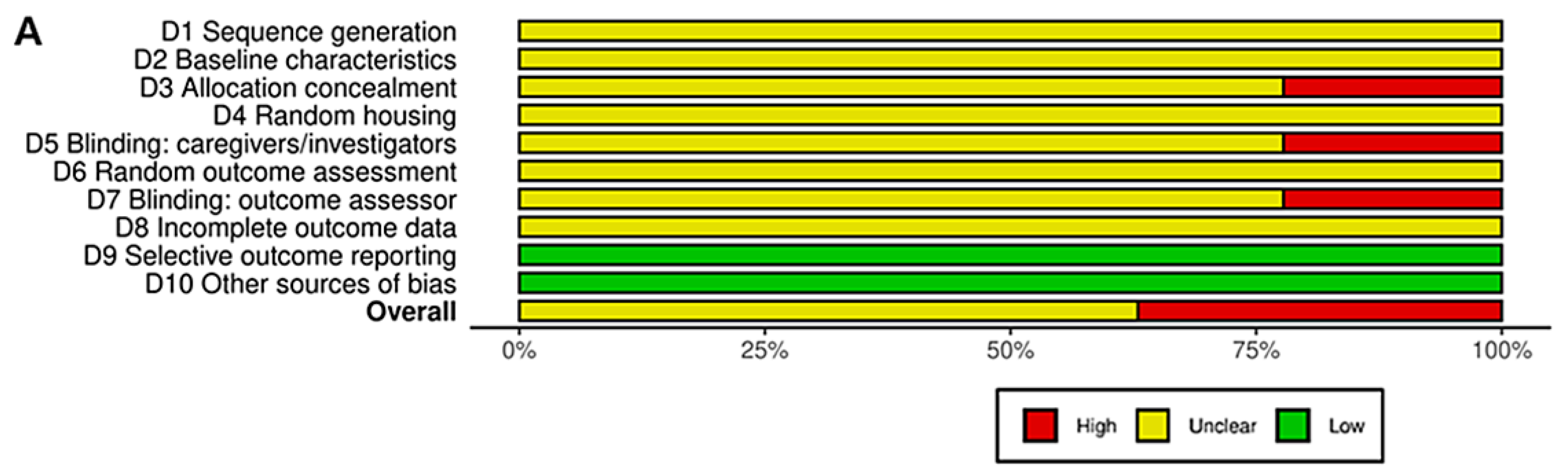

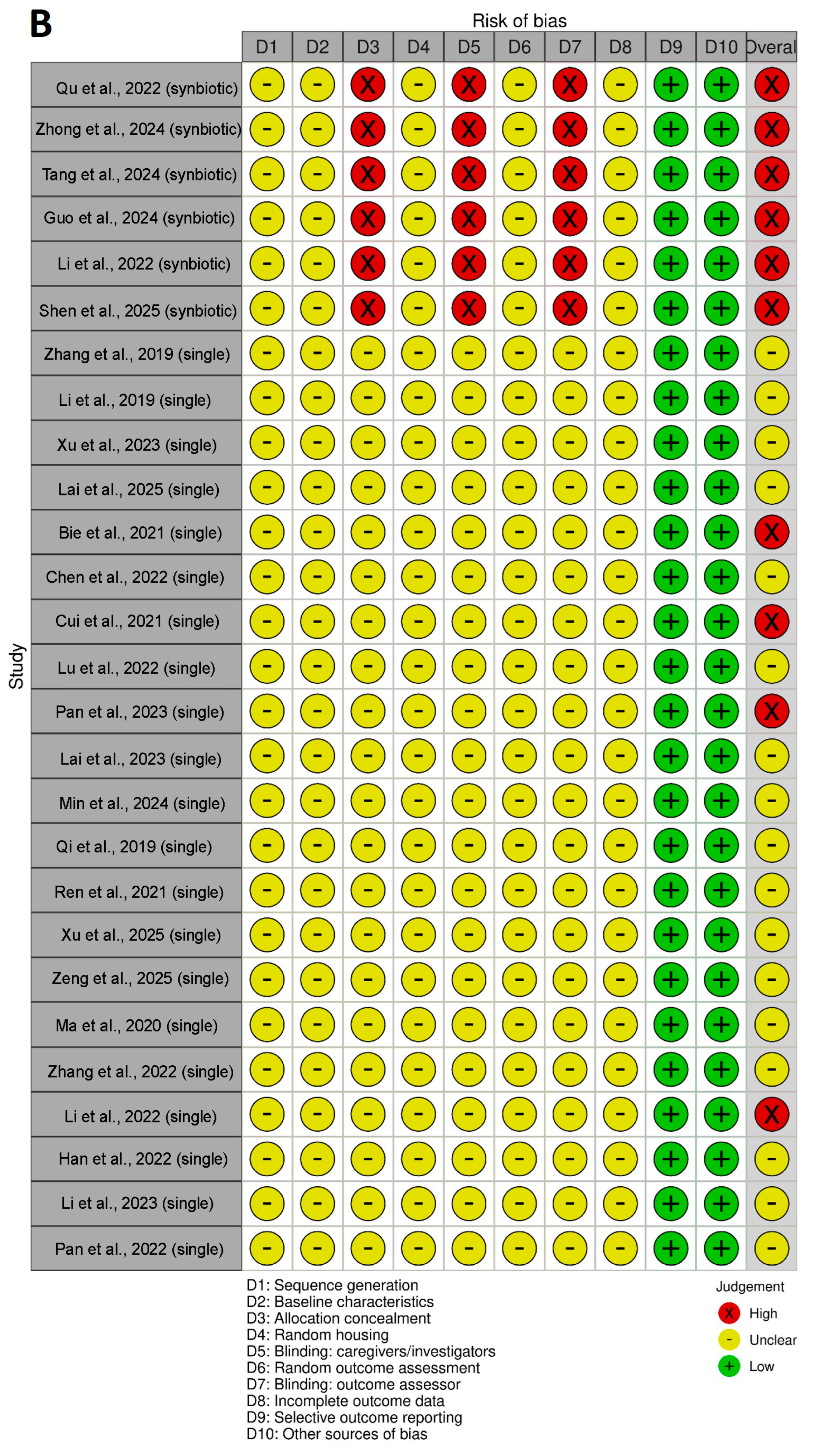

3.9. Risk of Bias and Quality of Reporting

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of HNP Monotherapy

4.2. Effects of HNP–Probiotic Combinations (HNP-C)

4.3. Probiotics vs. HNP vs. HNP–C: Comparative Mechanistic Insights

4.4. Comparative Insights from Overlapping Herbal Sources

4.5. Future Directions

4.6. Overall Synthesis and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAD | Antibiotic-associated diarrhea |

| SCFA/SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acid/short-chain fatty acids |

| HNP | Herbal/Natural Product |

| HNP-C | Herbal/Natural Product Combination |

| DGGE | Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| NMDS | Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| GC–MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| MUC2 | Mucin 2 |

| ZO-1 | Zonula Occludens-1 |

| OC-1/Occludin | Occludin (tight-junction protein) |

| TJ | Tight Junction |

| IgA/IgG/IgM | Immunoglobulin A/G/M |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| DAO | Diamine Oxidase |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead Box P3 |

| IL-1β/IL-6/IL-10/IL-17A | Interleukin-1β/Interleukin-6/Interleukin-10/Interleukin-17A |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-B |

| F/B ratio | Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes Ratio |

| PC | Positive Control |

| NC | Normal Control |

| L/M/H | Low/Medium/High dose |

| SIgA | Secretory Immunoglobulin A |

| Smad7/p-Smad3 | Smad7/phosphorylated Smad3 |

| CFU | Colony Forming Unit |

References

- McFarland, L.V. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea: Epidemiology, trends and treatment. Future Microbiol. 2008, 3, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.L.; Sidhick, S.T.; Maharajan, M.K.; Shanmugham, S.; Ingle, P.V.; Kumar, S.; Ching, S.M.; Lee, Y.Y.; Veettil, S.K. Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea—An umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 23, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patangia, D.V.; Anthony Ryan, C.; Dempsey, E.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. MicrobiologyOpen 2022, 11, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, S.A.; Nzakizwanayo, J.; Rodgers, A.M.; Zhao, L.; Weiser, R.; Tekko, I.A.; McCarthy, H.O.; Ingram, R.J.; Jones, B.V.; Donnelly, R.F.; et al. Antibiotic therapy and the gut microbiome: Investigating the effect of delivery route on gut pathogens. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, A.M.; Sinani, H.; Schloss, P.D. Antibiotic-induced alterations of the murine gut microbiota and subsequent effects on colonization resistance against Clostridium difficile. mBio 2015, 6, e00974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.; Baloch, Z.; Shah, Z.; Cui, X.; Xia, X. The intestinal microbiota: Impacts of antibiotics therapy, colonization resistance, and diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Zeng, Z.L.; Zhao, Z.B.; Yan, X.L.; Zheng, J.; Chen, W.H.; Wang, Z.X.; Xie, H.; Liu, J.H. Antibiotic-induced gut microbiota disruption promotes vascular calcification by reducing short-chain fatty acid acetate. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekirov, I.; Tam, N.M.; Jogova, M.; Robertson, M.L.; Li, Y.; Lupp, C.; Finlay, B.B. Antibiotic-induced perturbations of the intestinal microbiota alter host susceptibility to enteric infection. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 4726–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.R.; Collins, J.J.; Relman, D.A. Antibiotics and the gut microbiota. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 4212–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya, A.; Ferrer, M. Functional redundancy-induced stability of gut microbiota subjected to disturbance. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, M.A.K.; Sarker, M.; Li, T.; Yin, J. Probiotic species in the modulation of gut microbiota: An overview. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9478630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and Synbiotics on human health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Luo, S. Plant polysaccharides modulate immune function via the gut microbiome and may have potential in COVID-19 therapy. Molecules 2022, 27, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Che, Q.; Guo, Z.; Song, T.; Zhao, J.; Xu, D. Modulatory effects of traditional Chinese medicines on gut microbiota and the microbiota-gut-x axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1442854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrosa, L.F.; Fabi, J.P. Polysaccharides from medicinal plants: Bridging ancestral knowledge with contemporary science. Plants 2024, 13, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, H.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Feng, W.; Peng, C. Repairing gut barrier by traditional Chinese medicine: Roles of gut microbiota. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1389925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Shin, M.S.; Choi, Y.K. Ameliorative effects of Zingiber officinale Rosc on antibiotic-associated diarrhea and improvement in intestinal function. Molecules 2024, 29, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Bajinka, O.; Jarju, P.O.; Tan, Y.; Taal, A.M.; Ozdemir, G. The varying effects of antibiotics on gut microbiota. AMB Express 2021, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Meng, X.; Zheng, H.; Gu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wang, S.; Lin, J.; Li, T.; Liao, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Deciphering the pharmacological mechanisms of Shenlingbaizhu formula in antibiotic-associated diarrhea treatment: Network pharmacological analysis and experimental validation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 329, 118129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Sun, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Yuan, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, Q. Effect of traditional Chinese medicine on treating antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2022, 2022, 6108772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Mei, C.F.; Wang, F.Y.; Tang, X.D. Relationship among Chinese herb polysaccharide (CHP), gut microbiota, and chronic diarrhea and impact of CHP on chronic diarrhea. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5837–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.-D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, W.-L.; Jin, X.-Y.; Fan, Y.-H.; Wang, B. Efficacy of Shenlingbaizhusan for antibiotic-associated diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Herb. Med. 2023, 40, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhan, M.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Song, M. Investigating the interaction between tangeretin metabolism and amelioration of gut microbiota disorders using dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis and antibiotic-associated diarrhea models. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 10, 101049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.D.; Shao, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.J.; Xia, Y.S.; Li, S.; Sun, Y. Ameliorative Effect of panax quinquefolius polysaccharides on Antibiotic-associated diarrhea Induced by clindamycin phosphate. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2021, 42, 354–361. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.J.; Kim, H.; Yambe, N.; Shin, M.S. Ameliorative effects of Korean-red-ginseng-derived polysaccharide on antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Polymers 2024, 16, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.L.; Li, S.S.; Qu, D.; Chen, L.X.; Gong, R.Z.; Gao, R.Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.X. Effects of ginseng neutral polysaccharide on gut microbiota in antibiotic-associated diarrhea mice. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2019, 44, 811–818. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.Y.; Zhang, C.Q.; Zhang, X.Q.; Zeng, H.; Dong, C.H.; Chen, X.; Ding, K. A galacturonan from Dioscorea opposita Thunb. regulates fecal and impairs IL-1 and IL-6 expression in diarrhea mice. Glycoconj. J. 2022, 39, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qi, Y.; Ren, D.; Qu, D.; Sun, Y. The structure features and improving effects of polysaccharide from Astragalus membranaceus on antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Antibiotics 2019, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, L.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, L.; Chen, X. Poria cocos polysaccharide ameliorated antibiotic-associated diarrhea in mice via regulating the homeostasis of the gut microbiota and intestinal mucosal barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, M.; Guo, X.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, Q.; Deng, H.; Song, C. Restoration of antibiotic associated diarrhea induced gut microbiota disorder by using Dictyophora indusiata water-insoluble polysaccharides in C57BL/6J mice. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1607365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bie, N.; Duan, S.; Meng, M.; Guo, M.; Wang, C. Regulatory effect of non-starch polysaccharides from purple sweet potato on intestinal microbiota of mice with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 5563–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liang, T.S.; Jin, Q.; Shen, C.; Zhang, Y.F.; Jing, P. Chinese yam (Dioscorea opposita Thunb.) alleviates antibiotic-associated diarrhea, modifies intestinal microbiota, and increases the level of short-chain fatty acids in mice. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, P.P.; Peng, J.F.; Li, J.D.; Ding, K. Effects of Nemacystus decipiens polysaccharide on mice with antibiotic associated diarrhea and colon inflammation. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Deng, H.; Fang, Q.; Ma, L.; Lei, H.; Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Song, C. Water-insoluble polysaccharide extracted from Poria cocos alleviates antibiotic-associated diarrhea based on regulating the gut microbiota in mice. Foods 2023, 12, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.L.; Li, H.X.; Zhu, X.Y.; Luo, Z.S.; Rao, S.Q.; Yang, Z.Q. Regulatory effect of intracellular polysaccharides from Antrodia cinnamomea on the intestinal microbiota of mice with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2022, 14, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Wang, Y.; Elango, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, K.; Jin, Y. Cereus sinensis polysaccharide alleviates antibiotic-associated diarrhea based on modulating the gut microbiota in C57BL/6 mice. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 751992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Guan, X.F.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhuang, W.J.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Zheng, Y.F.; Wang, Q. Polysaccharides from Bamboo Shoot (Leleba oldhami Nakal) Byproducts Alleviate Antibiotic-Associated diarrhea in Mice through Their Interactions with Gut microbiota. Foods 2022, 11, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y. Modulatory Effects of Blueberry Leaf Polyphenols on Antibiotic-Induced Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis. Master’s thesis, Chengdu University, Chengdu, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.Y.; Yang, D.; Zhou, S.Q.; Qiao, Y.M.; Yin, J.; Jin, M.; Li, J.W. Regulative effect of active components of Cistanche deserticola on intestinal dysbacteriosis induced by antibiotics in mice. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za Zhi 2022, 38, 766–770. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.X.; Ji, D.; Lu, C.L.; Ye, Q.Y.; Zhao, L.H.; Gao, Y.J.; Gao, L.; Yang, Z.Q. Regulatory effect of polysaccharides from Antrodia cinnamomea in submerged fermentation on gut microbiota in mice with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Food Sci. 2023, 44, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.J.; Wang, H.J.; Ma, X.J.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.J.; Li, H.; Su, J.R.; Zhang, C.E.; Huang, L.Q. Modulation of gut microbiota and intestinal barrier function during alleviation of antibiotic-associated diarrhea with rhizoma Zingiber officinale (Ginger) extract. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10839–10851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Zhang, C.E.; Yu, X.H.; Ma, Y.Q.; Li, M.; Duan, X.Y.; Ma, Z.J. Modulation of gut microbiota during alleviation of antibiotic-associated diarrhea with Zingiberis rhizoma. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2022, 47, 1316–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.J.; Zhang, C.E.; Ma, Z.J.; Duan, X.Y. Effects of Xiyangshen (Panacis Quinquefolii Radix) on intestinal flora in rats with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Chin. Arch. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2022, 40, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Yang, F.; Shi, X. Limosilactobacillus fermentum-fermented ginseng improved antibiotic-induced diarrhoea and the gut microbiota profiles of rats. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 3476–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, B.; Liang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, S. Combination of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ELF051 and astragalus polysaccharides improves intestinal barrier function and gut microbiota profiles in mice with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 17, 4267–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Ma, X.; Song, X.; Chen, W. Probiotic powder with polysaccharides from Wolfiporia cocos alleviates antibiotic-associated diarrhea by modulating immune activities and gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; He, X.; Yu, L.; Tian, F.; Chen, W.; Zhai, Q. Bifidobacterium adolescentis CCFM1285 combined with yeast β-glucan alleviates the gut microbiota and metabolic disturbances in mice with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 3709–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Qu, Q.; Liao, Y.; Yang, F.; Sheng, M.; Feng, L.; Shi, X. Effect of maifan stone on the growth of probiotics and regulation of gut microbiota. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 75, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, J.; Tong, J.; Yao, H.; Zhang, H. Synbiotic supplementation mitigates antibiotic-associated diarrhea by enhancing gut microbiota composition and intestinal barrier function in a canine model. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 2586–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Quintero, D.F.; Kok, C.R.; Hutkins, R. The future of Synbiotics: Rational formulation and design. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 919725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.S.; Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Reimer, R.A.; Reid, G.; Verbeke, K.; Scott, K.P.; Holscher, H.D.; Azad, M.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of Synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.T.; Lee, K.G.; Lee, A.P.; Teo, J.K.H.; Lim, H.L.; Kim, S.S.Y.; Tan, A.H.M.; Lam, K.P. DOK3 maintains intestinal homeostasis by suppressing JAK2/STAT3 signaling and S100a8/9 production in neutrophils. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.H.; Che, X.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.H.; Ma, H.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, T.I.; Kim, W.H.; Kim, S.W.; Cheon, J.H. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid Cells-1 agonist regulates intestinal inflammation via CD177+ neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 650864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.T.; Cresci, G.A.M. The immunomodulatory functions of butyrate. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 6025–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De la Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, K. The effect of probiotics on the production of short-chain fatty acids by human intestinal microbiome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadlec, R.; Jakubec, M. The effect of prebiotics on adherence of probiotics. J. Dairy. Sci. 2014, 97, 1983–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, K.R.; Naik, S.R.; Vakil, B.V. Probiotics, prebiotics and Synbiotics—A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 7577–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study ID | Intervention Type | Intervention (Source Herb—Fraction/Extract + Dose/Duration) | Animal Model | AAD Induction (Agent, Duration) | Groups (n) | Comparator Arms | Treatment Duration | Total Period | Microbiome Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xu et al. [25] | HNP | Citrus reticulata—Tangeretin flavonoid (250 ppm, 10 days; co-administered with antibiotics) | C57BL/6 J mice | Ampicillin + Neomycin, 10 days | n = 8 × 2 | AB-only vs. HNP-only | 10 days | 10 days | 16S rRNA (V3–V4), in vitro fermentation |

| Ren et al. [26] | HNP | Panax quinquefolius—Water-soluble polysaccharide (100 mg/kg, 7 days) | Wistar rats | Clindamycin phosphate, 5 days | n = 6 × 4 | NC/Model/NR/HNP-only | 7 days | 12 days | 16S rRNA sequencing |

| Min, et al. [27] | HNP | Panax ginseng—Polysaccharide fraction (100/300 mg/kg, 12 days) | BALB/c mice | Lincomycin, 9 days | n = 7 × 4 | NC/Model/HNP-low/high | 12 days | 21 days | 16S rRNA |

| Qi et al. [28] | HNP | Panax ginseng—Neutral polysaccharide (dose NR, 7 days) | BALB/c mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 10 × 4 | NC/Model/NR/HNP-only | 7 days | 10 days | 16S rRNA (V3–V4) |

| Pan et al. [29] | HNP | Dioscorea opposita—Sulfated polysaccharide (30 mg/kg, 14 days; antibiotics days 1–7) | Mice | Mixed antibiotics, 7 days | n = 8 × 3 | NC/Model/HNP-only | 14 days | 14 days | 16S rRNA DGGE |

| Li S, et al. [30] | HNP | Astragalus membranaceus—Water-soluble polysaccharide (100 mg/kg, 7 days) | Wistar rats | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 4 days | n = 6 × 4 | NC/Model/NR/HNP-only | 7 days | 11 days | 16S rRNA (V3–V4) |

| Xu et al. [31] | HNP | Poria cocos—Water-soluble polysaccharide (250 mg/kg/day, 7 days) | Mice | Broad-spectrum antibiotics, 7 days | n = 6 × 4 | NC/AB-only/HNP-only/Positive Control | 7 days | 14 days | 16S rDNA |

| Lai et al. [32] | HNP | Dictyophora indusiata—Water-insoluble polysaccharide (300 mg/kg, 7 days) | C57BL/6 J mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 7 × 3 | NC/Model (NR-like)/HNP-only | 7 days | 10 days | 16S rRNA + GC–MS |

| Bie et al. [33] | HNP | Ipomoea batatas—Polysaccharide fraction (0.1–0.4 g/kg, 14 days) | BALB/c mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 10 × 5 | NC/Model/HNP (Low/Mid/High) | 14 days | 17 days | 16S rRNA |

| Zhang et al. [34] | HNP | Dioscorea opposita—Water extract (dose NR, 10 days) | BALB/c mice | Ampicillin, 5 days | n = 10 × 5 | NC/Model/HNP (Low/Mid/High) | 10 days | 15 days | PCR-DGGE |

| Pan et al. [35] | HNP | Nemacystus decipiens—Polysaccharide fraction (30 mg/kg/day, 14 days) | C57BL/6 mice | Four-antibiotic mix, 7 days | n = 8 × 3 | NC/Model/HNP-only | 14 days | 21 days | 16S rRNA |

| Lai et al. [36] | HNP | Poria cocos—Water-insoluble polysaccharide (300 mg/kg/day, 7 days) | C57BL/6 mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 7 × 4 | NC/Model/HNP-only/NR | 7 days | 10 days | 16S rRNA |

| Lu et al. [37] | HNP | Antrodia cinnamomea—Intracellular polysaccharide (8 days) | ICR mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 7 × 6 | NC/Model/HNP (L/M/H)/FOS (PC) | 8 days | 11 days | 16S rRNA |

| Cui et al. [38] | HNP | Cereus sinensis—Polysaccharide (75–300 mg/kg, 9 days) | C57BL/6 mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 3 × 6 | NC/Model/NR/HNP (L/M/H) | 9 days | 12 days | 16S rRNA + GC–MS |

| Chen et al. [39] | HNP | Leleba oldhami—Bamboo-shoot polysaccharide (100–400 mg/kg, 15 days) | Kunming mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 6 × 6 | NC/Model/Inulin (PC)/HNP (L/M/H) | 15 days | 18 days | 16S rRNA + SCFA detection |

| Zeng. [40] | HNP | Vaccinium corymbosum—Leaf polyphenol extract (100–300 mg/kg, 14 days) | BALB/c mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 10 × 6 | NC/Model/HNP (L/M/H)/GOS (PC) | 14 days | 17 days | 16S rRNA + GC–MS |

| Han et al. [41] | HNP | Cistanche deserticola—Extract/polysaccharide/echinacoside (7 days) | BALB/c mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 7 days | n = 8 × 6 | NC/Model/Inulin (PC)/HNP fractions | 7 days | 14 days | 16S rDNA |

| Li et al. [42] | HNP | Antrodia cinnamomea—Polysaccharide fractions (0.03 g/kg, 3 days) | ICR mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 6 × 5 | NC/Model/HNP fractions/FOS (PC) | 3 days | 6 days | 16S rDNA |

| Ma et al. [43] | HNP | Zingiber officinale—Fresh ginger extract (1.2 or 4.8 g/kg/day, 7 days) | SD rats | Clindamycin + Ampicillin + Streptomycin, 7 days | n = 10 × 4 | NC/Model/HNP-low/high | 7 days | 21 days | 16S rRNA |

| Zhang et al. [44] | HNP | Zingiberis rhizoma—Dried ginger extract (200–400 mg/kg/day, 14 days) | SD rats | Same three-antibiotic mix, 7 days | n = 10 × 5 | NC/Model/HNP-low/high/PC | 14 days | 21 days | 16S rRNA |

| Li et al. [45] | HNP | Panax quinquefolium—Decoction extract (1–2 g/kg/day, 7 days) | SD rats | Three-antibiotic mix, 7 days | n = 10 × 4 | NC/Model/HNP-low/high | 7 days | 21 days | 16S rRNA |

| Qu et al. [46] | HNP-C | Panax ginseng (fermented with Limosilactobacillus fermentum)—Fermented ginseng mixture | SD rats | Cephalexin + Clindamycin + Streptomycin, 7 days | n = 8 × 5 | NC/Model/HNP-C/Probiotic-only/Mixed Combo | 5 days | 12 days | 16S rRNA |

| Zhong et al. [47] | HNP-C | Astragalus membranaceus polysaccharide + Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ELF051 | C57BL/6 mice | Amoxicillin + Clindamycin + Streptomycin, 14 days | n = 10 × 5 | NC/Model/HNP-only/PRO-only/HNP-C | 14 days | 28 days | 16S rRNA |

| Tang et al. [48] | HNP-C | Wolfiporia cocos polysaccharide + probiotic mixture (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus) | Kunming mice | Ampicillin sodium, 5 days | n = 10 × 5 | NC/Model/HNP-only/PRO-only/HNP-C | 14 days | 19 days | 16S rRNA + CFU |

| Guo et al. [49] | HNP-C | Bifidobacterium adolescentis + yeast β-glucan | BALB/c mice | Lincomycin hydrochloride, 3 days | n = 10 × 6 | NC/Model/HNP-only/PRO-only/HNP-C/NR | 7 days | 10 days | 16S rRNA + metabolomics |

| Li et al. [50] | HNP-C | Maifan stone + Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | SD rats | Clindamycin + Cephalexin + Streptomycin, 5 days | n = 10 × 6 | NC/Model/NR/PRO-only/HNP-only/HNP-C | 5 days | 10 days | qPCR (no 16S) |

| Shen et al. [51] | HNP-C | Chitosan oligosaccharides + multi-strain probiotic mixture | Beagle dogs | Enrofloxacin + Metronidazole, 7 days | n = 8 × 2 | Model vs. HNP-C | 28 days | 35 days | 16S rRNA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hwang, J.H.; Choi, Y.-K. Herbal and Natural Products for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies Focusing on Molecular Microbiome and Barrier Outcomes. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010064

Hwang JH, Choi Y-K. Herbal and Natural Products for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies Focusing on Molecular Microbiome and Barrier Outcomes. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Ji Hye, and You-Kyoung Choi. 2026. "Herbal and Natural Products for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies Focusing on Molecular Microbiome and Barrier Outcomes" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010064

APA StyleHwang, J. H., & Choi, Y.-K. (2026). Herbal and Natural Products for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies Focusing on Molecular Microbiome and Barrier Outcomes. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010064