Biomolecule–Photosensitizer Conjugates: A Strategy to Enhance Selectivity and Therapeutic Efficacy in Photodynamic Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

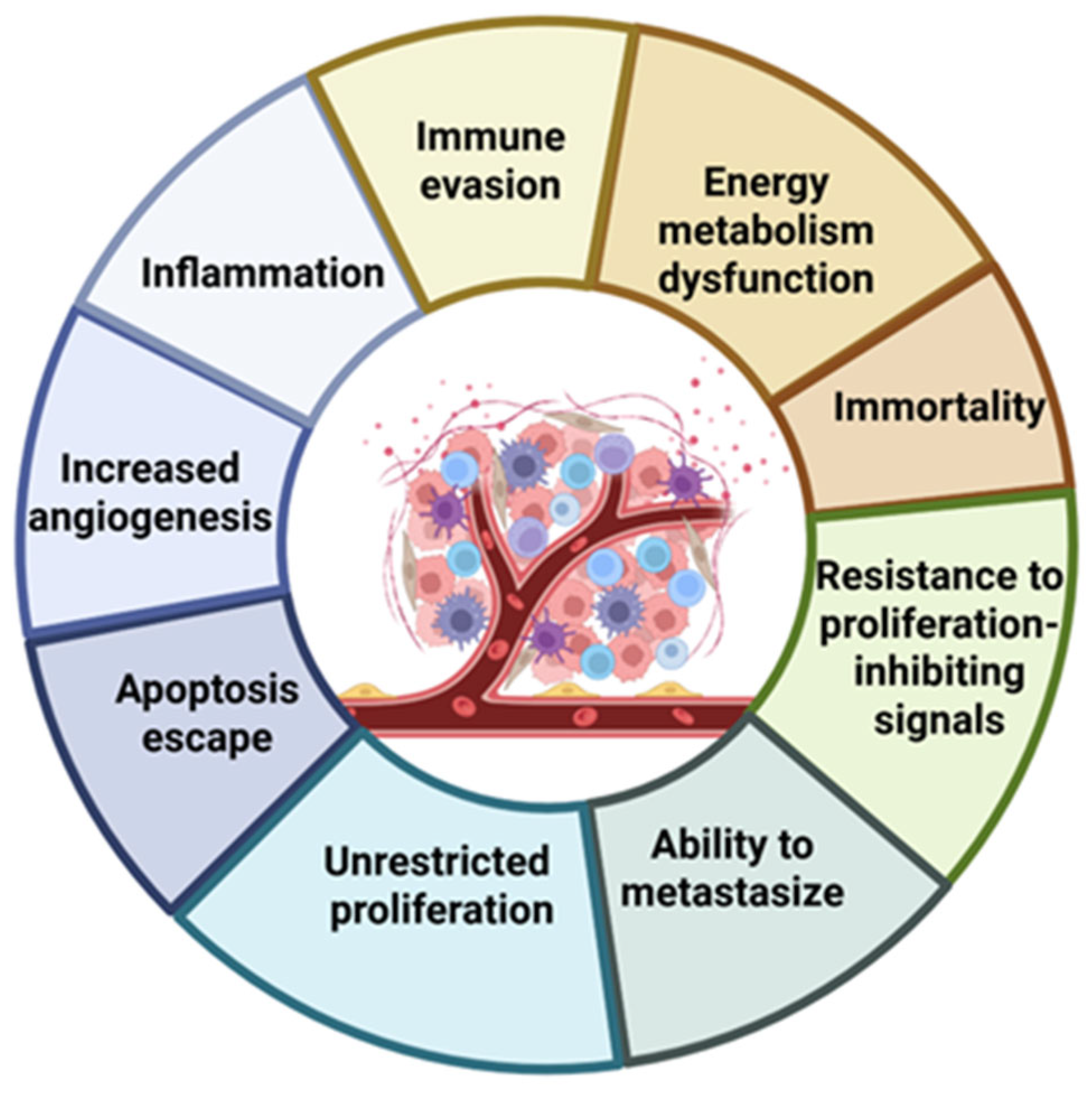

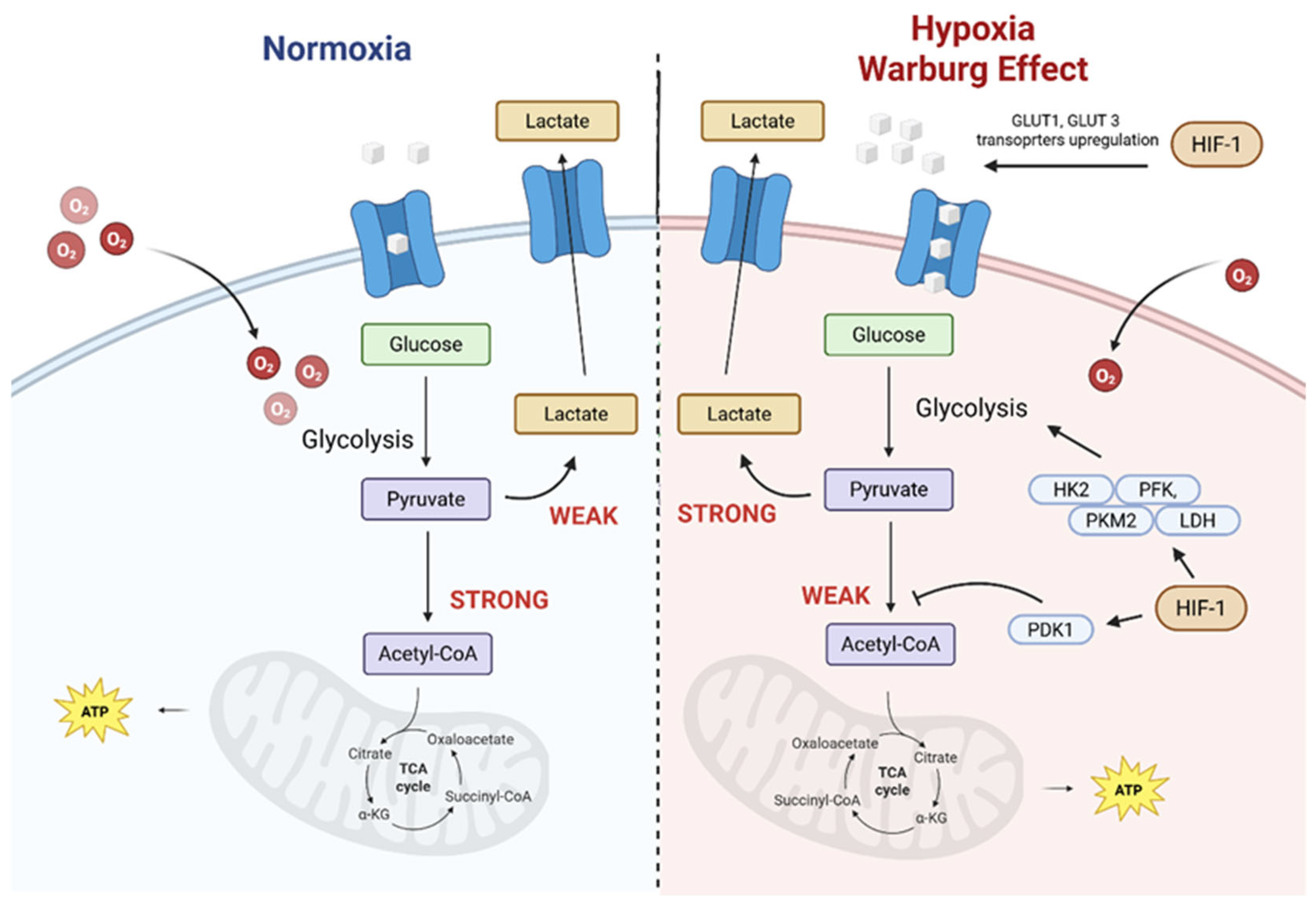

2. The Tumour Microenvironment as a Target for Photosensitizer Delivery

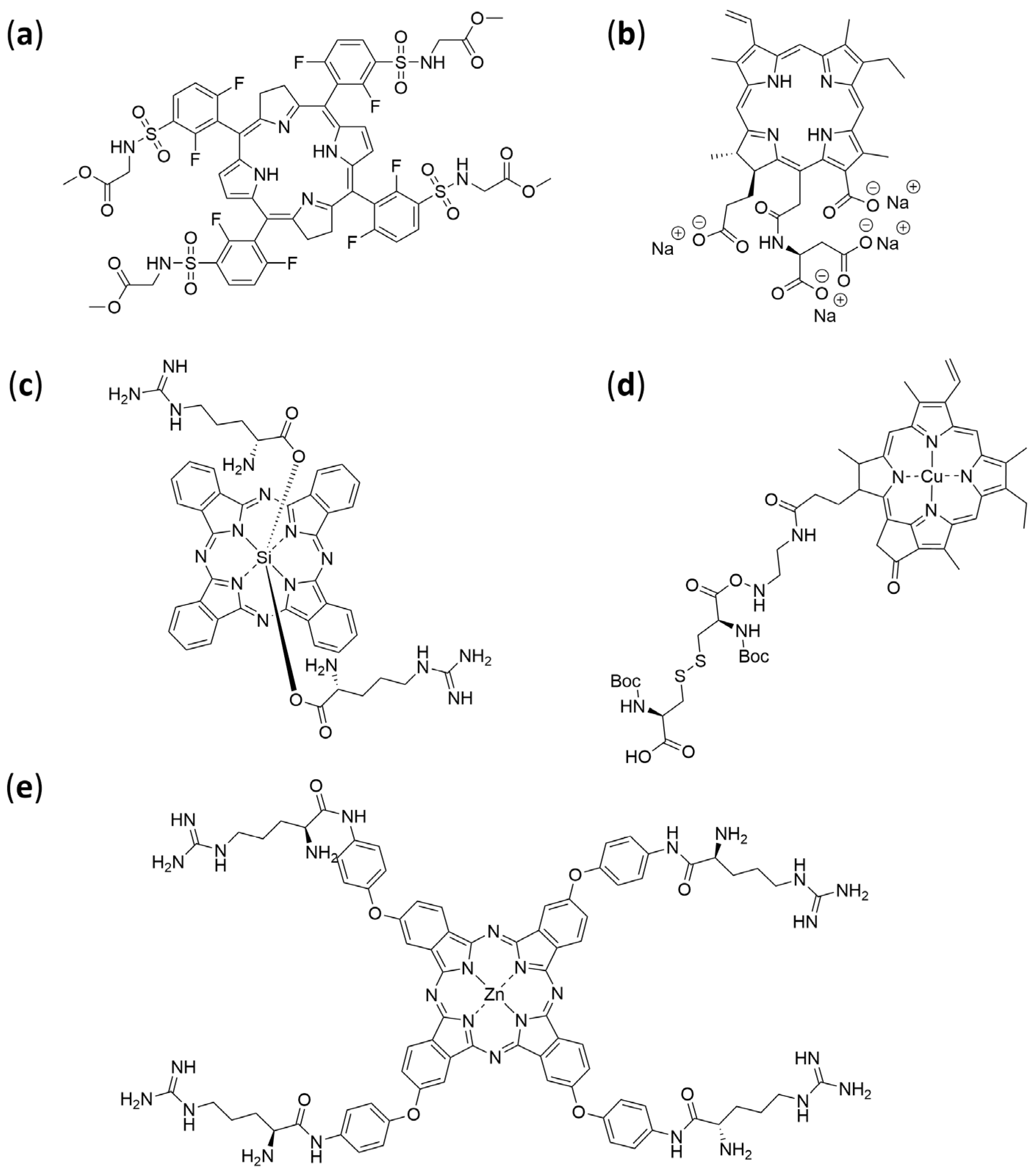

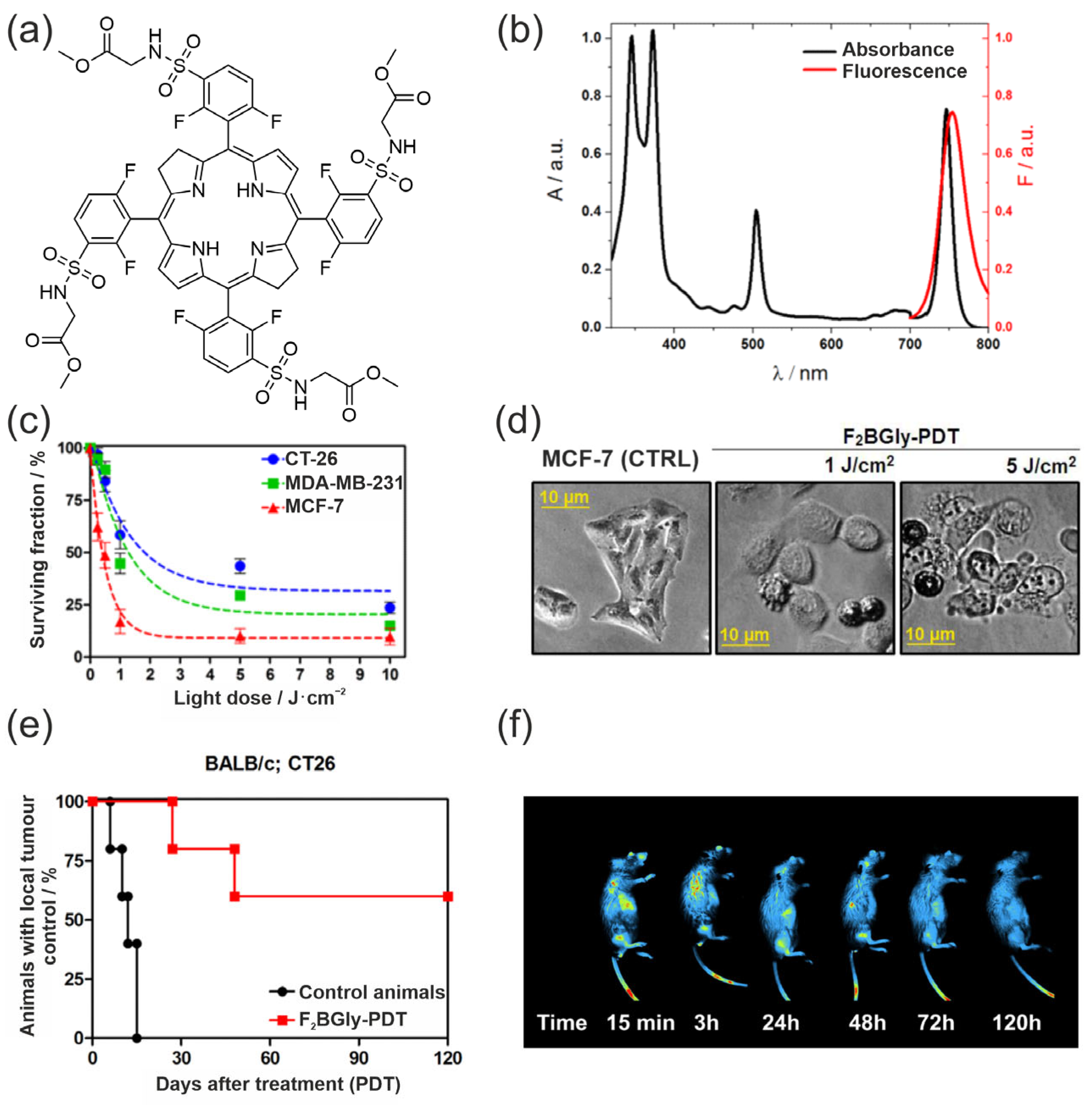

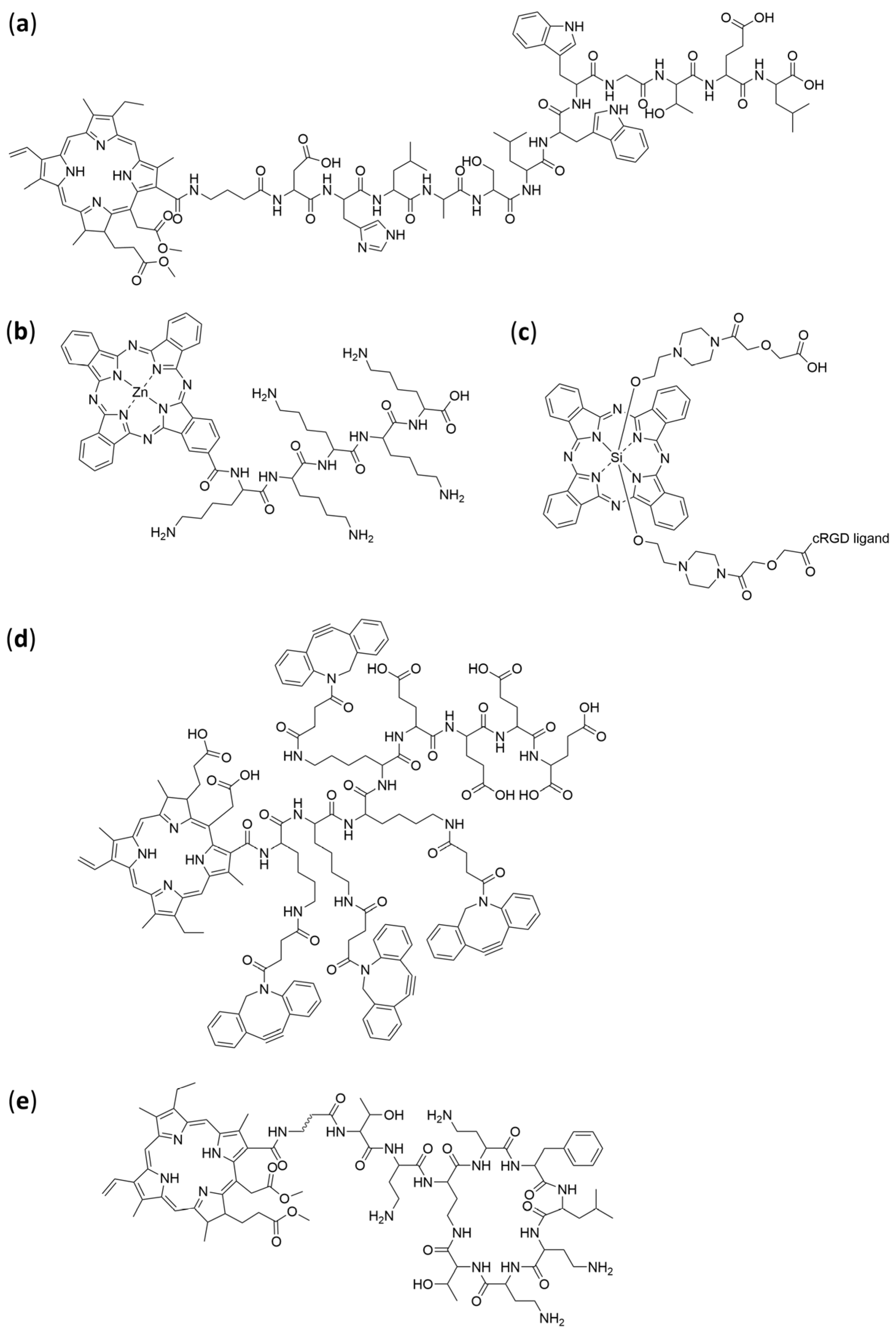

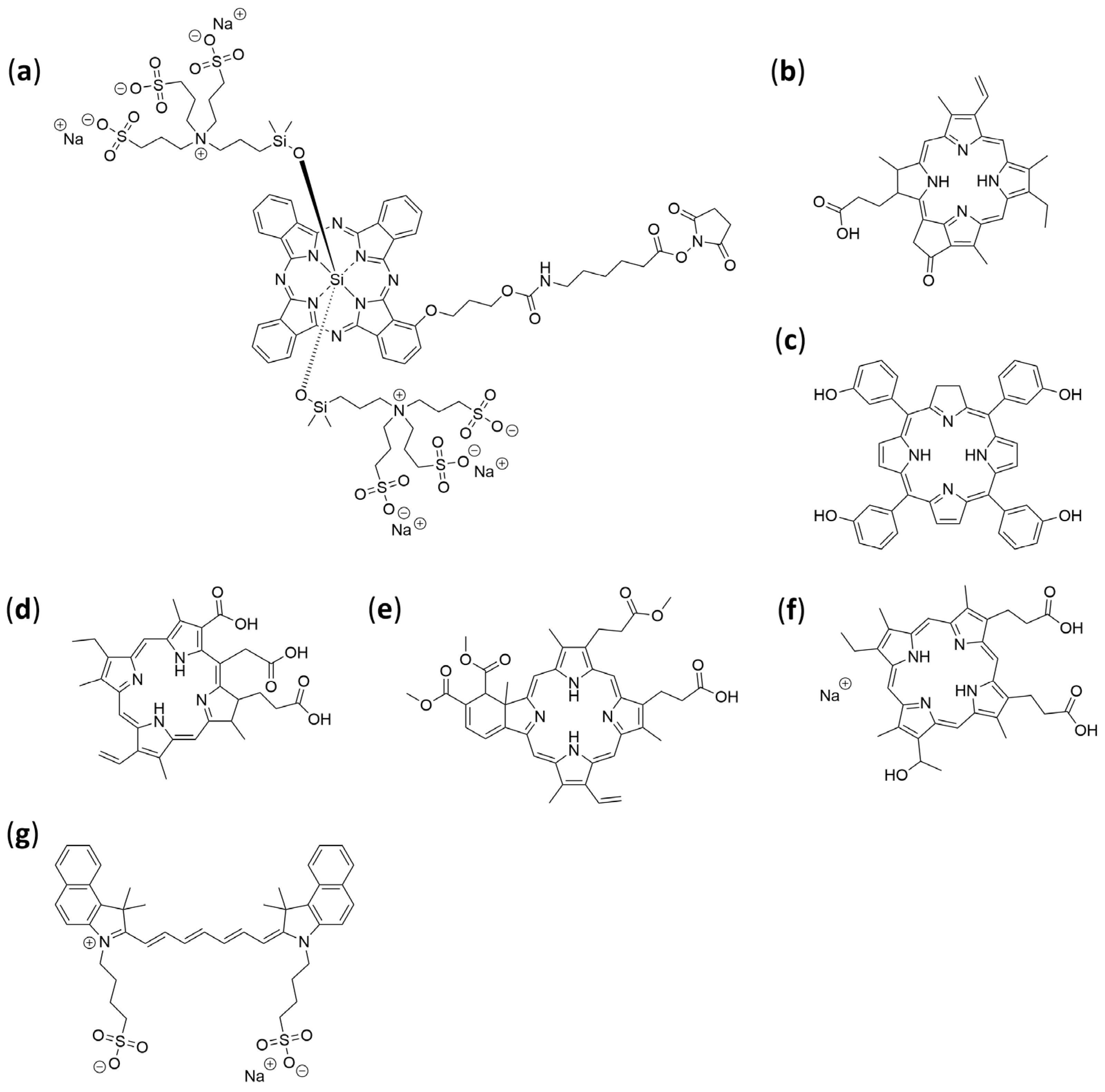

3. Development of Biomolecule–PS Conjugates

4. Types of Biomolecules Used for Photosensitizer Modification

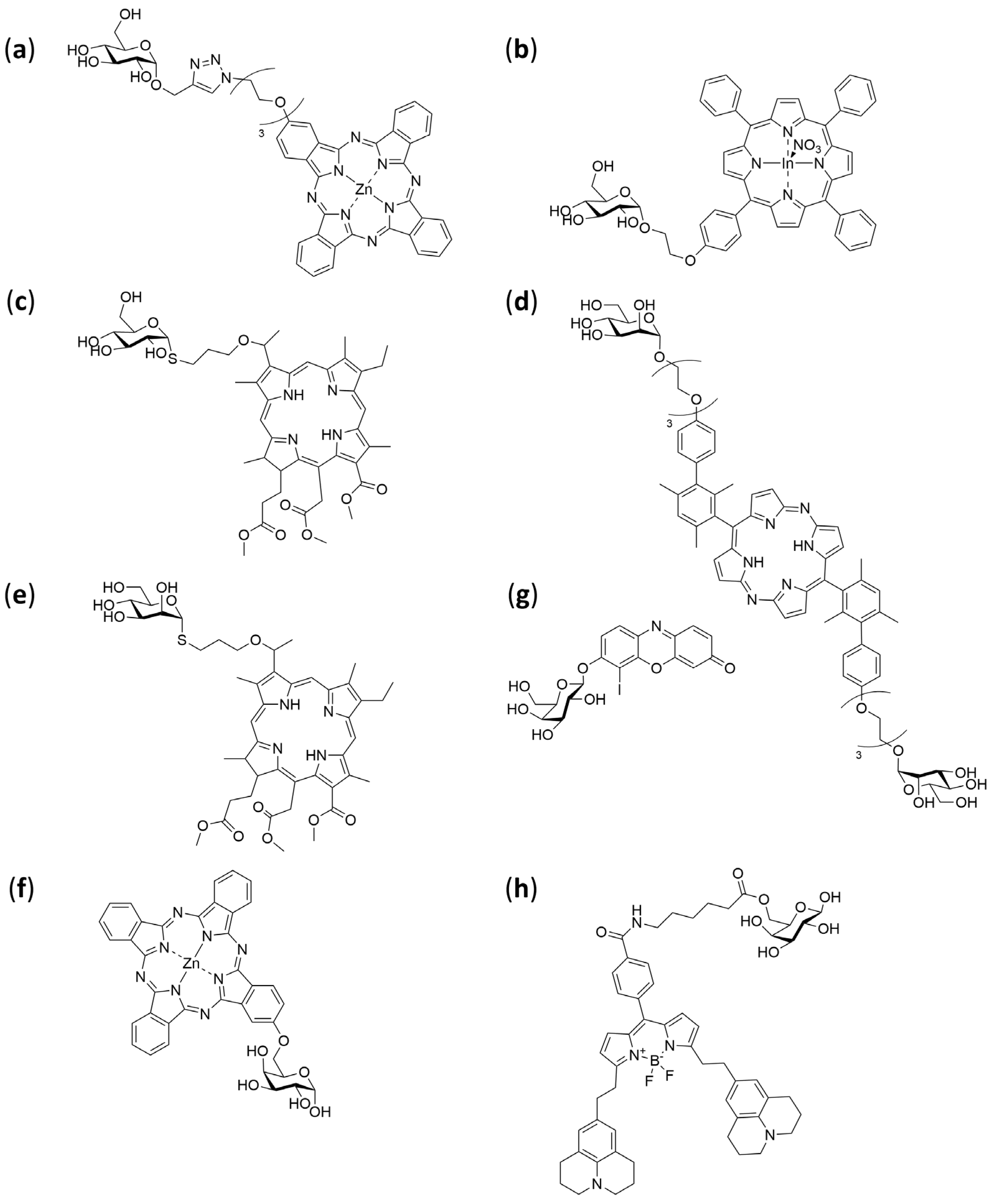

4.1. Carbohydrates

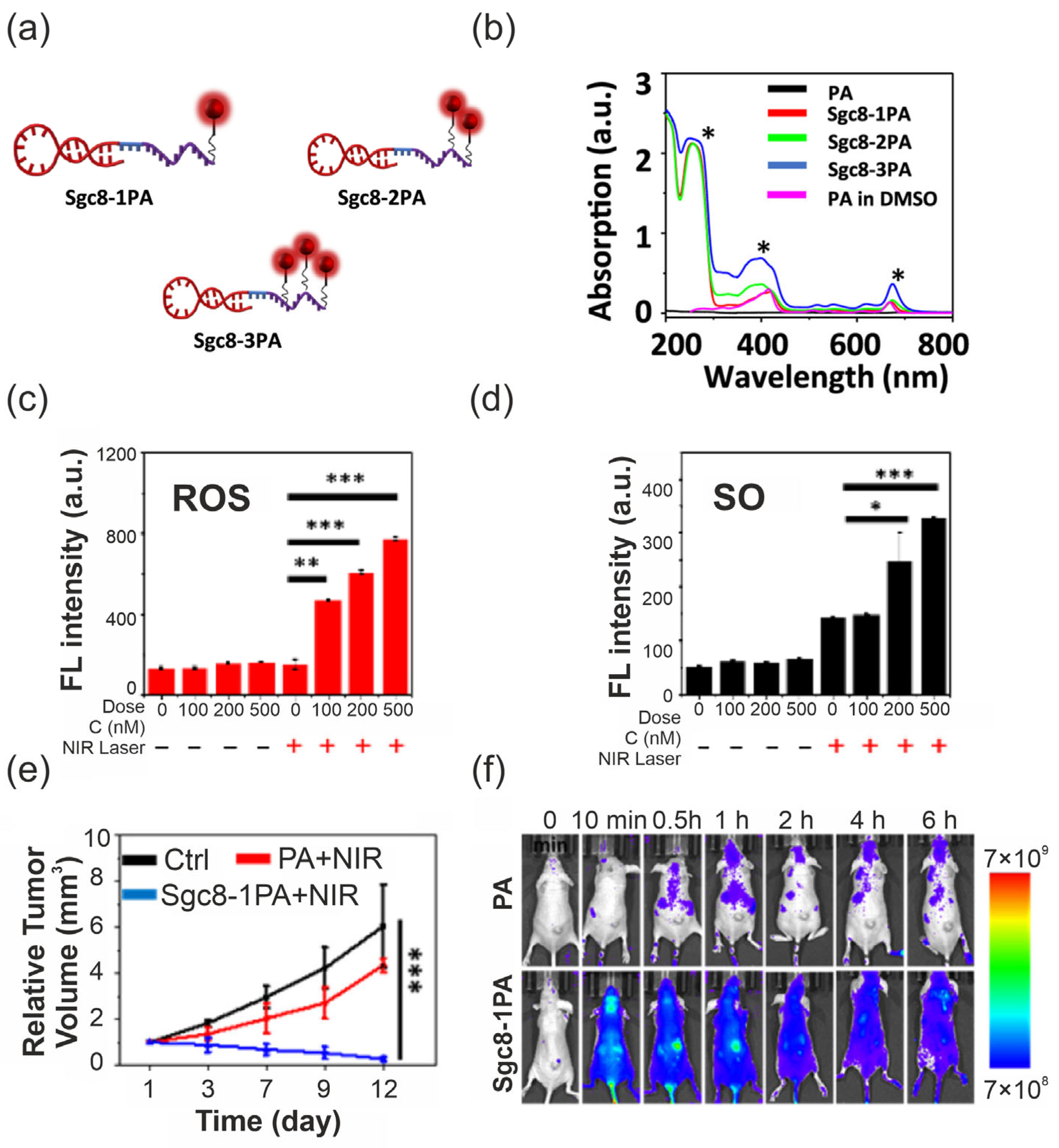

4.2. Aptamers

4.3. Vitamins and Coenzymes

4.4. Amino Acids

4.5. Peptides

| Peptide | Photosensitizer | Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPC3-targeting peptide | Chlorin e6 | Human hepatocellular carcinoma | [166] |

| (Lys)5 | Zn(II) phthalocyanine | Bacterial Skin Infections | [167] |

| Human hepatocellular carcinoma | |||

| cRGD | Si(IV) phthalocyanine | Human glioblastoma | [168] |

| Human prostate carcinoma | |||

| Human prostate adenocarcinoma | |||

| Human epidermoid carcinoma | |||

| P-DBOC | Chlorin e6 | Human cervical cancer | [165] |

| Cyclic polymyxin-derived peptide (PMBN) | Chlorin e6 | Gram-negative bacterial infections | [169] |

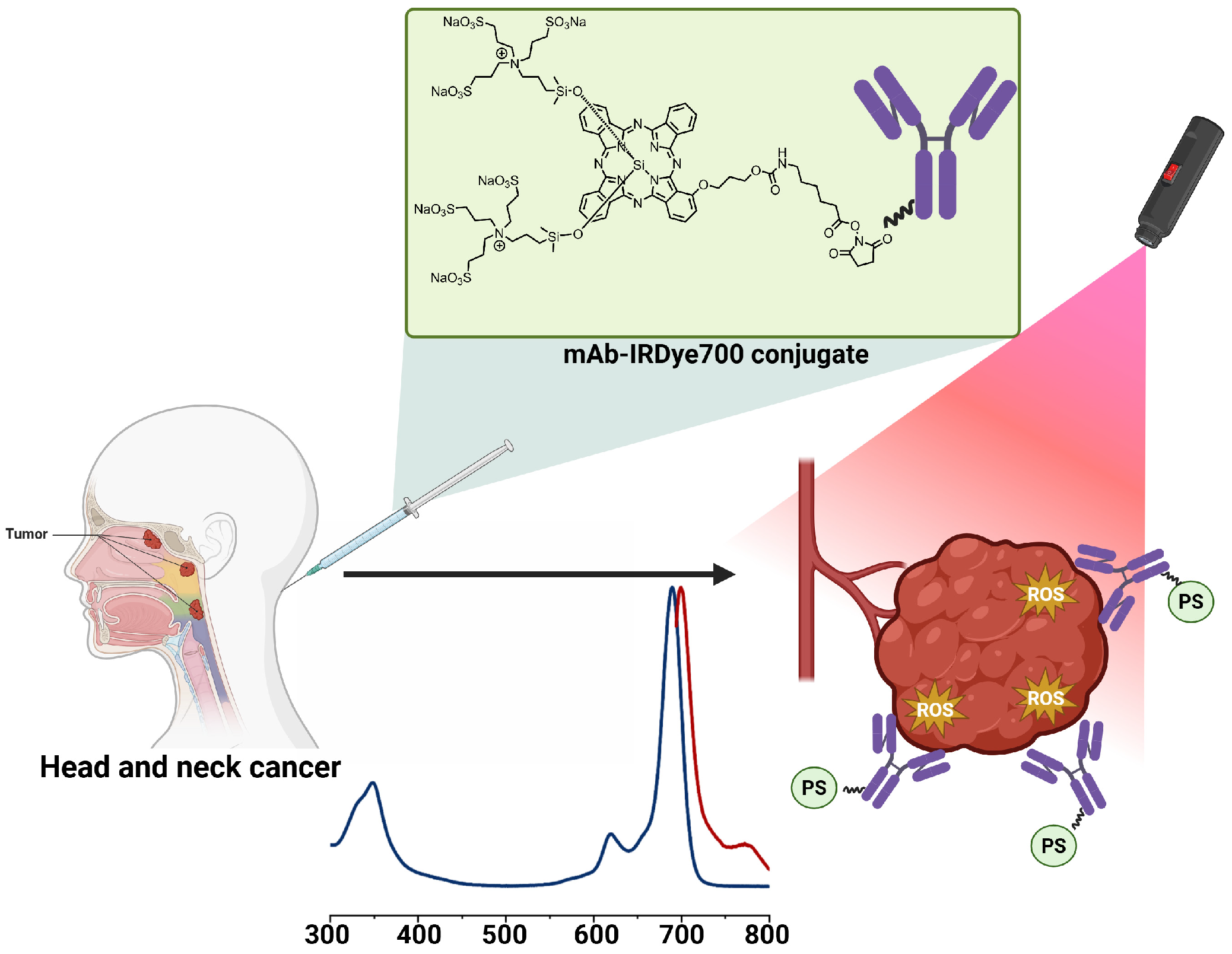

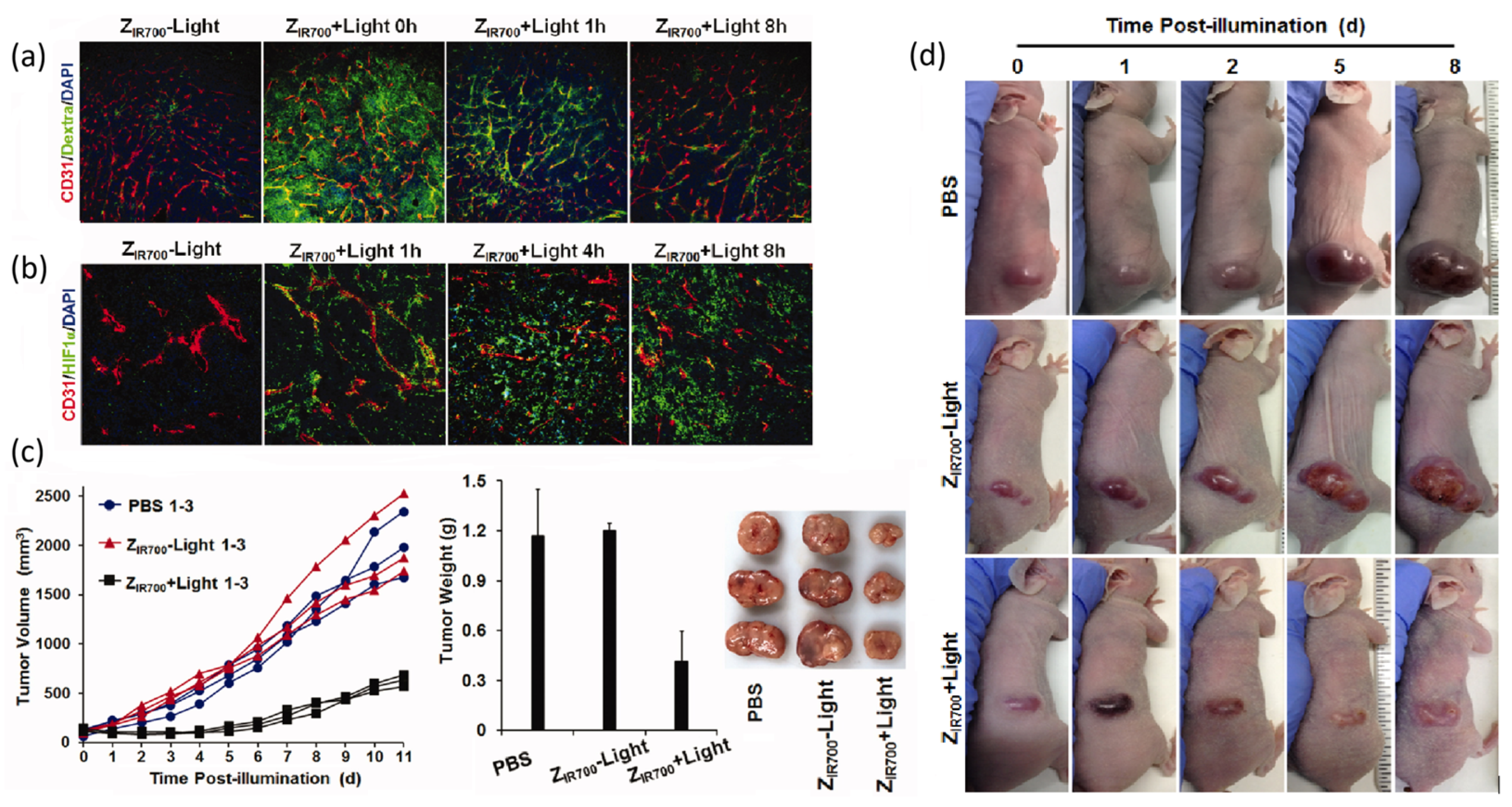

4.6. Proteins, Antibodies, and Affibodies

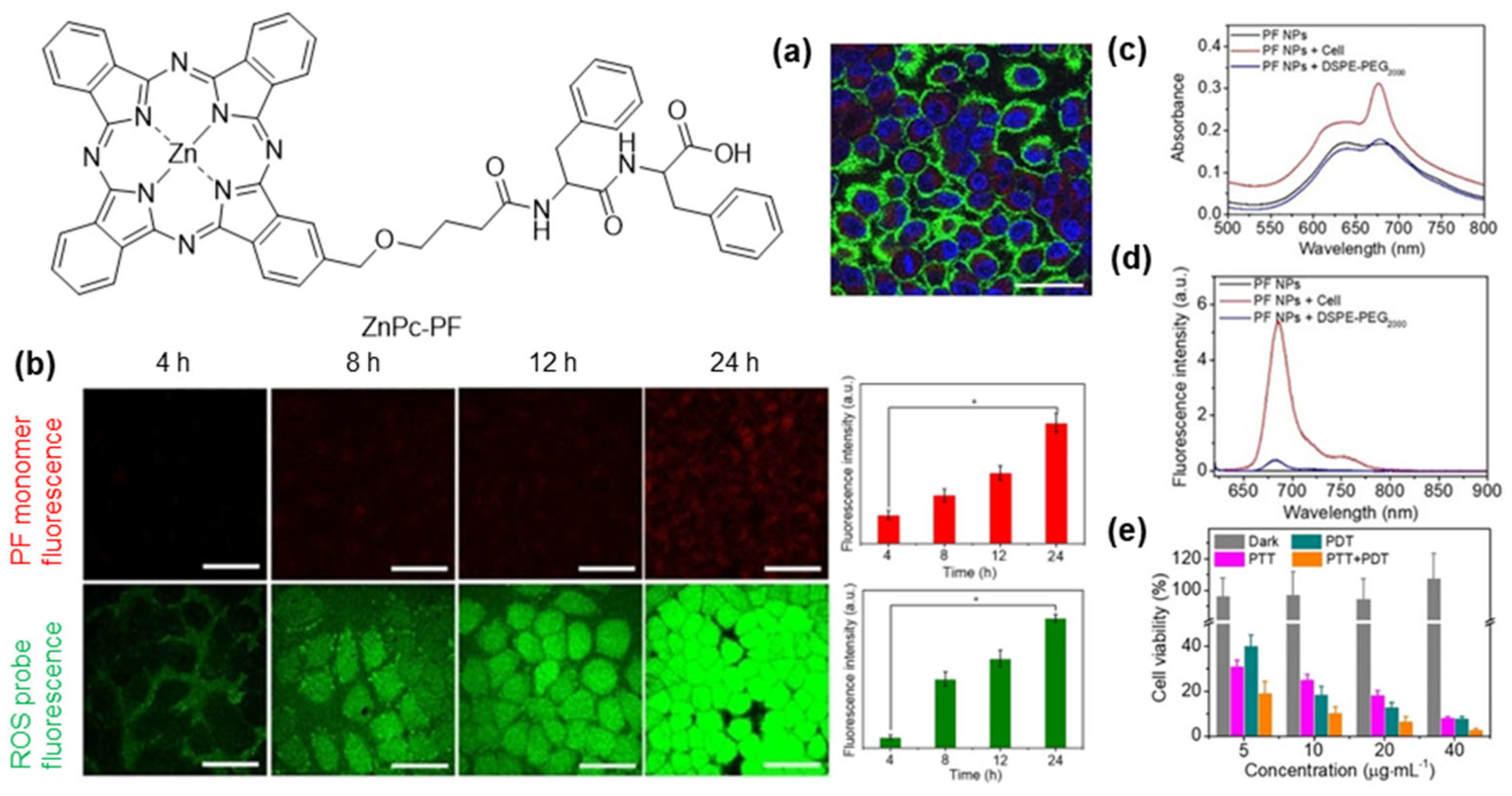

4.7. Self-Assembling Aggregates and Supramolecular Photosensitizer Systems

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two dimensional |

| 3D | Three dimensional |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BL-PDT | Bioluminescence-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy |

| BODIPY | 4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene |

| CALR | Calreticulin |

| CCR5 | Chemokine Receptor Type 5 |

| CCR7 | Chemokine Receptor Type 7 |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| CPPs | Cell Penetrating Peptides |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes |

| DAMPs | Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| DCs | Dendritic Cells |

| DLI | Drug to Light Interval |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| EPR | Enhanced Permeability and Retention |

| F4BMet | 5,10,15,20-tetrakis-[2′,3′,5′,6′-tetrafluoro-4′-methanesulfamoyl)phenyl] bacteriochlorin |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| FR | Folate receptor |

| GLUTs | Glucose Transporter |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HMGB1 | High-Mobility Group Box 1 |

| HSA | Human Serum Albumin |

| HSP70 | Heat Shock Protein 70 |

| ICD | Immunogenic Cell Death |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase |

| NK | Natural Killer Cells |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| NIR-II | Second Near-Infrared Window (1000–1700 nm) |

| NIR-IIa | Sub-window of NIR-II (1300–1400 nm) |

| OoC | Organ on chip |

| PA | Pyropheophorbide-a |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| PIT | Photoimmunotherapy |

| PpIX | Protoporphyrin IX |

| PS/PSs | Photosensitizer/Photosensitizers |

| RNI | Reactive Nitrogen Intermediates |

| RONS | Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SBCS | Symmetry-Breaking Charge Separation |

| SELEX | Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment |

| TME | Tumour Microenvironment |

References

- Ribas, A.; Wolchok, J.D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018, 359, 1350–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; Gettinger, S.N.; Smith, D.C.; McDermott, D.F.; Powderly, J.D.; Carvajal, R.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Atkins, M.B.; et al. Safety, Activity, and Immune Correlates of Anti–PD-1 Antibody in Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucelik, B.; Sułek, A.; Barzowska, A.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Recent advances in strategies for overcoming hypoxia in photodynamic therapy of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, 492, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg Effect: The Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Guo, L.; Overholser, J.; Wang, X. Mitochondrial VDAC1: A Potential Therapeutic Target of Inflammation-Related Diseases and Clinical Opportunities. Cells 2022, 11, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, W.; Xing, D. Recent advances in biotin-based therapeutic agents for cancer therapy. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 1812–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.; Stein, C.A. Antisense Oligonucleotides: Basic Concepts and Mechanisms. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002, 1, 347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Röth, A.; Harley, C.B.; Baerlocher, G.M. Imetelstat (GRN163L)—Telomerase-Based Cancer Therapy. In Small Molecules in Oncology; Martens, U.M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kyte, J.A. Cancer vaccination with telomerase peptide GV1001. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 18, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrilovich, D.I. INGN 201 (Advexin®): Adenoviral p53 gene therapy for cancer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2006, 6, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-W.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, M.J.; Chandler, L.A.; Lin, H.; et al. The First Approved Gene Therapy Product for Cancer Ad-p53 (Gendicine): 12 Years in the Clinic. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Élez, E.; Kocáková, I.; Höhler, T.; Martens, U.M.; Bokemeyer, C.; Van Cutsem, E.; Melichar, B.; Smakal, M.; Csőszi, T.; Topuzov, E.; et al. Abituzumab combined with cetuximab plus irinotecan versus cetuximab plus irinotecan alone for patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: The randomised phase I/II POSEIDON trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.A.; Cunningham, D.; Metges, J.P.; Van Cutsem, E.; Wainberg, Z.; Elboudwarej, E.; Lin, K.W.; Turner, S.; Zavodovskaya, M.; Inzunza, D.; et al. Randomized, open-label, phase 2 study of andecaliximab plus nivolumab versus nivolumab alone in advanced gastric cancer identifies biomarkers associated with survival. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

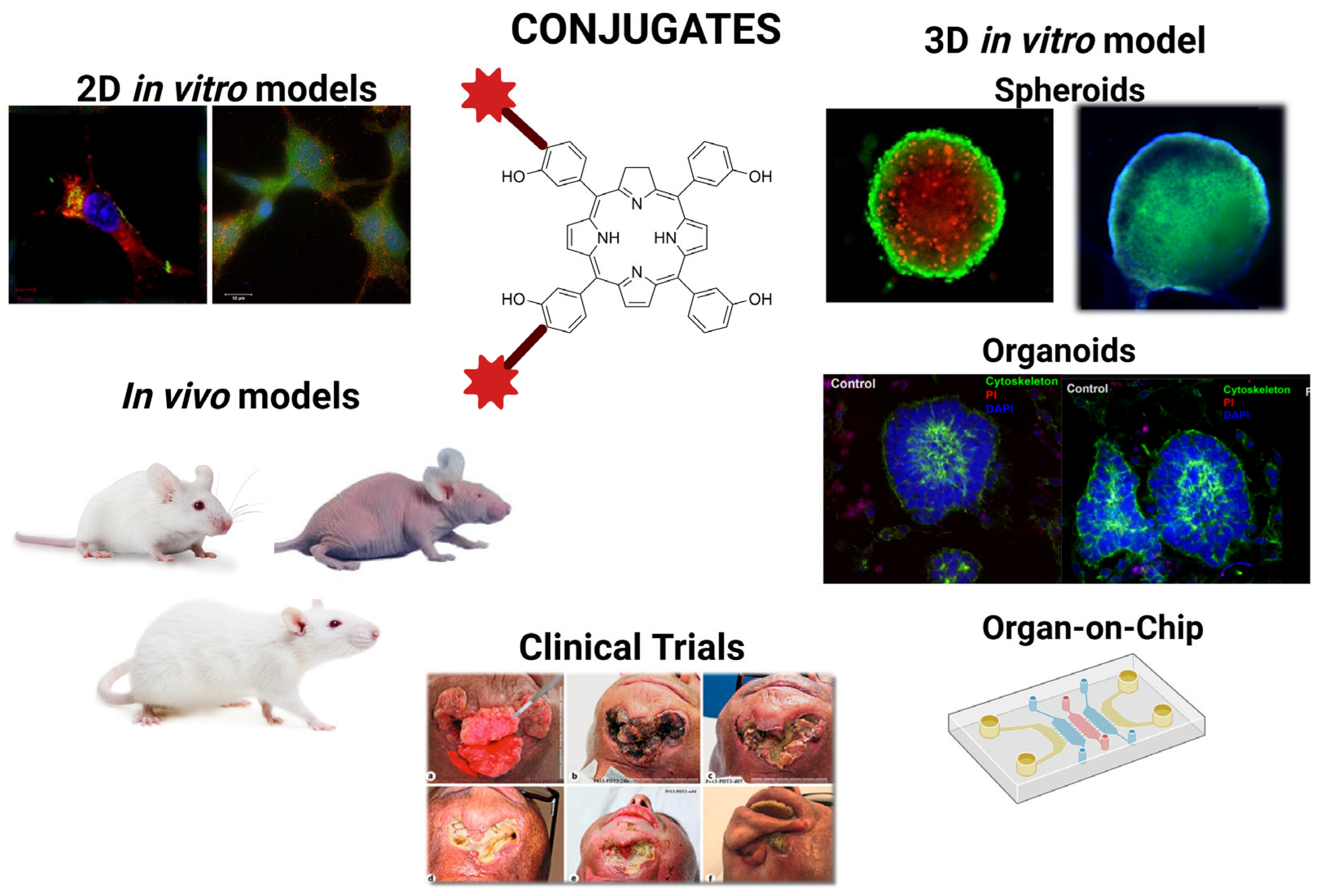

- Obaid, G.; Bano, S.; Mallidi, S.; Broekgaarden, M.; Kuriakose, J.; Silber, Z.; Bulin, A.-L.; Wang, Y.; Mai, Z.; Jin, W.; et al. Impacting Pancreatic Cancer Therapy in Heterotypic in vitro Organoids and in vivo Tumors with Specificity-Tuned, NIR-Activable Photoimmunonanoconjugates: Towards Conquering Desmoplasia? Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 7573–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz de Moraes, E.; do Carmo Silva, L.; Santana de Curcio, J.; Graça, A.M.; Batista, A.A.; Silveira Lacerda, E.d.P.; Gonçalves, P.J. Palladium(II)-Complexed meso-Tetra(4-pyridyl)porphyrin: Photodynamic Efficacy in 3D Pancreatic Cancer Models. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 53564–53571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, D.; Humblet, Y.; Siena, S.; Khayat, D.; Bleiberg, H.; Santoro, A.; Bets, D.; Mueser, M.; Harstrick, A.; Verslype, C.; et al. Cetuximab Monotherapy and Cetuximab plus Irinotecan in Irinotecan-Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, K.; Rogalska, A.; Marczak, A. Folate receptor alpha—A secret weapon in ovarian cancer treatment? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolin, K.; Synold, T.W.; Lara, P.; Frankel, P.; Lacey, S.F.; Quinn, D.I.; Baratta, T.; Dutcher, J.P.; Xi, B.; Diamond, D.J.; et al. Oblimersen and α-interferon in metastatic renal cancer: A phase II study of the California Cancer Consortium. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 133, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Shi, M.; Jie, F.; Bai, Y.; Shen, P.; Yu, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, C.; Tao, M.; Wang, Z.; et al. Phase III study of dulanermin (recombinant human tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand/Apo2 ligand) combined with vinorelbine and cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Investig. New Drugs 2018, 36, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N.; Hillan, K.J.; Novotny, W. Bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 333, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.; Lindley, C. Bevacizumab: An angiogenesis inhibitor for the treatment of solid malignancies. Clin. Ther. 2006, 28, 1779–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.W.; Grippon, S.; Kirkpatrick, P. Aflibercept. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markham, A.; Patel, T. Siltuximab: First Global Approval. Drugs 2014, 74, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

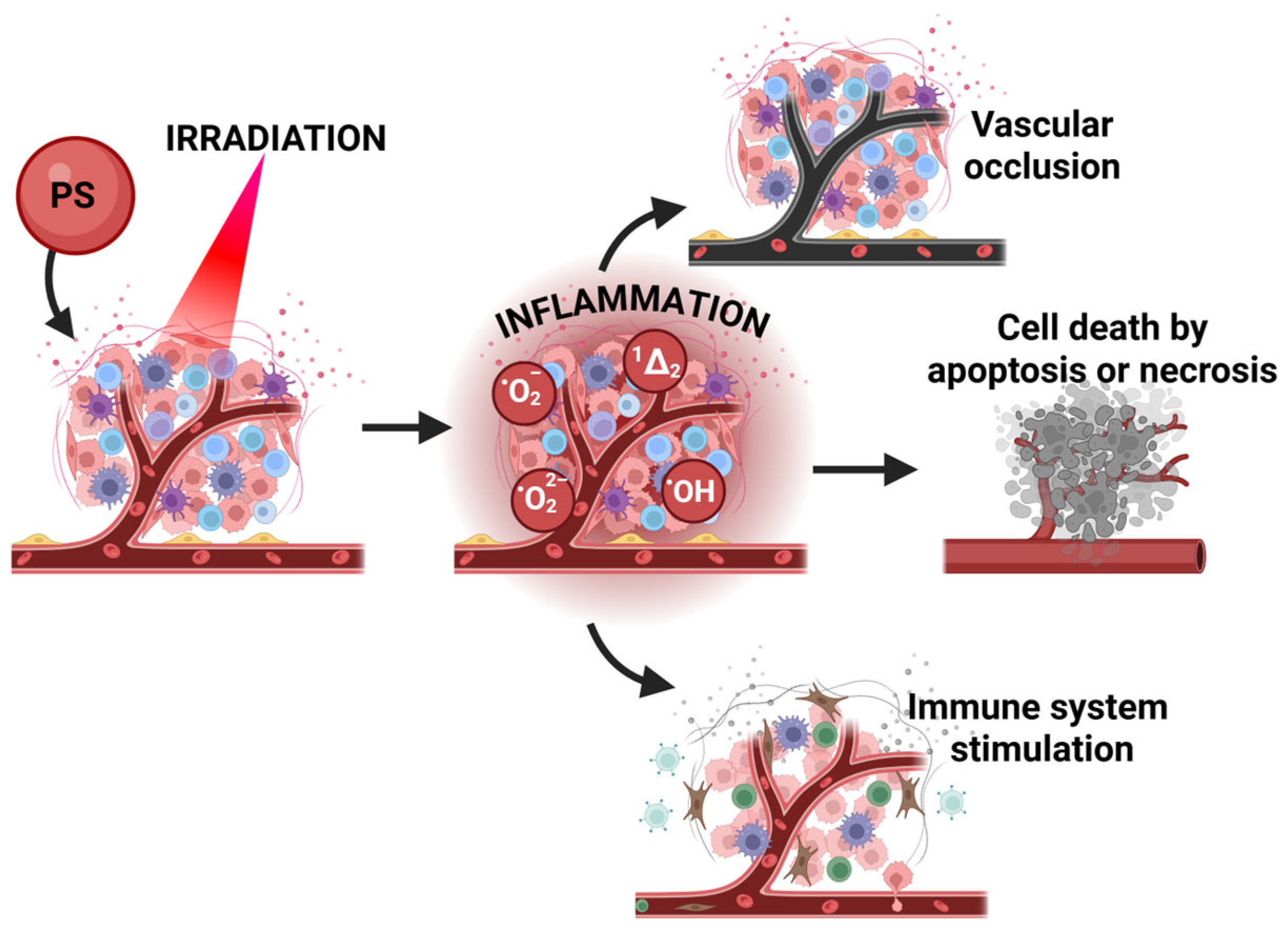

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K.A.; Foster, T.H.; Girotti, A.W.; Gollnick, S.O.; Hahn, S.M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: An update. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowski, J.M.; Arnaut, L.G. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) of cancer: From local to systemic treatment. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 1765–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.B.; Gomes-da-Silva, L.C.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Arnaut, L.G. Elimination of primary tumours and control of metastasis with rationally designed bacteriochlorin photodynamic therapy regimens. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 1822–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, J.F.; Liu, T.W.; Chen, J.; Zheng, G. Activatable photosensitizers for imaging and therapy. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2839–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucelik, B.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Photodynamic inactivation (PDI) as a promising alternative to current pharmaceuticals for the treatment of resistant microorganisms. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 79, pp. 65–108. [Google Scholar]

- Teles, A.V.; Oliveira, T.M.; Bezerra, F.C.; Alonso, L.; Alonso, A.; Borissevitch, I.E.; Gonçalves, P.J.; Souza, G.R. Photodynamic inactivation of Bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BoHV-1) by porphyrins. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

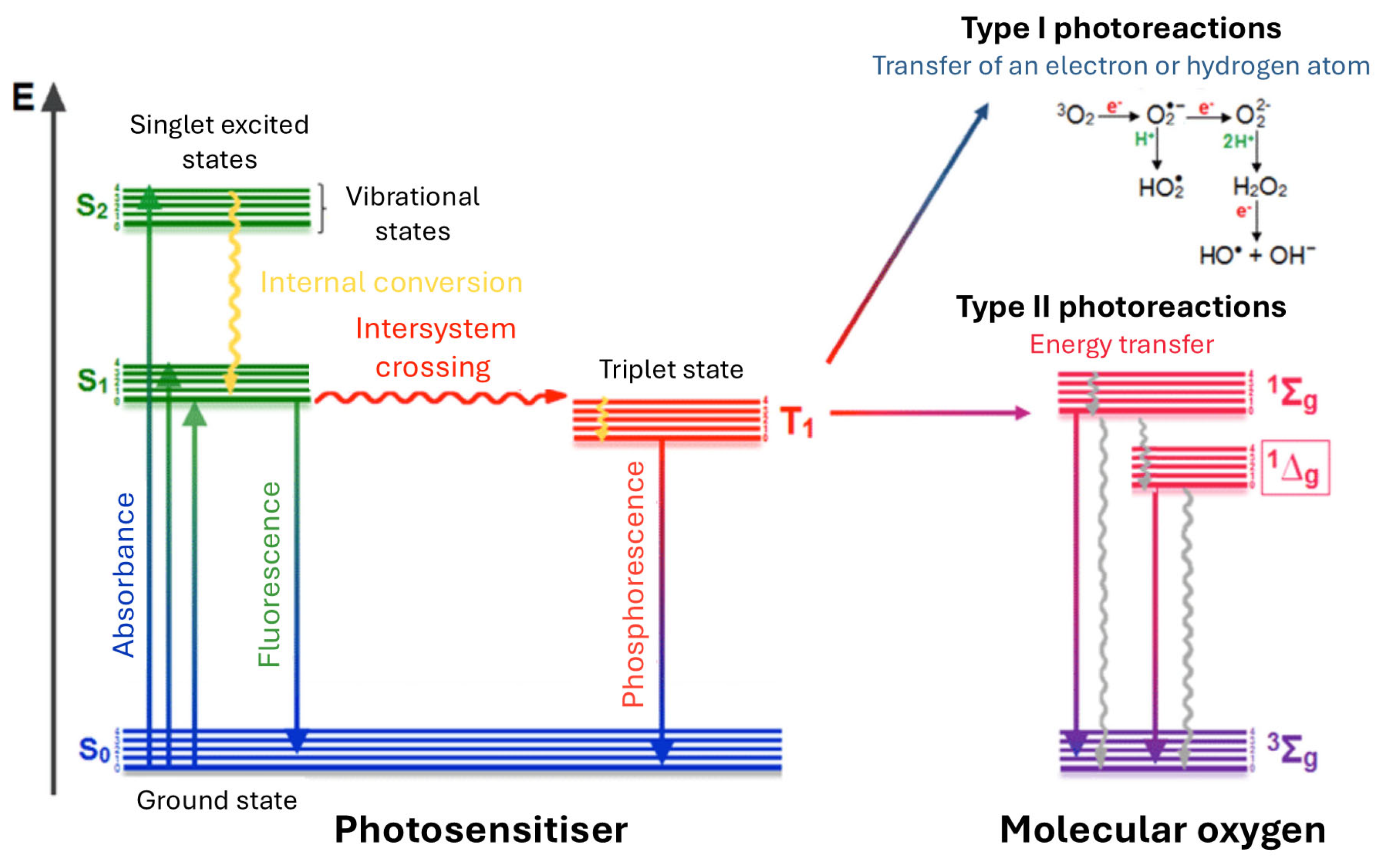

- Dąbrowski, J.M. Reactive oxygen species in photodynamic therapy: Mechanisms of their generation and potentiation. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 70, pp. 343–394. [Google Scholar]

- Pucelik, B.; Paczyński, R.; Dubin, G.; Pereira, M.M.; Arnaut, L.G.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Correction: Properties of halogenated and sulfonated porphyrins relevant for the selection of photosensitizers in anticancer and antimicrobial therapies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułek, A.; Pucelik, B.; Kobielusz, M.; Barzowska, A.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Photodynamic inactivation of bacteria with porphyrin derivatives: Effect of charge, lipophilicity, ROS generation, and cellular uptake on their biological activity in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.S.; Arnaut, Z.A.; Mata, A.I.; Pucelik, B.; Barzowska, A.; da Silva, G.J.; Pereira, M.M.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Arnaut, L.G. Efficient and selective, in vitro and in vivo, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy with a dicationic chlorin in combination with KI. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 3368–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucelik, B.; Sułek, A.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Bacteriochlorins and their metal complexes as NIR-absorbing photosensitizers: Properties, mechanisms, and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 416, 213340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, J.M.; Pucelik, B.; Regiel-Futyra, A.; Brindell, M.; Mazuryk, O.; Kyzioł, A.; Stochel, G.; Macyk, W.; Arnaut, L.G. Engineering of relevant photodynamic processes through structural modifications of metallotetrapyrrolic photosensitizers. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 325, 67–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułek, A.; Pucelik, B.; Kobielusz, M.; Łabuz, P.; Dubin, G.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Surface modification of nanocrystalline TiO2 materials with sulfonated porphyrins for visible light antimicrobial therapy. Catalysts 2019, 9, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, J.M.; Pucelik, B.; Pereira, M.M.; Arnaut, L.G.; Macyk, W.; Stochel, G. New hybrid materials based on halogenated metalloporphyrins for enhanced visible light photocatalysis. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 93252–93261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malec, D.; Warszyńska, M.; Repetowski, P.; Siomchen, A.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Enhancing visible-light photocatalysis with Pd (II) porphyrin-based TiO2 hybrid nanomaterials: Preparation, characterization, ROS generation, and photocatalytic activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 7819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Pucelik, B.; Międzybrodzka, A.; Sieroń, A.R.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Photodynamic therapy as an alternative to antibiotic therapy for the treatment of infected leg ulcers. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 23, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, N.S.; Fedotova, E.A.; Jankovic, P.; Gribova, G.P.; Nyuchev, A.V.; Fedorov, A.Y.; Otvagin, V.F. Enhancing Precision in Photodynamic Therapy: Innovations in Light-Driven and Bioorthogonal Activation. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, C.; Schmidt, R. Physical mechanisms of generation and deactivation of singlet oxygen. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1685–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, C.S. Definition of type I and type II photosensitized oxidation. Photochem. Photobiol. 1991, 54, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, R.W.; Gamlin, J.N. A Compilation of Singlet Oxygen Yields from Biologically Relevant Molecules. Photochem. Photobiol. 1999, 70, 391–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, F.; Helman, W.P.; Ross, A.B. Rate constants for the decay and reactions of the lowest electronically excited singlet state of molecular oxygen in solution. An expanded and revised compilation. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1995, 24, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilby, P.R. Singlet oxygen: There is indeed something new under the sun. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3181–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.F.F.; Serpa, C.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Monteiro, C.J.P.; Formosinho, S.J.; Stochel, G.; Urbanska, K.; Simões, S.; Pereira, M.M.; Arnaut, L.G. Mechanisms of Singlet-Oxygen and Superoxide-Ion Generation by Porphyrins and Bacteriochlorins and their Implications in Photodynamic Therapy. Chem. A Eur. J. 2010, 16, 9273–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaut, L.G.; Pereira, M.M.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Silva, E.F.; Schaberle, F.A.; Abreu, A.R.; Rocha, L.B.; Barsan, M.M.; Urbańska, K.; Stochel, G. Photodynamic therapy efficacy enhanced by dynamics: The role of charge transfer and photostability in the selection of photosensitizers. Chem. A Eur. J. 2014, 20, 5346–5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, R.; Rocha, L.B.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Arnaut, L.G. Modulation of biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and photosensitivity with the delivery vehicle of a bacteriochlorin photosensi-tizer for photodynamic therapy. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucelik, B.; Arnaut, L.G.; Stochel, G.; Dabrowski, J.M. Design of Pluronic-based formulation for enhanced redaporfin-photodynamic therapy against pigmented melanoma. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22039–22055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.B.; Schaberle, F.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Simões, S.; Arnaut, L.G. Intravenous single-dose toxicity of redaporfin-based photodynamic therapy in rodents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 29236–29249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, A.F.; Pucelik, B.; Pereira, M.M.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Arnaut, L.G. Translating phototherapeutic indices from in vitro to in vivo photodynamic therapy with bacteriochlorins. Lasers Surg. Med. 2018, 50, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucelik, B.; Arnaut, L.G.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Lipophilicity of bacteriochlorin-based photosensitizers as a determinant for PDT optimization through the modulation of the inflammatory mediators. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-Y.; Lu, L.; Jeong, H.; Kim, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Yoon, J. Enhancing biosafety in photodynamic therapy: Progress and perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 7749–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.-H.; Li, P.-Y.; Huang, H.-H.; Feng, L.; Liu, S.-H.; Liu, X.; Bai, F.-Q. Porphyrin photosensitizer molecules as effective medicine candidates for photodynamic therapy: Electronic structure information aided design. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 29368–29383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierlich, P.; Mata, A.I.; Donohoe, C.; Brito, R.M.M.; Senge, M.O.; Gomes-da-Silva, L.C. Ligand-Targeted Delivery of Photosensitizers for Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, W.A.; Malik, A.H.; Hussain, A.; Alajmi, M.F.; Shreaz, S.; Kostova, I. Recent advances in metal complexes for the photodynamic therapy of cancer. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 13244–13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garapati, C.; Boddu, S.H.S.; Jacob, S.; Ranch, K.M.; Patel, C.; Babu, R.J.; Tiwari, A.K.; Yasin, H. Photodynamic therapy: A special emphasis on nanocarrier-mediated delivery of photosensitizers in antimicrobial therapy. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, P. Recent advancements and perspectives of photoresponsive inorganic nanomaterials for cancer phototherapy and diagnosis. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 15450–15475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Woźnicki, P.; Dynarowicz, K.; Aebisher, D. Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy of Brain Cancers—A Review. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warszyńska, M.; Repetowski, P.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Photodynamic therapy combined with immunotherapy: Recent advances and future research directions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 495, 215350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, N.; Sevilla, A. Current Advances in Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) and the Future Potential of PDT-Combinatorial Cancer Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Chen, J.; Qu, Y.; Luo, X.; Wang, W.; Zheng, X. Recent Advances in Porphyrin-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks for Synergistic Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucelik, B.; Barzowska, A.; Sułek, A.; Werłos, M.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Refining antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: Effect of charge distribution and central metal ion in fluorinated porphyrins on effective control of planktonic and biofilm bacterial forms. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2024, 23, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, Q. Triggering Immune System With Nanomaterials for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 878524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Su, S.; Gao, N.; Jing, J.; Zhang, X. A multifunctional oxygen-producing MnO2-based nanoplatform for tumor microenvironment-activated imaging and combination therapy in vitro. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 9943–9950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Quan, G.; Huang, Z.; Wu, C.; Pan, X. An oxygen-generating metal organic framework nanoplatform as a “synergy motor” for extricating dilemma over photodynamic therapy. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 5420–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q. Tumor Hypoxia: From Basic Knowledge to Therapeutic Implications; Seminars in cancer biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hompland, T.; Fjeldbo, C.S.; Lyng, H. Tumor hypoxia as a barrier in cancer therapy: Why levels matter. Cancers 2021, 13, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzykawska-Serda, M.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Arnaut, L.G.; Szczygieł, M.; Urbańska, K.; Stochel, G.; Elas, M. The role of strong hypoxia in tumors after treatment in the outcome of bacteriochlorin-based photodynamic therapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 73, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwicka, M.; Pucelik, B.; Gonet, M.; Elas, M.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Effects of photodynamic therapy with redaporfin on tumor oxygenation and blood flow in a lung cancer mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiche, J.; Brahimi-Horn, M.C.; Pouysségur, J. Tumour hypoxia induces a metabolic shift causing acidosis: A common feature in cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 771–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahimi-Horn, M.C.; Pouysségur, J. Hypoxia in cancer cell metabolism and pH regulation. Essays Biochem. 2007, 43, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, N.; Weng, H.; Rajora, M.A.; Zheng, G. Activatable photosensitizers: From fundamental principles to advanced designs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202423348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Tang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, T.; Deng, L.; Dai, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, N.; Liu, S.; Fan, Y. Responsive nanomedicine strategies achieve pancreatic cancer precise theranostics. Bioact. Mater. 2026, 55, 334–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ow, V.; Lin, Q.; Wong, J.H.M.; Sim, B.; Tan, Y.L.; Leow, Y.; Goh, R.; Loh, X.J. Understanding the interplay between pH and charges for theranostic nanomaterials. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 6960–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G.; Hao, G.; Sun, Y.; Cao, J. Strategies to improve photodynamic therapy efficacy by relieving the tumor hypoxia environment. NPG Asia Mater. 2021, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Wei, H.; Li, Q.; Su, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, K.Y.; Lv, W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.; Huang, W. Achieving efficient photodynamic therapy under both normoxia and hypoxia using cyclometalated Ru (ii) photosensitizer through type I photochemical process. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Cao, D. Recent advances in type I organic photosensitizers for efficient photodynamic therapy for overcoming tumor hypoxia. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 4600–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Lu, S.-B.; Li, C.; Chen, F.; Ni, J.-S.; Zha, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Kang, T.; Liu, C. Type I macrophage activator photosensitizer against hypoxic tumors. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 14773–14780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Xiao, J.; Duan, X. Hypoxia-responsive liposome enhances intracellular delivery of photosensitizer for effective photodynamic therapy. J. Control. Release 2025, 377, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, F.; Yao, Z.; Song, W.; Tang, Y.; Ping, Y.; Liu, B. Activatable type I photosensitizer with quenched photosensitization pre and post photodynamic therapy. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202307288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warszyńska, M.; Pucelik, B.; Vinagreiro, C.S.; Repetowski, P.; Barzowska, A.; Barczyk, D.; Schaberle, F.A.; Duque-Prata, A.; Arnaut, L.G.; Pereira, M.M.; et al. Better in the Near Infrared: Sulfonamide Perfluorinated-Phenyl Photosensitizers for Improved Simultaneous Targeted Photodynamic Therapy and Real-Time Fluorescence Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 50389–50406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, S.; Ouyang, Y.; Huang, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Tian, J. A supramolecular nanoplatform for imaging-guided phototherapies via hypoxia tumour microenvironment remodeling. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 11481–11489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, S.; Wu, X.; Li, B. Carbon dots as a novel photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy of cancer and bacterial infectious diseases: Recent advances. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Song, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Y. Tumour microenvironment-responsive nanoplatform based on biodegradable liposome-coated hollow MnO2 for synergistically enhanced chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy. J. Drug Target. 2022, 30, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, K.; Ogawa, M. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy and anti-cancer immunity. Int. Immunol. 2024, 36, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Saad, M.A.; Przygórzewska, A.; Woźnicki, P.; Aebisher, D. Latest Nanoparticles to Modulate Hypoxic Microenvironment in Photodynamic Therapy of Cervical Cancer: A Review of In Vivo Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaid, G.; Bano, S.; Thomsen, H.; Callaghan, S.; Shah, N.; Swain, J.W.R.; Jin, W.; Ding, X.; Cameron, C.G.; McFarland, S.A.; et al. Remediating Desmoplasia with EGFR-Targeted Photoactivable Multi-Inhibitor Liposomes Doubles Overall Survival in Pancreatic Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, G.; Chambrier, I.; Cook, M.J.; Russell, D.A. Cancer targeting with biomolecules: A comparative study of photodynamic therapy efficacy using antibody or lectin conjugated phthalocyanine-PEG gold nanoparticles. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, N.E.M.; Dhingra, S.; Jois, S.D.; Vicente, M.d.G.H. Molecular Targeting of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR). Molecules 2021, 26, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.M.; Sable, R.; Singh, S.; Vicente, M.G.H.; Jois, S.D. Peptide ligands for targeting the extracellular domain of EGFR: Comparison between linear and cyclic peptides. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2018, 91, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Sun, W.; Du, J.; Fan, J.; Peng, X. Immuno-photodynamic therapy (IPDT): Organic photosensitizers and their application in cancer ablation. JACS Au 2023, 3, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Szoo, M.J.; van Bergen, T.D.; Seppelin, A.; Oh, J.; Saad, M.A. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy: Mechanisms, applications, and future perspectives in cancer research. Antib. Ther. 2025, 8, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, J.; Meng, C.; Feng, F. Recent advances for enhanced photodynamic therapy: From new mechanisms to innovative strategies. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 12234–12257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaydin, G.; Gedik, M.E.; Ayan, S. Photodynamic Therapy—Current Limitations and Novel Approaches. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 691697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.L.; Oliveira, J.; Monteiro, E.; Santos, J.; Sarmento, C. Treatment of head and neck cancer with photodynamic therapy with redaporfin: A clinical case report. Case Rep. Oncol. 2018, 11, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

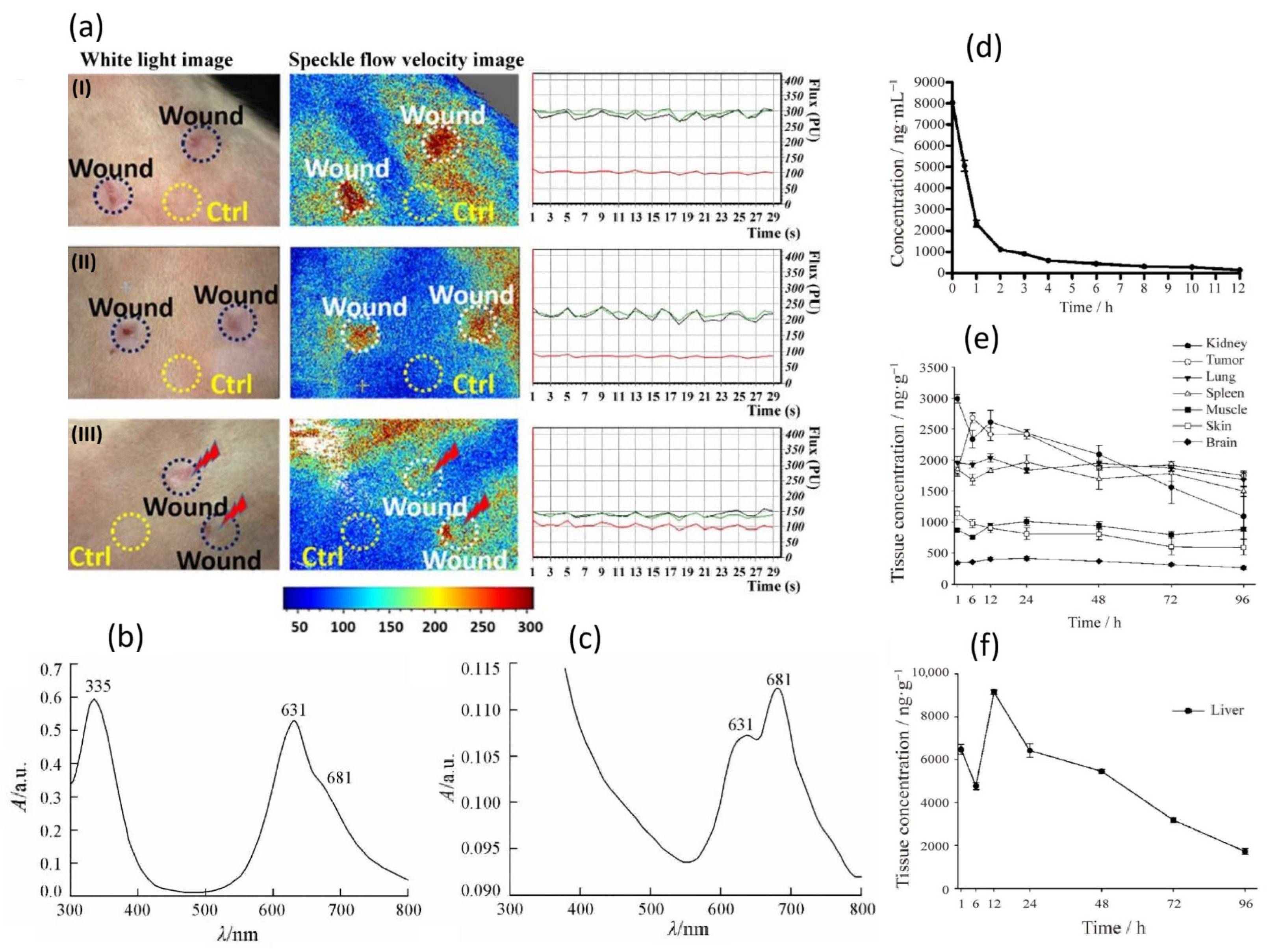

- Repetowski, P.; Warszynska, M.; Kostecka, A.; Pucelik, B.; Barzowska, A.; Emami, A.; İşci, U.; Dumoulin, F.; Dabrowski, J.M. Synthesis, photo-characterizations, and pre-clinical studies on advanced cellular and animal models of zinc (II) and platinum (II) sulfonyl-substituted phthalocyanines for enhanced vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 48937–48954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariño-Ocampo, N.; Dibona-Villanueva, L.; Escobar-Álvarez, E.; Guerra-Díaz, D.; Zúñiga-Núñez, D.; Fuentealba, D.; Robinson-Duggon, J. Recent Photosensitizer Developments, Delivery Strategies and Combination-based Approaches for Photodynamic Therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023, 99, 469–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vale, N.; Ramos, R.; Cruz, I.; Pereira, M. Application of Peptide-Conjugated Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Cancer Therapy: A Review. Organics 2024, 5, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.J.; Havrylyuk, D.; Hachey, A.C.; Heidary, D.K.; Glazer, E.C. Photodynamic therapy photosensitizers and photoactivated chemotherapeutics exhibit distinct bioenergetic profiles to impact ATP metabolism. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączyńska, J.; Da Pieve, C.; Burley, T.A.; Raes, F.; Shah, A.; Saczko, J.; Harrington, K.J.; Kramer-Marek, G. Immunomodulatory activity of IR700-labelled affibody targeting HER2. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichail, L.; Koch, L.S.; Veerman, D.; Broersen, K.; van der Meer, A.D. Organoids-on-a-chip: Microfluidic technology enables culture of organoids with enhanced tissue function and potential for disease modeling. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1515340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetowski, P.; Warszyńska, M.; Dąbrowski, J.M. NIR-activated multifunctional agents for the combined application in cancer imaging and therapy. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 336, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, L.; Bedia, C.; Diao, D.; Mosteiro, A.; Ferrés, A.; Stanzani, E.; Martínez-Soler, F.; Tortosa, A.; Pineda, E.; Aldecoa, I.; et al. Preclinical Studies with Glioblastoma Brain Organoid Co-Cultures Show Efficient 5-ALA Photodynamic Therapy. Cells 2023, 12, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosteiro, A.; Diao, D.; Bedia, C.; Pedrosa, L.; Caballero, G.A.; Aldecoa, I.; Mallo, M.; Solé, F.; Sevilla, A.; Ferrés, A.; et al. A Murine Model of Glioblastoma Initiating Cells and Human Brain Organoid Xenograft for Photodynamic Therapy Testing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, A.; Glasow, A.; Nürnberger, S.; Weimann, A.; Telemann, L.; Stolzenburg, J.U.; Neuhaus, J.; Berndt-Paetz, M. Ionizing radiation and photodynamic therapy lead to multimodal tumor cell death, synergistic cytotoxicity and immune cell invasion in human bladder cancer organoids. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2025, 51, 104459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Ma, D. Self-assembled phthalocyanine-based nano-photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy for hypoxic tumors. Mater. Chem. Front. 2024, 8, 3877–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, N.; Sadiq, A.; Ogaly, H.A.; Mughal, E.U. Phthalocyanine-nanoparticle conjugates for enhanced cancer photodynamic therapy. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 29890–29924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, M.; Lee, T.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, S.; Na, K. Synergistic Approach of Antibody-Photosensitizer Conjugate Independent of KRAS-Mutation and Its Downstream Blockade Pathway in Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2302374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Zhuo, Z.; Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Li, D.; Wan, Y.; et al. Recent Progress in Aptamer Discoveries and Modifications for Therapeutic Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 9500–9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhou, M. Targeted photodynamic therapy: Enhancing efficacy through specific organelle engagement. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1667812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xiong, T.; Peng, Q.; Du, J.; Sun, W.; Fan, J.; Peng, X. Self-reporting photodynamic nanobody conjugate for precise and sustainable large-volume tumor treatment. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadraeian, M.; da Cruz, E.F.; Boyle, R.W.; Bahou, C.; Chudasama, V.; Janini, L.M.R.; Diaz, R.S.; Guimarães, F.E.G. Photoinduced Photosensitizer–Antibody Conjugates Kill HIV Env-Expressing Cells, Also Inactivating HIV. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 16524–16534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H.; Nishie, H.; Tanaka, M.; Sasaki, M.; Nomoto, A.; Osaki, T.; Okamoto, Y.; Yano, S. Potential of Photodynamic Therapy Based on Sugar-Conjugated Photosensitizers. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, T.; Hibino, S.; Yokoe, I.; Yamaguchi, H.; Nomoto, A.; Yano, S.; Mikata, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Kataoka, H.; Okamoto, Y. A Basic Study of Photodynamic Therapy with Glucose-Conjugated Chlorin e6 Using Mammary Carcinoma Xenografts. Cancers 2019, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Wen, Y.; Tsushima, M.; Nakamura, H. Photodynamic Therapy by Glucose Transporter 1-Selective Light Inactivation. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 34685–34692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukeya, T.S.; Matshitse, R.; Mack, J.; Openda, Y.; Prinsloo, E.; Nyokong, T. Effects of central metals on sugar decorated tetrakis-(4-methylthiophenyl) porphyrin considered for use in photodynamic therapy. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2025, 54, 104658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

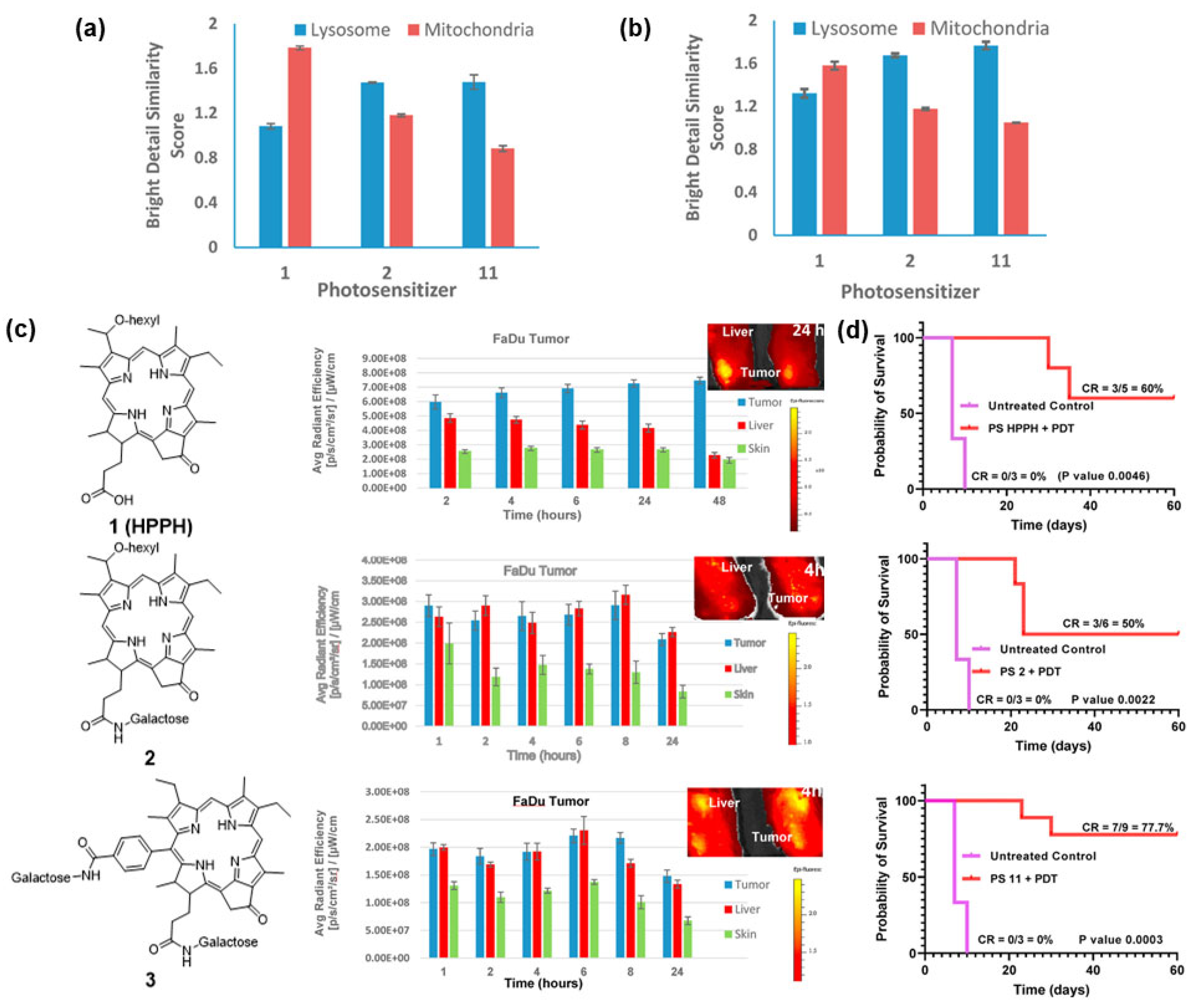

- Tracy, E.C.; Joshi, P.; Dukh, M.; Durrani, F.A.; Pandey, R.K.; Baumann, H. Galactosyl, alkyl, and acidic groups modify uptake and subcellular deposition of pyropheophorbide-a by epithelial tumor cells and determine photosensitizing efficacy. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2023, 27, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hageberg, I.U.; Arja, K.; Vindstad, B.E.; Bergvoll, J.K.; Gederaas, O.A.; Melø, T.-B.; Nilsson, K.P.R.; Lindgren, M. Photophysics of Glycosylated Ring-Fused Chlorin Complexes and Their Photosensitizing Effects on Cancer Cells. ChemPhotoChem 2023, 7, e202300028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, I.; Li, J.Z.; Shim, Y.K. Advance in photosensitizers and light delivery for photodynamic therapy. Clin. Endosc. 2013, 46, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Pandey, R.K. Porphyrin-carbohydrate conjugates: Impact of carbohydrate moieties in photodynamic therapy (PDT). Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Zheng, X.; Morgan, J.; Missert, J.R.; Liu, T.-H.; Shibata, M.; Bellnier, D.A.; Oseroff, A.R.; Henderson, B.W.; Dougherty, T.J. Purpurinimide carbohydrate conjugates: Effect of the position of the carbohydrate moiety in photosensitizing efficacy. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, B.S.; Özçeşmeci, M.; Koçyiğit, N.; Elgün, T.; Yurttaş, A.G.; Hamuryudan, E. Glycosylated zinc(II) phthalocyanine photosensitizer: Synthesis, photophysical properties and in vitro photodynamic activity on breast cancer cell line. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1295, 136688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Na, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, P. Different Targeting Ligands-Mediated Drug Delivery Systems for Tumor Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uruma, Y.; Sivasamy, L.; Yoong, P.M.Y.; Onuma, K.; Omura, Y.; Doe, M.; Osaki, M.; Okada, F. Synthesis and biological evaluation of glucose conjugated phthalocyanine as a second-generation photosensitizer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 3279–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, H.; Tian, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Teng, C.; Xie, K.; Yan, L. Galactose conjugated boron dipyrromethene and hydrogen bonding promoted J-aggregates for efficiently targeted NIR-II fluorescence assistant photothermal therapy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 612, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, J.; Bongo, A.M.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.; Cho, S.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, H.-J. BODIPY photosensitizers functionalized with mannose for fluorescence cell-imaging and photodynamic therapy. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1322, 140433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukh, M.; Cacaccio, J.; Durrani, F.A.; Kumar, I.; Watson, R.; Tabaczynski, W.A.; Joshi, P.; Missert, J.R.; Baumann, H.; Pandey, R.K. Impact of mono-and di-β-galactose moieties in in vitro/in vivo anticancer efficacy of pyropheophorbide-carbohydrate conjugates by photodynamic therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2022, 5, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ji, D.-K.; Yao, D.; Xiao, Z.; Tan, W. Molecular Engineering of Aptamer to Solubilize Hydrophobic Near-Infrared Photosensitizer for Enhanced Cancer Photodynamic Therapy. CCS Chem. 2024, 6, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, V.; Yen, P.Y.M.; Uruma, Y.; Lai, P.-S. Designing Synthetic Glycosylated Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 93, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, M.; Maeda, T.; Mashima, T.; Yano, S.; Sakuma, S.; Otake, E.; Morita, A.; Nakabayashi, Y. Syntheses and photodynamic properties of glucopyranoside-conjugated indium(III) porphyrins as a bifunctional agent. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2013, 17, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.M.A.; Miyagawa, K.; Fukui, N.; Onofre, M.; El Cheikh, K.; Morère, A.; Clément, S.; Gary-Bobo, M.; Richeter, S.; Shinokubo, H. d-Mannose-appended 5,15-diazaporphyrin for photodynamic therapy. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 8217–8222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, Y.; Kujirai, K.; Aoki, K.; Morita, M.; Masuda, M.; Zhang, L.; Kaixin, Z.; Nomoto, A.; Takahashi, T.; Tsuneoka, Y.; et al. Novel Photosensitizer β-Mannose-Conjugated Chlorin e6 as a Potent Anticancer Agent for Human Glioblastoma U251 Cells. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Liu, Y.; Ji, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, T.; Hong, G.; Zhao, Z. Galactose-modified zinc phthalocyanines for colon cancer photodynamic therapy. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2025, 55, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almammadov, T.; Elmazoglu, Z.; Atakan, G.; Kepil, D.; Aykent, G.; Kolemen, S.; Gunbas, G. Locked and Loaded: β-Galactosidase Activated Photodynamic Therapy Agent Enables Selective Imaging and Targeted Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme Cancer Cells. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 4284–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefe, A.D.; Pai, S.; Ellington, A. Aptamers as therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment: RNA Ligands to Bacteriophage T4 DNA Polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicki, S.; Pucelik, B.; Żyła, E.; Benedyk-Machaczka, M.; Gałan, W.; Golda, A.; Sochaj-Gregorczyk, A.; Kamińska, M.; Encarnação, J.C.; Chruścicka, B. Imaging of clear cell renal carcinoma with immune checkpoint targeting aptamer-based probe. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, T.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Cui, J.; Cao, Z.; Shangguan, D. Triplex-quadruplex structural scaffold: A new binding structure of aptamer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yameen, H.M.; Mahmood, I. Sittara, Nanocomposites of AS1411 and Novel Drug for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Res. 2025, 1, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Işıklan, N.; Hussien, N.A.; Türk, M. Multifunctional aptamer-conjugated magnetite graphene oxide/chlorin e6 nanocomposite for combined chemo-phototherapy. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 645, 128841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkuş, N.; Eksin, E.; Şahin, G.; Yildiz, E.; Bağda, E.; Altun, A.; Bağda, E.; Durmuş, M.; Erdem, A. The targeted photodynamic therapy of breast cancer with novel AS1411-indium(III) phthalocyanine conjugates. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1305, 137718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, Q.; Lv, Q.; Yan, C.; Li, P. Targeted Delivery of Catalase and Photosensitizer Ce6 by a Tumor-Specific Aptamer Is Effective against Bladder Cancer In Vivo. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 1705–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chornovolenko, K.; Koczorowski, T. Phthalocyanines Conjugated with Small Biologically Active Compounds for the Advanced Photodynamic Therapy: A Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chegeni, N.; Kadivar, F.; Saraei, P. Folic Acid, Folate Conjugates and Folate Receptors: Novel Applications in Imaging of Cancer and Inflammation-Related Conditions. Cancer Manag. Res. 2025, 17, 2821–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, H.; Guo, W.; Ma, Y.; Huang, W.; Hong, Z. Folic Acid–Conjugated Pyropheophorbide a as the Photosensitizer Tested for In Vivo Targeted Photodynamic Therapy. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 1482–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Deng, J.; Guo, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Wu, F. A folate-conjugated platinum porphyrin complex as a new cancer-targeting photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 5367–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowska, A.; Gryko, D. Vitamin B12 Derivatives Suitably Tailored for the Synthesis of Photolabile Conjugates. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 4940–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shell, T.A.; Lawrence, D.S. Vitamin B12: A tunable, long wavelength, light-responsive platform for launching therapeutic agents. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2866–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insińska-Rak, M.; Sikorski, M.; Wolnicka-Glubisz, A. Riboflavin and its derivates as potential photosensitizers in the photodynamic treatment of skin cancers. Cells 2023, 12, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Ma, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, S. Chlorin e6-Biotin Conjugates for Tumor-Targeting Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2021, 26, 7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Tang, S.; Hong, G.; Chen, W.; Chen, M.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Peng, X.; Song, F.; Zheng, W.-H. An unexpected strategy to alleviate hypoxia limitation of photodynamic therapy by biotinylation of photosensitizers. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, G.; Bobadova-Parvanova, P.; Smith, K.M.; Vicente, M.G.H. Syntheses and Investigations of Conformationally Restricted, Linker-Free α-Amino Acid–BODIPYs via Boron Functionalization. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 18030–18041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Xiao, J.; Gao, R.; Lin, F.; Liu, X. Porphyrin with amino acid moieties: A tumor photosensitizer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008, 172, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Dong, X.; Zhao, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, Q. Discovery of an amino acid-modified near-infrared Aza-BODIPY photosensitizer as an immune initiator for potent photodynamic therapy in melanoma. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 3616–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.; Xu, Z.; Hong, G.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, J.; Ji, H.; Liu, T. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro photodynamic antimicrobial activity of basic amino acid–porphyrin conjugates. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 92, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, M.d.G.H.; Smith, K.M. Amino Acid Derivatives of Chlorin-e6—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcik-Ercin, P.; Ekineker, G.; Salik, N.; Aydoğdu, B.; Yagci, T.; Göksel, M. Arginine mediated photodynamic therapy with silicon(IV) phthalocyanine photosensitizers. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 43, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wong, K.H.; Li, E.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, D.; Gao, J.; Chen, M. Co-delivery of dimeric camptothecin and chlorin e6 via polypeptide-based micelles for chemo-photodynamic synergistic therapy. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werłos, M.; Barzowska-Gogola, A.; Pucelik, B.; Repetowski, P.; Warszyńska, M.; Dąbrowski, J.M. One Change, Many Benefits: A Glycine-Modified Bacteriochlorin with NIR Absorption and a Type I Photochemical Mechanism for Versatile Photodynamic Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleinick, N.L.; Morris, R.L.; Belichenko, I. The role of apoptosis in response to photodynamic therapy: What, where, why, and how. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2002, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syuleyman, M.; Angelov, I.; Mitrev, Y.; Durmuş, M.; Mantareva, V. Cationic amino acids linked to Zn(II) phthalocyanines for photodynamic therapy: Synthesis and effects on physicochemical properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 396, 112555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Jin, S.; Yang, Z.; Yan, R.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Jin, Y. Cu2+-Pyropheophorbide a-Cystine Conjugate: Synergistic Photodynamic/Chemodynamic Therapy and Glutathione Depletion Improves the Antitumor Efficacy and Downregulates the Hypoxia-Inducing Factor. Bioconjug. Chem. 2023, 34, 1336–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Ji, C.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Cao, T.; Cheng, J.; Sun, R. Bioorthogonal reaction-mediated photosensitizer-peptide conjugate anchoring on cell membranes for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 13, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; He, S.; Sheng, C.; Dong, G. Smart glypican-3-targeting peptide–chlorin e6 conjugates for targeted photodynamic therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 116047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Chen, D.; Chen, N.; Huang, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, P.; et al. A Simple Phthalocyanine-Peptide Conjugate as Targeting Photosensitizer and Its Broad Applications in Health. Health Metab. 2024, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Pang, M.; Tan, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, K.; Wu, W.; Hong, Z. Potent peptide-conjugated silicon phthalocyanines for tumor photodynamic therapy. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Kong, X.; Li, H.; Ji, Y.; He, S.; Shi, Y.; Hu, H. Cyclic peptide conjugated photosensitizer for targeted phototheranostics of gram-negative bacterial infection. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 145, 107203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, M.; Yan, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y. Insight into the prospects for tumor therapy based on photodynamic immunotherapy. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobzev, D.; Semenova, O.; Tatarets, A.; Bazylevich, A.; Gellerman, G.; Patsenker, L. Antibody-guided iodinated cyanine for near-IR photoimmunotherapy. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 212, 111101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankarajan, E.; Tuchinsky, H.; Aviel-Ronen, S.; Bazylevich, A.; Gellerman, G.; Patsenker, L. Antibody guided activatable NIR photosensitizing system for fluorescently monitored photodynamic therapy with reduced side effects. J. Control. Release 2022, 343, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.S.; Khandave, P.Y.; Tiwatane, A.K.; Rawat, K.; Bhaumik, J.; Pande, A.H. Photosensitizer-Antibody Conjugates (PhotoBodies): Emerging Frontiers in the Field of Theranostics. Pharm. Res. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Shen, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Hong, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, S. Efficient Tumor-Targeted Photosensitizer Based on Nanobody-Coupled Pyropheophorbide-a for Precise Photodynamic Therapy of Tumors. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 3110–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniakas, A.; Gillenwater, A.M.; Cognetti, D.; Mifsud, M.J.; Ashraf, N.; Civantos, F.F.; Danesi, H.; Veresh, B.; Chen, S.-Y.E.; Dong, H.; et al. A phase 3 randomized study of ASP-1929 photoimmunotherapy in combination with pembrolizumab versus standard of care in locoregional recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, TPS6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Okada, T.; Okada, R.; Yasui, H.; Yamada, M.; Isobe, Y.; Nishinaga, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Koike, C.; Fukushima, R. Photoinduced Actin Aggregation Involves Cell Death: A Mechanism of Cancer Cell Cytotoxicity after Near-Infrared Photoimmunotherapy. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 8338–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jin, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, W.; Xing, Y.; Wang, F.; Hong, Z. Anti-HER2 affibody-conjugated photosensitizer for tumor targeting photodynamic therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Pantarat, N.; Suzuki, T.; Evdokiou, A. Near-Infrared Photoimmunotherapy Using a Small Protein Mimetic for HER2-Overexpressing Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulfo, L.; Costantini, P.E.; Di Giosia, M.; Danielli, A.; Calvaresi, M. EGFR-Targeted Photodynamic Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, H.; Qi, S.; Tang, X.; Zhao, S.; Bian, X.; Tian, B.; Zhang, H.; Wei, Y.; Jia, D.; et al. A novel EGFR-targeted photosensitizer for the theranostics of skin cancer. Int. J. Pharm. X 2025, 10, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, C.; Soma, S.; Quaye, M.; Talgatov, A.; Shafirstein, G.; Samkoe, K.; McFarland, S.; Obaid, G. Predicting head and neck tumor nodule responses to TLD1433 photodynamic therapy using the image-guided surgery probe ABY-029. Photochem. Photobiol. 2025, 101, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Tao, Z.; Yang, H.; Fan, Q.; Wei, D.; Wan, L.; Lu, X. PDGFRβ-specific affibody-directed delivery of a photosensitizer, IR700, is efficient for vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy of colorectal cancer. Drug Deliv. 2017, 24, 1818–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Hu, X.; Hu, H.; Wang, P.; Cai, J. Novel small 99mTc-labeled affibody molecular probe for PD-L1 receptor imaging. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1017737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Braga, M.C.; Da Pieve, C.; Szopa, W.; Starzetz, T.; Plate, K.H.; Kaspera, W.; Kramer-Marek, G. Immuno-PET Imaging of Tumour PD-L1 Expression in Glioblastoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Zhan, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lv, M.; Tang, X.; Guo, W.; Li, H.; Sun, L.; et al. ICG-labeled PD-L1-antagonistic affibody dimer for tumor imaging and enhancement of tumor photothermal-immunotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Jia, D.; Yuan, F.; Wang, F.; Wei, D.; Tang, X.; Tian, B.; Zheng, S.; Sun, R.; Shi, J.; et al. Her3-specific affibody mediated tumor targeting delivery of ICG enhanced the photothermal therapy against Her3-positive tumors. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 617, 121609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordà-Redondo, M.; Piqueras, A.; Castillo, A.; Fernández, P.L.; Bresolí-Obach, R.; Blay, L.; Julián Ibáñez, J.F.; Nonell, S. An antibody-photosensitiser bioconjugate overcomes trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 290, 117511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Guo, X.; Wang, S.; Wei, Z.; Huang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, T.C.; Huang, Z. Singlet oxygen in photodynamic therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandland, J.; Boyle, R.W. Photosensitizer Antibody–Drug Conjugates: Past, Present, and Future. Bioconjug. Chem. 2019, 30, 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hou, J.; Wan, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, L. Targeted photodynamic elimination of HER2 + breast cancer cells mediated by antibody–photosensitizer fusion proteins. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2025, 24, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, R.; Maruoka, Y.; Furusawa, A.; Inagaki, F.; Nagaya, T.; Fujimura, D.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. The Effect of Antibody Fragments on CD25 Targeted Regulatory T Cell Near-Infrared Photoimmunotherapy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2019, 30, 2624–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkune, N.W.; Abrahamse, H. The phototoxic effect of a gold-antibody-based nanocarrier of phthalocyanine on melanoma monolayers and tumour spheroids. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 19490–19504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Sivakumar, I.; Mironchik, Y.; Krishnamachary, B.; Wildes, F.; Barnett, J.D.; Hung, C.-F.; Nimmagadda, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Bhujwalla, Z.M.; et al. PD-L1 near Infrared Photoimmunotherapy of Ovarian Cancer Model. Cancers 2022, 14, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Gao, F.; Wu, G.; Li, J.; Sheng, C.; He, S.; Hu, H. Precise HER2 Protein Degradation via Peptide-Conjugated Photodynamic Therapy for Enhanced Breast Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2410778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekgaarden, M.; Anbil, S.; Bulin, A.-L.; Obaid, G.; Mai, Z.; Baglo, Y.; Rizvi, I.; Hasan, T. Modulation of redox metabolism negates cancer-associated fibroblasts-induced treatment resistance in a heterotypic 3D culture platform of pancreatic cancer. Biomaterials 2019, 222, 119421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Shuhe, Z.; Baoding, S.; Yihan, Z.; Guangming, J. Preparation of transferrin-modified IR820-loaded liposomes and its effect on photodynamic therapy of breast cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohlongo, M.; George, B.P.; Abrahamse, H. Applications of bioluminescence-mediated photodynamic therapy (BL-PDT) for the treatment of deep-seated tumours. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.; Huh, M.; Lee, S.J.; Koo, H.; Kwon, I.C.; Jeong, S.Y.; Kim, K. Photosensitizer-conjugated human serum albumin nanoparticles for effective photodynamic therapy. Theranostics 2011, 1, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linero-Artiaga, A.; Servos, L.-M.; Papadopoulos, Z.; Rodríguez, V.; Ruiz, J.; Karges, J. Conjugation of a cyclometalated Ir (III) complex to human serum albumin for oncosis-mediated photodynamic therapy. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 7068–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Kim, Y.; Youn, S.-Y.; Jeong, H.; Shirbhate, M.E.; Uhm, C.; Kim, G.; Nam, K.T.; Cha, S.-S.; Kim, K.M. Conversion of albumin into a BODIPY-like photosensitizer by a flick reaction, tumor accumulation and photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials 2025, 313, 122792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunin, D.A.; Martynov, A.G.; Gvozdev, D.A.; Gorbunova, Y.G. Phthalocyanine aggregates in the photodynamic therapy: Dogmas, controversies, and future prospects. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunin, D.A.; Akasov, R.A.; Martynov, A.G.; Stepanova, M.P.; Monich, S.V.; Tsivadze, A.Y.; Gorbunova, Y.G. Pivotal Role of the Intracellular Microenvironment in the High Photodynamic Activity of Cationic Phthalocyanines. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-Z.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.; Fu, S.; Wang, C.; Li, X. Modulation of phthalocyanine assembly morphology for photodynamic therapy. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 19596–19607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.N.M.; Desordi, J.C.; Ducas, E.S.A.; Chaves, O.A.; Carmo, M.E.G.; Patrocinio, A.O.T.; Iglesias, B.A.; Gonçalves, P.J. Insights into bovine serum albumin (BSA) photooxidation mediated by mono-cationic porphyrins with Pd(II), Pt(II), and Ru(II) bipyridyl complexes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2026, 472, 116793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Tang, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Ke, M.-R.; Zheng, B.-Y.; Huang, S.; et al. Phthalocyanine aggregates as semiconductor-like photocatalysts for hypoxic-tumor photodynamic immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; van Hest, J.C.; Xing, R.; Yan, X. Peptide self-assembly meets photodynamic therapy: From molecular design to antitumor applications. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 13841–13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Chang, R.; Xing, R.; Yan, X. Spatiotemporally coupled photoactivity of phthalocyanine–peptide conjugate self-assemblies for adaptive tumor theranostics. Chem. A Eur. J. 2019, 25, 13429–13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Selected Features of Tumour | Biomolecule | Example | Cancer Model | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune evasion | Monoclonal antibodies | Pembrolizumab Nivolumab Atezolizumab | Metastatic melanoma Non-small cell lung cancer | [1,2] |

| Energy metabolism dysfunction | Oligonucleotides Peptides Vitamins/cofactors | siRNA VDAC1-HK2 Biotin–chlorin e6 | Glioblastoma Breast cancer Solid tumours, hypoxic models | [4,5,6] |

| Immortality | Antisense oligonucleotides Peptide vaccines | Imetelstat GV1001 | Myelofibrosis | [7,8,9] |

| Resistance to proliferation-inhibiting signals | Gene therapy | Gendicine; Advexin | Sarcomas Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | [10,11] |

| Ability to metastasize | Monoclonal antibodies Peptides | Abituzumab Andecaliximab | Metastatic colorectal cancer Pancreatic cancer Gastric cancer | [12,13,14,15] |

| Unrestricted proliferation | Monoclonal antibodies Vitamins (folate ligands) | Trastuzumab Cetuximab Folic acid–PS conjugates | Breast cancer Colorectal cancer Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma FR-overexpressing cancers | [16,17] |

| Apoptosis escape | Antisense oligonucleotides Recombinant proteins | Oblimersen Dulanermin | Melanoma Chronic lymphocytic leukemia Non-small cell lung cancer | [18,19] |

| Increased angiogenesis | Monoclonal antibodies Fusion proteins | Bevacizumab Aflibercept | Metastatic colorectal cancer Glioblastoma Non-small cell lung cancer Renal cell carcinoma | [20,21,22] |

| Inflammation | Monoclonal antibodies | Siltuximab | Multiple myeloma Melanoma | [23] |

| Model Type | Description | Application in Biological Evaluation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting, binding models | Analysis of affinity, specificity, receptor binding, and competition assays after conjugation | Verification that the biomolecular ligand retains selectivity for target cells (flow cytometry, microscopy, blocking assays) | [110,111] |

| Photophysical/photochemical models | Measurement of ROS formation, singlet oxygen quantum yield, photobleaching resistance, and irradiation response | Assessment of whether conjugation preserves efficient ROS generation, photostability, and PDT potency | [101,112] |

| In vitro cytotoxicity models | Cellular viability assays under light vs. dark conditions; mechanistic studies of apoptosis/necrosis/autophagy | Determination of light-to-dark toxicity ratio, mechanistic pathways, and early therapeutic potential | [110,113] |

| Subcellular localization models | Confocal imaging, organelle-specific markers, and cell-fractionation studies | Linking intracellular localization (mitochondrial, lysosomal, membrane) to cytotoxic mechanism and conjugate performance | [110,112] |

| In vivo biodistribution, pharmacokinetic models | Optical imaging, PET/SPECT tracking, tumour retention analysis, clearance studies | Evaluation of selectivity in living organisms, systemic distribution, tumour accumulation, and clearance kinetics | [111] |

| In vivo efficacy models | Tumour growth inhibition, regression, survival studies, and immune profiling | Determination of therapeutic benefit relative to free PS; assessment of ICD | [101] |

| Safety, toxicology models | Haematology, liver/kidney function tests, histopathology, immunogenicity analysis | Defining the therapeutic window, off-target effects, systemic toxicity, and phototoxicity profile | [112] |

| Carbohydrate | Photosensitizer | Model | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-glucose | Zn(II) phthalocyanine | Mouse fibrosarcoma and a more advanced and aggressive stage of fibrosarcoma | [125] |

| In(III) 5, 10, 15, 20-tetraphenylporphyrin | Human melanoma COLO 679 cells | [130,131] | |

| Chlorin e6 | Mammary carcinoma cells | [115] | |

| D-mannose | 5,15-diazaporphyrin | Human breast cancer cells | [132] |

| Chlorin e6 | Human glioblastoma cells | [133] | |

| D-galactose | Zn(II) phthalocyanine | Colon cancer cells | [134] |

| 7-hydroxy-6-iodo-3H-phenoxazin-3-one | Human glioblastoma cells | [135] | |

| BODIPY derivative | Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells | [126] |

| Aptamer | Photosensitizer | Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AS1411 | Chlorin e6 | DMBA-induced mammary tumours | [141] |

| MUC1+Fe3O4@GO | Chlorin e6 | Human breast cancer cells | [142] |

| AS1411 | In(III) phthalocyanine | Human breast cancer cells | [143] |

| Sgc8 | Pyropheophorbide a | Human colorectal carcinoma | [129] |

| Amino Acid | Photosensitizer | Model | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine | Bacteriochlorin (F2BGly) | Breast and colon cancer cells | [161] |

| BODIPY | Laryngeal carcinoma cells | [154] | |

| Aspartic acid | Chlorin e6 | Cervical carcinoma cells Breast adenocarcinoma cells | [158,162] |

| Arginine | Zn(II) phthalocyanine | Cervical cancer cells | [163] |

| Si(IV) phthalocyanine | Cervical, breast, and liver cancer cells | [159] | |

| Cysteine | Cu(II) Pyropheophorbide-a | Murine breast cancer cells Human cervical carcinoma | [164] |

| Affibody | Photosensitizer | Model | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HER2-binding affibody | pyropheophorbide-a | Breast cancer | [177] |

| IRDye700DX | [178] | ||

| EGFR-binding affibody | Temoporfin Chlorin e6 Verteporfin Indocyanine green IRDye800CW | Breast cancer Glioblastoma Head and neck cancer Skin cancer | [179,180,181] |

| PDGFRβ-binding affibody | IRDye700DX | Tumour blood vessels of colorectal cancer | [182] |

| (vascular-targeted PDT) | |||

| PD-L1-binding affibody | ICG | Glioblastoma multiforme brain tumours | [178,183,184,185] |

| HER3-binding affibody | ICG | HER3-positive MCF7 and LS174T cells | [186] |

| Antibody | Photosensitizer | Model | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trastuzumab | IRDye700DX | Breast cancer | [187,189] |

| Chlorin e6 | Stomach cancers | [190] | |

| Cetuximab | Chlorin e6 | Colorectal cancer | [109,112,191] |

| IRDye700DX | Head and neck cancer | ||

| Anti-MIA Ab | Zn(II) PcS4 | Melanoma | [192] |

| Anti-PD-L1 Ab | IRDye700DX | Ovarian cancer | [193] |

| Anti-HER2 Ab | Pyropheophorbide-a | Breast cancer | [194] |

| Protein | Photosensitizer | Model | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human serum albumin | Chlorin e6 | Human colon cancer | [198,199,200] |

| Cyclometalated Ir(III) complex | Human breast cancer | ||

| BODIPY-like PS | Human liver cancer | ||

| Transferrin | Zn(II) PcN4 IR820 | Human breast cancer | [196] |

| Luciferase | Chlorin e6 | Human breast cancer “deep-seated tumours” | [197] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Płaskonka, D.M.; Barczyk, D.; Repetowski, P.; Warszyńska, M.; Dąbrowski, J.M. Biomolecule–Photosensitizer Conjugates: A Strategy to Enhance Selectivity and Therapeutic Efficacy in Photodynamic Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010065

Płaskonka DM, Barczyk D, Repetowski P, Warszyńska M, Dąbrowski JM. Biomolecule–Photosensitizer Conjugates: A Strategy to Enhance Selectivity and Therapeutic Efficacy in Photodynamic Therapy. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010065

Chicago/Turabian StylePłaskonka, Dominik M., Dominik Barczyk, Paweł Repetowski, Marta Warszyńska, and Janusz M. Dąbrowski. 2026. "Biomolecule–Photosensitizer Conjugates: A Strategy to Enhance Selectivity and Therapeutic Efficacy in Photodynamic Therapy" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010065

APA StylePłaskonka, D. M., Barczyk, D., Repetowski, P., Warszyńska, M., & Dąbrowski, J. M. (2026). Biomolecule–Photosensitizer Conjugates: A Strategy to Enhance Selectivity and Therapeutic Efficacy in Photodynamic Therapy. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010065