In Silico Investigation of Amidine-Based BACE-1 Inhibitors Against Alzheimer’s Disease: SAR, Pharmacokinetics, Molecular Docking and Dynamic Simulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

2.1. Rational Behind Dataset Collection of BACE-1 Inhibitors

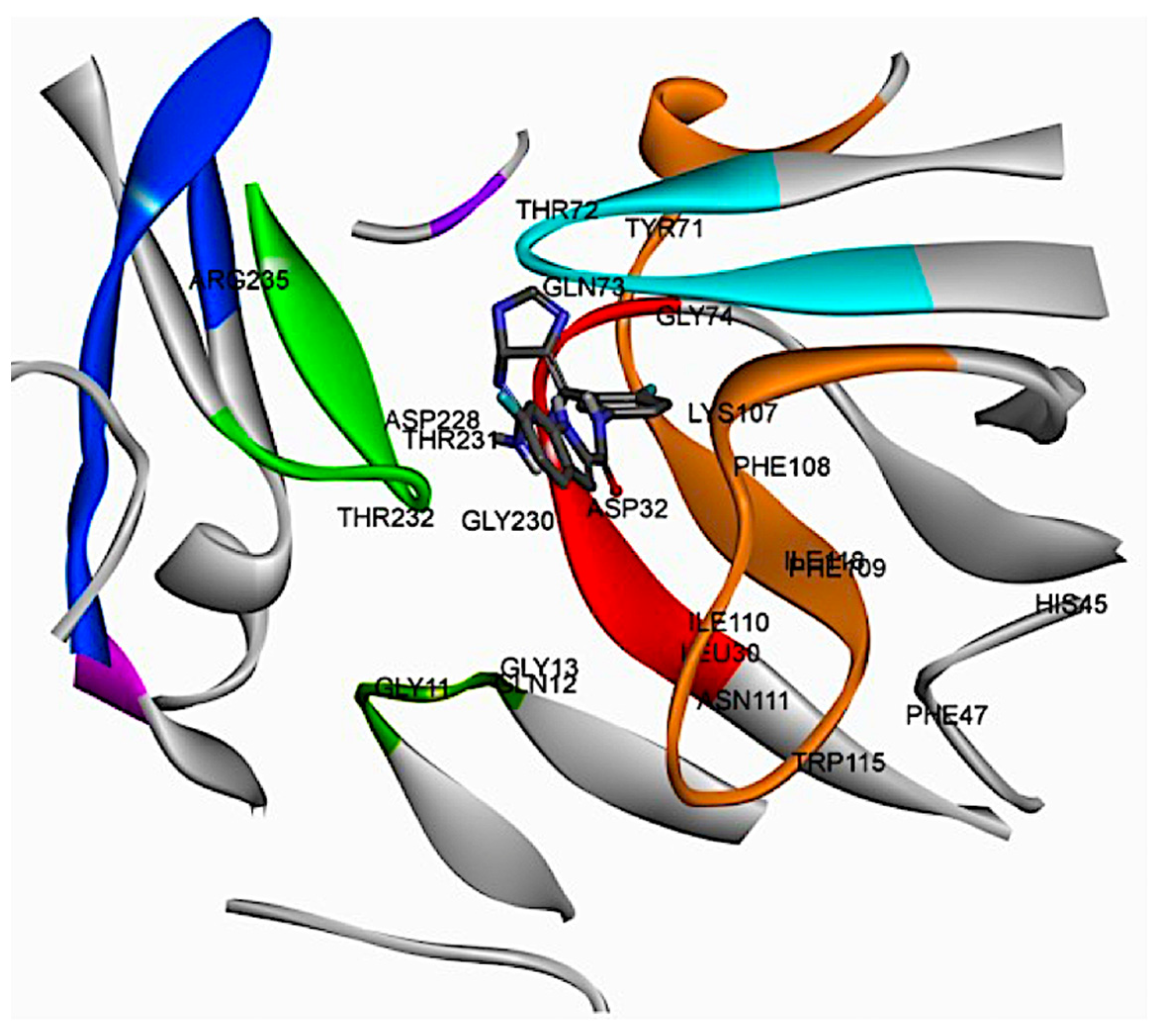

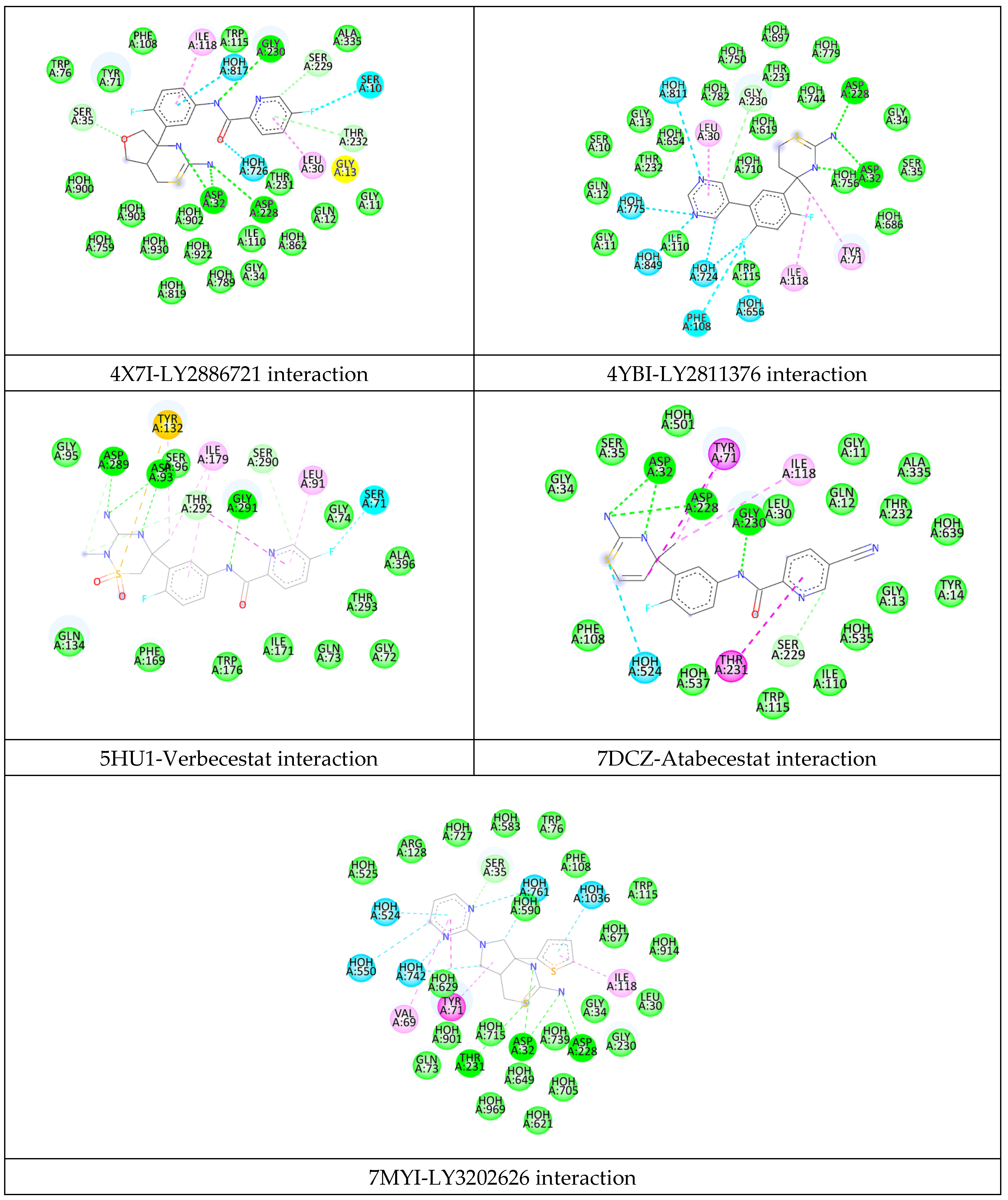

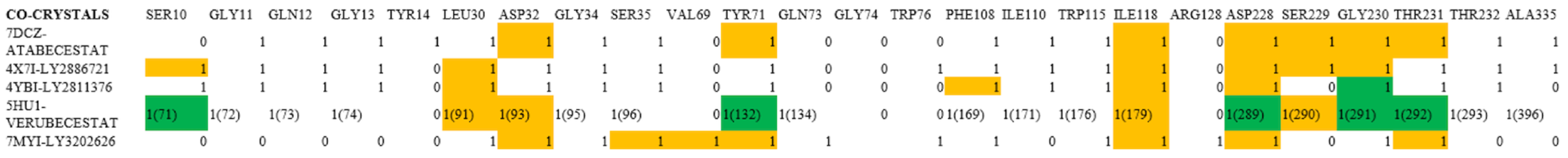

2.2. Analysis of the Binding Pocket of BACE-1 Through Co-Crystal (PDB) Structures and Molecular Docking Generated Docked Structures

2.3. Comparison of Binding of Pocket BACE-1 and BACE-2 for Designing of Selective Inhibitors

2.4. SAR and Rationale Design of BACE-1 Selective Inhibitor

2.5. In Silico Study of Designed Molecules

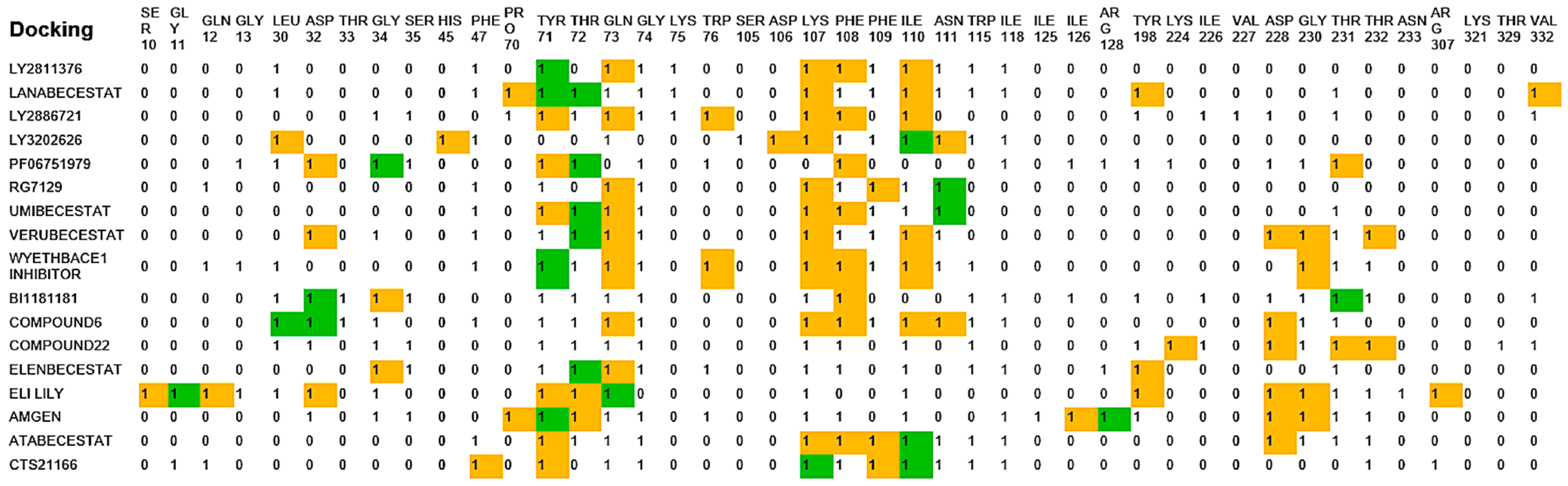

2.6. Molecular Docking

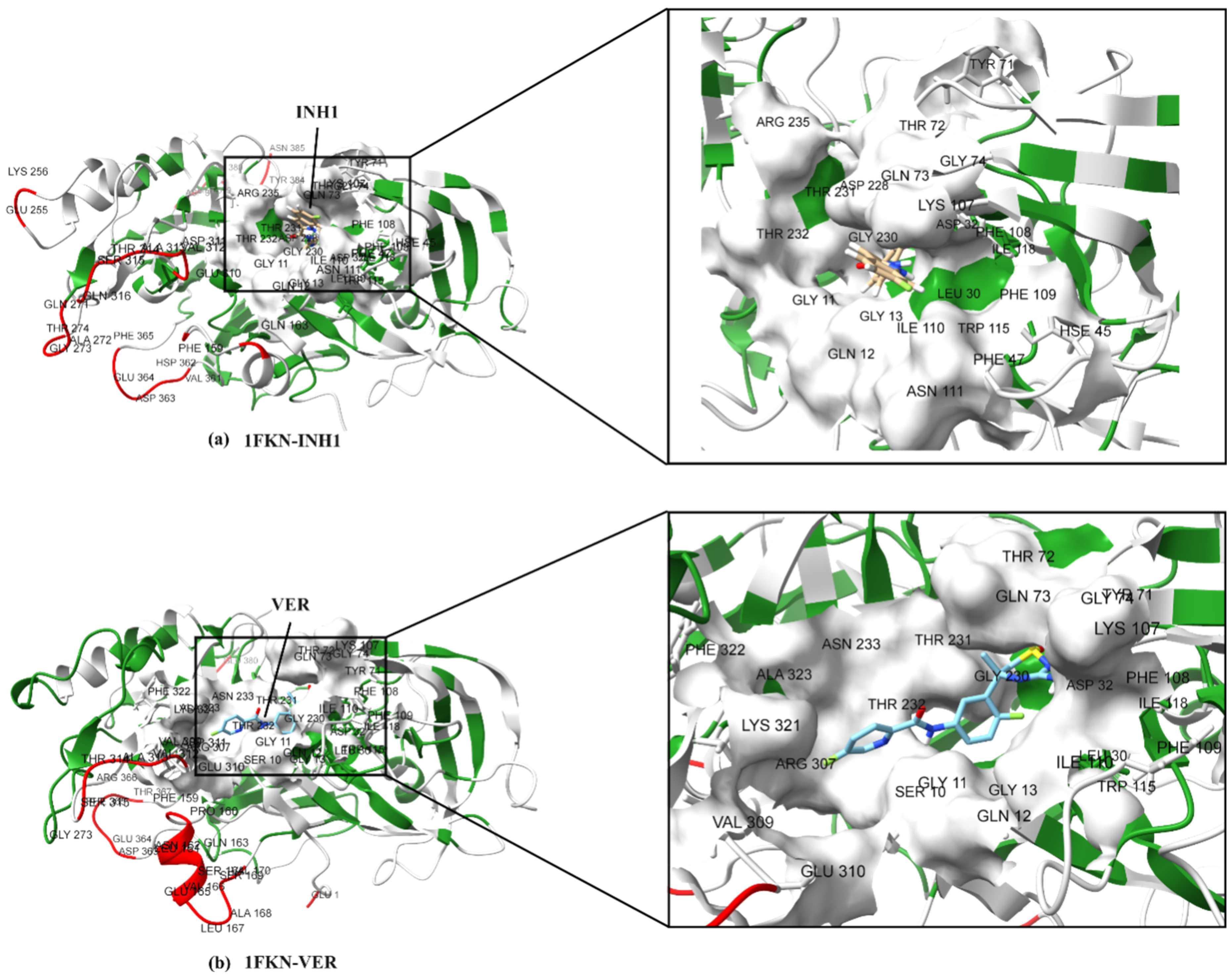

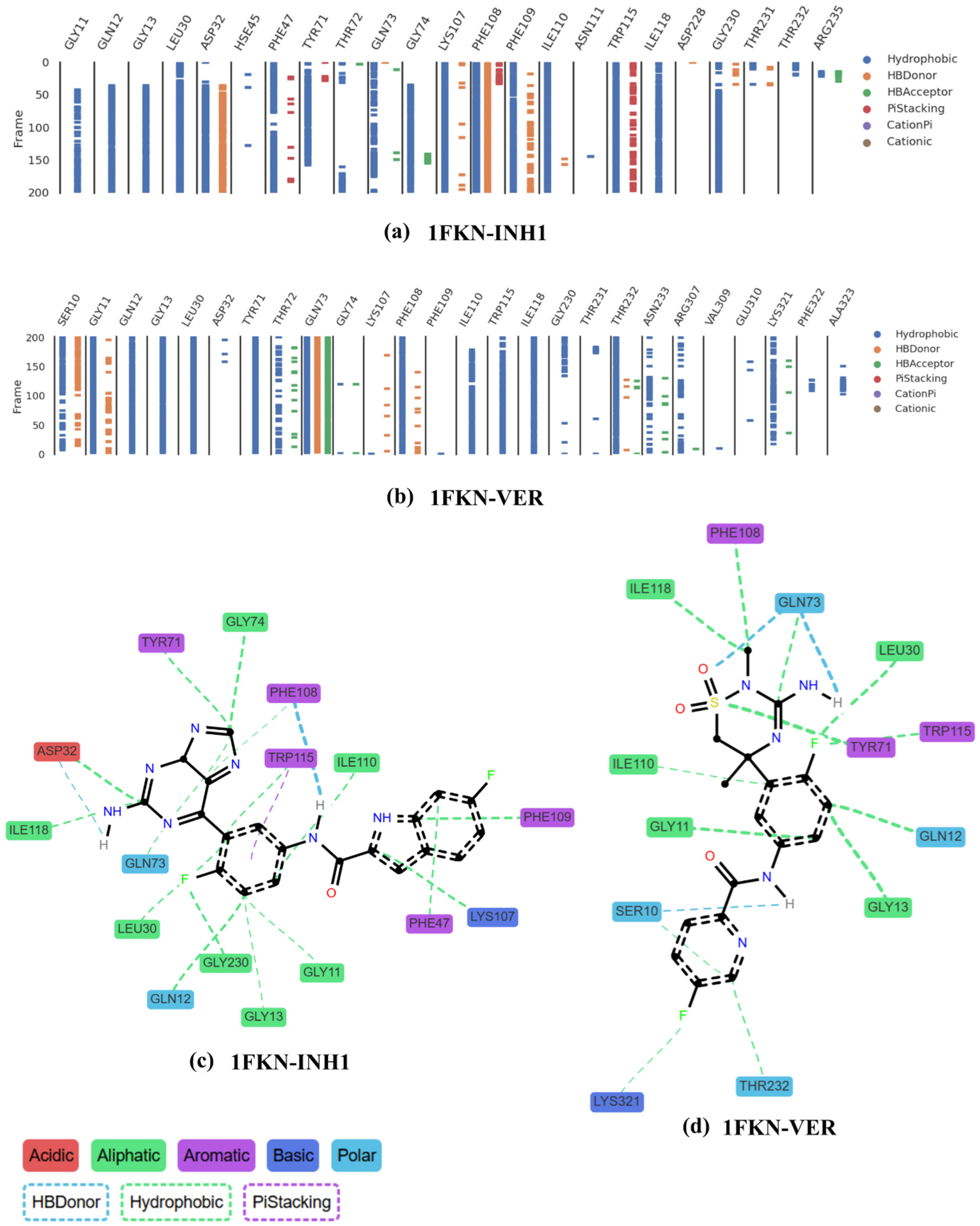

2.7. Molecular Dynamic Studies

2.7.1. Global Flexibility Trends

2.7.2. Active Site Residue Dynamics

2.7.3. Functional Implications of Flexibility Differences

2.7.4. Insights from Inhibitors Interaction Within the Pocket

3. Material and Method

3.1. Dataset Collection

3.2. Validation of the Binding Pocket Through Co-Crystal Analysis and Molecular Docking

3.3. SAR Study and Design of New BACE-1 Inhibitors

3.4. In Silico Study of Designed Molecules Using SwissADME Web Tool

3.5. Molecular Docking Experiment

3.6. Molecular Dynamic Simulations

3.7. ProLIF’s Interaction Fingerprint, Hydrogen Bonds, and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, R.; Vassar, R. Targeting the β secretase BACE1 for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, E.A.; Vassar, R. BACE Inhibitor Clinical Trials for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2024, 101, S41–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDade, E.; Voytyuk, I.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Carrillo, M.C.; De Strooper, B.; Haass, C.; Reiman, E.M.; Sperling, R.; Tariot, P.N.; et al. The case for low-level BACE1 inhibition for the prevention of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Osswald, H.L. BACE1 (β-secretase) inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6765–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.F.; Kost, J.; Tariot, P.N.; Aisen, P.S.; Cummings, J.L.; Vellas, B.; Sur, C.; Mukai, Y.; Voss, T.; Furtek, C.; et al. Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.F.; Kost, J.; Voss, T.; Mukai, Y.; Aisen, P.S.; Cummings, J.L.; Tariot, P.N.; Vellas, B.; van Dyck, C.H.; Boada, M.; et al. Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1408–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.C.; Willis, B.A.; Lowe, S.L.; Dean, R.A.; Monk, S.A.; Cocke, P.J.; Audia, J.E.; Boggs, L.N.; Borders, A.R.; Brier, R.A.; et al. The potent BACE1 inhibitor LY2886721 elicits robust central Aβ pharmacodynamic responses in mice, dogs, and humans. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, M.J.; Greenblatt, H.; Chen, W.; Paz, A.; Dym, O.; Peleg, Y.; Chen, T.; Shen, X.; He, J.; et al. Flexibility of the flap in the active site of BACE1 as revealed by crystal structures and molecular dynamics simulations. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012, 68 Pt 1, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsafian, H.; Mat Ripen, A.; Merican, A.F.; Bin Mohamad, S. Amino acid sequence and structural comparison of BACE1 and BACE2 using evolutionary trace method. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 482463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, S.L.; Vassar, R. The role of amyloid precursor protein processing by BACE1, the beta-secretase, in Alzheimer disease pathophysiology. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 29621–29625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, F.J.R.; Kusakabe, K.I.; Alexander, R.; Austin, N.; Borghys, H.; De Cleyn, M.; Dhuyvetter, D.; Gijsen, H.J.M.; Hrupka, B.; Jacobs, T.; et al. JNJ-67569762, A 2-Aminotetrahydropyridine-Based Selective BACE1 Inhibitor Targeting the S3 Pocket: From Discovery to Clinical Candidate. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 14175–14191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Paramanick, D. β-Secretase as a Primary Drug Target of Alzheimer Disease: Function, Structure, and Inhibition. In Deciphering Drug Targets for Alzheimer’s Disease; Kumar, D., Patil, V.M., Wu, D., Thorat, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, K.; Matsuoka, E.; Asada, N.; Tadano, G.; Yamamoto, T.; Nakahara, K.; Fuchino, K.; Ito, H.; Kanegawa, N.; Moechars, D.; et al. Structure-Based Design of Selective β-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein Cleaving Enzyme 1 (BACE1) Inhibitors: Targeting the Flap to Gain Selectivity over BACE2. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5080–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, K.; Yoshida, S.; Tadano, G.; Asada, N.; Fuchino, K.; Suzuki, S.; Matsuoka, E.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Ando, S.; et al. Structure-Based Approaches to Improving Selectivity through Utilizing Explicit Water Molecules: Discovery of Selective β-Secretase (BACE1) Inhibitors over BACE2. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 3075–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, T.; Matsuoka, E.; Asada, N.; Yamamoto, S.; Kanegawa, N.; Ito, M.; Ito, H.; Moechars, D.; Rombouts, F.J.R.; Gijsen, H.J.M.; et al. Discovery of Extremely Selective Fused Pyridine-Derived β-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein-Cleaving Enzyme (BACE1) Inhibitors with High In Vivo Efficacy through 10s Loop Interactions. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 14165–14174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Bottegoni, G.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Cavalli, A. BACE-1 Inhibitors: From Recent Single-Target Molecules to Multitarget Compounds for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.C.; Dean, R.A.; Lowe, S.L.; Martenyi, F.; Sheehan, S.M.; Boggs, L.N.; Monk, S.A.; Mathes, B.M.; Mergott, D.J.; Watson, B.M.; et al. Robust central reduction of amyloid-β in humans with an orally available, non-peptidic β-secretase inhibitor. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 16507–16516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.D.; Li, S.W.; Brunskill, A.P.; Chen, X.; Cox, K.; Cumming, J.N.; Forman, M.; Gilbert, E.J.; Hodgson, R.A.; Hyde, L.A.; et al. Discovery of the 3-Imino-1,2,4-thiadiazinane 1,1-Dioxide Derivative Verubecestat (MK-8931)-A β-Site Amyloid Precursor Protein Cleaving Enzyme 1 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10435–10450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koriyama, Y.; Hori, A.; Ito, H.; Yonezawa, S.; Baba, Y.; Tanimoto, N.; Ueno, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Asada, N.; et al. Discovery of Atabecestat (JNJ-54861911): A Thiazine-Based β-Amyloid Precursor Protein Cleaving Enzyme 1 Inhibitor Advanced to the Phase 2b/3 EARLY Clinical Trial. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 1873–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinzie, D.L.; Winneroski, L.L.; Green, S.J.; Hembre, E.J.; Erickson, J.A.; Willis, B.A.; Monk, S.A.; Aluise, C.D.; Baker, T.K.; Lopez, J.E.; et al. Discovery and Early Clinical Development of LY3202626, a Low-Dose, CNS-Penetrant BACE Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 8076–8100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Autodock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexiblity. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 16, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar]

- The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 3.0; Schrödinger, LLC.: New York, NY, USA, 2024.

- Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), version 2008; Chemical Computing Group ULC: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2008.

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, L.; Koelsch, G.; Lin, X.; Wu, S.; Terzyan, S.; Ghosh, A.K.; Zhang, X.C.; Tang, J. Structure of the protease domain of memapsin 2 (beta-secretase) complexed with inhibitor. Science 2000, 290, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Im, W. Automated builder and database of protein/membrane complexes for molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.C.; Myers, J.B.; Folta, T.; Shoja, V.; Heath, L.S.; Onufriev, A. H++: A server for estimating pKas and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W368–W371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaker, V.; Srivastava, P.N.; Debnath, U.; Srivastava, A.K.; Prabhakar, Y.S. MD simulations for rational design of high-affinity HDAC4 inhibitors—Analysis of non-bonding interaction energies for building new compounds. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 764, 110262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Jo, S.; Brooks, C.L., 3rd; Lee, H.S.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI ligand reader and modeler for CHARMM force field generation of small molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2017, 38, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, B.; Kutzner, C.; van der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for Highly Efficient, Load-Balanced, and Scalable Molecular Simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.C.; Fraaije, J.G.E.M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyna, G.J.; Hughes, A.; Tuckerman, M.E. Molecular dynamics algorithms for path integrals at constant pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 3275–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Dewaker, V.; Debnath, U.; Jana, K.; Rath, J.; Joardar, N.; Sinha Babu, S.P. In silico exploration and in vitro validation of the filarial thioredoxin reductase inhibitory activity of Scytonemin and its derivatives. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 43, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouysset, C.; Fiorucci, S. ProLIF: A library to encode molecular interactions as fingerprints. J. Cheminformatics 2021, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.R., 3rd; McGee, T.D., Jr.; Swails, J.M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A.E. MMPBSA.py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy Calculations (Single Trajectory Method). Available online: https://valdes-tresanco-ms.github.io/gmx_MMPBSA/dev/examples/Protein_ligand/ST/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

| BACE-1 Residue | BACE-2 Residue | Conservation Status | Reported/Possible Effects on Target Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASP32 | ASP48 | Conserved | Essential for proteolytic activity. |

| ASP228 | ASP241 | Conserved | Essential for proteolytic activity. |

| TYR71 | TYR87 | Conserved | Involved in substrate binding; contributes to flap dynamics. |

| ILE110 | LEU126 | Non-conserved | Ile side chain in BACE-1 has different spatial configuration, affecting the shape and hydrophobicity of the pocket. |

| ILE126 | LEU142 | Non-conserved | Alters the topology of the subsite, impacting substrate specificity. |

| TRP115 | TRP131 | Conserved | Contributes to the hydrophobic environment; differences may influence inhibitor design. |

| PHE108 | PHE124 | Conserved | Both residues are aromatic, but their spatial orientation may differ, affecting interactions with inhibitors. |

| ASN233 | LEU246 | Non-conserved | Asn is polar while Leu is nonpolar. Asn may influence hydrogen bonding in BACE-1 |

| PRO70 | LYS86 | Non-conserved | Pro70 in BACE-1 imparts rigidity to the flap region. In contrast, Lys86 in BACE-2 introduces a positive charge, altering local interactions. |

| Molecule (R1.R2) | 3.4 | 3.11 | 6.8 | 9.11 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 11.11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus Log P | 2.76 | 3.83 | 3.44 | 2.88 | 2.51 | 2.81 | 3.2 |

| GI absorption | High | High | High | High | High | High | High |

| Pgp substrate | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Lipinski #violations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ghose #violations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Veber #violations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Egan #violations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muegge #violations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Synthetic Accessibility | 4.66 | 4.8 | 4.81 | 4.25 | 4.04 | 4.06 | 3.91 |

| Pair Id | Donor Residue | Donor Atom | Acceptor Residue | Acceptor Atom | Avg. Distance (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | THR72 | OG1 | INH1386 | N26 | 0.91 |

| 2 | GLN73 | NE2 | INH1386 | O10 | 0.84 |

| 3 | GLY74 | N | INH1386 | N24 | 0.52 |

| 4 | ARG235 | NH1 | INH1386 | N25 | 1.06 |

| 5 | ARG235 | NH1 | INH1386 | N26 | 1.06 |

| 6 | ARG235 | NH2 | INH1386 | N26 | 1.02 |

| 7 | INH1386 | N8 | GLN73 | O | 0.72 |

| 8 | INH1386 | N8 | LYS107 | O | 0.41 |

| 9 | INH1386 | N8 | PHE108 | O | 0.30 |

| 10 | INH1386 | N17 | GLN73 | O | 0.80 |

| 11 | INH1386 | N17 | LYS107 | O | 0.34 |

| 12 | INH1386 | N17 | PHE108 | O | 0.32 |

| 13 | INH1386 | N17 | PHE109 | O | 0.35 |

| 14 | INH1386 | N17 | ILE110 | N | 0.43 |

| 15 | INH1386 | N29 | ASP32 | OD1 | 0.38 |

| 16 | INH1386 | N29 | ASP32 | OD2 | 0.39 |

| 17 | INH1386 | N29 | ASP228 | OD2 | 0.58 |

| 18 | INH1386 | N29 | GLY230 | O | 0.57 |

| 19 | INH1386 | N29 | THR231 | OG1 | 0.68 |

| Pair Id | Donor Residue | Donor Atom | Acceptor Residue | Acceptor Atom | Avg. Distance (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | THR72 | N | VER386 | O13 | 0.36 |

| 2 | THR72 | OG1 | VER386 | O13 | 0.44 |

| 3 | GLN73 | N | VER386 | O12 | 0.56 |

| 4 | GLN73 | N | VER386 | O13 | 0.33 |

| 5 | GLN73 | NE2 | VER386 | O21 | 0.8 |

| 6 | GLY74 | N | VER386 | O12 | 0.75 |

| 7 | THR232 | OG1 | VER386 | N19 | 0.52 |

| 8 | THR232 | OG1 | VER386 | N23 | 0.43 |

| 9 | ASN233 | ND2 | VER386 | N23 | 0.71 |

| 10 | VER386 | N18 | GLN73 | O | 0.31 |

| 11 | VER386 | N18 | LYS107 | O | 0.44 |

| 12 | VER386 | N18 | PHE108 | O | 0.38 |

| 13 | VER386 | N19 | SER10 | O | 0.38 |

| 14 | VER386 | N19 | GLY11 | O | 0.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gandhi, V.; Dewaker, V.; Agarwal, U.; Patil, V.M.; Park, S.T.; Kim, H.S.; Verma, S. In Silico Investigation of Amidine-Based BACE-1 Inhibitors Against Alzheimer’s Disease: SAR, Pharmacokinetics, Molecular Docking and Dynamic Simulations. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010005

Gandhi V, Dewaker V, Agarwal U, Patil VM, Park ST, Kim HS, Verma S. In Silico Investigation of Amidine-Based BACE-1 Inhibitors Against Alzheimer’s Disease: SAR, Pharmacokinetics, Molecular Docking and Dynamic Simulations. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleGandhi, Vaibhav, Varun Dewaker, Uma Agarwal, Vaishali M. Patil, Sung Taek Park, Hyeong Su Kim, and Saroj Verma. 2026. "In Silico Investigation of Amidine-Based BACE-1 Inhibitors Against Alzheimer’s Disease: SAR, Pharmacokinetics, Molecular Docking and Dynamic Simulations" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010005

APA StyleGandhi, V., Dewaker, V., Agarwal, U., Patil, V. M., Park, S. T., Kim, H. S., & Verma, S. (2026). In Silico Investigation of Amidine-Based BACE-1 Inhibitors Against Alzheimer’s Disease: SAR, Pharmacokinetics, Molecular Docking and Dynamic Simulations. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010005