CYP2C:TG Haplotype in Native Mexicans, Molecular Ancestry and Its Implications for CYP2C19 Genotype–Phenotype Correlation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. CYP2C19 Genotype and CYP2C Haplotype

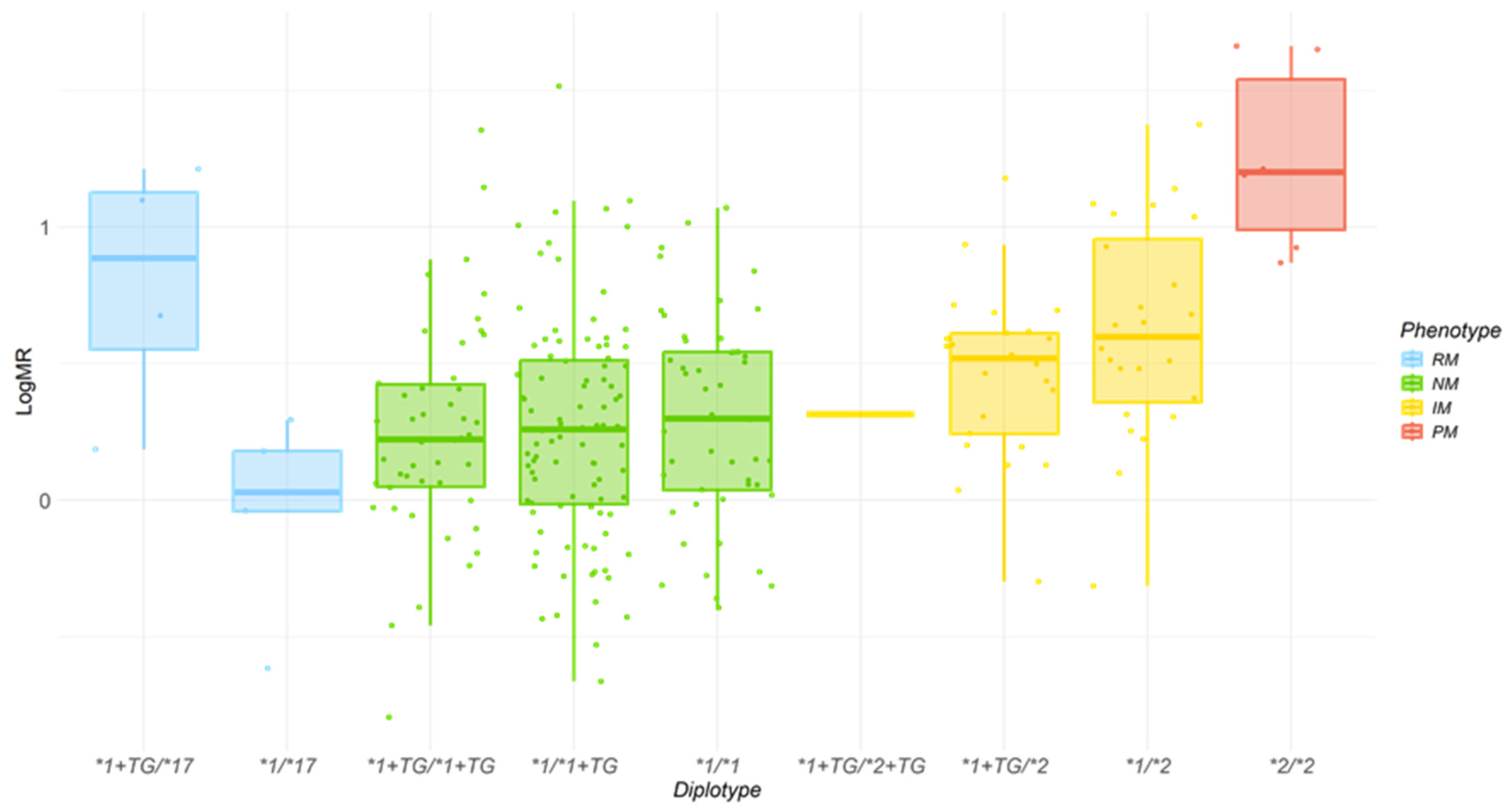

2.2. Effect of CYP2C19 Genotypes and CYP2C Haplotype on logMR

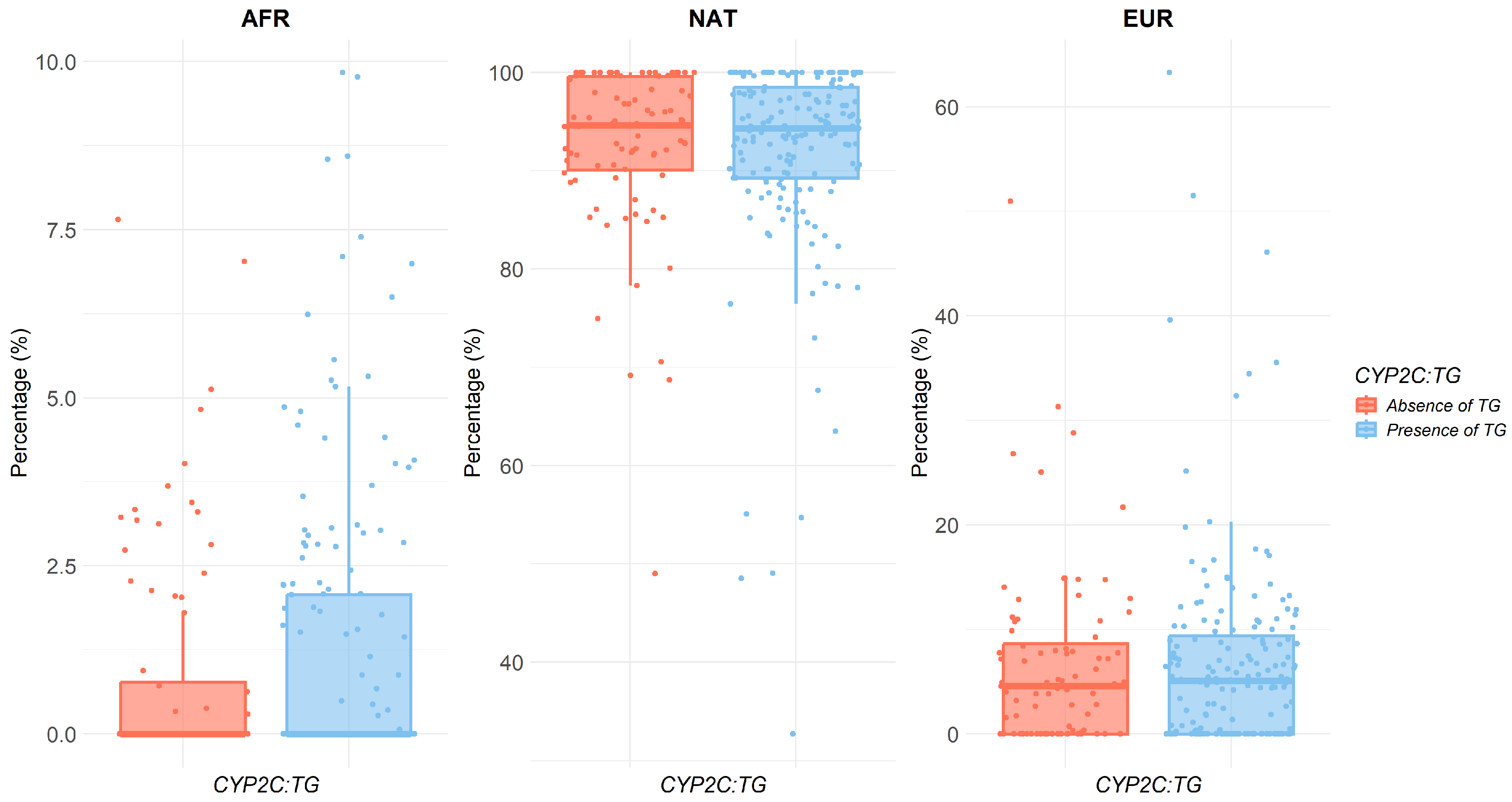

2.3. Relationship Between Ancestry and Metabolic Ratio

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. CYP2C19 Alleles and CYP2C Haplotype

4.3. Phenotyping Procedure

4.4. Ancestry

4.5. Statistical Analysis

4.5.1. Analysis of the Impact of the CYP2C:TG Haplotype on the logMR Levels

4.5.2. Analysis of the Relationship Between Ancestry and CYP2C Haplotypes

4.5.3. Inference of Individual Haplotypes and Diplotypes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Activity score |

| gIMs | Intermediate metabolizers |

| gNMs | Normal metabolizers |

| gPMs | Poor metabolizers |

| gRMs | Rapid metabolizers |

| gUMs | Ultrarapid metabolizers |

| logMR | Metabolic ratio logarithm |

| MR | Metabolic ratio |

Appendix A

RIBEF-IBEROFEN Consortium for the Study of Phenotype-Genotype Relationships and Ancestry in Native American Populations

- RIBEF/SIFF Red y Sociedad Iberoamericana de Farmacogenética y Farmacogenómica. Spain

- INUBE University Institute for Bio-Sanitary Research of Extremadura. Badajoz, Spain.

- Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Extremadura. Badajoz, Spain.

- Unit of Pharmacogenomics and Personalized Medicine. Clinical Pharmacology Service. Badajoz University Hospital, SES. Badajoz, Spain.

- Current address: Department of Analytical Chemistry and Food Technology. Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Castilla-La Mancha. Albacete, Spain.

- Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidade de Campinas. Campinas, Sao Paulo, Brasil.

- Department of Pathology, Genetic and Evolution, Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, Uberaba, Brasil.

- IPN Instituto Politécnico Nacional. CIIDIR Unidad Durango. Academia de Genómica. Durango, México.

- Colegio de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

- UNAN Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, León, Nicaragua.

- Facultad de Odontología, Universidad Americana, Managua, Nicaragua.

References

- Botton, M.R.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Del Tredici, A.L.; Sangkuhl, K.; Cavallari, L.H.; Agúndez, J.A.G.; Duconge, J.; Lee, M.T.M.; Woodahl, E.L.; Claudio-Campos, K.; et al. PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2C19. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PharmVar. Available online: https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP2C19 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- de Godoy Torso, N.; Rodrigues-Soares, F.; Altamirano, C.; Ramírez-Roa, R.; Sosa-Macías, M.; Galavíz-Hernández, C.; Terán, E.; Peñas-LLedó, E.; Dorado, P.; LLerena, A. CYP2C19 Genotype-Phenotype Correlation: Current Insights and Unanswered Questions. Drug Metab. Pers. Ther. 2024, 39, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.R.; Luzum, J.A.; Sangkuhl, K.; Gammal, R.S.; Sabatine, M.S.; Stein, C.M.; Kisor, D.F.; Limdi, N.A.; Lee, Y.M.; Scott, S.A.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2C19 Genotype and Clopidogrel Therapy: 2022 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 112, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousman, C.A.; Stevenson, J.M.; Ramsey, L.B.; Sangkuhl, K.; Hicks, J.K.; Strawn, J.R.; Singh, A.B.; Ruaño, G.; Mueller, D.J.; Tsermpini, E.E.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2B6, SLC6A4, and HTR2A Genotypes and Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 114, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, J.J.; Thomas, C.D.; Barbarino, J.; Desta, Z.; Van Driest, S.L.; El Rouby, N.; Johnson, J.A.; Cavallari, L.H.; Shakhnovich, V.; Thacker, D.L.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2C19 and Proton Pump Inhibitor Dosing. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CYP2C18. Available online: https://www.clinpgx.org/gene/PA127/pathway (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Bråten, L.S.; Haslemo, T.; Jukic, M.M.; Ivanov, M.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Molden, E.; Kringen, M.K. A Novel CYP2C-Haplotype Associated With Ultrarapid Metabolism of Escitalopram. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 110, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bråten, L.S.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Jukic, M.M.; Molden, E.; Kringen, M.K. Impact of the Novel CYP2C:TG Haplotype and CYP2B6 Variants on Sertraline Exposure in a Large Patient Population. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2022, 15, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganoci, L.; Palić, J.; Trkulja, V.; Starčević, K.; Šimičević, L.; Božina, N.; Lovrić-Benčić, M.; Poljaković, Z.; Božina, T. Is CYP2C Haplotype Relevant for Efficacy and Bleeding Risk in Clopidogrel-Treated Patients? Genes 2024, 15, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaur, P.; Leeder, J.S.; Abad-Santos, F.; Gaedigk, A. Response to “What Is the Current Clinical Impact of the CYP2C:TG Haplotype?”. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 115, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, V.C.; Pretti, M.A.M.; Tsuneto, L.T.; Petzl-Erler, M.L.; Suarez-Kurtz, G. Distribution of a Novel CYP2C Haplotype in Native American Populations. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1114742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ayala, A.; de la Cruz, C.G.; Dorado, P.; Rodrigues-Soares, F.; Castillo-Nájera, F.; LLerena, A.; Molina-Guarneros, J. Molecular Ancestry Across Allelic Variants of SLC22A1, SLC22A2, SLC22A3, ABCB1, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 in Mexican-Mestizo DMT2 Patients. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Andrés, F.; Terán, S.; Bovera, M.; Fariñas, H.; Terán, E.; LLerena, A. Multiplex Phenotyping for Systems Medicine: A One-Point Optimized Practical Sampling Strategy for Simultaneous Estimation of CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 Activities Using a Cocktail Approach. OMICS A J. Integr. Biol. 2016, 20, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrés, F.; Sosa-Macías, M.; Ramos, B.P.L.; Naranjo, M.E.G.; LLerena, A. CYP450 Genotype/Phenotype Concordance in Mexican Amerindian Indigenous Populations-Where to from Here for Global Precision Medicine? OMICS A J. Integr. Biol. 2017, 21, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyler, K.E.; Gaedigk, A.; Abdel-Rahman, S.; Staggs, V.S.; Pearce, R.E.; Toren, P.; Leeder, J.S.; Shakhnovich, V. Influence of Novel CYP2C-Haplotype on Proton Pump Inhibitor Pharmacokinetics in Children. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubiaur, P.; Gaedigk, A. CYP2C18: The Orphan in the CYP2C Family. Pharmacogenomics 2022, 23, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Kurtz, G. Pharmacogenetic Testing in Admixed Populations: Frequency of the Association for Molecular Pathology Pharmacogenomics Working Group Tier 1 Variant Alleles in Brazilians. J. Mol. Diagn. 2025, 27, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, P.S.; Maggo, S.D.S.; Kennedy, M.A.; Barclay, M.L.; Miller, A.L.; Lehnert, K.; Curtis, M.A.; Faull, R.L.M.; Parker, R.; Chin, P.K.L. Omeprazole Treatment Failure in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Genetic Variation at the CYP2C Locus. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 869160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaur, P.; Soria-Chacartegui, P.; Boone, E.C.; Prasad, B.; Dinh, J.; Wang, W.Y.; Zugbi, S.; Rodríguez-Lopez, A.; González-Iglesias, E.; Leeder, J.S.; et al. Impact of CYP2C:TG Haplotype on CYP2C19 Substrates Clearance In Vivo, Protein Content, and In Vitro Activity. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 114, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Miner, J.O.; Veronese, M.E.; Tassaneeyakul, W.; Tassaneeyakul, W.; Meyer, U.A.; Birkett, D.J. Identification of Human Liver Cytochrome P450 Isoforms Mediating Omeprazole Metabolism. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993, 36, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Han, Q.; Zhou, X.; Cui, T.; Liu, S.; Zhao, T.; Wu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Elucidation of the Compatibility Mechanism of Yuanhuzhitong Prescription in View of CYP-Mediated Herbal Inter-Component Interactions. Fitoterapia 2025, 187, 106934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veringa, A.; ter Avest, M.; Span, L.F.R.; van den Heuvel, E.R.; Touw, D.J.; Zijlstra, J.G.; Kosterink, J.G.W.; van der Werf, T.S.; Alffenaar, J.W.C. Voriconazole Metabolism Is Influenced by Severe Inflammation: A Prospective Study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi, A.; Murakami, S.; Akizuki, S.; Mochizuki, J.; Echizen, H.; Takagi, I. In Vivo Metabolic Activity of CYP2C19 and CYP3A in Relation to CYP2C19 Genetic Polymorphism in Chronic Liver Disease. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 45, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, M. Global Distribution of CYP2C19 Risk Phenotypes Affecting Safety and Effectiveness of Medications. Pharmacogenom. J. 2021, 21, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, J.K.; Sangkuhl, K.; Swen, J.J.; Ellingrod, V.L.; Müller, D.J.; Shimoda, K.; Bishop, J.R.; Kharasch, E.D.; Skaar, T.C.; Gaedigk, A.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline (CPIC) for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotypes and Dosing of Tricyclic Antidepressants: 2016 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 102, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukic, M.M.; Opel, N.; Ström, J.; Carrillo-Roa, T.; Miksys, S.; Novalen, M.; Renblom, A.; Sim, S.C.; Peñas-Lledó, E.M.; Courtet, P.; et al. Elevated CYP2C19 Expression Is Associated with Depressive Symptoms and Hippocampal Homeostasis Impairment. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñas-Lledó, E.M.; Guillaume, S.; de Andrés, F.; Cortés-Martínez, A.; Dubois, J.; Kahn, J.P.; Leboyer, M.; Olié, E.; LLerena, A.; Courtet, P. A One-Year Follow-up Study of Treatment-Compliant Suicide Attempt Survivors: Relationship of CYP2D6-CYP2C19 and Polypharmacy with Suicide Reattempts. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñas-LLedó, E.; Terán, E.; Sosa-Macías, M.; Galaviz-Hernández, C.; Gil, J.P.; Nair, S.; Diwakar, S.; Hernández, I.; Lara-Riegos, J.; Ramírez-Roa, R.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Clinical Pharmacogenetic Research Studies in Resource-Limited Settings: Conclusions From the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences–Ibero-American Network of Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Meeting. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 1595–1610.e5. [Google Scholar]

- De Andrés, F.; Sosa-Macías, M.; Llerena, A. A Rapid and Simple LC-MS/MS Method for the Simultaneous Evaluation of CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 Hydroxylation Capacity. Bioanalysis 2014, 6, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrés, F.; Terán, S.; Hernández, F.; Terán, E.; Llerena, A. To Genotype or Phenotype for Personalized Medicine? CYP450 Drug Metabolizing Enzyme Genotype-Phenotype Concordance and Discordance in the Ecuadorian Population. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2016, 20, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrés, F.; Altamirano-Tinoco, C.; Ramírez-Roa, R.; Montes-Mondragón, C.F.; Dorado, P.; Peñas-Lledó, E.M.; LLerena, A. Relationships between CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 Metabolic Phenotypes and Genotypes in a Nicaraguan Mestizo Population. Pharmacogenom. J. 2021, 21, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Soares, F.; Peñas-Lledó, E.M.; Tarazona-Santos, E.; Sosa-Macías, M.; Terán, E.; López-López, M.; Rodeiro, I.; Moya, G.E.; Calzadilla, L.R.; Ramírez-Roa, R.; et al. Genomic Ancestry, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 Among Latin Americans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 107, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.R.; Altshuler, D.M.; Durbin, R.M.; Bentley, D.R.; Chakravarti, A.; Clark, A.G.; Donnelly, P.; Eichler, E.E.; Flicek, P.; et al. A Global Reference for Human Genetic Variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.H.; Novembre, J.; Lange, K. Fast Model-Based Estimation of Ancestry in Unrelated Individuals. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grömping, U. Relative Importance for Linear Regression in R: The Package Relaimpo. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 17, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnwell, J.P.; Schaid, D.J. Title Statistical Analysis of Haplotypes with Traits and Covariates When Linkage Phase Is Ambiguous. 2016. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/haplo.stats/index.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

| CYP2C Haplotypes | CYP2C19 Alleles (n, %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| *1 | *17 | *2 | |

| CG | 113 (22.07) | 9 (1.76) | 61 (11.91) |

| TG | 218 (42.58) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.19) |

| TA | 110 (21.48) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| CYP2C Diplotypes | Phenotypes | Subjetcs, n, % | Sex | Age, Years, Mean (sd) | LogMR, Mean (sd) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men % | Women % | |||||

| TG haplotypes | ||||||

| *1+TG/*17 | gRM | 4 (1.6) | 50 | 50 | 55 (26.9) | 0.79 (0.47) |

| *1+TG/*1+TG | gNM | 46 (17.9) | 30.4 | 69.6 | 41.5 (17.7) | 0.25 (0.40) |

| *1/*1+TG | gNM | 96 (37.7) | 20.2 | 69.8 | 38.7 (15.2) | 0.26 (0.40) |

| *1+TG/*2+TG | gIM | 1 (0.4) | 100 | 0 | ||

| *1+TG/*2 | gIM | 25 (9.7) | 40 | 60 | 34.6 (14.9) | 0.46 (0.30) |

| CG or TA haplotypes | ||||||

| *1/*17 | gRM | 5 (1.9) | 80 | 20 | 42.8 (1.48) | −0.03 (0.35) |

| *1/*1 | gNM | 49 (19.1) | 18.4 | 81.6 | 38.6 (14.9) | 0.3 (0.38) |

| *1/*2 | gIM | 24 (9.3) | 38 | 62 | 43.9 (16.0) | 0.62 (0.39) |

| *2/*2 | gPM | 6 (2.3) | 16.7 | 83.3 | 45.5 (15.1) | 1.25 (0.34) |

| CYP2C Haplotypes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | TA | CG | |||||||

| Ancestry | Mean (sd) | p-Value | Mean (sd) | p-Value | Mean (sd) | p-Value | |||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||

| AFR | 0.87 (1.67) | 1.22 (2.15) | 0.35 | 1.33 (2.16) | 0.74 (1.67) | 0.005 | 0.92 (1.86) | 1.24 (2.10) | 0.13 |

| NAT | 92.5 (8.67) | 91.9 (10.1) | 0.80 | 91.7 (9.76) | 92.8 (9.53) | 0.06 | 92.3 (9.88) | 92.0 (9.55) | 0.32 |

| EUR | 6.62 (8.52) | 6.85 (9.46) | 0.98 | 6.98 (9.33) | 6.44 (8.89) | 0.36 | 6.78 (9.00) | 6.77 (9.28) | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

de la Cruz, C.G.; Torso, N.d.G.; Villatoro-García, J.A.; Mata-Martín, C.; Rodrigues-Soares, F.; Galaviz-Hernández, C.; Peñas-Lledó, E.; Sosa-Macías, M.; LLerena, A.; RIBEF-IBEROFEN Consortium. CYP2C:TG Haplotype in Native Mexicans, Molecular Ancestry and Its Implications for CYP2C19 Genotype–Phenotype Correlation. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010006

de la Cruz CG, Torso NdG, Villatoro-García JA, Mata-Martín C, Rodrigues-Soares F, Galaviz-Hernández C, Peñas-Lledó E, Sosa-Macías M, LLerena A, RIBEF-IBEROFEN Consortium. CYP2C:TG Haplotype in Native Mexicans, Molecular Ancestry and Its Implications for CYP2C19 Genotype–Phenotype Correlation. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010006

Chicago/Turabian Stylede la Cruz, Carla González, Nadine de Godoy Torso, Juan Antonio Villatoro-García, Carmen Mata-Martín, Fernanda Rodrigues-Soares, Carlos Galaviz-Hernández, Eva Peñas-Lledó, Martha Sosa-Macías, Adrián LLerena, and RIBEF-IBEROFEN Consortium. 2026. "CYP2C:TG Haplotype in Native Mexicans, Molecular Ancestry and Its Implications for CYP2C19 Genotype–Phenotype Correlation" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010006

APA Stylede la Cruz, C. G., Torso, N. d. G., Villatoro-García, J. A., Mata-Martín, C., Rodrigues-Soares, F., Galaviz-Hernández, C., Peñas-Lledó, E., Sosa-Macías, M., LLerena, A., & RIBEF-IBEROFEN Consortium. (2026). CYP2C:TG Haplotype in Native Mexicans, Molecular Ancestry and Its Implications for CYP2C19 Genotype–Phenotype Correlation. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010006