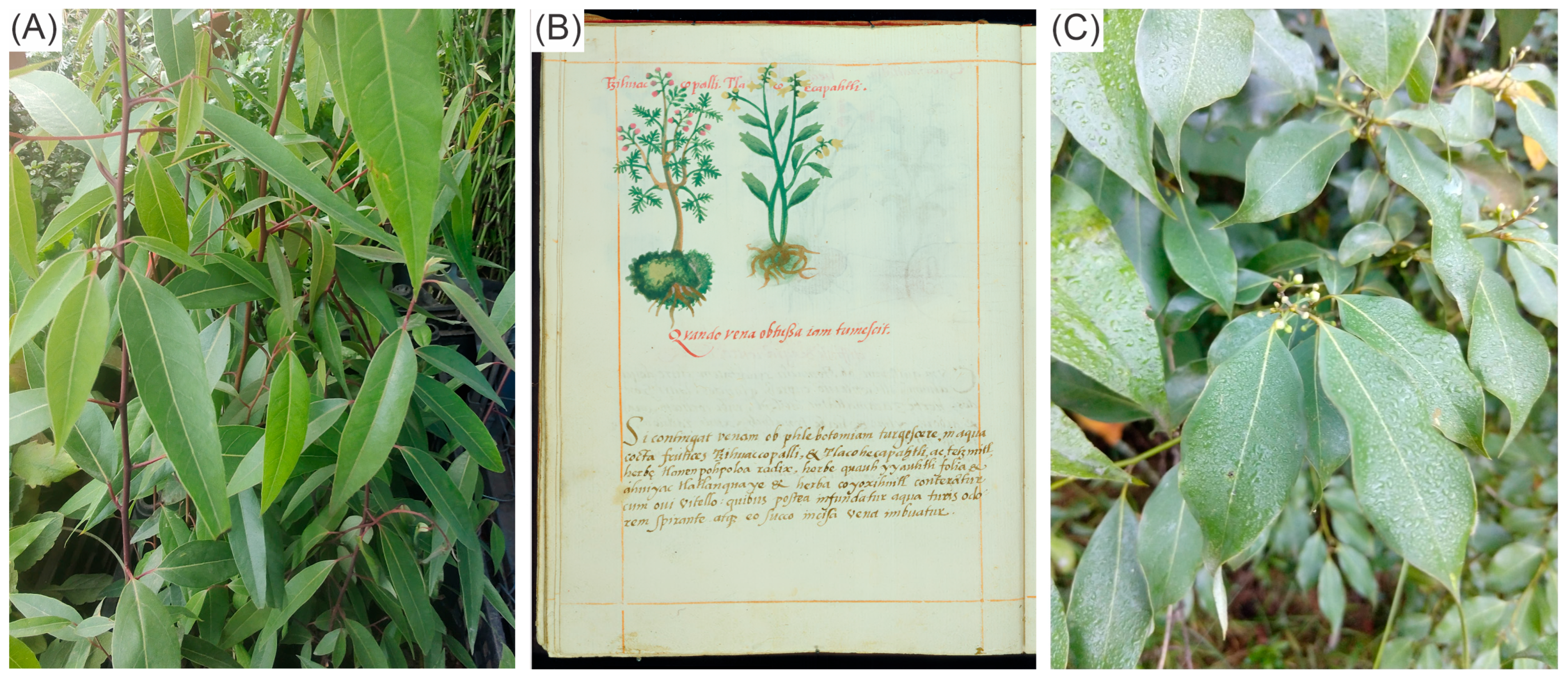

Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activity of Litsea glaucescens Kunth in Rodents, an Aztec Medicinal Plant Used in Pre-Columbian Times

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) of Extracts and Fractions

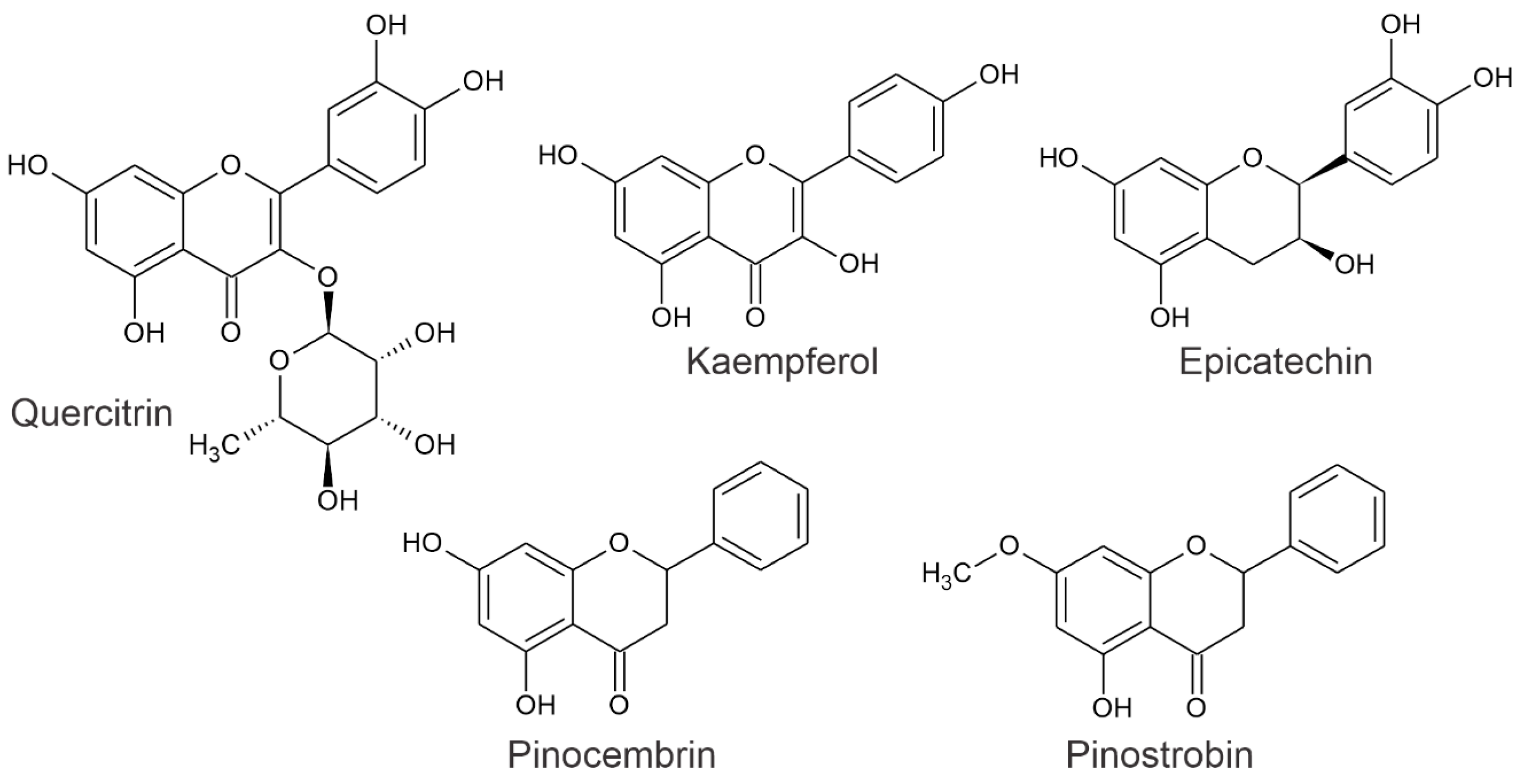

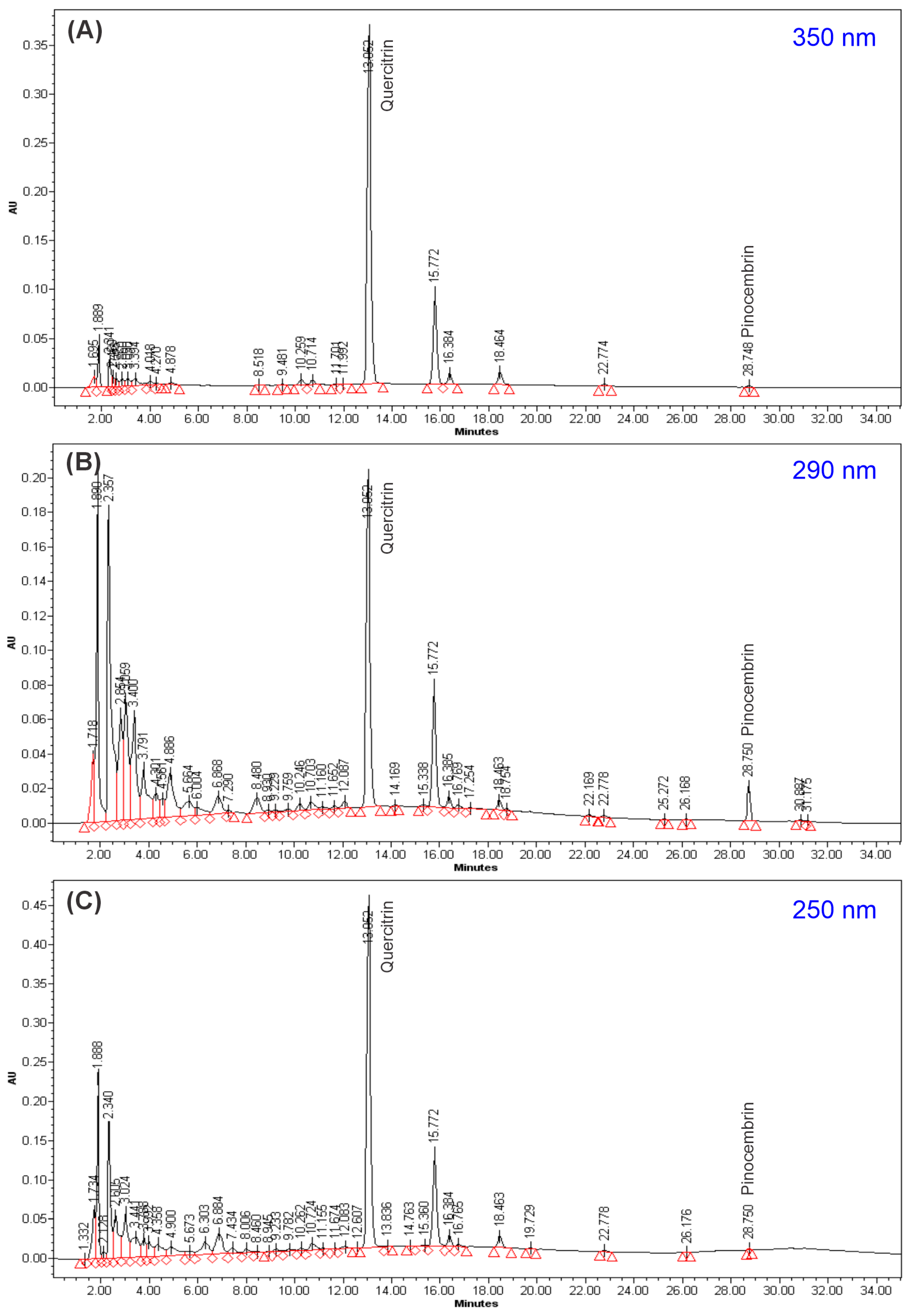

2.2. HPLC Analysis of GLAM

2.3. Analysis of GLAMF Fractionation, HPLC, and MS

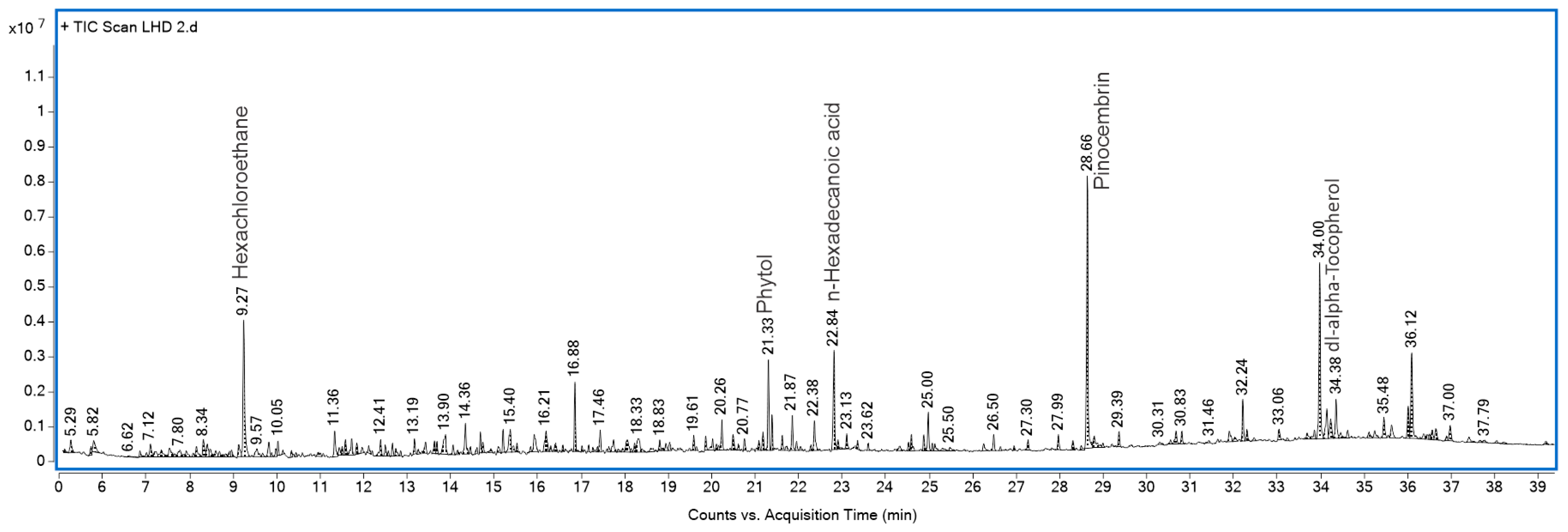

2.4. GLAHF Fractionation, GC-MS

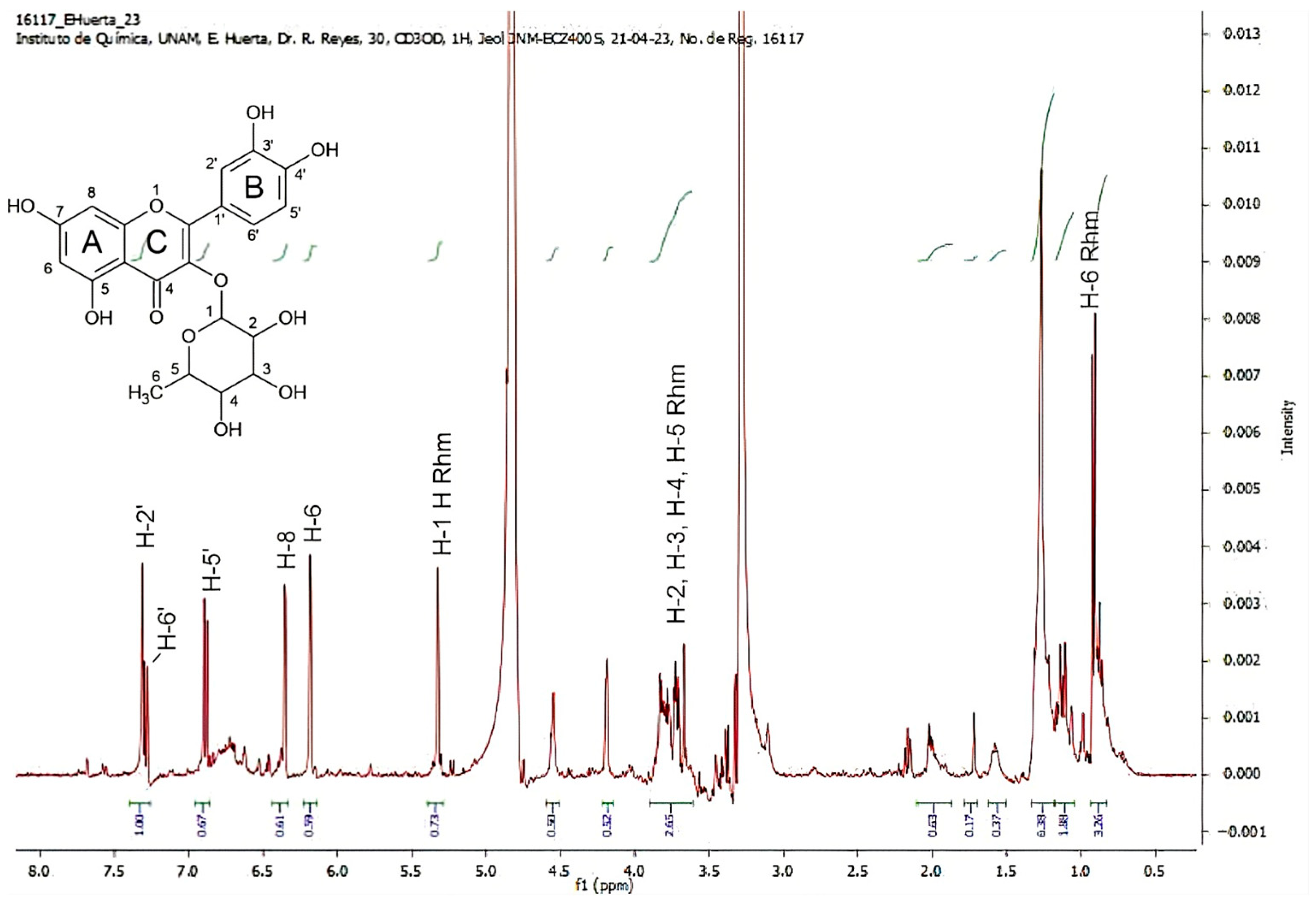

2.5. 1HRMN Analysis from GLAMF and GLAHF

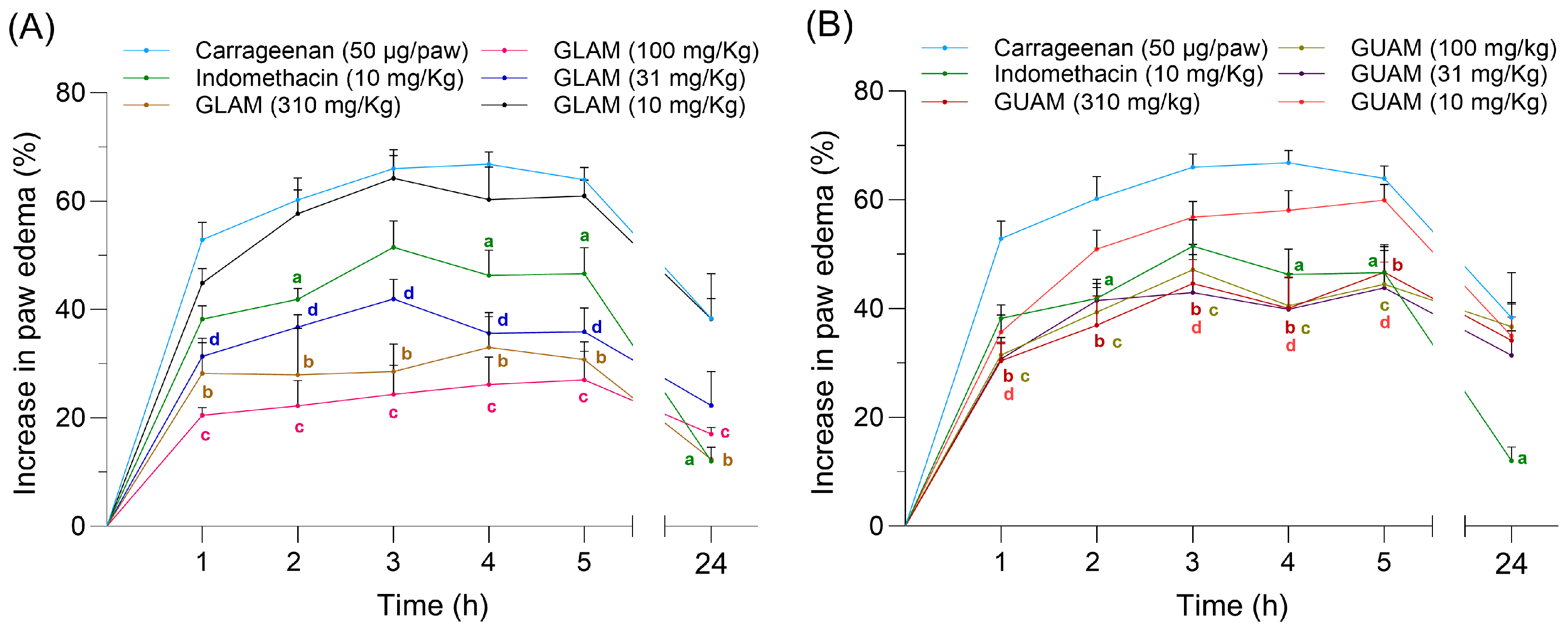

2.6. Effects of GLAM and GUAM on Carrageenan-Induced Paw Inflammation

2.7. Effects of GLAM and GUAM on TPA-Induced Mouse Ear Inflammation

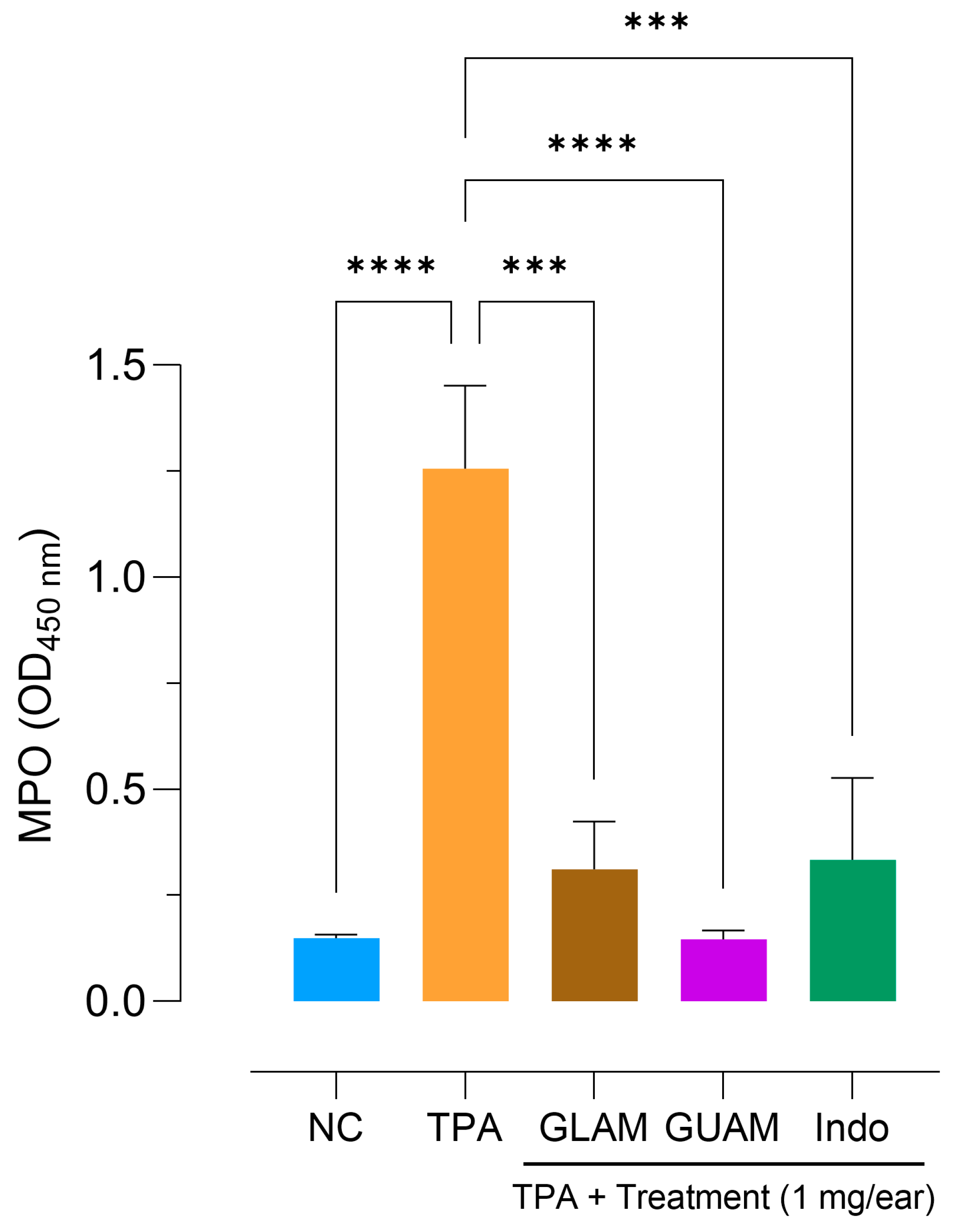

2.8. Inhibition of Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Activity

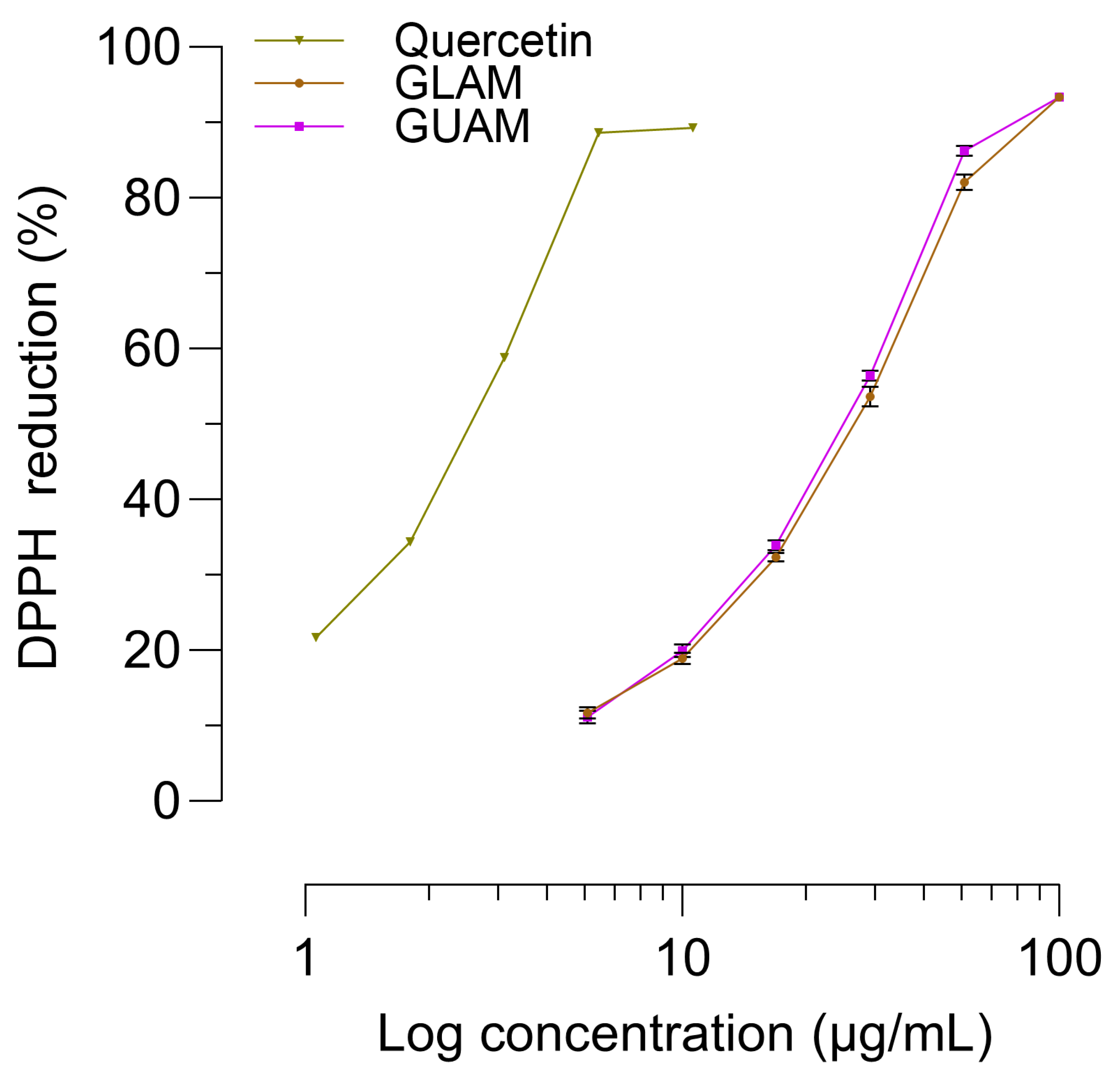

2.9. Analysis of DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

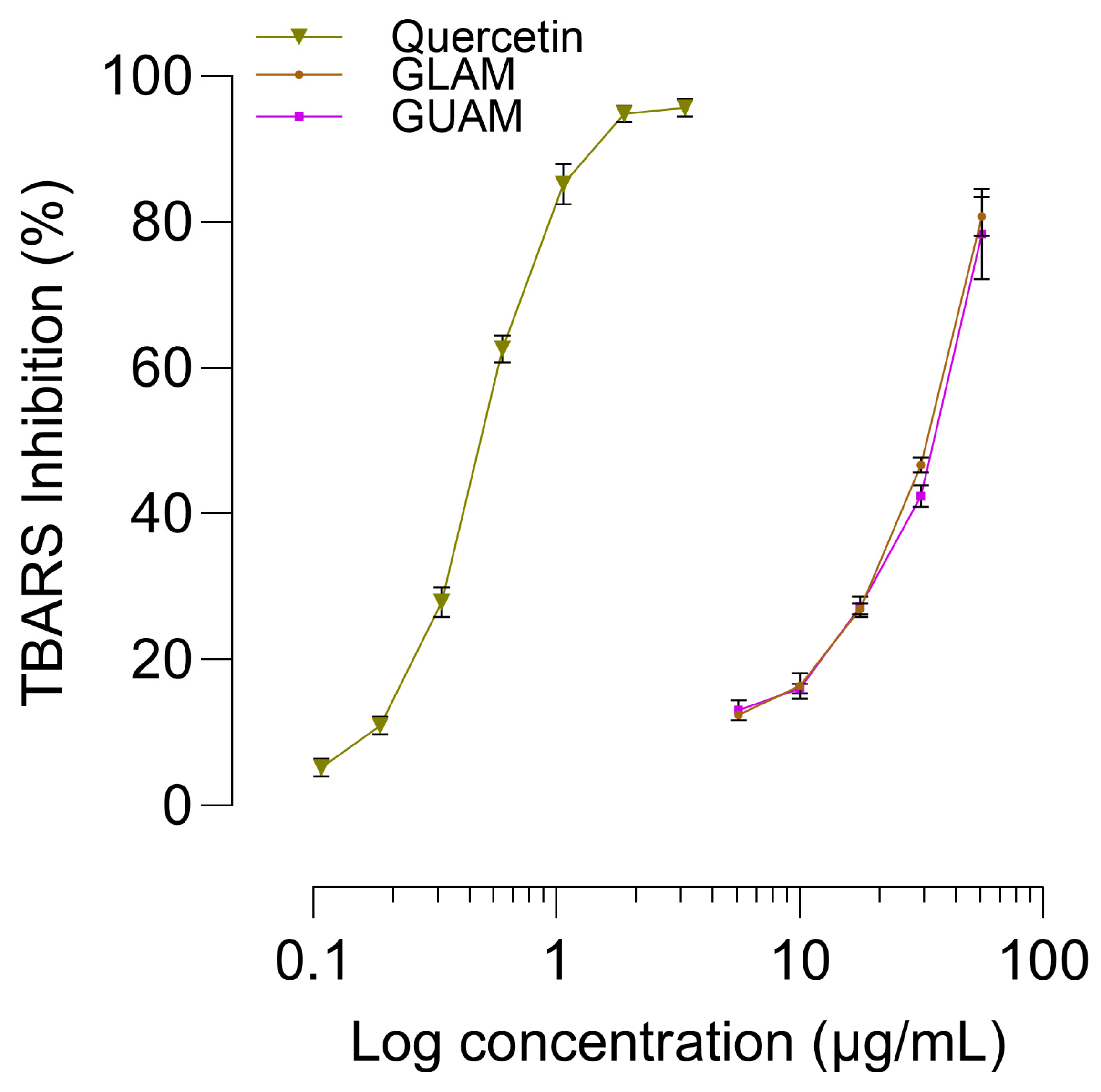

2.10. TBARS Assay Antioxidant Activity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Collection

4.2. Preparation of Plant Extracts

4.3. Chemicals and Solutions

4.4. Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC)

4.5. HPLC of GLAM

4.6. GLAMF Fractionation, HPLC, and MS

4.7. GLAHF Fractionation and GC-MS

4.8. 1NMR of GLAMF and GLAHF

4.9. Animal Care

4.10. Carrageenan-Induced Paw Inflammation

4.11. TPA-Induced Mouse Ear Inflammation

4.12. MPO Activity

4.13. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

4.14. TBARS Assay for Lipid Oxidation

4.15. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiménez-Pérez, N.d.C.; Lorea-Hernández, F.G. Identity and delimitation of the American species of Litsea Lam. (Lauraceae): A morphological approach. Plant Syst. Evol. 2009, 283, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010; Proteccion Ambiental-Especies Nativas De Mexico De Flora Y Fauna Silvestres-Categorias De Riesgo Y Especificaciones Para Su Inclusion, Exclusion O Cambio-Lista De Especies En Riesgo Prefacio. NORMA Oficial Mexicana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010.

- Tapia-Tapia, E.D.C.; Reyes-Chilpa, R.J. Mexican non-wood forest products: Economic aspects for sustainable development. Madera Bosques 2008, 14, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Why cook with bay leaves? Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 33, 100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pérez, N.d.C.; Lorea-Hernández, F.G.; Jankowski, C.K.; Reyes-Chilpa, R.J.E.B. Essential Oils in Mexican Bays (Litsea spp., Lauraceae): Taxonomic Assortment and Ethnobotanical Implications1. Econ. Bot. 2011, 65, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gutiérrez, B.; Pérez-Escandón, B.; Villavicencio-Nieto, M.J.R.d.F. Los Laureleros de Nopaltepec, Estado de México y el Uso de Litsea glaucenscens HEK (Lauraceae) de Tezoantla, Estado de Hidalgo, México. 1er Encuentro Hispano-Portugués de Etnobiología (EHPE 2010): Los Desafíos de la Etnobiología en España y Portugal. Sustain. Journey J. Tour. Dev. Compet. 2010, 10, 206–232. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes_Chilpa, R. On the first book of medicinal plants written in the American Continent: The libellus medicinalibus indorum herbis from Mexico, 1552: A review. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromáticas 2021, 20, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, M.; Badiano, J. Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis: Manuscrito Azteca de 1552 (Según Traducción Latina de Juan Badiano); Versión Española con Estudios y Comentarios por Diversos Autores; Mexican Social Security Institute: Mexico City, Mexico, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bye, R.; Linares, E. Códice De la Cruz-Badiano. Medicina Prehispánica. Rev. Arqueol. Mex. 2013, 50, 37–91. [Google Scholar]

- De Sahagún, B. Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España I; Linkgua Ediciones: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Magliabechiano, C. Libro de la Vida; Facsimilar, Ed.; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Motolinía, T. Historia de los Indios de la Nueva España; Linkgua Ediciones: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, F. Historia Natural de Nueva España; Universidad Nacional de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 1959; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Durán, D. Historia de las Indias de Nueva-España y Islas de Tierra Firme; JM Andrade y F. Escalante: Mexico City, Mexico, 1880; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- López Austin, A.J. Textos de Medicina Náhuatl; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas: Mexico City, Mexico, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Baldry, P. The Battle Against Bacteria: A Fresh Look; CUP Archive: Cambridge, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Marquina, S.; Antunez-Mojica, M.; González-Christen, J.; Romero-Estrada, A.; Ocampo-Bautista, F.; Nolasco-Quintana, N.Y.; Guerrero-Alonso, A.; Alvarez, L. Chemical Profiles and Nitric Oxide Inhibitory Activities of the Copal Resin and Its Volatile Fraction of Bursera bipinnata. Forests 2025, 16, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.F.d.; Nascimento, G.E.d.; Iacomini, M.; Cordeiro, L.M.C.; Cipriani, T.R. Chemical structure and anti-inflammatory effect of polysaccharides obtained from infusion of Sedum dendroideum leaves. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Miranda, D.Y.; Reyes-Chilpa, R.; Magos, G.A.; Avila Acevedo, J.G.; Guzman-Gutierrez, S.L.; Martinez-Ambriz, E.; Campos-Lara, M.G.; Osuna-Fernandez, H.R.; Jimenez-Estrada, M.J.A.b.m. Five anti-inflammatory plant species of the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis from Mexico, 1552: A botanical, chemical and pharmacological review. Acta Botánica Mex. 2023, 130, e2137. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa-Gómez, C.I.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; Pérez, M.D.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.R.; Flores-Rueda, A.G.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E. Antioxidant and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Litsea glaucescens Infusions Fermented with Kombucha Consortium. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 54, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pobłocka-Olech, L.; Inkielewicz-Stepniak, I.; Krauze-Baranowska, M. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of the buds from different species of Populus in human gingival fibroblast cells: Role of bioflavanones. Phytomedicine 2019, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, K.; Nonaka, M.; Narahara, M.; Torii, I.; Kawaguchi, K.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kumazawa, Y.; Morikawa, S. Inhibitory effect of quercetin on carrageenan-induced inflammation in rats. Life Sci. 2003, 74, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simão da Silva, K.A.B.; Klein-Junior, L.C.; Cruz, S.M.; Cáceres, A.; Quintão, N.L.M.; Monache, F.D.; Cechinel-Filho, V. Anti-inflammatory and anti-hyperalgesic evaluation of the condiment laurel (Litsea guatemalensis Mez.) and its chemical composition. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1980–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.A.; Barillas, W.; Gomez-Laurito, J.; Lin, F.T.; Al-Rehaily, A.J.; Sharaf, M.H.; Schiff, P.L., Jr. Flavonoids from Litsea glaucescens. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Romero, J.C.; González-Ríos, H.; Peña-Ramos, A.; Velazquez, C.; Navarro, M.; Robles-Zepeda, R.; Martínez-Benavidez, E.; Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Virués, C.; Olivares, J.L.; et al. Seasonal Effect on the Biological Activities of Litsea glaucescens Kunth Extracts. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 2738489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, A.; Viesca, C.; Sánchez, G.; Sánchez, G.; Ramos de Viesca, M.; Sanfilippo, J. La materia médica en el Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis. Rev. Fac. Med. 2003, 46, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo, E.C.; De la Cruz, M.; Badiano, J. Valor médico y documental del manuscrito. In De la Cruz M. Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis. Manuscrito Azteca de 1552. Según Traducción Latina de Juan Badiano; Versión española con estudios y comentarios por diversos autores; Fondo de Cultura Económica-Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social: México City, Mexico, 1991; Volume 2, pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, F.; Valdés, J.; De la Cruz, M. Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis. Manuscrito azteca de 1552. Según traducción latina de Juan Badiano; Versión española con estudios y comentarios por diversos autores; Fondo de Cultura Económica-Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social: Mexico City, México, 1991; pp. 107–148. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, J.; Flores, H.; Ochoterena, H. La botánica en el Códice de la Cruz; Fondo de Cultura Económica-Instituto Mexicano del SeguroSocial: Mexico City, México, 1992; pp. 129–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ilia, H. Validación Farmacológica del Efecto Antiinflamatorio, de Hoja de Solanum hartwegii Benth. (Huiz), de Hoja de Litsea guatemalensis Mez. (Laurel), y de Hoja de Piper jacquemontianum Kunth. (Cordoncillo). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala City, Guatemala, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lorea-Hernández, F.; Jiménez-Pérez, N. Lauraceae. Flora Val. Tehuacán-Cuicatlán 2010, 82, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, A.O.; Janick, J. Flora of the Codex Cruz-Badianus; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chavarría, A.; Espinosa, G. Cruz-Badiano codex and the importance of the Mexican medicinal plants. J. Pharm. Technol. Res. Manag. 2019, 7, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y. The genus Litsea: A comprehensive review of traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities and other studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 334, 118494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Pan, T.; Zhu, A.-L.; Zhang, M.-H. Anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic properties of naringenin via attenuation of NF-κB and activation of the heme oxygenase (HO)-1/related factor 2 pathway. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017, 69, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.M.; Azab, S.S.; Saeed, N.M.; El-Demerdash, E. Antifibrotic Mechanism of Pinocembrin: Impact on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and TGF-β /Smad Inhibition in Rats. Ann. Hepatol. 2018, 17, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Shi, Y.; Wang, S.; Gao, C.J.P.O. Kaempferol inhibits oxidative stress and reduces macrophage pyroptosis by activating the NRF2 signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, G.; Sun, C.; Peng, F.; Yu, L.; Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Cao, X.; Tang, Y.; Xie, X.J.P.R. Chemistry, pharmacokinetics, pharmacological activities, and toxicity of Quercitrin. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 1545–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, G.; Al-Kahtani, M.A.; El-Sayed, W.M. Anti-inflammatory and Anti-oxidant Properties of Curcuma longa (Turmeric) Versus Zingiber officinale (Ginger) Rhizomes in Rat Adjuvant-Induced Arthritis. Inflammation 2011, 34, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, L.; Vásquez, A.; Marroquín, N.; Guerra, L.; Cruz, S.M.; Cáceres, A. In silico Molecular Docking Analysis of Three Molecules Isolated from Litsea guatemalensis Mez on Anti-inflammatory Receptors. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2024, 27, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Gibson, S.A.; Buckley, J.A.; Qin, H.; Benveniste, E.N. Role of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in regulation of innate immunity in neuroinflammatory diseases. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 189, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: From bench to clinic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, M.P.Y.; Samsul, R.N.; Mohaimin, A.W.; Goh, H.P.; Zaini, N.H.; Kifli, N.; Ahmad, N. The Analgesic Potential of Litsea Species: A Systematic Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Young, L.M.; Kheifets, J.B.; Ballaron, S.J.; Young, J.M. Edema and cell infiltration in the phorbol ester-treated mouse ear are temporally separate and can be differentially modulated by pharmacologic agents. Agents Actions 1989, 26, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkhaleq, L.A.; Assi, M.A.; Abdullah, R.; Zamri-Saad, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Hezmee, M.N.M. The crucial roles of inflammatory mediators in inflammation: A review. Vet. World 2018, 11, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, W.; Basit, H.; Burns, B. Pathology, Inflammation; StatPeals: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Calhelha, R.C.; Haddad, H.; Ribeiro, L.; Heleno, S.A.; Carocho, M.; Barros, L. Inflammation: What’s There and What’s New? Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrimpe, A.C.; Wright, D.W. Differential gene expression mediated by 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Malar. J. 2009, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Piao, M.; Song, Y.; Liu, C. Quercetin Suppresses AOM/DSS-Induced Colon Carcinogenesis through Its Anti-Inflammation Effects in Mice. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 9242601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Wu, J.; Lyu, S.; Guo, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hou, T. Protective effect of quercetin against macrophage-mediated hepatocyte injury via anti-inflammation, anti-apoptosis and inhibition of ferroptosis. Autoimmunity 2024, 57, 2350202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, J.; Miao, Z.; Jiang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, G. Quercitrin improved cognitive impairment through inhibiting inflammation induced by microglia in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Neuroreport 2022, 33, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comalada, M.; Camuesco, D.; Sierra, S.; Ballester, I.; Xaus, J.; Gálvez, J.; Zarzuelo, A. In vivo quercitrin anti-inflammatory effect involves release of quercetin, which inhibits inflammation through down-regulation of the NF-kappaB pathway. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005, 35, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, P.; Thangam, E.B. Vitex trifolia L. modulates inflammatory mediators via down-regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in carrageenan-induced acute inflammation in experimental rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 298, 115583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wu, C.; Hu, K. Tissue plasminogen activator activates NF-κB through a pathway involving annexin A2/CD11b and integrin-linked kinase. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, S.F.; Abdel Mageed, S.S.; Mahmoud, A.M.A.; El-Demerdash, A.A.; Doghish, A.S.; Azzam, R.K.; Mohamed, R.E.; Farouk, E.A.; Noshy, M.; Shakweer, M.M.; et al. Pinocembrin protects against cisplatin-induced liver injury via modulation of oxidative stress, TAK-1 inflammation, and apoptosis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 502, 117433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Du, Q.; Shen, H.; Zhu, Z. Pinocembrin attenuates allergic airway inflammation via inhibition of NF-κB pathway in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 53, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, F.A.B.; Rivas, I.G.; Santos, L.C.; Almanza, M.S.O. Uso actual de las plantas del Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis o Códice de la Cruz-Badiano en México. An. Jardin Botánico Madr. 2023, 80, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argueta, A.; Vázquez, M.C.G. Atlas de las Plantas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana; Instituto Nacional Indigenista: Mexico City, Mexico, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- NOM-062-ZOO-1999; Especificaciones Técnicas Para la Producción, Cuidado y Uso de los Animales de Laboratorio. NORMA Oficial Mexicana: Mexico City, Mexico, 1999. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/203498/NOM-062-ZOO-1999_220801.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- NOM-087-SEMARNAT-SSA1-2002; Protección Ambiental—Salud Ambiental—Residuos Peligrosos Biológico-Infecciosos—Lasificación y Especificaciones de Manejo. NORMA Oficial Mexicana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2002. Available online: https://www.cndh.org.mx/sites/default/files/doc/Programas/VIH/Leyes%20y%20normas%20y%20reglamentos/Norma%20Oficial%20Mexicana/NOM-087-SEMARNAT-SSA1-2002%20Proteccion%20ambiental-salud.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources; Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Revised in 2011. Available online: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/guide-for-the-care-and-use-of-laboratory-animals.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Morris, C.J. Carrageenan-induced paw edema in the rat and mouse. Methods Mol. Biol. 2003, 225, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posadas, I.; Bucci, M.; Roviezzo, F.; Rossi, A.; Parente, L.; Sautebin, L.; Cirino, G. Carrageenan-induced mouse paw oedema is biphasic, age-weight dependent and displays differential nitric oxide cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 142, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.P.; Priebat, D.A.; Christensen, R.D.; Rothstein, G. Measurement of cutaneous inflammation: Estimation of neutrophil content with an enzyme marker. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1982, 78, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Ota, H.; Sasagawa, S.; Sakatani, T.; Fujikura, T. Assay method for myeloperoxidase in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anal. Biochem. 1983, 132, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, M.; Nieto, A.; Marin, J.C.; Keck, A.S.; Jeffery, E.; Céspedes, C.L. Antioxidant activities of extracts from Barkleyanthus salicifolius (Asteraceae) and Penstemon gentianoides (Scrophulariaceae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5889–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterborg, J.H.; Matthews, H.R. The lowry method for protein quantitation. Methods Mol. Biol. 1984, 1, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenane, D.; Aboudaou, M.; Ferhat, M.A.; Ouelhadj, A.; Ariño, A.J.J.o.E.O.R. Effect of the aromatisation with summer savory (Satureja hortensis L.) essential oil on the oxidative and microbial stabilities of liquid whole eggs during storage. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2019, 31, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | of Ears Left, Weight ± SEM (mg) Without TPA | of Ears Right, Weight ± SEM (mg) with TPA |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanolic solution | 13.7 ± 0.6 | 28.6 ± 0.7 |

| Indomethacin (1 mg/ear) | 12.8 ± 0.6 | 18.4 ± 2.0 |

| GLAM (1 mg/ear) | 11.4 ± 0.2 | 22.0 ± 1.3 |

| GUAM (1 mg/ear) | 13.3 ± 0.8 | 25.5 ± 0.9 |

| Treatment | ± SEM |

|---|---|

| Ethanolic solution (basal) | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| Ethanolic solution + TPA | 1.25 ± 0.19 |

| Indomethacin (1 mg/ear) + TPA | 0.33 ± 0.19 |

| GLAM (1 mg/ear) + TPA | 0.31 ± 0.11 |

| GUAM (1 mg/ear) + TPA | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

| Concentration (µg/mL) | ± SEM | |

|---|---|---|

| GLAM | GUAM | |

| 0 | 0.64 ± 0.003 | 0.64 ± 0.003 |

| 5.62 | 0.57 ± 0.002 | 0.57 ± 0.001 |

| 10 | 0.52 ± 0.002 | 0.51 ± 0.002 |

| 17.78 | 0.43 ± 0.001 | 0.42 ± 0.001 |

| 31.62 | 0.30 ± 0.004 | 0.28 ± 0.002 |

| 56.23 | 0.1 ± 0.004 | 0.1 ± 0.002 |

| 100 | 0.0 ± 0.0007 | 0.0 ± 0.001 |

| Concentration (µg/mL) | ± SEM | |

|---|---|---|

| GLAM | GUAM | |

| Basal | 0.70 ± 0.25 | 0.70 ± 0.25 |

| FeSO4 | 10.53 ± 0.47 | 10.53 ± 0.47 |

| 5.62 | 9.22 ± 0.45 | 9.16 ± 0.53 |

| 10 | 8.81 ± 0.49 | 8.85 ± 0.45 |

| 17.78 | 7.69 ± 0.39 | 7.67 ± 0.46 |

| 31.62 | 5.62 ± 0.33 | 6.07 ± 0.41 |

| 56.23 | 2.05 ± 0.37 | 2.28 ± 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

López-Miranda, D.Y.; Reyes-Chilpa, R.; Nieto-Camacho, A.; Guzmán-Gutiérrez, S.L.; Barrera-Vázquez, O.S.; Jiménez-Mendoza, M.S.; García-Ríos, E.; Magos-Guerrero, G.A. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activity of Litsea glaucescens Kunth in Rodents, an Aztec Medicinal Plant Used in Pre-Columbian Times. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010040

López-Miranda DY, Reyes-Chilpa R, Nieto-Camacho A, Guzmán-Gutiérrez SL, Barrera-Vázquez OS, Jiménez-Mendoza MS, García-Ríos E, Magos-Guerrero GA. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activity of Litsea glaucescens Kunth in Rodents, an Aztec Medicinal Plant Used in Pre-Columbian Times. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Miranda, Dulce Yehimi, Ricardo Reyes-Chilpa, Antonio Nieto-Camacho, Silvia Laura Guzmán-Gutiérrez, Oscar Salvador Barrera-Vázquez, María Sofía Jiménez-Mendoza, Eréndira García-Ríos, and Gil Alfonso Magos-Guerrero. 2026. "Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activity of Litsea glaucescens Kunth in Rodents, an Aztec Medicinal Plant Used in Pre-Columbian Times" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010040

APA StyleLópez-Miranda, D. Y., Reyes-Chilpa, R., Nieto-Camacho, A., Guzmán-Gutiérrez, S. L., Barrera-Vázquez, O. S., Jiménez-Mendoza, M. S., García-Ríos, E., & Magos-Guerrero, G. A. (2026). Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activity of Litsea glaucescens Kunth in Rodents, an Aztec Medicinal Plant Used in Pre-Columbian Times. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010040