C16-siRNAs in Focus: Development of ALN-APP, a Promising RNAi-Based Therapeutic for Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

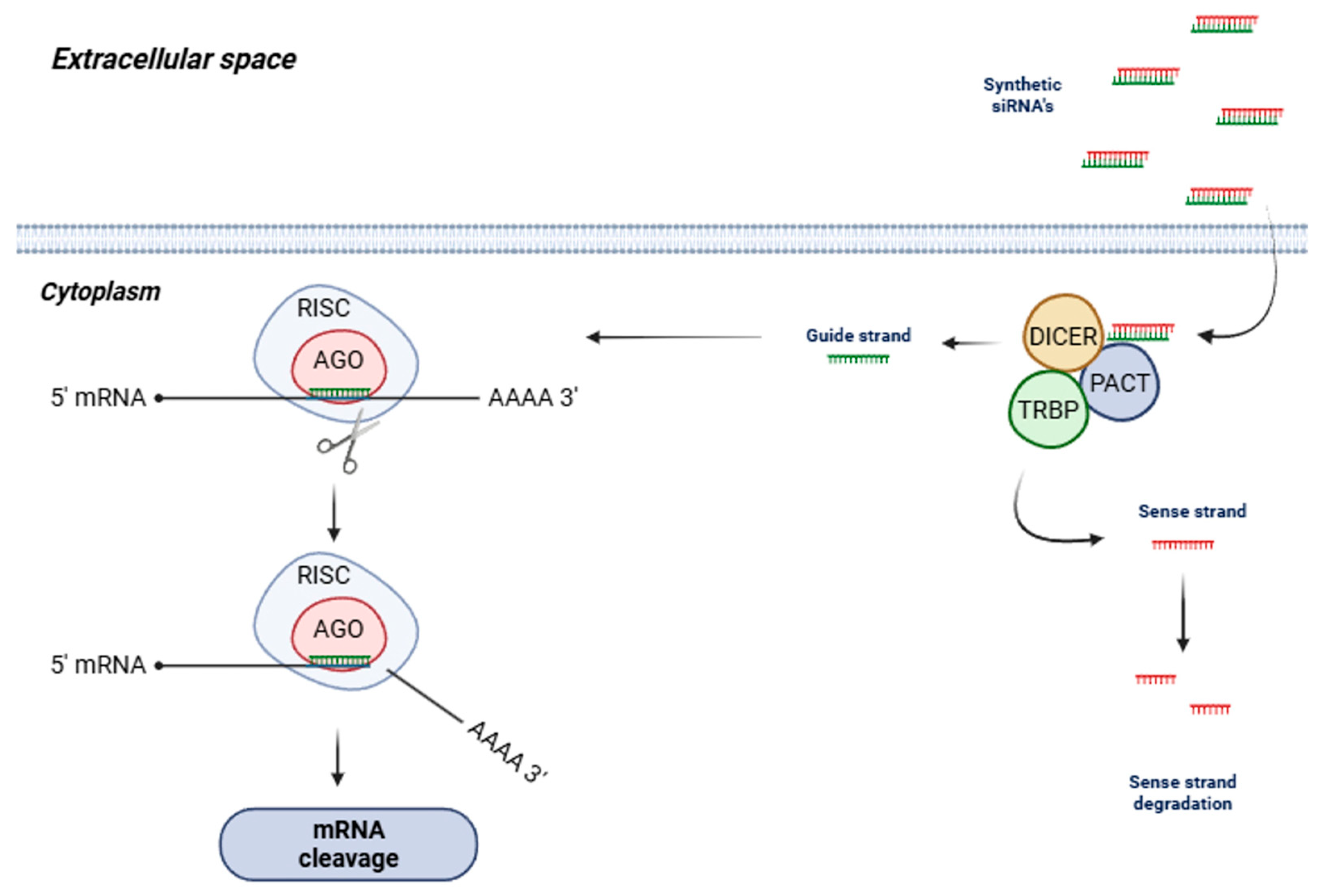

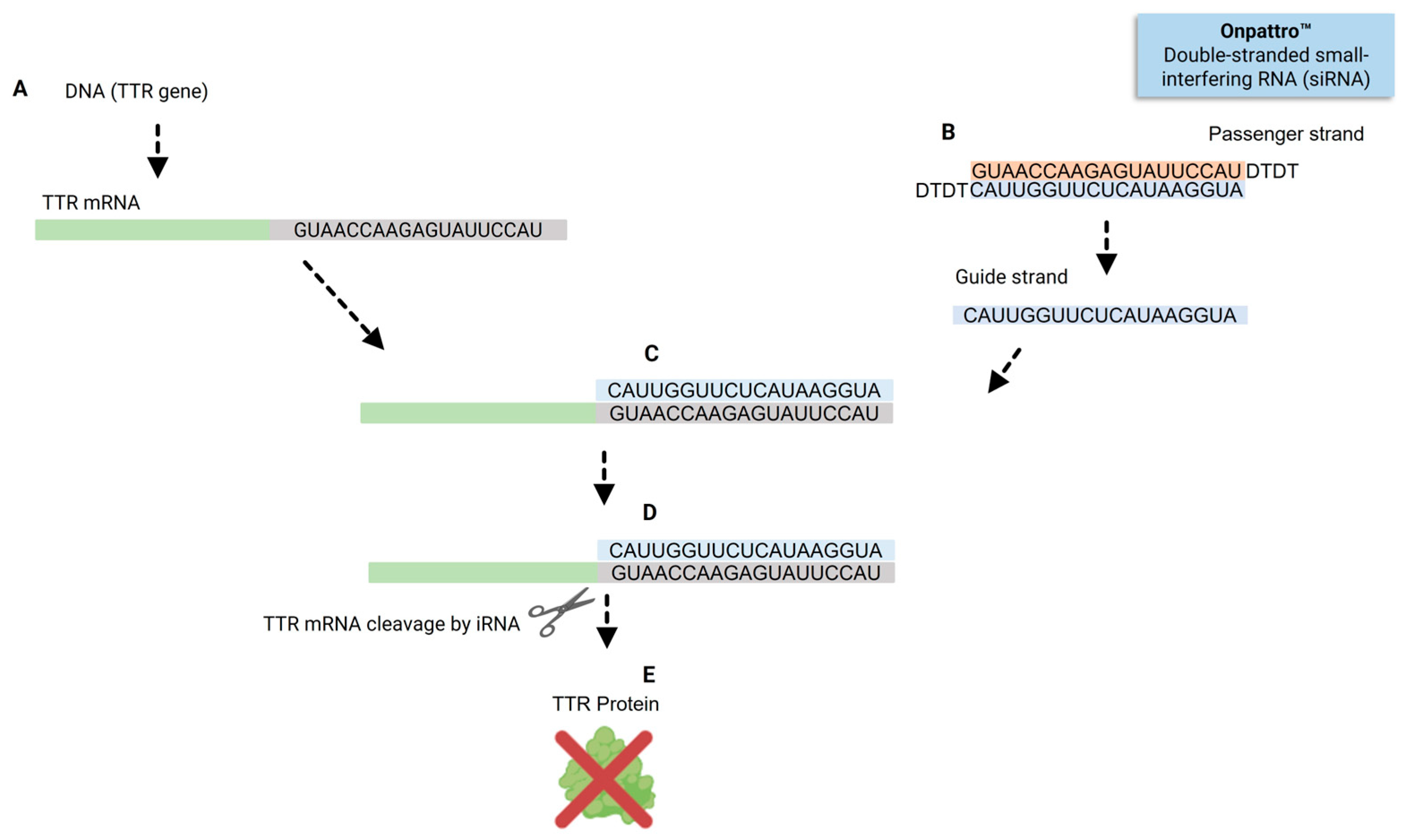

2. siRNAs—Concept and Mechanism of Action

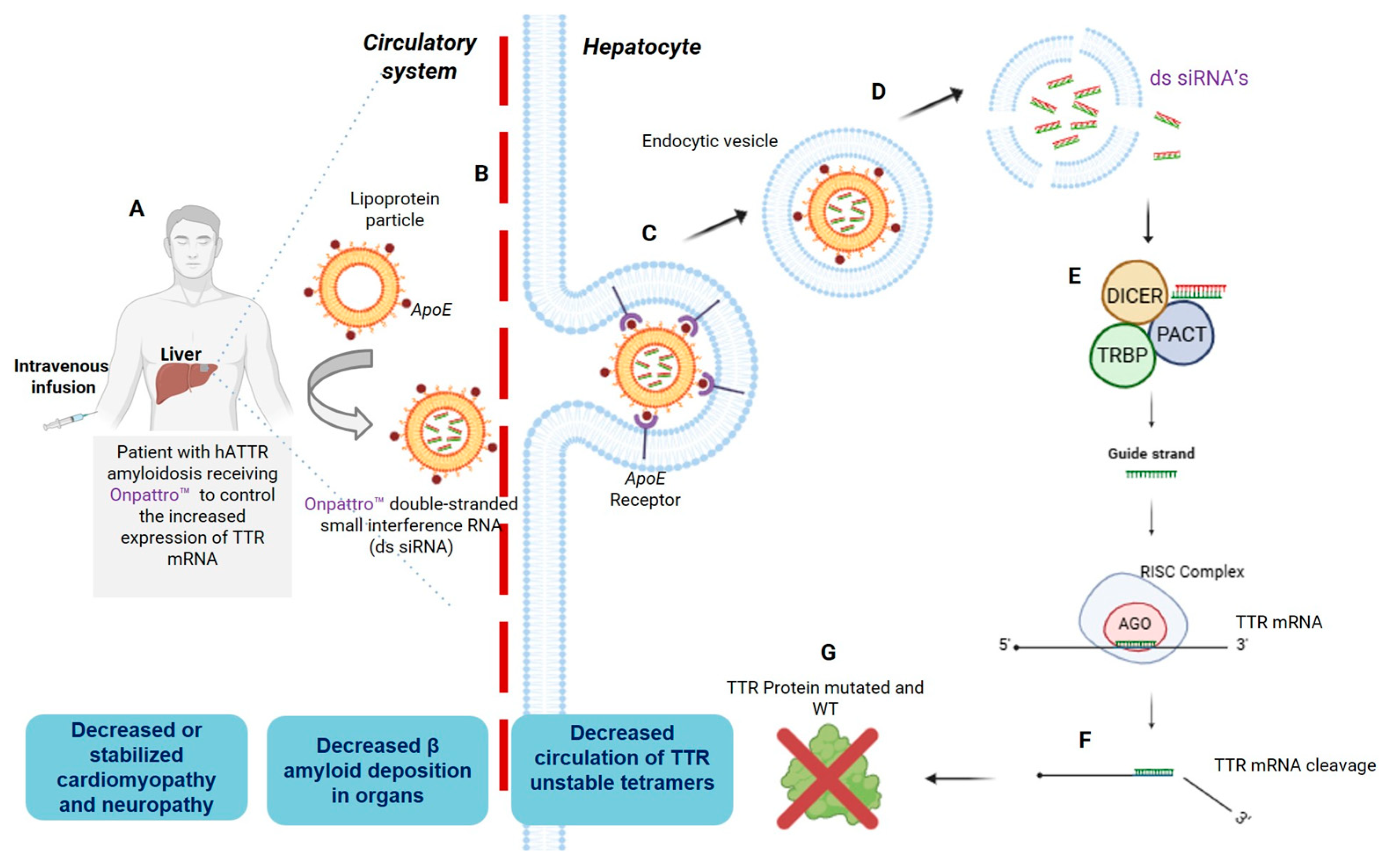

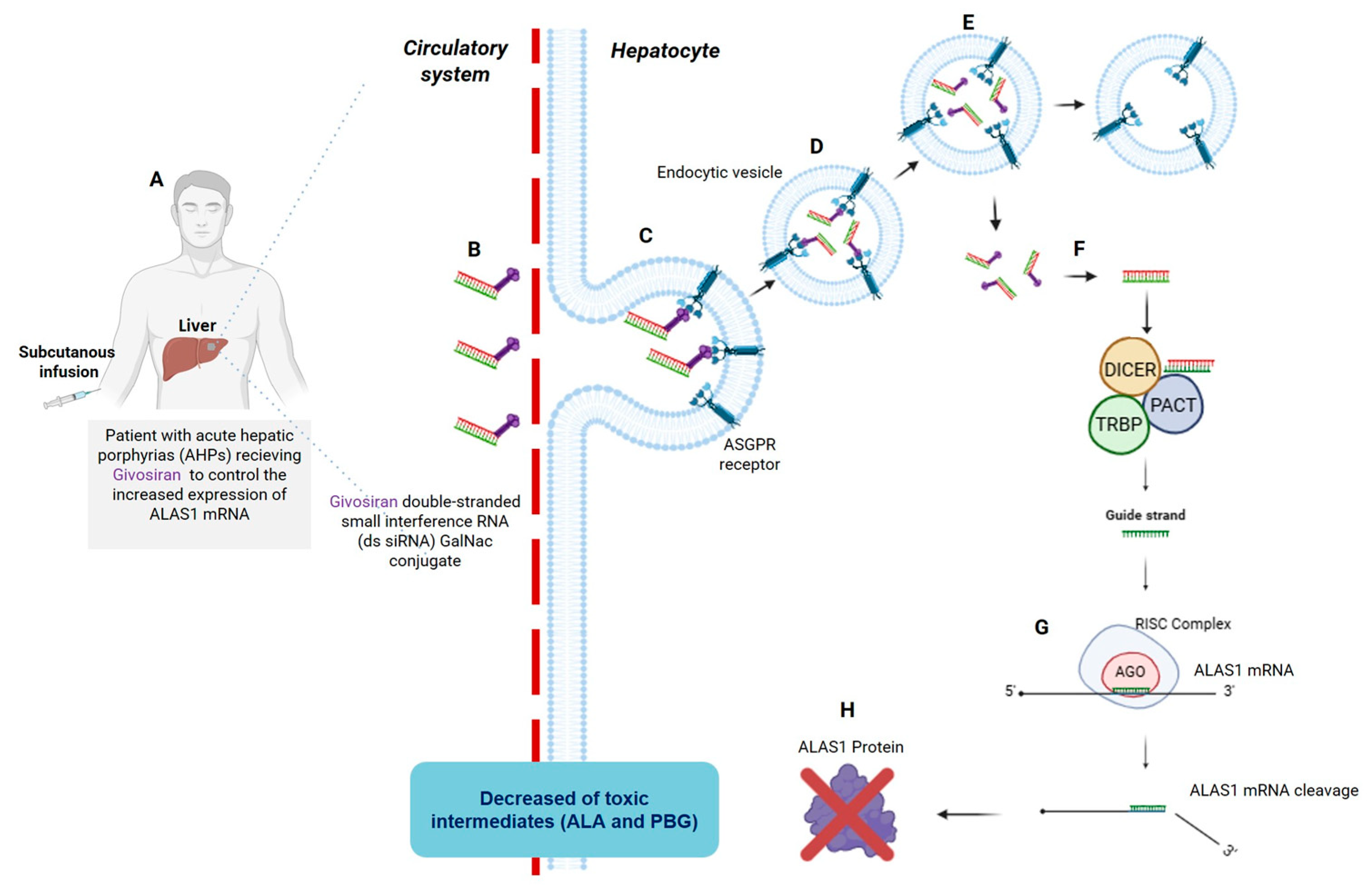

3. A Brief Overview of Patisiran and Givosiran Biotechnology: The First Two FDA-Approved siRNAs Demonstrating Organ-Specific Delivery Viability

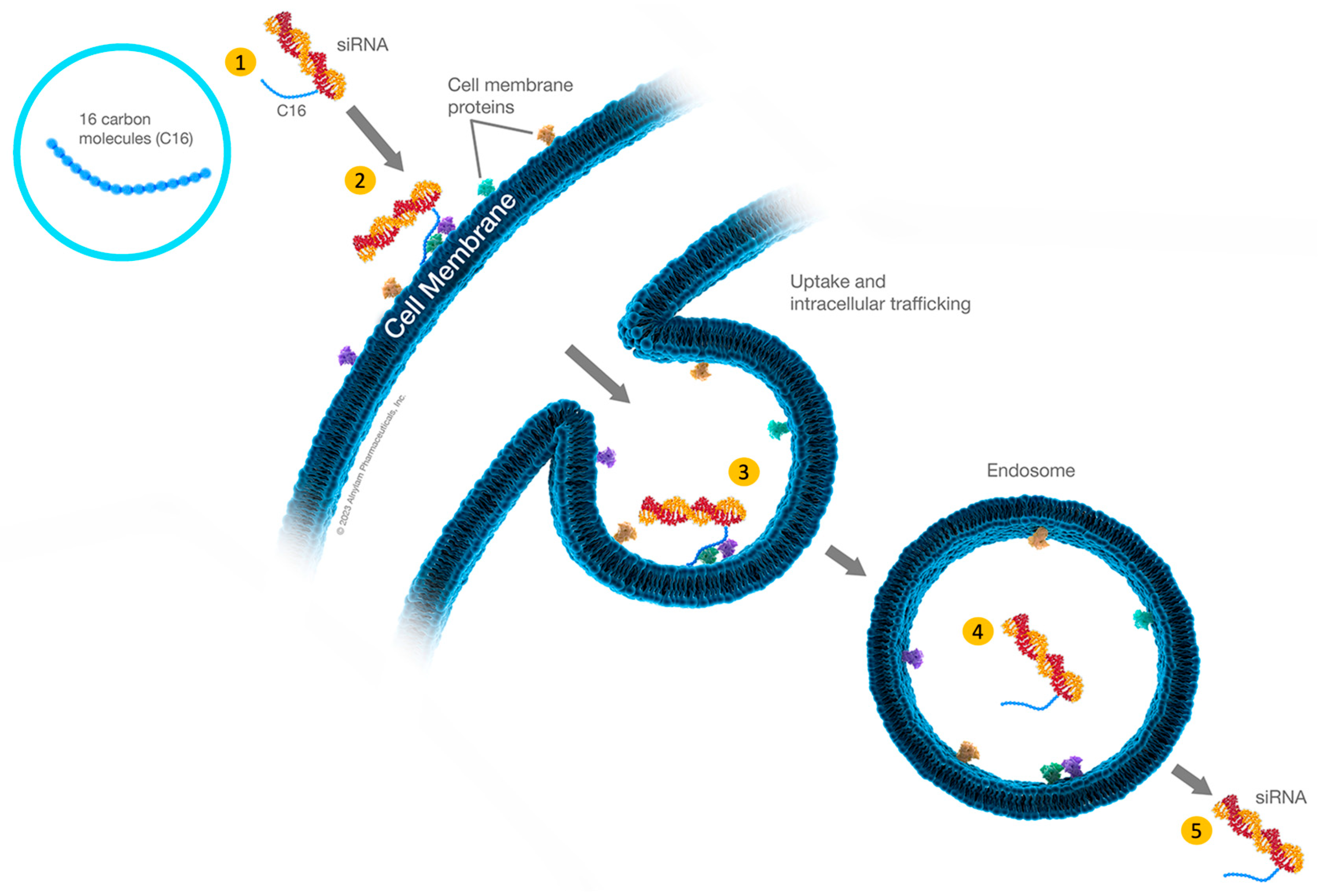

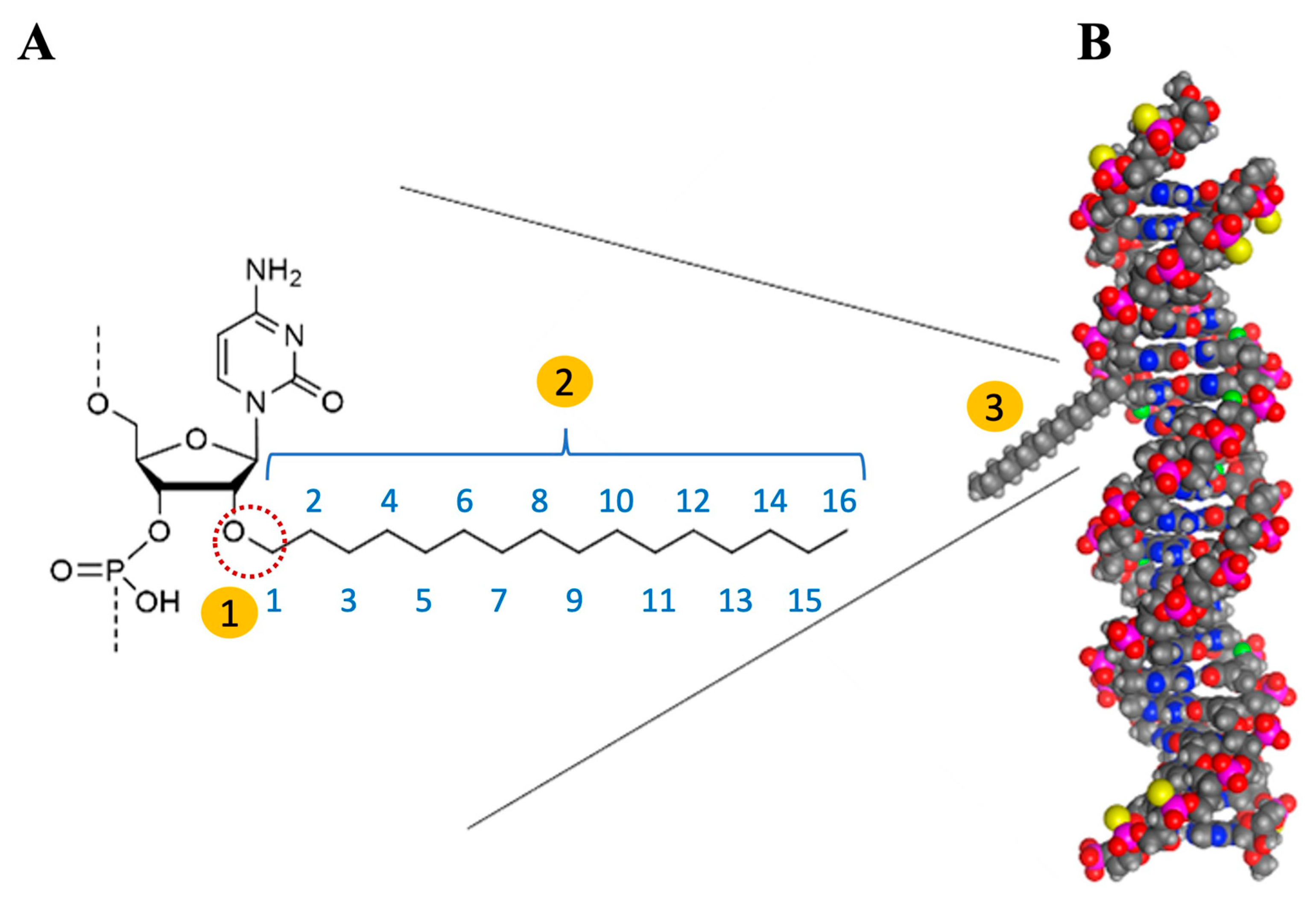

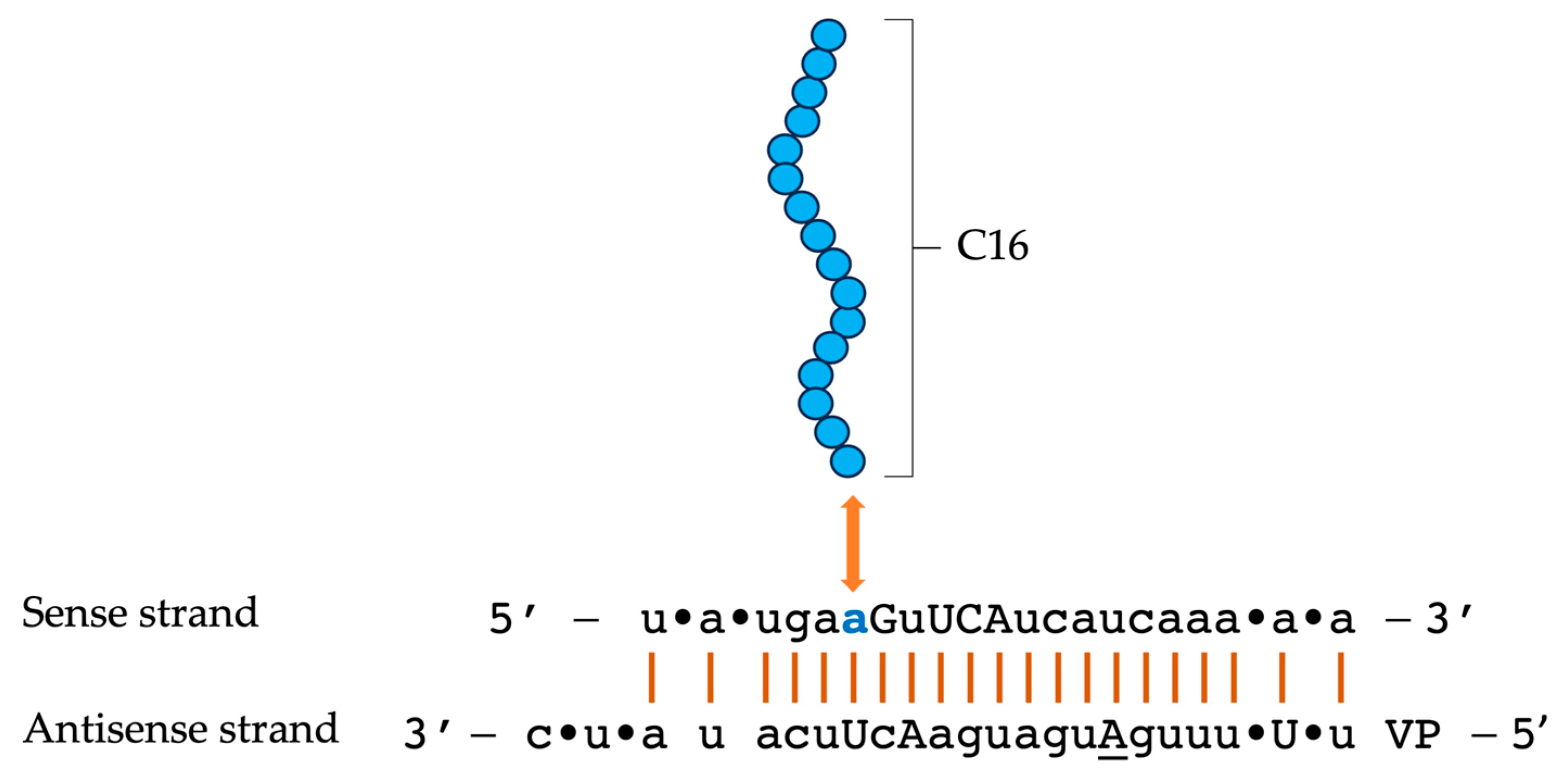

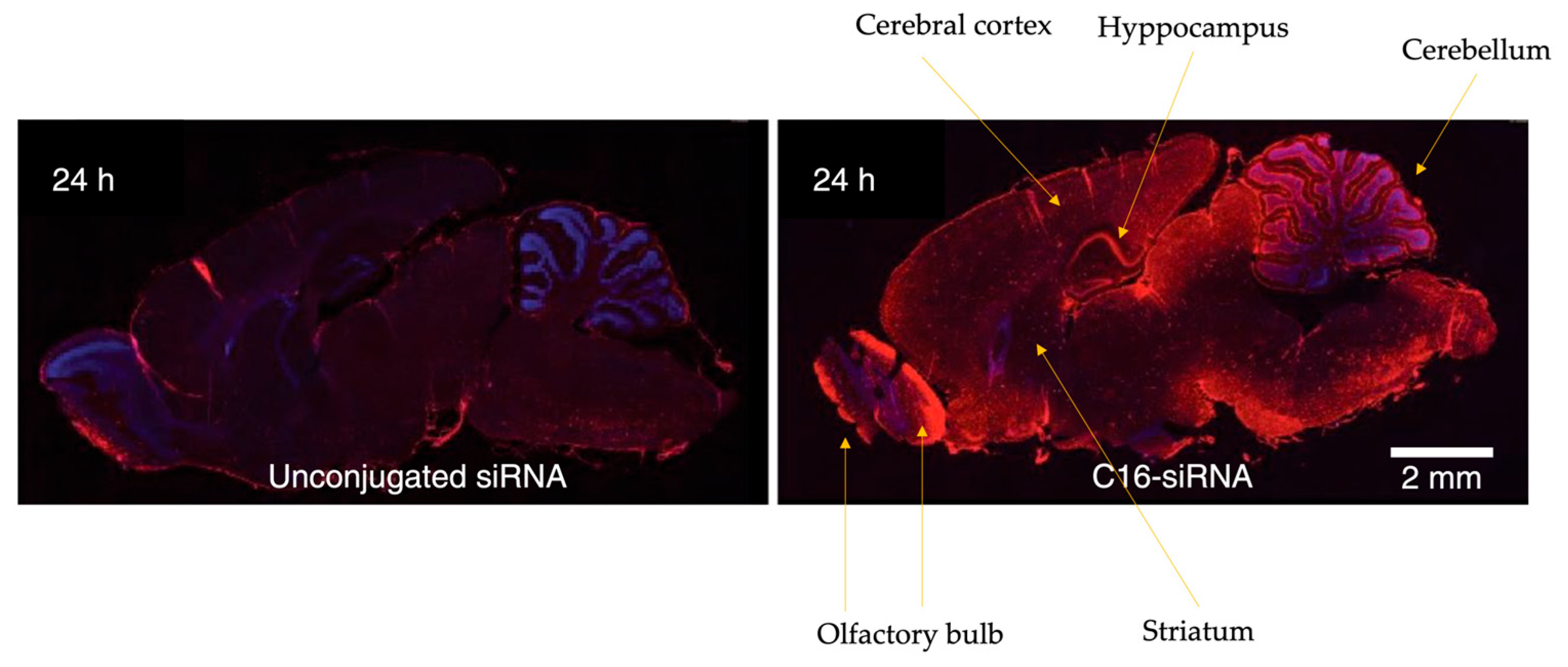

4. C16-siRNAs

Innovations in the Design of Brain-Delivered C16-siRNAs: A Functional Perspective

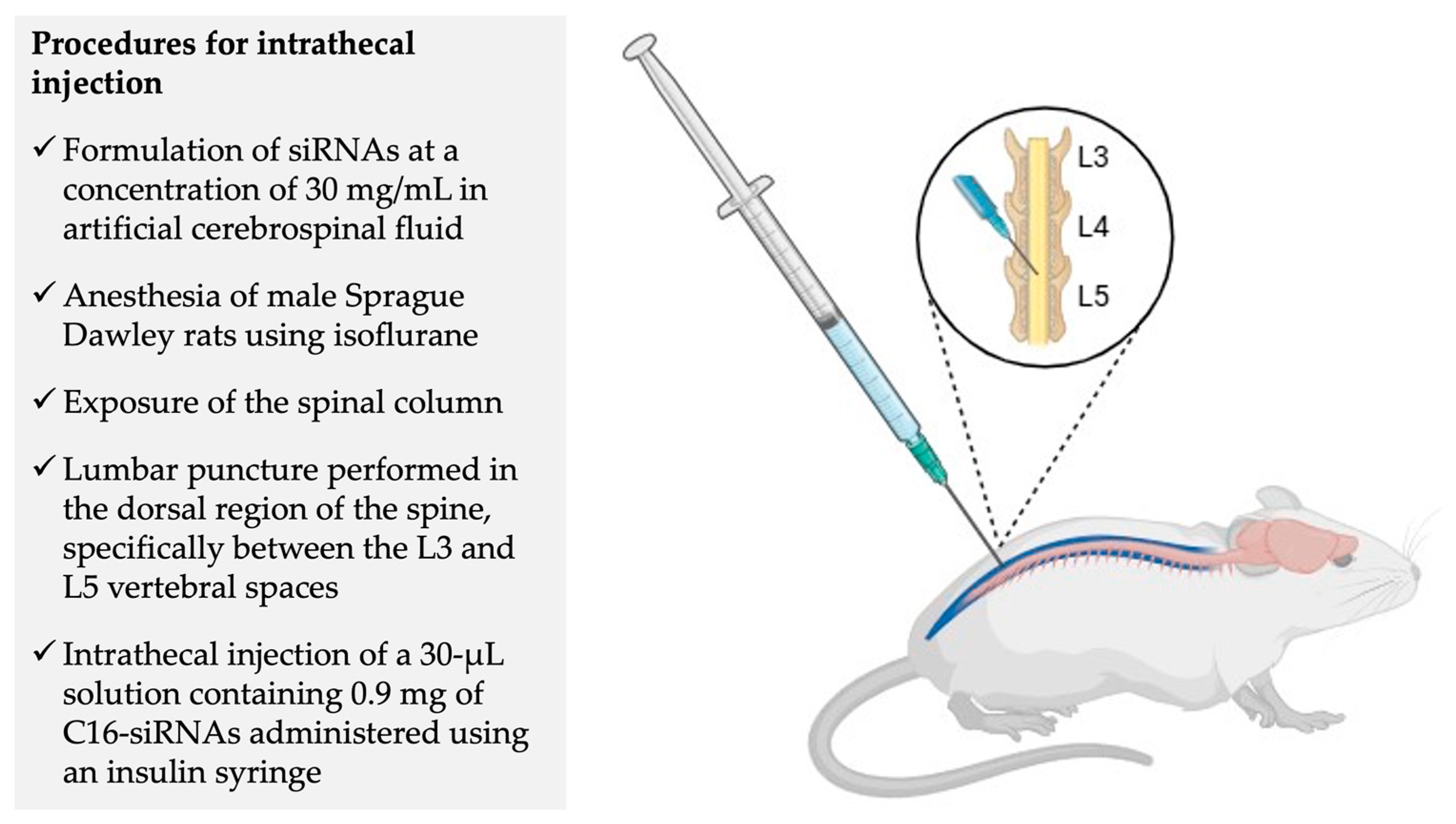

5. Phase 1 Clinical Trial—NCT05231785: Experimental Design and Preliminary Results

6. A Critical Analysis of Disease Phenotypes and Animal Models Used in Preclinical Studies

7. Analysis of Dose-Escalation Testing on Silencing Effects and Tolerability in Clinical and Preclinical Studies

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAIC | Alzheimer’s Association International Conference |

| aCSF | Artificial cerebrospinal fluid |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AEs | Adverse events |

| AGO2 enzyme | Argonaute 2 enzyme |

| AHP | Acute hepatic porphyria |

| ALA | δ-aminolevulinic acid |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| APP | Amyloid precursor protein |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| ARIA-H | Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities-hemosiderin |

| ASGPR | Asialoglycoprotein receptor |

| Aβ | β-amyloid |

| AV | Autophagic vacuole |

| CAA | Cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

| CDR | Clinical dementia rating |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CVN | Cerebrovascular amyloid Nos2−/−, a genetically modified mouse used to study Alzheimer’s disease |

| DEAF1 | Deformed epidermal autoregulatory factor-1 |

| ds-siRNA | Double-stranded siRNA |

| EOAD | Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GalNAc | N-acetylgalactosamine |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GNA | Glycol nucleic acid |

| hATTR | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis |

| ICV | Intracerebroventricular |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IN | Intranasal |

| IT | Intrathecal |

| IV | Intravenous |

| IVT | Intravitreal |

| LNP | Lipid nanoparticle |

| LRP1 | Lipoprotein receptor-related protein |

| MAD | Multiple ascending dose |

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NfL | Neurofilament light chain |

| NFT’s | Neurofibrillary tangles |

| NHPs | Non-human primates |

| NMDA | N-methyl D-aspartate |

| mAbs | Monoclonal antibodies |

| MSD | Meso-scale discovery |

| MTD | Maximum tolerated dose |

| PACT | Protein activator of the interferon-induced protein kinase |

| PBG | Porphobilinogen |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| PS | Phosphorothioate |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| ROS | Reative oxygen species |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcriptase—quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SAD | Single ascending dose |

| sAPPα | Soluble APPα |

| sAPPβ | Soluble APPβ |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| Sod1 | Superoxide dismutase 1 |

| SR-BI | Scavenger receptor B type I |

| TRBP | Transactivation response RNA-binding protein |

| TTR | Transthyretin |

| TTR-FAP | Transthyretin familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy |

| VLDLR | Very low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| VP | Vinylphosphonate, metabolic stable analog phosphate modification. Added to avoid phosphatase degradation |

| Wt | Wild type |

References

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A.; Jones, D.T. Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the Global Prevalence of Dementia in 2019 and Forecasted Prevalence in 2050: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madnani, R.S. Alzheimer’s Disease: A Mini-Review for the Clinician. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1178588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Villain, N.; Frisoni, G.B.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Sabbagh, M.; Cappa, S.; Bejanin, A.; Bombois, S.; Epelbaum, S.; Teichmann, M.; et al. Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations of the International Working Group. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Ren, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Qiao, W.; Li, F.; Felton, L.M.; Mahmoudiandehkordi, S.; Kueider-Paisley, A.; Sonoustoun, B.; Arnold, M.; et al. Alzheimer’s Risk Factors Age, APOE Genotype, and Sex Drive Distinct Molecular Pathways. Neuron 2020, 106, 727–742.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.B. A Brief History of the Progress in Our Understanding of Genetics and Lifestyle, Especially Diet, in the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 100, S165–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordestgaard, L.T.; Christoffersen, M.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Shared Risk Factors between Dementia and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.-F.; Jiang, T.; Tan, M.-S.; Tan, L.; Zhao, Q.-F.; Li, J.-Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.-T. Meta-Analysis of Modifiable Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 1284–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Q.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.-F.; Tan, M.-S.; Tan, L.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Q.-F.; Wang, J.; Jiang, T.; Yu, J.-T. Risk Factors for Predicting Progression from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Vemuri, P. Resistance vs Resilience to Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2018, 90, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkle, B.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Sims, R.; Bis, J.C.; Damotte, V.; Naj, A.C.; Boland, A.; Vronskaya, M.; van der Lee, S.J.; Amlie-Wolf, A.; et al. Genetic Meta-Analysis of Diagnosed Alzheimer’s Disease Identifies New Risk Loci and Implicates Aβ, Tau, Immunity and Lipid Processing. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsell, S.E.; Mock, C.; Fardo, D.W.; Bertelsen, S.; Cairns, N.J.; Roe, C.M.; Ellingson, S.R.; Morris, J.C.; Goate, A.M.; Kukull, W.A. Genetic Comparison of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Persons with Alzheimer Disease Neuropathology. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2017, 31, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prpar Mihevc, S.; Majdič, G. Canine Cognitive Dysfunction and Alzheimer’s Disease—Two Facets of the Same Disease? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panek, W.K.; Murdoch, D.M.; Gruen, M.E.; Mowat, F.M.; Marek, R.D.; Olby, N.J. Plasma Amyloid Beta Concentrations in Aged and Cognitively Impaired Pet Dogs. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, D.R.; Capetillo-Zarate, E.; Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. The Development of Amyloid β Protein Deposits in the Aged Brain. Sci. Aging Knowl. Environ. 2006, 2006, re1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.T.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association Guidelines for the Neuropathologic Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2012, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montine, T.J.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Mirra, S.S.; et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association Guidelines for the Neuropathologic Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Practical Approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Lopez, J.A.; Yachnis, A.T.; Prokop, S. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The Neuropathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, B.J.; Su, J.H.; Cotman, C.W.; White, R.; Russell, M.J. β-Amyloid Accumulation in Aged Canine Brain: A Model of Early Plaque Formation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 1993, 14, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czasch, S.; Paul, S.; Baumgärtner, W. A Comparison of Immunohistochemical and Silver Staining Methods for the Detection of Diffuse Plaques in the Aged Canine Brain. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, K.A.; Sohrabi, H.R.; Rodrigues, M.; Beilby, J.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Taddei, K.; Criddle, A.; Wraith, M.; Howard, M.; Martins, G.; et al. Association of Cardiovascular Factors and Alzheimer’s Disease Plasma Amyloid-β Protein in Subjective Memory Complainers. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2009, 17, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verghese, P.B.; Castellano, J.M.; Garai, K.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Shah, A.; Bu, G.; Frieden, C.; Holtzman, D.M. ApoE Influences Amyloid-β (Aβ) Clearance despite Minimal ApoE/Aβ Association in Physiological Conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E1807–E1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Guo, Z. Alzheimer’s Aβ42 and Aβ40 Peptides Form Interlaced Amyloid Fibrils. J. Neurochem. 2013, 126, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, T.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.F.; Li, Y.M. Aβ42 and Aβ40: Similarities and Differences. J. Pept. Sci. 2015, 21, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Watanabe, K.; Bryois, J.; Williams, D.M.; Steinberg, S.; Sealock, J.; Karlsson, I.K.; Hägg, S.; Athanasiu, L.; et al. Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies New Loci and Functional Pathways Influencing Alzheimer’s Disease Risk. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Yang, D.S.; Goulbourne, C.N.; Im, E.; Stavrides, P.; Pensalfini, A.; Chan, H.; Bouchet-Marquis, C.; Bleiwas, C.; Berg, M.J.; et al. Faulty Autolysosome Acidification in Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models Induces Autophagic Build-up of Aβ in Neurons, Yielding Senile Plaques. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargbo-Hill, S.E.; Colón-Ramos, D.A. The Journey of the Synaptic Autophagosome: A Cell Biological Perspective. Neuron 2020, 105, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A.; Wegiel, J.; Kumar, A.; Yu, W.H.; Peterhoff, C.; Cataldo, A.; Cuervo, A.M. Extensive Involvement of Autophagy in Alzheimer Disease: An Immuno-Electron Microscopy Study. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 64, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; McBrayer, M.K.; Wolfe, D.M.; Haslett, L.J.; Kumar, A.; Sato, Y.; Lie, P.P.Y.; Mohan, P.; Coffey, E.E.; Kompella, U.; et al. Presenilin 1 Maintains Lysosomal Ca2+ Homeostasis via TRPML1 by Regulating VATPase-Mediated Lysosome Acidification. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 1430–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.M.; Mayer, J.; Nilsson, P.; Shimozawa, M. How Close Is Autophagy-Targeting Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease to Clinical Use? A Summary of Autophagy Modulators in Clinical Studies. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 12, 1520949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhapola, R.; Kumari, S.; Sharma, P.; Paidlewar, M.; Medhi, B.; Vellingiri, B.; HariKrishnaReddy, D. Deciphering Molecular and Signaling Pathways of Extracellular Vesicles-Based Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 15430–15449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickford, F.; Masliah, E.; Britschgi, M.; Lucin, K.; Narasimhan, R.; Jaeger, P.A.; Small, S.; Spencer, B.; Rockenstein, E.; Levine, B.; et al. The Autophagy-Related Protein Beclin 1 Shows Reduced Expression in Early Alzheimer Disease and Regulates Amyloid β Accumulation in Mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 2190–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, J.Y.; Meng, X.L.; Yang, D.; Fan, L.H.; Xiang, L.; Wang, P. Traditional Chinese Medicine: Role in Reducing β-Amyloid, Apoptosis, Autophagy, Neuroinflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammineni, P.; Ye, X.; Feng, T.; Aikal, D.; Cai, Q. Impaired Retrograde Transport of Axonal Autophagosomes Contributes to Autophagic Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease Neurons. eLife 2017, 6, e21776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Benzinger, T.L.; Hassenstab, J.; Blazey, T.; Owen, C.; Liu, J.; Fagan, A.M.; Morris, J.C.; Ances, B.M. Spatially Distinct Atrophy Is Linked to β-Amyloid and Tau in Preclinical Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2015, 84, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Iyaswamy, A.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, C. Novel Insight into Functions of Transcription Factor EB (TFEB) in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 652–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagaria, J.; Bagyinszky, E.; An, S.S.A. Genetics, Functions, and Clinical Impact of Presenilin-1 (PSEN1) Gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sun, M. Autophagy and Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 37, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Trials and New Drug Development Strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Current and Future Treatments in Alzheimer Disease: An Update. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2020, 12, 1179573520907397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacorte, E.; Ancidoni, A.; Zaccaria, V.; Remoli, G.; Tariciotti, L.; Bellomo, G.; Sciancalepore, F.; Corbo, M.; Lombardo, F.L.; Bacigalupo, I.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Monoclonal Antibodies for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Published and Unpublished Clinical Trials. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 87, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanan, V.K.; Armstrong, M.J.; Choudhury, P.; Coerver, K.A.; Hamilton, R.H.; Klein, B.C.; Wolk, D.A.; Wessels, S.R.; Jones, L.K. Antiamyloid Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for Alzheimer Disease: Emerging Issues in Neurology. Neurology 2023, 101, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Osse, A.M.L.; Cammann, D.; Powell, J.; Chen, J. Anti-Amyloid Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. BioDrugs 2024, 38, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, G.; Tuschl, T. Mechanisms of Gene Silencing by Double-Stranded RNA. Nature 2004, 431, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and Specific Genetic Interference by Double-Stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titze-de-Almeida, R.; David, C.; Titze-de-Almeida, S.S. The Race of 10 Synthetic RNAi-Based Drugs to the Pharmaceutical Market. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 34, 1339–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.C.; Doudna, J.A. Molecular Mechanisms of RNA Interference. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 42, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthew, R.W.; Sontheimer, E.J. Origins and Mechanisms of MiRNAs and SiRNAs. Cell 2009, 136, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushati, N.; Cohen, S.M. MicroRNA Functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 23, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, P. Renaissance of Mammalian Endogenous RNAi. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 2550–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketting, R.F. The Many Faces of RNAi. Dev. Cell 2011, 20, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A.J.; MacRae, I.J. The RNA-Induced Silencing Complex: A Versatile Gene-Silencing Machine. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 17897–17901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Doudna, J.A. A Three-Dimensional View of the Molecular Machinery of RNA Interference. Nature 2009, 457, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamore, P.D. RNA Interference: Big Applause for Silencing in Stockholm. Cell 2007, 127, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamore, P.D.; Tuschl, T.; Sharp, P.A.; Bartel, D.P. RNAi: Double-Stranded RNA Directs the ATP-Dependent Cleavage of MRNA at 21 to 23 Nucleotide Intervals. Cell 2000, 101, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, M.; Aigner, A. Therapeutic siRNA: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. BioDrugs 2022, 36, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.I.E.; Zain, R. Therapeutic Oligonucleotides: State of the Art. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 59, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Suhr, O.B.; Hund, E.; Obici, L.; Tournev, I.; Campistol, J.M.; Slama, M.S.; Hazenberg, B.P.; Coelho, T. First European Consensus for Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment of Transthyretin Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2016, 29, S14–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H. Gene-Silencing Technology Gets First Drug Approval after 20-Year Wait. Nature 2018, 560, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikam, R.R.; Gore, K.R. Journey of SiRNA: Clinical Developments and Targeted Delivery. Nucleic Acid. Ther. 2018, 28, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paula Brandão, P.R.; Titze-de-Almeida, S.S.; Titze-de-Almeida, R. Leading RNA Interference Therapeutics Part 2: Silencing Delta-Aminolevulinic Acid Synthase 1, with a Focus on Givosiran. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 24, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullis, P.R.; Hope, M.J. Lipid Nanoparticle Systems for Enabling Gene Therapies. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J.A.; Cullis, P.R.; van der Meel, R. Lipid Nanoparticles Enabling Gene Therapies: From Concepts to Clinical Utility. Nucleic Acid. Ther. 2018, 28, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.; Gonzalez-Duarte, A.; O’Riordan, W.D.; Yang, C.C.; Ueda, M.; Kristen, A.V.; Tournev, I.; Schmidt, H.H.; Coelho, T.; Berk, J.L.; et al. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristen, A.V.; Ajroud-Driss, S.; Conceição, I.; Gorevic, P.; Kyriakides, T.; Obici, L. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic for the Treatment of Hereditary Transthyretin-Mediated Amyloidosis. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2019, 9, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titze-de-Almeida, S.S.; Brandão, P.R.d.P.; Faber, I.; Titze-de-Almeida, R. Leading RNA Interference Therapeutics Part 1: Silencing Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis, with a Focus on Patisiran. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 24, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, G. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of GalNAc-Conjugated SiRNAs. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 64, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.K.; Willoughby, J.L.S.; Chan, A.; Charisse, K.; Alam, M.R.; Wang, Q.; Hoekstra, M.; Kandasamy, P.; Kelin, A.V.; Milstein, S.; et al. Multivalent N-Acetylgalactosamine-Conjugated SiRNA Localizes in Hepatocytes and Elicits Robust RNAi-Mediated Gene Silencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16958–16961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, J.L.S.; Chan, A.; Sehgal, A.; Butler, J.S.; Nair, J.K.; Racie, T.; Shulga-Morskaya, S.; Nguyen, T.; Qian, K.; Yucius, K.; et al. Evaluation of GalNAc-SiRNA Conjugate Activity in Pre-Clinical Animal Models with Reduced Asialoglycoprotein Receptor Expression. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.M.; Nair, J.K.; Janas, M.M.; Anglero-Rodriguez, Y.I.; Dang, L.T.H.; Peng, H.; Theile, C.S.; Castellanos-Rizaldos, E.; Brown, C.; Foster, D.; et al. Expanding RNAi Therapeutics to Extrahepatic Tissues with Lipophilic Conjugates. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, A.E.; Gaus, H.J.; Berdeja, A.; Gupta, R.; Jo, M.; Prakash, T.P.; Oestergaard, M.; Swayze, E.E.; Seth, P.P. Mechanisms of Palmitic Acid-Conjugated Antisense Oligonucleotide Distribution in Mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 4382–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, V.; Maier, M. Expanding the Reach of RNAi Therapeutics with Next Generation Lipophilic SiRNA Conjugates. Available online: https://communities.springernature.com/posts/expanding-the-reach-of-rnai-therapeutics-with-next-generation-lipophilic-sirna-conjugates (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Alnylam Pharmaceutics, Inc. Alnylam. Delivery Platforms—C16 Conjugates. Available online: https://www.alnylam.com/our-science/sirna-delivery-platforms (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Gadhave, D.G.; Sugandhi, V.V.; Jha, S.K.; Nangare, S.N.; Gupta, G.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Cho, H.; Hansbro, P.M.; Paudel, K.R. Neurodegenerative Disorders: Mechanisms of Degeneration and Therapeutic Approaches with Their Clinical Relevance. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymeropoulos, M.H.; Lavedan, C.; Leroy, E.; Ide, S.E.; Dehejia, A.; Dutra, A.; Pike, B.; Root, H.; Rubenstein, J.; Boyer, R.; et al. Mutation in the α-Synuclein Gene Identified in Families with Parkinson’s Disease. Science 1997, 276, 2045–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabais Sá, M.J.; Jensik, P.J.; McGee, S.R.; Parker, M.J.; Lahiri, N.; McNeil, E.P.; Kroes, H.Y.; Hagerman, R.J.; Harrison, R.E.; Montgomery, T.; et al. De Novo and Biallelic DEAF1 Variants Cause a Phenotypic Spectrum. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassandri, M.; Smirnov, A.; Novelli, F.; Pitolli, C.; Agostini, M.; Malewicz, M.; Melino, G.; Raschellà, G. Zinc-Finger Proteins in Health and Disease. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.S. Structural Classification of Zinc Fingers: Survey and Summary. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, N.D.; Chung, W.K.; Sarmiere, P.D. RNA Interference (RNAi)-Based Therapeutics for Treatment of Rare Neurologic Diseases. Mol. Aspects Med. 2023, 91, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.; Huang, Y. Oligonucleotide Therapeutics for Neurodegenerative Diseases. NeuroImmune Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, C. Billion-Dollar Deal Propels RNAi to CNS Frontier. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 702–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won Lee, J.; Kyu Shim, M.; Kim, H.; Jang, H.; Lee, Y.; Hwa Kim, S. RNAi Therapies: Expanding Applications for Extrahepatic Diseases and Overcoming Delivery Challenges. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 201, 115073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, K.A.; Langer, R.; Anderson, D.G. Knocking down Barriers: Advances in SiRNA Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittrup, A.; Lieberman, J. Knocking down Disease: A Progress Report on SiRNA Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfrum, C.; Shi, S.; Jayaprakash, K.N.; Jayaraman, M.; Wang, G.; Pandey, R.K.; Rajeev, K.G.; Nakayama, T.; Charrise, K.; Ndungo, E.M.; et al. Mechanisms and Optimization of in Vivo Delivery of Lipophilic SiRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Butler, D.; Querbes, W.; Pandey, R.K.; Ge, P.; Maier, M.A.; Zhang, L.; Rajeev, K.G.; Nechev, L.; Kotelianski, V.; et al. Lipophilic SiRNAs Mediate Efficient Gene Silencing in Oligodendrocytes with Direct CNS Delivery. J. Control. Release 2010, 144, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soutschek, J.; Akinc, A.; Bramlage, B.; Charisse, K.; Constien, R.; Donoghue, M.; Elbashir, S.; Gelck, A.; Hadwiger, P.; Harborth, J.; et al. Therapeutic Silencing of an Endogenous Gene by Systemic Administration of Modified SiRNAs. Nature 2004, 432, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterman, J.F.; Hall, L.M.; Coles, A.H.; Hassler, M.R.; Didiot, M.C.; Chase, K.; Abraham, J.; Sottosanti, E.; Johnson, E.; Sapp, E.; et al. Hydrophobically Modified SiRNAs Silence Huntingtin MRNA in Primary Neurons and Mouse Brain. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2015, 4, e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, W. Chemical Modulation of SiRNA Lipophilicity for Efficient Delivery. J. Control. Release 2019, 307, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhong, L.; Weng, Y.; Peng, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, X.-J. Therapeutic siRNA: State of the art. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, L.L.; Owens, S.R.; Risen, L.M.; Lesnik, E.A.; Freier, S.M.; Mc Gee, D.; Cook, C.J.; Cook, P.D. Characterization of Fully 2’-Modified Oligoribonucleotide Hetero-and Homoduplex Hybridization Andnuclease Sensitivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 2019–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layzer, J.M.; McCaffrey, A.P.; Tanner, A.K.; Huang, Z.; Kay, M.A.; Sullenger, B.A. In Vivo Activity of Nuclease-Resistant SiRNAs. RNA 2004, 10, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Minakawa, N.; Matsuda, A. Synthesis and Characterization of 2′-Modified-4′-ThioRNA: A Comprehensive Comparison of Nuclease Stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerson, C.R.; Sioufi, N.; Jarres, R.; Prakash, T.P.; Naik, N.; Berdeja, A.; Wanders, L.; Griffey, R.H.; Swayze, E.E.; Bhat, B. Fully 2′-Modified Oligonucleotide Duplexes with Improved in Vitro Potency and Stability Compared to Unmodified Small Interfering RNA. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, T.P.; Kinberger, G.A.; Murray, H.M.; Chappell, A.; Riney, S.; Graham, M.J.; Lima, W.F.; Swayze, E.E.; Seth, P.P. Synergistic Effect of Phosphorothioate, 5′-Vinylphosphonate and GalNAc Modifications for Enhancing Activity of Synthetic SiRNA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 2817–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, D.J.; Brown, C.R.; Shaikh, S.; Trapp, C.; Schlegel, M.K.; Qian, K.; Sehgal, A.; Rajeev, K.G.; Jadhav, V.; Manoharan, M.; et al. Advanced SiRNA Designs Further Improve In Vivo Performance of GalNAc-SiRNA Conjugates. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janas, M.M.; Schlegel, M.K.; Harbison, C.E.; Yilmaz, V.O.; Jiang, Y.; Parmar, R.; Zlatev, I.; Castoreno, A.; Xu, H.; Shulga-Morskaya, S.; et al. Selection of GalNAc-Conjugated SiRNAs with Limited off-Target-Driven Rat Hepatotoxicity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegel, M.K.; Foster, D.J.; Kel’In, A.V.; Zlatev, I.; Bisbe, A.; Jayaraman, M.; Lackey, J.G.; Rajeev, K.G.; Charissé, K.; Harp, J.; et al. Chirality Dependent Potency Enhancement and Structural Impact of Glycol Nucleic Acid Modification on SiRNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8537–8546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraszti, R.A.; Roux, L.; Coles, A.H.; Turanov, A.A.; Alterman, J.F.; Echeverria, D.; Godinho, B.M.D.C.; Aronin, N.; Khvorova, A. 5’-Vinylphosphonate Improves Tissue Accumulation and Efficacy of Conjugated SiRNAs in Vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 7581–7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, R.; Willoughby, J.L.S.; Liu, J.; Foster, D.J.; Brigham, B.; Theile, C.S.; Charisse, K.; Akinc, A.; Guidry, E.; Pei, Y.; et al. 5′-(E)-Vinylphosphonate: A Stable Phosphate Mimic Can Improve the RNAi Activity of SiRNA-GalNAc Conjugates. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 985–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; van der Flier, W.M.; Jessen, F.; Hoozemanns, J.; Thal, D.R.; Boche, D.; Brosseron, F.; Teunissen, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Jacobs, A.H.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 25, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and Microglial Activation in Alzheimer Disease: Where Do We Go from Here? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trist, B.G.; Hilton, J.B.; Hare, D.J.; Crouch, P.J.; Double, K.L. Superoxide Dismutase 1 in Health and Disease: How a Frontline Antioxidant Becomes Neurotoxic. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 9215–9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, P.; Gagliardi, S.; Cova, E.; Cereda, C. SOD1 Transcriptional and Posttranscriptional Regulation and Its Potential Implications in ALS. Neurol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 458427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunton-Stasyshyn, R.K.A.; Saccon, R.A.; Fratta, P.; Fisher, E.M.C. SOD1 Function and Its Implications for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Pathology: New and Renascent Themes. Neuroscientist 2015, 21, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnylan Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Alnylam Reports Additional Positive Interim Phase 1 Results for ALN-APP, in Development for Alzheimer’s Disease and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Available online: https://investors.alnylam.com/press-release?id=27761 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Cohen, S.; Ducharme, S.; Brosch, J.R.; Vijverberg, E.G.B.; Apostolova, L.G.; Sostelly, A.; Goteti, S.; Makarova, N.; Avbersek, A.; Guo, W.; et al. Interim Phase 1 Part A Results for ALN-APP, the First Investigational RNAi Therapeutic in Development for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, e082650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Meglio, M. Overviewing Encouraging Early-Stage Data on Mivelsiran, RNA Therapeutic for Alzheimer Disease: Sharon Cohen, MD, FRCPC. NeurologyLive. 2024. Available online: https://www.neurologylive.com/view/overviewing-encouraging-early-stage-data-mivelsiran-rna-therapeutic-alzheimers-sharon-cohen (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cohen, S.; Ducharme, S.; Brosch, J.R. Single Ascending Dose Results from an Ongoing Phase 1 Study of Mivelsiran (ALN-APP), the First Investigational RNA Interference Therapeutic Targeting Amyloid Precursor Protein for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, e084521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Gaxiola, C.A.; Rosales-Leycegui, F.; Gaxiola-Rubio, A.; Moreno-Ortiz, J.M.; Figuera, L.E. Early- and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: Two Sides of the Same Coin? Diseases 2024, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, T.; Rogaeva, E.; Kurup, J.T.; Beecham, G.; Reitz, C. Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: What Is Missing in Research? Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2021, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirkis, D.W.; Bonham, L.W.; Johnson, T.P.; La Joie, R.; Yokoyama, J.S. Dissecting the Clinical Heterogeneity of Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2674–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, M.F. Early-Onset Alzheimer Disease and Its Variants. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2019, 25, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.C. Clinical Dementia Rating: A Reliable and Valid Diagnostic and Staging Measure for Dementia of the Alzheimer Type. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1997, 9, 173–176; discussion 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tombaugh, T.N.; McIntyre, N.J. The Mini-Mental State Examination: A Comprehensive Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1992, 40, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowsky, J.L.; Zheng, H. Practical Considerations for Choosing a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblak, A.L.; Lin, P.B.; Kotredes, K.P.; Pandey, R.S.; Garceau, D.; Williams, H.M.; Uyar, A.; O’Rourke, R.; O’Rourke, S.; Ingraham, C.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of the 5XFAD Mouse Model for Preclinical Testing Applications: A MODEL-AD Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 713726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyckaerts, C.; Potier, M.C.; Delatour, B. Alzheimer Disease Models and Human Neuropathology: Similarities and Differences. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 115, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.Z.; Peng, T.; Duarte, M.L.; Wang, M.; Cai, D. Updates on Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, J.; Ittner, L.M. Animal Models of Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, e00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, G.A.; Gama Sosa, M.A.; De Gasperi, R. Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2010, 77, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, E.L.; Figueiró, M.; Gattaz, W.F. Insights into Alzheimer Disease Pathogenesis from Studies in Transgenic Animal Models. Clinics 2011, 66, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Varo, R.; Mejias-Ortega, M.; Fernandez-Valenzuela, J.J.; Nuñez-Diaz, C.; Caceres-Palomo, L.; Vegas-Gomez, L.; Sanchez-Mejias, E.; Trujillo-Estrada, L.; Garcia-Leon, J.A.; Moreno-Gonzalez, I.; et al. Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Integrative Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacace, R.; Sleegers, K.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Molecular Genetics of Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Revisited. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016, 12, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Hasana, S.; Hossain, F.; Islam, S.; Behl, T.; Perveen, A.; Hafeez, A.; Ashraf, G.M. Molecular Genetics of Early- and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Gene Ther. 2020, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, C.A.; Wilson, J.G.; Everhart, A.; Wilcock, D.M.; Puoliväli, J.; Heikkinen, T.; Oksman, J.; Jääskeläinen, O.; Lehtimäki, K.; Laitinen, T.; et al. MNos2 Deletion and Human NOS2 Replacement in Alzheimer Disease Models. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 73, 752–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, D.M.; Lewis, M.R.; Van Nostrand, W.E.; Davis, J.; Previti, M.L.; Gharkholonarehe, N.; Vitek, M.P.; Colton, C.A. Progression of Amyloid Pathology to Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in an Amyloid Precursor Protein Transgenic Mouse Model by Removal of Nitric Oxide Synthase 2. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillie, D.; Cha, D.; Ferraro, G.; Bittner, K.; Sostelly, A.; Mooney, T.; Brown, K. Small Interfering RNA Targeting Amyloid-Beta Precursor Protein Reduces Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in 5xFAD Mice and Abrogates Behavior Changes in Early Intervention Paradigm. In Proceedings of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 27–31 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, H.; Cole, S.L.; Logan, S.; Maus, E.; Shao, P.; Craft, J.; Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.; Ohno, M.; Disterhoft, J.; Van Eldik, L.; et al. Intraneuronal β-Amyloid Aggregates, Neurodegeneration, and Neuron Loss in Transgenic Mice with Five Familial Alzheimer’s Disease Mutations: Potential Factors in Amyloid Plaque Formation. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10129–10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eimer, W.A.; Vassar, R. Neuron Loss in the 5XFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Correlates with Intraneuronal Aβ42 Accumulation and Caspase-3 Activation. Mol. Neurodegener. 2013, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pádua, M.S.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Lopes, P.A. Behaviour Hallmarks in Alzheimer’s Disease 5xFAD Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forner, S.; Kawauchi, S.; Balderrama-Gutierrez, G.; Kramár, E.A.; Matheos, D.P.; Phan, J.; Javonillo, D.I.; Tran, K.M.; Hingco, E.; da Cunha, C.; et al. Systematic Phenotyping and Characterization of the 5xFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmita, A.O.; Ong, E.C.; Nazarenko, T.; Mao, S.; Komarek, L.; Thalmann, M.; Hantakova, V.; Spieth, L.; Berghoff, S.A.; Barr, H.J.; et al. Parental Origin of Transgene Modulates Amyloid-β Plaque Burden in the 5xFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2025, 113, 838–846.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, S.; Chopin, P.; File, S.E.; Briley, M. Validation of Open:Closed Arm Entries in an Elevated plus-Maze as a Measure of Anxiety in the Rat. J. Neurosci. Methods 1985, 14, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walf, A.A.; Frye, C.A. The Use of the Elevated plus Maze as an Assay of Anxiety-Related Behavior in Rodents. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawhar, S.; Trawicka, A.; Jenneckens, C.; Bayer, T.A.; Wirths, O. Motor Deficits, Neuron Loss, and Reduced Anxiety Coinciding with Axonal Degeneration and Intraneuronal Aβ Aggregation in the 5XFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 196.e29–196.e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Baldauf, K.; Wetzel, W.; Reymann, K.G. Behavioral and EEG Changes in Male 5xFAD Mice. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 135, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhr, O.B.; Coelho, T.; Buades, J.; Pouget, J.; Conceicao, I.; Berk, J.; Schmidt, H.; Waddington-Cruz, M.; Campistol, J.M.; Bettencourt, B.R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Patisiran for Familial Amyloidotic Polyneuropathy: A Phase II Multi-Dose Study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Verena, K. Phase 1 Study of ALN-TTRsc02, a Subcutaneously Administered Investigational RNAi Therapeutic for the Treatment of Transthyretin-Mediated Amyloidosis. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 175, S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardh, E.; Harper, P.; Balwani, M.; Stein, P.; Rees, D.; Bissell, D.M.; Desnick, R.; Parker, C.; Phillips, J.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; et al. Phase 1 Trial of an RNA Interference Therapy for Acute Intermittent Porphyria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| siRNA Modification | Delivery Mechanism | Target Organ/Cells | Administration Route | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNPs | Encapsulated in ionizable lipid nanoparticles, coated with ApoE for hepatocyte targeting via ApoE receptors | Liver/hepatocytes | IV |

|

|

| GalNAc Conjugation | N-acetylgalactosamine bind to ASGPR on hepatocytes | Liver/hepatocytes | SC |

|

|

| C16 Conjugation (2′-O-Hexadecyl-siRNA) | C16 fatty acid chain enhances lipophilicity and membrane interactions | CNS/neurons, astrocytes, microglia; or ocular and pulmonary tissues) | IT or ICV |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Titze-de-Almeida, R.; Oliveira Gomes, G.d.M.; Santos, T.C.d.; Titze-de-Almeida, S.S. C16-siRNAs in Focus: Development of ALN-APP, a Promising RNAi-Based Therapeutic for Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010026

Titze-de-Almeida R, Oliveira Gomes GdM, Santos TCd, Titze-de-Almeida SS. C16-siRNAs in Focus: Development of ALN-APP, a Promising RNAi-Based Therapeutic for Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleTitze-de-Almeida, Ricardo, Guilherme de Melo Oliveira Gomes, Tayná Cristina dos Santos, and Simoneide Souza Titze-de-Almeida. 2026. "C16-siRNAs in Focus: Development of ALN-APP, a Promising RNAi-Based Therapeutic for Alzheimer’s Disease" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010026

APA StyleTitze-de-Almeida, R., Oliveira Gomes, G. d. M., Santos, T. C. d., & Titze-de-Almeida, S. S. (2026). C16-siRNAs in Focus: Development of ALN-APP, a Promising RNAi-Based Therapeutic for Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010026