Effects of Lycopene Supplementation on Bone Tissue: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

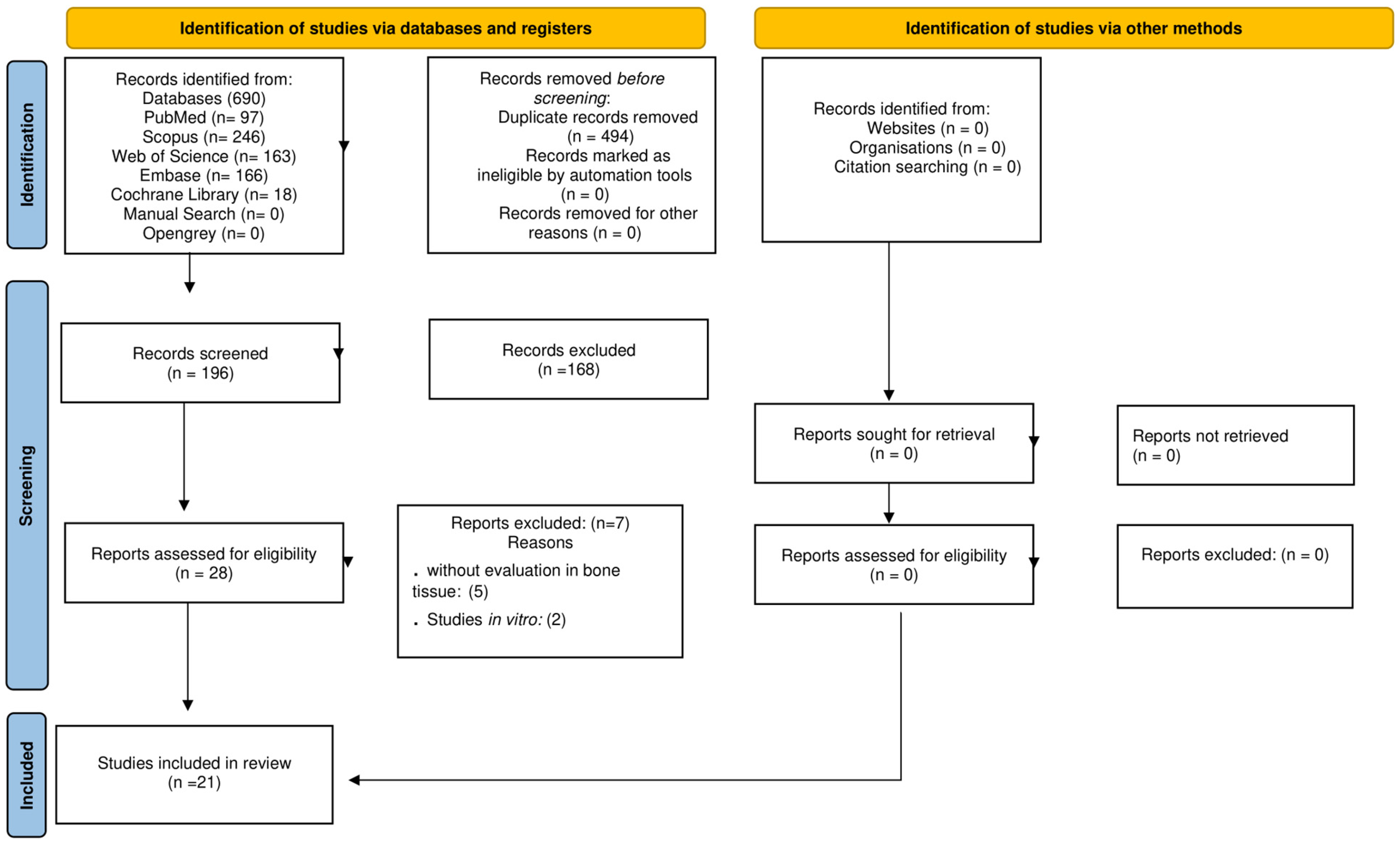

2.1. Study Selection

2.2. Characteristics of Studies

2.2.1. Clinical Trials

2.2.2. Preclinical Models

2.3. Outcomes Related to LYC Supplementation

2.3.1. Clinical Trials

2.3.2. Preclinical Studies

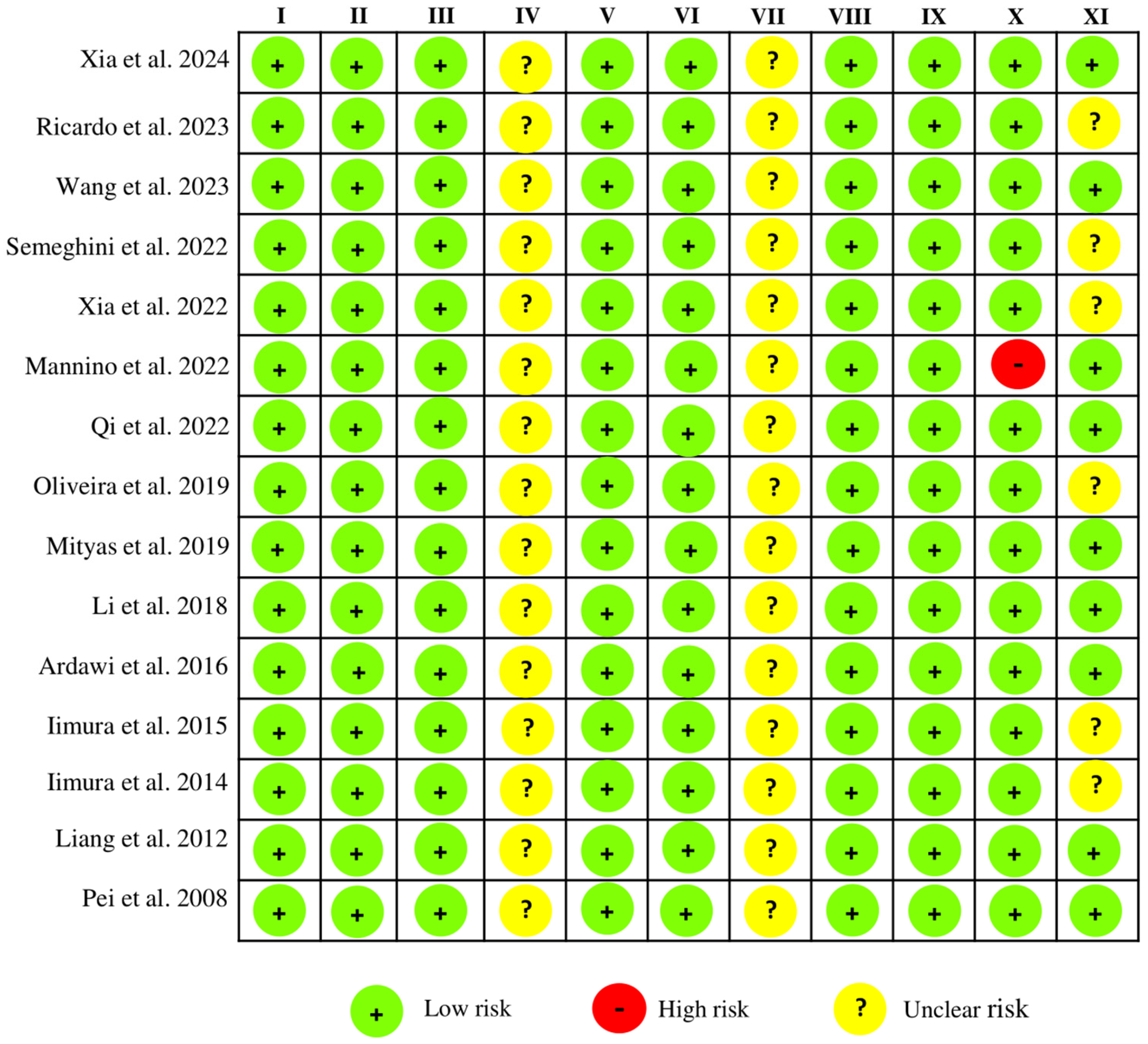

2.4. Risk of Bias Within Studies

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Protocol and Registration

4.2. PICO Question and Search Strategy

- Population (P): Adult patients (aged ≥20 years), with no restrictions on gender or profession, or animal models.

- Intervention (I): Lycopene supplementation.

- Comparison (C): Placebo or another control.

- Outcome (O): The primary outcome was bone mineral density (BMD) due to its clinical relevance as a standard indicator of bone strength and predictor of fracture risk. Secondary outcomes included bone turnover markers (e.g., osteocalcin, alkaline phosphatase, and CTX), bone microarchitecture assessed by microtomographic or histomorphometric analyses, and fracture incidence or other surrogate endpoints indicative of bone health.

4.3. Eligibility Criteria

4.4. Selection of Studies and Data Collection

4.5. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Strategy |

|---|

| PUBMED/MEDLINE ((((((((Bone[MeSH Terms]) OR ((Bone) OR (Bones and Bone Tissue) OR (Bones and Bone) OR (Bone and Bone) OR(Bone Tissue) OR (Bone Tissues) OR (Tissue, Bone) OR (Tissues, Bone) OR (Bony Apophyses) OR (Apophyses, Bony) OR (Bony Apophysis) OR (Apophysis, Bony) OR (Condyle) OR (Condyles) OR (Bones))) OR ((Bone Remodeling)[MeSH Terms])) OR ((Bone Remodeling) OR (Remodeling, Bone) OR (Bone Turnover) OR (Bone Turnovers) OR (Turnover, Bone) OR (Turnovers, Bone))) OR ((Osteogenesis)[MeSH Terms])) OR ((Osteogenesis) OR (Bone Formation) OR (Ossification) OR (Ossifications) OR (Osteoclastogenesis) OR (Osteoclastogeneses) OR (Endochondral Ossification) OR (Endochondral Ossifications) OR(Ossification, Endochondral) OR (Ossifications, Endochondral) OR (Physiologic Ossification) OR (Ossification, Physiological) OR (Physiological Ossification) OR (Ossification, Physiologic))) OR ((Bone Resorption)[MeSH Terms])) OR ((Bone Resorption) OR (Bone Resorptions) OR (Resorption, Bone) OR (Resorptions, Bone) OR (Osteoclastic Bone Loss) OR (Bone Loss, Osteoclastic) OR (Bone Losses, Osteoclastic) OR (Loss, Osteoclastic Bone) OR (Losses, Osteoclastic Bone) OR (Osteoclastic Bone Losses))) AND (((Lycopene[MeSH Terms])) OR ((Lycopene) OR (LYC-O-MATO) OR (LYC O MATO) OR (LYCOMATO) OR (All-trans-Lycopene) OR (All trans Lycopene) OR (Lycopene, (7-cis,7′-cis,9-cis,9′-cis)-isomer -) OR (Pro-Lycopene) OR (Pro Lycopene) OR (Prolycopene) OR (Lycopene, (cis)-isomer) OR (Lycopene, (13-cis)-isomer))) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed (accessed on 8 May 2025)) |

| SCOPUS (TITLE-ABS-KEY ((lycopene) OR (lyc-o-mato) OR (lyc AND o AND mato) OR (lycomato) OR (all-trans-lycopene) OR (all AND trans AND lycopene) OR (lycopene) OR (pro-lycopene) OR (pro AND lycopene)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((bone) OR (bones AND bone AND tissue) OR (bones AND bone) OR (bone AND bone) OR (bone AND tissue) OR (bone AND tissues) OR (tissue, AND bone) OR (tissues, AND bone) OR (bony AND apophyses) OR (apophyses, AND bony) OR (bony AND apophysis) OR (apophysis, AND bony) OR (condyle) OR (condyles) OR (bones) OR (bone) OR (bone AND remodeling) OR (remodeling, AND bone) OR (bone AND turnover) OR (bone AND turnovers) OR (turnover, AND bone) OR (turnovers, AND bone) OR (bone AND formation) OR (bone AND formation) OR (ossification) OR (ossifications) OR (osteoclastogenesis) OR (osteoclastogeneses) OR (endochondral AND ossification) OR (endochondral AND ossifications) OR (ossification, AND endochondral) OR (ossifications, AND endochondral) OR (physiologic AND ossification) OR (ossification, AND physiological) OR (physiological AND ossification) OR (ossification, AND physiologic) OR (bone AND resorption) OR (bone AND resorptions) OR (resorption, AND bone) OR (resorptions, AND bone) OR (osteoclastic AND bone AND loss) OR (bone AND loss, AND osteoclastic) OR (bone AND losses, AND osteoclastic) OR (loss, AND osteoclastic AND bone) OR (losses, AND osteoclastic AND bone) OR (osteoclastic AND bone AND losses))) (http://www.scopus.com (accessed on 8 May 2025)) |

| EMBASE (‘lyc o mato’/exp OR ‘lyc o mato’ OR (lyc AND o AND (‘mato’/exp OR mato)) OR lycomato OR ‘all trans lycopene’ OR (all AND trans AND (‘lycopene’/exp OR lycopene)) OR ‘lycopene’/exp OR lycopene OR ‘pro lycopene’ OR (pro AND (‘lycopene’/exp OR lycopene))) AND (bones:ti,ab,kw AND ‘bone tissue’:ti,ab,kw OR (bones:ti,ab,kw AND bone:ti,ab,kw) OR ‘bone tissue’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone tissues’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘tissue, bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘tissues, bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bony apophyses’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘apophyses, bony’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bony apophysis’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘apophysis, bony’:ti,ab,kw OR condyle:ti,ab,kw OR condyles:ti,ab,kw OR bones:ti,ab,kw OR bone:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone remodeling’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘remodeling, bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone turnover’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone turnovers’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘turnover, bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘turnovers, bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone formation’:ti,ab,kw OR ossification:ti,ab,kw OR ossifications:ti,ab,kw OR osteoclastogenesis:ti,ab,kw OR osteoclastogeneses:ti,ab,kw OR ‘endochondral ossification’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘endochondral ossifications’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘ossification, endochondral’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘ossifications, endochondral’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physiologic ossification’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘ossification, physiological’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physiological ossification’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘ossification, physiologic’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone resorption’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone resorptions’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘resorption, bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘resorptions, bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘osteoclastic bone loss’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone loss, osteoclastic’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘bone losses, osteoclastic’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘loss, osteoclastic bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘losses, osteoclastic bone’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘osteoclastic bone losses’:ti,ab,kw) AND [embase]/lim (https://www.embase.com (accessed on 8 May 2025)) |

| WEB OF SCIENCE ((((((((Bone) OR ((Bone) OR (Bones and Bone Tissue) OR (Bones and Bone) OR (Bone and Bone) OR(Bone Tissue) OR (Bone Tissues) OR (Tissue, Bone) OR (Tissues, Bone) OR (Bony Apophyses) OR (Apophyses, Bony) OR (Bony Apophysis) OR (Apophysis, Bony) OR (Condyle) OR (Condyles) OR (Bones))) OR ((Bone Remodeling) OR ((Bone Remodeling) OR (Remodeling, Bone) OR (Bone Turnover) OR (Bone Turnovers) OR (Turnover, Bone) OR (Turnovers, Bone))) OR ((Osteogenesis) OR ((Osteogenesis) OR (Bone Formation) OR (Ossification) OR (Ossifications) OR (Osteoclastogenesis) OR (Osteoclastogeneses) OR (Endochondral Ossification) OR (Endochondral Ossifications) OR(Ossification, Endochondral) OR (Ossifications, Endochondral) OR (Physiologic Ossification) OR (Ossification, Physiological) OR (Physiological Ossification) OR (Ossification, Physiologic))) OR ((Bone Resorption) OR ((Bone Resorption) OR (Bone Resorptions) OR (Resorption, Bone) OR (Resorptions, Bone) OR (Osteoclastic Bone Loss) OR (Bone Loss, Osteoclastic) OR (Bone Losses, Osteoclastic) OR (Loss, Osteoclastic Bone) OR (Losses, Osteoclastic Bone) OR (Osteoclastic Bone Losses))) AND (((Lycopene) OR ((Lycopene) OR (LYC-O-MATO) OR (LYC O MATO) OR (LYCOMATO) OR (All-trans-Lycopene) OR (All trans Lycopene) OR (Lycopene, (7-cis,7′-cis,9-cis,9′-cis)-isomer -) OR (Pro-Lycopene) OR (Pro Lycopene) OR (Prolycopene) OR (Lycopene, (cis)-isomer) OR (Lycopene, (13-cis)-isomer))) (https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science-core-collection (accessed on 8 May 2025)) |

| COCHRANE LIBRARY (Bone) OR (Bone) OR (Bones and Bone Tissue) OR (Bones and Bone) OR (Bone and Bone) OR (Bone Tissue) OR (Bone Tissues) OR (Tissue, Bone) OR (Tissues, Bone) OR (Bony Apophyses) OR (Apophyses, Bony) OR (Bony Apophysis) OR (Apophysis, Bony) OR (Condyle) OR (Condyles) OR (Bones) OR (Bone Remodeling) OR (Bone Remodeling) OR (Remodeling, Bone) OR (Bone Turnover) OR (Bone Turnovers) OR (Turnover, Bone) OR (Turnovers, Bone) OR (Osteogenesis) OR (Osteogenesis) OR (Bone Formation) OR (Ossification) OR (Ossifications) OR (Osteoclastogenesis) OR (Osteoclastogeneses) OR (Endochondral Ossification) OR (Endochondral Ossifications) OR(Ossification, Endochondral) OR (Ossifications, Endochondral) OR (Physiologic Ossification) OR (Ossification, Physiological) OR (Physiological Ossification) OR (Ossification, Physiologic) OR (Bone Resorption) OR (Bone Resorption) OR (Bone Resorptions) OR (Resorption, Bone) OR (Resorptions, Bone) OR (Osteoclastic Bone Loss) OR (Bone Loss, Osteoclastic) OR (Bone Losses, Osteoclastic) OR (Loss, Osteoclastic Bone) OR (Losses, Osteoclastic Bone) OR (Osteoclastic Bone Losses) in Title Abstract Keyword AND (Lycopene) OR (Lycopene) OR (LYC-O-MATO) OR (LYC O MATO) OR (LYCOMATO) OR (All-trans-Lycopene) OR (All trans Lycopene) OR (Lycopene, (7-cis,7′-cis,9-cis,9′-cis)-isomer -) OR (Pro-Lycopene) OR (Pro Lycopene) OR (Prolycopene) OR (Lycopene, (cis)-isomer) OR (Lycopene, (13-cis)-isomer) (Lycopene) OR (LYC-O-MATO) OR (LYC O MATO) OR (LYCOMATO) OR (All-trans-Lycopene) OR (All trans Lycopene) in Title Abstract Keyword (https://www.cochranelibrary.com (accessed on 8 May 2025)) |

References

- Weivoda, M.M.; Bradley, E.W. Macrophages and bone remodeling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2023, 38, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florencio-Silva, R.; Sasso, G.R.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Simões, M.J.; Cerri, P.S. Biology of bone tissue: Structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. BioMed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 421746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marie, P.J.; Kassem, M. Osteoblasts in osteoporosis: Past, emerging, and future anabolic targets. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 165, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Ortega, R.F.; Ortega-Meléndez, A.I.; Patiño, N.; Rivera-Paredez, B.; Hidalgo-Bravo, A.; Velázquez-Cruz, R. The involvement of microRNAs in bone remodeling signaling pathways and their role in the development of osteoporosis. Biology 2024, 13, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; McDonald, J.M. Bone resorption and formation: Mechanisms and implications. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- LeBoff, M.S.; Greenspan, S.L.; Insogna, K.L.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Saag, K.G.; Singer, A.J.; Siris, E.S. The clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2022, 33, 2049–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, E.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Mobasseri, M.; Shakouri, S.K.; Mikaeli, P.; Farshbaf-Khalili, A. Prevalence of primary osteoporosis and low bone mass in postmenopausal women and related risk factors. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anish, R.J.; Nair, A. Osteoporosis management—Current and future perspectives: A systematic review. J. Orthop. 2024, 53, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragonzoni, L.; Barone, G.; Benvenuti, F.; Ripamonti, C.; Lisi, L.; Benedetti, M.G.; Marini, S.; Dallolio, L.; Latessa, M.P.; Zinno, R.; et al. Influence of coaching on effectiveness, participation, and safety of an exercise program for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: A randomized trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2023, 18, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancia, S.; Högler, W.; Sakkers, R.J.B.; Appelman-Dijkstra, N.M.; Boot, A.M.; Sas, T.C.J.; Renes, J.S. Osteoporosis in children and adolescents: How to treat and monitor? Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Ferro, Y.; Maurotti, S.; Salvati, M.A.; Mazza, E.; Pujia, R.; Terracciano, R.; Maggisano, G.; Mare, R.; Giannini, S.; et al. Lycopene and bone: An in vitro investigation and a pilot prospective clinical study. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukon, Y.; Makino, T.; Kodama, J.; Tsukazaki, H.; Tateiwa, D.; Yoshikawa, H.; Kaito, T. Molecular-based treatment strategies for osteoporosis: A literature review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Song, J.; Kong, L.; Yuan, T.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Hou, B.; Lu, Y.; Du, G. The strategies and techniques of drug discovery from natural products. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 216, 107686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, G.; Domazetovic, V.; Nediani, C.; Ruzzolini, J.; Favre, C.; Brandi, M.L. Oxidative stress and natural antioxidants in osteoporosis: Novel preventive and therapeutic approaches. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques-Carvalho, A.; Kim, H.N.; Almeida, M. The role of reactive oxygen species in bone cell physiology and pathophysiology. Bone Rep. 2023, 19, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domazetovic, V.; Marcucci, G.; Iantomasi, T.; Brandi, M.L.; Vincenzini, M.T. Oxidative stress in bone remodeling: Role of antioxidants. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 2017, 14, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardawi, M.M.; Badawoud, M.H.; Hassan, S.M.; Rouzi, A.A.; Ardawi, J.M.S.; AlNosanim, N.M.; Qari, M.H.; Mousa, S.A. Lycopene treatment against loss of bone mass, microarchitecture and strength in relation to regulatory mechanisms in a postmenopausal osteoporosis model. Bone 2016, 83, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iimura, Y.; Agata, U.; Takeda, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Ezawa, I.; Omi, N. The protective effect of lycopene intake on bone loss in ovariectomized rats. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2015, 33, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.V.; Rao, L.G. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 55, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla-González, V.; Rojas-Solé, C.; Gómez-Hevia, F.; González-Fernández, T.; Cereceda-Cornejo, A.; Chichiarelli, S.; Saso, L.; Rodrigo, R. Tapping into nature’s arsenal: Harnessing the potential of natural antioxidants for human health and disease prevention. Foods 2024, 13, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.M.; Sevindik, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Nami, M.; Ozdemir, B.; Kaplan, D.N.; Selamoglu, Z.; Hasan, M.; Kumar, M.; Alshehri, M.M.; et al. Lycopene: Food Sources, Biological Activities, and Human Health Benefits. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 2713511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali, A.; Fathzadeh, K.; Askari, G.; Sadeghi, O. Dietary intake of tomato and lycopene, blood levels of lycopene, and risk of total and specific cancers in adults: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1516048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapała, A.; Szlendak, M.; Motacka, E. The anti-cancer activity of lycopene: A systematic review of human and animal studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.; Behmanesh Nia, F.; Ghaedi, K.; Mohammadpour, S.; Amirani, N.; Goudarzi, K.; Kolbadi, K.S.H.; Ghanavati, M.; Ashtary-Larky, D. The effects of lycopene and tomato consumption on cardiovascular risk factors in adults: A GRADE assessment systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 1671–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abir, M.H.; Mahamud, A.G.M.S.U.; Tonny, S.H.; Anu, M.S.; Hossain, K.H.S.; Protic, I.A.; Khan, M.S.U.; Baroi, A.; Moni, A.; Uddin, M.J. Pharmacological potentials of lycopene against aging and aging-related disorders: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5701–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Chen, B.; Bai, Y.; Miao, T.; Rui, L.; Zhang, H.; Xia, B.; Li, Y.; Gao, S.; Wang, X.D.; et al. Lycopene in protection against obesity and diabetes: A mechanistic review. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159, 104966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafe, M.O.; Gumede, N.M.; Nyakudya, T.T.; Chivandi, E. Lycopene: A potent antioxidant with multiple health benefits. J. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 2024, 6252426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Dai, X.; Shi, H.; Yin, J.; Xu, T.; Liu, T.; Yue, G.; Guo, H.; Liang, R.; Liu, Y.; et al. Lycopene promotes osteogenesis and reduces adipogenesis through regulating FoxO1/PPARγ signaling in ovariectomized rats and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Dai, X.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, D.; Mo, F.; Gao, S.; et al. Lycopene improves bone quality and regulates AGE/RAGE/NF-κB signaling pathway in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 3697067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeghini, M.S.; Scalize, P.H.; Coelho, M.C.; Fernandes, R.R.; Pitol, D.L.; Tavares, M.S.; de Sousa, L.G.; Coppi, A.A.; Siessere, S.; Bombonato-Prado, K.F. Lycopene prevents bone loss in ovariectomized rats and increases the number of osteocytes and osteoblasts. J. Anat. 2022, 241, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Rodrigues, J.; Fernandes, M.H.; Pinho, O.; Monteiro, P.R.R. Modulation of human osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis by lycopene. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 57, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, G.R.; Vargas-Sanchez, P.K.; Fernandes, R.R.; Ricoldi, M.S.T.; Semeghini, M.S.; Pitol, D.L.; de Sousa, L.G.; Siessere, S.; Bombonato-Prado, K.F. Lycopene influences osteoblast functional activity and prevents femur bone loss in female rats submitted to an experimental model of osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2019, 37, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeta, M.; Sharma, S.; Unni, J.; Khandelwal, S.; Choranur, A.; Malik, S. Cardiovascular and osteoporosis protection at menopause with lycopene: A placebo-controlled double-blind randomized clinical trial. J. Mid-Life Health 2022, 13, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackinnon, E.S.; Rao, A.V.; Rao, L.G. Dietary restriction of lycopene for a period of one month resulted in significantly increased biomarkers of oxidative stress and bone resorption in postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2011, 15, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, E.S.; Rao, A.V.; Josse, R.G.; Rao, L.G. Supplementation with the antioxidant lycopene significantly decreases oxidative stress parameters and the bone resorption marker N-telopeptide of type I collagen in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, E.S.; El-Sohemy, A.; Rao, A.V.; Rao, L.G. Paraoxonase 1 polymorphisms 172T→A and 584A→G modify the association between serum concentrations of the antioxidant lycopene and bone turnover markers and oxidative stress parameters in women 25–70 years of age. J. Nutr. Nutr. 2010, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.G.; MacKinnon, E.S.; Josse, R.G.; Murray, T.M.; Strauss, A.; Rao, A.V. Lycopene consumption decreases oxidative stress and bone resorption markers in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 2007, 18, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Heng, K.; Song, X.; Zhai, J.; Zhang, H.; Geng, Q. Lycopene improves bone quality in SAMP6 mice by inhibiting oxidative stress, cellular senescence, and the SASP. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, e2300330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, V.; Sousa, L.G.; Regalo, I.H.; Pitol, D.L.; Bombonato-Prado, K.F.; Regalo, S.C.H.; Siessere, S. Lycopene enhances bone neoformation in calvaria bone defects of ovariectomized rats. Braz. Dent. J. 2023, 34, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, F.; D’Angelo, T.; Pallio, G.; Ieni, A.; Pirrotta, I.; Giorgi, D.A.; Scarfone, A.; Mazziotti, S.; Booz, C.; Bitto, A.; et al. The nutraceutical genistein-lycopene combination improves bone damage induced by glucocorticoids by stimulating the osteoblast formation process. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.S.; Shao, M.L.; Sun, Z.; Chen, S.M.; Hu, Y.J.; Wang, H.T.; Wei, T.K.; Li, X.S.; Zheng, H.X. Lycopene ameliorates diabetic osteoporosis via anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidation, and increasing osteoprotegerin/RANKL expression ratio. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 83, 104539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mityas, G.S.; Tawfik, S.M.; Salah, E.F. Histological study of the possible protective effect of lycopene on glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in adult male albino rat. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2019, 87, 2121–2134. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xue, W.; Cao, Y.; Long, Y.; Xie, M. Effect of lycopene on titanium implant osseointegration in ovariectomized rats. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2018, 13, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iimura, Y.; Agata, U.; Takeda, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Ezawa, I.; Omi, N. Lycopene intake facilitates the increase of bone mineral density in growing female rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2014, 60, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Yu, F.; Tong, Z.; Zeng, W. Lycopene effects on serum mineral elements and bone strength in rats. Molecules 2012, 17, 7093–7102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, L.P.; Hui, B.D.; Wei, J.H. Antagonistil effect of lycopene on osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats. Chin. J. Public Health 2008, 24, 1107–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Faienza, M.F.; Giardinelli, S.; Annicchiarico, A.; Chiarito, M.; Barile, B.; Corbo, F.; Brunetti, G. Nutraceuticals and functional foods: A comprehensive review of their role in bone health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walallawita, U.S.; Wolber, F.M.; Ziv-Gal, A.; Kruger, M.C.; Heyes, J.A. Potential role of lycopene in the prevention of postmenopausal bone loss: Evidence from molecular to clinical studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobeiha, M.; Moghadasian, M.H.; Amin, N.; Jafarnejad, S. RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway: A mechanism involved in exercise-induced bone remodeling. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 6910312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.J.; Sims, N.A. RANKL/OPG; critical role in bone physiology. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2015, 16, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Mine, T.; Ogasa, H.; Taguchi, T.; Liang, C.T. Expression of RANKL/OPG during bone remodeling in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 411, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drakou, A.; Kaspiris, A.; Vasiliadis, E.; Evangelopoulos, D.S.; Koulalis, D.; Lenti, A.; Chatziioannou, S.; Pneumatikos, S.G. Oxidative stress and bone remodeling: An updated review. Ann. Case Rep. 2025, 10, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueni, G.; Scalzone, A.; Licini, C.; Gentile, P.; Mattioli-Belmonte, M. Insights into oxidative stress in bone tissue and novel challenges for biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 130, 112433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iantomasi, T.; Romagnoli, C.; Palmini, G.; Donati, S.; Falsetti, I.; Miglietta, F.; Aurilia, C.; Marini, F.; Giusti, F.; Brandi, M.L. Oxidative stress and inflammation in osteoporosis: Molecular mechanisms involved and the relationship with microRNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, G.; de Andrade Rodrigues, L.; Souza da Silva, A.A.; Gouvea, L.C.; Silva, R.C.L.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Cerri, P.S. Reduction of osteoclast formation and survival following suppression of cytokines by diacerein in periodontitis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 117086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaköy, Z.; Cadirci, E.; Dincer, B. A new target in inflammatory diseases: Lycopene. Eurasian. J. Med. 2022, 54 (Suppl. S1), 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zou, Q.; Suo, Y.; Tan, X.; Yuan, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Lycopene ameliorates systemic inflammation-induced synaptic dysfunction via improving insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver-brain axis. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 2125–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengi, V.U.; Saygun, I.; Bal, V.; Ozcan, E.; Ozkan, C.K.; Torun, D.; Avcu, F.; Kantarcı, A. Effect of antioxidant lycopene on human osteoblasts. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardawi, M.S.M.; Badawoud, M.H.; Hassan, S.M.; Ardawi, A.M.S.; Rouzi, A.A.; Qari, M.H.; Mousa, S.A. Lycopene nanoparticles promotes osteoblastogenesis and inhibits adipogenesis of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 6894–6907. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q.; Yu, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Guo, J.; Song, L. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts regulates global energy metabolism. Bone 2017, 97, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, B.F.; Xing, L. Biology of RANK, RANKL, and osteoprotegerin. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2007, 9 (Suppl. S1), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.J.; Strock, N.; Williams, N.; Lee, H.; Koltun, K.; Rogers, C.; Ferruzzi, M.; Nakatsu, C.; Weaver, C. Low dose daily prunes preserve hip bone mineral density with no impact on body composition in a 12-month randomized controlled trial in postmenopausal women: The prune study. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6 (Suppl. S1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, S.; Hannan, M.T.; Blumberg, J.; Cupples, L.A.; Kiel, D.P.; Tucker, K.L. Inverse association of carotenoid intakes with 4-y change in bone mineral density in elderly men and women: The Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arballo, J.; Amengual, J.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. Lycopene: A critical review of digestion, absorption, metabolism, and excretion. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cámara, M.; Sánchez-Mata, M.C.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, R.M.; Manzoor, S.; Caceres, J.O. Chapter 11-Lycopene: A Review of Chemical and Biological Activity Related to Beneficial Health Effects. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Rahman, A.-u., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 40, pp. 383–426. [Google Scholar]

- Devaraj, S.; Mathur, S.; Basu, A.; Aung, H.H.; Vasu, V.T.; Meyers, S.; Jialal, I. A dose-response study on the effects of purified lycopene supplementation on biomarkers of oxidative stress. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2008, 27, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voulgaridou, G.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Detopoulou, P.; Tsoumana, D.; Giaginis, C.; Kondyli, F.S.; Lymperaki, E.; Pritsa, A. Vitamin D and calcium in osteoporosis, and the role of bone turnover markers: A narrative review of recent data from RCTs. Diseases 2023, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, N.; Levy, R. The synergistic anti-inflammatory effects of lycopene, lutein, β-carotene, and carnosic acid combinations via redox-based inhibition of NF-κB signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wu, X.; Zhuang, W.; Xia, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Rao, Z.; Du, L.; Zhao, R.; Yi, M.; et al. Tomato and lycopene and multiple health outcomes: Umbrella review. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.B.; Vuong, L.T.; Ruckle, J.; Synal, H.A.; Schulze-König, T.; Wertz, K.; Rümbeli, R.; Liberman, R.G.; Skipper, P.L.; Tannenbaum, S.R.; et al. Lycopene bioavailability and metabolism in humans: An accelerator mass spectrometry study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustin, D.M.; Rodvold, K.A.; Sosman, J.A.; Diwadkar-Navsariwala, V.; Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis, M.; Viana, M.; Crowell, J.A.; Murray, J.; Tiller, P.; Bowen, P.E. Single-dose pharmacokinetic study of lycopene delivered in a well-defined food-based lycopene delivery system (tomato paste-oil mixture) in healthy adult male subjects. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, N.E.; Erdman, J.W., Jr.; Clinton, S.K. Complex interactions between dietary and genetic factors impact lycopene metabolism and distribution. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 539, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar]

- Embleton, N.; Wood, C.L. Growth, bone health, and later outcomes in infants born preterm. J. Pediatr. 2014, 90, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wood, C.L.; Wood, A.M.; Harker, C.; Embleton, N.D. Bone mineral density and osteoporosis after preterm birth: The role of early life factors and nutrition. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 902513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.P.; Nunes, G.P.; Ferrisse, T.M.; Strazzi-Sahyon, H.B.; Dezan-Júnior, E.; Cintra, L.T.A.; Sivieri-Araujo, G. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of phototherapy on postoperative pain in conventional endodontic reintervention. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalub, L.O.; Nunes, G.P.; Strazzi-Sahyon, H.B.; Ferrisse, T.M.; Dos Santos, P.H.; Gomes-Filho, J.E.; Cintra, L.T.A.; Sivieri-Araujo, G. Antimicrobial effectiveness of ultrasonic irrigation in root canal treatment: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 1343–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; version 6.5 (updated August 2024); Cochrane: London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://www.cochrane.org/authors/handbooks-and-manuals/handbook (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2011. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 12 January 2025).

| Author, Year (Location) | Study Design | Groups Number of Subjects (n); Mean Age | Characteristics of the Samples Included | Administration Protocol Lycopene | Assessment Method | Outcomes: Results | Intervention Effect | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meeta et al., 2022 [33] (India) | Multi-centric placebo-controlled double-blind randomized clinical trial | G1: Lyc; n = 60 G2: Placebo/n = 48 108 postmenopausal women (mean age—49.8 years) | Healthy postmenopausal women | LycoRed with a dosage of two capsules of 2 mg each was given twice daily after meals, 8 mg/day | ELISA; CLIA-COB S 411; liquid chromatography | Bone markers (ng/mL) Baseline/6 months G1: 0.5 ± 0.28/−0.13 ± 0.7 G2: 0.3 ± 0.07/−0.04 ± 0.1 P1NP (ng/mL) Baseline/6 months G1: 70.3 ± 11.45/−9.70 ± 25.0 G2: 50.5 ± 6.92/−2.96 ± 10.2 | Positive | This study highlights the potential of lycopene supplementation in supporting cardiac and bone health. |

| Russo et al., 2020 [11] (Italy) | Clinical study | G1: (lycopene) n = 39 G2: (control) n = 39 The mean age of the enrolled population was 63 ± 7 years. | Postmenopausal women | Lycopene-rich tomato sauce daily, from tomatoes ripened on-the-vine at a dose of 150 mg/day | Real-time PCR; chemiluminescent immunoassay on COBAS 8000; immunoassay on Liaison® XL; high-performance liquid chromatography. | G1/G2 BMD (g/cm2) Baseline: 0.39 ± 0.07; 0.41 ± 0.1 12 Weeks: 0.39 ± 0.08/0.38 ± 0.08 Bone alkaline phosphatase (ug/L) Baseline: 18.1 ± 7.0/19.2 ± 6.9 12 weeks: 14.6 ± 5.9/17.2 ± 6.7 | Positive | Daily consumption of 150 mg of lycopene-rich tomato sauce for three months prevented bone loss in postmenopausal women. |

| Mackinnon et al., 2011 [34] (Canada) | Clinical study | G1: lycopene; 23 healthy postmenopausal women age (years) 54.4 ± 0.6 | Postmenopausal women | Participants were given a list of lycopene-containing foods to avoid for the remainder of the study. Another set of dietary records and a fasting blood sample were collected following a one-month washout period. | High-performance liquid chromatography, Trolox-equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay, ELISA | Lycopene restriction: one month Protein thiol: decreased from 423.7 mM ± 19.31 to 392.3 mM ± 14.22 TBARS: increase from 8.1 nmol/mL ± 0.4 to 9.18 nmol/mL ± 0.76; Protein oxidation: high 5.5% ± 3.3 Lipid peroxidation: high 14.5% ± 7.1; Endogenous antioxidant enzymes; CAT decrease was 8.4% ± 9.3; and SOD 22.7% ± 11.8 Bone resorption marker: NTx increase of 20.6% ± 9.8. | Positive | Lycopene-rich products in the daily diet may help maintain overall health and reduce the risk of age-related chronic diseases, especially osteoporosis. |

| Mackinnon et al., 2011 [35] (Canada) | Randomized controlled trial | G1.1: 15 mg lycopene tomato juice (30 mg/day), n = 15; age 55.2 ± 0.8; G1.2: 35 mg in the form of lycopene-rich tomato juice (70 mg/day). n = 15. Age 56.1 ± 0.64; G1.3: 15 mg lycopene in the form of tomato lycopene capsules (30 mg/day), n = 15, age: 54.3 ± 0.7; G2: placebo, n = 15, age: 55.1 | Postmenopausal women | Following a 1-month washout without lycopene consumption, participants consumed either treatment (n = 15/group) twice daily for total lycopene intakes of 30, 70, 30, and 0 mg/day, respectively, for 4 months. | High-performance liquid chromatography, Trolox-equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay, ELISA | Bone turnover markers BAP (U/L) G1.1: 22.3 ± 2.3; G1.2: 25.1 ± 1.98 G1.3: 23.1 ± 1.59; G2: 24.03 ± 2.36 Bone turnover markers-NTx (nM BCE): G1.1: 25.3 ± 2.16; G1.2: 22.64 ± 1.70; G1.3: 24.65 ± 2.12; G2: 20.25 ± 1.76 | Positive | Lycopene intervention, given in capsule or juice form, supplying at least 30 mg/day, may decrease the risk of osteoporosis by decreasing oxidative stress and bone resorption. |

| Mackinnon et al., 2010 [36] (Canada) | Clinical study | 107 female participants 25–70 years; genotypes 172T-A, 5 84A-G Age in years: 49.50 | Blood samples | Using the USDA National Nutrient Database as a reference, lycopene content was calculated in milligrams for each food item, and the average daily intake was determined for each participant. | Blood genomic DNA isolation Kit; high-performance liquid chromatography; antioxidant capacity assay; ELISA | Genotype 172T→A NTx (nM BCE): TT 20.48 ± 0.9; TA 21.5 ± 1.3; AA 19.9 ± 2.1 TBARS (nmol/mL): TT 7.6 ± 0.4; TA 7.9 ± 0.4; AA 6.9 ± 0.5 BAP (U/L): TT 20.6 ± 1.2; TA 22.9 ± 1.1; AA 29.03 ± 2.4 Genotype 584A→G NTx, nM BCE: AA 20.9 ± 1.0; AG 21.39 ± 1.30; GG 17.78 ± 2.50 TBARS, nmol/mL: AA 7.93 ± 0.40; AG 7.36 ± 0.39; GG 7.11 ± 1.05 BAP (U/L): AA 23.98 ± 1.17; AG 21.26 ± 0.98; GG 21.71 ± 3.60 | Positive | It suggests that in women with the 172TT genotype, a lycopene-rich diet is associated with lower bone resorption markers and may reduce the overall risk of osteoporosis. |

| Rão et al., 2007 [37] (Canada) | Clinical study | 33 postmenopausal women (four groups, record diet G1; G2; G3; G4) The participants were grouped according to quartiles of serum lycopene per kg body weight (nM/kg). Age in years: 56.33 ± 0.45 | Women between 50–60 years old who were at least one year postmenopausal | Participants were asked to sign an informed consent form, record their diet for seven days, and give a 12 h fasting blood sample on the eighth day. | ELISA; lipid peroxidation measurement; protein oxidation (thiols) measurement. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis | Protein thiols (μM): G1: 504.2 ± 16.3; G2: 501.9 ± 25.; G3: 457.4 ± 50.1: G 4: 592.2 ± 31.1 TBARS (nmol/mL serum): G1: 7.4 ± 1.01; G2: 5.1 ± 0.30; G3: 5.04 ± 0.6; G4: 5.5 ± 0.59 NTx (nM BCE): G1: 22.5 ± 2.2; G2: 27.1 ± 2.3; G 3: 24.5 ± 1.4; G4: 17.1 ± 1.3; BAP (U/L): G1: 23.0 ± 2.7; G2: 20.7 ± 2.6; G3: 21.7 ± 3.3; G4: 21.3 ± 2.0 | Positive | The lycopene in the participants’ daily diet appeared to be bioavailable and may help reduce bone resorption in postmenopausal women. |

| Authors, Year (Location) | G1: Lycopene Use G2: Comparison Group Number of Subjects (n); Mean Age | Characteristics of the Samples Included | Administration Protocol Lycopene | Assessments Method | Outcomes: Results | Intervention Effect | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xia et al., 2024 [28] (China) | G1.1: LYC low-dose (LYCL) 15 mg/kg; G1.2: LYC high-dose (LYCH) 30 mg/kg; G2.1: SHAM with equal volume of sunflower oil; G2.2: ovariectomized the equal volume of sunflower oil; G2.3: estradiol valerate 0.1 mg/kg in sunflower oil; 10 per group; 230 ± 10 g, 11 weeks age | Ovariectomized and sham rats | (LYCH, 30 mg/kg; LYCL, 15 mg/kg) dissolved in sunflower oil, respectively (intragastric administration) | ELISA, Alizarin Red S staining, pathologic oil Red O staining, micro-CT, bone biomechanical strength assay, immunohistochemistry | G1.1/G1.2/G2.1/G2.2/G2.3 Trabecular thickness (mm): 1.93 ± 0.037; G1.2: 1.91 ± 0.033/1.90 ± 0.06/1.82 ± 0.03/1.9 ± 0.02 Bone mineral density (g/cm3): 0.13 ± 0.01/0.14 ± 0.01/0.12 ± 0.01/0.1 ± 0.01/0.12 ± 0.0 Bone volume (mm): G1: 38 ± 5; G1.2: 35 ± 1; G2: 40 ± 3.5; G2.1: 25 ± 2; G2.2: 37 ± 2.1 | Positive | Lycopene may attenuate bone loss through the promotion of osteogenesis and inhibition of adipogenesis via the regulation of redox homeostasis in OVX rats. |

| Ricardo et al., 2023 [39] (Brazil) | G1: ovariectomized + LYC (OvxL) 45 mg/kg LYC) G2.1: ovariectomized (Ovx) 45 mg/kg water G2.2: surgery simulation: sham 15 female rats (5/group) (200 g) | Ovariectomized and sham rats | Lycopene 10% was diluted in water in the concentration of 45 mg/kg and administered daily by gavage the day after ovariectomy surgery for 16 weeks | Morphological and morphometrical analyses | G1/G2.1/G2.2 Neoformed bone area (mm2): 13.52 ± 3.38/5.62 ± 2.48/5.69 ± 3.61 Neoformed bone percentage: 26.36 ± 4.44/12.6 ± 2.49/16.69 ± 6.12 | Positive | Lycopene at a concentration of 45 mg/kg stimulates bone repair, promoting significant bone formation in the absence of estrogenic hormone |

| Wang et al., 2023 [38] (China) | G1:SAMP6 + LYC (SAMP6 + LYC) 10 mg LYC dissolved in corn oil G2.1: SAMP 6 + Veh-gavage with corn oil (5 mL kg−1 day−1). G2.2: SAMR1 + Veh-gavaged with corn oil (5 mL kg−1 day−1) corn oil 30 male mice (10 per group)—3 months | Senile osteoporosis | Mice in the SAMP6 + LYC group were gavaged with lycopene (50 mg kg−1 day−1) dissolved in corn oil (10 mg lycopene mL−1) for 8 weeks. | Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, micro-CT, Serum biomarkers analysis, histology and histomorphometry, immunohistochemical analysis, Western blot assay, quantitative real-time PCR | G1/G2.1/G2.2 Trabecular thickness (um): 45 ± 1.41/42 ± 1.41/56 ± 1.41 Bone mineral density total (mg/cm2): 220 ± 14.14/150 ± 7.1/250 ± 7.1 Bone volume (%): 12 ± 1.1/7 ± 1.1/16 ± 2.1 Total bone mineral content (mg): 180 ± 14.4/120 ± 17.7; 125 ± 14.4 | Positive | Demonstrate that the dietary intake of lycopene may provide a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of aging-related osteoporosis |

| Semeghini et al., 2022 [30] (Brazil) | G1: ovariectomized + LYC (OVX/Lyc)−1 mL of the solution containing 10 mg/kg of lycopene/n = 5 G2.1: (OVX)/the same volume of filtered water without lycopene/n = 5 G2.2: sham (control) the same volume of filtered water without lycopene//n = 5 Fifteen 2-month-old female rats | Ovariectomized and sham rats | Daily intragastric administration by oral gavage of 10 mg/kg body weight lycopene 10% was conducted for a period of 8 weeks | Micro-CT, quantitative gene expression—real-time PCR, stereological analysis | G1/G2.1/G2.2 Trabecular number (1/mm): 2.7 ± 0.1/G2: 2.3 ± 0.1/2.6 ± 0.1 Bone surface (mm2): 50 ± 3/130 ± 7/150 ± 7 Bone volume (mm3): 4.1 ± 0.1/3.7 ± 0.1/4.8 ± 0.1 Number of osteoblasts: 9000 ± 636/6000 ± 141.4/5500 ± 282 Number of osteoclasts: 1000 ± 35/3000 ± 70/5000 ± 141 Number of osteocytes: 60,000 ± 14,142.13/50,000 ± 1414/60,000 ± 707 | Positive | Lycopene influences bone metabolism and may be a factor aiding in the prevention of bone loss occurring with the onset of osteoporosis |

| Xia et al., 2022 [29] (China) | G1: LYC 15 mg/kg G2.1: high-fat diet G2.2: metformin (500 mg/kg G2.3: normal control 9 per group; male mice (20 ± 2 g) | High-fat diet-induced Obese mice | Lycopene (15 mg/kg, dissolved in sunflower oil) for an additional 10 weeks. | Micro-CT, bone biomechanical strength and material profile assays, immunohistochemical analysis | G1/G2.1/G2.2/G2.3 Bone mineral density (g/cm3): 1.5 ± 0.07/1.5 ± 0.07/G2.1: 1.5 ± 0.07/1.5 ± 0.07 Bone surface density (mm): 9 ± 2.1/7 ± 1.4/7 ± 3.5/8 ± 2.1 Trabecular thickness (mm): 0.85 ± 0.38/0.8 ± 0.03/0.7 ± 0.49/0.8 ± 0.07 Cortical bone area (mm2): 1.1 ± 0.1/1.2 ± 0.1/1.3 ± 0.1/1.0 ± 0.1 | Positive | Dietary supplementation of lycopene may offer a new therapeutic strategy for the management of obesity and its associated-osteoporosis |

| Mannino et al., 2022 [40] (Italy) | G1: (MP + LYCO) G2.1: (MP + Ale) G2.2: (MP + GEN) G2.3: (MP + GEN + LYCO) G2.4: SHAM G2.5: (MP) 10 per group; female Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (n = 60), 5 months of age (250–275 g) | Osteoporosis glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis rats | All treatments were daily administered per os through gavage and lasted an additional 60 days with lycopene 10 mg/kg days and associations | RT-qPCR, histology, micro-CT | G1/G2.1/G2.2/G2.3/G2.4/G2.5 Trabecular thickness (micron): 70 ± 5. 65/72 ± 2.12/62 ± 9.89/71 ± 8.42/78 ± 2.82/60 ± 2.12 Bone mineral density (mg/cm3): 620 ± 63.6/700 ± 35.3/600 ± 77.7/650 ± 98/780 ± 84/430 ± 28 Bone volume (BV) (Trabecular): 28% ± 1/30% ± 3/25% ± 3/28%± 5/30% ± 2/22% ± 2 Bone volume (BV) Cortical: 64% ± 4.2/62% ± 5.6/58% ± 7.1/64% ± 5/75% ± 5.64/50% ± 5 | Positive | Combined treatment of genistein and lycopene significantly restored normal architecture and adequate interconnectivity between the bone trabeculae, thus increasing BMD levels |

| Qi et al., 2021 [41] (China) | G1.1: (LYC-L) G1.2: (LYC-H) G2.1: (control) G2.2: (diabetic) G2.2: (metformin) Female rats, 8 weeks old 12 per group; (210 g~223 g) | Diabetic rats | G1.1: (LYC-L): treated with lycopene 50 mg/kg/day G1.2: (LYC-H): treated with lycopene 100 mg/kg/day oral gavage for 10 weeks | Micro-CT, bone mechanical parameters measurement, ELISA, bone histomorphometry | G1.1/G1.2/G2.1/G2.2 Trabecular thickness (mm) 0.8 ± 0.1/0.9 ± 0.5/0.1 ± 0.01/0.6 ± 0.1/0.9 ± 0.49 Bone volume (mm3): 5.30 ± 0.14/5.8 ± 0.14/7.5 ± 0.70/3.0 ± 0.14/6.5 ± 0.07 Bone surface area (mm2) 170 ± 14.14/200 ± 7.07/230 ± 10.60/110 ± 3.53/180 ± 14.14 Trabecular volume (mm3): 32 ± 2.1; 33 ± 2.1/41 ± 0.1/22 ± 1.1/34 ± 2.8 | Positive | Lycopene could prevent diabetic induced bone loss via anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, inhibiting bone resorption, upregulating OPG/RANKL ratio, and regulating abnormal bone turnover |

| Oliveira et al., 2019 [32] (Brazil) | G1.1: sham + daily intake of 10 mg/kg of LYC for 30 day G1.2: sham + daily intake of 10 mg/kg of LYC for 60 days G1.3: OVX + daily intake of 10 mg/kg of LYC for 30 day G1.4: OVX + daily intake of 10 mg/kg of LYC for 60 days G2.1: sham group G2.2: OVX 3 per group, Wistar female rats weighing approximately 300 g | Ovariectomized and sham rats osteoporosis | Lycopene (10 mg/kg weight per day) dissolved in filtrated water by daily intragastric administration for experimental periods of 30 and 60 days. The group that received 30 days of lycopene had the administration substituted for filtrated water for the other 30 days until killing | Alizarin Red S, real-time PCR, In situ alkaline phosphatase assay, alkaline phosphatase activity, mineralized matrix formation and real-time PCR, histomorphometry | G1.1/G1.2/G1.3/G1.4/G2.1/G2.2 Trabecular bone (%): 30 ± 2.12/32 ± 1.41/23 ± 0.70/30 ± 0.70; 35 ± 0.70/12 ± 1.41 | Positive | Daily intake of lycopene for 30 or 60 days decreased bone loss in femur epiphysis. Thus, lycopene might be a potential adjuvant to drug therapy used in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis |

| Mityas et al., 2019 [42] (Egypt) | G1.1: LYC 30 mg/kg G1.2 LYC + prednisolone G2.1: (control) G2.2: prednisolone 10 per group; adult male rats 150–200 g | Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis rats | G1: lycopene orally 30 mg/kg once daily for 8 weeks; G2: lycopene orally at a dose of 30 mg/kg BW once daily and prednisolone orally at a dose of 20 mg/kg BW once daily for 8 weeks | Hematoxylin and eosin stain; Mallory’s trichrome stain, C-scanning electron microscopy | G1.1/G1.2/G2.1/G2.2 Area percentage—collagen fiber contents: 32.4 ± 4.6/30.0 ± 4.5/31.2 ± 3.5/16.5 ± 4.1 | Positive | It is recommended that lycopene can be used as a dietary alternative to drug therapy or as a supplement to people at risk for osteoporosis |

| Li et al., 2018 [43] (China) | G1: OVX + LYC G2.1: OVX G2.2: SHAM Thirty female (ten per group) Sprague–Dawley rats aged 12 weeks old with a weight of 245 ± 7.46 g | Ovariectomized rats | Lycopene (50 mg/kg/day) | Biomechanical tests, micro-CT, histological analysis | G1/G2.1/G2.2 Bone mineral density(mg/cc): 160 ± 17.8/140 ± 14.1/170 ± 14.1 Trabecular thickness (μm): 125 ± 7.07/100 ± 17.67/130 ± 9.19 Bone volume (%): 25 ± 2.1/18 ± 1.4/24 ± 4.2 Trabecular separation: 560 ± 7/600 ± 14/530 ± 17 Trabecular number: 1.6 ± 0.2/1.5 ± 0.1/1.7 ± 0.1 | Positive | Lycopene significantly increased implant osseointegration, fixation, and bone mass in OVX rats to the level of those in sham rats |

| Ardawi et al., 2016 [17] (Saudi Arabia) | G1.1: LYC-supplemented (15 mg/kg weight per day) G1.2: LYC-supplemented (30 mg/kg weight per day); G1.3 OVX lycopene-supplemented (45 mg/kg per day); G2.1: OVX alendronate-treated (ALN) [2.0 μg/kg body weight per day subcutaneously; G2.2: sham-operated; G2.3: ovariectomized control 44 animals per group Six-month-old female rats (n = 264) | Ovariectomized and sham rats | The lycopene-supplemented groups were given lycopene (15, 30, and 45 mg/kg body weight per day) dissolved in corn oil by daily intragastric administration for the experimental period of 12 weeks. The SHAM, OVX, and ALN control groups were given the same volume of corn oil without lycopene treatment | 858 Mini Bionex Servohydraulic Test System; micro-CT | G1.1/G1.2/G1.3/G2.1/G2.2/G2.3 μCT: relative bone volume (%) 17.6 ± 1.6/26.7 ± 1.9/31.6 ± 1.8/32.3 ± 1.9/31.0 ± 1.4/14.1 ± 0.3 Trabecular number (mm): 3.9 ± 0.1/4.8 ± 0.2/5.2 ± 0.1/5.1 ± 0.1/5.1 ± 0.1/3.4 ± 0.1 Trabecular thickness (mm): 0.07 ± 0.0/0.07 ± 0.01/0.09 ± 0.01/0.08 ± 0.01/0.08 ± 0.01/0.07 ± 0.01; Femur diaphysis—relative bone volume (%): 62.04 ± 0.60/65.00 ± 0.49/66.77 ± 0.99/67.45 ± 0.73/65.19 ± 0.67/61.88 ± 0.67 Cortical thickness (mm): 0.624 ± 0.011/0.69 ± 0.012/0.7 ± 0.01/0.7 ± 0.01/0.65 ± 0.01/0.615 ± 0.01 Cortical porosity (%): 0.180 ± 0.01/0.21 ± 0.00/0.22 ± 0.01/0.23 ± 0.01/0.21 ± 0.01/0.28 ± 0.01 | Positive | Lycopene treatment for 12 weeks demonstrated bone-protective effects similar to ALN, improving the biomechanical properties of bone and inhibiting bone resorption in OVX rats |

| Iimura et al., 2015 [18] (Japan) | G1.1: LYC 50 mg/kg, n = 9 G1.2: LYC 100 mg/kg, n = 9 G1.3: LYC 200 mg/kg, n = 9 G2: lycopene 0 mg/kg, n = 6 Female 6-week-old rats (n = 33) | Ovariectomized rats | Based on the lycopene content in their diet (0, 50, 100, and 200 ppm (mg lycopene/kg diet)); lycopene was incorporated into the diet as a tomato extract at 6% | HPLC analysis.; dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; ELISA, d-ROMs test, biological antioxidant potential (BAP) test | G1.1/G1.2/G1.3/G2 Serum bone-type ALP (mU): 56.1 ± 4/56 ± 4.7/47 ± 3.6/59 ± 3.4 Serum d-ROMs level (U. CARR): 224 ± 15/235 ± 9/216 ± 11/239 ± 8 Serum BAP (l mol): 2738 ± 81/2741 ± 61/2851 ± 63/±75 Serum BAP/d-ROMs ratio: 12.2 ± 0.6/11.8 ± 0.5/13.4 ± 0.4/11.9 ± 0.6 8-OHdG excretion (lg/day): 1.2 ± 0.1/1.3 ± 0.3/1.5 ± 0.3/1.0 ± 0.2 | Positive | Lycopene intake significantly inhibited bone resorption, thereby suppressing bone loss in ovariectomized rats, but failed to alter the systemic oxidative stress level |

| Iimura et al., 2014 [44] (Japan) | G1.1: LYC 50 mg/kg; G1.2: LYC 100 mg/kg; G2: LYC 0 mg/kg; 8 per group; Six-week-old female rats | Growing female rats | According to the lycopene content in their diet: 0, 50, and 100 ppm. Lycopene was incorporated into the diet as a tomato extract containing 6% lycopene | Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, femoral mechanical braking test, urinary deoxypyridinoline, serum bone type ALP activity | G1.1/G1.2/G2 Femoral breaking force: 21.19 ± 0.40/21.05 ± 0.29/20.41 ± 0.48 Femoral breaking energy: 12.8 ± 0.88/13.8 ± 1.24/12.1 ± 1.1 Bone turnover markers (nmol/mg): 0.19 ± 0.03/0.2 ± 0.03/0.34 ± 0.5 Serum ALP: 44.9 ± 4.6/48.6 ± 4.1/35.7 ± 2.1 | Positive | Lycopene intake facilitated bone formation and inhibited bone resorption, which contributed to an increase in the BMD of growing female rats |

| Liang et al., 2012 [45] (China) | G1.1: OVX lycopene 20 mg/kg body weight G1.2: OVX lycopene 30 mg/kg G1.3: OVX lycopene 40 mg/kg G2.1: control group (OVX) G2.2: placebo group n = 50–2-month-old female rats (body weight 225 ± 10 g) | Ovariectomized mature rats | Lycopene 20, 30, and 40 mg/(kg body weight day) dissolved in corn oil, respectively, by intragastric administration for 8 weeks | X-ray absorptiometry; analysis of serum Ca, P concentration and serum ALP, IL-6, estrogen, BGP, ELISA; three-point bending test | G1.1/G1.2/G1.3/G2.1/G2.2 Serum Ca, P, and ALP Ca (mmol/L): 2.55 ± 0.22/G1.2: 2.52 ± 0.21/2.45 ± 0.25/2.4 ± 0.17/2.61± 0.19 P (mmol/L): 1.56 ± 0.18/1.5 ± 0.16/1.4 ± 0.2/1.3 ± 0.2/: 1.6 ± 0.2 ALP (U/L): 83.4 ± 7.32/79.22 ± 6.83/71.33 ± 8.28/60.5 ± 4.8/98.3 ± 6.9 | Positive | Lycopene treatment can inhibit bone loss and increase bone strength in OVX rats |

| Pei et al., 2008 [46] (China) | G1.1: LYC: 10 mg/(kg) G1.2: LYC 15 mg/(kg) G1.3: LYC 20 mg/(kg) G2.1: Nylestriol (estrogen) G2.2: white group G2.3: control n = 72, 15-week-old SD rats | Ovariectomized rats | The nialestradiol group was given 1.05 mg/(kg-bw) by gavage, and the high, medium, and low doses of lycopene were given at 20, 15, and 10 mg/(kg-bw) by gavage. 12 weeks. The blank group and the model group received water | Chromatography, serum estradiol, serum ALP and uterus index, length bone mineral density, bone mineral | G1.1/G1.2/G1.3/G2.1/G2.2/G2.3 Bone mineral content (mg): 101.3 ± 9.0/104.5 ± 1/107.1 ± 10/112. 6 ± 6/98.13 ± 9.1/87.4 ± 7.0 Bone density BMC mg): 65.8 ± 5.0/67.2 ± 5.1/69.3 ± 5.0/78.6 ± 5.8/66.6 ± 4.4/55.2 ± 4.0 | Positive | In short, lycopene has an estrogen-like effect. Effective in improving the occurrence of osteoporosis caused by postmenopause |

| Studies | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed Cohort | Non Exposed Cohort | Ascertainment of Exposure | Outcome of Interest Not Present at Start | Main Factor | Additional Factor | Assessment of Outcome | Follow-Up Long Enough | Adequacy of Follow-Up | ||

| Russo et al., 2020 [11] | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 8 |

| Mackinnon et al., 2011 [34] | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 0 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 8 |

| Mackinnon et al., 2010 [36] | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 0 | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 8 |

| Rão et al., 2007 [37] | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | ✰ | 0 | ✰ | 0 | ✰ | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, A.N.A.; Nunes, G.P.; Domingues, D.V.A.d.P.; Toninatto Alves De Toledo, P.; Akinsomisoye, O.S.; Florencio-Silva, R.; Cerri, P.S. Effects of Lycopene Supplementation on Bone Tissue: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Evidence. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18081172

Silva ANA, Nunes GP, Domingues DVAdP, Toninatto Alves De Toledo P, Akinsomisoye OS, Florencio-Silva R, Cerri PS. Effects of Lycopene Supplementation on Bone Tissue: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Evidence. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(8):1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18081172

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Arles Naisa Amaral, Gabriel Pereira Nunes, Danilo Vinicius Aparecido de Paula Domingues, Priscila Toninatto Alves De Toledo, Olumide Stephen Akinsomisoye, Rinaldo Florencio-Silva, and Paulo Sérgio Cerri. 2025. "Effects of Lycopene Supplementation on Bone Tissue: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Evidence" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 8: 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18081172

APA StyleSilva, A. N. A., Nunes, G. P., Domingues, D. V. A. d. P., Toninatto Alves De Toledo, P., Akinsomisoye, O. S., Florencio-Silva, R., & Cerri, P. S. (2025). Effects of Lycopene Supplementation on Bone Tissue: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Preclinical Evidence. Pharmaceuticals, 18(8), 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18081172