The Role of Vitamin D in the Management of Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

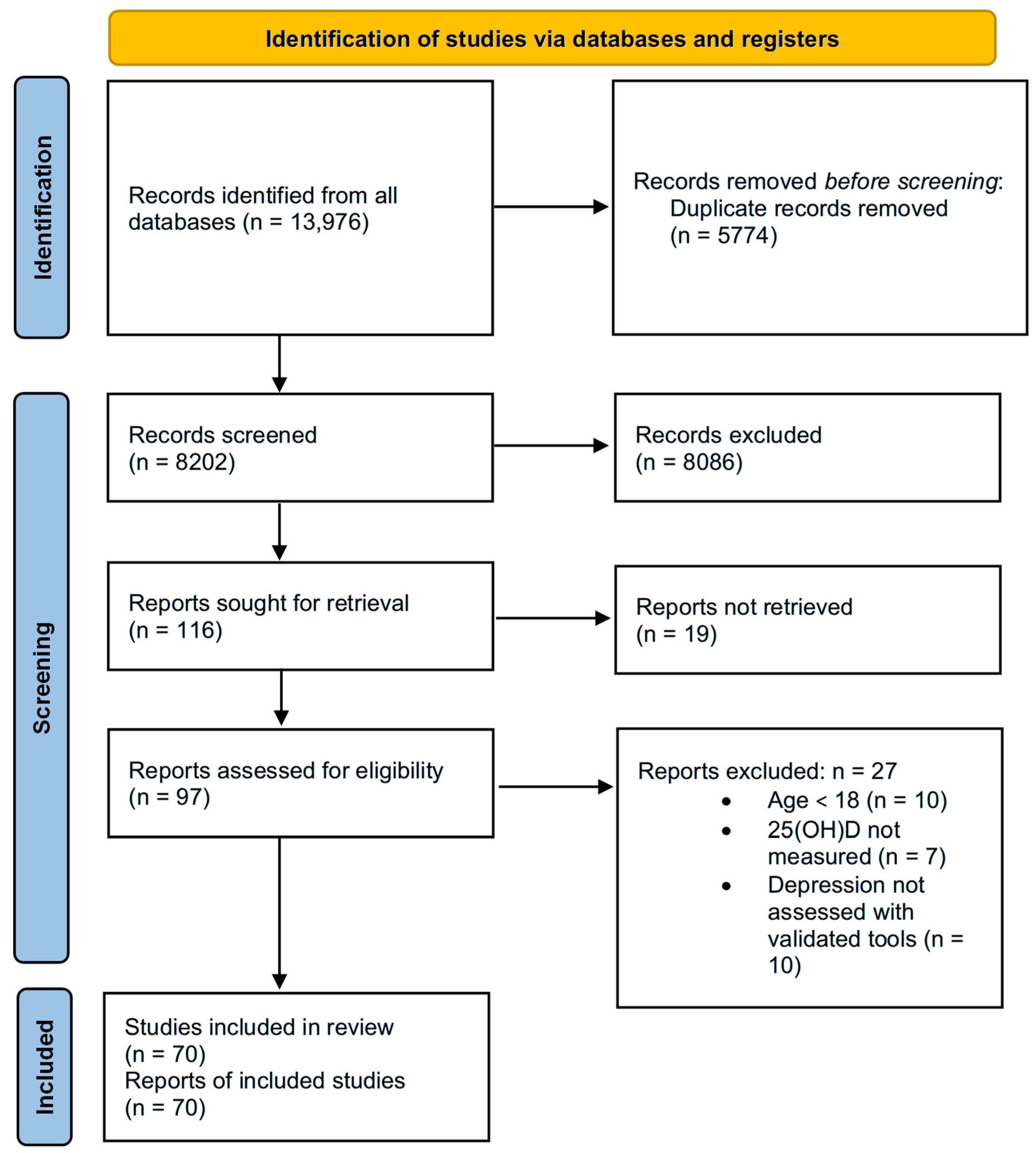

2. Methods

2.1. Study Eligibility, Inclusion Criteria, and Exclusion Criteria

- Studies conducted on adults aged 18 years or older;

- Observational studies (such as cross-sectional, cohort, and case–control studies) and interventional studies (RCTs);

- Studies that assessed the relationship between vitamin D and depression;

- Studies that evaluated the effect of vitamin D supplementation in relation to depressive symptomatology;

- Studies in which vitamin D levels were determined by measuring serum 25(OH)D concentrations;

- Studies employing validated instruments to quantify depressive symptomatology;

- Articles published in English.

- Studies that included participants under the age of 18;

- Studies conducted on animal models;

- In vitro studies;

- Articles published in a language other than English;

- Studies for which the full text was not available.

2.2. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results and Discussion

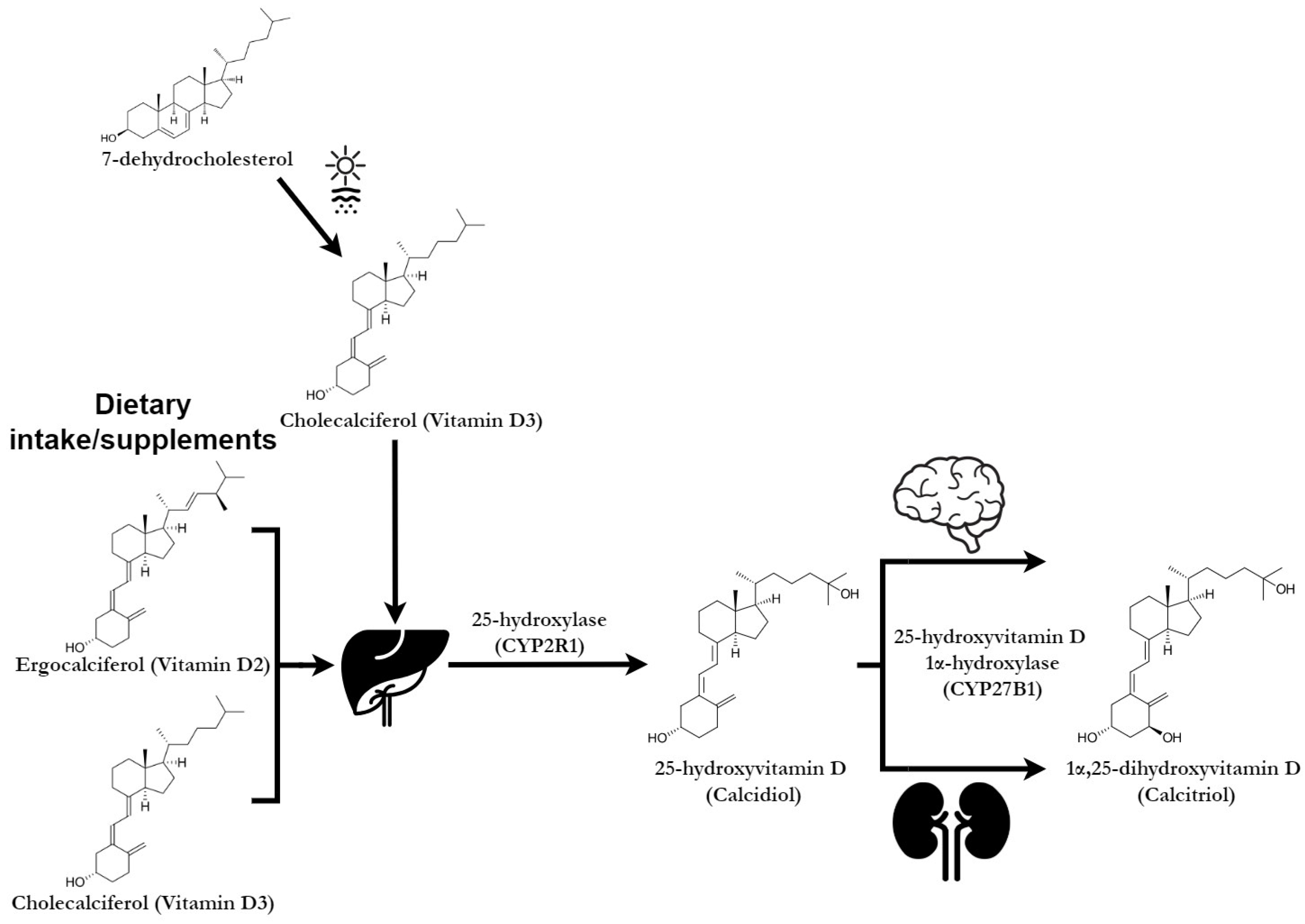

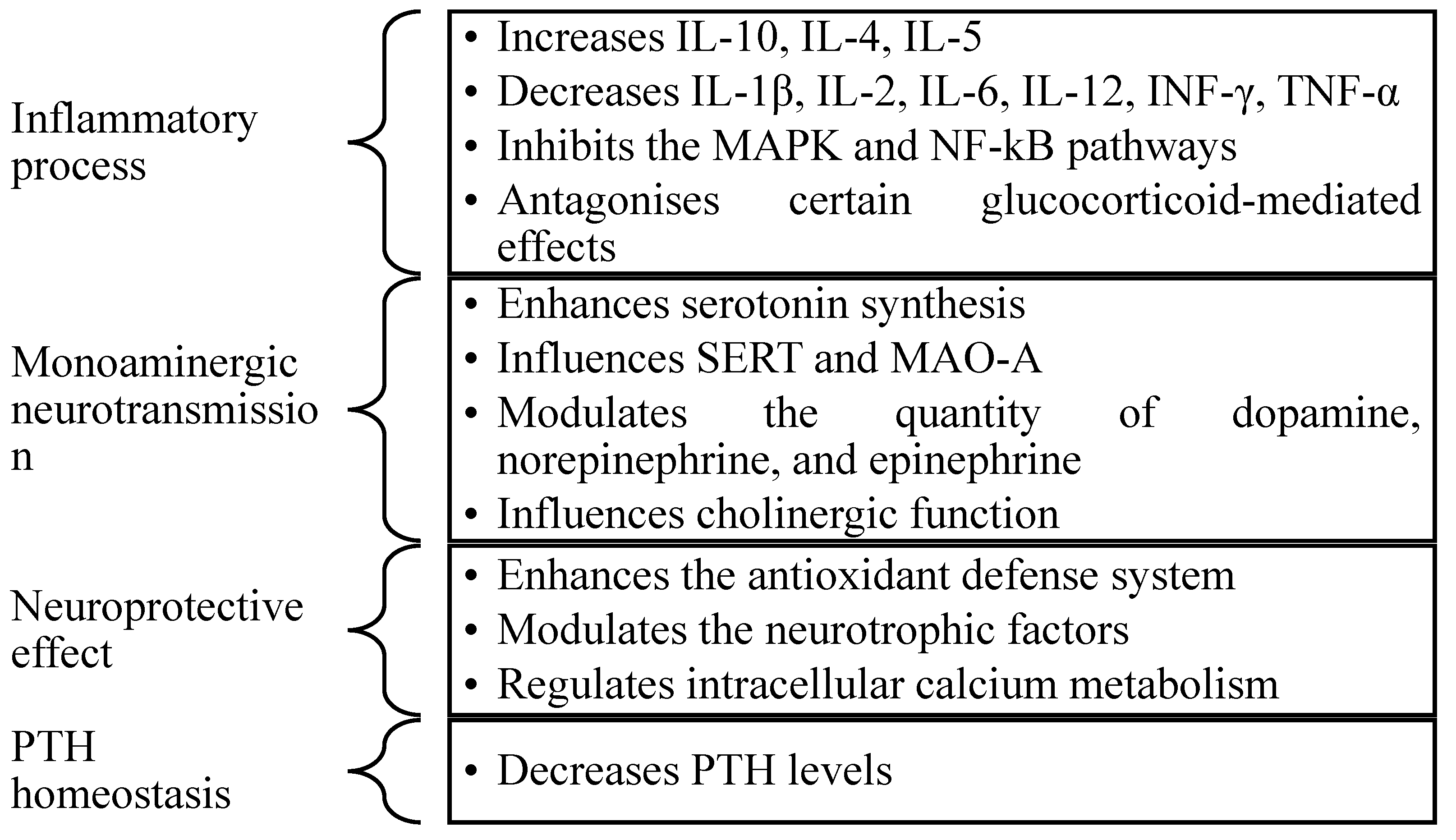

3.1. The Implication of Vitamin D in the Pathophysiology of Depression

3.2. The Relationship Between Serum Vitamin D Levels and Depression

3.3. The Role of Vitamin D Supplementation in Depressive Symptoms

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stahl, S.M. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications, 4th ed.; MPG Books Group: Bodmin, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Albuloshi, T.; Dimala, C.; Kuhnle, G.; Bouhaimed, M.; Dodd, G.; Spencer, J. The effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation in reducing depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 6, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.; Chin, K.-Y.; Ima-Nirwana, S. Vitamin D and Depression: The Evidence from an Indirect Clue to Treatment Strategy. Curr. Drug Targets 2018, 19, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, L.; Brahmbhatt, A. Depression in Primary Care. J. Nurse Pr. 2021, 17, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiri, B.; Sarbakhsh, P.; Vafa, M. Randomized study of the effects of vitamin D and/or magnesium supplementation on mood, serum levels of BDNF, inflammation, and SIRT1 in obese women with mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 2123–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaemi, S.; Zeraattalab-Motlagh, S.; Jayedi, A.; Shab-Bidar, S. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on depression: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 3999–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan-Mihan, A.; Stevens, P.; Medero-Alfonso, S.; Brace, G.; Overby, L.K.; Berg, K.; Labyak, C. The Role of Water-Soluble Vitamins and Vitamin D in Prevention and Treatment of Depression and Seasonal Affective Disorder in Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Caballero, L.; Torres-Sanchez, S.; Romero-López-Alberca, C.; González-Saiz, F.; Mico, J.A.; Berrocoso, E. Monoaminergic system and depression. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 377, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobis, A.; Zalewski, D.; Waszkiewicz, N. Peripheral Markers of Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budni, J.; Moretti, M.; Freitas, A.E.; Neis, V.B.; Ribeiro, C.M.; de Oliveira Balen, G.; Rieger, D.K.; Leal, R.B.; Rodrigues, A.L.S. Behavioral and neurochemical effects of folic acid in a mouse model of depression induced by TNF-α. Behav. Brain Res. 2021, 414, 113512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.P.; Pareek, M.; Hvolby, A.; Schmedes, A.; Toft, T.; Dahl, E.; Nielsen, C.T. Vitamin D3 supplementation and treatment outcomes in patients with depression (D3-vit-dep). BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, M.; Nikooyeh, B.; Etesam, F.; Behnagh, S.J.; Kangarani, H.M.; Arefi, M.; Yaghmaei, P.; Neyestani, T.R. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on depression and some selected pro-inflammatory biomarkers: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libuda, L.; Timmesfeld, N.; Antel, J.; Hirtz, R.; Bauer, J.; Führer, D.; Zwanziger, D.; Öztürk, D.; Langenbach, G.; Hahn, D.; et al. Effect of vitamin D deficiency on depressive symptoms in child and adolescent psychiatric patients: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 3415–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Neeraj, D.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Yang, W.; Guan, N. Latent profile analysis of vitamin D and its association with depression severity of hospitalized patients with bipolar depression. Nutr. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brîndușe, L.A.; Eclemea, I.; Neculau, A.E.; Cucu, M.A. Vitamin D Status in the Adult Population of Romania—Results of the European Health Examination Survey. Nutrients 2024, 16, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, F.; Nasiri, S.; Tavana, Z.; Dabbaghmanesh, M.H.; Sharif, F.; Jafari, P. A randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation on perinatal depression: In Iranian pregnant mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.-M.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yu, Y. The Relationship Between Serum Concentration of Vitamin D, Total Intracranial Volume, and Severity of Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casseb, G.A.S.; Kaster, M.P.; Rodrigues, A.L.S. Potential Role of Vitamin D for the Management of Depression and Anxiety. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoza-Moncada, M.M.; Turrubiates-Hernández, F.J.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Gutiérrez-Brito, J.A.; Díaz-Pérez, S.A.; Aguayo-Arelis, A.; Hernández-Bello, J. Vitamin D in Depression: A Potential Bioactive Agent to Reduce Suicide and Suicide Attempt Risk. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.M.; Grandoff, P.G.; Schneider, S.T. Vitamin D Intake and Factors Associated with Self-Reported Vitamin D Deficiency Among US Adults: A 2021 Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 899300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.R.; Senior, P.A.; Mager, D.R. Vitamin D supplementation and health-related quality of life: A systematic review of the literature. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, W.K.; Penny, J.L.; Rothschild, A.J. Vitamin D supplementation in bipolar depression: A double blind placebo controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 95, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajac, I.T.; Barnes, M.; Cavuoto, P.; Wittert, G.; Noakes, M. The Effects of Vitamin D-Enriched Mushrooms and Vitamin D3 on Cognitive Performance and Mood in Healthy Elderly Adults: A Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, K.M.; Stuart, A.L.; Williamson, E.J.; Jacka, F.N.; Dodd, S.; Nicholson, G.; Berk, M. Annual high-dose vitamin D3 and mental well-being: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 198, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyles, D.W.; Burne, T.H.; McGrath, J.J. Vitamin D, effects on brain development, adult brain function and the links between low levels of vitamin D and neuropsychiatric disease. Front. Neuroendocr. 2013, 34, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Sun, D.; Wang, A.; Pan, H.; Feng, W.; Ng, C.H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Tao, L.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; et al. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Depression in Older Adults: A Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 1192–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, C.; Shaikh, A.S.; Han, W.; Chen, D.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, P. Vitamin D and depression: Mechanisms, determination and application. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 28, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartagni, M.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Tartagni, M.V.; Alrasheed, H.; Matteo, M.; Baldini, D.; De Salvia, M.; Loverro, G.; Montagnani, M. Vitamin D Supplementation for Premenstrual Syndrome-Related Mood Disorders in Adolescents with Severe Hypovitaminosis D. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016, 29, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidgren, M.; Virtanen, J.K.; Tolmunen, T.; Nurmi, T.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Voutilainen, S.; Ruusunen, A. Serum Concentrations of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Depression in a General Middle-Aged to Elderly Population in Finland. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Emon, P.Z.; Shahriar, M.; Nahar, Z.; Islam, S.M.A.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Islam, S.N.; Islam, R. Higher levels of serum IL-1β and TNF-α are associated with an increased probability of major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouba, B.R.; Borba, L.d.A.; de Souza, P.B.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Rodrigues, A.L.S. Role of Inflammatory Mechanisms in Major Depressive Disorder: From Etiology to Potential Pharmacological Targets. Cells 2024, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, G.; Gustafsson, S.A.; Hällström, T.; Gustafsson, T.; Klawitter, B.; Petersson, M. Depressed adolescents in a case-series were low in vitamin D and depression was ameliorated by vitamin D supplementation. Acta Paediatr. 2012, 101, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudet, C.; Malm, J.; Westrin, A.; Brundin, L. Suicidal patients are deficient in vitamin D, associated with a pro-inflammatory status in the blood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 50, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenercioglu, A.K. The Anti-Inflammatory Roles of Vitamin D for Improving Human Health. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 13514–13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikaroudi, M.K.; Mokhtare, M.; Shidfar, F.; Janani, L.; Kashani, A.F.; Masoodi, M.; Agah, S.; Dehnad, A.; Shidfar, S. Effects of vitamin D3 supplementation on clinical symptoms, quality of life, serum serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), 5-hydroxy-indole acetic acid, and ratio of 5-HIAA/5-HT in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. EXCLI J. 2020, 19, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humble, M.B. Vitamin D, light and mental health. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2010, 101, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, V.; Kar, S.K.; Suthar, N.; Nebhinani, N. Vitamin D and Depression: A Critical Appraisal of the Evidence and Future Directions. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi-Naeeni, M.; Dolatian, M.; Qorbani, M.; Vaezi, A.A. Effect of omega-3 and vitamin D co-supplementation on psychological distress in reproductive-aged women with pre-diabetes and hypovitaminosis D: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.A.; Sink, K.M.; Tooze, J.A.; Atkinson, H.H.; Cauley, J.A.; Yaffe, K.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Rubin, S.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; et al. Low 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations Predict Incident Depression in Well-Functioning Older Adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2015, 70, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, M.J. Vitamin D and Depression: Cellular and Regulatory Mechanisms. Pharmacol. Rev. 2017, 69, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, H.T.; Bair, T.L.; Lappé, D.L.; Anderson, J.L.; Horne, B.D.; Carlquist, J.F.; Muhlestein, J.B. Association of vitamin D levels with incident depression among a general cardiovascular population. Am. Hear. J. 2010, 159, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalzadeh, L.; Saghafi, M.; Mortazavi, S.S.; Jolfaei, A.G. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in obese adults: A comparative observational study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.-Y.; Guo, Y.-J.; Wang, K.-Y.; Chen, L.-M.; Jiang, P. Neuroprotective effects of vitamin D and 17ß-estradiol against ovariectomy-induced neuroinflammation and depressive-like state: Role of the AMPK/NF-κB pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 86, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, G.B.; Brotchie, H.; Graham, R.K. Vitamin D and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C.; Sai, A.; Templin, T.; Smith, L. Dose response to Vitamin D supplementation in postmenopausal women: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitamin D—Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Park, Y.; Ah, Y.-M.; Yu, Y.M. Vitamin D supplementation for depression in older adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1169436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Yan, M.; Jing, B.; Yu, H.; Li, W.; Guo, Q. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms in older patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1467234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.; Alsulami, N.; Khoja, S.; Alsufiani, H.; Tayeb, H.O.; Tarazi, F.I. Vitamin D Supplementation Ameliorates Severity of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 70, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C.; Peacock, M.; Yalamanchili, V.; Smith, L.M. Effects of vitamin D supplementation in older African American women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Hoogendijk, W.; Lips, P.; Heijboer, A.C.; Schoevers, R.; van Hemert, A.M.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Smit, J.H.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. The association between low vitamin D and depressive disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglin, R.E.S.; Samaan, Z.; Walter, S.D.; McDonald, S.D. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M.; Łuszczki, E.; Dereń, K. Dietary Nutrient Deficiencies and Risk of Depression (Review Article 2018–2023). Nutrients 2023, 15, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.-J.; Jeong, S.-N. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, T.A.; Sabry, W.M.; Hashim, M.A.; Abdeen, M.S.; Abdelhamid, A.M. Vitamin D serum level in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2020, 27, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherchand, O.; Sapkota, N.; Chaudhari, R.K.; A Khan, S.; Baranwal, J.K.; Pokhrel, T.; Das, B.K.L.; Lamsal, M. Association between vitamin D deficiency and depression in Nepalese population. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 267, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, T.; Knekt, P.; Suvisaari, J.; Männistö, S.; Partonen, T.; Sääksjärvi, K.; Kaartinen, N.E.; Kanerva, N.; Lindfors, O. Higher serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are related to a reduced risk of depression. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoue, T.; Kochi, T.; Akter, S.; Eguchi, M.; Kurotani, K.; Tsuruoka, H.; Kuwahara, K.; Ito, R.; Kabe, I.; Nanri, A. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are associated with increased likelihood of having depressive symptoms among Japanese workers. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaddou, H.Y.; Batieha, A.M.; Khader, Y.S.; Kanaan, S.H.; El-Khateeb, M.S.; Ajlouni, K.M. Depression is associated with low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D among Jordanian adults: Results from a national population survey. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 262, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.M.; Tajar, A.; O’neill, T.W.; O’connor, D.B.; Bartfai, G.; Boonen, S.; Bouillon, R.; Casanueva, F.F.; Finn, J.D.; Forti, G.; et al. Lower vitamin D levels are associated with depression among community-dwelling European men. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 25, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.-M.; Zhao, W.; Cui, S.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.; Yu, Y. The Relationship Between Vitamin D, Clinical Manifestations, and Functional Network Connectivity in Female Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 817607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goltz, A.; Janowitz, D.; Hannemann, A.; Nauck, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Seyfart, T.; Völzke, H.; Terock, J.; Grabe, H.J. Association of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Vitamin D with Depression and Obesity: A Population-Based Study. Neuropsychobiology 2017, 76, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereke, O.I.; Singh, A. The Role of Vitamin D in the Prevention of Late-life Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 198, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.; Hirani, V. Relationship between vitamin D levels and depressive symptoms in older residents from a national survey population. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Lips, P.; Dik, M.G.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Depression is associated with decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D and increased parathyroid hormone levels in older adults. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M.; Dhonukshe-Rutten, R.A.M.; van Wijngaarden, J.P.; van der Zwaluw, N.L.; Sohl, E.; Veld, P.H.I.; van Dijk, S.C.; Swart, K.M.A.; Enneman, A.W.; Ham, A.C.; et al. Low vitamin D status is associated with more depressive symptoms in Dutch older adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, D.; Luo, J.; Wang, Y.; Ju, B.; Lv, X.; Fan, P.; He, L. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in rheumatoid arthritis patients and their associations with serum vitamin D level. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 37, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, C.S.; Grünhage, F.; Baus, C.; Volmer, D.A.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Riemenschneider, M.; Lammert, F. Vitamin D supplementation reduces depressive symptoms in patients with chronic liver disease. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Jafarirad, S.; Amani, R. Postpartum depression and vitamin D: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1514–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centeno, L.O.L.; Fernandez, M.d.S.; Muniz, F.W.M.G.; Longoni, A.; de Assis, A.M. Is Serum Vitamin D Associated with Depression or Anxiety in Ante- and Postnatal Adult Women? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollinshead, V.R.B.B.; Piaskowski, J.L.; Chen, Y. Low Vitamin D Concentration Is Associated with Increased Depression Risk in Adults 20–44 Years Old, an NHANES 2007–2018 Data Analysis with a Focus on Perinatal and Breastfeeding Status. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.; Chan, D.; Woo, J.; Ohlsson, C.; Mellström, D.; Kwok, T.; Leung, P. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and psychological health in older Chinese men in a cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 130, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, C.M.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Cotch, M.F.; Steingrimsdottir, L.; Thorsdottir, I.; Launer, L.J.; Harris, T.; Gudnason, V.; Gunnarsdottir, I. Depression and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in older adults living at northern latitudes—AGES-Reykjavik Study. J. Nutr. Sci. 2015, 4, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanova, O.; Aarts, N.; Noordam, R.; Carola-Zillikens, M.; Hofman, A.; Tiemeier, H. Vitamin D serum levels are cross-sectionally but not prospectively associated with late-life depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017, 135, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Ford, E.S.; Li, C.; Balluz, L.S. No associations between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone and depression among US adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 1696–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Lu, L.; Franco, O.H.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Lin, X. Association between depressive symptoms and 25-hydroxyvitamin D in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 118, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, A.; Naderpoor, N.; de Courten, M.P.; de Courten, B. Vitamin D and symptoms of depression in overweight or obese adults: A cross-sectional study and randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 177, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamanchili, V.M.; Gallagher, J.C. Treatment with hormone therapy and calcitriol did not affect depression in older postmenopausal women: No interaction with estrogen and vitamin D receptor genotype polymorphisms. Menopause 2012, 19, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husemoen, L.L.N.; Ebstrup, J.F.; Mortensen, E.L.; Schwarz, P.; Skaaby, T.; Thuesen, B.H.; Jørgensen, T.; Linneberg, A. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and self-reported mental health status in adult Danes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaneschi, Y.; Shardell, M.; Corsi, A.M.; Vazzana, R.; Bandinelli, S.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Depressive Symptoms in Older Women and Men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 3225–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.; McCarroll, K.; O’Halloran, A.; Healy, M.; Kenny, R.A.; Laird, E. Vitamin D Deficiency Is Associated with an Increased Likelihood of Incident Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, K.S.; Hegeman, J.M.; van den Brink, R.H.; Rhebergen, D.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Marijnissen, R.M. A prospective study into change of vitamin D levels, depression and frailty among depressed older persons. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamilian, H.; Amirani, E.; Milajerdi, A.; Kolahdooz, F.; Mirzaei, H.; Zaroudi, M.; Ghaderi, A.; Asemi, Z. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on mental health, and biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 94, 109651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikola, T.; Marx, W.; Lane, M.M.; Hockey, M.; Loughman, A.; Rajapolvi, S.; Rocks, T.; O’neil, A.; Mischoulon, D.; Valkonen-Korhonen, M.; et al. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 11784–11801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaviani, M.; Nikooyeh, B.; Zand, H.; Yaghmaei, P.; Neyestani, T.R. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on depression and some involved neurotransmitters. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 269, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Nabizade, L.; Yassini-Ardakani, S.M.; Hadinedoushan, H.; Barzegar, K. The effect of 2 different single injections of high dose of vitamin D on improving the depression in depressed patients with vitamin D deficiency. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellekkatt, F.; Menon, V.; Rajappa, M.; Sahoo, J. Effect of adjunctive single dose parenteral Vitamin D supplementation in major depressive disorder with concurrent vitamin D deficiency: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 129, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, N.M.; Khademalhoseini, S.; Vakili, Z.; Assarian, F. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on depression in elderly patients: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2065–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoraminya, N.; Tehrani-Doost, M.; Jazayeri, S.; Hosseini, A.; Djazayery, A. Therapeutic effects of vitamin D as adjunctive therapy to fluoxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2013, 47, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, M.; Mahmoudi, M.; Abshirini, M.; Eshraghian, M.R.; Javanbakht, M.H.; Zarei, M.; Hasani, H.; Djalali, M. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: Randomized placebo-controlled double-blind clinical trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2019, 13, 2375–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penckofer, S.; Byrn, M.; Adams, W.; Emanuele, M.A.; Mumby, P.; Kouba, J.; Wallis, D.E. Vitamin D Supplementation Improves Mood in Women with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 8232863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Vitamin D Deficiency Participates in Depression of Patients with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy by Regulating the Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2024, 20, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, N.; Cooray, M.; Anglin, R.; Muqtadir, Z.; Narula, A.; Marshall, J.K. Impact of High-Dose Vitamin D3 Supplementation in Patients with Crohn’s Disease in Remission: A Pilot Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, A.; Vahedi, H.; Nedjat, S.; Mohamadkhani, A.; Attar, M.J.H. Vitamin D Decreases Beck Depression Inventory Score in Patients with Mild to Moderate Ulcerative Colitis: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Diet. Suppl. 2019, 16, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Tu, L.; Cicuttini, F.; Han, W.; Zhu, Z.; Antony, B.; Wluka, A.; Winzenberg, T.; Meng, T.; Aitken, D.; et al. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 1634–1640.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaromytidou, E.; Koufakis, T.; Dimakopoulos, G.; Drivakou, D.; Konstantinidou, S.; Rakitzi, P.; Grammatiki, M.; Manthou, E.; Notopoulos, A.; Iakovou, I.; et al. Vitamin D Alleviates Anxiety and Depression in Elderly People with Prediabetes: A Randomized Controlled Study. Metabolites 2022, 12, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, A.; Banafshe, H.R.; Motmaen, M.; Rasouli-Azad, M.; Bahmani, F.; Asemi, Z. Clinical trial of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on psychological symptoms and metabolic profiles in maintenance methadone treatment patients. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 79, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, A.; Rasouli-Azad, M.; Farhadi, M.H.; Mirhosseini, N.; Motmaen, M.; Pishyareh, E.; Omidi, A.; Asemi, Z. Exploring the Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cognitive Functions and Mental Health Status in Subjects Under Methadone Maintenance Treatment. J. Addict. Med. 2020, 14, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Zheng, A.; Han, L. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and the role of maternal prenatal depression. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbaghmanesh, M.H.; Vaziri, F.; Najib, F.; Nasiri, S.; Pourahmad, S. The effect of vitamin D consumption during pregnancy on maternal thyroid function and depression: A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2018, in press. [CrossRef]

- Jamilian, M.; Samimi, M.; Mirhosseini, N.; Ebrahimi, F.A.; Aghadavod, E.; Talaee, R.; Jafarnejad, S.; Dizaji, S.H.; Asemi, Z. The influences of vitamin D and omega-3 co-supplementation on clinical, metabolic and genetic parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 238, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosaee, S.; Soltani, S.; Esteghamati, A.; Motevalian, S.A.; Tehrani-Doost, M.; Clark, C.C.; Jazayeri, S. Effects of zinc, vitamin D, and their co-supplementation on mood, serum cortisol, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with obesity and mild to moderate depressive symptoms: A phase II, 12-wk, 2 × 2 factorial design, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition 2020, 71, 110601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raygan, F.; Ostadmohammadi, V.; Bahmani, F.; Asemi, Z. The effects of vitamin D and probiotic co-supplementation on mental health parameters and metabolic status in type 2 diabetic patients with coronary heart disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, S.; Amani, R.; Jafarirad, S.; Cheraghian, B.; Sayyah, M.; Hemmati, A.A. The effect of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on inflammatory biomarkers, estradiol levels and severity of symptoms in women with postpartum depression: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzek, D.; Kołota, A.; Lachowicz, K.; Skolmowska, D.; Stachoń, M.; Głąbska, D. Association between Vitamin D Supplementation and Mental Health in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Mbuagbaw, L.; Samaan, Z.; Zhang, S.; Adachi, J.D.; Papaioannou, A.; Thabane, L. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in depression in adults: A systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.T.; Waterhouse, M.; Romero, B.D.; Baxter, C.; English, D.R.; Almeida, O.P.; Berk, M.; Ebeling, P.R.; Armstrong, B.K.; McLeod, D.S.A.; et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on depression in older Australian adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamanchili, V.; Gallagher, J.C. Dose ranging effects of vitamin D3 on the geriatric depression score: A clinical trial. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 178, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukri, M.A.; Conner, T.S.; Haszard, J.J.; Harper, M.J.; Houghton, L.A. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms and psychological wellbeing in healthy adult women: A double-blind randomised controlled clinical trial. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018, 7, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; de Dieu Tapsoba, J.; Duggan, C.; Wang, C.Y.; Korde, L.; McTiernan, A. Repletion of vitamin D associated with deterioration of sleep quality among postmenopausal women. Prev. Med. 2016, 93, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorde, R.; Kubiak, J. No improvement in depressive symptoms by vitamin D supplementation: Results from a randomised controlled trial. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018, 7, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, E.J.; Lips, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.; Elders, P.J.; Heijboer, A.C.; Heijer, M.D.; Bet, P.M.; van Marwijk, H.W.; van Schoor, N.M. Vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of depression and poor physical function in older persons: The D-Vitaal study, a randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lian, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, H.; Li, G. Efficacy of High-Dose Supplementation with Oral Vitamin D3 on Depressive Symptoms in Dialysis Patients with Vitamin D3 Insufficiency: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 36, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolf, L.; Muris, A.-H.; Bol, Y.; Damoiseaux, J.; Smolders, J.; Hupperts, R. Vitamin D 3 supplementation in multiple sclerosis: Symptoms and biomarkers of depression. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 378, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, T. Vitamin D3 as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of depression in tuberculosis patients: A short-term pilot randomized double-blind controlled study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 3103–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzavandi, F.; Babaie, S.; Rahimpour, S.; Razmpoosh, E.; Talenezhad, N.; Zarch, S.M.A.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H. The effect of high dose of intramuscular vitamin D supplement injections on depression in patients with type 2 diabetes and vitamin D deficiency: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Obes. Med. 2020, 17, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereke, O.I.; Reynolds, C.F.; Mischoulon, D.; Chang, G.; Vyas, C.M.; Cook, N.R.; Weinberg, A.; Bubes, V.; Copeland, T.; Friedenberg, G.; et al. Effect of Long-term Vitamin D3 Supplementation vs Placebo on Risk of Depression or Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms and on Change in Mood Scores. JAMA 2020, 324, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spedding, S. Vitamin D and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing studies with and without biological flaws. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1501–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.A.; Edmondson, D.; Wasson, L.T.; Falzon, L.P.; Homma, K.B.; Ezeokoli, N.; Li, P.B.; Davidson, K.W. Vitamin D supplementation for depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom. Med. 2014, 76, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Huang, T.; Lou, D.; Fu, R.; Ni, C.; Hong, J.; Ruan, L. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on the incidence and prognosis of depression: An updated meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 903547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, W. The effect of vitamin D supplement on negative emotions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year | Design of Study | Study Population (N) | Age (Years) | Depression Assessment Scale | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brouwer-Brolsma et al., 2016 | Cross-sectional | Dutch older adults (2839) | ≥65 | GDS | The study confirmed the presence of an inverse correlation between serum vitamin D levels and the severity of depressive symptoms. | [66] |

| Chan et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional | Community-dwelling Chinese men (939) | >65 | GDS | At the beginning of the study, a negative correlation was identified between the level of the vitamin D metabolite and depression. | [72] |

| Goltz et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional | Adults from general population (3926) | 20–79 | PHQ-9 | Serum 25(OH)D concentration was negatively associated with depression and obesity. | [62] |

| Hollinshead et al., 2024 | Cross-sectional | Pregnant women, postpartum women, non-pregnant/postpartum women, and men (11,337) | 20–44 | PHQ-9 | The study highlighted the presence of an inverse relationship between depressive symptomatology and vitamin D levels. | [71] |

| Hoogendijk et al., 2008 | Large population-based study | Community-dwelling older people (1282) | 65–95 | CES-D | The study revealed a strong association of lower serum 25(OH)D levels and higher PTH levels with both the presence and severity of depression. | [65] |

| Imai et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional | Community-dwelling older people living in Iceland (5006) | 66–96 | GDS-15; DSM-IV | Low serum 25(OH)D levels were modestly associated with higher depressive symptom scores. | [73] |

| Jaddou et al., 2012 | Cross-sectional | Jordanian adults (4002) | ≥25 | DASS21 | The study highlighted an inverse association between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and the prevalence of depression. | [59] |

| Jovanova et. al., 2017 | Cross-sectional | Older adults (3251) | ≥55 | CES-D | The study highlighted the presence of an inverse relationship between the level of the vitamin D metabolite and depressive symptoms, from a cross-sectional perspective. | [74] |

| Jääskeläinen et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional | Finnish men and women from the Health 2000 Survey (5371) | 30–79 | BDI | The risk of depression was negatively associated with vitamin D concentration. | [57] |

| Kamalzadeh et al., 2021 | Comparative observational study | Obese individuals with depression (174) and without depression (173) | 18–60 | DSM-V | The results suggested the presence of a negative relationship between vitamin D levels and the incidence of depression in obese individuals. | [42] |

| Lee et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional | Middle-aged and older men (3369) | 40–79 | BDI-II | The study highlighted an association between low serum 25(OH)D levels and depression, a relationship that persisted even after controlling for certain covariates. | [60] |

| Mizoue et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional | Healthy Japanese workers (1786) | 19–69 | CES-D | The results showed that subjects with low vitamin D levels exhibited an increased likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms. | [58] |

| Okasha et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | Patients with MDD (20), patients with schizophrenia (20), and healthy control subjects (20) | 20–50 | SCID-I | Patients diagnosed with MDD and schizophrenia exhibited low concentrations of 25(OH)D. | [55] |

| Pu et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional | Rheumatoid arthritis patients (161) | 25–75 | HAMD; HAMA | Lower serum concentrations of the vitamin D metabolite were identified in subjects with depression or anxiety. | [67] |

| Sherchand et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional | Adults residing in eastern Nepal (300) | ≥18 | BDI-Ia (validated Nepali version) | The results identified the presence of an inverse relationship between vitamin D deficiency and the likelihood of clinically significant depression. | [56] |

| Stewart et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional | Older people who had participated in the 2005 Health Survey for England (2070) | ≥65 | GDS | The study highlighted a negative relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and late-life depression. | [64] |

| Stokes et al., 2016 | Cross-sectional | CLD patients (111) | 20–81 | BDI-II | A negative relationship was observed between the severity of depressive symptoms and serum vitamin D levels. | [68] |

| Vidgren et al., 2018 | Cross-sectional | General middle-aged or older population (1602) | 53–73 | DSM-III | The study highlighted the presence of an inverse relationship between serum vitamin D levels and the prevalence of depression in older adults. | [29] |

| Zhu et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional | Patients with MDD (50) | 18–60 | HAMD; HAMA | The study suggested that low serum concentration of 25(OH)D is associated with increased severity of depressive symptoms, a relationship influenced by the TIV. | [17] |

| Zhu et al., 2022 | Cross-sectional | MDD patients (122) and healthy controls (119) | 21–62 | HAMD; HAMA | The results provide evidence supporting a potential link between vitamin D deficiency, alterations in functional brain network connectivity, and clinical symptoms in individuals diagnosed with MDD. | [61] |

| First Author, Year | Study Population (N) | Age (Years) | Depression Assessment Scale | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husemoen et al., 2016 | Adult general Danish population (5308) | 18–64 | SCL-90-R | No association between 25(OH)D concentrations and symptoms/diagnosis of depression and anxiety was found. | [79] |

| Mousa et al., 2018 | Overweight or obese and vitamin D-deficient adults (63) | 18–60 | BDI | The study did not show a relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and depression. | [77] |

| Pan et al., 2009 | Middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals (3262) | 50–70 | CES-D | No association was found between serum vitamin D levels and depression in middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals. | [76] |

| Yalamanchili et al., 2012 | Older postmenopausal women (489) | 65–77 | GDS-Long Form 30 | At baseline, depression was not associated with insufficient serum 25(OH)D levels. | [78] |

| Zhao et al., 2010 | US adults (3916) | ≥20 | PHQ-9 | The study indicated that no significant associations were found between serum concentrations of 25(OH)D and the presence of moderate-to-severe, major, or minor depression. | [75] |

| First Author, Year | Design of Study | Study Population (N) | Age (Years) | Follow-up (Years) | Depression Assessment Scale | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Briggs et al., 2019 | Longitudinal study | Nondepressed community-dwelling older people (3565) | ≥50 | 4 | CES-D | This study highlighted that hypovitaminosis D was associated with a 75% increased risk of developing depression over a four-year period. | [81] |

| May et al., 2010 | Cohort study | Patients with a CV diagnosis (7358) | ≥50 | 1.07 ± 1.13 (maximum 6.64) | ICD-9 | The study highlighted a negative relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and the incidence of depression in a sample of subjects without a prior history of depression. | [41] |

| Milaneschi et al., 2010 | Cohort study | Older adults (954) | ≥65 | 6 | CES-D | Participants who had low levels of 25(OH)D at the beginning of the study experienced a more significant rise in depressive symptoms over the subsequent six years. | [80] |

| Milaneschi et al., 2014 | Cohort study | Participants from the NESDA with current (1102) or remitted (790) depressive disorder and healthy controls (494) | 18–65 | 2 | DSM-IV; IDS | A negative relationship was observed between the presence and severity of depressive symptoms and serum vitamin D levels. | [51] |

| First Author, Year | Design of Study | Study Population (N) | Age (Years) | Follow-Up (Years) | Depression Assessment Scale | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berg et al., 2021 | Prospective cohort study | Older patients with depression (232) | 60–93 | 2 | DSM-IV; IDS-SR | Over a period of two years, no independent association between serum 25(OH)D levels and the course of depression was found. | [82] |

| Chan et al., 2011 | Cohort study | Community-dwelling Chinese men (629) | >65 | 4 | GDS | Serum 25(OH)D concentration had no association with the incidence of depression at 4 years. | [72] |

| Jovanova et. al., 2017 | Cohort study | Older adults (3251) | ≥55 | 10 | CES-D | No association was found between low vitamin D levels and changes in depressive symptomatology or the incidence of depression. | [74] |

| First Author, Year (Ref.) | Study Design | Study Participants, Age (Years) | Sample Size | Intervention | Follow-up Duration | Depression Assessment Scale | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Placebo | |||||||

| Abiri et al., 2022 [5] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Obese women with mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms, 20–45 | Group 1: 27 Group 2: 27 Group 3: 27 | Group 4: 27 | Group 1: 50,000 IU vitamin D soft gel/wk + 250 mg magnesium tablet/day Group 2: 50,000 IU vitamin D soft gel/wk + magnesium placebo/day Group 3: vitamin D placebo/wk + 250 mg magnesium tablet/day Group 4: vitamin D placebo/wk + magnesium placebo/day | 8 wks | BDI-II | Positive effects on depressive symptoms were found in vitamin D plus magnesium supplementation. |

| Alavi et al., 2019 [88] | Randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Older adults with moderate-to-severe depression, ≥ 60 | 39 | 39 | 50,000 IU vitamin D3/wk + TAU or placebo + TAU | 8 wks | GDS-15 | The severity of depression symptoms improved after vitamin D supplementation. |

| Alghamdi et al., 2020 [49] | Randomised clinical trial | Male and female patients diagnosed with MDD, 18–65 | 49 | 13 | 50,000 IU vitamin D3/wk + SOC or SOC | 3 months | BDI | Female patients showed a more significant improvement compared to male patients in their depressive symptoms. |

| Amini et al., 2022 [104] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Women with PPD, 18–45 | Group 1: 27 Group 2: 27 | Group 3: 27 | Group 1: 50,000 IU vitamin D3 fortnightly + 500 mg calcium carbonate daily Group 2: 50,000 IU vitamin D3 fortnightly + placebo of calcium daily Group 3: Placebo of vitamin D3 fortnightly + placebo of calcium daily | 8 wks | EPDS | Vitamin D supplementation highlighted an increase in serum 25(OH)D concentration, which improved PPD symptoms. |

| Dabbaghmanesh et al., 2019 [100] | Randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Nulliparous and multiparous females, ≥ 18 | 46 | 52 | 2000 IU vitamin D3 daily or placebo | 26th to 28th week of gestation until birth | EPDS | Vitamin D supplementation in late pregnancy may result in a substantial change in postnatal depression at the fourth week. |

| Ghaderi et al., 2017 [97] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | MMT patients, 25–70 | 34 | 34 | 50,000 IU vitamin D/2 wks or placebo | 12 wks | BDI; PSQI; BAI | Salutary effects on psychological symptoms were found in MMT patients after vitamin D supplementation. |

| Ghaderi et al., 2020 [98] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | MMT patients, 18–60 | 32 | 32 | 50,000 IU vitamin D/2 wks or placebo | 24 wks | BDI; BAI | Improvements in cognitive function and some mental health parameters were observed after vitamin D supplementation in MMT patients. |

| Jamilian et al., 2018 [101] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Women with polycystic ovary syndrome, 18–40 | 30 | 30 | 50,000 IU vitamin D/2 wks + 2000 mg/day omega-3 fatty acid from fish oil or placebo | 12 wks | BDI; DASS; GHQ-28 | Mental health parameters improved following vitamin D plus omega-3 fatty acid supplementation. |

| Kaviani et al., 2020 [85] | Double-blind, randomised clinical trial | Patients with mild-to-moderate depression, 18–60 | 28 | 28 | 50,000 IU cholecalciferol/2 wks or placebo | 8 wks | BDI-II | An increased concentration of 25(OH)D led to a decrease in depression severity in patients diagnosed with mild-to-moderate depression after vitamin D supplementation. |

| Kaviani et al., 2022 [12] | Double-blind, randomised clinical trial | Patients with mild-to-moderate depression, 18–60 | 28 | 28 | 50,000 IU cholecalciferol/2 wks or placebo | 8 wks | BDI-II | Individuals diagnosed with mild-to-moderate depression exhibited a substantial decrease in BDI-II scores after vitamin D supplementation. |

| Khoraminya et al., 2013 [89] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Patients with a diagnosis of MDD, 18–65 | 20 | 20 | Daily 1500 IU vitamin D3 + 20 mg fluoxetine or vitamin D placebo + 20 mg fluoxetine | 8 wks | HDRS; BDI | Co-administration of vitamin D and fluoxetine demonstrated superior effects compared to fluoxetine alone from the fourth week of treatment. |

| Lv et al., 2024 [99] | Retrospective, observational study | Pregnant women diagnosed with vitamin D deficiency at 12–14 weeks of gestation; 28–34 | 1365 | - | 800 IU daily from 14 weeks onwards | 14 wks onwards until gestational week 39 (38, 39) prior to delivery | HDRS; SDS; EPDS | Pregnant women in the 12–14 weeks gestational period with vitamin D deficiency had insufficient levels of vitamin D, and showed an improvement in depressive symptoms following supplementation. |

| Mozaffari-Khosravi et al., 2013 [86] | Randomised clinical trial | Depressed patients with vitamin D deficiency; 20–60 | Group 1: 40 Group 2: 40 | Group 3: 40 | Group 1: 300,000 IU of vitamin D intramuscularly Group 2: 150,000 IU of vitamin D intramuscularly Group 3: received nothing | 3 months | BDI-II | Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent among patients with depression, and restoring its levels leads to an improvement in depressive symptoms. Higher doses, such as 300,000 IU compared to 150,000 IU, are more efficient and also safe. |

| Narula et al., 2017 [93] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Patients with a prior diagnosis of CD in remission, 18–70 | Group 1: 18 Group 2: 16 | - | Group 1: 10,000 IU vitamin D3/day Group 2: 1000 IU vitamin D3/day | 12 months | HADS | Both doses indicated mood improvement, with the higher dose exhibiting potential in normalising mood symptoms in patients suffering from clinical anxiety and depression. |

| Omidian et al., 2019 [90] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | T2DM patients with mild-to-moderate depression, 30–60 | 32 | 34 | 4000 IU vitamin D/day or placebo | 12 wks | Persian version of BDI-II | Patients with T2DM and depression showed reduced depressive symptoms after vitamin D supplementation. |

| Penckofer et al., 2017 [91] | Open-label, proof-of-concept study | Women with T2DM and significant depressive symptoms, ≥ 18 | 50 | - | 50,000 IU ergocalciferol/wk | 6 months | CES-D; PHQ-9; STAI; SF-12 | Reduced depressive symptoms were emphasised following vitamin D2 supplementation in women with T2DM. |

| Raygan et al., 2018 [103] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Diabetic people with CHD, 45–85 | 30 | 30 | 50,000 IU vitamin D3 every 2 wks plus 8 × 109 CFU/g probiotic or placebo | 12 wks | BDI; BAI; GHQ-28 | Mental health parameters were considerably enhanced in diabetic patients with CHD following co-supplementation with vitamin D and probiotics. |

| Sharifi et al., 2019 [94] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Patients with mild-to-moderate UC, vitamin D group: 37.5 ± 9.0; placebo group: 35.0 ± 9.2 | 46 | 40 | One muscular injection of 1 mL 300,000 IU vitamin D3 or 1 mL normal saline as placebo | 3 months | BDI-II | Mild-to-moderate UC patients receiving 300,000 IU vitamin D3 showed a major reduction in BDI-II scores after 3 months. |

| Sikaroudi et al., 2020 [35] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Male and female patients with IBS-D and insufficient vitamin D levels, 18–65 | 39 | 35 | 50,000 IU vitamin D3/wk or placebo | 9 wks | HADS | Considerable differences were observed between the groups, with patients receiving vitamin D showing a decrease in depressive symptoms. |

| Stokes et al., 2016 [68] | Interventional study | Patients with CLD and inadequate vitamin D concentrations, 20–81 | 77 | - | 20,000 IU vitamin D3 daily for the first seven days, then weekly thereon | 6 months | BDI-II | Normalisation of vitamin D levels improved depressive symptoms in patients diagnosed with CLD. |

| Vaziri et al., 2016 [16] | Randomised clinical trial | Pregnant women with a baseline depression score of 0 to 13, 18–39 | 78 | 75 | 2000 IU vitamin D3/day or placebo | From 26 to 28 wks of gestation until childbirth | EPDS | Daily vitamin D3 supplementation, from 26 to 28 weeks of gestation until childbirth, indicated a decrease in perinatal depression levels. |

| Vellekkatt et al., 2020 [87] | Double-blind, randomised, parallel-arm, placebo-controlled trial | Patients with MDD and concurrent vitamin D deficiency, 18–65 | 23 | 23 | TAU + single parenteral dose of 300,000 IU of cholecalciferol or TAU + placebo | 12 wks | HDRS-17; QLES; CGI-S | A higher, single-administration dose of 300,000 IU of vitamin D was proven to be efficient in treating MDD and showed improvement in short-term quality of life. |

| Yosaee et al., 2020 [102] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Obese/overweight patients with depressive symptoms, > 20 | Group 1: 27 Group 2: 24 Group 3: 25 | Group 4: 22 | Group 1: 2000 IU/day vitamin D3 + daily placebo for zinc Group 2: 30 mg/day zinc gluconate + daily placebo for vitamin D Group 3: 2000 IU/day vitamin D3 + 30 mg/day zinc gluconate Group 4: vitamin D placebo + zinc placebo | 12 wks | BDI-II | Obese and overweight patients with depressive symptoms showed a significant decrease in BDI-II scores after administration of vitamin D, zinc, and both concurrently. |

| Zaromytidou et al., 2022 [96] | Randomised controlled study | Elderly people with prediabetes, > 60 | 45 | 45 | 25,000 IU vitamin D3/wk or nothing | 12 months | PHQ-9: STAI | Relieved symptoms of anxiety and depression were observed in a high-risk population after vitamin D dosing. |

| Zheng et al., 2019 [95] | Double-blind, randomised, parallel-arm, placebo-controlled trial | Patients with knee OA and vitamin D deficiency, vitamin D group: 63.5; placebo group: 62.9 | 209 | 204 | 50,000 IU vitamin D3/month or placebo | 24 months | PHQ-9 | Depressive patients diagnosed with knee OA whose vitamin D levels were sustained through supplementation demonstrated positive effects on depressive symptoms. |

| Zhou et al., 2024 [92] | Prospective study | Patients with DPN and vitamin D insufficiency, ≥ 60 | 158 | - | 5000 IU vitamin D daily | 12 wks | HAMD-17 | The study results highlighted the beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation in patients with DPN and vitamin D insufficiency. |

| First Author, Year (Ref.) | Study Design | Study Participants, Age (Years) | Sample Size | Intervention | Follow-up Duration | Depression Assessment scale | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Placebo | |||||||

| Choukri et al., 2018 [109] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Healthy women, 18–40 | 76 | 76 | 50,000 IU vitamin D3/month or placebo | 6 months | CES-D; HADS; Flourishing Scale | Depression and other mood outcomes in healthy premenopausal women were not positively influenced by vitamin D supplementation. |

| Hansen et al., 2019 [11] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Patients diagnosed with mild-to-severe depression, 18–65 | 28 | 34 | 70 µg (2800 IU) vitamin D3/day + TAU or placebo + TAU | 6 months | HAMD-17 | Symptom severity did not show any decline in patients with depression following vitamin D supplementation. |

| Jorde et al., 2018 [111] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Subjects recruited from the Tromsø Study (a population-based health survey in the municipality of Tromsø), ≥ 40 | 206 | 202 | 100,000 IU vitamin D as bolus dose, followed by 20,000 IU vitamin D/wk or placebo | 4 months | BDI-II | The results of the study highlighted no effects of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms. |

| Koning et al., 2019 [112] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | An older population with a low vitamin D status and clinically relevant depressive symptoms, 60–80 | 77 | 78 | Daily dose of 1200 IU vitamin D3 or placebo | 12 months | CES-D | No impact on depressive symptoms was observed after vitamin D supplementation. |

| Marsh et al., 2017 [22] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder (currently experiencing depressive symptoms) and vitamin D deficiency, 18–70 | 16 | 17 | 5000 IU vitamin D3/day or placebo | 12 wks | MADRS; HAM-A; YMRS | High levels of 25(OH)D, compared to a placebo, did not lead to any improvement in depressive symptoms. |

| Mason et al., 2016 [110] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Overweight postmenopausal women, 50–75 | 109 | 109 | Weight loss + 2000 IU vitamin D3/day or weight loss + daily placebo | 12 months | BSI; PQSI | Vitamin D supplementation, compared to a placebo, did not have an impact on depressive symptoms. |

| Mirzavandi et al., 2020 [116] | Randomised clinical trial | Patients with T2DM and vitamin D deficiency, 30–60 | 25 | 25 | 200,000 IU of vitamin D injection at week 0 and week 4 of study or nothing | 8 wks | Beck depression test | Supplemented high levels of serum 25(OH)D had no effect on the Beck depression score. |

| Mousa et al., 2018 [77] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Overweight or obese and vitamin D-deficient adults, 18–60 | 26 | 22 | Bolus oral dose of 100,000 IU followed by 4000 IU daily of cholecalciferol or placebo | 16 wks | BDI | No noticeable differences were observed in the total BDI scores between patients supplemented with vitamin D and those in the placebo group. |

| Okereke et al., 2020 [117] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial | Men and women in the VITAL-DEP, ≥ 50 | 9181 | 9172 | 2000 IU of cholecalciferol/day and fish oil (Omacor; 1 g/day capsule containing 840 mg of omega-3 fatty acids as 465 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and 375 mg of docosahexaenoic acid) or placebo | 5.3 years | PHQ-8 | Patients who received vitamin D supplementation compared to a placebo exhibited no major differences in the incidence and recurrence of depression. |

| Rahman et al., 2023 [107] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Older Australian adults, 60–84 | 10,662 | 10,653 | 60,000 IU vitamin D3/month or placebo | 5 years | PHQ-9 | This analysis did not find an overall improvement in depressive symptoms following monthly vitamin D supplementation. |

| Rolf et al., 2017 [114] | Randomised, placebo-controlled trial | MS patients, 18–55 | 20 | 20 | 7000 IU cholecalciferol/day in first 4 weeks, followed by 14,000 IU cholecalciferol/day up to week 48 or placebo | 48 wks | HADS-D; FSS | High doses of vitamin D supplementation show no decline in depressive symptoms. |

| Wang et al., 2016 [113] | Prospective, randomised, double-blind trial | Dialysis patients with depressive symptoms and vitamin D insufficiency, ≥ 18 | 362 | 364 | 50,000 IU vitamin D3/wk or placebo | 52 wks | Chinese version of BDI-II | No beneficial effect on depressive symptoms was observed after vitamin D supplementation in dialysis patients. |

| Yalamanchili et al., 2012 [78] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Older postmenopausal women, 65–77 | Group 1: 120 Group 2: 123 Group 3: 122 | Group 4: 123 | Group 1: HT (oestrogens 0.625 mg/daily in hysterectomized women or combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg/daily in women with intact uterus) Group 2: calcitriol 0.25 g BID Group 3: HT + calcitriol Group 4: matching placebo | 3 years | GDS-Long form 30 | No significant effect was observed after HT, calcitriol, or their co-administration in older postmenopausal women. |

| Yalamanchili et al., 2018 [108] | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Older Caucasian and African American women from Gallagher et al. [45,50], 57–90 | Group 1: 22 (20 Caucasian, 2 Afro-American) Group 2: 45 (21 Caucasian, 24 Afro-American) Group 3: 43 (20 Caucasian, 23 Afro-American) Group 4: 44 (21 Caucasian, 23 Afro-American) Group 5: 23 (20 Caucasian, 3 Afro-American) Group 6: 24 (20 Caucasian, 4 Afro-American) Group 7: 34 (20 Caucasian, 14 Afro-American) | Group 8: 38 (21 Caucasian, 17 Afro-American) | Group 1: 400 IU of vitamin D3/day Group 2: 800 IU of vitamin D3/day Group 3: 1600 IU of vitamin D3/day Group 4: 2400 IU of vitamin D3/day Group 5: 3200 IU of vitamin D3/day Group 6: 4000 IU of vitamin D3/day Group 7: 4800 IU of vitamin D3/day Group 8: placebo | 12 months | GDS | Depression scores were not positively influenced in older Caucasian and African American women following vitamin D supplementation. |

| Zhang et al., 2018 [115] | Randomised, double-blind clinical trial | PTB patients with depression, ≥ 18 | 56 | 64 | Bolus oral dose of 100,000 IU cholecalciferol/wk or placebo | 8 wks | BDI-II | No significant effect on BDI-II scores was highlighted following vitamin D supplementation in PTB patients with depression. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roșian, A.; Zdrîncă, M.; Dobjanschi, L.; Vicaș, L.G.; Mureșan, M.E.; Dindelegan, C.M.; Platona, R.I.; Marian, E. The Role of Vitamin D in the Management of Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18060792

Roșian A, Zdrîncă M, Dobjanschi L, Vicaș LG, Mureșan ME, Dindelegan CM, Platona RI, Marian E. The Role of Vitamin D in the Management of Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(6):792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18060792

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoșian, Andreea, Mihaela Zdrîncă, Luciana Dobjanschi, Laura Grațiela Vicaș, Mariana Eugenia Mureșan, Camelia Maria Dindelegan, Rita Ioana Platona, and Eleonora Marian. 2025. "The Role of Vitamin D in the Management of Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 6: 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18060792

APA StyleRoșian, A., Zdrîncă, M., Dobjanschi, L., Vicaș, L. G., Mureșan, M. E., Dindelegan, C. M., Platona, R. I., & Marian, E. (2025). The Role of Vitamin D in the Management of Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals, 18(6), 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18060792