1. Introduction

Epileptic encephalopathies are severe forms of epilepsy which typically occur early in infancy and result in reduced cognitive function [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These disorders can be part of epileptic syndromes and can be characterized by generalized or recurrent focal seizures and being severe and usually refractory to standard antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including benzodiazepines, phenobarbital, sodium valproate, lamotrigine, and topiramate.

Dravet syndrome (DS) and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) are two rare but very severe epileptic syndromes [

5]. DS, also known as severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI), is a genetic condition caused frequently by the loss-of-function of

SCN1A variants, which typically develops in the first year of a life with frequent, prolonged seizures commonly triggered by hyperthermia [

6,

7,

8]. LGS is a severe form of epilepsy, characterized by multiple types of seizures (tonic axial, atonic, absence, myoclonic, and generalized tonic–clonic seizures) and intellectual disability [

9]. It can be associated with encephalitis, meningitis, tuberous sclerosis, brain malformations, and brain injury. Even in this case, treatment with AEDs is often ineffective.

Patients with DS and LGS are usually in polypharmacy, treated with a median of three AEDs [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

The use of these drugs should be optimized to reduce the burden of seizures, as well as to minimize adverse events (AEs).

Valproate (VPA) is recognized as the first-line medication [

11,

16]; for subsequent lines, various AEDs have been approved as adjunctive therapies.

Among the pharmacological agents approved in the European Union as adjunctive therapy for the management of pediatric epilepsy-related seizures, in particular for DS, we can find stiripentol, cannabidiol, and fenfluramine.

In 2007, stiripentol (Diacomit

®) received approval in Europe as an orphan drug for managing bilateral tonic–clonic seizures (BTCS) in children with DS [

17]. It is intended for use as an add-on therapy alongside clobazam (CLB) and VPA, in cases where these drugs are not sufficient to control seizures [

18,

19]. Several mechanisms of action have been proposed for stiripentol, including enhanced GABAergic neurotransmission, inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase, reduction in calcium-mediated toxicity in hippocampal neurons with NMDA receptors, and the inhibition of calcium channels [

20]. Several studies have highlighted that stiripentol is a generally well-tolerated and effective medication for reducing the frequency and duration of epileptic seizures [

21,

22], with certain AEs occurring more frequently, such as weight loss, decreased appetite, and drowsiness [

23,

24].

Cannabidiol, along with Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), is one of the bioactive compounds found in the

Cannabis plant [

25]. Unlike THC, cannabidiol is not a psychoactive substance and exhibits anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and antioxidant properties [

26]. Although the exact anticonvulsant mechanism of action has not yet been fully elucidated, cannabidiol has proven effective in suppressing seizures in animal models of epilepsy [

26]. It has been proposed that cannabidiol may modulate neuronal excitability by interacting with various targets involved in the functional regulation of neuronal excitability, such as the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), the equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1), the orphan G protein-coupled receptor 55 (GPR55) [

27], the voltage-gated sodium channels [

28], the dopamine D2/D3 receptors [

29,

30], and the cannabinoid CB1 receptors [

31,

32,

33]. Cannabidiol has been approved in the European Union under the name Epidyolex

® (GW Pharma [International] B.V.), in combination with CLB, for the treatment of seizures associated with LGS and DS in patients aged two years and older [

34]. Additionally, in Europe, cannabidiol is authorized as an adjunct therapy for seizures associated with the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) in patients over the age of two [

35]. The primary AEs associated with cannabidiol use include drowsiness, diarrhea, vomiting, and pyrexia [

36,

37,

38,

39].

Fenfluramine (Fintepla

®) is an anticonvulsant drug with a dual mechanism of action, functioning both as an agonist of the serotonergic system and a positive allosteric modulator of sigma-1 receptors (σ1-Rs) [

40]. It has been suggested that its interaction with serotonin (5-HT) receptors enhances inhibitory transmission mediated by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), while the activation of σ1-Rs is predominantly associated with a reduction in excitatory glutamatergic signaling [

40]. Previously, the drug was used at high doses as an appetite suppressant in adults with obesity, but its marketing was discontinued due to an increased risk of serious cardiovascular events, valvular heart disease (VHD), and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). More recently, it has been approved in Europe at significantly lower doses for the treatment of seizures associated with DS and LGS, as an adjunctive therapy to other anticonvulsants in patients older than 2 years [

41]. Fenfluramine exhibits a favorable tolerability profile, with the most commonly reported AEs across multiple studies being reduced appetite, fatigue, and somnolence [

40,

42,

43].

Although the tolerability of these drugs has been assessed in several clinical studies, post-marketing surveillance is essential to ensure the safe use of these medications. Indeed, post-marketing studies on pharmacovigilance databases potentially enable the identification of rare or severe AEs, which may not have emerged during the drug development phase due to time constraints or limited study populations [

44].

The aim of this study was to analyze data from the Eudravigilance database to comprehensively assess the safety profile of these drugs.

2. Results

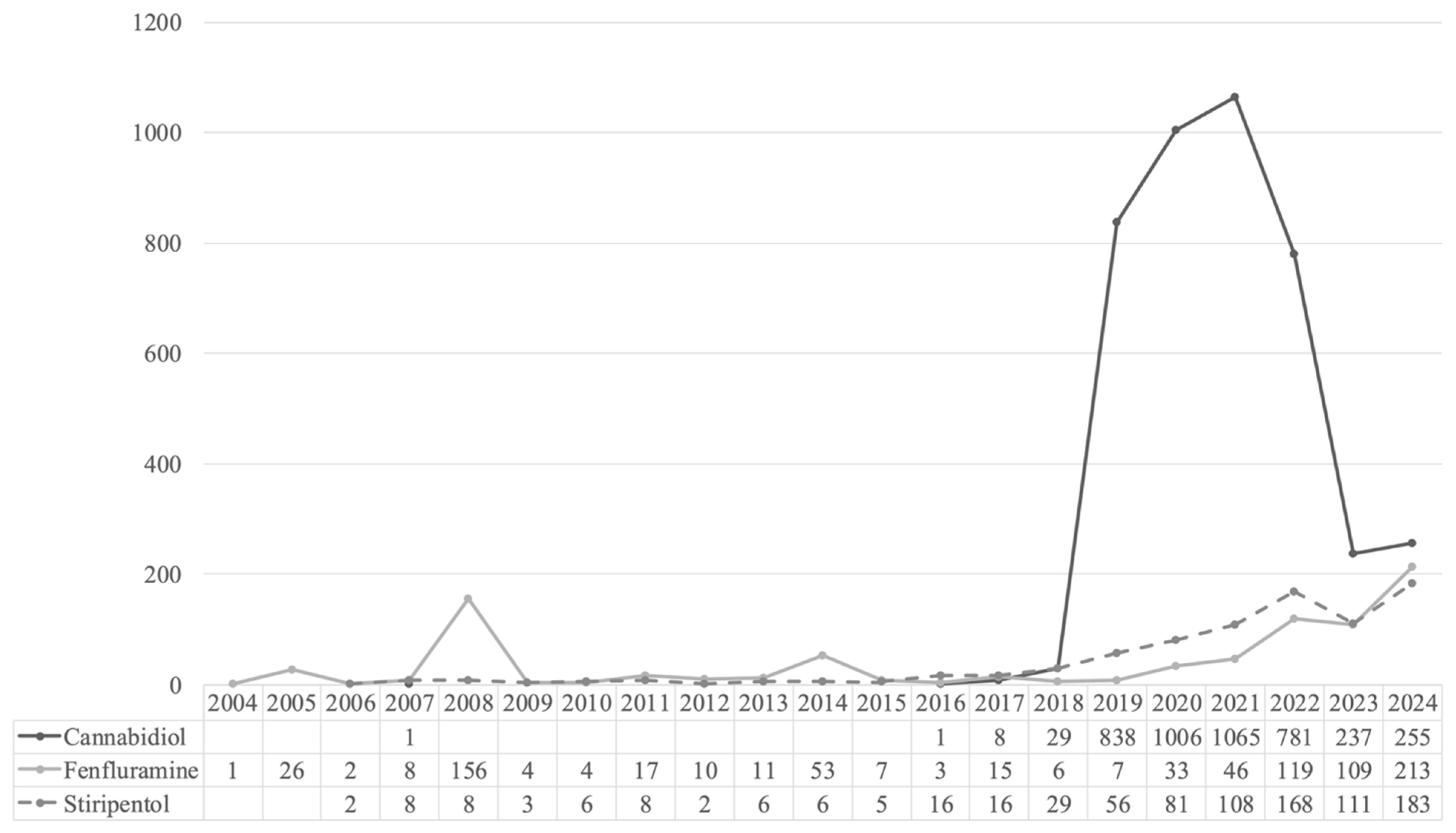

Our analysis showed a high prevalence of ICSRs from cannabidiol, followed by fenfluramine and stiripentol. Significantly higher probabilities of reporting Cardiac disorders, Vascular disorders, and Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders were observed with fenfluramine. Cannabidiol was associated with Product issues, whereas stiripentol was associated with Injury, poisoning, procedural complications, Metabolism and nutrition disorders, and Blood and lymphatic system disorders.

Overall, 5896 ICSRs related to stiripentol (

n = 822; 13.9%), cannabidiol (

n = 4222; 71.6%), and fenfluramine (

n = 852; 14.5%) were retrieved from the Eudravigilance database for the reference period (

Figure 1). The number of cases reported increased year by year, with the highest number of reports observed in 2021 for cannabidiol (

n = 1065; 25.2%), and in 2024 for fenfluramine (

n = 213; 25%) and stiripentol (

n = 183; 22.3%).

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the ICSRs for each drug.

The incidence of events in males accounted for a larger proportion than females, except for fenfluramine (stiripentol n = 423; 51.46%; cannabidiol n = 2149; 50.9%; fenfluramine n = 243; 28.52%; p < 0.001). Adult patients (≥18 years old) were more represented than the pediatric population (<18 years old), except for stiripentol.

In terms of seriousness, more than 80% of ICSRs indicated at least one ADR classifiable as serious, although less frequently in the fenfluramine group (stiripentol n = 728, 88.6%; cannabidiol n = 3619, 85.7%; fenfluramine n = 713, 83.7%; p = 0.015). The outcome recovered/resolved was reported for 2043 cases, more frequently for cannabidiol (n = 1423, 16.1%; p = 0.009), whereas a fatal event was reported for 612 cases, more frequently for cannabidiol (n = 503, 5.7%; p = 0.001). However, outcome data were available in less than 50% of ICSRs (stiripentol n = 620, 27.9%; cannabidiol n = 3566, 40.4%; fenfluramine n = 814, 39.1%).

More than 80% of ADRs were reported by healthcare professionals, apart from stiripentol (stiripentol n = 444, 54.01%; cannabidiol n = 3974, 94.13%; fenfluramine n = 692, 81.22%). Unfortunately, further information about the sender is not available. ICSRs are reported according to the sender, identified only as a healthcare or non-healthcare professional.

The largest number of AEs related to stiripentol and cannabidiol came from France (8.03% and 9.85, respectively), whereas in Germany, ICSRs associated with fenfluramine were reported more frequently (15.49%).

“Nervous system disorders” was the most represented reaction group (stiripentol

n = 563; 26.6%; cannabidiol

n = 2292; 27.1%; fenfluramine

n = 368; 19.1%;

Table 2).

The most frequent suspected reactions related to this SOC were ‘seizure’ (stiripentol

n = 423; cannabidiol

n = 1609; fenfluramine

n = 151) and ‘somnolence’ (stiripentol

n = 84; cannabidiol

n = 207; fenfluramine

n = 32) (

Table 3).

Significantly disproportionately, reporting for fenfluramine-related reports compared to the other drugs was observed for “Cardiac disorders” (ROR = 26.29; 95% CI 25.422–27.187), “Vascular disorders” (ROR = 5.271; 4.959–5.602), and “Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders” (ROR = 4.678; 4.579–4.779) (

Table 4;

Tables S1–S4). The most frequently suspected reactions related to these SOCs were pulmonary hypertension (‘pulmonary arterial hypertension’, PAH,

n = 27, and ‘pulmonary hypertension’

n = 62) and valvular heart disease (VHD), including ‘aortic valve incompetence’ (

n = 79), ‘cardiac valve disease’ (

n = 51), ‘mitral valve incompetence’ (

n = 86) ‘mitral valve stenosis’ (

n = 11), and ‘tricuspid valve incompetence’ (

n = 44;

Table 5). Moreover, significantly higher probabilities of reporting were observed for “Product issues” with cannabidiol (ROR = 5.989; 5.148–6.968), and “Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications” (ROR = 3.033; 2.998–3.068), “Metabolism and nutrition disorders” (ROR = 2.867; 22.796–2.94), and “Blood and lymphatic system disorders” (ROR = 2.64; 2.366–2.947) with stiripentol (

Table 6 and

Table 7).

3. Discussion

A lot of AEDs can be used to control seizures in epileptic syndromes in the first or subsequent lines (such as clobazam or valproate). We focused our analysis on drugs with similar clinical applications in the context of pediatric epilepsy-related seizures. Stiripentol, cannabidiol, and fenfluramine are AEDs with different mechanisms of action that have been approved for specific difficult-to-treat epileptic syndromes. We found differences in terms of incidence according to age and gender, but we cannot draw final conclusions due to the lack of detailed information on the use of these drugs. In particular, adults were more represented than pediatric patients for fenfluramine and cannabidiol. These drugs are approved for epileptic syndromes, but their use is not limited to children and even adults or the elderly can also be treated according to the summary of the products’ characteristics. Indeed, these syndromes generally develop in the first years of life and can persist into adulthood, though seizure types and frequency may change [

45,

46].

The safety profile of these drugs is quite similar, including the occurrence of some common AEs such as weight loss, decreased appetite, and drowsiness/somnolence. Nevertheless, clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance allowed us to recognize specific ADRs, such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, nausea, and vomiting for stiripentol, anemia, diarrhea, and infections for cannabidiol, and gastrointestinal and cardiovascular disorders for fenfluramine.

Many of the above ADRs are often due to the other anticonvulsants used in combination (e.g., clobazam and valproate) and may resolve with dose reduction.

Our analysis showed increased reporting frequencies of “Nervous system disorders” for the three drugs. The most frequent events were ‘seizure’ and similar reactions (‘atonic seizure’, ‘epilepsy’, ‘generalized tonic–clonic seizure’, ‘myoclonic epilepsy’, ‘partial seizure’, ‘petit mal epilepsy’, ‘seizure cluster’, ‘status epilepticus’, and ‘tonic convulsion’). Most of these ADRs can be derived from insufficient therapeutic control of pre-existing diseases rather than from exposure to the drug. However, seizure aggravation (or the development of new types of seizures) can occur, in theory, with all AEDs [

47]. The mechanisms of this paradoxical effect are mostly unknown and may be related to specific pharmacodynamic mechanisms, e.g., enhanced GABA transmission or the blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels [

48].

The SmPC of fenfluramine describes a possible clinically relevant increase in seizure frequency, which may occur during treatment and may require dose adjustment or discontinuation, as with other AEDs [

41]. Indeed, seizure was among the most frequent AEs leading to study withdrawal in clinical trials and status epilepticus was observed in three patients (3%) treated with the highest dose of fenfluramine [

49].

Even for cannabidiol, a clinically relevant increase in seizure frequency may occur during treatment, but the frequency of status epilepticus in the phase 3 clinical trials was similar to that of the placebo [

35].

To the best of our knowledge, stiripentol seems to not be associated with paradoxical seizures [

17], and the reaction ‘seizure’ is not reported in its SmPC. Therefore, our findings should be further explored to figure out the link between the events that are more frequently reported on the Eudravigilance database and treatment with stiripentol.

As expected, ‘somnolence’ was the second most reported neurological event, being already recognized as a ‘very common’ ADR in the three SmPCs.

According to the disproportionality analysis, the most significant signals at the SOC level were “Cardiac disorders”, “Vascular disorders”, and “Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders” for fenfluramine compared to the other drugs.

These results are in accordance with the known safety profile of fenfluramine used as an anorectic agent. The drug was approved for adults to reduce body weight, but it was withdrawn in 1997 based on the increased risk of VHD and PAH, even if most of the cardiopulmonary disorders improved following drug discontinuation [

50,

51]. In these patients, fenfluramine was prescribed at higher dosages (>40–60 mg daily or 0.5–2.1 mg/kg/day) than those approved for epileptic syndromes, ranging from 0.2 mg/kg/day–0.7 mg/kg/day, with a maximal recommended daily dose of 17–26 mg [

48,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. No cases of VHD or PAH were observed during the studies for epileptic syndromes. These results have been confirmed in long-term studies in patients treated for 3 years. These data support the cardiovascular safety of fenfluramine at lower dosages used for seizures compared to the higher dosages used for obesity [

49,

63,

64]. However, post-marketing data showed that VHD and PAH can also occur with low doses of fenfluramine and cardiac monitoring using echocardiography is recommended prior to starting treatment to exclude any pre-existing diseases: every 6 months for the first 2 years and annually thereafter [

41]. In the case of pathological abnormalities on the echocardiogram, it is recommended to evaluate the benefit of continuing treatment compared to the risk of ADRs.

To confirm that these ADRs were related to the use of fenfluramine for epilepsy, we selected the ICSRs from the year of approval for epileptic syndromes (2020), and we found a considerable reduction in the number of events (

Table 5). However, this does not exclude the risk of VHD and PAH and patients should continue to be monitored.

The pathophysiology of these side effects is still under debate but may be linked to the interaction with serotonin receptors and the consequent growth of pulmonary smooth muscle cells [

65,

66]. Moreover, 5HT2B receptors can be specifically involved with the hyperplasia responsible for VHD [

67].

Currently, these events are listed in the SmPC of fenfluramine with a frequency ‘not known’ [

41], and further investigations are thus needed to define the burden of this association.

Significantly higher probabilities of reporting “Product issues” were observed with cannabidiol, in particular ‘product supply issue’ and ‘product distribution issue’. These events were observed only with cannabidiol and were reported for more than 85% of countries from the Non-European Economic Area (

Table S5). As far as we know, these issues have not been raised previously, and we can only speculate that they may be related to the nature of the product as a cannabis-derived drug.

Finally, we found a significant association for stiripentol with the onset of “Blood and lymphatic system disorders”, “Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications”, and “Metabolism and nutrition disorders”.

Neutropenia is a common AE associated with the administration of stiripentol, and blood counts should be assessed prior to starting treatment, and then monitored every 6 months [

17]. Instead, thrombocytopenia has been recognized as a rare event.

As regards to “Metabolism and nutrition disorders”, it is well known that decreased appetite represents an expected event in patients treated with stiripentol, but also with fenfluramine and cannabidiol, as reported in their SmPCs [

17,

35,

41]. This represents a critical point, especially for the pediatric population, which may experience growth retardation given the frequency of gastrointestinal ADRs (nausea and vomiting). Therefore, the growth rate of children under these treatments should be carefully monitored.

Finally, ‘product use in unapproved indication’ (e.g., LGS, frontal lobe epilepsy, epileptic encephalopathy, partial seizures, febrile convulsion, and idiopathic generalized epilepsy) was the most reported ADR in the group “Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications”, supported by data emerging regarding off-label use in other forms of epilepsy. Indeed, stiripentol demonstrated to be effective in different seizure types for pediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, apart from DS [

18,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75].

Although our findings provide a comprehensive perspective in the evaluation of ADRs related to the drugs under evaluation, the results of the present study should be observed in the light of some limitations, including the lack of detailed information about the treatment, the number of patients effectively treated in the reference period, the specific patients’ characteristics, the presence of multiple suspected drugs in ICSRs, the risk of under-reporting compared to the global clinical population, and the difficulty in identifying confounders. Indeed, at this access level, detailed information about drug use is not available. In particular, treatment duration was available only for a small percentage of ICSRs (8–13%). Therefore, it is difficult to conduct further analyses or construct hypotheses. Moreover, even when this information is available, is not possible to figure out if the treatment began in pediatric age, because we only have the treatment duration and the onset age of ADRs., e.g., for an ICSR, we know that the patient experienced the ADR at the age 18–64 years and that cannabidiol was used for 500 days, but we do not know the exact age and when cannabidiol was started.