Discovery of Novel Piperidinyl-Based Benzoxazole Derivatives as Anticancer Agents Targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met Kinases

Abstract

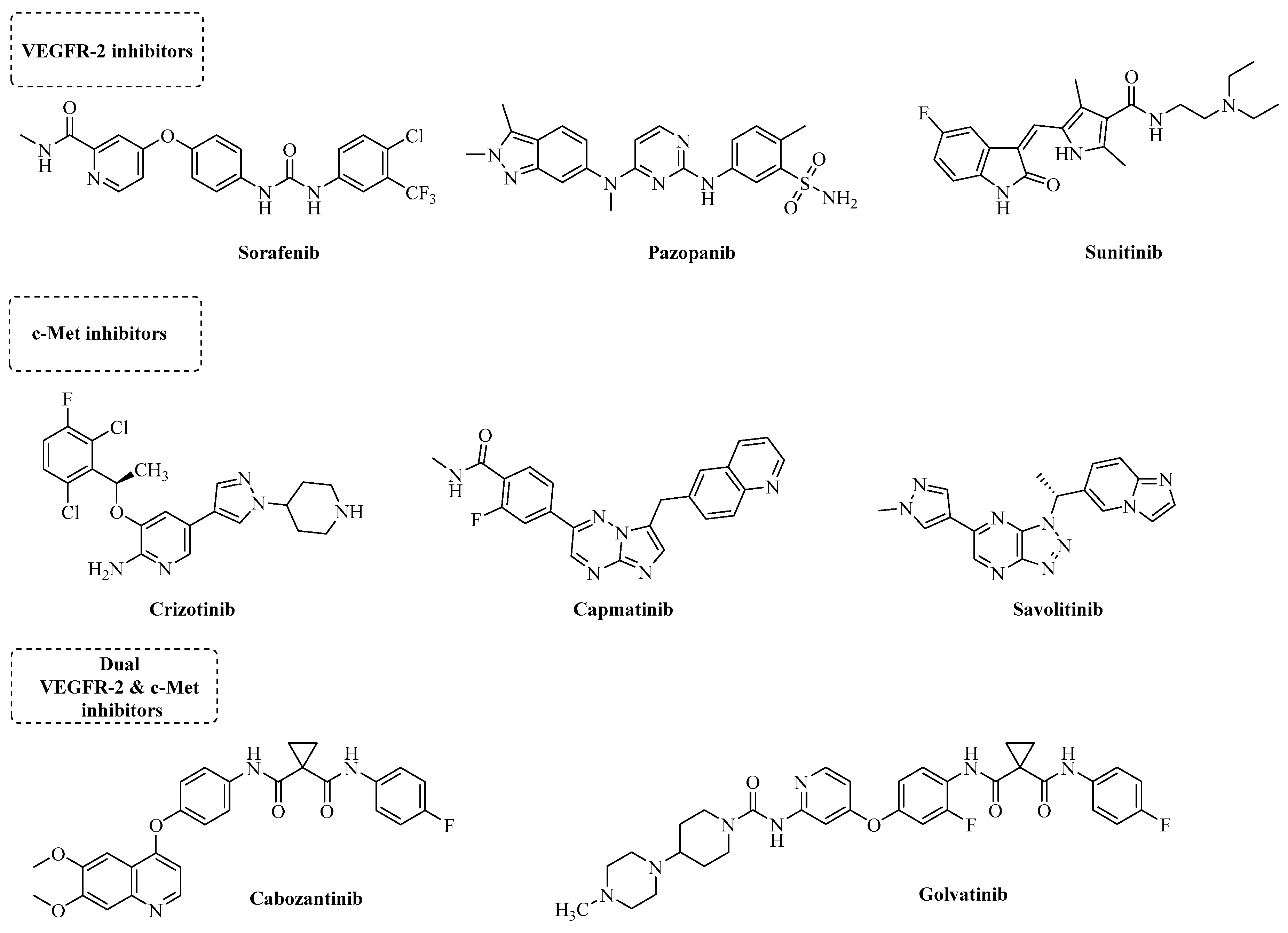

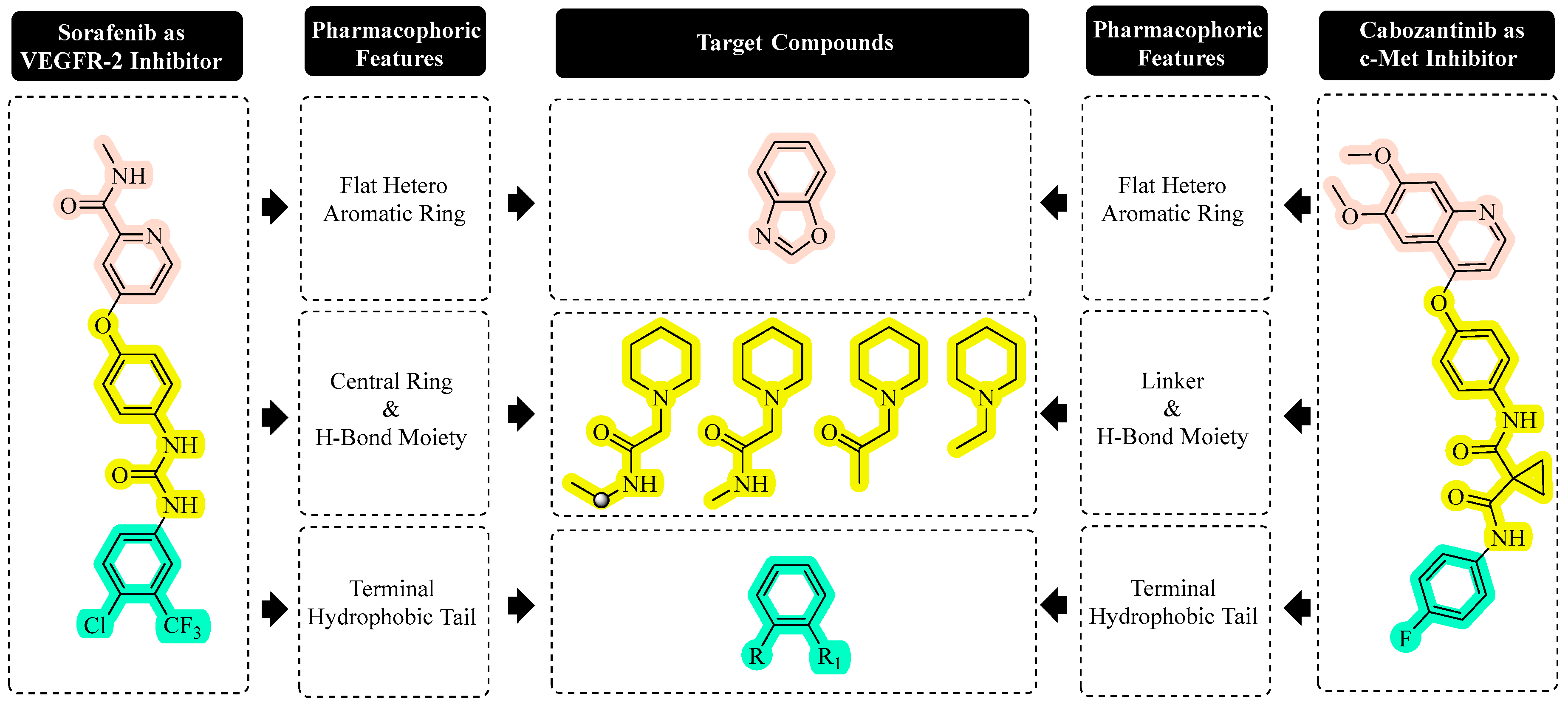

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

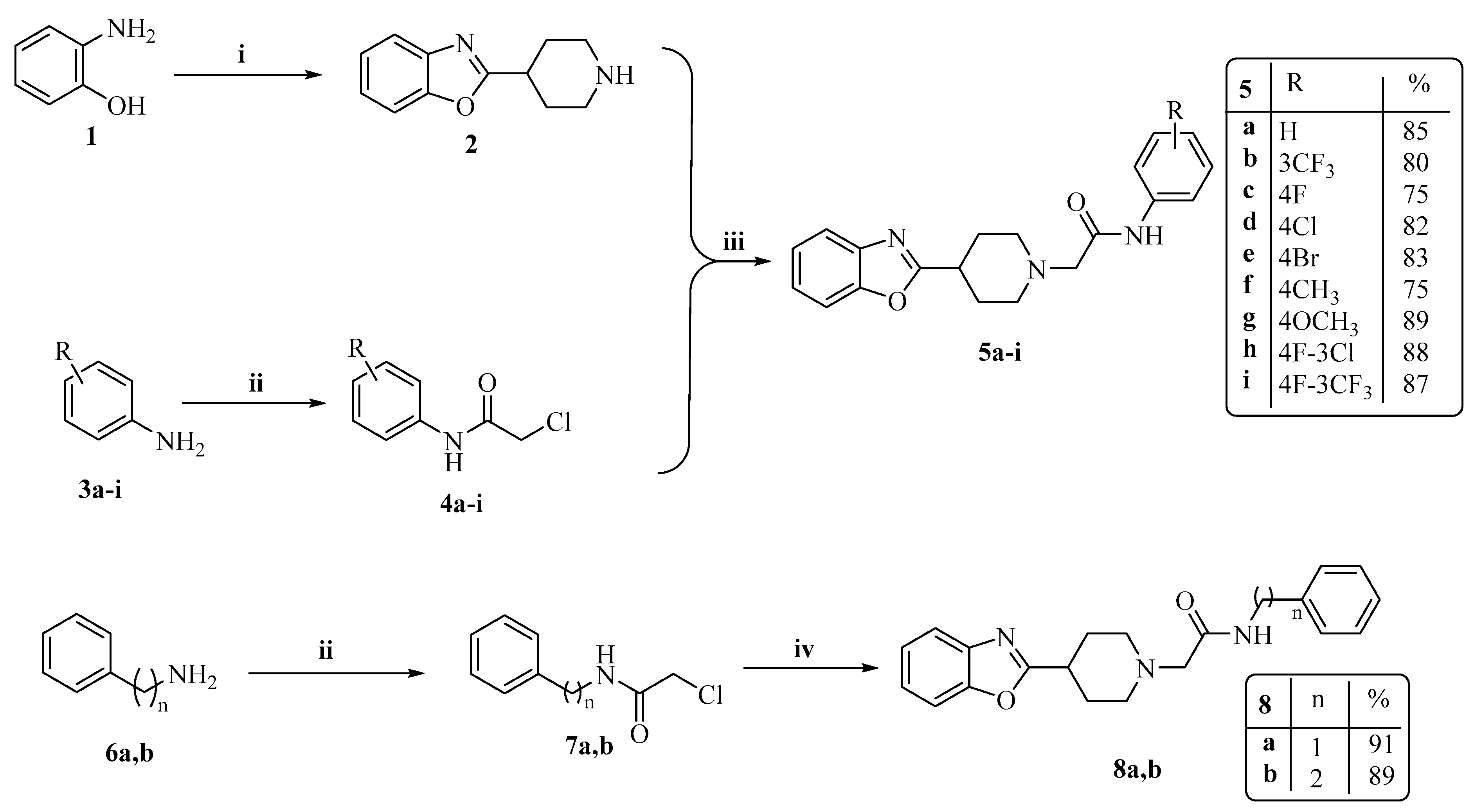

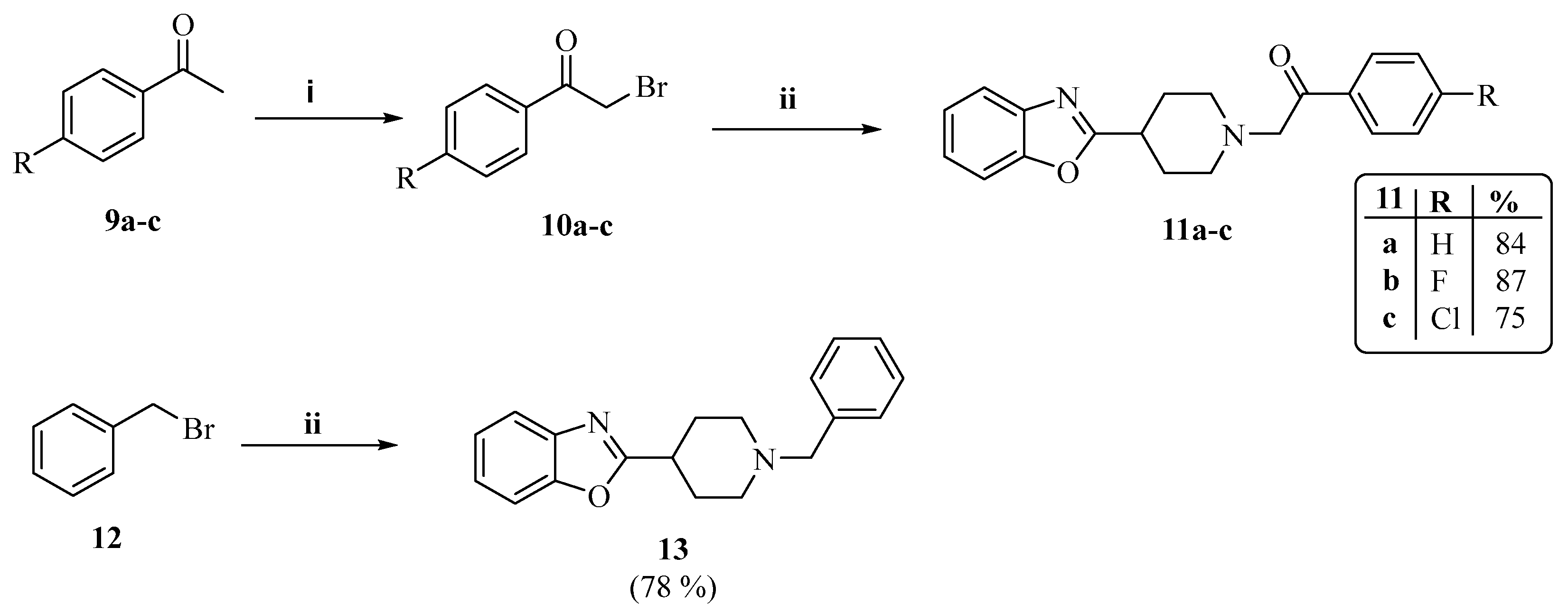

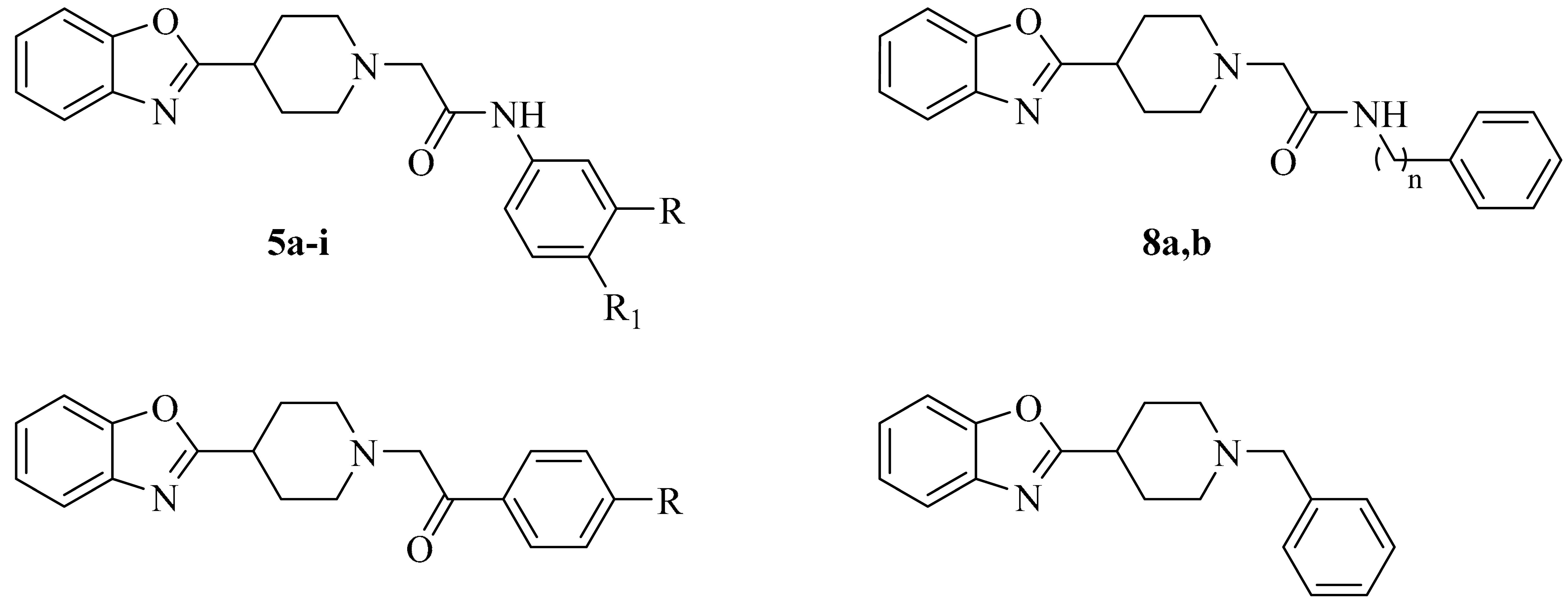

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Biological Activity

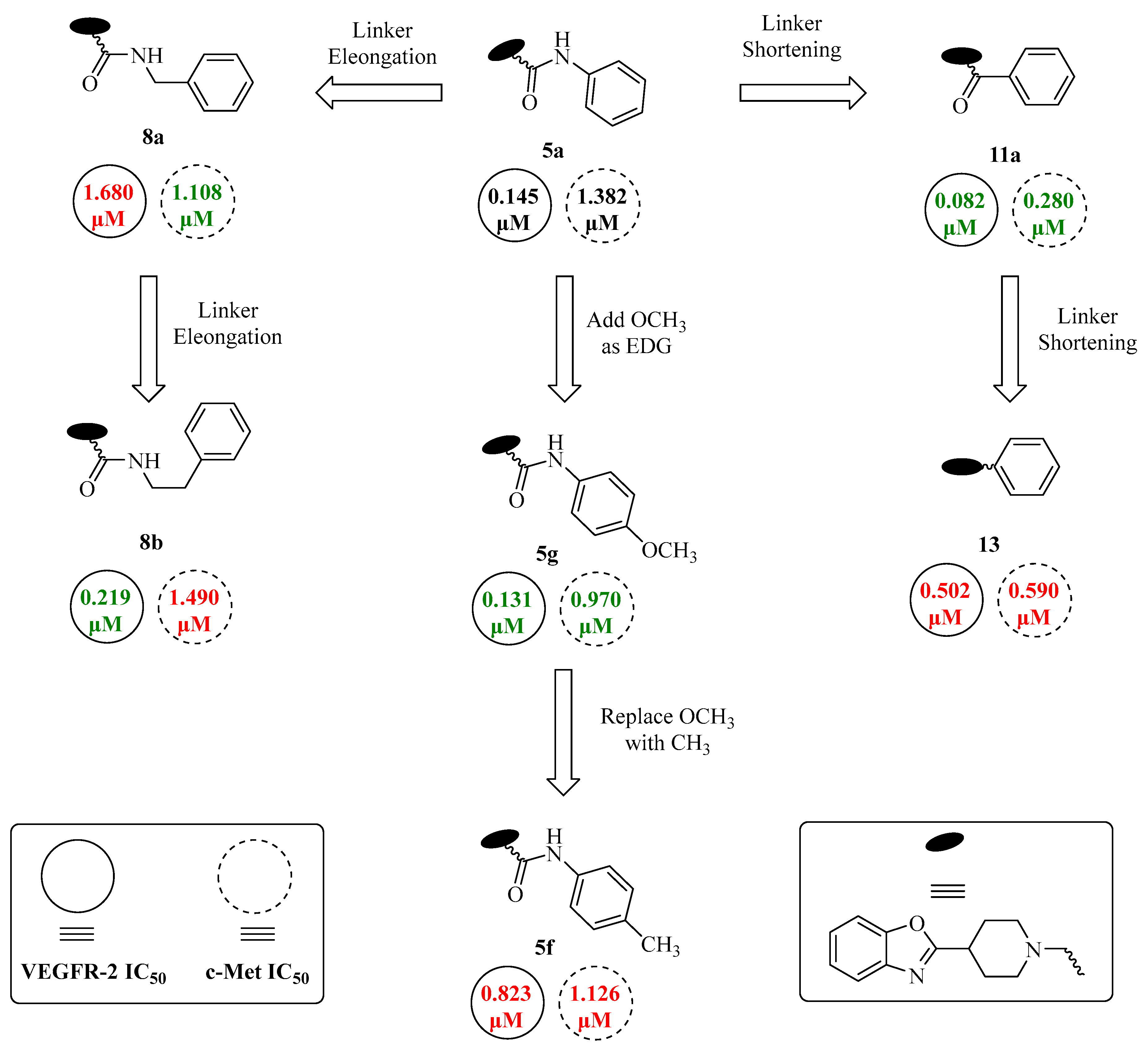

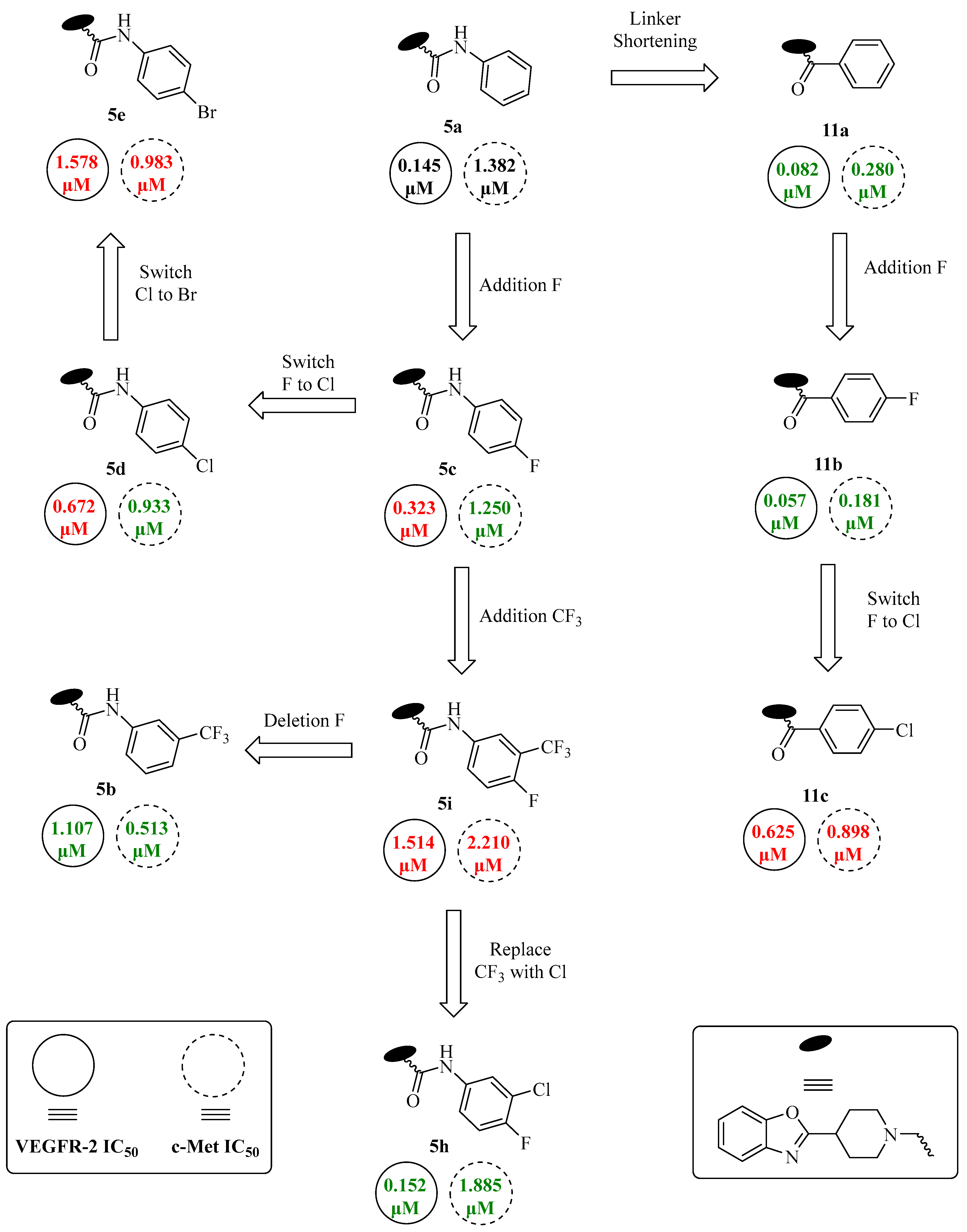

2.2.1. Enzyme Assay

2.2.2. In Vitro Antiproliferative Activity and Selectivity

2.2.3. Cytotoxic Effects In Vitro on MCF-10A (Normal Cells)

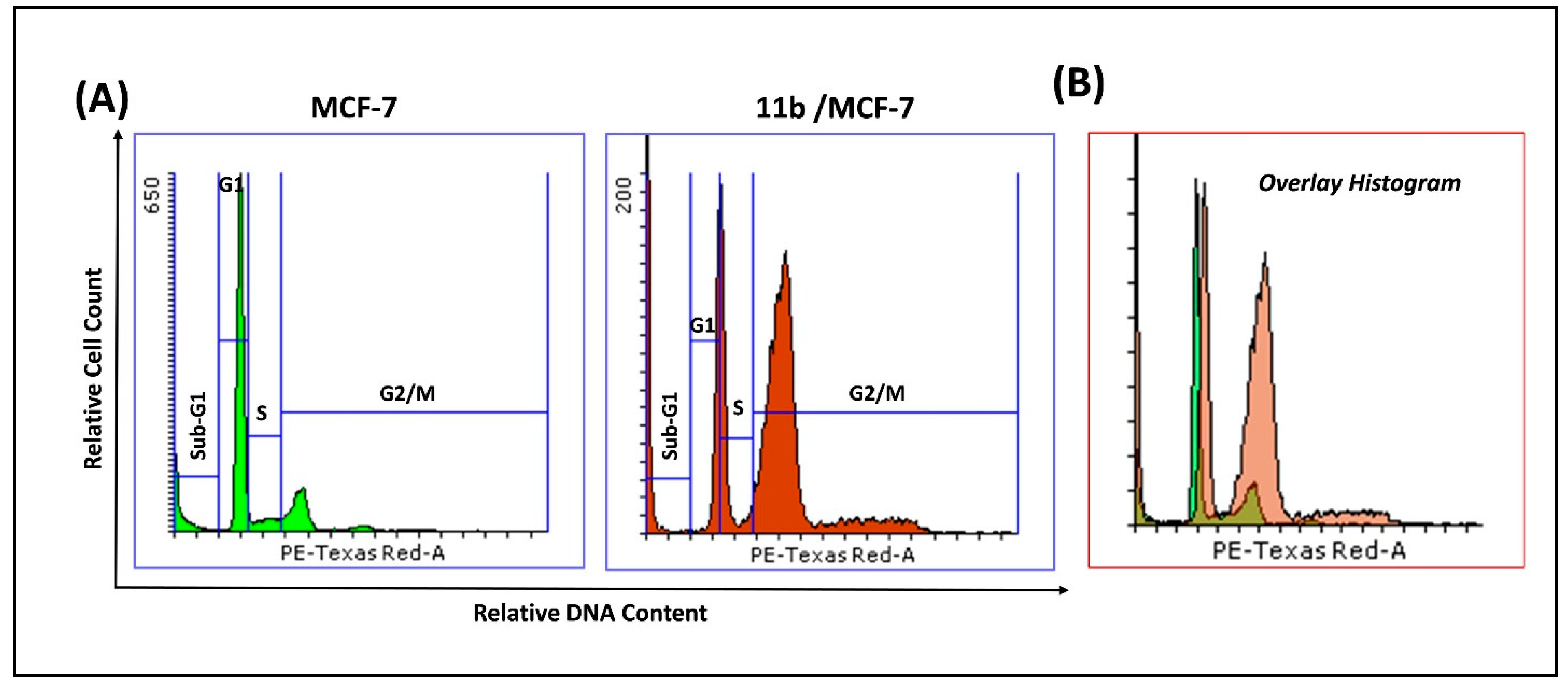

2.2.4. Cell Cycle Analysis in MCF-7 Cells Treated with 11b

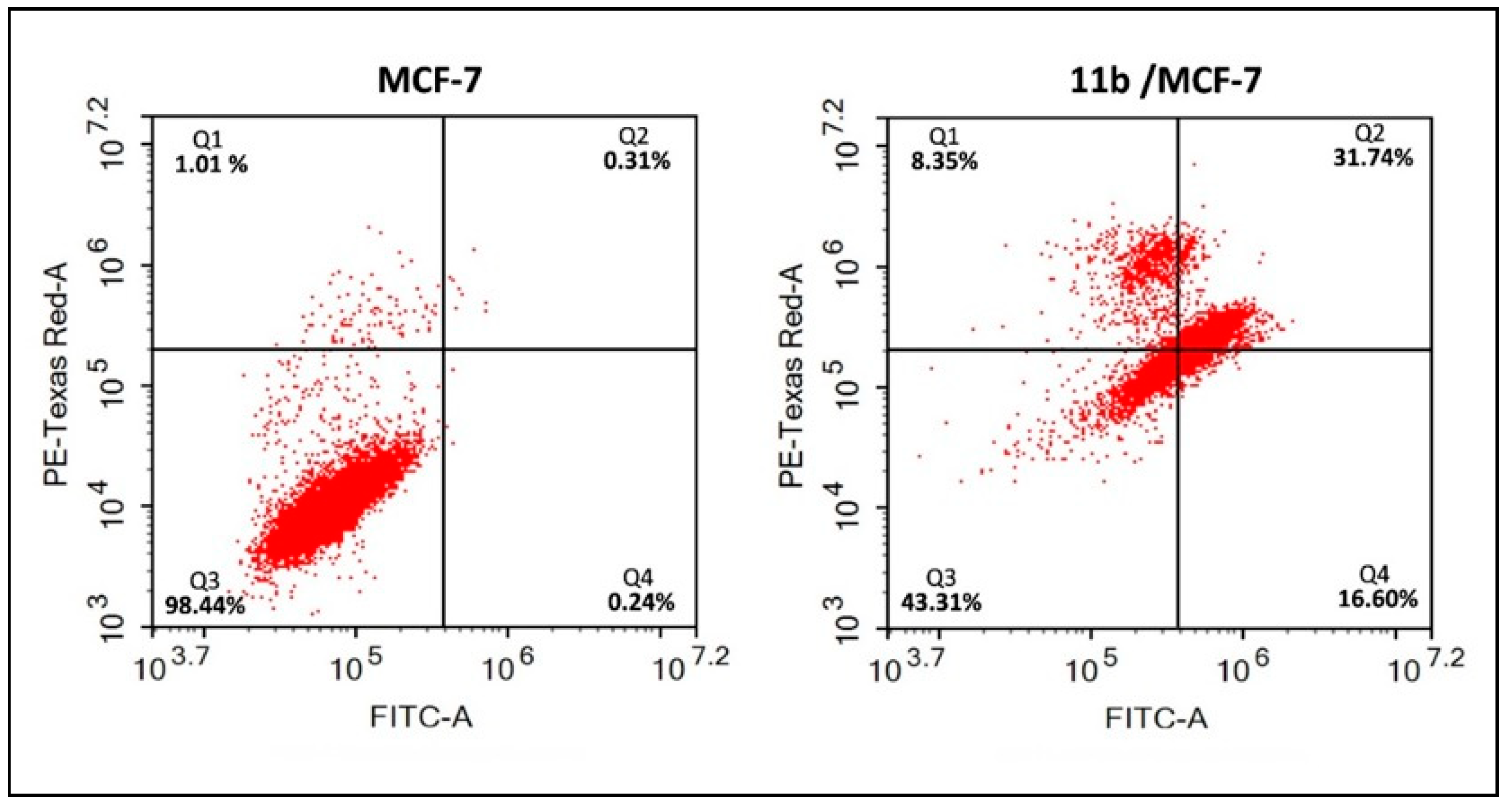

2.2.5. Annexin V-FITC/Propidium Iodide (PI) Assay for Compound 11b in MCF-7 Cells

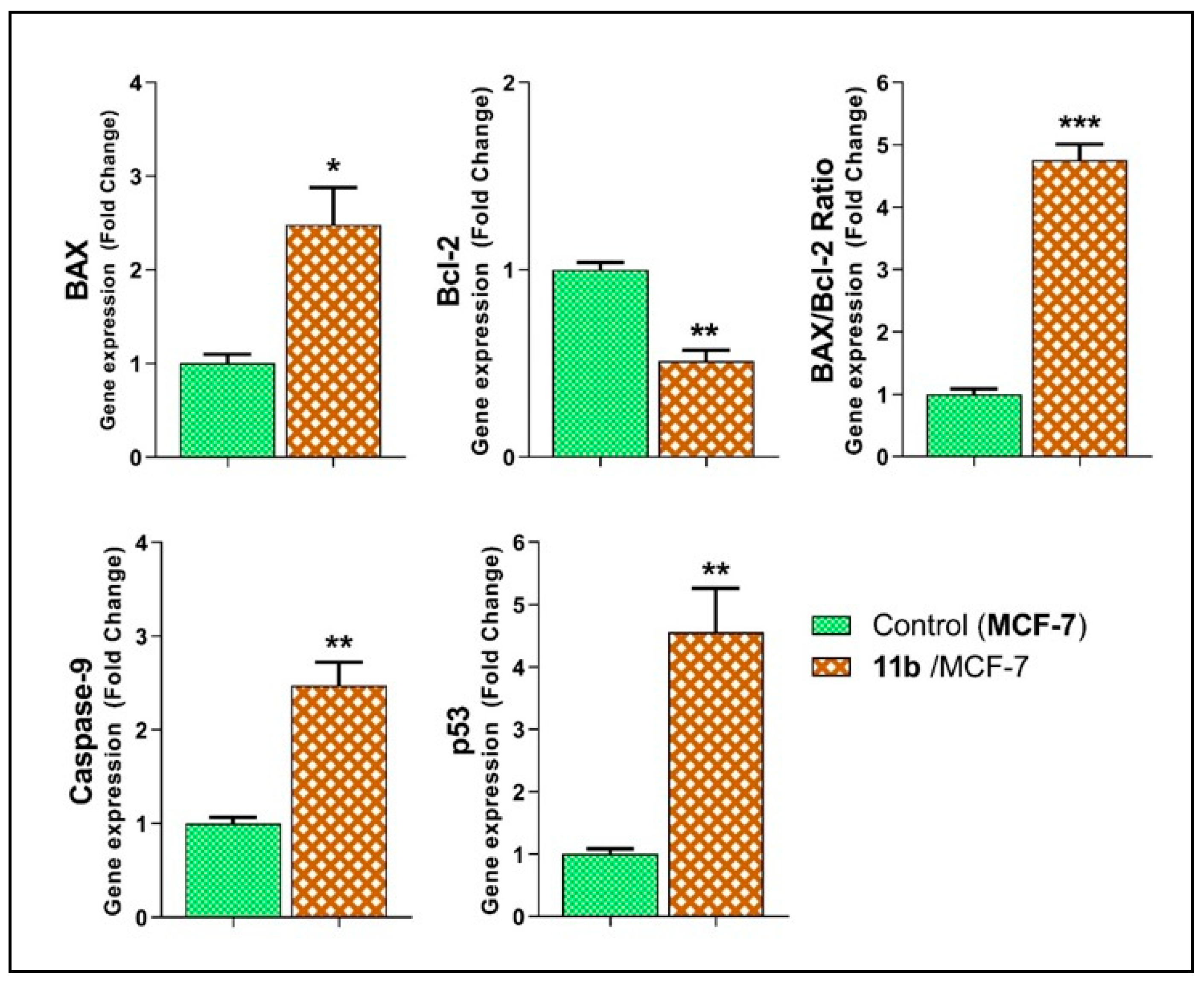

2.2.6. Effects of Compound 11b on the Apoptotic Markers

2.3. Molecular Modeling Study

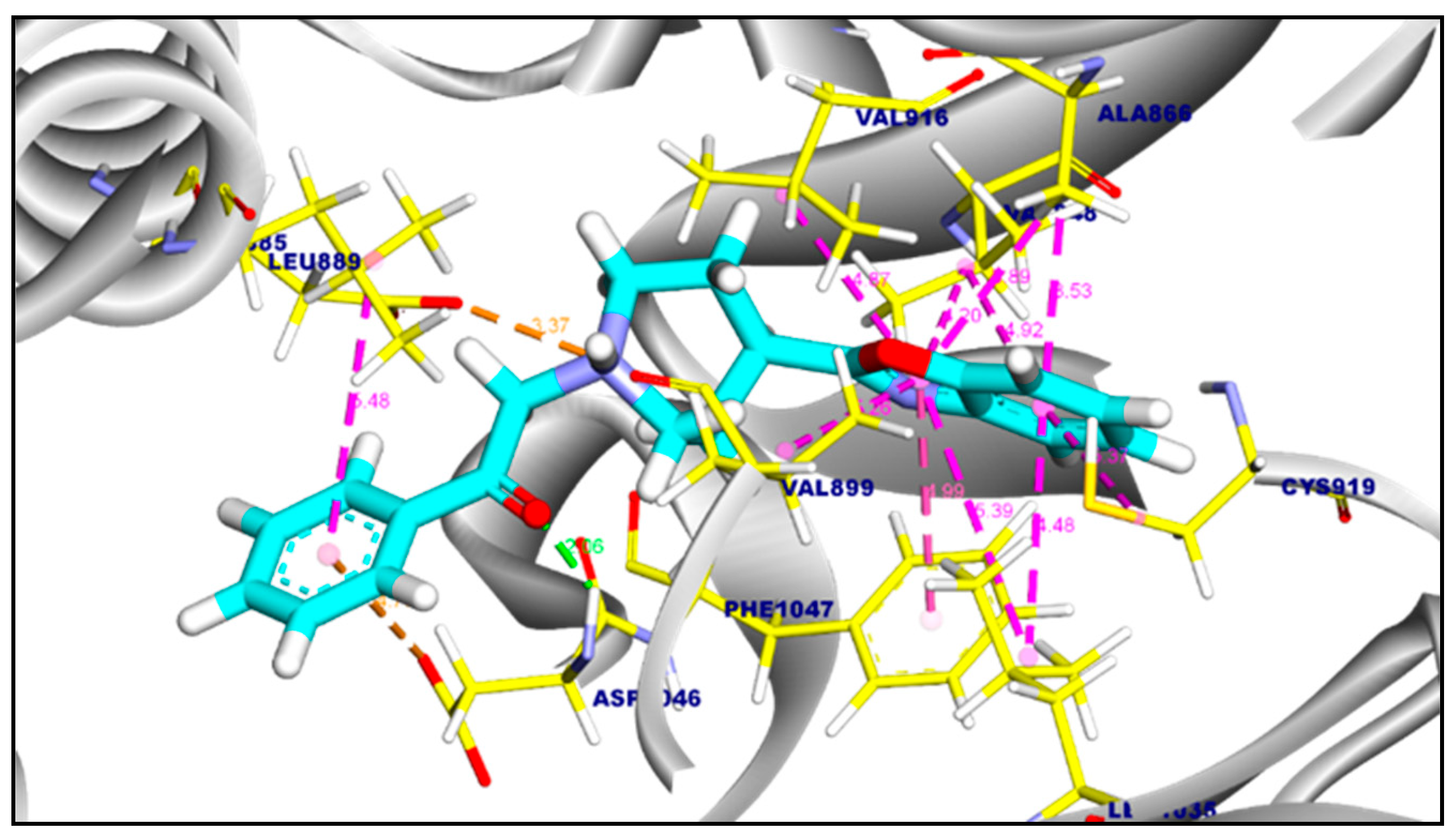

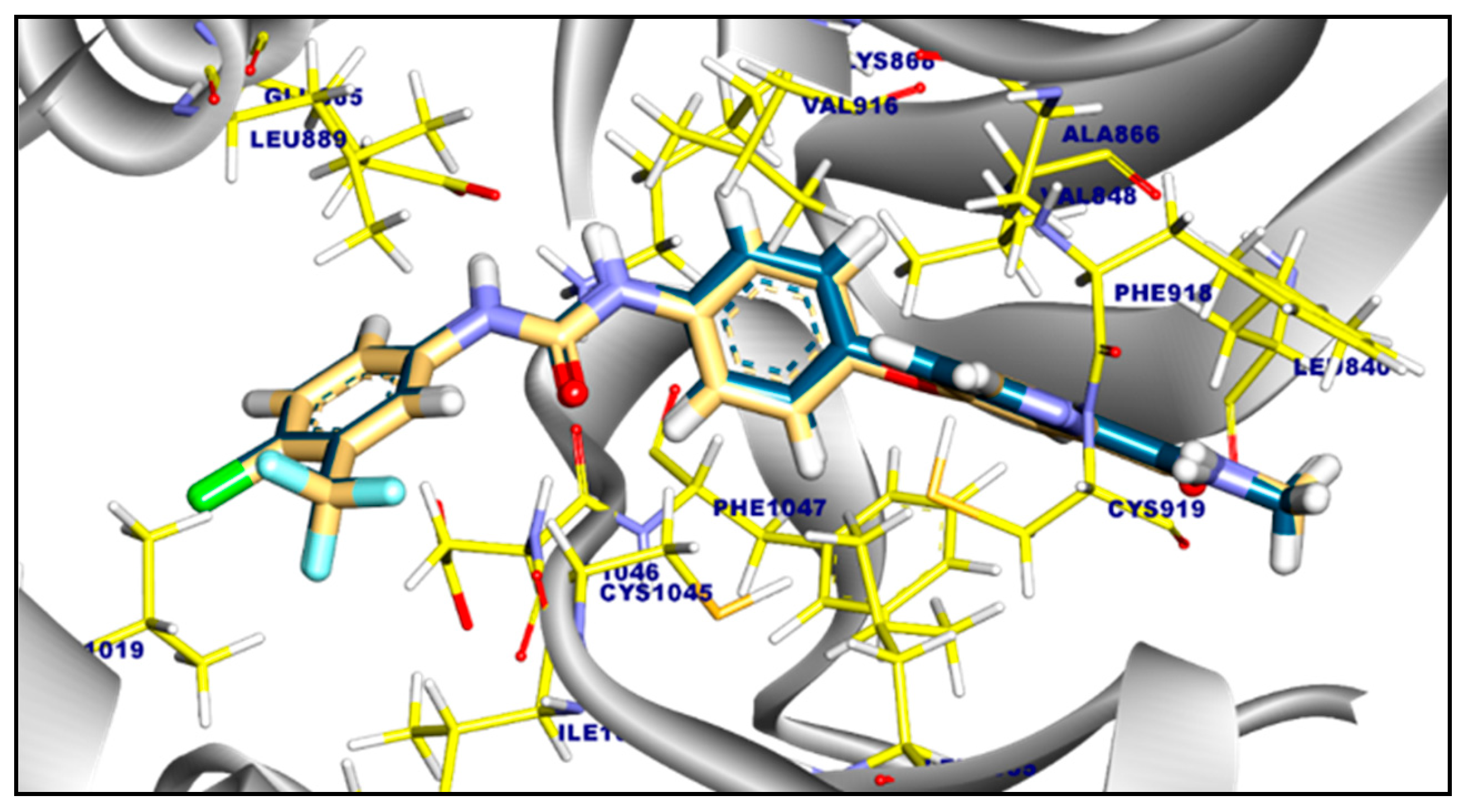

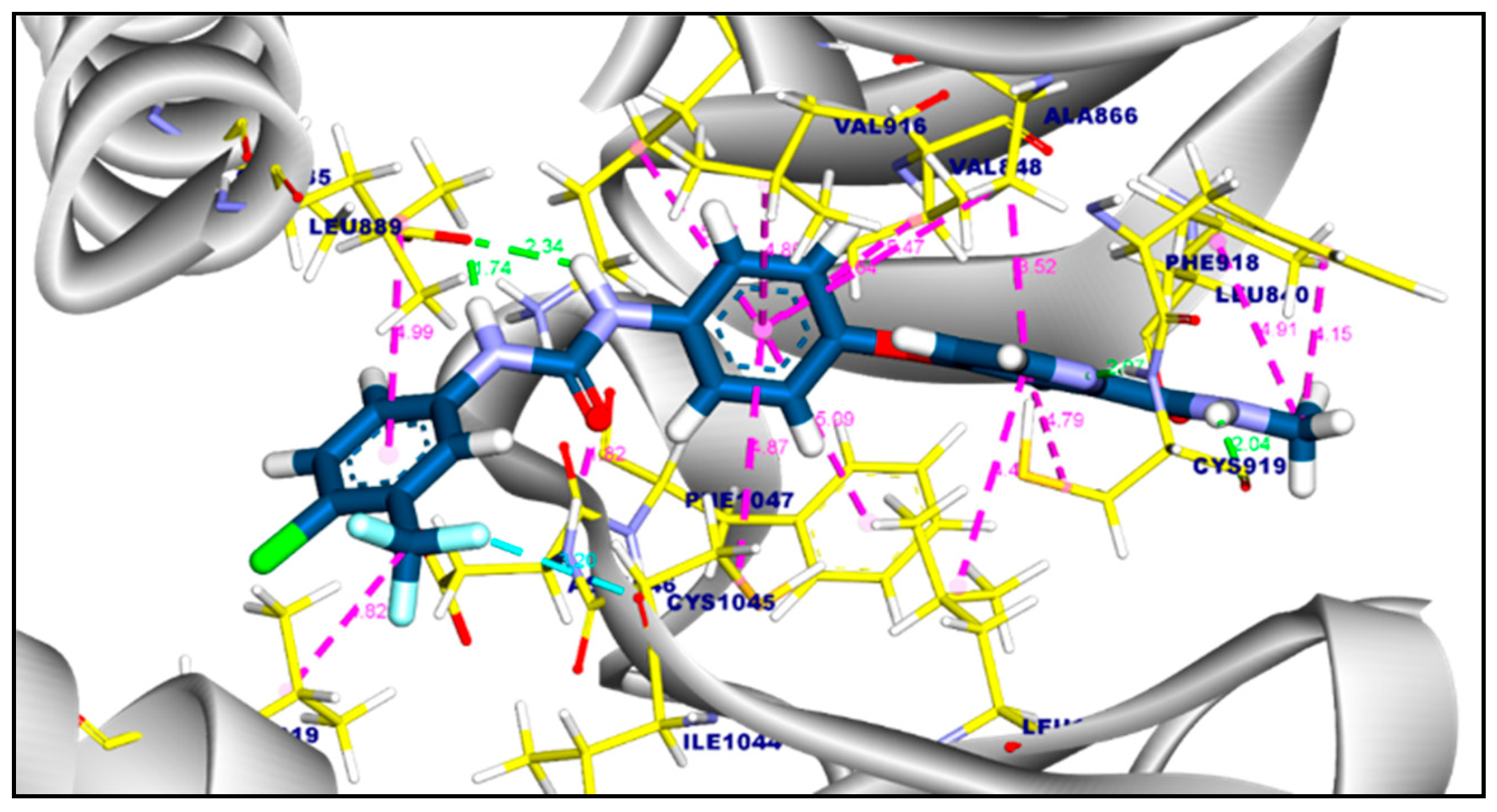

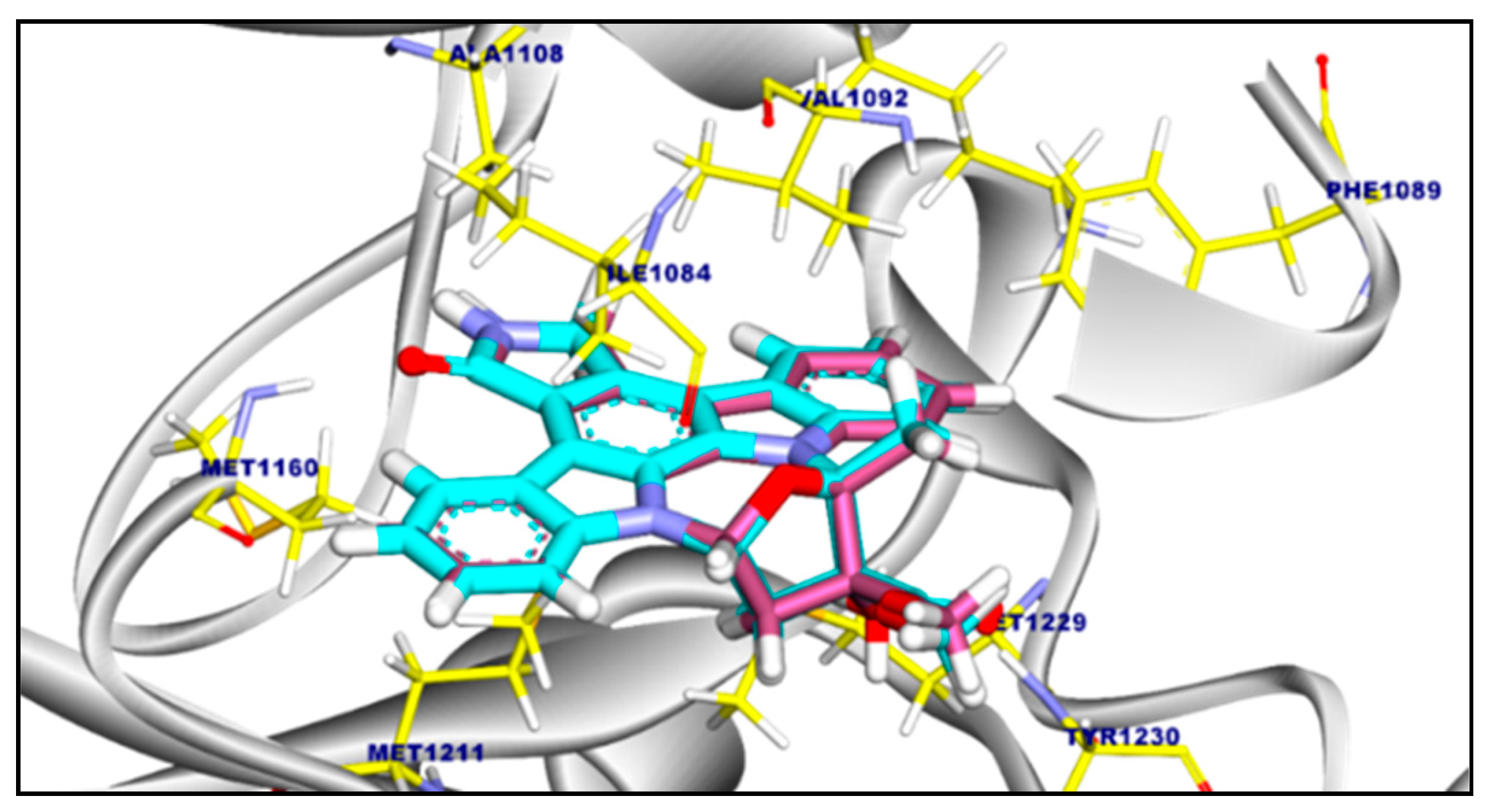

2.3.1. Molecular Docking of Compounds 11a and 11b Against VEGFR-2 TK

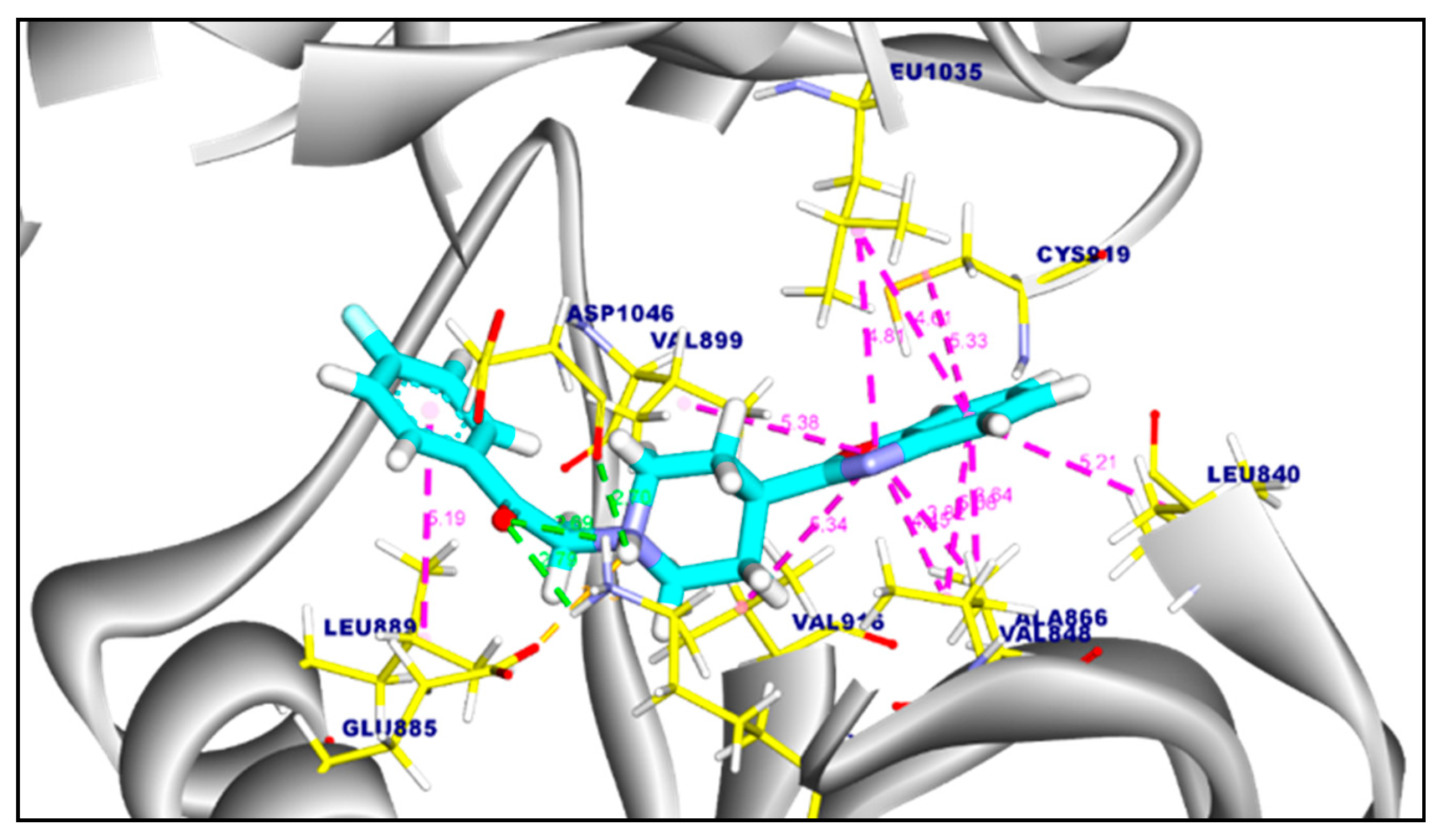

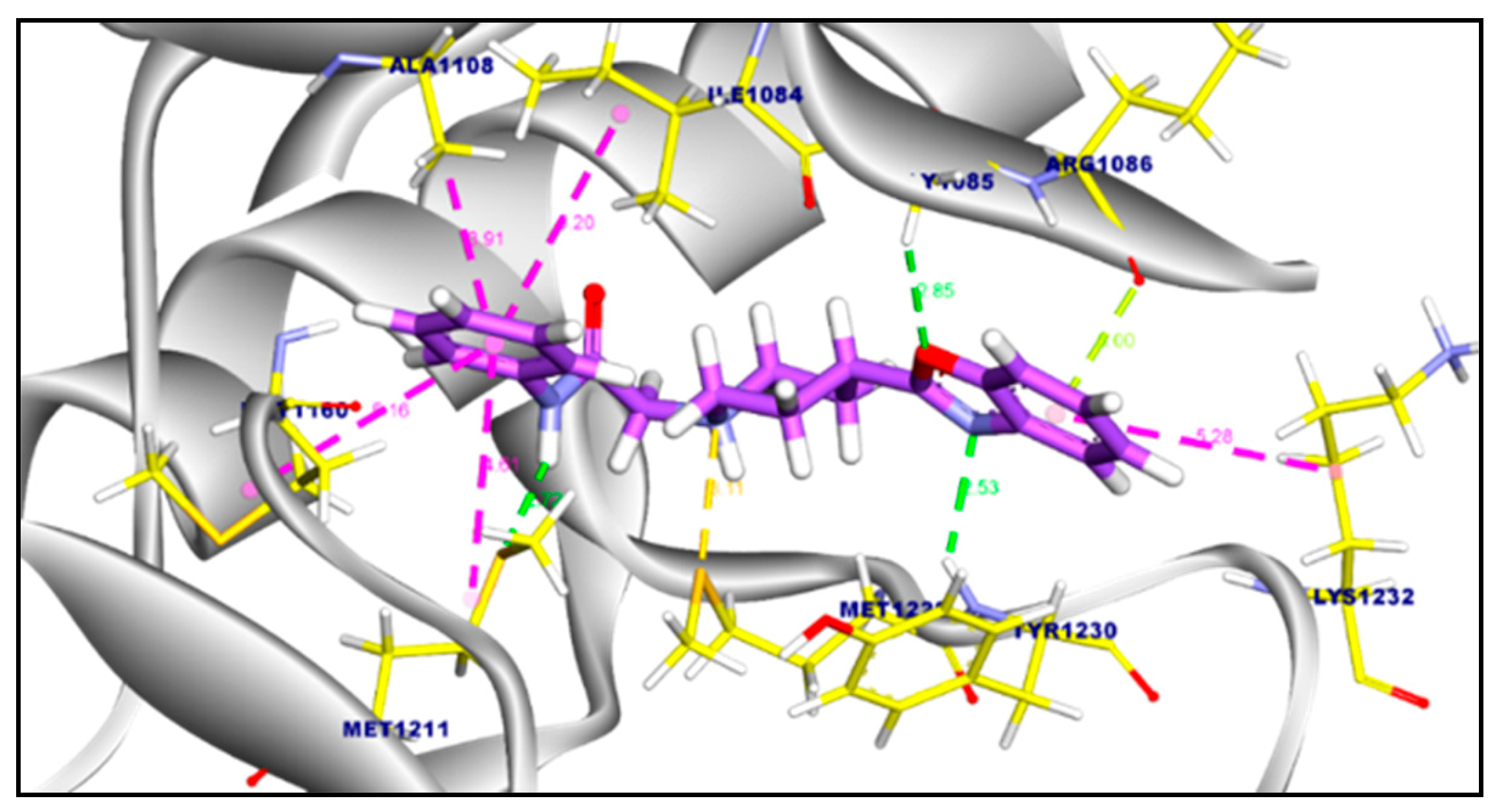

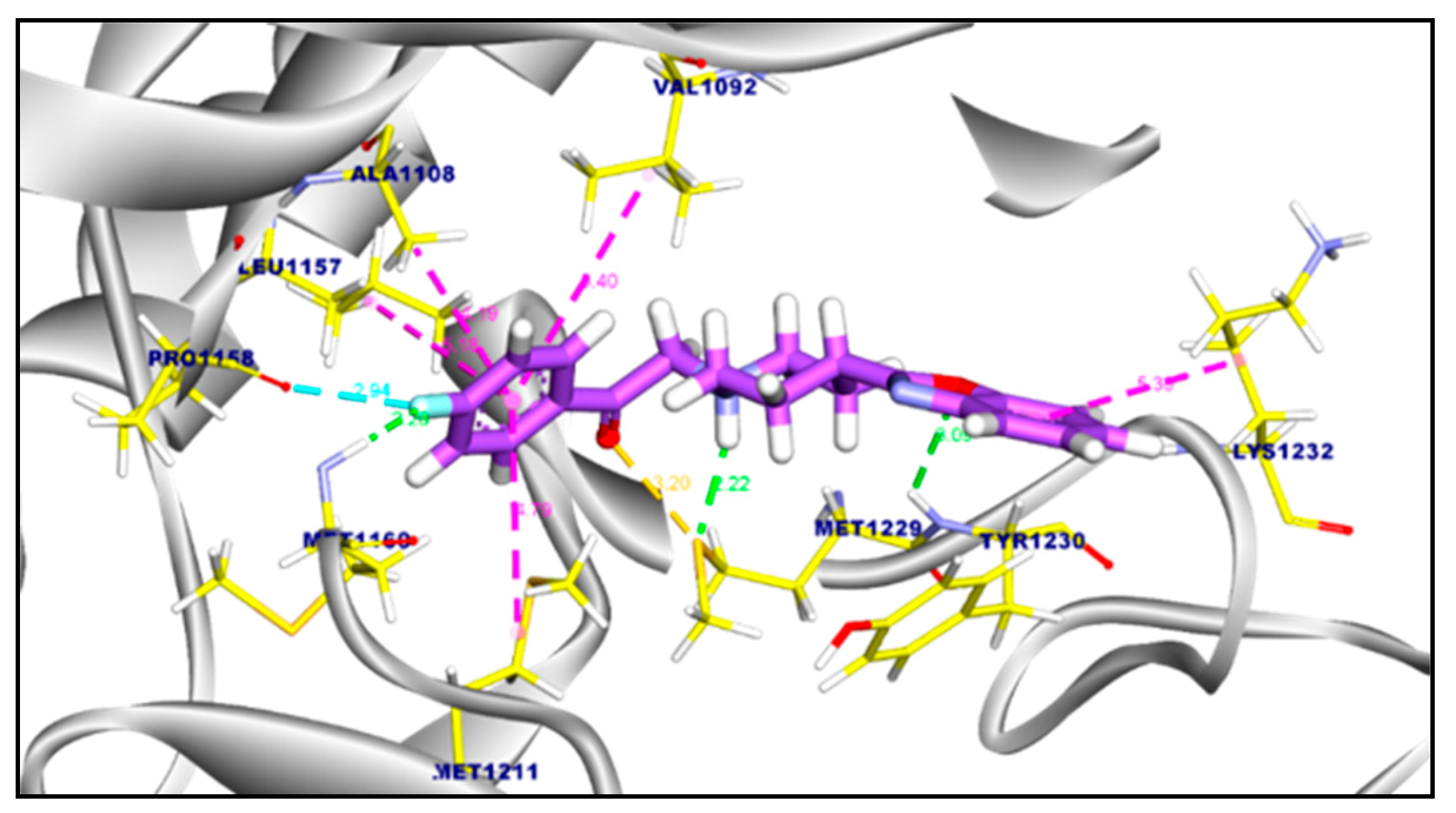

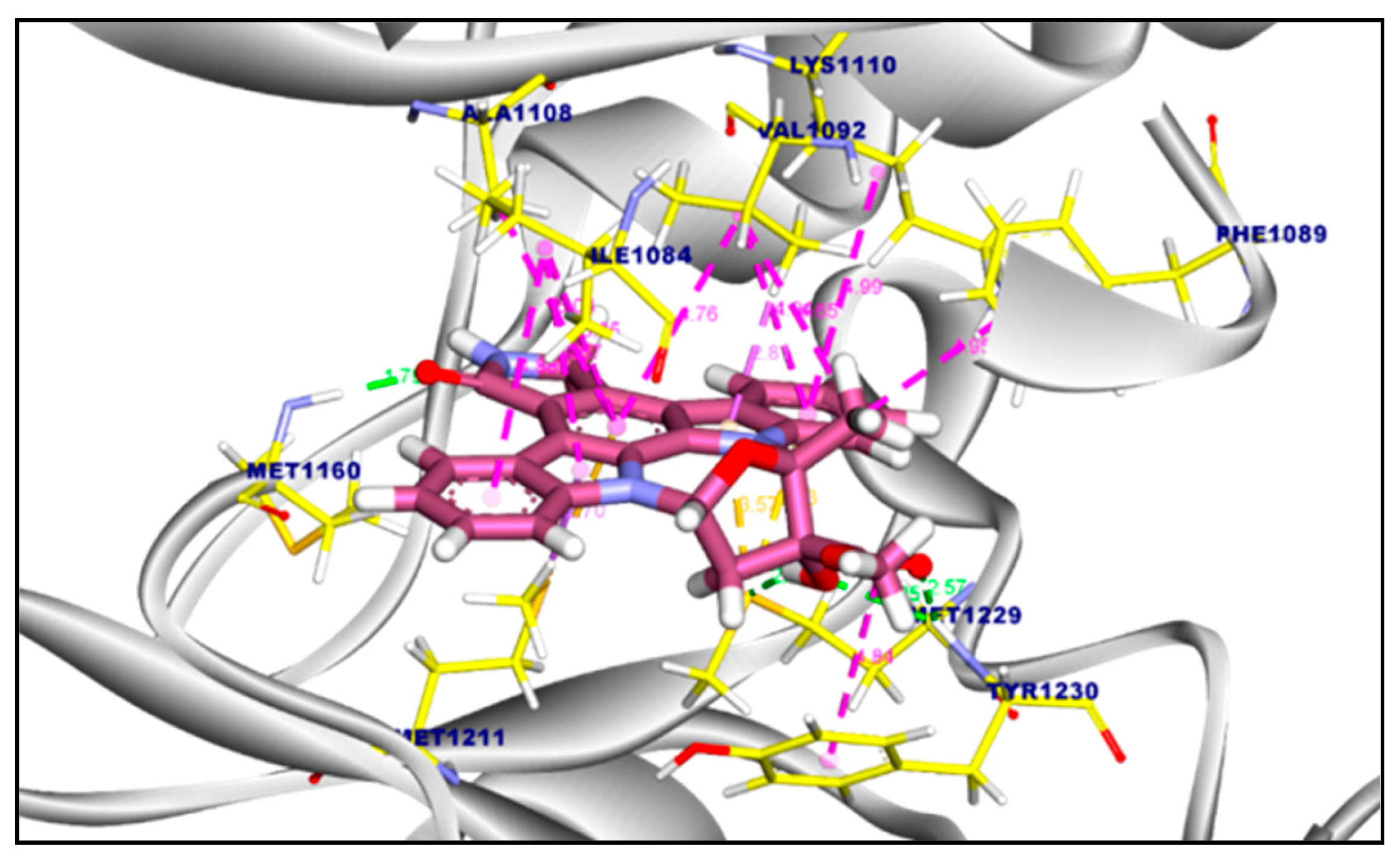

2.3.2. Molecular Docking of Compound 11a and 11b Against c-Met Kinase

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General

3.1.2. The General Synthesis of Target Piperidinyl-Based Benzoxazole Derivatives (5a–i, 8a,b, 11a–c and 13)

3.2. Biology Protocols

3.2.1. VEGFR-2 Inhibition Assay

3.2.2. c-Met Inhibition Assay

3.2.3. In Vitro Antiproliferative Assay

3.2.4. Cell Cycle Analysis

3.2.5. Detection of Apoptosis

3.2.6. Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

3.2.7. Molecular Modelling

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhat, G.R.; Sethi, I.; Sadida, H.Q.; Rah, B.; Mir, R.; Algehainy, N.; Albalawi, I.A.; Masoodi, T.; Subbaraj, G.K.; Jamal, F. Cancer cell plasticity: From cellular, molecular, and genetic mechanisms to tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024, 43, 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellazzo, A.; Montico, B.; Guerrieri, R.; Colizzi, F.; Steffan, A.; Polesel, J.; Fratta, E. Unraveling the role of hypoxia-inducible factors in cutaneous melanoma: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.A.; Kamal, M.A.; Akhtar, S. Tumor angiogenesis and VEGFR-2: Mechanism, pathways and current biological therapeutic interventions. Curr. Drug Metab. 2021, 22, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abhinand, C.S.; Raju, R.; Soumya, S.J.; Arya, P.S.; Sudhakaran, P.R. VEGF-A/VEGFR2 signaling network in endothelial cells relevant to angiogenesis. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 10, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, P.J.; Nemade, A.R.; Shirkhedkar, A.A. Recent updates on potential of VEGFR-2 small-molecule inhibitors as anticancer agents. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33384–33417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacche, R.N.; Assaraf, Y.G. Redundant angiogenic signaling and tumor drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updates 2018, 36, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhong, M.; Zhong, H.; Ruan, R.; Xiong, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Deng, J. Targeting HGF/c-MET signaling to regulate the tumor microenvironment: Implications for counteracting tumor immune evasion. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawale, S.A.; Deokar, A.V.; Firdous, M.A.; Pandit, M.; Chaudhari, M.Y.; Salve, S.B.; Khandgaonkar, M.; Parwe, M.; Khalse, R.; Dake, S.G. Exploring the potential of small molecules of dual c-Met and VEGFR inhibitors for advances and future drug discovery in cancer therapy. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. MET-targeted therapies and clinical outcomes: A systematic literature review. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2022, 26, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; He, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Ouyang, L. Recent advances in the development of dual VEGFR and c-Met small molecule inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 108, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, E.S.; Barone, A.K.; Chatterjee, S.; Mishra-Kalyani, P.S.; Shen, Y.-L.; Isikwei, E.; Zhao, H.; Bi, Y.; Liu, J.; Rahman, N.A. FDA approval summary: Cabozantinib for differentiated thyroid cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4173–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Jeong, K.-W.; Lee, Y.; Song, J.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, G.S.; Kim, Y. Pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening studies for new VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 5420–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouattour, M.; Raymond, E.; Qin, S.; Cheng, A.L.; Stammberger, U.; Locatelli, G.; Faivre, S. Recent developments of c-Met as a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018, 67, 1132–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Yamada, M.; Yoshida, S.; Soneda, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Nizato, T.; Suzuki, K.; Konno, F. Benzoxazole Derivatives as Novel 5-HT3 Receptor Partial Agonists in the Gut. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 3015–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefny, S.M.; El-Moselhy, T.F.; El-Din, N.; Ammara, A.; Angeli, A.; Ferraroni, M.; El-Dessouki, A.M.; Shaldam, M.A.; Yahya, G.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; et al. A new framework for novel analogues of pazopanib as potent and selective human carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: Design, repurposing rational, synthesis, crystallographic, in vivo and in vitro biological assessments. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 274, 116527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, H.O.; Saleh, M.M.; Ammara, A.; Khaleel, E.F.; Badi, R.; Khater, Y.T.T.; Rasheed, R.A.; Attia, A.A.; Hefny, S.M.; Elkaeed, E.B.; et al. Discovery of Novel Pyridazine-Tethered Sulfonamides as Carbonic Anhydrase II Inhibitors for the Management of Glaucoma. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 1611–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Otero, P.; Pereira, A.G.; Chamorro, F.; Carpena, M.; Echave, J.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Status and challenges of plant-anticancer compounds in cancer treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Cell cycle regulation and anticancer drug discovery. Cancer Biol. Med. 2017, 14, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z. Regulation of cell cycle progression by growth factor-induced cell signaling. Cells 2021, 10, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skladanowski, A.; Bozko, P.; Sabisz, M. DNA structure and integrity checkpoints during the cell cycle and their role in drug targeting and sensitivity of tumor cells to anticancer treatment. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2951–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhivotovsky, B.; Orrenius, S. Cell cycle and cell death in disease: Past, present and future. J. Intern. Med. 2010, 268, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, R. Understanding apoptosis and apoptotic pathways targeted cancer therapeutics. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefranc, F.; Facchini, V.; Kiss, R. Proautophagic drugs: A novel means to combat apoptosis-resistant cancers, with a special emphasis on glioblastomas. Oncologist 2007, 12, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.d.S.; Bressan, F.F.; Zecchin, K.G.; Vercesi, A.E.; Mesquita, L.G.; Merighe, G.K.F.; King, W.A.; Ohashi, O.M.; Pimentel, J.R.V.; Perecin, F. Serum-starved apoptotic fibroblasts reduce blastocyst production but enable development to term after SCNT in cattle. Cloning Stem Cells 2009, 11, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Mousa, M.H.A.; Sharaky, M.; Mourad, M.A.E.; El-Dessouki, A.M.; Hamouda, A.O.; Alnajjar, R.; Ayed, A.A.; Shaldam, M.A.; Tawfik, H.O. Lead Optimization of BIBR1591 To Improve Its Telomerase Inhibitory Activity: Design and Synthesis of Novel Four Chemical Series with In Silico, In Vitro, and In Vivo Preclinical Assessments. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 492–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Marriner, G.A.; Wang, X.; Bowman, P.D.; Kerwin, S.M.; Stavchansky, S. Synthesis of a series of caffeic acid phenethyl amide (CAPA) fluorinated derivatives: Comparison of cytoprotective effects to caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 5032–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Mohamed, A.F.; Shalaby, H.N.; Elmaaty, A.A.; El-Shiekh, R.A.; Zeidan, M.A.; Alnajjar, R.; Alzahrani, A.Y.A.; Al Mughram, M.H.; Shaldam, M.A.; et al. Donepezil-based rational design of N-substituted quinazolinthioacetamide candidates as potential acetylcholine esterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: In vitro and in vivo studies. RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 2078–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefny, S.M.; El-Moselhy, T.F.; El-Din, N.; Giovannuzzi, S.; Bin Traiki, T.; Vaali-Mohammed, M.-A.; El-Dessouki, A.M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Sugiura, M.; Shaldam, M.A. Discovery and mechanistic studies of dual-target hits for carbonic anhydrase IX and VEGFR-2 as potential agents for solid tumors: X-ray, in vitro, in vivo, and in silico investigations of coumarin-based thiazoles. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 7406–7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Held, P.; Buehrer, L. The Synergy™ HT: A unique multi-detection microplate reader for HTS and drug discovery. J. Assoc. Lab. Autom. 2003, 8, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gediya, P.; Tulsian, K.; Vyas, V.K.; Dhameliya, T.M.; Parikh, P.K.; Ghate, M.D. Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel thiazole derivatives as c-Met kinase inhibitors and anticancer agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1317, 139074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, N.A.; Abu, N.; Ho, W.Y.; Zamberi, N.R.; Tan, S.W.; Alitheen, N.B.; Long, K.; Yeap, S.K. Cytotoxicity of eupatorin in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells via cell cycle arrest, anti-angiogenesis and induction of apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, B. Griffipavixanthone induces apoptosis of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells in vitro. Breast Cancer 2019, 26, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, D.; Schadt, O.; Stieber, F.; Meyring, M.; Grädler, U.; Bladt, F.; Friese-Hamim, M.; Knühl, C.; Pehl, U.; Blaukat, A. Identification and optimization of pyridazinones as potent and selective c-Met kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 1597–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTigue, M.; Murray, B.W.; Chen, J.H.; Deng, Y.-L.; Solowiej, J.; Kania, R.S. Molecular conformations, interactions, and properties associated with drug efficiency and clinical performance among VEGFR TK inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18281–18289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | R | R1 | n ** | IC50 (μM) (Mean ± SEM) | |

| VEGFR-2 | c-Met | ||||

| 5a | H | H | - | 0.145 ± 0.04 | 1.382 ± 0.51 |

| 5b | CF3 | H | - | 1.107 ± 0.39 | 0.513 ± 0.12 |

| 5c | H | F | - | 0.323 ± 0.10 | 1.250 ± 0.29 |

| 5d | H | Cl | - | 0.672 ± 0.29 | 0.933 ± 0.08 |

| 5e | H | Br | - | 1.578 ± 0.53 | 0.983 ± 0.47 |

| 5f | H | CH3 | - | 0.823 ± 0.10 | 1.126 ± 0.38 |

| 5g | H | OCH3 | - | 0.131 ± 0.03 | 0.970 ± 0.09 |

| 5h | Cl | F | - | 0.152 ± 0.03 | 1.885 ± 0.30 |

| 5i | CF3 | F | - | 1.514 ± 0.45 | 2.210 ± 0.37 |

| 8a | - | - | 1 | 1.680 ± 0.42 | 1.108 ± 0.51 |

| 8b | - | - | 2 | 0.219 ± 0.02 | 1.490 ± 0.20 |

| 11a | H | - | - | 0.082 ± 0.01 | 0.280 ± 0.03 |

| 11b | F | - | - | 0.057 ± 0.01 | 0.181 ± 0.04 |

| 11c | Cl | - | - | 0.625 ± 0.24 | 0.898 ± 0.16 |

| 13 | - | - | - | 0.502 ± 0.11 | 0.590 ± 0.21 |

| Sorafenib | - | - | - | 0.058 ± 0.01 | -- |

| Staurosporine | - | - | - | -- | 0.237 ± 0.01 |

| Code | In Vitro Cytotoxicity [IC50, µM ± SEM] a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 | A549 | PC-3 | MCF-10A | MCF-10A/MCF-7 Ratio | |

| 5a | 16.29 ± 2.07 | 23.60 ± 1.01 | 16.14 ± 1.13 | 28.31 ± 1.23 | 1.74 |

| 5g | 17.23 ± 1.29 | 9.32 ± 1.26 | 22.63 ± 1.50 | 30.35 ± 2.38 | 1.76 |

| 5h | 14.01 ± 0.94 | 14.86 ± 0.82 | 24.89 ± 3.01 | 27.85 ± 3.29 | 1.99 |

| 11a | 6.25 ± 0.63 | 8.33 ± 0.64 | 15.95 ± 0.58 | 27.17 ± 2.10 | 4.35 |

| 11b | 4.30 ± 0.25 | 6.68 ± 1.08 | 7.06 ± 1.10 | 34.25 ± 1.24 | 7.97 |

| Sorafenib | 4.95 ± 0.92 | 6.32 ± 0.66 | 6.57 ± 0.61 | 21.63 ± 2.81 | 4.37 |

| Sample | Gene Expression (Normalized to GAPDH) a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAX | Bcl-2 | BAX/Bcl-2 Ratio | Caspase-9 | p53 | |

| MCF-7 cells | 1.00 ± 0.09 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 1.00 ± 0.08 |

| 11b/MCF-7 | 2.48 ± 0.40 * | 0.51 ± 0.06 ** | 4.76 ± 0.26 *** | 2.48 ± 0.24 ** | 4.56 ± 0.71 ** |

| Kinase | Kinase Activity (%) | Kinase | Kinase Activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDGFRβ | 65 | BTK | 84 |

| RET | 99 | FLT-3 | 91 |

| GSK3b | 100 | Aurora B | 96 |

| Tested Targets | Compounds | RMSD Value (Å) | Docking (Affinity) Score (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGFR-2 TK | Compound 11a | 0.94 | −8.57 |

| Compound 11b | 1.14 | −8.62 | |

| Sorafenib | 0.15 | −9.18 | |

| c-Met Kinase | Compound 11a | 1.36 | −7.98 |

| Compound 11b | 1.27 | −7.93 | |

| Staurosporine | 0.18 | −9.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eldehna, W.M.; Elsayed, Z.M.; Elnagar, M.R.; El-Said, A.H.; Majrashi, T.A.; Negmeldin, A.T.; Saleh, A.M.; Elrayess, R.; Elnahriry, K.A.; Chen, Z.-L.; et al. Discovery of Novel Piperidinyl-Based Benzoxazole Derivatives as Anticancer Agents Targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met Kinases. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121875

Eldehna WM, Elsayed ZM, Elnagar MR, El-Said AH, Majrashi TA, Negmeldin AT, Saleh AM, Elrayess R, Elnahriry KA, Chen Z-L, et al. Discovery of Novel Piperidinyl-Based Benzoxazole Derivatives as Anticancer Agents Targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met Kinases. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121875

Chicago/Turabian StyleEldehna, Wagdy M., Zainab M. Elsayed, Mohamed R. Elnagar, Ahmed H. El-Said, Taghreed A. Majrashi, Ahmed T. Negmeldin, Abdulrahman M. Saleh, Ranza Elrayess, Khaled A. Elnahriry, Zhi-Long Chen, and et al. 2025. "Discovery of Novel Piperidinyl-Based Benzoxazole Derivatives as Anticancer Agents Targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met Kinases" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121875

APA StyleEldehna, W. M., Elsayed, Z. M., Elnagar, M. R., El-Said, A. H., Majrashi, T. A., Negmeldin, A. T., Saleh, A. M., Elrayess, R., Elnahriry, K. A., Chen, Z.-L., Elagawany, M., & Tawfik, H. O. (2025). Discovery of Novel Piperidinyl-Based Benzoxazole Derivatives as Anticancer Agents Targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met Kinases. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121875