Review of the Most Important Research Trends in Potential Chemotherapeutics Based on Coordination Compounds of Ruthenium, Rhodium and Iridium

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Potential Ruthenium-Based Chemotherapeutics: Key Research Trends

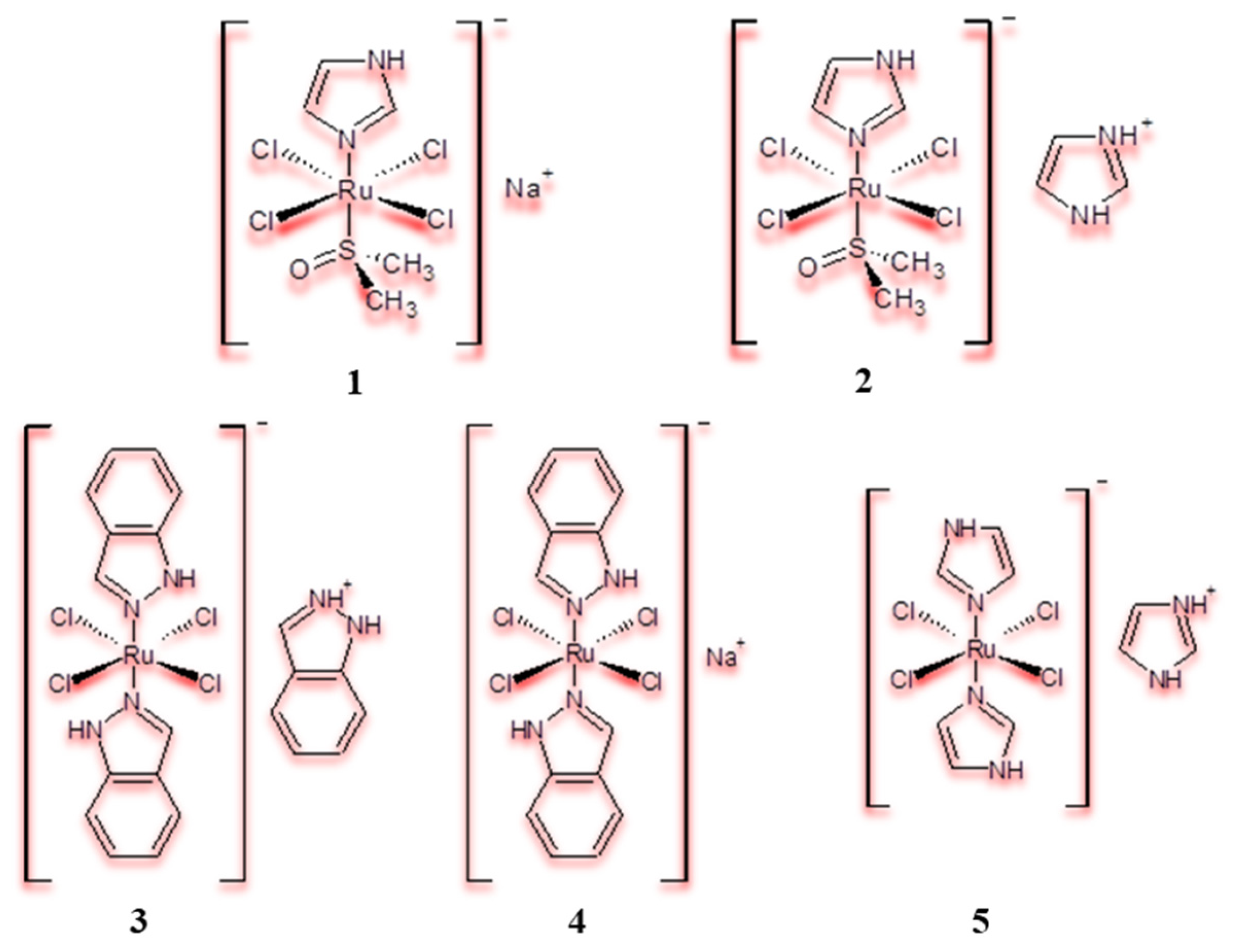

2.1. Ru(III) Complexes as Prodrugs in Cancer Therapy

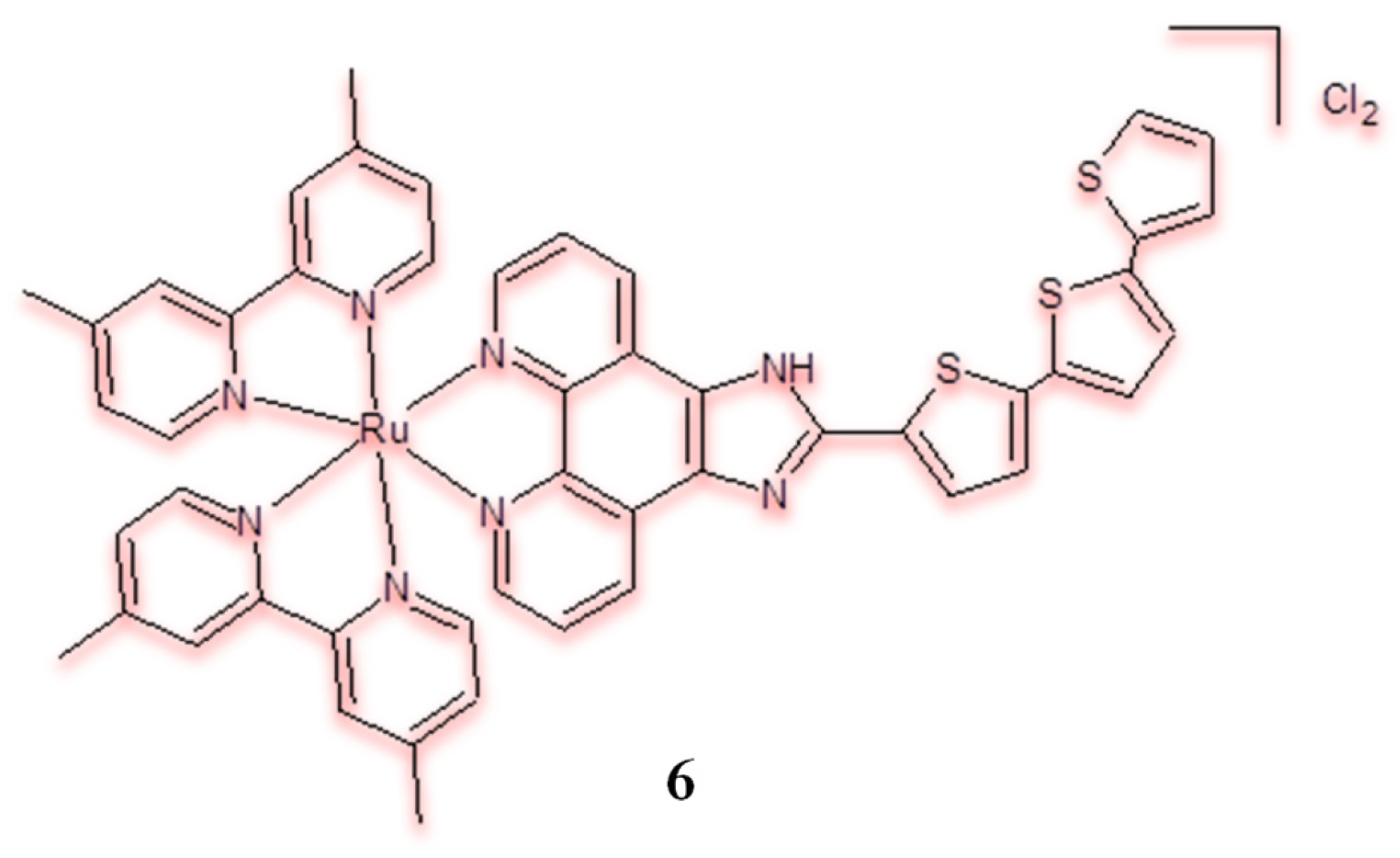

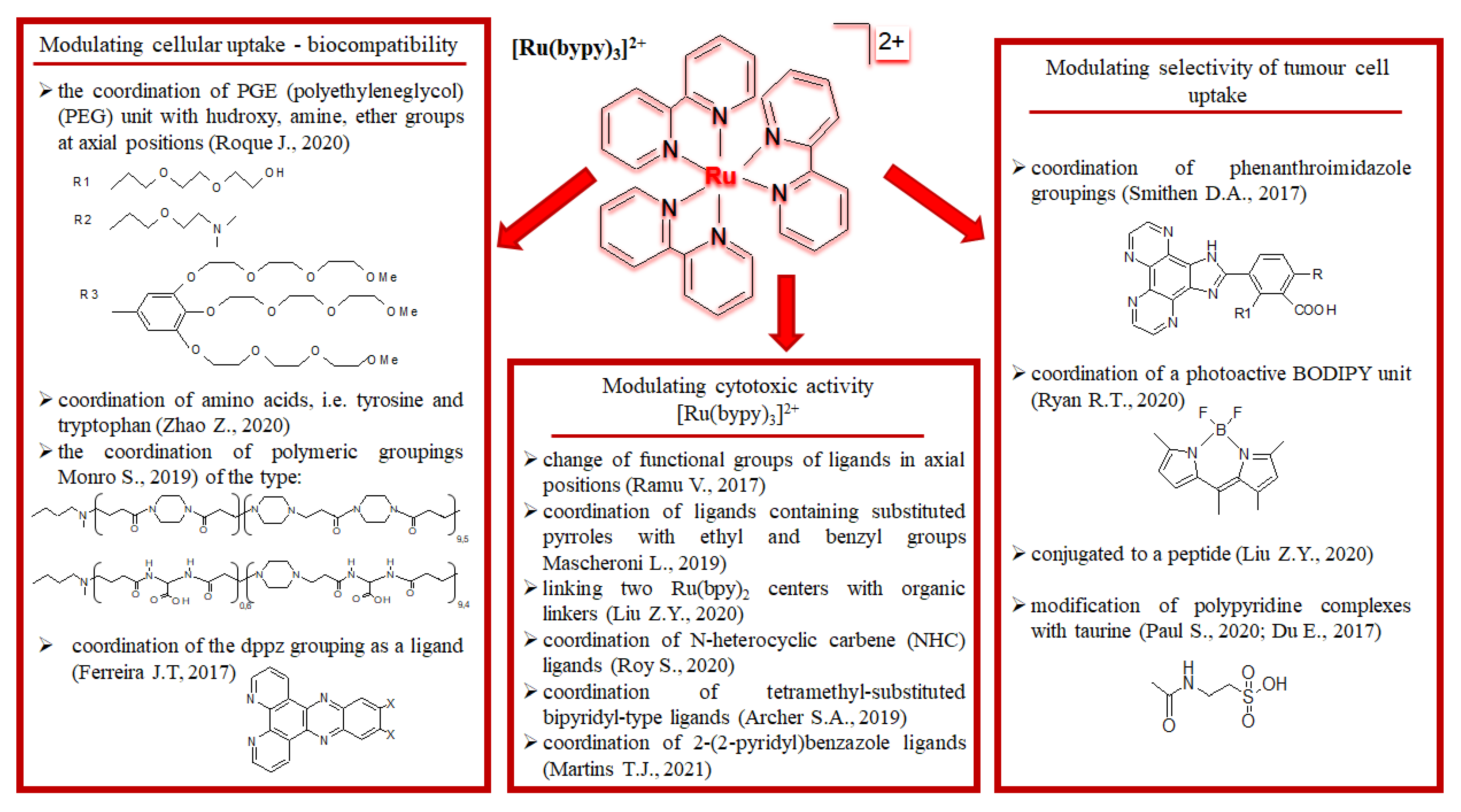

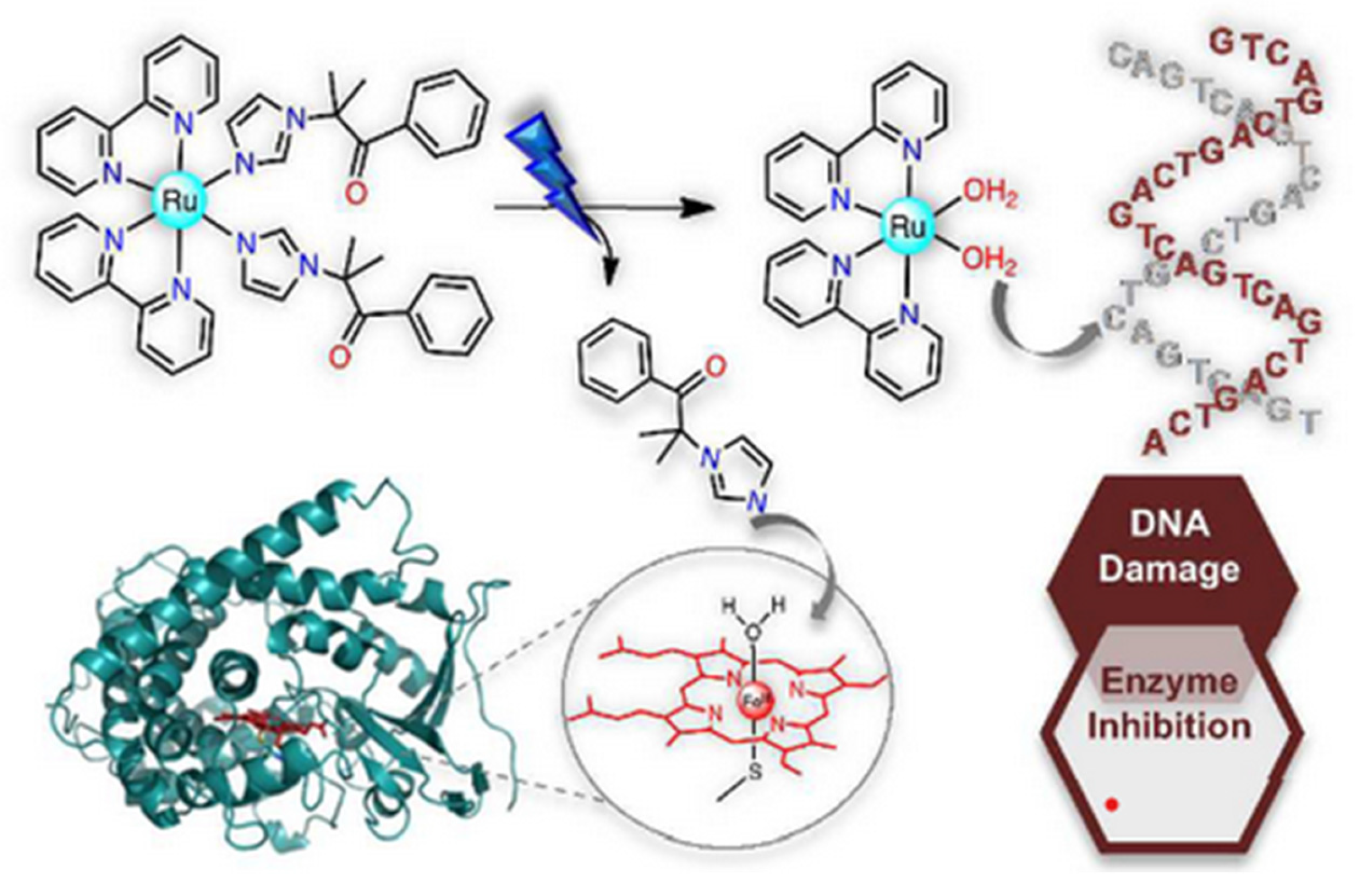

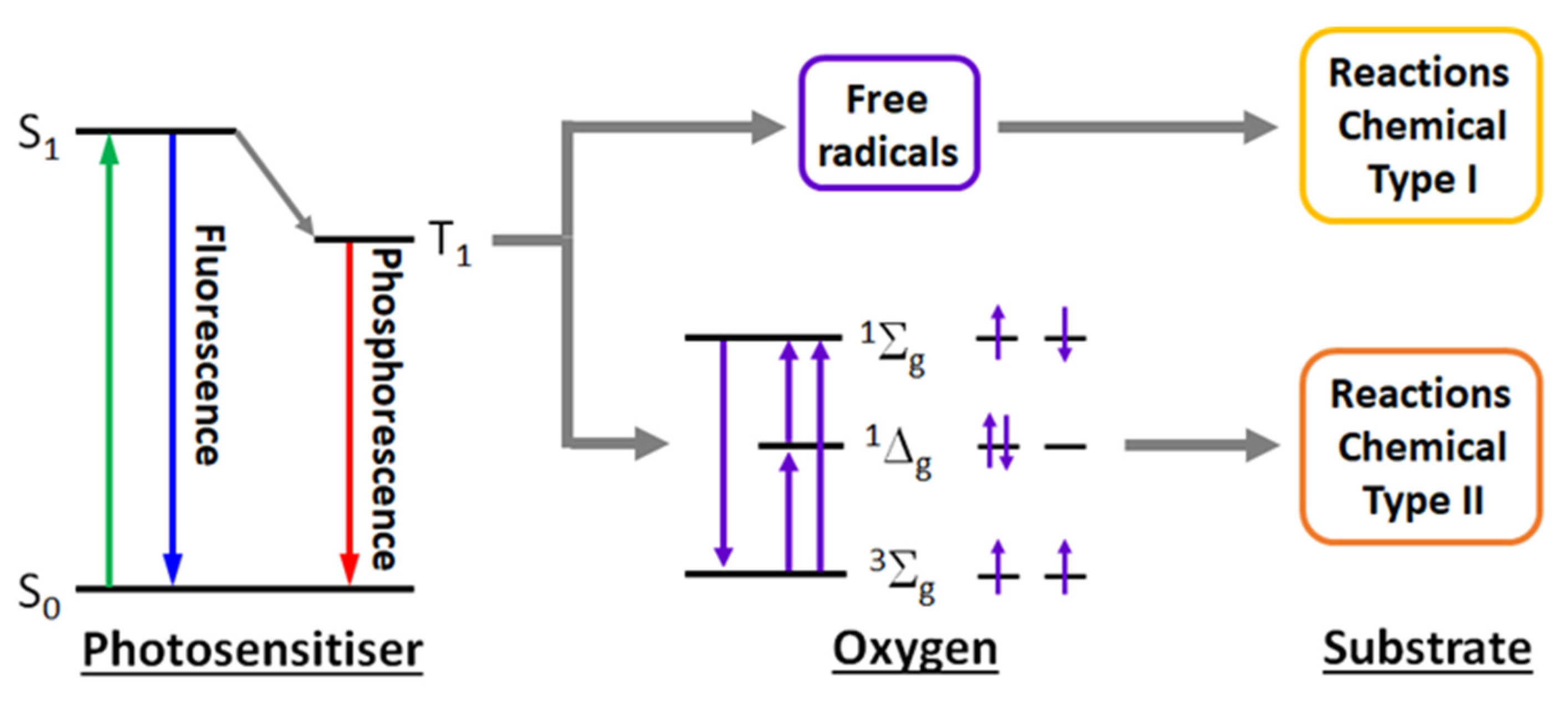

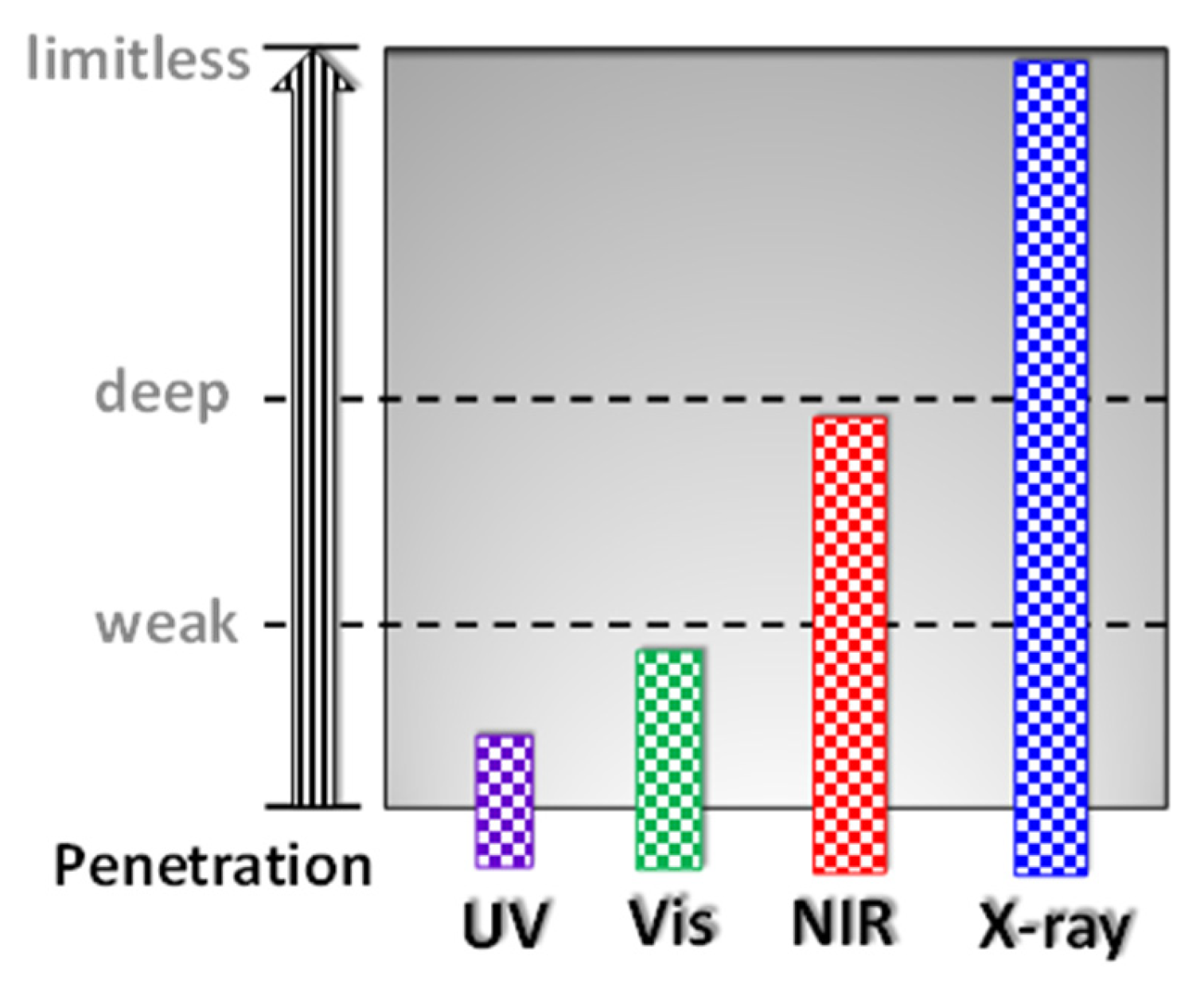

2.2. Ruthenium(II) Complexes as Sensitisers in PDT and PACT Therapy

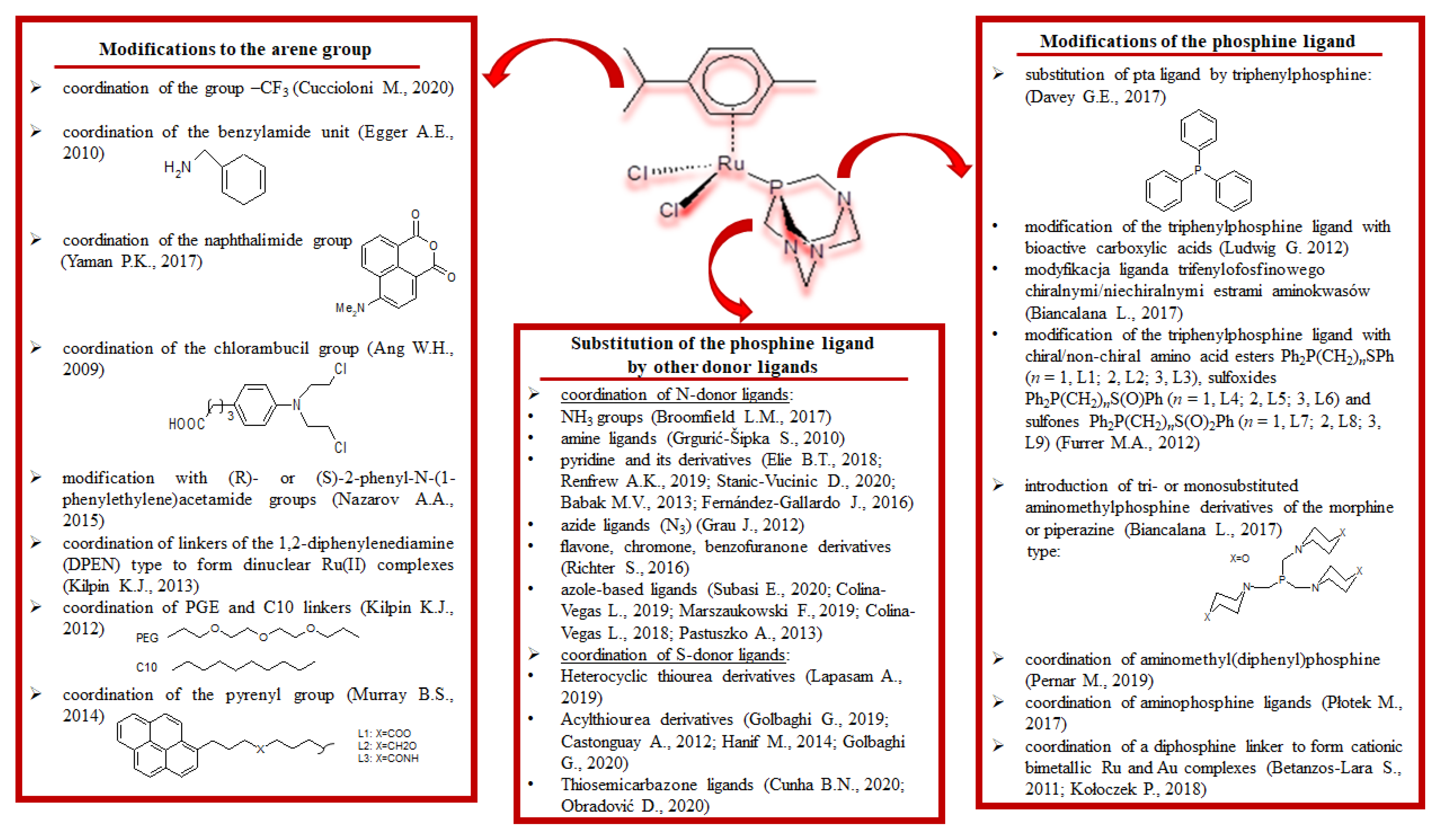

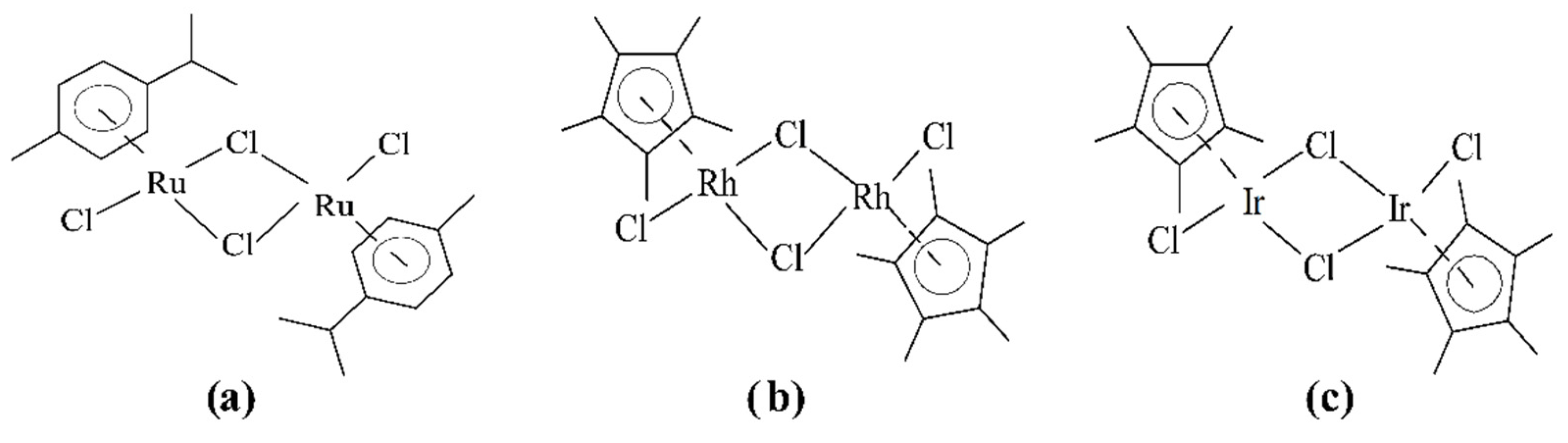

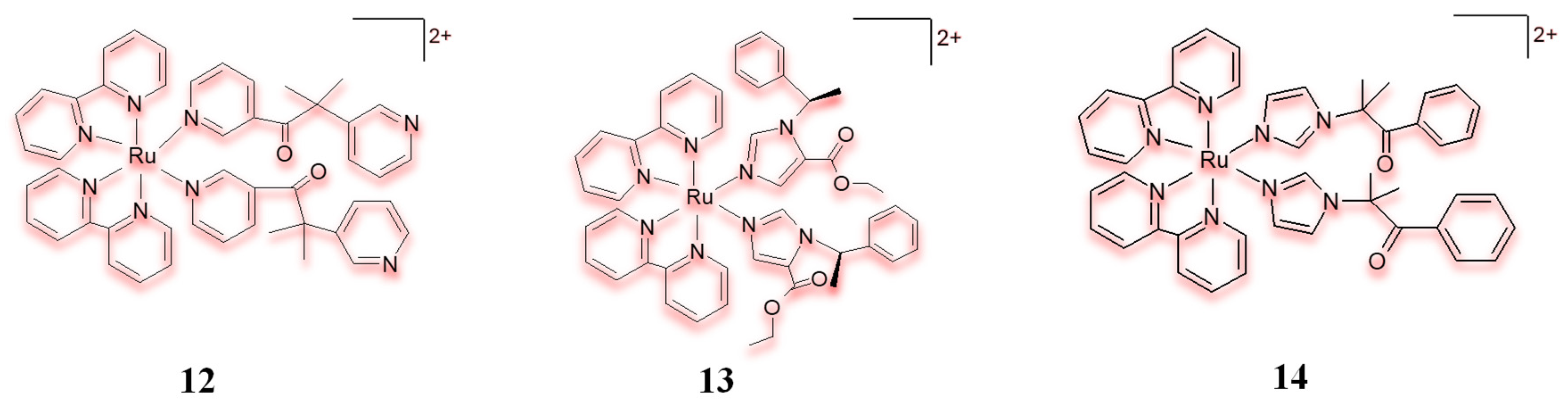

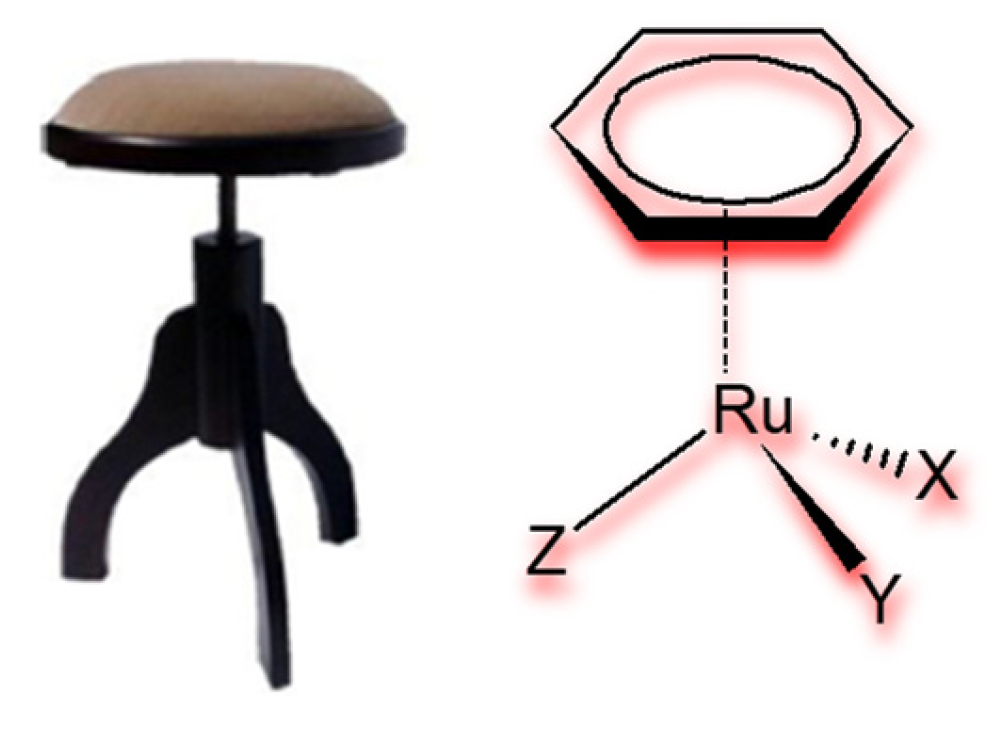

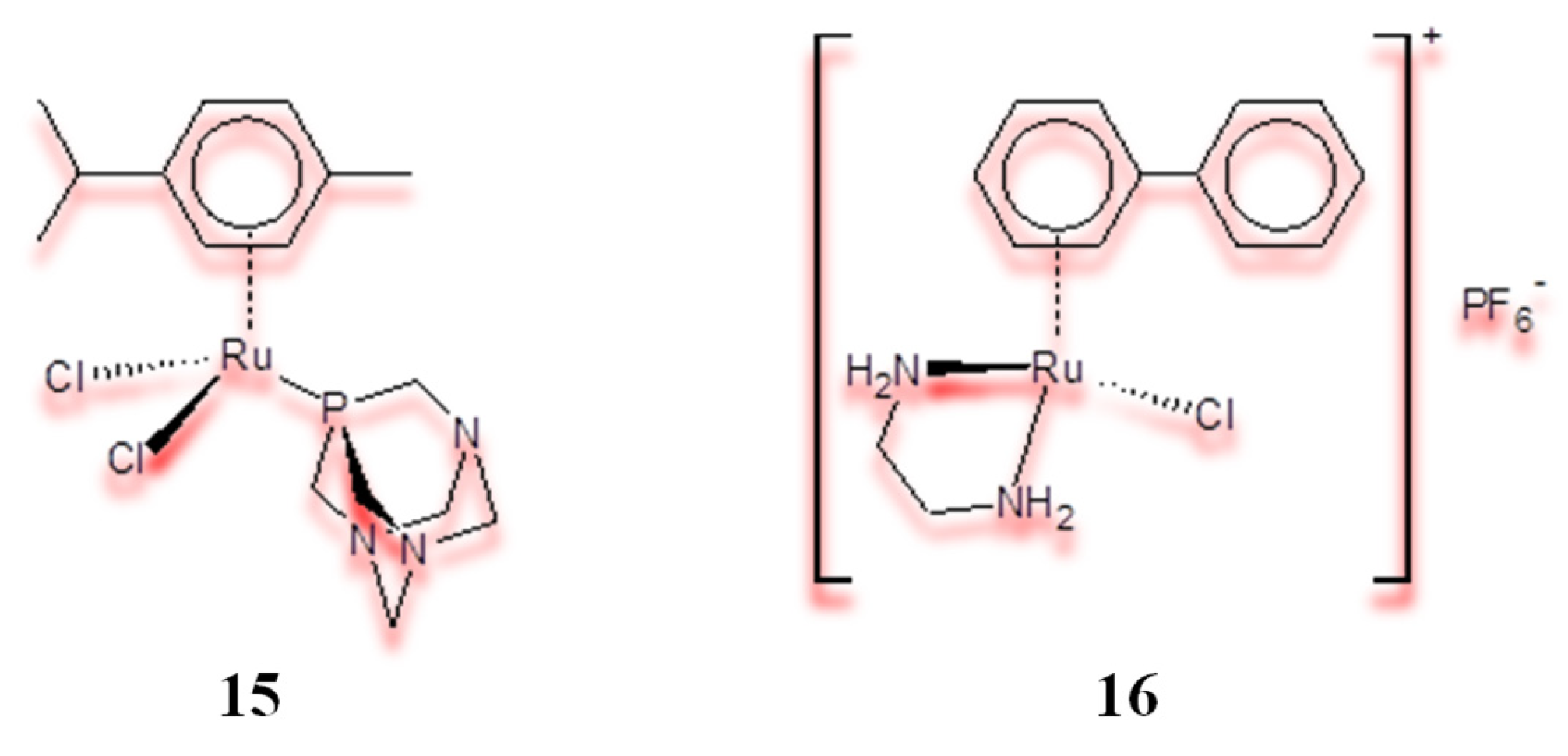

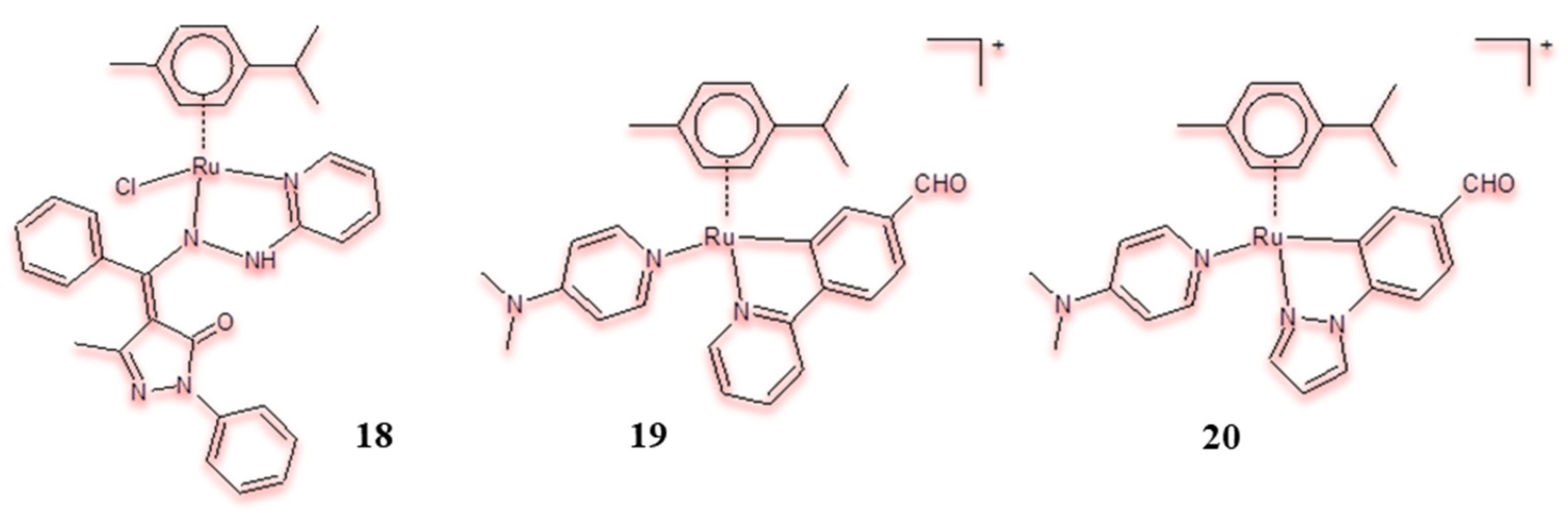

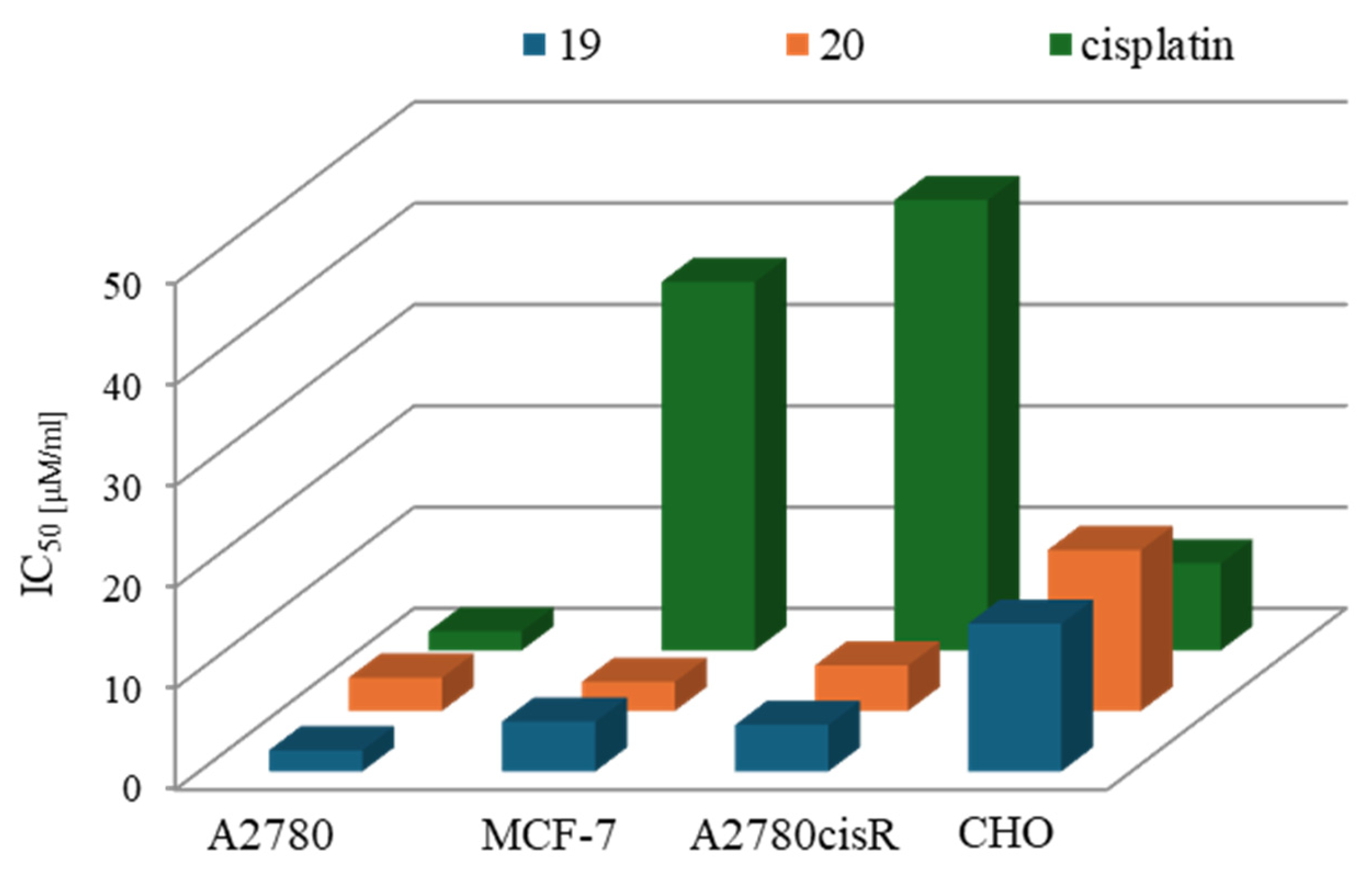

2.3. Half-Sandwich Ru(II) Complexes and the Influence of Organic Ligand Modification on Cytotoxicity

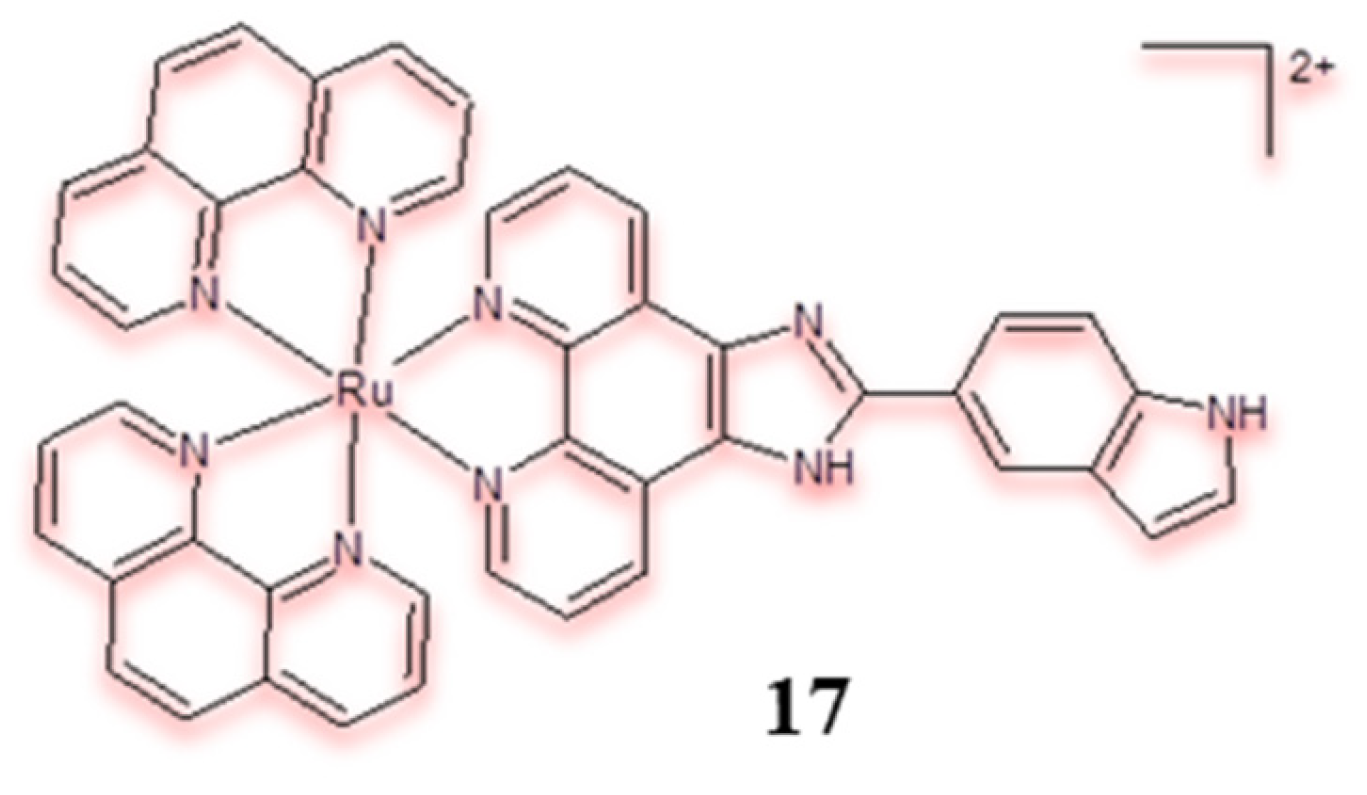

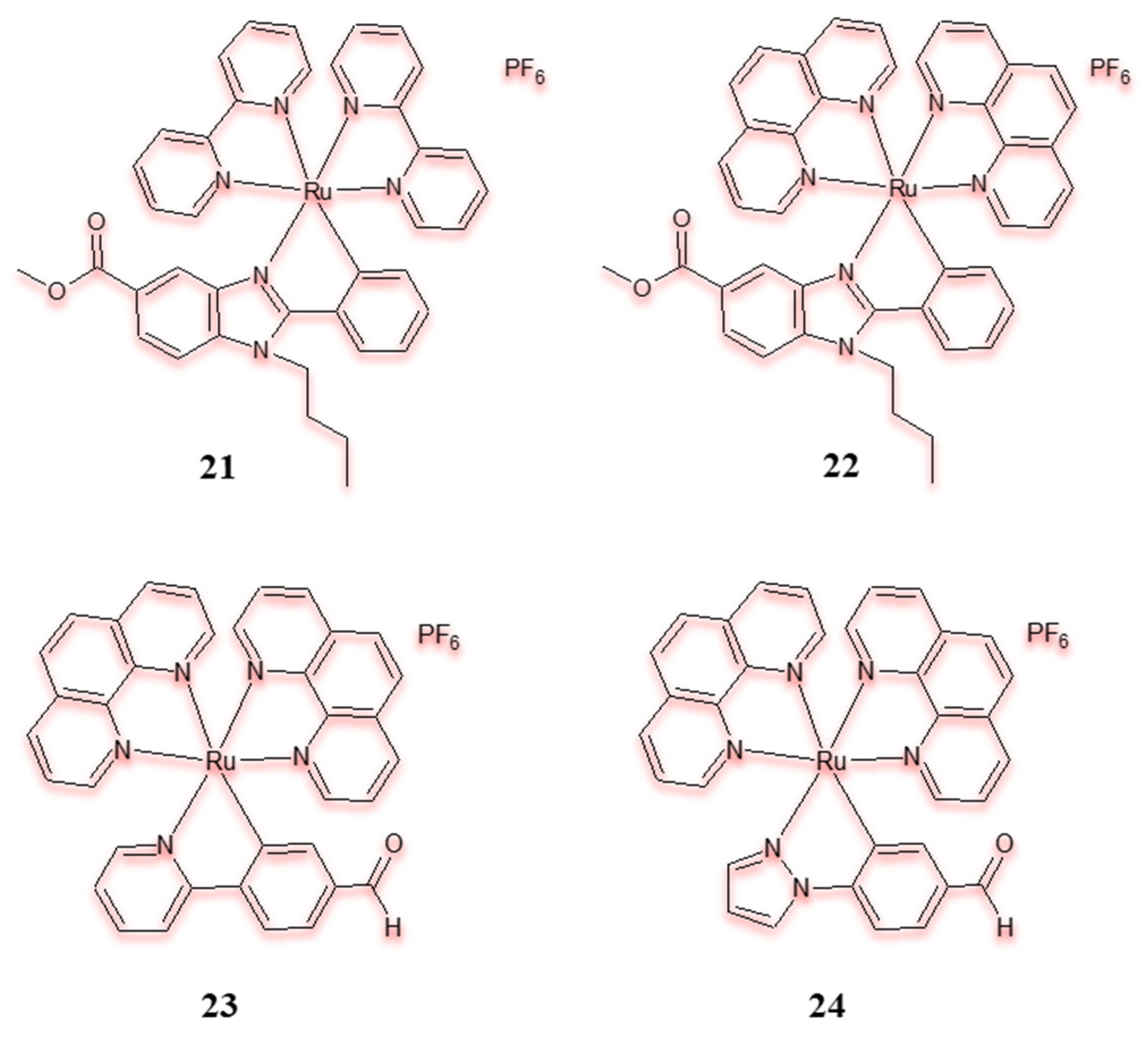

2.4. Ruthenium(II) Complexes Act on More than One Biological Target (Multiple Targets)

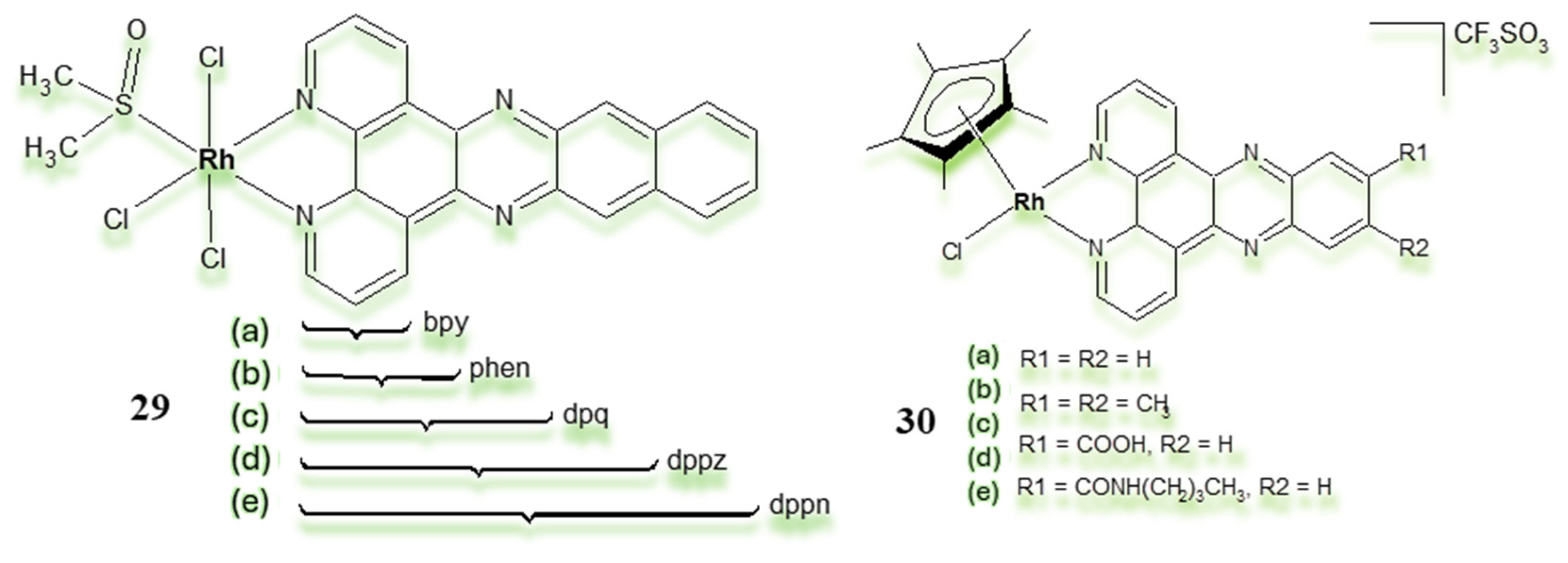

3. Potential Rhodium-Based Chemotherapeutics

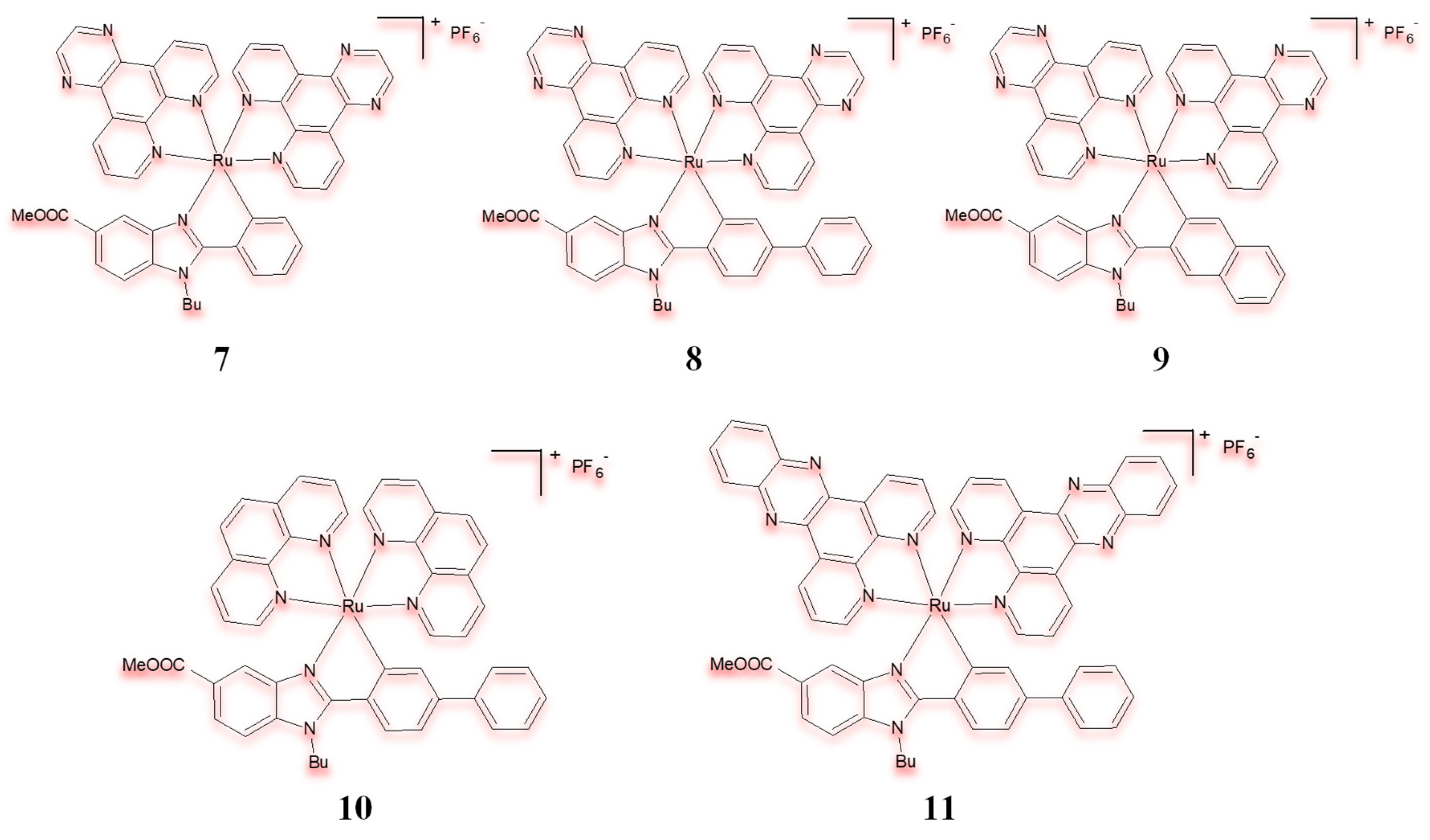

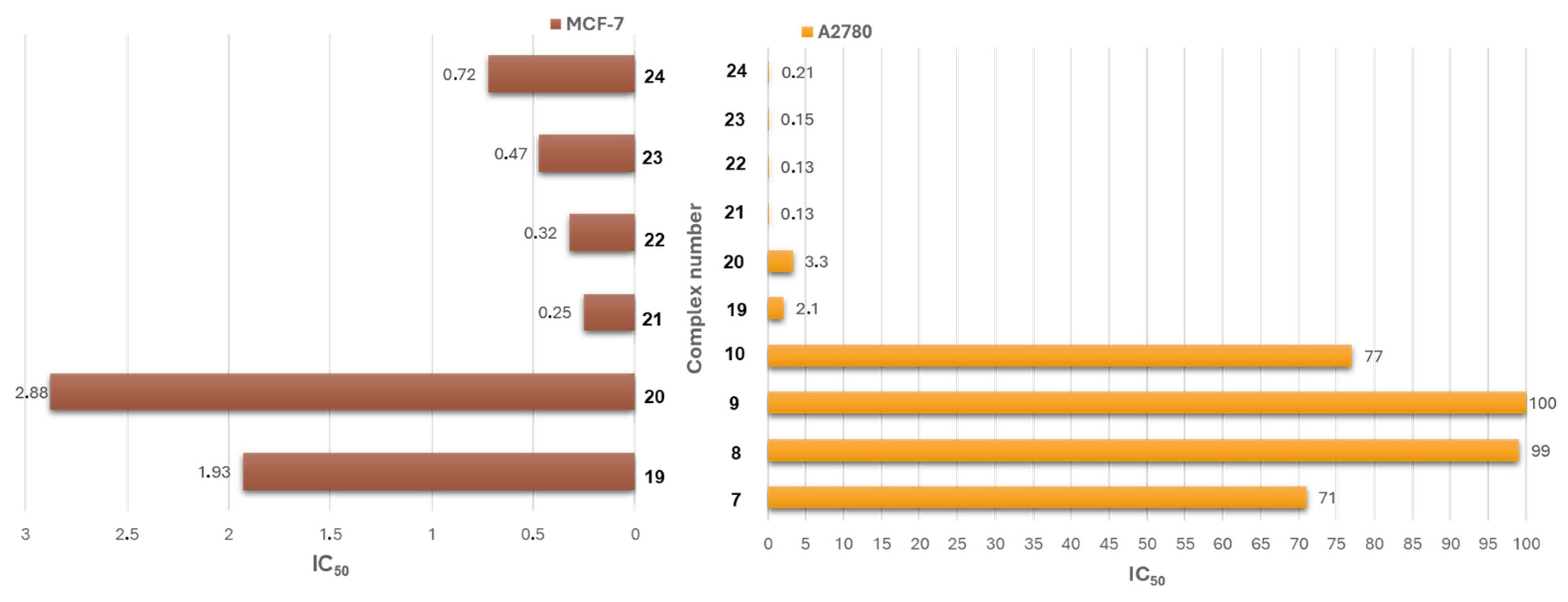

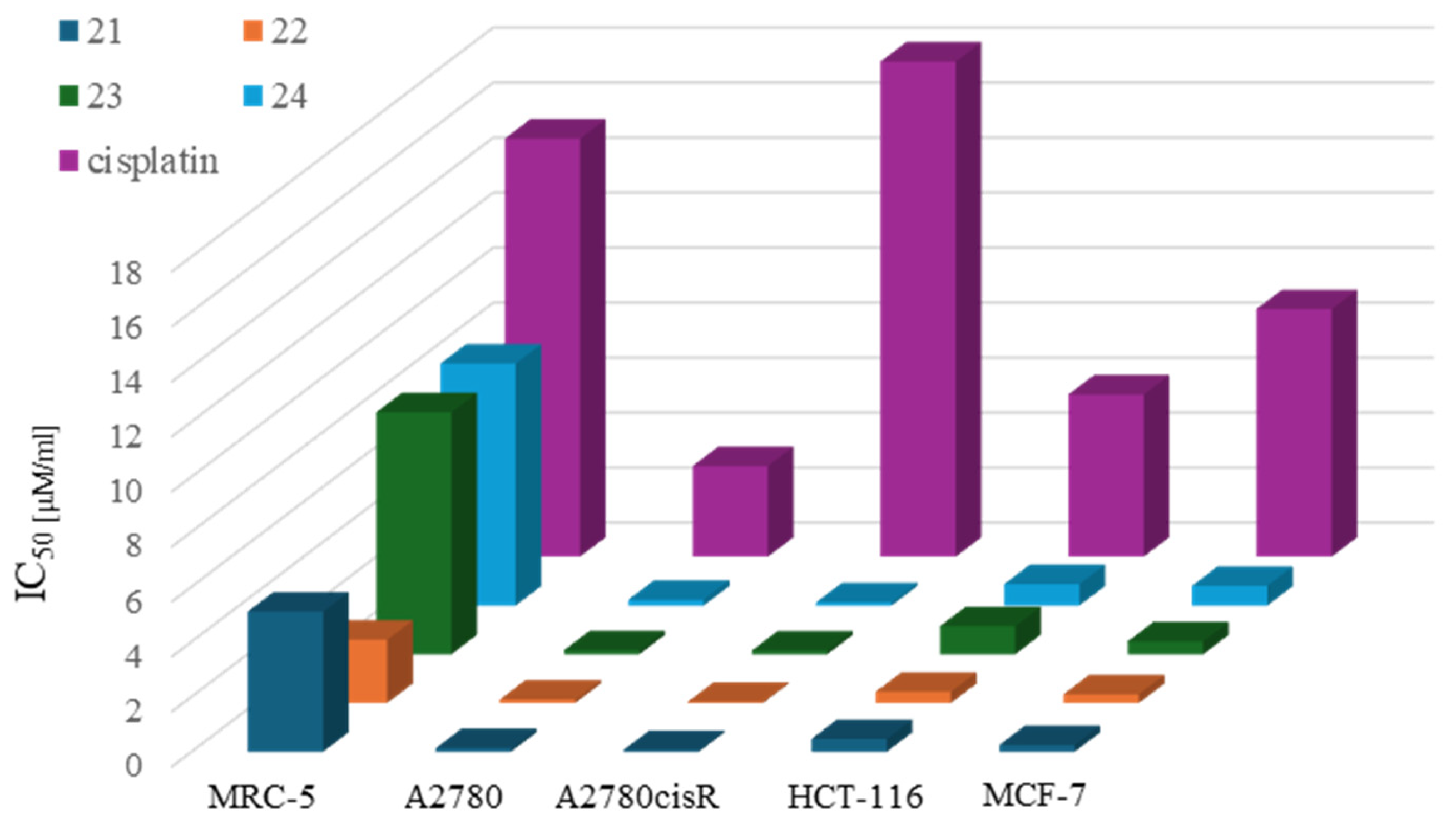

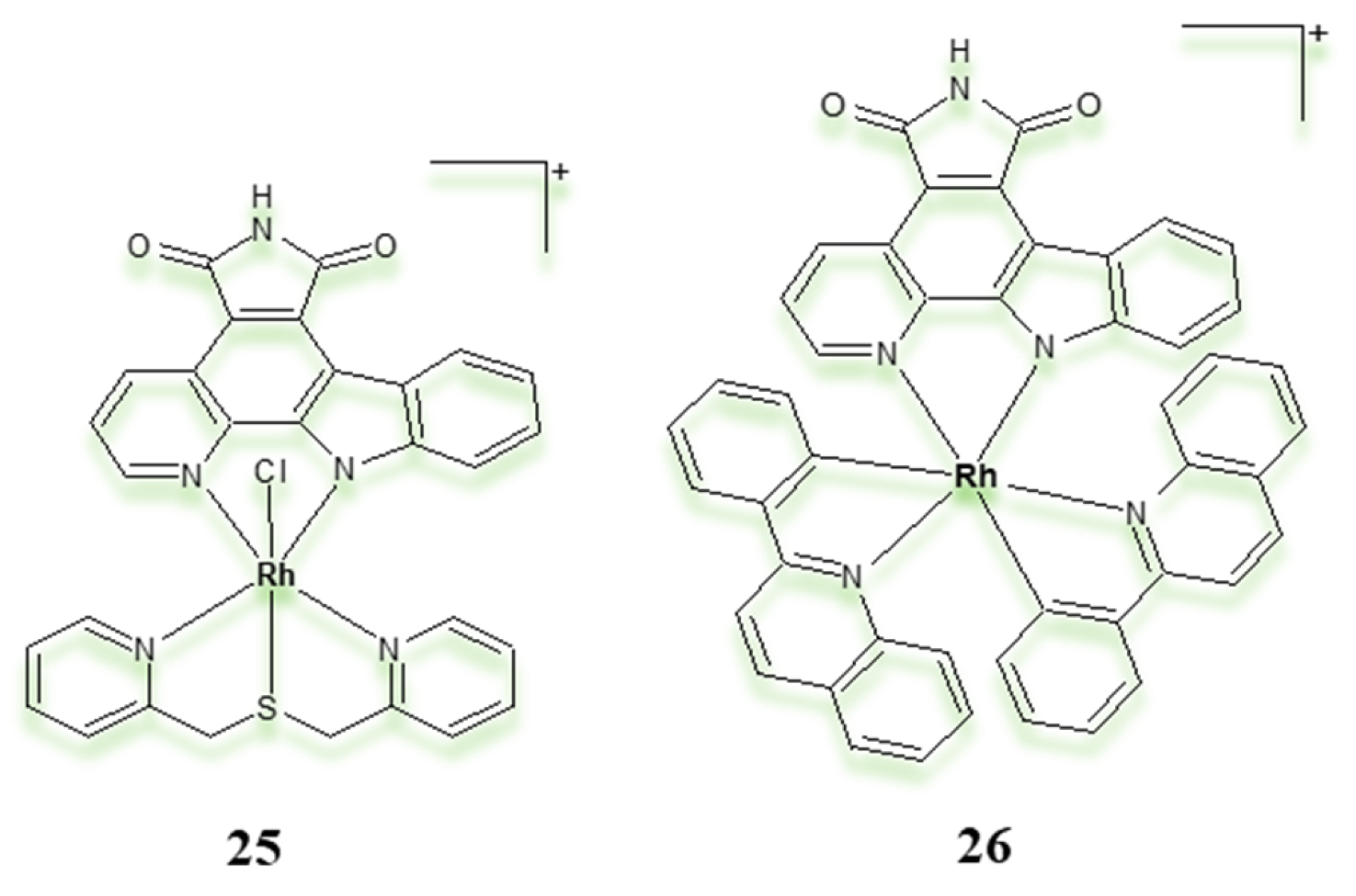

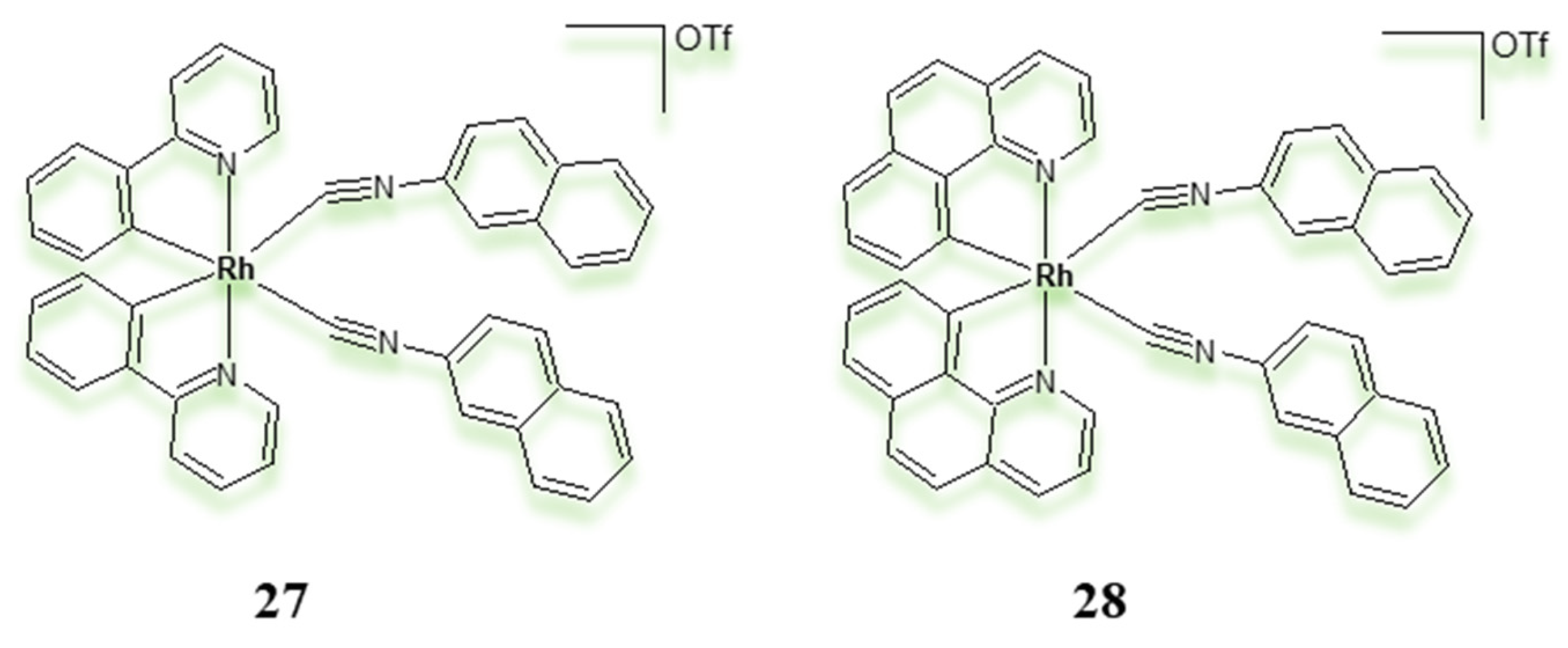

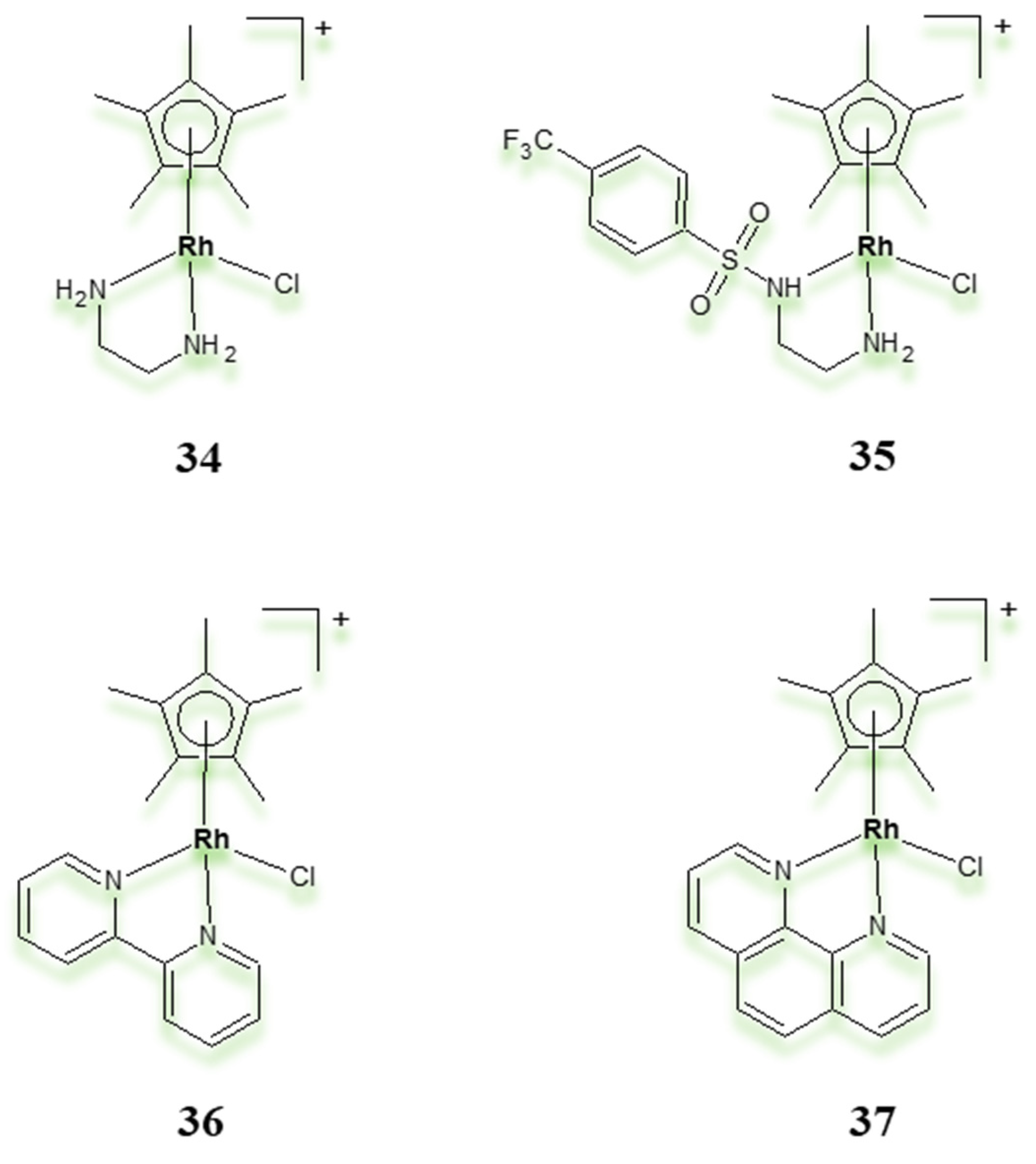

3.1. Rh(III) Complexes in Which the Metal Has a Structural Function

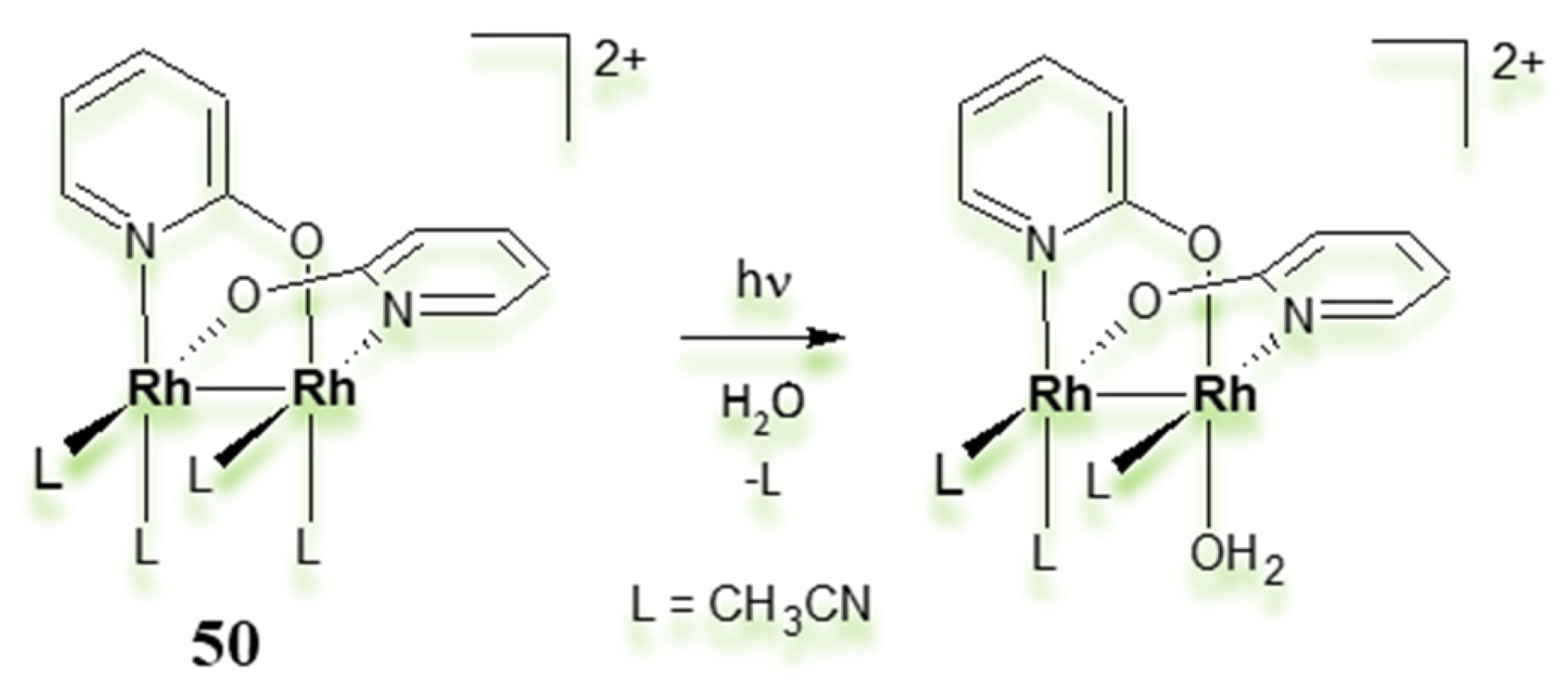

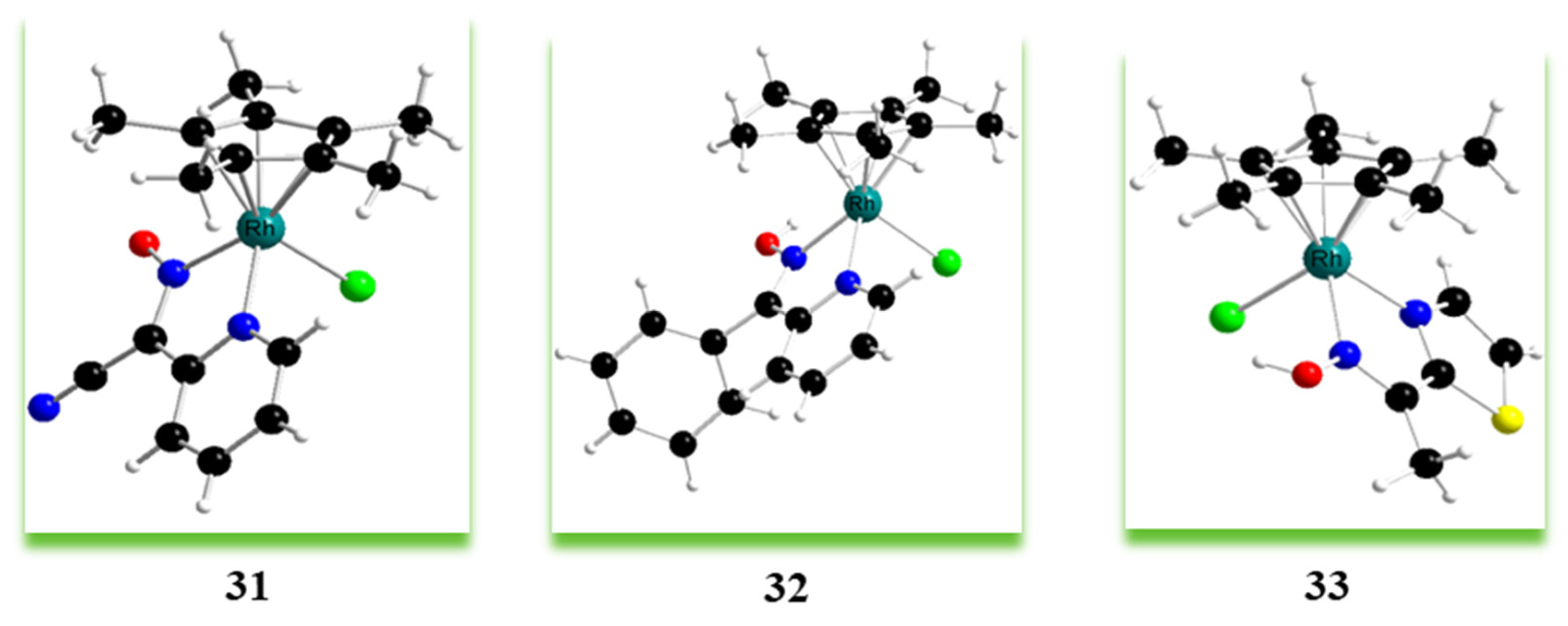

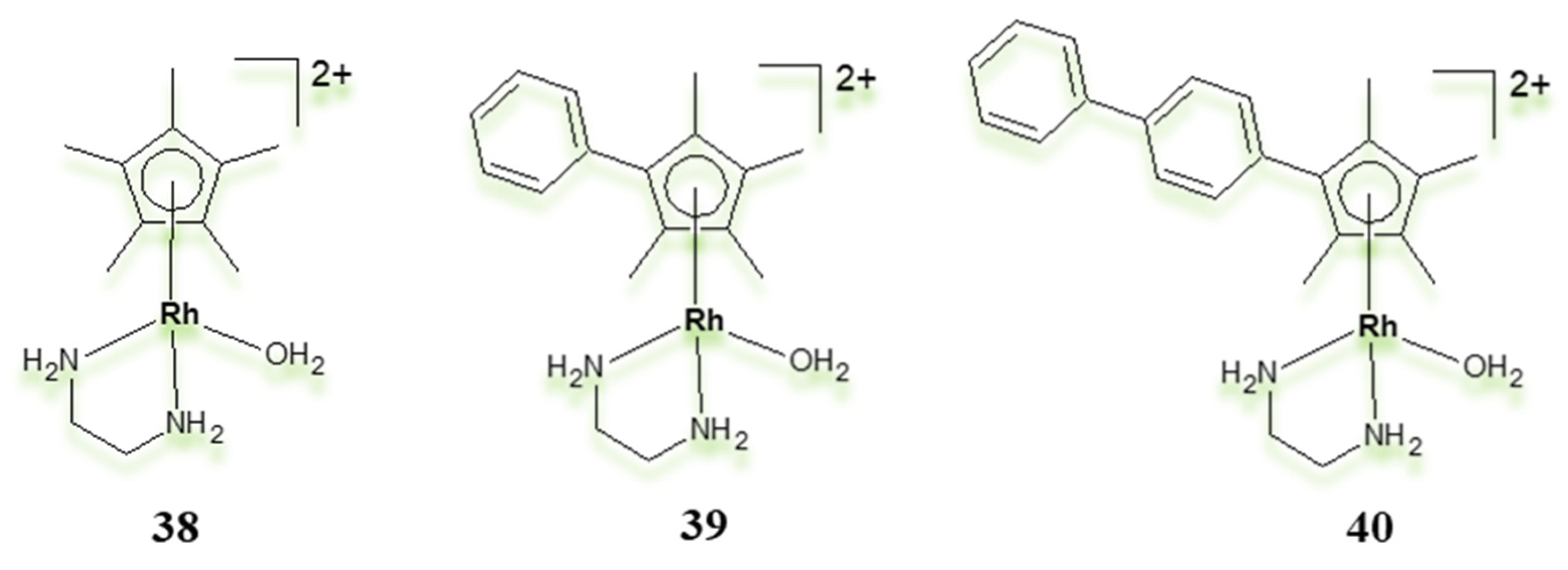

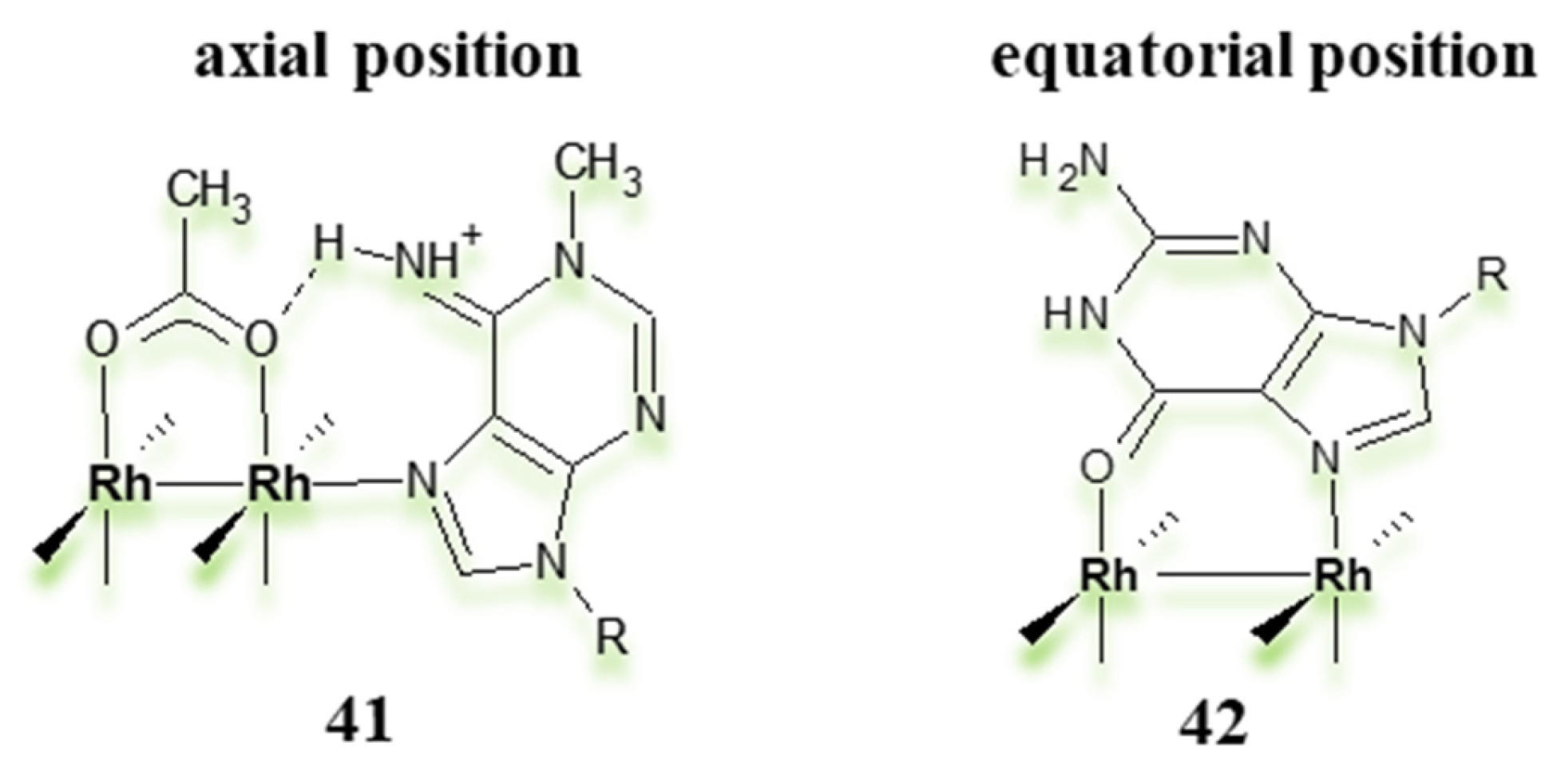

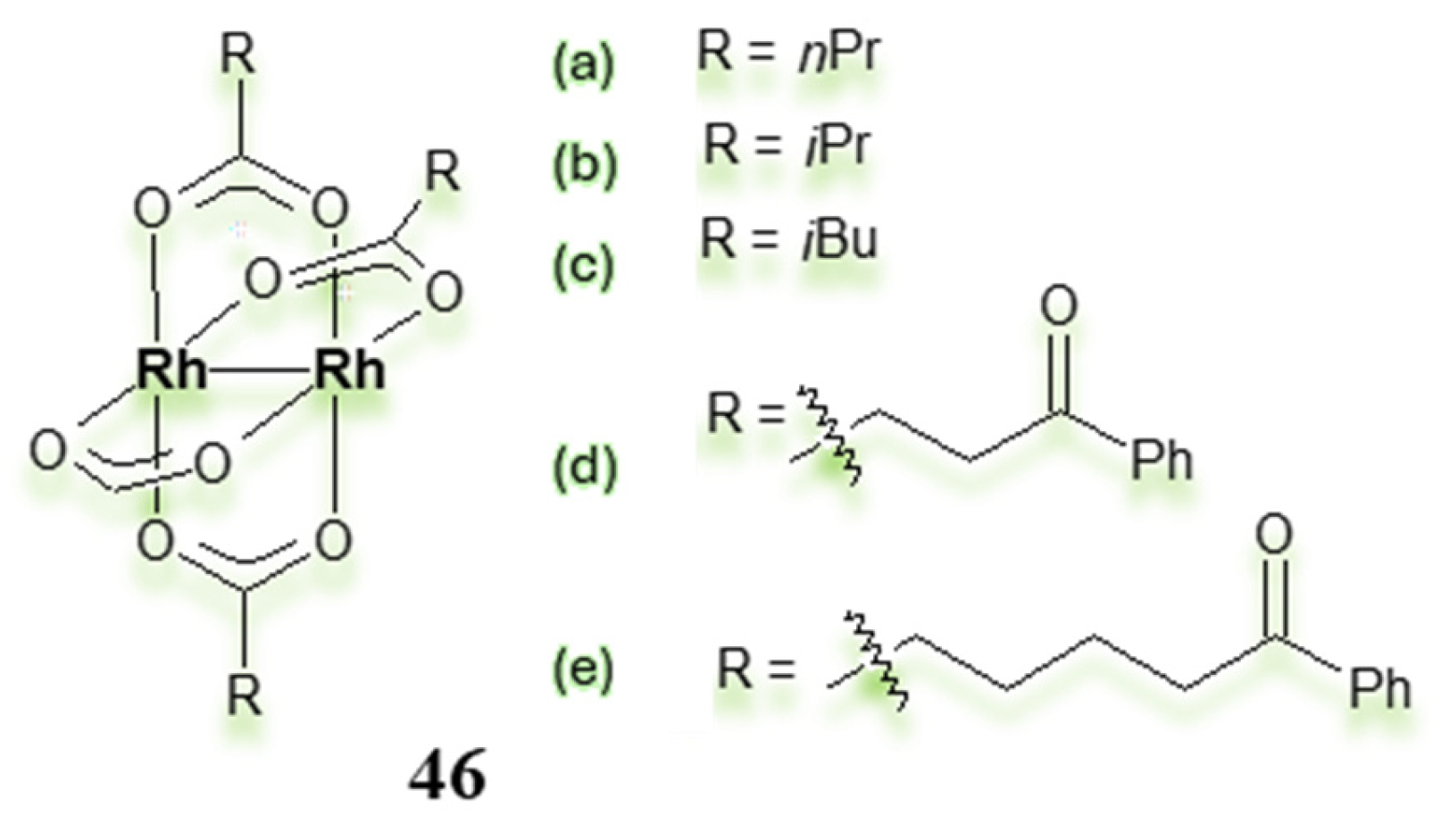

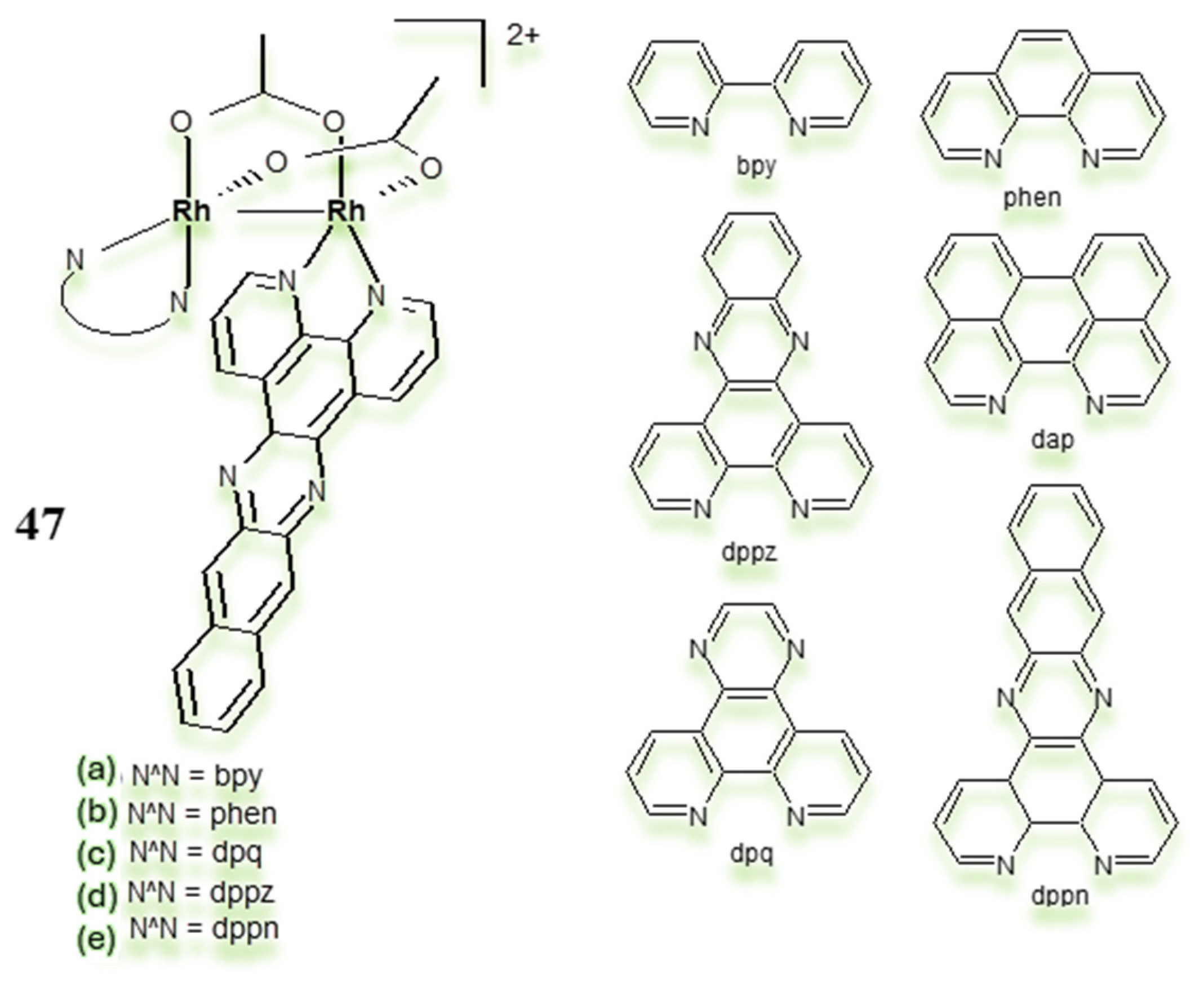

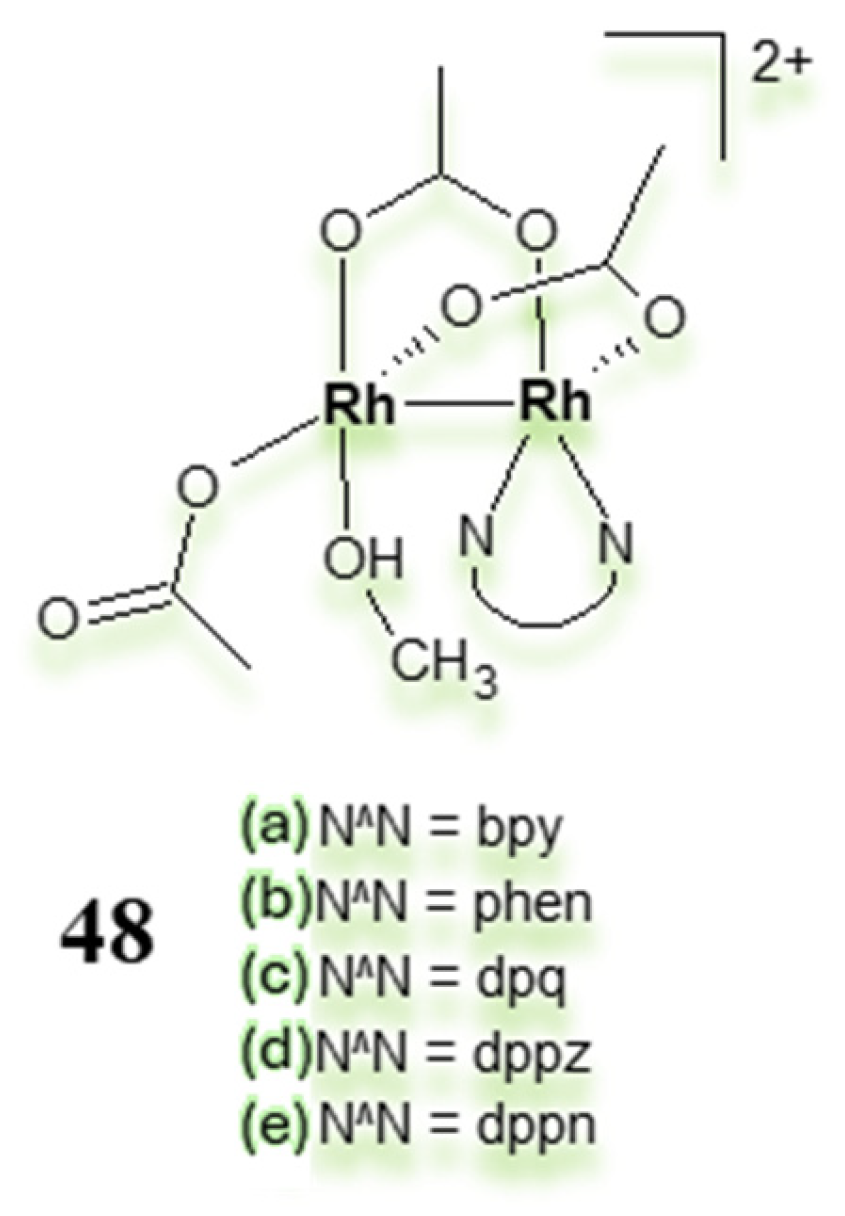

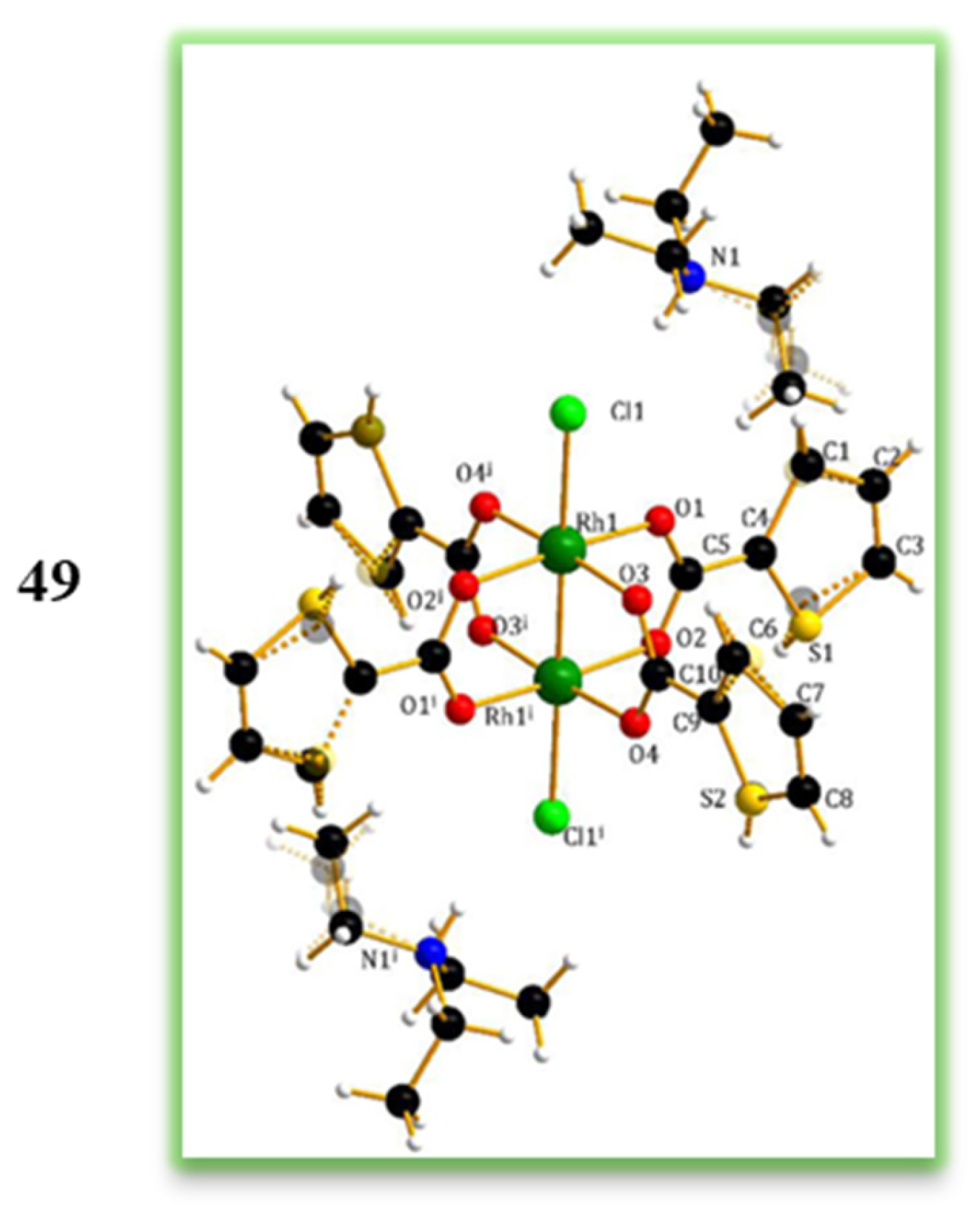

3.2. Dimeric Rh(II) Complexes with Metal–Metal Bonds

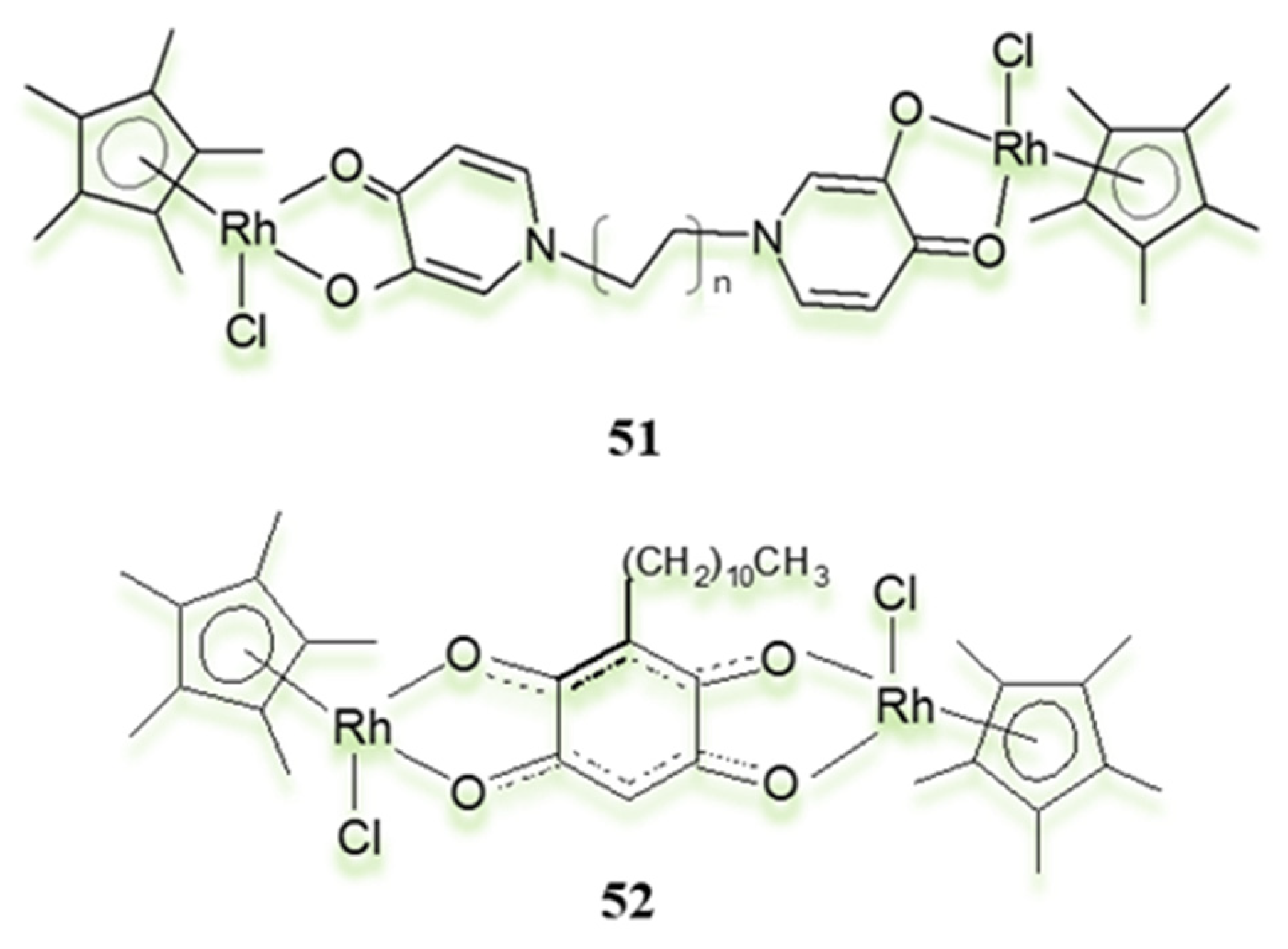

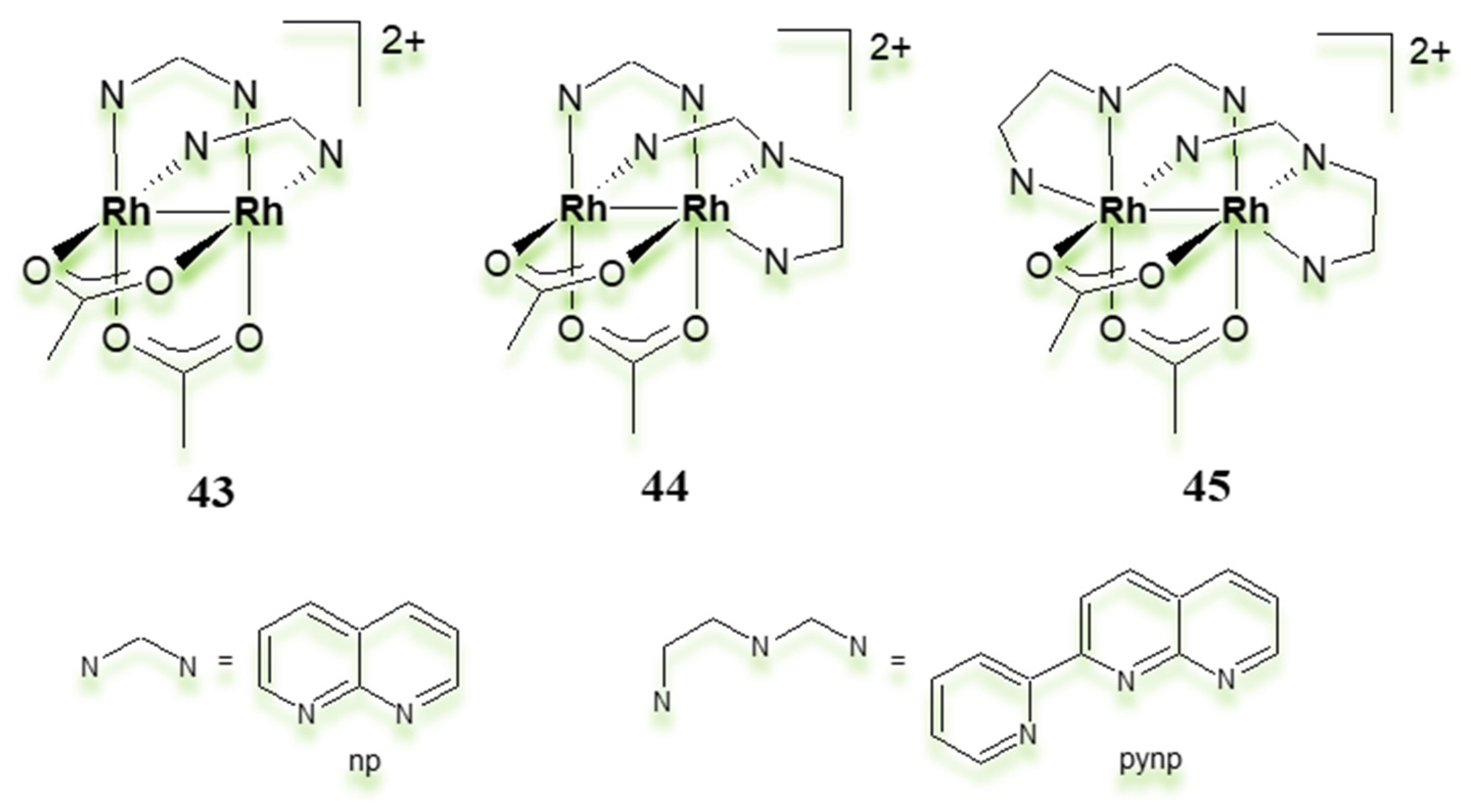

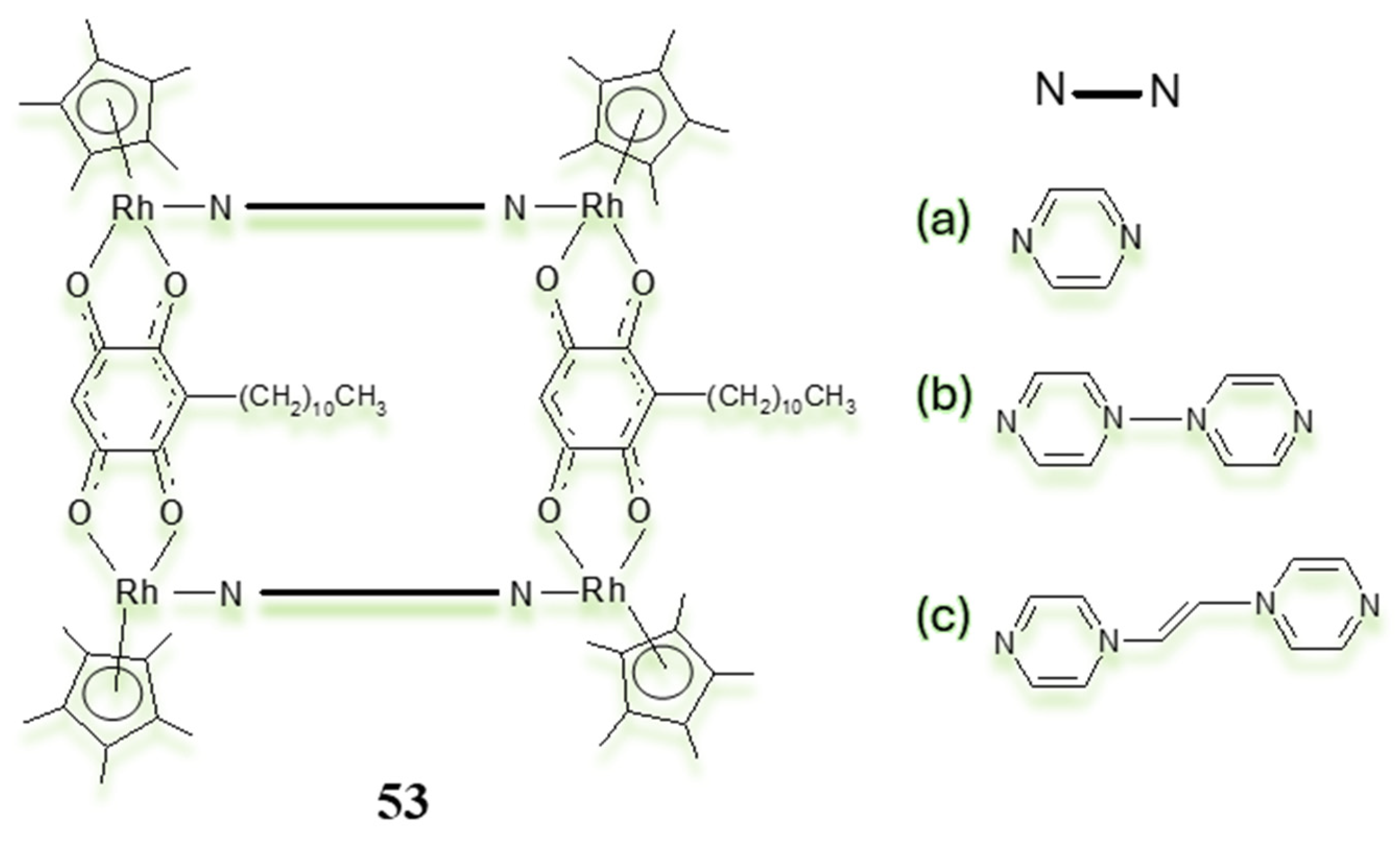

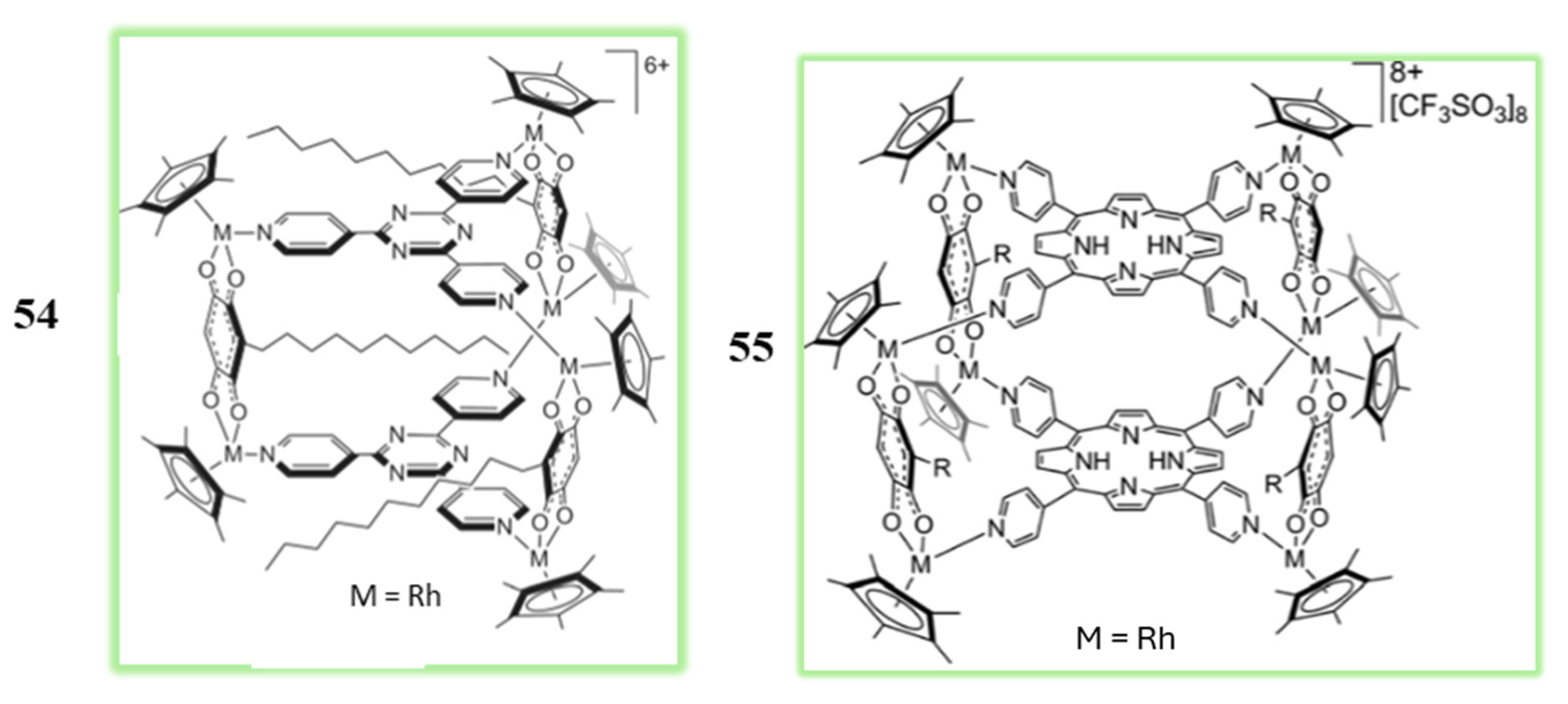

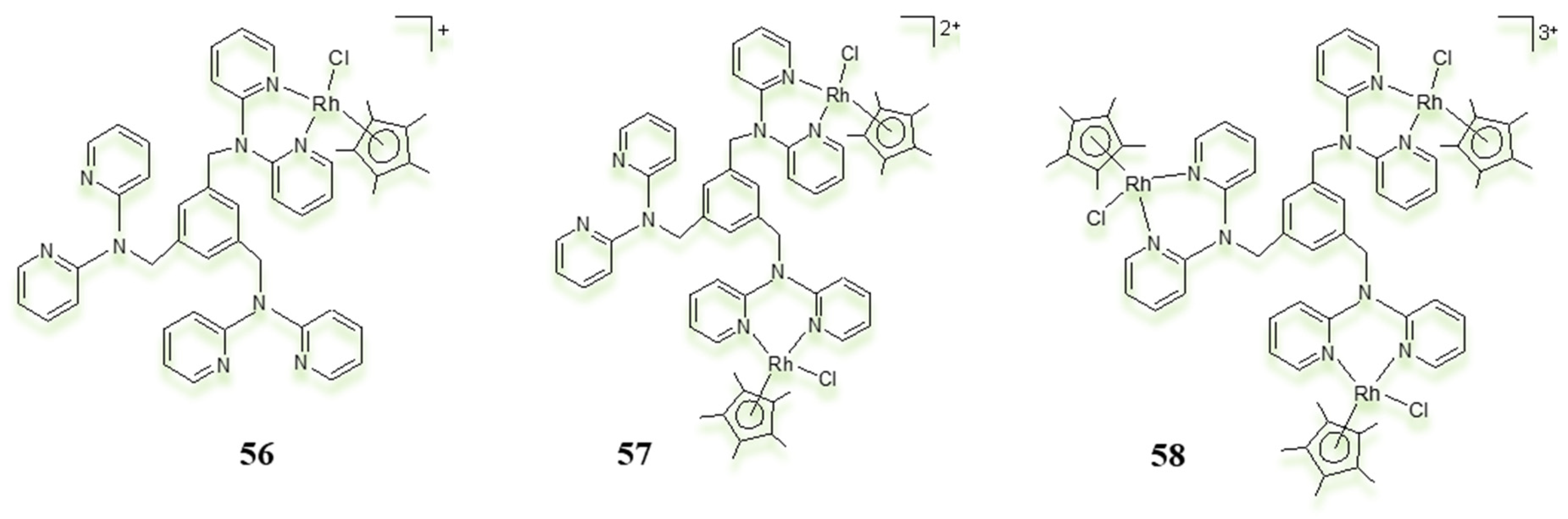

3.3. Polynuclear Ligand-Bridged Rhodium Complexes

4. Research into the Use of Iridium Complexes in Cancer Therapy

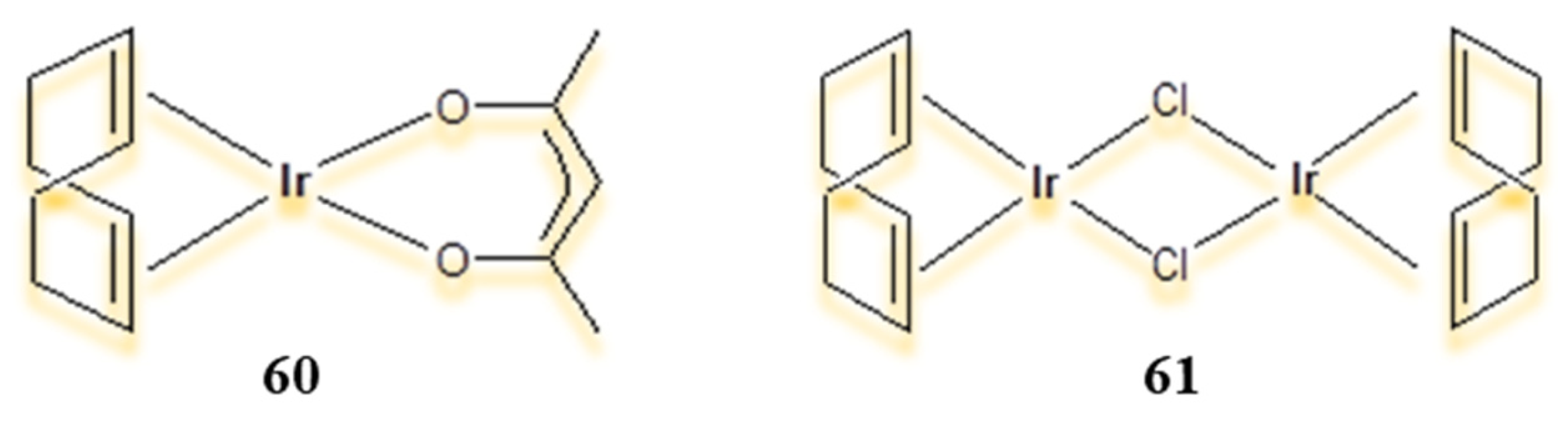

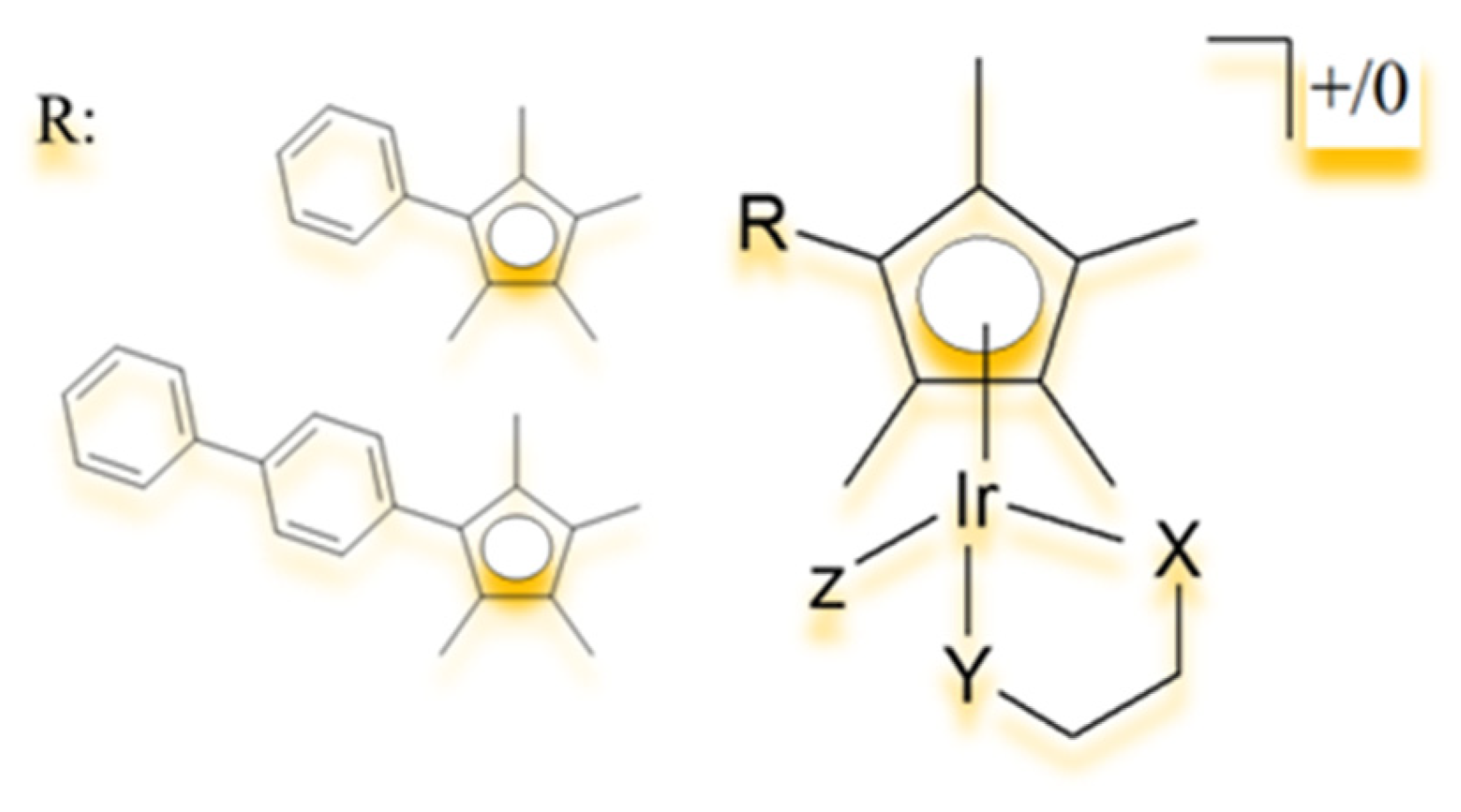

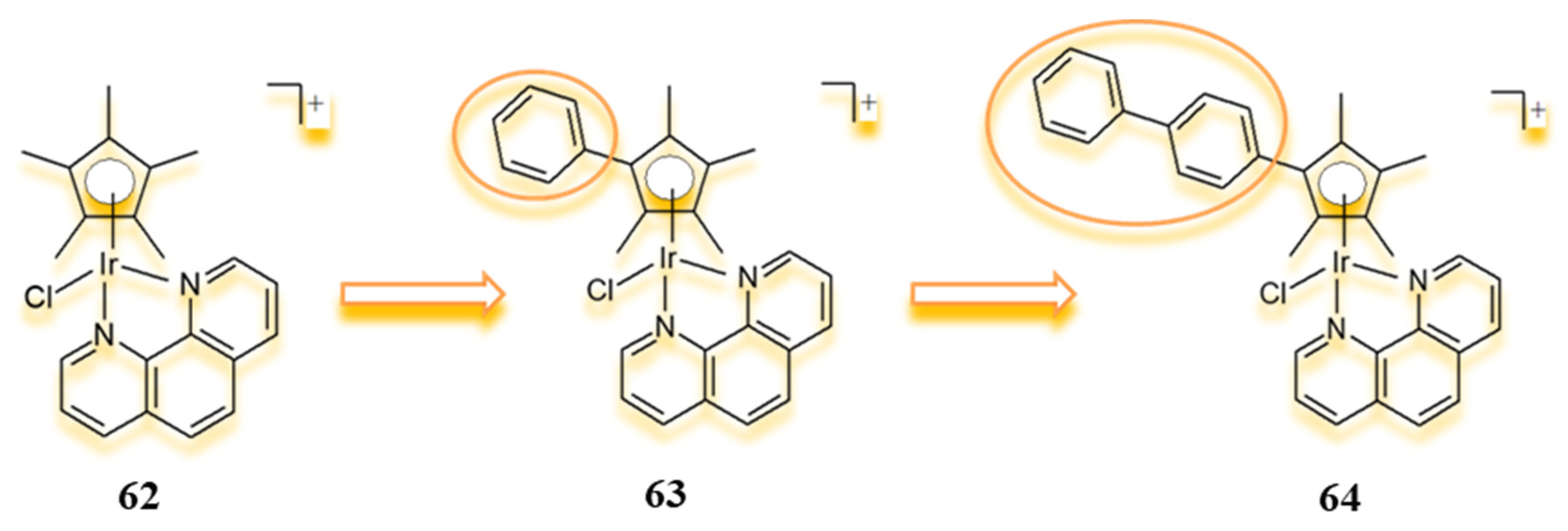

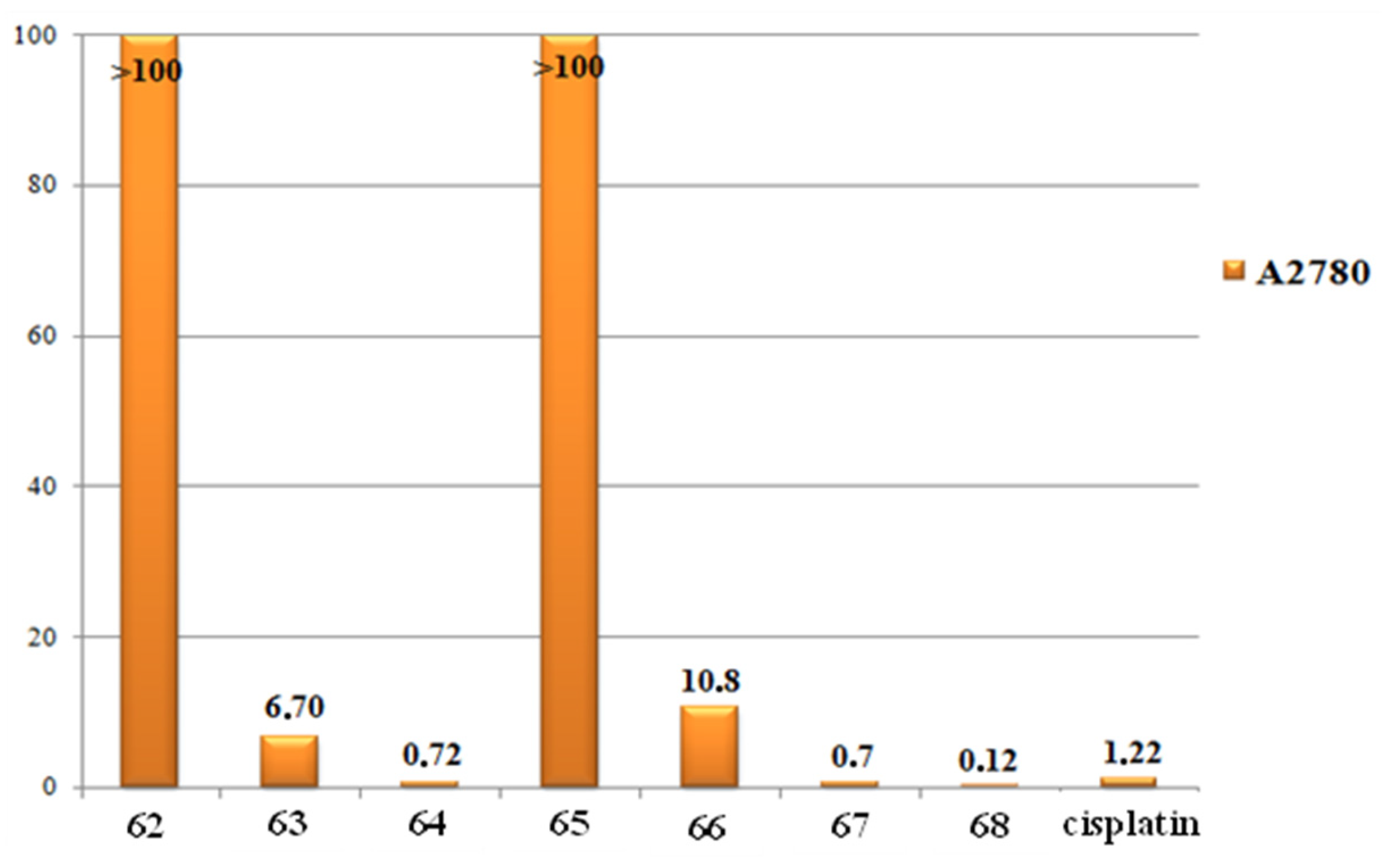

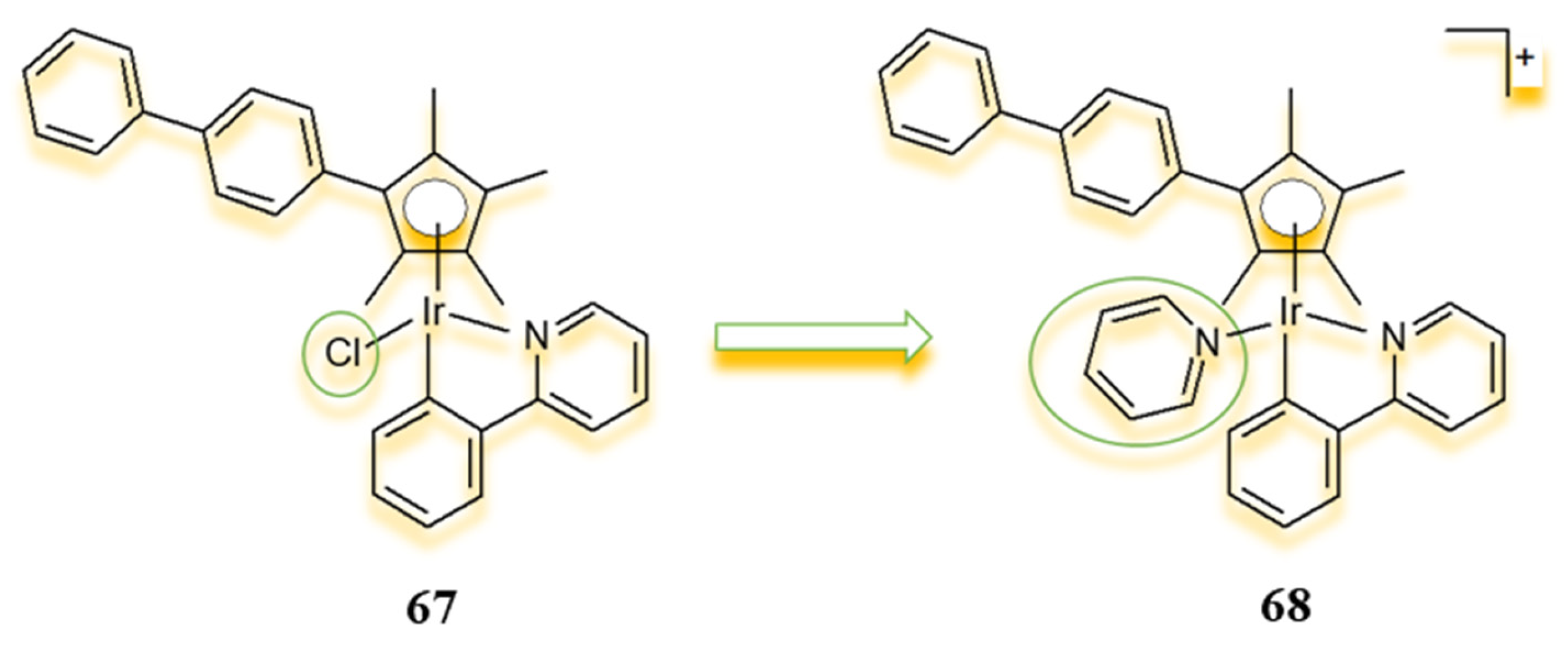

4.1. Half-Sandwich Ir(III) Complexes

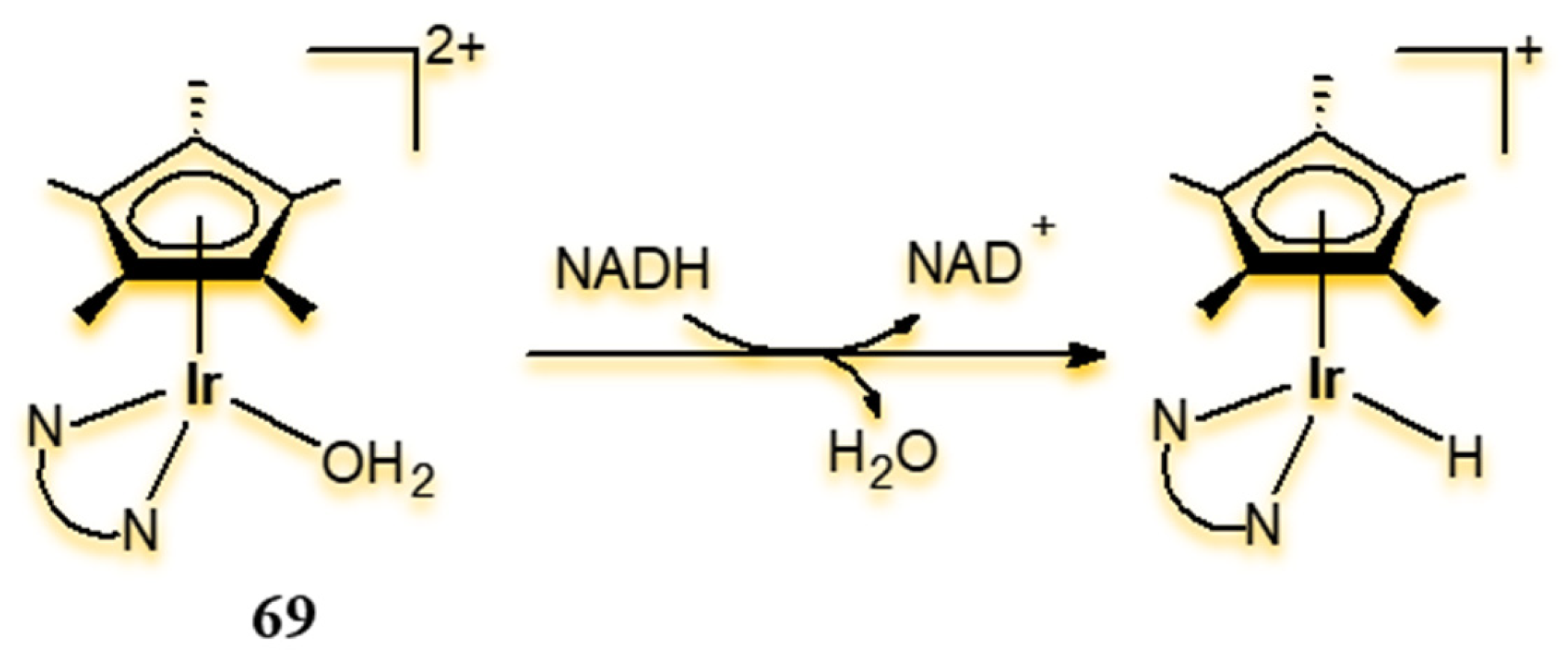

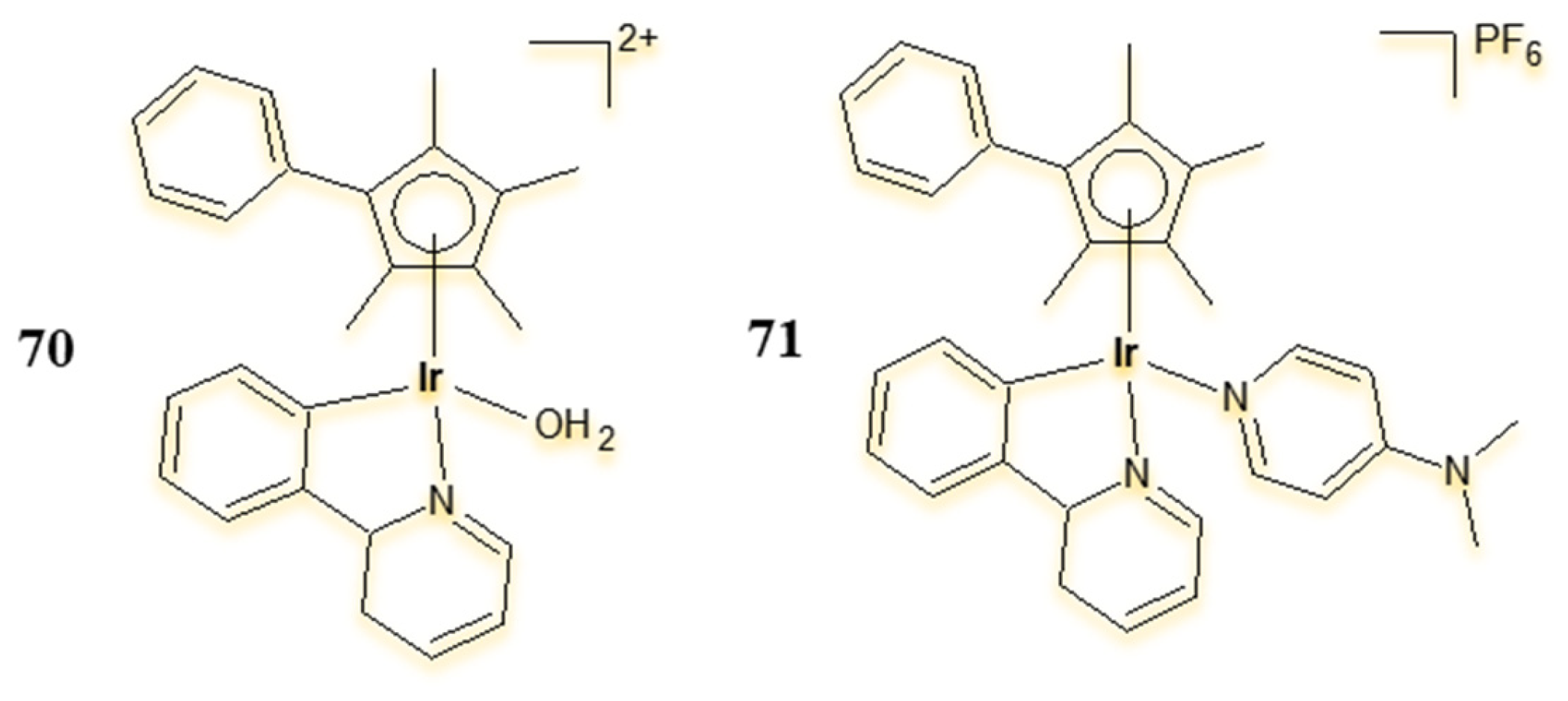

4.2. Ir(III) Complexes as Biocatalysts

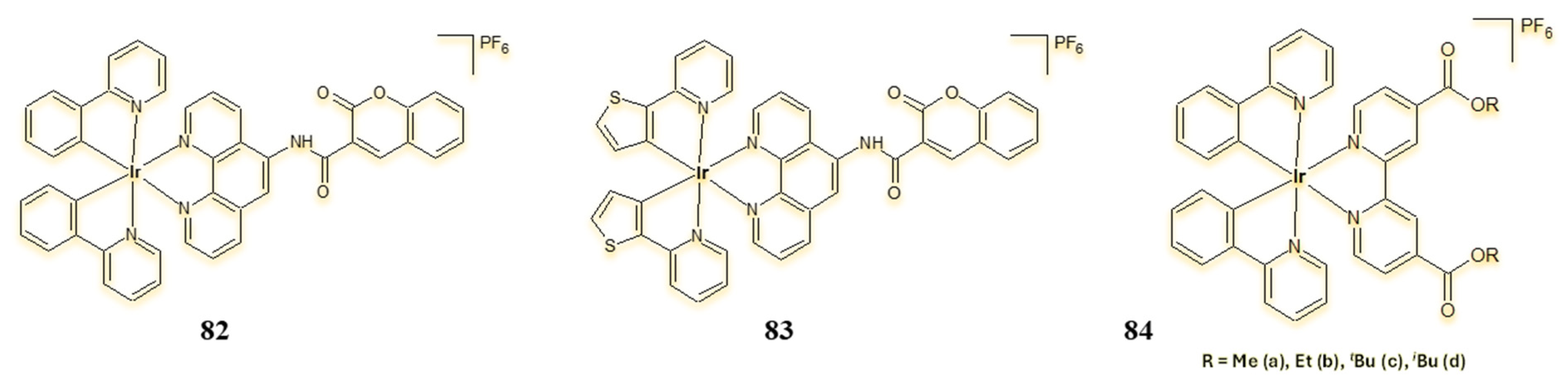

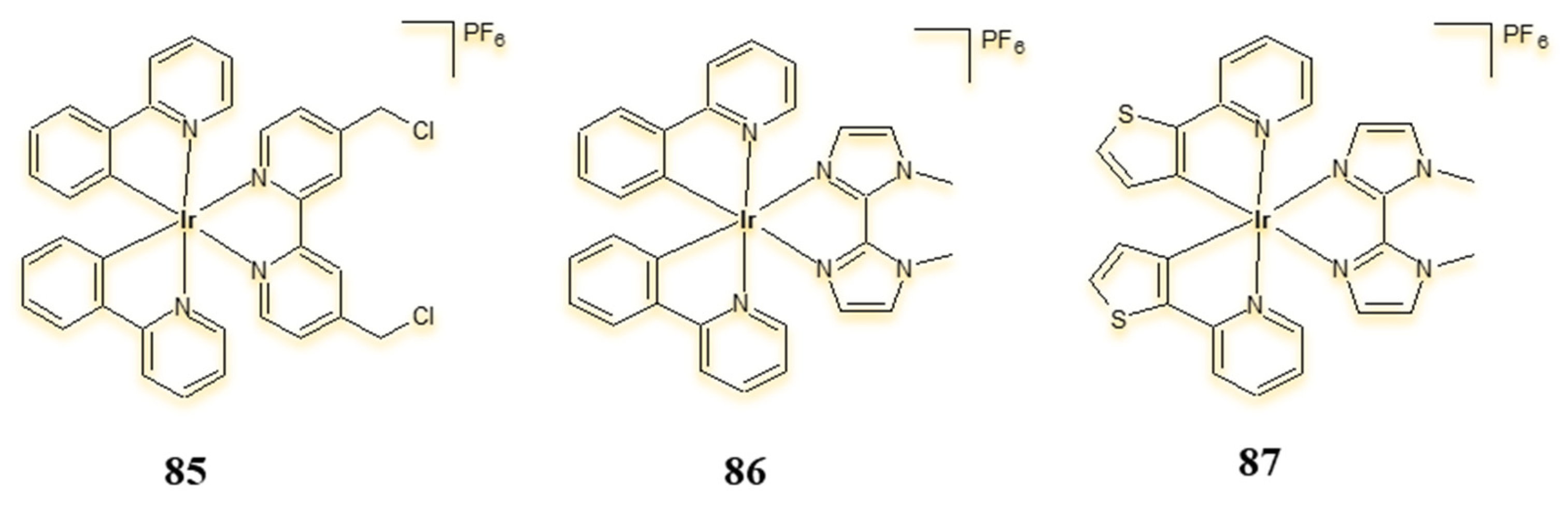

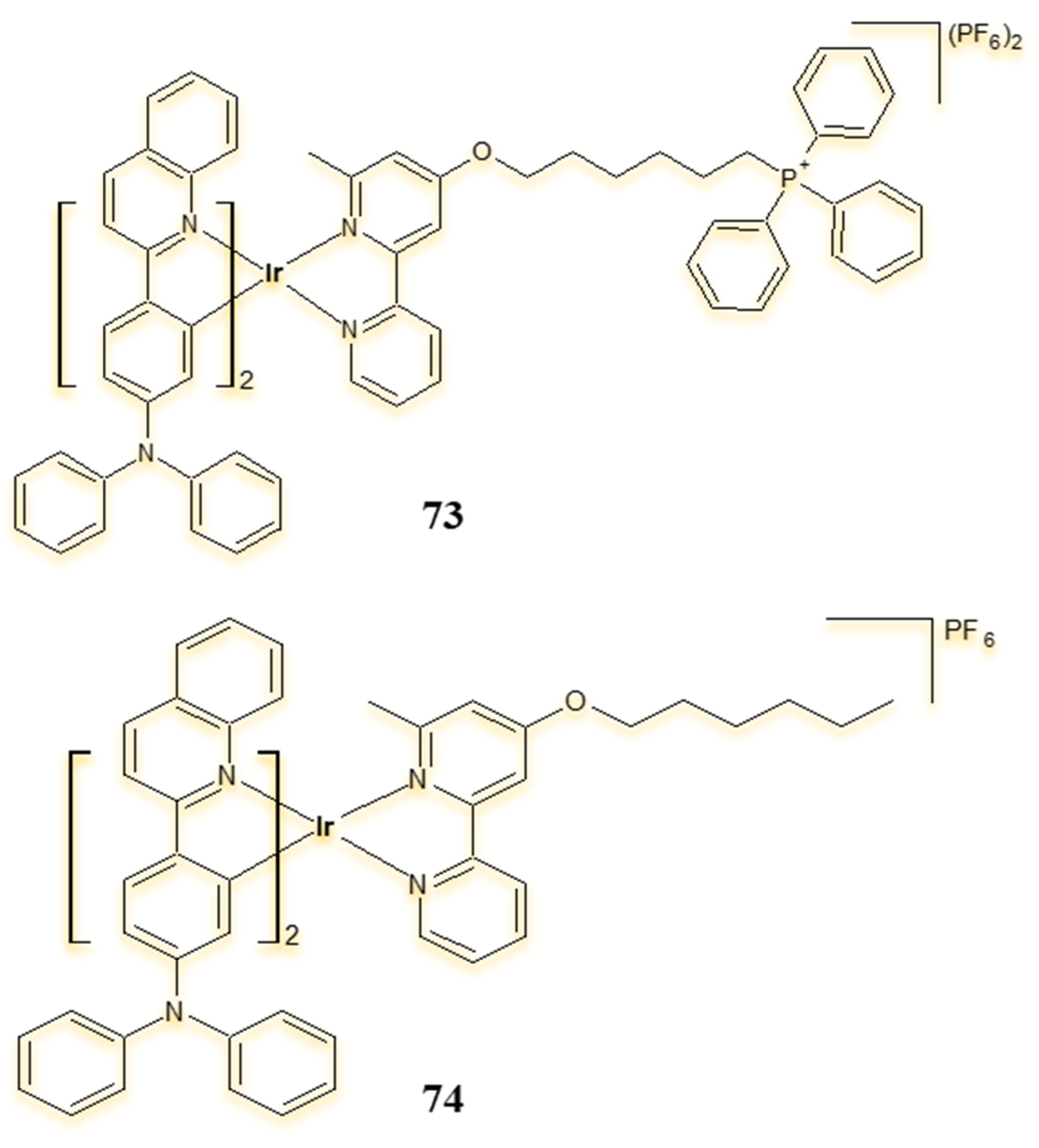

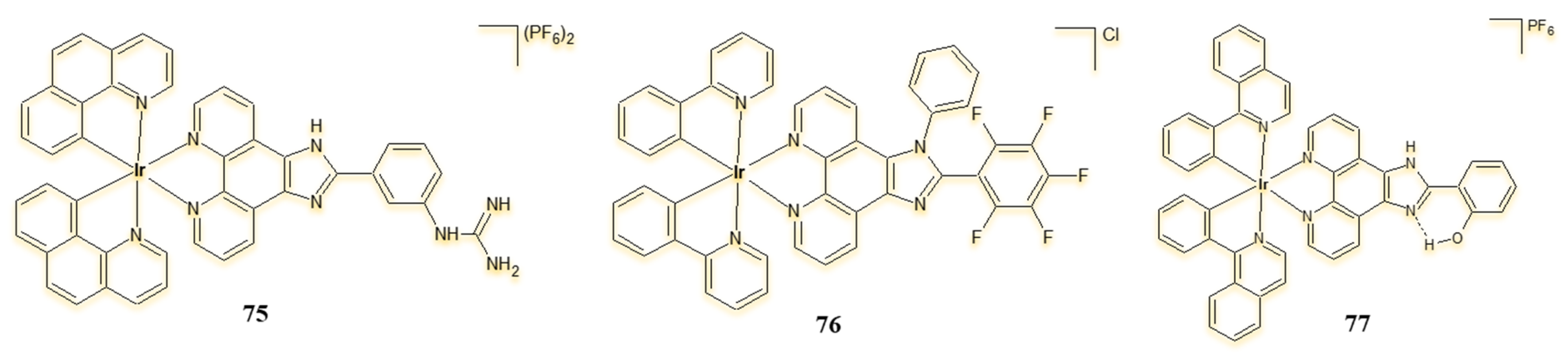

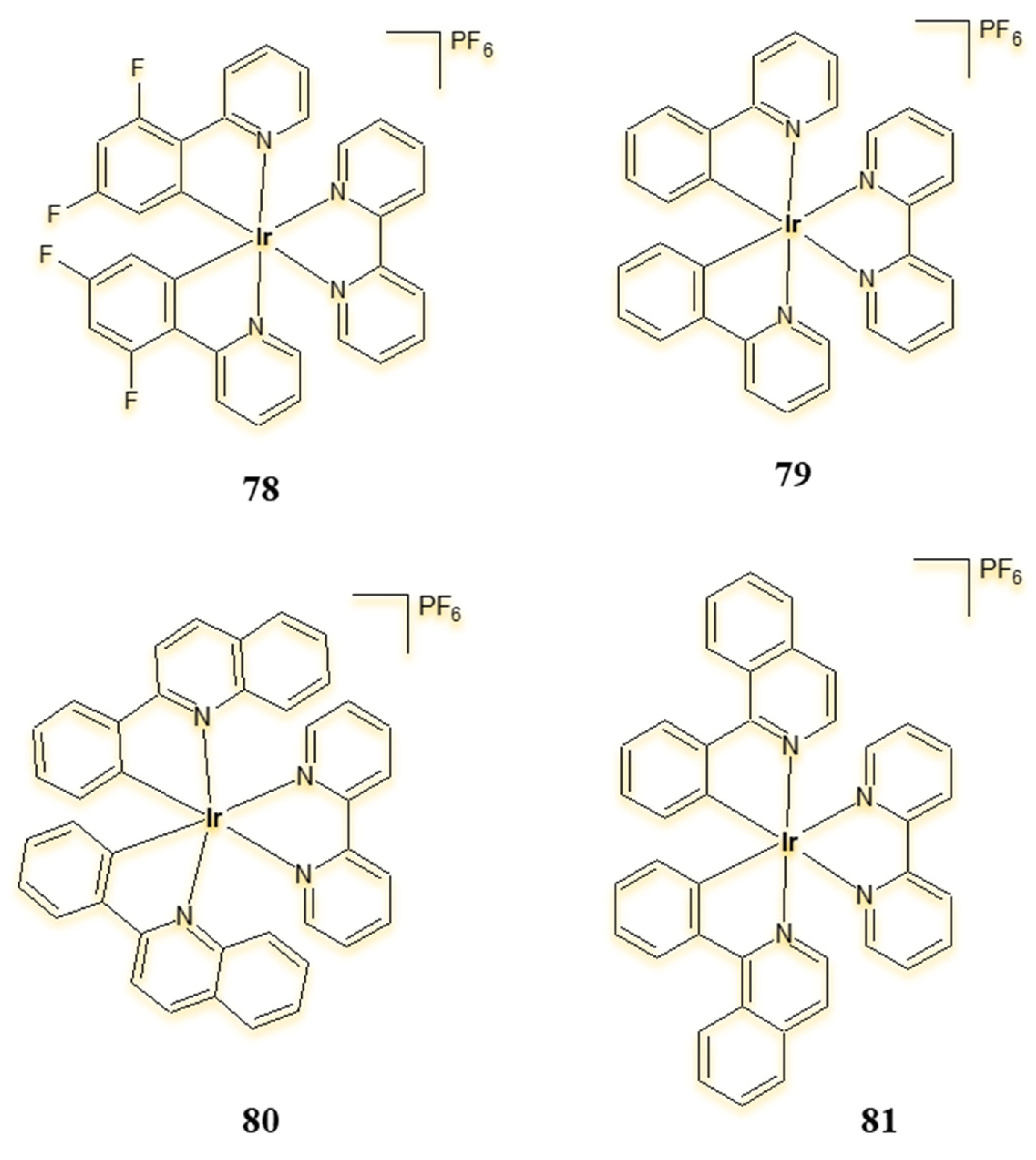

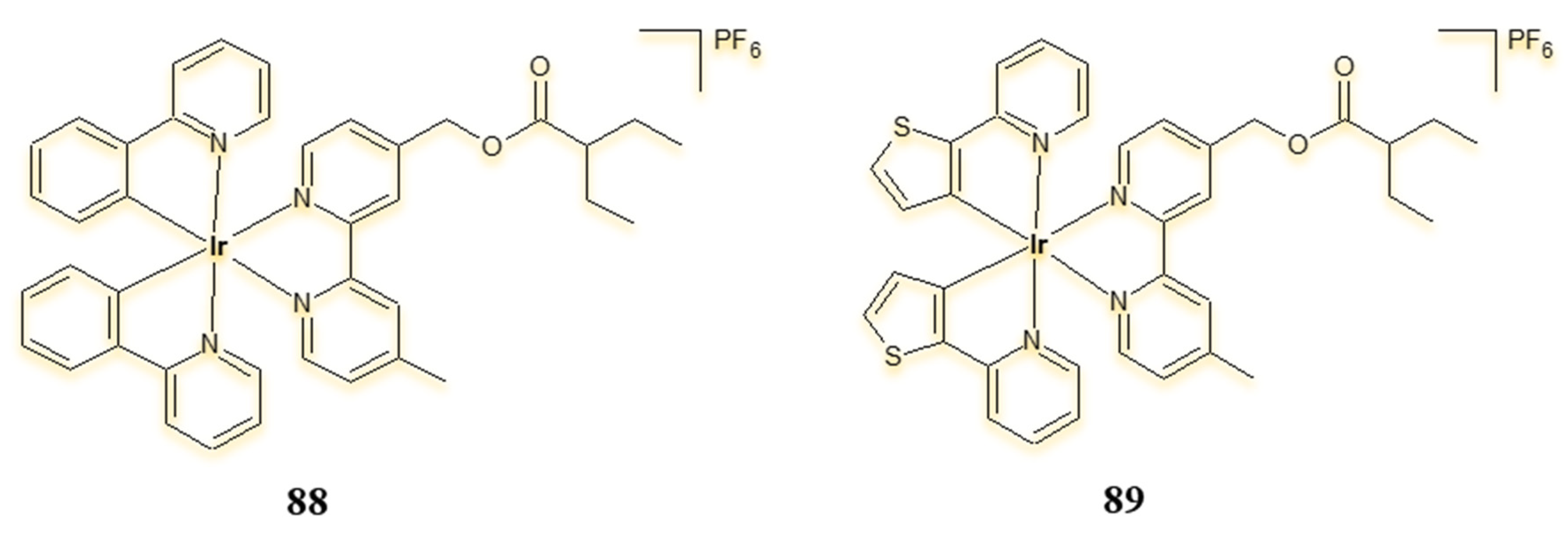

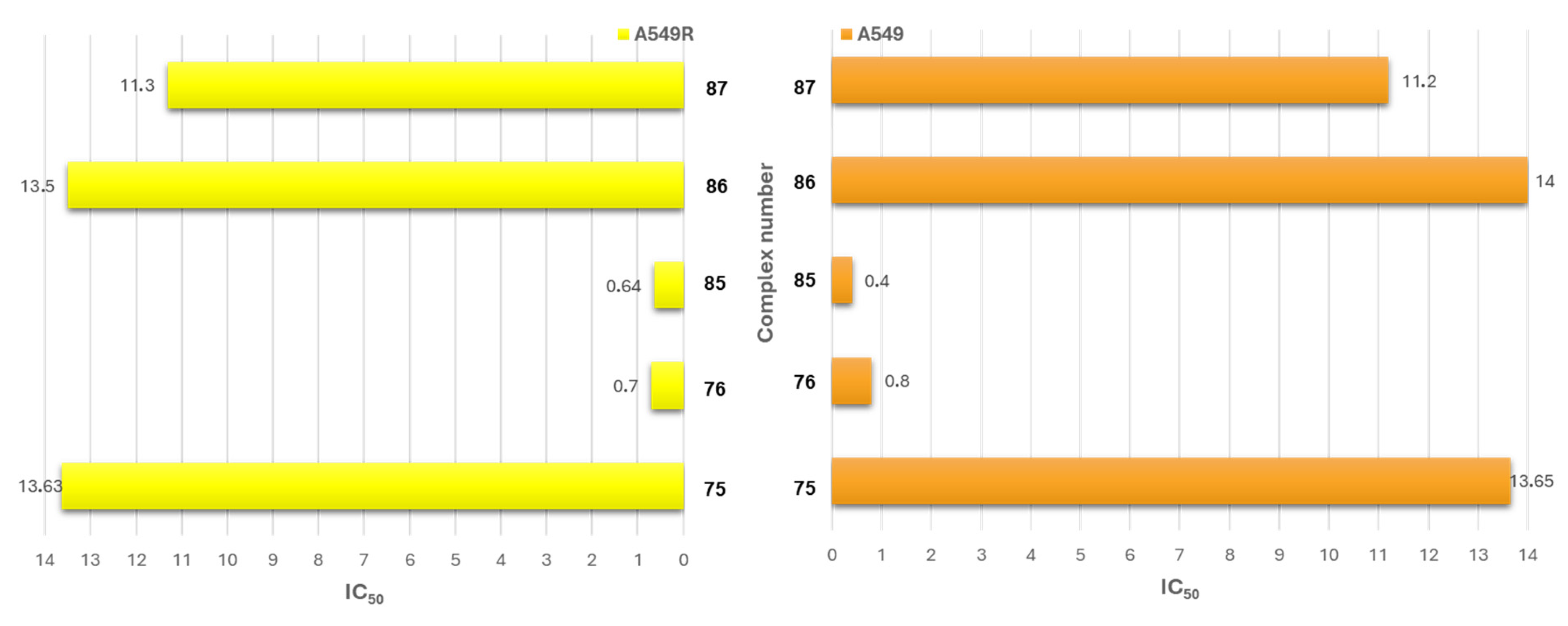

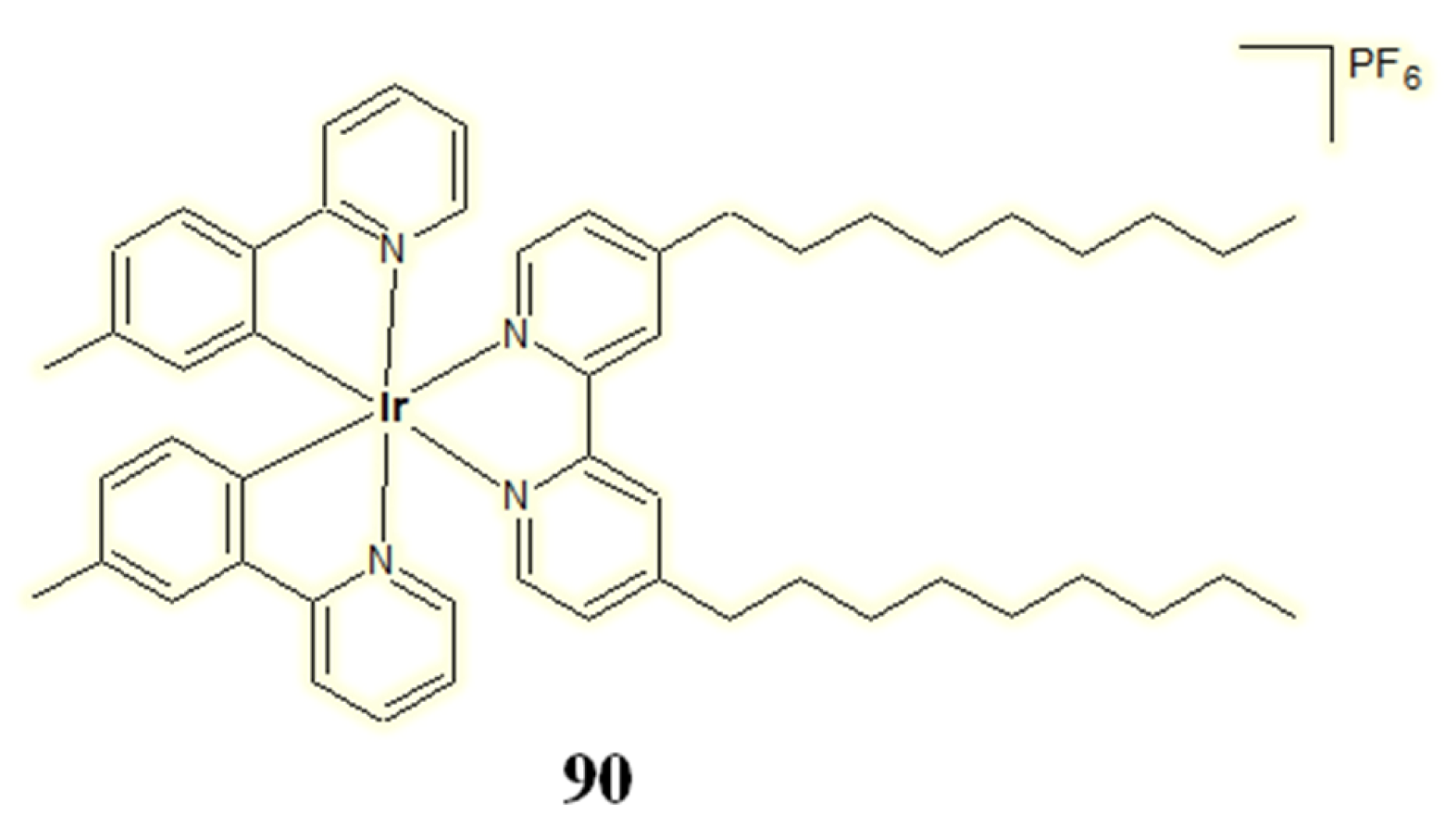

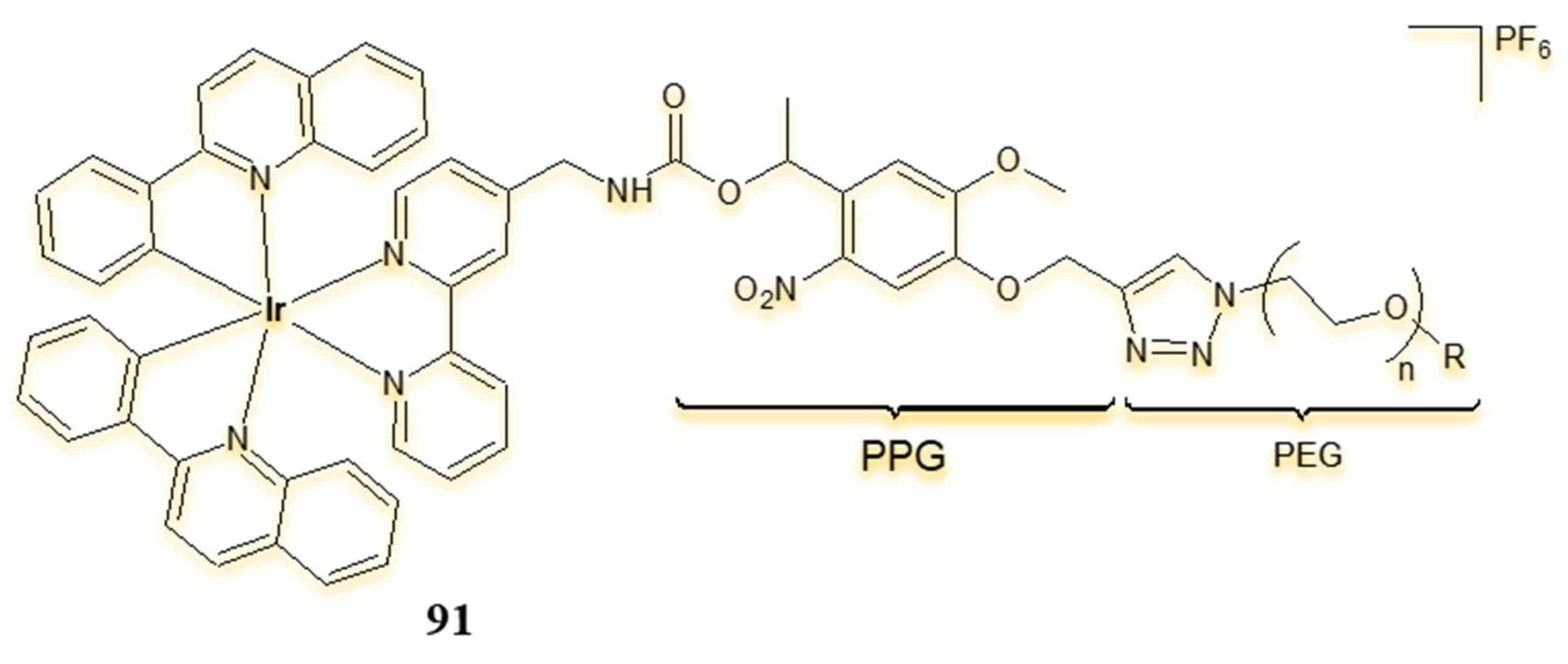

4.3. Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes as Potential Sensitisers in PDT and PACT Therapy

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ortega, E.; Vigueras, G.; Ballester, F.J.; Ruiz, J. Targeting translation: A promising strategy for anticancer metallodrugs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 446, 214129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, S.; Haribabu, J.; Balakrishnan, N.; Vasanthakumar, P.; Karvembu, R. Piano stool Ru(II)-arene complexes having three monodentate legs: A comprehensive review on their development as anticancer therapeutics over the past decade. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 459, 214403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A.; Mariconda, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Catalano, A.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Longo, P. Complexes of Ruthenium(II) as Promising Dual-Active Agents against Cancer and Viral Infections. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, L.; Macedi, E.; Giorgi, C.; Valtancoli, B.; Fusi, V. Combination of light and Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes: Recent advances in the development of new anticancer drugs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 469, 214656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simović, A.R.; Masnikosa, R.; Bratsos, I.; Alessio, E. Chemistry and reactivity of ruthenium(II) complexes: DNA/protein binding mode and anticancer activity are related to the complex structure. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 398, 113011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczynska, A.; Lewinski, A.; Pokora, M.; Paneth, P.; Budzisz, E. An Overview of the Potential Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Properties of Ru(II)/(III) Complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farwa, U.; Singh, N.; Lee, J. Self-assembly of supramolecules containing half-sandwich iridium units. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 445, 213909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLeung, H.; Zhong, H.J.; Chan, D.S.H.; Ma, D.L. Bioactive iridium and rhodium complexes as therapeutic agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 1764–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, A.; Sudhindra, P.; Roy, N.; Paira, P. Advances in novel iridium (III) based complexes for anticancer applications: A review. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2020, 513, 119925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, C.; Yu, J.; Zhu, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Photodynamic-based combinatorial cancer therapy strategies: Tuning the properties of nanoplatform according to oncotherapy needs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 461, 214495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreto, D.; Merlino, A. The interaction of rhodium compounds with proteins: A structural overview. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 442, 213999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máliková, K.; Masaryk, L.; Štarha, P. Anticancer half-sandwich rhodium(III) complexes. Inorganics 2021, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaciłowski, K.; Macyk, W.; Drzewiecka-Matuszek, A.; Brindell, M.; Stochel, G. Bioinorganic photochemistry: Frontiers and mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2647–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, R.; Francos, J.; Tomás-Mendivil, E.; Crochet, P.; Cadierno, V. Metal-catalyzed nitrile hydration reactions: The specific contribution of ruthenium. J. Organomet. Chem. 2014, 771, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, F.B.; Sun, T.; Xiao, S.; Verpoort, F. Olefin metathesis ruthenium catalysts bearing unsymmetrical heterocylic carbenes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2274–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, Z. A highly active ruthenium(II) pyrazolyl-pyridyl-pyrazole complex catalyst for transfer hydrogenation of ketones. Organometallics 2012, 31, 5664–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyrov, R.; Azap, C.; Weidlich, S.; Wolf, D. Robust and selective metathesis catalysts for oleochemical applications. Top. Catal. 2012, 55, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, C.-J. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Organic Synthesis in Aqueous Media. In Ruthenium Catalysts and Fine Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.G.; Kelly, J.M. Ruthenium polypyridyl chemistry; From basic research to applications and back again. Dalton Trans. 2006, 41, 4869–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.K.W.; Li, S.P.Y.; Zhang, K.Y. Development of luminescent iridium(iii) polypyridine complexes as chemical and biological probes. New J. Chem. 2011, 35, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbuer, A.; Vlecken, D.H.; Schmitz, D.J.; Kräling, K.; Harms, K.; Bagowski, C.P.; Meggers, E. Iridium complex with antiangiogenic properties. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3839–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Cancer Facts & Figures 4th American Cancer Society. Estimated Number of New Cancer Cases by World Area, 2018; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jemal, A.; Bray, F.; Center, M.M.; Ferlay, J.; Ward, E.; Forman, D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollin, S.; Riedel, R.; Harms, K.; Meggers, E. Octahedral rhodium(III) complexes as kinase inhibitors: Control of the relative stereochemistry with acyclic tridentate ligands. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 148, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, V.H.M.B.; Vancamp, L.; Trosko, J.E. Platinum compounds: A new class of potent antitumour agents. Nature 1969, 222, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alama, A.; Orengo, A.M.; Ferrini, S.; Gangemi, R. Targeting cancer-initiating cell drug-resistance: A Sroadmap to a new-generation of cancer therapies? Drug Discov. Today 2012, 17, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.; Bernard Tchounwou, P. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florea, A.M.; Büsselberg, D. Cisplatin as an anti-tumor drug: Cellular mechanisms of activity, drug resistance and induced side effects. Cancers 2011, 3, 1351–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheate, N.J.; Walker, S.; Craig, G.E.; Oun, R. The status of platinum anticancer drugs in the clinic and in clinical trials. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 8113–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Senovilla, L.; Vitale, I.; Michels, J.; Martins, I.; Kepp, O.; Castedo, M.; Kroemer, G. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1869–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Canelón, I.; Sadler, P.J. Next-generation metal anticancer complexes: Multitargeting via redox modulation. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 12276–12291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; Thornback, J.R. Medicinal Applications of Coordination Chemistry. Platin. Met. Rev. 2008, 52, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabas, M.; Milner, R.; Lurie, D.; Adin, C. Cisplatin: A review of toxicities and therapeutic applications. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2008, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedijk, J. Metal-ligand exchange kinetics in platinum and ruthenium complexes: Significance for effectiveness as anticancer drugs. Platin. Met. Rev. 2008, 52, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.U.; Hashmi, A.A.; Khan, S.A. Advances in Metallodrugs Preparation and Applications in Medicinal Chemistry; Wiley-Scrivener: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Allardyce, C.S.; Dyson, P.J. Ruthenium in Medicine: Current Clinical Uses and Future Prospects. Platin. Met. Rev. 2001, 45, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Emadi, A. Ruthenium-based chemotherapeutics: Are they ready for prime time? Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2010, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, B.; Shivashankar, M. Recent Advancement in the Synthesis of Ir-Based Complexes. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 43408–43432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medici, S.; Peana, M.; Nurchi, V.M.; Lachowicz, J.I.; Crisponi, G.; Zoroddu, M.A. Noble metals in medicine: Latest advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 284, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratsos, I.; Jedner, S.; Gianferrara, T.; Alessio, E. Ruthenium anticancer compounds: Challenges and expectations. Chimia 2007, 61, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunden, B.M.; Stenzel, M.H. Incorporating ruthenium into advanced drug delivery carriers—An innovative generation of chemotherapeutics. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 90, 1177–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YYan, K.; Melchart, M.; Habtemariam, A.; Sadler, P.J. Organometallic chemistry, biology and medicine: Ruthenium arene anticancer complexes. Chem. Commun. 2005, 38, 4764–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süss-Fink, G. Arene ruthenium complexes as anticancer agents. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 1673–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamo, A.; Sava, G. Ruthenium complexes can target determinants of tumour malignancy. Dalton Trans. 2007, 13, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabec, V.; Kasparkova, J. Ruthenium coordination compounds of biological and biomedical significance. DNA binding agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 376, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, I.; Bashir, M.; Arjmand, F.; Tabassum, S. Advancement of metal compounds as therapeutic and diagnostic metallodrugs: Current frontiers and future perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 445, 214104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.K.; Strehle, A.P.; Miller, R.L.; Gammons, S.H.; Hoffman, K.J.; McCarty, J.T.; Miller, M.E.; Stultz, L.K.; Hanson, P.K. The anticancer ruthenium complex KP1019 induces DNA damage, leading to cell cycle delay and cell death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 83, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allardyce, C.S.; Dorcier, A.; Scolaro, C.; Dyson, P.J. Development of organometallic (organo-transition metal) pharmaceuticals. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, E.; Mestroni, G.; Bergamo, A.; Sava, G. Ruthenium Antimetastatic Agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2004, 4, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijen, S.; Burgers, S.A.; Baas, P.; Pluim, D.; Tibben, M.; Van Werkhoven, E.; Alessio, E.; Sava, G.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H.M. Phase I/II study with ruthenium compound NAMI-A and gemcitabine in patients with non-small cell lung cancer after first line therapy. Investig. New Drugs 2015, 33, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, E. Thirty Years of the Drug Candidate NAMI-A and the Myths in the Field of Ruthenium Anticancer Compounds: A Personal Perspective. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 2017, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messori, L.; Orioli, P.; Vullo, D.; Alessio, E.; Iengo, E. A spectroscopic study of the reaction of NAMI, a novel ruthenium(III) anti-neoplastic complex, with bovine serum albumin. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillozzi, S.; Gasparoli, L.; Stefanini, M.; Ristori, M.; D’Amico, M.; Alessio, E.; Scaletti, F.; Becchetti, A.; Arcangeli, A.; Messori, L. NAMI-A is highly cytotoxic toward leukaemia cell lines: Evidence of inhibition of KCa 3.1 channels. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 12150–12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, E.; Messori, L. NAMI-A and KP1019/1339, two iconic ruthenium anticancer drug candidates face-to-face: A case story in medicinal inorganic chemistry. Molecules 2019, 24, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker-Lakhai, J.M.; Van Den Bongard, D.; Pluim, D.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H.M. A Phase I and pharmacological study with imidazolium-trans-DMSO-imidazole-tetrachlororuthenate, a novel ruthenium anticancer agent. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 3717–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernitznig, D.; Kiakos, K.; Del Favero, G.; Harrer, N.; MacHat, H.; Osswald, A.; Jakupec, M.A.; Wernitznig, A.; Sommergruber, W.; Keppler, B.K. First-in-class ruthenium anticancer drug (KP1339/IT-139) induces an immunogenic cell death signature in colorectal spheroids: In vitro. Metallomics 2019, 11, 1044–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trynda-Lemiesz, L.; Keppler, B.K.; Koztowski, H. Studies on the interactions between human serum albumin and imidazolium [trans-tetrachlorobis (imidazol) ruthenate (III)]. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999, 73, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartinger, C.G.; Jakupec, M.A.; Zorbas-Seifried, S.; Groessl, M.; Egger, A.; Berger, W.; Zorbas, H.; Dyson, P.J.; Keppler, B.K. KP1019, A New Redox-Active Anticancer Agent-Preclinical Development and Results of a Clinical Phase I Study in Tumor Patients. Chemestry Biodivers. 2008, 5, 2140–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trondl, R.; Heffeter, P.; Kowol, C.R.; Jakupec, M.A.; Berger, W.; Keppler, B.K. NKP-1339, the first ruthenium-based anticancer drug on the edge to clinical application. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 2925–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groessl, M.; Tsybin, Y.O.; Hartinger, C.G.; Keppler, B.K.; Dyson, P.J. Ruthenium versus platinum: Interactions of anticancer metallodrugs with duplex oligonucleotides characterised by electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 15, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytzek, A.K.; Koellensperger, G.; Keppler, B.K.; Hartinger, C.G. Biodistribution of the novel anticancer drug sodium trans-[tetrachloridobis(1H-indazole)ruthenate(III)] KP-1339/IT139 in nude BALB/c mice and implications on its mode of action. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 160, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.I.; Walsby, C.J. Control of ligand-exchange processes and the oxidation state of the antimetastatic Ru(iii) complex NAMI-A by interactions with human serum albumin. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungwirth, U.; Kowol, C.R.; Keppler, B.K.; Hartinger, C.G.; Berger, W.; Heffeter, P. Anticancer activity of metal complexes: Involvement of redox processes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1085–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, B. The components of the wired spanning forest are recurrent. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 2003, 125, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LStultz, K.; Hunsucker, A.; Middleton, S.; Grovenstein, E.; O’Leary, J.; Blatt, E.; Miller, M.; Mobley, J.; Hanson, P.K. Proteomic analysis of the S. cerevisiae response to the anticancer ruthenium complex KP1019. Metallomics 2020, 12, 876–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, J.B.; Antony, S.; Weekley, C.M.; Lai, B.; Spiccia, L.; Harris, H.H. Distinct cellular fates for KP1019 and NAMI-A determined by X-ray fluorescence imaging of single cells. Metallomics 2012, 4, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostetter, A.A.; Miranda, M.L.; Derose, V.J.; Holman, K.L.M. Ru binding to RNA following treatment with the antimetastatic prodrug NAMI-A in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in vitro. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 16, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depeursinge, A.; Racoceanu, D.; Iavindrasana, J.; Cohen, G.; Platon, A.; Poletti, P.A.; Müller, H. Fusing visual and clinical information for lung tissue classification in high-resolution computed tomography. Artif. Intell. Med. 2010, 50, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monro, S.; Colón, K.L.; Yin, H.; Roque, J.; Konda, P.; Gujar, S.; Thummel, R.P.; Lilge, L.; Cameron, C.G.; McFarland, S.A. Transition Metal Complexes and Photodynamic Therapy from a Tumor-Centered Approach: Challenges, Opportunities, and Highlights from the Development of TLD1433. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 797–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Monro, S.; Hennigar, R.; Colpitts, J.; Fong, J.; Kasimova, K.; Yin, H.; DeCoste, R.; Spencer, C.; Chamberlain, L.; et al. Ru(II) dyads derived from α-oligothiophenes: A new class of potent and versatile photosensitizers for PDT. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 282–283, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainuddin, T.; McCain, J.; Pinto, M.; Yin, H.; Gibson, J.; Hetu, M.; McFarland, S.A. Organometallic Ru(II) Photosensitizers Derived from π-Expansive Cyclometalating Ligands: Surprising Theranostic PDT Effects. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, S.A.; Mandel, A.; Dumoulin-White, R.; Gasser, G. Metal-based photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy: The future of multimodal oncology? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 56, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithen, D.A.; Monro, S.; Pinto, M.; Roque, J.; Diaz-Rodriguez, R.M.; Yin, H.; Cameron, C.G.; Thompson, A.; Mcfarland, S.A. Bis[pyrrolyl Ru(ii)] triads: A new class of photosensitizers for metal-organic photodynamic therapy. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12047–12069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, J.; Havrylyuk, D.; Barrett, P.C.; Sainuddin, T.; McCain, J.; Colón, K.; Sparks, W.T.; Bradner, E.; Monro, S.; Heidary, D.; et al. Strained, Photoejecting Ru(II) Complexes that are Cytotoxic Under Hypoxic Conditions. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.T.; Pina, J.; Ribeiro, C.A.F.; Fernandes, R.; Tomé, J.P.C.; Rodríguez-Morgade, M.S.; Torres, T. PEG-containing ruthenium phthalocyanines as photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy: Synthesis, characterization and in vitro evaluation. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 5862–5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascheroni, L.; Dozzi, M.V.; Ranucci, E.; Ferruti, P.; Francia, V.; Salvati, A.; Maggioni, D. Tuning Polyamidoamine Design to Increase Uptake and Efficacy of Ruthenium Complexes for Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 14586–14599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Colombo, E.; Vinck, R.; Mari, C.; Rubbiani, R.; Patra, M.; Gasser, G. Increased Lipophilicity of Halogenated Ruthenium(II) Polypyridyl Complexes Leads to Decreased Phototoxicity in vitro when Used as Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 2966–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithen, D.A.; Yin, H.; Beh, M.H.R.; Hetu, M.; Cameron, T.S.; McFarland, S.A.; Thompson, A. Synthesis and Photobiological Activity of Ru(II) Dyads Derived from Pyrrole-2-carboxylate Thionoesters. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 4121–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.T.; Stevens, K.C.; Calabro, R.; Parkin, S.; Mahmoud, J.; Kim, D.Y.; Heidary, D.K.; Glazer, E.C.; Selegue, J.P. Bis-tridentate N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ru(II) Complexes are Promising New Agents for Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 8882–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.M.; Zhu, C.F.; Lu, Y.N.; Wu, J.Z.; Li, J.; Liu, H.Y.; Ye, Y. Photodynamic antitumor activity of Ru(ii) complexes of imidazo-phenanthroline conjugated hydroxybenzoic acid as tumor targeting photosensitizers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Kundu, P.; Bhattacharyya, U.; Garai, A.; Maji, R.C.; Kondaiah, P.; Chakravarty, A.R. Ruthenium(II) Conjugates of Boron-Dipyrromethene and Biotin for Targeted Photodynamic Therapy in Red Light. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Qiu, K.; Liu, J.; Hao, X.; Wang, J. Two-photon photodynamic ablation of tumour cells using an RGD peptide-conjugated ruthenium(ii) photosensitiser. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 12542–12545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, E.; Hu, X.; Roy, S.; Wang, P.; Deasy, K.; Mochizuki, T.; Zhang, Y. Taurine-modified Ru(II)-complex targets cancerous brain cells for photodynamic therapy. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 6033–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, V.; Aute, S.; Taye, N.; Guha, R.; Walker, M.G.; Mogare, D.; Parulekar, A.; Thomas, J.A.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Das, A. Photo-induced cytotoxicity and anti-metastatic activity of ruthenium(II)-polypyridyl complexes functionalized with tyrosine or tryptophan. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 6634–6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.J.; Negri, L.B.; Pernomian, L.; Faial, K.D.C.F.; Xue, C.; Akhimie, R.N.; Hamblin, M.R.; Turro, C.; da Silva, R.S. The Influence of Some Axial Ligands on Ruthenium–Phthalocyanine Complexes: Chemical, Photochemical, and Photobiological Properties. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 7, 595830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, S.A.; Raza, A.; Dröge, F.; Robertson, C.; Auty, A.J.; Chekulaev, D.; Weinstein, J.A.; Keane, T.; Meijer, A.J.H.M.; Haycock, J.W.; et al. A dinuclear ruthenium(ii) phototherapeutic that targets duplex and quadruplex DNA. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 3502–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havrylyuk, D.; Heidary, D.K.; Nease, L.; Parkin, S.; Glazer, E.C. Photochemical Properties and Structure–Activity Relationships of RuII Complexes with Pyridylbenzazole Ligands as Promising Anticancer Agents. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 2017, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, L.; Nease, L.; Vo, P.; Garofolo, J.; Heidary, D.K.; Thummel, R.P.; Glazer, E.C. Photochemical and Photobiological Activity of Ru(II) Homoleptic and Heteroleptic Complexes Containing Methylated Bipyridyl-type Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 12214–12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, F.J.; Ortega, E.; Bautista, D.; Santana, M.D.; Ruiz, J. Ru(ii) photosensitizers competent for hypoxic cancersviagreen light activation. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 10301–10304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, A.; Vigueras, G.; Rodríguez, V.; Santana, M.D.; Ruiz, J. Cyclometalated iridium(III) luminescent complexes in therapy and phototherapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 360, 34–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, A.; Denning, C.A.; Heidary, D.K.; Wachter, E.; Nease, L.A.; Ruiz, J.; Glazer, E.C. Ruthenium-containing P450 inhibitors for dual enzyme inhibition and DNA damage. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 2165–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, L.K. Medical Therapy of Cushing’s Disease; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, P.H.; Telfer, C.; Mcfadyen, M.C.E.; Melvin, W.T.; Murray, G.I. The Role of Cytochrome P450 in Cytotoxic Bioactivation: Future Therapeutic Directions. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2004, 4, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.D.; Njar, V.C.O. Targeting cytochrome P450 enzymes: A new approach in anti-cancer drug development. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 5047–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.; Price, A. The Effect of Cytochrome P450 Metabolism on Drug Response, Interactions, and Adverse Effects. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 76, 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Pandey, D.S.; Xu, Q.; Braunstein, P. Recent advances in supramolecular and biological aspects of arene ruthenium(II) complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 270–271, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Habtemariam, A.; Van Der Geer, E.P.L.; Ndez, R.F.; Melchart, M.; Deeth, R.J.; Aird, R.; Guichard, S.; Fabbiani, F.P.A.; Lozano-Casal, P.; et al. Controlling ligand substitution reactions of organometallic complexes: Tuning cancer cell cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18269–18274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renfrew, A.K.; Scopelliti, R.; Dyson, P.J. Use of perfluorinated phosphines to provide thermomorphic anticancer complexes for heat-based tumor targeting. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, A.; Melchart, M.; Fernández, R.; Parsons, S.; Oswald, I.D.H.; Parkin, A.; Fabbiani, F.P.A.; Davidson, J.E.; Dawson, A.; Aird, R.E.; et al. Structure-activity relationships for cytotoxic ruthenium(II) arene complexes containing N,N-, N,O-, and O,O-chelating ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6858–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremlett, W.D.J.; Goodman, D.M.; Steel, T.R.; Kumar, S.; Wieczorek-Błauż, A.; Walsh, F.P.; Sullivan, M.P.; Hanif, M.; Hartinger, C.G. Design concepts of half-sandwich organoruthenium anticancer agents based on bidentate bioactive ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 445, 213950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughrey, B.T.; Williams, M.L.; Healy, P.C.; Innocenti, A.; Vullo, D.; Supuran, C.T.; Parsons, P.G.; Poulsen, S.A. Novel organometallic cationic ruthenium(II) pentamethylcyclopentadienyl benzenesulfonamide complexes targeted to inhibit carbonic anhydrase. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 14, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.J.; Wang, J.Q.; Kou, J.F.; Li, G.Y.; Wang, L.L.; Chao, H.; Ji, L.N. Synthesis, DNA-binding and topoisomerase inhibitory activity of ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, V.; Kondapi, A.K. Topoisomerase II poisoning by indazole and imidazole complexes of ruthenium. J. Biosci. 2001, 26, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Chao, H.; Wang, J.Q.; Yuan, Y.X.; Sun, B.; Wei, Y.F.; Peng, B.; Ji, L.N. Targeting topoisomerase II with the chiral DNA-intercalating ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 12, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, M.; Schluga, P.; Jakupec, M.A.; Arion, V.B.; Hartinger, C.G.; Allmaier, G.; Keppler, B.K. Transferrin binding and transferrin-mediated cellular uptake of the ruthenium coordination compound KP1019, studied by means of AAS, ESI-MS and CD spectroscopy. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2004, 19, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, H.; Parsons, S.; Oswald, I.D.H.; Davidson, J.E.; Sadler, P.J. Kinetics of Aquation and Anation of Ruthenium(II) Arene Anticancer Complexes, Acidity and X-ray Structures of Aqua Adducts. Chem.-Eur. J. 2003, 9, 5810–5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levina, A.; Lay, P.A. Influence of an anti-metastatic ruthenium(iii) prodrug on extracellular protein-protein interactions: Studies by bio-layer interferometry. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2014, 1, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, P.J. Systematic design of a targeted organometallic antitumour drug in pre-clinical development. Chimia 2007, 61, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougan, S.J.; Sadler, P.J. The design of organometallic ruthenium arene anticancer agents. Chimia 2007, 61, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, H.A.; Dyson, P.J. Classical and non-classical ruthenium-based anticancer drugs: Towards targeted chemotherapy. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 2006, 4003–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, S.; Rodrigues, D.A.; Crans, D.C.; Barreiro, E.J. Ru(II) Compounds: Next-Generation Anticancer Metallotherapeutics? J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5805–5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, M.; Dyson, P.J.; Nowak-Sliwinska, P. Recent Considerations in the Application of RAPTA-C for Cancer Treatment and Perspectives for Its Combination with Immunotherapies. Adv. Ther. 2019, 2, 1900042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, A.A.; Hartinger, C.G.; Dyson, P.J. Opening the lid on piano-stool complexes: An account of ruthenium(II)earene complexes with medicinal applications. J. Organomet. Chem. 2014, 751, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coverdale, J.P.C.; Laroiya-McCarron, T.; Romero-Canelón, I. Designing ruthenium anticancer drugs: What have we learnt from the key drug candidates? Inorganics 2019, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Bo, H.B.; Hao, X.J.; Wang, J.Q. Applications of ruthenium complex in tumor diagnosis and therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhireksan, Z.; Davey, G.E.; Campomanes, P.; Groessl, M.; Clavel, C.M.; Yu, H.; Nazarov, A.A.; Yeo, C.H.F.; Ang, W.H.; Dröge, P.; et al. Ligand substitutions between ruthenium-cymene compounds can control protein versus DNA targeting and anticancer activity. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, G.; Magistrato, A.; Riedel, T.; von Erlach, T.; Davey, C.A.; Dyson, P.J.; Rothlisberger, U. Fighting Cancer with Transition Metal Complexes: From Naked DNA to Protein and Chromatin Targeting Strategies. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, A.; Berndsen, R.H.; Dubois, M.; Müller, C.; Schibli, R.; Griffioen, A.W.; Dyson, P.J.; Nowak-Sliwinska, P. In vivo anti-tumor activity of the organometallic ruthenium(ii)-arene complex [Ru(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(pta)] (RAPTA-C) in human ovarian and colorectal carcinomas. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4742–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, S.; Haribabu, J.; Kalagatur, N.K.; Konakanchi, R.; Balakrishnan, N.; Bhuvanesh, N.; Karvembu, R. Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of [RuCl 2 (n 6 -arene)(aroylthiourea)] Complexes—High Activity against the Human Neuroblastoma (IMR-32) Cancer Cell Line. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 6245–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golbaghi, G.; Haghdoost, M.M.; Yancu, D.; De Los Santos, Y.L.; Doucet, N.; Patten, S.A.; Sanderson, J.T.; Castonguay, A. Organoruthenium(II) Complexes Bearing an Aromatase Inhibitor: Synthesis, Characterization, in Vitro Biological Activity and in Vivo Toxicity in Zebrafish Embryos. Organometallics 2019, 38, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasi, E.; Atalay, E.B.; Erdogan, D.; Sen, B.; Pakyapan, B.; Kayali, H.A. Synthesis and characterization of thiosemicarbazone-functionalized organoruthenium (II)-arene complexes: Investigation of antitumor characteristics in colorectal cancer cell lines. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 106, 110152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, B.N.; Luna-Dulcey, L.; Plutin, A.M.; Silveira, R.G.; Honorato, J.; Cairo, R.R.; De Oliveira, T.D.; Cominetti, M.R.; Castellano, E.E.; Batista, A.A. Selective Coordination Mode of Acylthiourea Ligands in Half-Sandwich Ru(II) Complexes and Their Cytotoxic Evaluation. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 5072–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castonguay, A.; Doucet, C.; Juhas, M.; Maysinger, D. New ruthenium(II)-letrozole complexes as anticancer therapeutics. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 8799–8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colina-Vegas, L.; Godinho, J.L.P.; Coutinho, T.; Correa, R.S.; De Souza, W.; Rodrigues, J.C.F.; Batista, A.A.; Navarro, M. Antiparasitic activity and ultrastructural alterations provoked by organoruthenium complexes against: Leishmania amazonensis. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 1431–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszaukowski, F.; Guimarães, I.D.L.; da Silva, J.P.; da Silveira Lacerda, L.H.; de Lazaro, S.R.; de Araujo, M.P.; Castellen, P.; Tominaga, T.T.; Boeré, R.T.; Wohnrath, K. Ruthenium(II)-arene complexes with monodentate aminopyridine ligands: Insights into redox stability and electronic structures and biological activity. J. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 881, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elie, B.T.; Pechenyy, Y.; Uddin, F.; Contel, M. A heterometallic ruthenium–gold complex displays antiproliferative, antimigratory, and antiangiogenic properties and inhibits metastasis and angiogenesis-associated proteases in renal cancer. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 23, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołoczek, P.; Skórska-Stania, A.; Cierniak, A.; Sebastian, V.; Komarnicka, U.K.; Płotek, M.; Kyzioł, A. Polymeric micelle-mediated delivery of half-sandwich ruthenium(II) complexes with phosphanes derived from fluoroloquinolones for lung adenocarcinoma treatment. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 128, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernar, M.; Kokan, Z.; Kralj, J.; Glasovac, Z.; Tumir, L.M.; Piantanida, I.; Eljuga, D.; Turel, I.; Brozovic, A.; Kirin, S.I. Organometallic ruthenium(II)-arene complexes with triphenylphosphine amino acid bioconjugates: Synthesis, characterization and biological properties. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 87, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancalana, L.; Zacchini, S.; Ferri, N.; Lupo, M.G.; Pampaloni, G.; Marchetti, F. Tuning the cytotoxicity of ruthenium(ii) para-cymene complexes by mono-substitution at a triphenylphosphine/phenoxydiphenylphosphine ligand. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 16589–16604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, G.E.; Adhireksan, Z.; Ma, Z.; Riedel, T.; Sharma, D.; Padavattan, S.; Rhodes, D.; Ludwig, A.; Sandin, S.; Murray, B.S.; et al. Nucleosome acidic patch-targeting binuclear ruthenium compounds induce aberrant chromatin condensation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpin, K.J.; Clavel, C.M.; Edafe, F.; Dyson, P.J. Naphthalimide-tagged ruthenium-arene anticancer complexes: Combining coordination with intercalation. Organometallics 2012, 31, 7031–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, P.K.; Şen, B.; Karagöz, C.S.; Subaşı, E. Half-sandwich ruthenium-arene complexes with thiophen containing thiosemicarbazones: Synthesis and structural characterization. J. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 832, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, D.; Nikolić, S.; Milenković, I.; Milenković, M.; Jovanović, P.; Savić, V.; Roller, A.; Crnogorac, M.Đ.; Stanojković, T.; Grgurić-Šipka, S. Synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of novel half-sandwich Ru(II) arene complexes with benzoylthiourea derivatives. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 210, 111164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.; Nawaz, M.A.H.; Babak, M.V.; Iqbal, J.; Roller, A.; Keppler, B.K.; Hartinger, C.G. RutheniumII(η6-arene) complexes of thiourea derivatives: Synthesis, characterization and urease inhibition. Molecules 2014, 19, 8080–8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapasam, A.; Hussain, O.; Phillips, R.M.; Kaminsky, W.; Kollipara, M.R. Synthesis, characterization and chemosensitivity studies of half-sandwich ruthenium, rhodium and iridium complexes containing k1(S) and k2(N,S) aroylthiourea ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 880, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbaghi, G.; Pitard, I.; Lucas, M.; Haghdoost, M.M.; de los Santos, Y.L.; Doucet, N.; Patten, S.A.; Sanderson, J.T.; Castonguay, A. Synthesis and biological assessment of a ruthenium(II) cyclopentadienyl complex in breast cancer cells and on the development of zebrafish embryos. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 188, 112030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colina-Vegas, L.; Oliveira, K.M.; Cunha, B.N.; Cominetti, M.R.; Navarro, M.; Batista, A.A. Anti-proliferative and anti-migration activity of arene-ruthenium(II) complexes with azole therapeutic agents. Inorganics 2018, 6, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastuszko, A.; Niewinna, K.; Czyz, M.; Jóźwiak, A.; Małecka, M.; Budzisz, E. Synthesis, X-ray structure, electrochemical properties and cytotoxic effects of new arene ruthenium(II) complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 745–746, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Singh, S.; Draca, D.; Kate, A.; Kumbhar, A.; Kumbhar, A.S.; Maksimovic-Ivanic, D.; Mijatovic, S.; Lönnecke, P.; Hey-Hawkins, E. Antiproliferative activity of ruthenium(II) arene complexes with mono- and bidentate pyridine-based ligands. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 13114–13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renfrew, A.K.; Karges, J.; Scopelliti, R.; Bobbink, F.D.; Nowak-Sliwinska, P.; Gasser, G.; Dyson, P.J. Towards Light-Activated Ruthenium–Arene (RAPTA-Type) Prodrug Candidates. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 2876–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, J.; Noe, V.; Ciudad, C.; Prieto, M.J.; Font-Bardia, M.; Calvet, T.; Moreno, V. New π-arene ruthenium(II) piano-stool complexes with nitrogen ligands. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 109, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanic-Vucinic, D.; Nikolic, S.; Vlajic, K.; Radomirovic, M.; Mihailovic, J.; Velickovic, T.C.; Grguric-Sipka, S. The interactions of the ruthenium(II)-cymene complexes with lysozyme and cytochrome c. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 25, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babak, M.V.; Meier, S.M.; Legin, A.A.; Razavi, M.S.A.; Roller, A.; Jakupec, M.A.; Keppler, B.K.; Hartinger, C.G. Am(m)ines make the difference: Organoruthenium Am(m)ine complexes and their chemistry in anticancer drug development. Chem.-Eur. J. 2013, 19, 4308–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgurić-Šipka, S.; Ivanović, I.; Rakić, G.; Todorović, N.; Gligorijević, N.; Radulović, S.; Arion, V.B.; Keppler, B.K.; Tešić, Ž.L. Ruthenium(II)-arene complexes with functionalized pyridines: Synthesis, characterization and cytotoxic activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gallardo, J.; Elie, B.T.; Sanaú, M.; Contel, M. Versatile synthesis of cationic N-heterocyclic carbene-gold(I) complexes containing a second ancillary ligand. Design of heterobimetallic ruthenium-gold anticancer agents. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3155–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betanzos-Lara, S.; Habtemariam, A.; Clarkson, G.J.; Sadler, P.J. Organometallic cis-dichlorido ruthenium(II) ammine complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 3257–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broomfield, L.M.; Alonso-Moreno, C.; Martin, E.; Shafir, A.; Posadas, I.; Ceña, V.; Castro-Osma, J.A. Aminophosphine ligands as a privileged platform for development of antitumoral ruthenium(II) arene complexes. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 16113–16125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotek, M.; Starosta, R.; Komarnicka, U.K.; Skórska-Stania, A.; Kołoczek, P.; Kyzioł, A. Ruthenium(II) piano stool coordination compounds with aminomethylphosphanes: Synthesis, characterisation and preliminary biological study in vitro. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 170, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancalana, L.; Batchelor, L.K.; De Palo, A.; Zacchini, S.; Pampaloni, G.; Dyson, P.J.; Marchetti, F. A general strategy to add diversity to ruthenium arene complexes with bioactive organic compounds: Via a coordinated (4-hydroxyphenyl)diphenylphosphine ligand. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 12001–12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, G.; Kaluderović, G.N.; Bette, M.; Block, M.; Paschke, R.; Steinborn, D. Highly active neutral ruthenium(II) arene complexes: Synthesis, characterization, and investigation of their anticancer properties. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 113, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, M.A.; Schmitt, F.; Wiederkehr, M.; Juillerat-Jeanneret, L.; Therrien, B. Cellular delivery of pyrenyl-arene ruthenium complexes by a water-soluble arene ruthenium metalla-cage. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 7201–7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.S.; Menin, L.; Scopelliti, R.; Dyson, P.J. Conformational control of anticancer activity: The application of arene-linked dinuclear ruthenium(ii) organometallics. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 2536–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpin, K.J.; Cammack, S.M.; Clavel, C.M.; Dyson, P.J. Ruthenium(ii) arene PTA (RAPTA) complexes: Impact of enantiomerically pure chiral ligands. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 2008–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, A.A.; Meier, S.M.; Zava, O.; Nosova, Y.N.; Milaeva, E.R.; Hartinger, C.G.; Dyson, P.J. Protein ruthenation and DNA alkylation: Chlorambucil-functionalized RAPTA complexes and their anticancer activity. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 3614–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, W.H.; Parker, L.J.; De Luca, A.; Juillerat-Jeanneret, L.; Morton, C.J.; Bello, M.L.; Parker, M.W.; Dyson, P.J. Rational design of an organometallic glutathione transferase inhibitor. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3854–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, A.E.; Hartinger, C.G.; Renfrew, A.K.; Dyson, P.J. Metabolization of [Ru(η6-C6H5CF 3)(pta)Cl 2]: A cytotoxic RAPTA-type complex with a strongly electron withdrawing arene ligand. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 15, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccioloni, M.; Bonfili, L.; Cecarini, V.; Nabissi, M.; Pettinari, R.; Marchetti, F.; Petrelli, R.; Cappellacci, L.; Angeletti, M.; Eleuteri, A.M. Exploring the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the in vitro Anticancer Effects of Multitarget-Directed Hydrazone Ruthenium(II)–Arene Complexes. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Zheng, C.; Le, F.; Qin, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J. Ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes: Cellular uptake, cell image and apoptosis of HeLa cancer cells induced by double targets. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 82, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedl, C.A.; Flocke, L.S.; Hejl, M.; Roller, A.; Klose, M.H.M.; Jakupec, M.A.; Kandioller, W.; Keppler, B.K. Introducing the 4-Phenyl-1,2,3-Triazole Moiety as a Versatile Scaffold for the Development of Cytotoxic Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) Arene Cyclometalates. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, F.J.; Ortega, E.; Porto, V.; Kostrhunova, H.; Davila-Ferreira, N.; Bautista, D.; Brabec, V.; Domínguez, F.; Santana, M.D.; Ruiz, J. New half-sandwich ruthenium(ii) complexes as proteosynthesis inhibitors in cancer cells. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 1140–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novohradsky, V.; Yellol, J.; Stuchlikova, O.; Santana, M.D.; Kostrhunova, H.; Yellol, G.; Kasparkova, J.; Bautista, D.; Ruiz, J.; Brabec, V. Organoruthenium Complexes with C^N Ligands are Highly Potent Cytotoxic Agents that Act by a New Mechanism of Action. Chem.-Eur. J. 2017, 23, 15294–15299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohata, J.; Ball, Z.T. Rhodium at the chemistry-biology interface. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 14855–14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.A.; Sherwood, E.; Erck, A.; Kimball, A.P.; Bear, J.L. Hydrophobicity of Several Rhodium(II) Carboxylates Correlated with Their Biologic Activity. J. Med. Chem. 1977, 20, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erck, A.; Rainen, L.; Whileyman, J.; Chang, I.-M.; Kimball, A.P.; Bear, J. Studies of Rhodium(I1) Carboxylates as Potential Antitumor Agents. Exp. Biol. Med. 1974, 145, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.H.; Yang, H.; Ma, V.P.Y.; Chan, D.S.H.; Zhong, H.J.; Li, Y.W.; Fong, W.F.; Ma, D.L. Inhibition of Janus kinase 2 by cyclometalated rhodium complexes. Medchemcomm 2012, 3, 696–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, M.; Saeedi, M.; Larijani, B.; Mahdavi, M. Recent advances in biological activities of rhodium complexes: Their applications in drug discovery research. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 216, 113308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salassa, L. Polypyridyl metal complexes with biological activity. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 4931–4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmacher, Y.; Splith, K.; Kitanovic, I.; Alborzinia, H.; Can, S.; Rubbiani, R.; Nazif, M.A.; Wefelmeier, P.; Prokop, A.; Ott, I.; et al. Cellular impact and selectivity of half-sandwich organorhodium(III) anticancer complexes and their organoiridium(III) and trichloridorhodium(III) counterparts. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 17, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldmacher, Y.; Kitanovic, I.; Alborzinia, H.; Bergerhoff, K.; Rubbiani, R.; Wefelmeier, P.; Prokop, A.; Gust, R.; Ott, I.; Wölfl, S.; et al. Cellular Selectivity and Biological Impact of Cytotoxic Rhodium(III) and Iridium(III) Complexes Containing Methyl-Substituted Phenanthroline Ligands. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobroschke, M.; Geldmacher, Y.; Ott, I.; Harlos, M.; Kater, L.; Wagner, L.; Gust, R.; Sheldrick, W.S.; Prokop, A. Cytotoxic rhodium(III) and iridium(III) polypyridyl Complexes: Structure-activity relationships, antileukemic activity, and apoptosis induction. ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlos, M.; Ott, I.; Gust, R.; Alborzinia, H.; Wölfl, S.; Kromm, A.; Sheldrick, W.S. Synthesis, biological activity, and structure-activity relationships for potent cytotoxic rhodium(III) polypyridyl complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 3924–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, E.J.; Barton, J.K. DNA oxidation by charge transport in mitochondria. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scharwitz, M.A.; Ott, I.; Geldmacher, Y.; Gust, R.; Sheldrick, W.S. Cytotoxic half-sandwich rhodium(III) complexes: Polypyridyl ligand influence on their DNA binding properties and cellular uptake. J. Organomet. Chem. 2008, 693, 2299–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmacher, Y.; Rubbiani, R.; Wefelmeier, P.; Prokop, A.; Ott, I.; Sheldrick, W.S. Synthesis and DNA-binding properties of apoptosis-inducing cytotoxic half-sandwich rhodium(III) complexes with methyl-substituted polypyridyl ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, L.E.; Aguirre, J.D.; Angeles-Boza, A.M.; Chouai, A.; Fu, P.K.L.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. Photophysical properties, DNA photocleavage, and photocytotoxicity of a series of Dppn dirhodium(II,II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 5371–5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, J.D.; Lutterman, D.A.; Angeles-Boza, A.M.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. Effect of axial coordination on the electronic structure and biological activity of dirhodium(II,II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 7494–7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Palepu, N.R.; Sutradhar, D.; Shepherd, S.L.; Phillips, R.M.; Kaminsky, W.; Chandra, A.K.; Kollipara, M.R. Neutral and cationic half-sandwich arene ruthenium, Cp*Rh and Cp*Ir oximato and oxime complexes: Synthesis, structural, DFT and biological studies. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 820, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldevila-Barreda, J.J.; Habtemariam, A.; Romero-Canelón, I.; Sadler, P.J. Half-sandwich rhodium(III) transfer hydrogenation catalysts: Reduction of NAD+ and pyruvate, and antiproliferative activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 153, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J.F.; Lu, C.C. Metal-Metal Bonds: From Fundamentals to Applications. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 7577–7581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, J.R.; Haromy, T.P.; Sundaralingam, M. Positional parameters for all non-H atoms and equivalent isotropic temperature factors. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 1991, 47, 1712–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlepes, S.P.; Huffman, J.C.; Matonic, J.H.; Dunbar, K.R.; Christou, G. Binding of 2,2′-Bipyridine to the Dirhodium(II) Tetraacetate Core: Unusual Structural Features and Biological Relevance of the Product Rh2(OAc)4(bpy). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 2770–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C.A.; Matonic, J.H.; Streib, W.E.; Huffman, J.C.; Dunbar, K.R.; Christou, G. Reaction of 2,2’-Bipyridine (bpy ) with Dirhodium Carboxylates: Mono-bpy Products with Variable Chelate Binding Modes and Insights into the Reaction Mechanism. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 3125–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, S.; Yokosawa, H. Targeting the proteasome pathway. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2009, 13, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernassola, F.; Ciechanover, A.; Melino, G. The ubiquitin proteasome system and its involvement in cell death pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aguirre, J.D.; Angeles-Boza, A.M.; Chouai, A.; Pellois, J.P.; Turro, C.; Dunbar, K.R. Live cell cytotoxicity studies: Documentation of the interactions of antitumor active dirhodium compounds with nuclear DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11353–11360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masternak, J.; Gilewska, A.; Kazimierczuk, K.; Khavryuchenko, O.V.; Wietrzyk, J.; Trynda, J.; Barszcz, B. Synthesis, physicochemical and theoretical studies on new rhodium and ruthenium dimers. Relationship between structure and cytotoxic activity. Polyhedron 2018, 154, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirajuddin, M.; Ali, S.; Badshah, A. Drug-DNA interactions and their study by UV-Visible, fluorescence spectroscopies and cyclic voltammetry. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2013, 124, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chifotides, H.T.; Lutterman, D.A.; Dunbar, K.R.; Turro, C. Insight into the photoinduced ligand exchange reaction pathway of cis -[Rh 2(μ-O 2CCH 3) 2(CH 3CN) 6] 2+ with a DNA model chelate. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 12099–12107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutterman, D.A.; Fu, P.K.L.; Turro, C. cis-[Rh2(μ-O2CCH3)2(CH 3CN)6]2+ as a photoactivated cisplatin analog. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 738–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; David, A.; Albani, B.A.; Pellois, J.P.; Turro, C.; Dunbar, K.R. Optimizing the electronic properties of photoactive anticancer oxypyridine-bridged dirhodium(II,II) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17058–17070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzotti, C.; Pratesi, G.; Menta, E.; Di Domenico, R.; Cavalletti, E.; Fiebig, H.H.; Kelland, L.R.; Farrell, N.; Polizzi, D.; Supino, R.; et al. BBR 3464: A Novel Triplatinum Complex, Exhibiting a Preclinical Profile of Antitumor Efficacy Different from Cisplatin 1. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 2626–2634. Available online: http://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article-pdf/6/7/2626/2077796/df070002626.pdf (accessed on 20 December 1999). [PubMed]

- Jodrell, D.I.; Evans, T.R.J.; Steward, W.; Cameron, D.; Prendiville, J.; Aschele, C.; Noberasco, C.; Lind, M.; Carmichael, J.; Dobbs, N.; et al. Phase II studies of BBR3464, a novel tri-nuclear platinum complex, in patients with gastric or gastro-oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2004, 40, 1872–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, S.; Hanif, M.; Leung, E.; Tong, K.K.H.; Yang, A.; Astin, J.; De Zoysa, G.H.; Steel, T.R.; Goodman, D.; Movassaghi, S.; et al. Anticancer organorhodium and -iridium complexes with low toxicity: In vivo but high potency in vitro: DNA damage, reactive oxygen species formation, and haemolytic activity. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 12016–12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Murray, B.S.; Dyson, P.J.; Therrien, B. Synthesis, molecular structure and cytotoxicity of molecular materials based on water soluble half-sandwich Rh(III) and Ir(III) tetranuclear metalla-cycles. Materials 2013, 6, 5352–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Kumar, J.M.; Garci, A.; Nagesh, N.; Therrien, B. Exploiting natural products to build metalla-assemblies: The anticancer activity of embelin-derived Rh(III) and Ir(III) metalla-rectangles. Molecules 2014, 19, 6031–6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.; Denoyelle-Di-Muro, E.; Mbakidi, J.P.; Leroy-Lhez, S.; Sol, V.; Therrien, B. Delivery of porphin to cancer cells by organometallic Rh(III) and Ir(III) metalla-cages. J. Organomet. Chem. 2015, 787, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Kumar, J.M.; Garci, A.; Rangaraj, N.; Nagesh, N.; Therrien, B. Anticancer activity of half-sandwich RhIII and IrIII metalla-prisms containing lipophilic side chains. ChemPlusChem 2014, 79, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.; Oggu, G.S.; Nagesh, N.; Bokara, K.K.; Therrien, B. Anticancer activity of large metalla-assemblies built from half-sandwich complexes. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 4952–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao A, B.P.; Uma, A.; Chiranjeevi, T.; Bethu, M.S.; Rao J, V.; Deb, D.K.; Sarkar, B.; Kaminsky, W.; Kollipara, M.R. The in vitro antitumor activity of oligonuclear polypyridyl rhodium and iridium complexes against cancer cells and human pathogens. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 824, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Garci, A.; Murray, B.S.; Dyson, P.J.; Fabre, G.; Trouillas, P.; Giannini, F.; Furrer, J.; Süss-Fink, G.; Therrien, B. Synthesis, molecular structure, computational study and in vitro anticancer activity of dinuclear thiolato-bridged pentamethylcyclopentadienyl Rh(iii) and Ir(iii) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 15457–15463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnpeter, J.P.; Gupta, G.; Kumar, J.M.; Srinivas, G.; Nagesh, N.; Therrien, B. Biological studies of chalcogenolato-bridged dinuclear half-sandwich complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 13663–13673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Murray, B.S.; Dyson, P.J.; Therrien, B. Highly cytotoxic trithiolato-bridged dinuclear Rh(III) and Ir(III) complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2014, 767, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldmacher, Y.; Oleszak, M.; Sheldrick, W.S. Rhodium(III) and iridium(III) complexes as anticancer agents. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2012, 393, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sadler, P.J. Organoiridium complexes: Anticancer agents and catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.L.; Chan, D.S.H.; Leung, C.H. Group 9 organometallic compounds for therapeutic and bioanalytical applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3614–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sava, G.; Zorzet, S.; Perissin, L.; Mestroni, G.; Zassinovich, G.; Bontempi, A. Coordination Metal Complexes of Rh(I), Ir(1) and Ru(I1): Recent Advances on Antimetastatic Activity on Solid Mouse Tumors. Inorganica Chim. Acta 1987, 137, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldi, T.; Sava, G.; Mestroni, G.; Zassinovich, G.; Stolfa, D. Antitumour Action of Rhodium (I) and Iridium (I) Complexes. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 1978, 22, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Habtemariam, A.; Pizarro, A.M.; Fletcher, S.A.; Kisova, A.; Vrana, O.; Salassa, L.; Bruijnincx, P.C.A.; Clarkson, G.J.; Brabec, V.; et al. Organometallic half-sandwich iridium anticancer complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3011–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Salassa, L.; Habtemariam, A.; Pizarro, A.M.; Clarkson, G.J.; Sadler, P.J. Contrasting reactivity and cancer cell cytotoxicity of isoelectronic organometallic iridium(III) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 5777–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Habtemariam, A.; Pizarro, A.M.; Clarkson, G.J.; Sadler, P.J. Organometallic iridium(III) cyclopentadienyl anticancer complexes containing C,N-Chelating ligands. Organometallics 2011, 30, 4702–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Romero-Canelón, I.; Habtemariam, A.; Clarkson, G.J.; Sadler, P.J. Potent half-sandwich iridium(III) anticancer complexes containing C^N-chelated and pyridine ligands. Organometallics 2014, 33, 5324–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trachootham, D.; Alexandre, J.; Huang, P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: A radical therapeutic approach? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunley, G.J.; Watson, D.J. High productivity methanol carbonylation catalysis using iridium The Cativa TM process for the manufacture of acetic acid. Catal. Today 2000, 58, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, J.D.; Schley, N.D.; Olack, G.W.; Incarvito, C.D.; Brudvig, G.W.; Crabtree, R.H. Anodic deposition of a robust iridium-based water-oxidation catalyst from organometallic precursors. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, A.; Bellachioma, G.; Ciancaleoni, G.; Zuccaccia, C.; Zuccaccia, D.; MacChioni, A. Iridium(iii) molecular catalysts for water oxidation: The simpler the faster. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 9218–9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.F.; Himeda, Y.; Wang, W.H.; Hashiguchi, B.; Periana, R.; Szalda, D.J.; Muckerman, J.T.; Fujita, E. Reversible hydrogen storage using CO2 and a proton-switchable iridium catalyst in aqueous media under mild temperatures and pressures. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, R.; Punji, B.; Findlater, M.; Supplee, C.; Schinski, W.; Brookhart, M.; Goldman, A.S. Catalytic dehydroaromatization of n-alkanes by pincer-ligated iridium complexes. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewster, T.P.; Blakemore, J.D.; Schley, N.D.; Incarvito, C.D.; Hazari, N.; Brudvig, G.W.; Crabtree, R.H. An iridium(IV) species, [Cp*Ir(NHC)Cl]+, related to a water-oxidation catalyst. Organometallics 2011, 30, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Deeth, R.J.; Butler, J.S.; Habtemariam, A.; Newton, M.E.; Sadler, P.J. Reduction of quinones by NADH catalyzed by organoiridium complexes. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4194–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betanzos-Lara, S.; Liu, Z.; Habtemariam, A.; Pizarro, A.M.; Qamar, B.; Sadler, P.J. Organometallic ruthenium and iridium transfer-hydrogenation catalysts using coenzyme NADH as a cofactor. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3897–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Romero-Canelõn, I.; Qamar, B.; Hearn, J.M.; Habtemariam, A.; Barry, N.P.E.; Pizarro, A.M.; Clarkson, G.J.; Sadler, P.J. The potent oxidant anticancer activity of organoiridium catalysts. Angew. Chem.- Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3941–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velema, W.A.; Szymanski, W.; Feringa, B.L. Photopharmacology: Beyond proof of principle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2178–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Huang, P.; Chen, X. Overcoming the Achilles’ heel of photodynamic therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 6488–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oszajca, M.; Brindell, M.; Orzeł, Ł.; Dąbrowski, J.M.; Śpiewak, K.; Łabuz, P.; Pacia, M.; Stochel-Gaudyn, A.; Macyk, W.; van Eldik, R.; et al. Mechanistic studies on versatile metal-assisted hydrogen peroxide activation processes for biomedical and environmental incentives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 327–328, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, J.P.; Spring, B.Q.; Rizvi, I.; Evans, C.L.; Samkoe, K.S.; Verma, S.; Pogue, B.W.; Hasan, T. Imaging and photodynamic therapy: Mechanisms, monitoring, and optimization. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2795–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissleder, R. A clearer vision for in vivo imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormond, A.B.; Freeman, H.S. Dye sensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Materials 2013, 6, 817–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, I.; Li, J.Z.; Shim, Y.K. Advance in photosensitizers and light delivery for photodynamic therapy. Clin. Endosc. 2013, 46, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guan, R.; Zhang, C.; Huang, J.; Ji, L.; Chao, H. Two-photon luminescent metal complexes for bioimaging and cancer phototherapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 310, 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Gai, L.; Zhou, Z.; Mack, J.; Xu, K.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, H.; Chan, K.S.; Shen, Z. Highly efficient near IR photosensitizers based-on Ir-C bonded porphyrin-aza-BODIPY conjugates. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 72115–72120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, B. Transporting and shielding photosensitisers by using water-soluble organometallic cages: A new strategy in drug delivery and photodynamic therapy. Chem.-Eur. J. 2013, 19, 8378–8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, S.S.; Bennett, J.; Coleman, J.; Grubb, R.; Andriole, G.; Reiter, R.E.; Marks, L.; Azzouzi, A.R.; Emberton, M. Final Results of a Phase I/II Multicenter Trial of WST11 Vascular Targeted Photodynamic Therapy for Hemi-Ablation of the Prostate in Men with Unilateral Low Risk Prostate Cancer Performed in the United States. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waern, J.B.; Desmarets, C.; Chamoreau, L.M.; Amouri, H.; Barbieri, A.; Sabatini, C.; Ventura, B.; Barigelletti, F. Luminescent cyclometalated RhIII, IrIII, and (DIP)2RuII complexes with carboxylated bipyridyl ligands: Synthesis, x-ray molecular structure, and photophysical properties. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 3340–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y. Phosphorescence bioimaging using cyclometalated Ir(III) complexes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Ho, D.G.; Hernandez, B.; Selke, M.; Murphy, D.; Djurovich, P.I.; Thompson, M.E. Bis-cyclometalated Ir(III) complexes as efficient singlet oxygen sensitizers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 14828–14829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, K.Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Xu, A.; Guo, S.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, W. A Mitochondria-Targeted Photosensitizer Showing Improved Photodynamic Therapy Effects Under Hypoxia. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 10101–10105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.R.; Hay, M.P. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Ding, L.; Xu, H.J.; Shen, Z.; Ju, H.; Jia, L.; Bao, L.; Yu, J.S. Cell-specific and pH-activatable rubyrin-loaded nanoparticles for highly selective near-infrared photodynamic therapy against cancer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18850–18858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.D.; Kong, X.; He, S.F.; Chen, J.X.; Sun, J.; Chen, B.B.; Zhao, J.W.; Mao, Z.W. Cyclometalated iridium(III)-guanidinium complexes as mitochondria-targeted anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Zeng, L.; Huang, H.; Jin, C.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Ji, L.; Chao, H. Fluorinated cyclometalated iridium(III) complexes as mitochondria-targeted theranostic anticancer agents. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 6734–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Poria, D.K.; Ghosh, R.; Ray, P.S.; Gupta, P. Development of a cyclometalated iridium complex with specific intramolecular hydrogen-bonding that acts as a fluorescent marker for the endoplasmic reticulum and causes photoinduced cell death. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 17463–17474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.S.; Kang, M.G.; Kang, J.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, S.J.C.; Kim, H.T.; Seo, J.K.; Kwon, O.H.; Lim, M.H.; Rhee, H.W.; et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum-Localized Iridium(III) Complexes as Efficient Photodynamic Therapy Agents via Protein Modifications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10968–10977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.J.; Tan, C.P.; Chen, M.H.; Wu, N.; Yao, D.Y.; Liu, X.G.; Ji, L.N.; Mao, Z.W. Targeting cancer cell metabolism with mitochondria-immobilized phosphorescent cyclometalated iridium(iii) complexes. Chem. Sci. 2016, 8, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Chen, Y.; Ouyang, C.; Guan, R.L.; Ji, L.N.; Chao, H. Cyclometalated iridium(III) complexes as mitochondria-targeted anticancer agents. Biochimie 2016, 125, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.X.; Chen, M.H.; Hu, X.Y.; Ye, R.R.; Tan, C.P.; Ji, L.N.; Mao, Z.W. Ester-Modified Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes as Mitochondria-Targeting Anticancer Agents. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.R.; Tan, C.P.; Ji, L.N.; Mao, Z.W. Coumarin-appended phosphorescent cyclometalated iridium(III) complexes as mitochondria-targeted theranostic anticancer agents. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 13042–13051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.H.; Wang, F.X.; Cao, J.J.; Tan, C.P.; Ji, L.N.; Mao, Z.W. Light-Up Mitophagy in Live Cells with Dual-Functional Theranostic Phosphorescent Iridium(III) Complexes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13304–13314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, R.R.; Cao, J.J.; Tan, C.P.; Ji, L.N.; Mao, Z.W. Valproic Acid-Functionalized Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Complexes as Mitochondria-Targeting Anticancer Agents. Chem.-Eur. J. 2017, 23, 15166–15176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.J.; Wang, W.; Huang, S.Y.; Hong, Y.; Li, G.; Lin, S.; Tian, J.; Cai, Z.; Wang, H.M.D.; Ma, D.L.; et al. Inhibition of the Ras/Raf interaction and repression of renal cancer xenografts in vivo by an enantiomeric iridium(III) metal-based compound. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4756–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.A.; Khuri, F.R.; Fu, H. Targeting protein-protein interactions as an anticancer strategy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, K.K.S.; Leung, K.K.; Liu, H.W.; Lo, K.K.W. Photoactivatable cytotoxic agents derived from mitochondria-targeting luminescent iridium(III) poly(ethylene glycol) complexes modified with a nitrobenzyl linkage. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4557–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidova, A.; Pierroz, V.; Rubbiani, R.; Lan, Y.; Schmitz, A.G.; Kaech, A.; Sigel, R.K.O.; Ferrari, S.; Gasser, G. Photo-induced uncaging of a specific Re(i) organometallic complex in living cells. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4044–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.; Pierroz, V.; Mari, C.; Gemperle, L.; Ferrari, S.; Gasser, G. A Bis(dipyridophenazine)(2-(2-pyridyl)pyrimidine-4-carboxylic acid)ruthenium(II) Complex with Anticancer Action upon Photodeprotection. Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 3004–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Rhodium (Rh) Complexes | Iridium (Ir) Complexes |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of action |

|

|

| Selectivity | High (catalytic activation possible in the tumour environment) | High in the case of photoactivation; moderate without it |

| Pharmacokinetics | High stability in plasma; possible binding to transferrin; active transport to cells | High lipophilicity, and accumulation in mitochondria and liver; slow elimination |

| Toxicity | Low; possible mild metabolic disturbances and oxidative stress | Potential hepatotoxicity and mitochondrial toxicity (dose-dependent and light-dependent) |

| Stage of research | Preclinical; several compounds in early biological testing | Preclinical; in vitro and in vivo testing, PDT/PACT concept development and bioimaging |

| Therapeutic potential | Very high—due to new MoA and lower toxicity | High—possibility of photocontrol and selectivity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gilewska, A.; Barszcz, B.; Masternak, J. Review of the Most Important Research Trends in Potential Chemotherapeutics Based on Coordination Compounds of Ruthenium, Rhodium and Iridium. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111728

Gilewska A, Barszcz B, Masternak J. Review of the Most Important Research Trends in Potential Chemotherapeutics Based on Coordination Compounds of Ruthenium, Rhodium and Iridium. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111728

Chicago/Turabian StyleGilewska, Agnieszka, Barbara Barszcz, and Joanna Masternak. 2025. "Review of the Most Important Research Trends in Potential Chemotherapeutics Based on Coordination Compounds of Ruthenium, Rhodium and Iridium" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111728

APA StyleGilewska, A., Barszcz, B., & Masternak, J. (2025). Review of the Most Important Research Trends in Potential Chemotherapeutics Based on Coordination Compounds of Ruthenium, Rhodium and Iridium. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111728