Lithium Point-of-Care Testing to Improve Adherence to Monitoring Guidelines and Quality of Maintenance Therapy: Protocol for a Randomised Feasibility Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

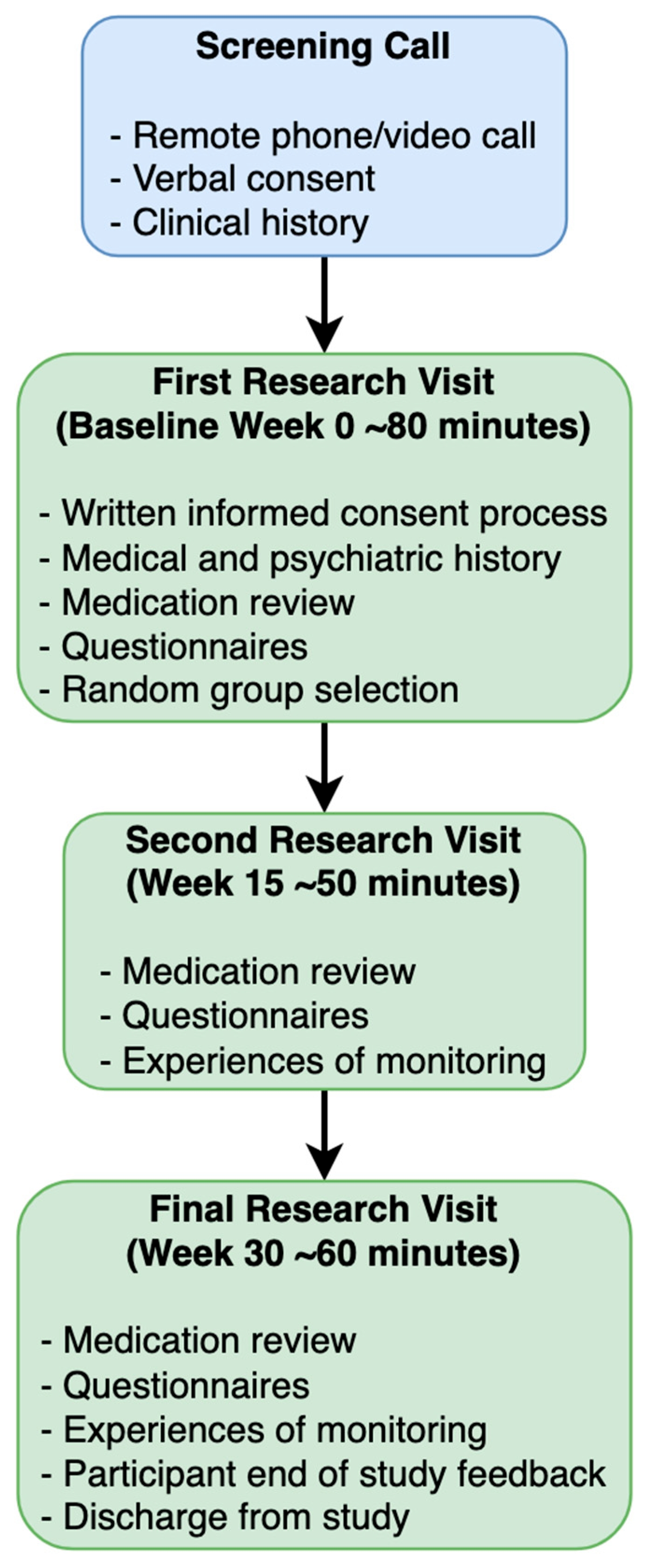

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Intervention

2.4.1. POC Testing

2.4.2. TAU

2.5. Randomisation and Blinding

2.6. Outcomes

- Feasibility

- Participant recruitment rates over the trial period.

- Participant retention and completion rates over 30 weeks.

- Rates of lithium discontinuation over 30 weeks.

- Adherence to lithium monitoring guidelines (proportion of participants meeting NICE guidelines for frequency testing and lithium levels within therapeutic range) over 30 weeks.

- Patient acceptability

- Patient monitoring acceptability questionnaires at week 15 and week 30.

- Patient preferences for POC testing versus laboratory testing.

- Perceived usefulness of POC monitoring.

- Contamination bias

- Monitoring rates between treatment-exposed versus non-exposed services.

- Changes in monitoring rates from first to last patients recruited.

- Participants’ monitoring rates from before trial (from electronic health records) versus during the trial.

- Clinician survey about service changes during the trial.

- Costs and economic outcomes

- Mood and affective symptoms

- Side effects and adverse events

- Lithium side-effects rating scale (LiSERS) [25] at weeks 15 and 30.

- Adverse events over 30 weeks.

2.7. Statistics

2.8. Trial Oversight

2.9. Data Security and Management

2.10. Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

2.11. Dissemination

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATE | Allowable Total Error |

| BD | Bipolar Disorder |

| CNTW | Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust |

| CNWL | Central and North West London NHS Trust |

| CSRI | Client Service Receipt Inventory |

| EQ-5D | EuroQol-5D |

| FAST-R | Feasibility and Acceptability Support Team for Researchers |

| GCP | Good Clinical Practice |

| ITT | Intention to Treat |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LEAP | Lived Experience Advisory Panel |

| LiSERS | Lithium Side-Effects Rating Scale |

| M3VAS | Maudsley Visual Analogue Scales |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| mmol/L | Millimoles Per Litre |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| POC | Point of Care |

| RCT | Randomised Controlled Trial |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SLaM | South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust |

| SWLSTG | South West London & St George’s NHS Trust |

| TAU | Treatment As Usual |

| TSC | Trial Steering Committee |

| WLNHS | West London NHS Trust |

| YMRS | Young Mania Rating Scale |

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar Disorder: Assessment and Management [CG185]. 2025. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in Adults: Treatment and Management [NG222]. 2022. Available online: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Severus, W.; Kleindienst, N.; Seemüller, F.; Frangou, S.; Möller, H.; Greil, W. What Is the Optimal Serum Lithium Level in the Long-term Treatment of Bipolar Disorder—A Review? Bipolar Disord. 2008, 10, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, M. Lithium Side Effects and Toxicity: Prevalence and Management Strategies. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2016, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla, I.; Lopez-Zurbano, S.; Alberich, S.; Barbero, I.; Lopez-Pena, P.; García-Corres, E.; Chart Pascual, J.P.; Crespo, J.M.; De Dios, C.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; et al. Lithium Levels and Lifestyle in Patients with Bipolar Disorder: A New Tool for Self-Management. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2023, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.; Barnes, T.R.; Shingleton-Smith, A.; Gerrett, D.; Paton, C. Standards of Lithium Monitoring in Mental Health Trusts in the UK. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Patient Safety Agency. Safer Lithium Therapy [NPSA/2009/PSA005]. 2009. Available online: https://www.cas.mhra.gov.uk/ViewandAcknowledgment/ViewAlert.aspx?AlertID=101306 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Paton, C.; Adroer, R.; Barnes, T.R. Monitoring Lithium Therapy: The Impact of a Quality Improvement Programme in the UK. Bipolar Disord. 2013, 15, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolova, V.L.; Pattanaseri, K.; Hidalgo-Mazzei, D.; Taylor, D.; Young, A.H. Is Lithium Monitoring NICE? Lithium Monitoring in a UK Secondary Care Setting. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uskur, T.; Güven, O.; Tat, M. Retrospective Analysis of Lithium Treatment: Examination of Blood Levels. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1414424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederlof, M.; Egberts, T.C.; Van Londen, L.; De Rotte, M.C.; Souverein, P.C.; Herings, R.M.; Heerdink, E.R. Compliance with the Guidelines for Laboratory Monitoring of Patients Treated with Lithium: A Retrospective Follow-up Study among Ambulatory Patients in the Netherlands. Bipolar Disord. 2019, 21, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchfield, I.; Bentham, L.; Hill, A.; McManus, R.J.; Lilford, R.; Greenfield, S. Routine failures in the process for blood testing and the communication of results to patients in primary care in the UK: A qualitative exploration of patient and provider perspectives. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchfield, I.; Bentham, L.; Lilford, R.; McManus, R.J.; Hill, A.; Greenfield, S. Test result communication in primary care: A survey of current practice. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Mazzei, D.; Mantingh, T.; Pérez de Mendiola, X.; Samalin, L.; Undurraga, J.; Strejilevich, S.; Severus, E.; Bauer, M.; González-Pinto, A.; Nolen, W.A.; et al. Clinicians’ preferences and attitudes towards the use of lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders around the world: A survey from the ISBD Lithium task force. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2023, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Bell, E.; Jadidi, M.; Gitlin, M.; Bauer, M. Countering the declining use of lithium therapy: A call to arms. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2023, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olansky, L.; Kennedy, L. Finger-Stick Glucose Monitoring. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 948–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.; Taylor, D.; Harland, R.; Brewer, A.; Williams, S.; Chesney, E.; McGuire, P. Acceptability of Point of Care Testing for Antipsychotic Medication Levels in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care Quality Commission. South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust: Inspection Report. 2021. Available online: https://api.cqc.org.uk/public/v1/reports/4a1743ed-a98a-4b9a-adfa-7bfa83639c77?20221129062700 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Young, R.C.; Biggs, J.T.; Ziegler, V.E.; Meyer, D.A. A Rating Scale for Mania: Reliability, Validity and Sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 133, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staal, S.; Ungerer, M.; Floris, A.; Ten Brinke, H.; Helmhout, R.; Tellegen, M.; Janssen, K.; Karstens, E.; Van Arragon, C.; Lenk, S.; et al. A Versatile Electrophoresis-based Self-test Platform. Electrophoresis 2015, 36, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and Preliminary Testing of the New Five-Level Version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beecham, J.; Knapp, M. Costing Psychiatric Interventions. In Measuring Mental Health Needs; Gaskell: London, UK, 1999; pp. 200–224. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Åsberg, M. A New Depression Scale Designed to Be Sensitive to Change. Br. J. Psychiatry 1979, 134, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulton, C.D.; Strawbridge, R.; Tsapekos, D.; Oprea, E.; Carter, B.; Hayes, C.; Cleare, A.J.; Marwood, L.; Mantingh, T.; Young, A.H. The Maudsley 3-Item Visual Analogue Scale (M3VAS): Validation of a Scale Measuring Core Symptoms of Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, P.; Wieck, A.; Yarrow, M.; Denham, P. The Lithium Side Effects Rating Scale (LISERS); Development of a Self-Rating Instrument. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999, 9, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Additional Guidance For Applicants Including a Clinical Trial, Pilot Study or Feasibility as Part of a Personal Award Application. 2019. Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/additional-guidance-applicants-including-clinical-trial-pilot-study-or-feasibility-part-personal-award-application (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Kessing, L.V. Why is lithium [not] the drug of choice for bipolar disorder? A controversy between science and clinical practice. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2024, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Procedures/Measures | Screening (Pre-Study) | Baseline (W0) | Follow-Up 1 (W15) | Follow-Up 2 (W30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent process | X | X | ||

| Medical and psychiatric information | X | X | ||

| Sociodemographic information | X | X | ||

| Medication and lithium review | X | X | X | X |

| Randomisation | X | |||

| EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) | X | X | X | |

| Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) | X | X | X | |

| Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) | X | X | X | X |

| Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) | X | X | X | |

| Maudsley visual analogue scales (M3VAS) | X | X | X | |

| Lithium side-effects rating scale (LiSERS) | X | X | X | |

| Patient monitoring acceptability questionnaire | X | X | X | |

| Participant end of study feedback questions | X |

| Go—Proceed with RCT | Amend—Proceed with Changes | Stop—Do Not Proceed Unless Changes Are Possible | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant recruitment | 80 in 12 months | 80 reached but in >12 months | 53 not reached by 12 months |

| POC monitoring acceptability | ≥80% rating POC as “acceptable” | 30–79% rating POC as “acceptable” | <30% rating POC as “acceptable” |

| Participant attrition rate | ≤20% attrition | 21–50% attrition | >50% attrition |

| Adherence to lithium monitoring guidelines | >60% adherence | 30–60% adherence | <30% adherence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kerr-Gaffney, J.; Prakash, P.; Wing, V.C.; Young, A.H.; Kavanagh, O.N.; Hodsoll, J.; Markham, S.; Cousins, D.A.; Hampsey, E.; Jauhar, S.; et al. Lithium Point-of-Care Testing to Improve Adherence to Monitoring Guidelines and Quality of Maintenance Therapy: Protocol for a Randomised Feasibility Trial. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111683

Kerr-Gaffney J, Prakash P, Wing VC, Young AH, Kavanagh ON, Hodsoll J, Markham S, Cousins DA, Hampsey E, Jauhar S, et al. Lithium Point-of-Care Testing to Improve Adherence to Monitoring Guidelines and Quality of Maintenance Therapy: Protocol for a Randomised Feasibility Trial. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111683

Chicago/Turabian StyleKerr-Gaffney, Jess, Priyanka Prakash, Victoria C. Wing, Allan H. Young, Oisín N. Kavanagh, John Hodsoll, Sarah Markham, David A. Cousins, Elliot Hampsey, Sameer Jauhar, and et al. 2025. "Lithium Point-of-Care Testing to Improve Adherence to Monitoring Guidelines and Quality of Maintenance Therapy: Protocol for a Randomised Feasibility Trial" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111683

APA StyleKerr-Gaffney, J., Prakash, P., Wing, V. C., Young, A. H., Kavanagh, O. N., Hodsoll, J., Markham, S., Cousins, D. A., Hampsey, E., Jauhar, S., Taylor, D., Cleare, A. J., & Strawbridge, R. (2025). Lithium Point-of-Care Testing to Improve Adherence to Monitoring Guidelines and Quality of Maintenance Therapy: Protocol for a Randomised Feasibility Trial. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111683