Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of the First 2-Alkynyl(aza)indole 18F Probe Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregates

Abstract

1. Introduction

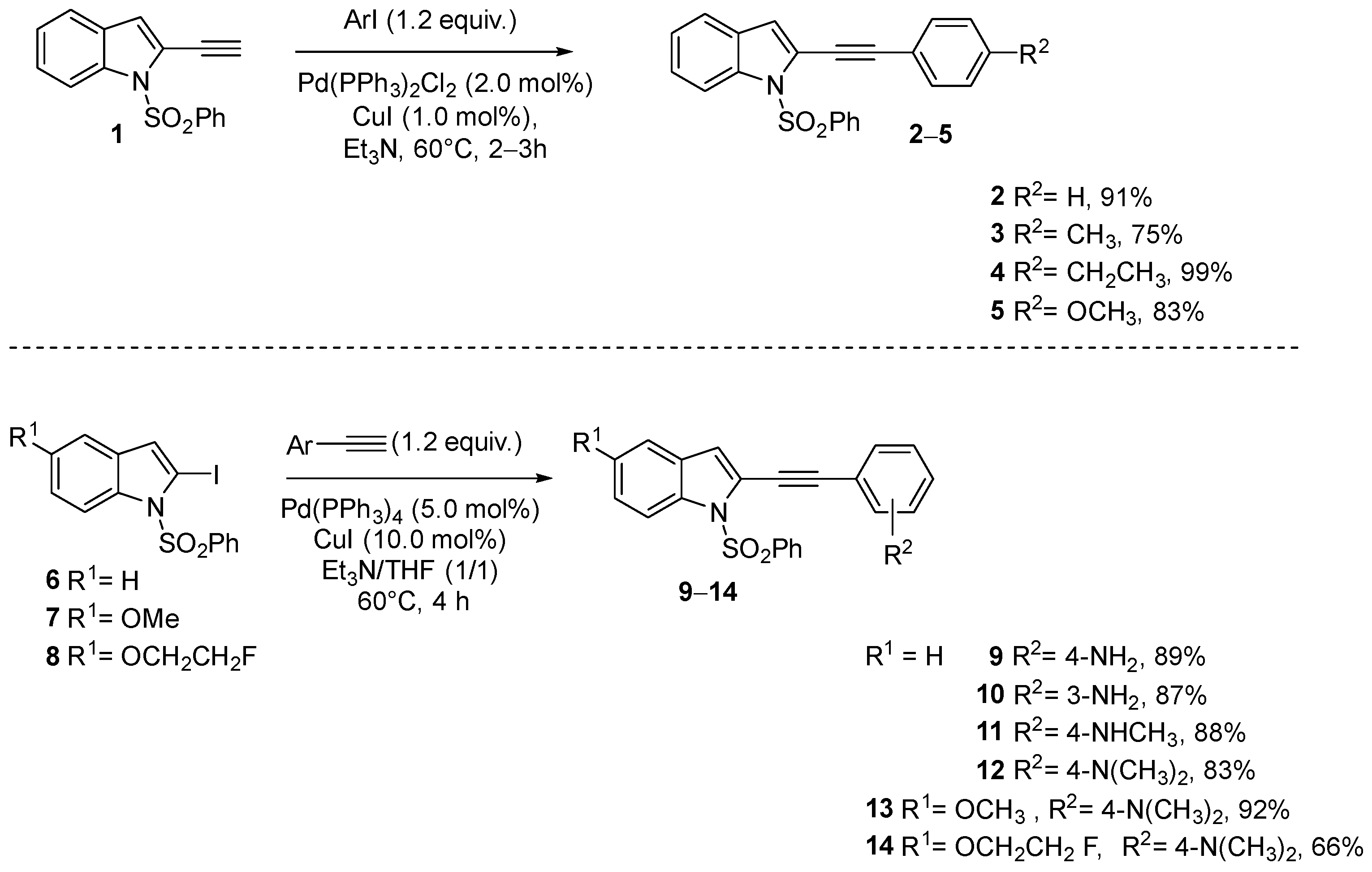

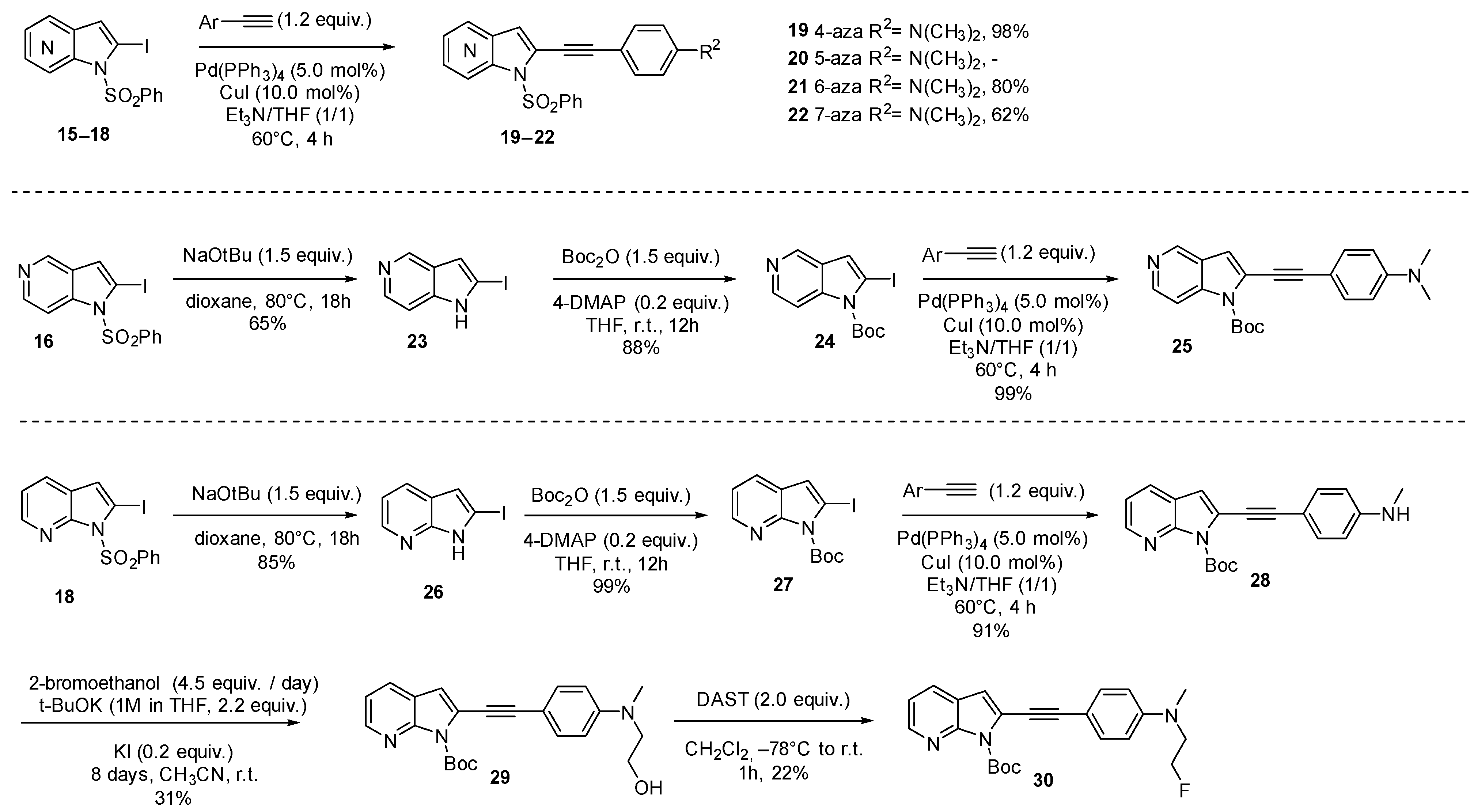

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. In Vitro Binding Experiments

2.2. Preparation of [18F]45

2.3. In Vivo Experiments

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. In Vitro Experiments

3.2.1. Expression and Purification of Recombinant α-Syn, Aβ1-42 and Tau

3.2.2. Production and Characterization of α-Syn, Aβ1-42, and Tau Fibrils

3.2.3. In Vitro Inhibition of Thioflavin T Binding and Ki Determination

3.2.4. In Vitro Fluorescence Titration Assays: Kd and Bmax Determination

3.3. Preparation of the Precursor and [18F]45

- tert-Butyl 2-((4-(methyl(2-(tosyloxy)ethyl)amino)phényl)éthynyl)-1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine-1-carboxylate 46

3.4. In Vivo Experiments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pemberton, H.G.; Collij, L.E.; Heeman, F.; Bollack, A.; Shekari, M.; Salvadó, G.; Alves, I.L.; Garcia, D.V.; Battle, M.; Buckley, C.; et al. Quantification of amyloid PET for future clinical use: A state-of-the-art review. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 3508–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, A.C.; Tissot, C.; Therriault, J.; Servaes, S.; Wang, Y.-T.; Fernandez-Arias, J.; Rahmouni, N.; Lussier, F.Z.; Vermeiren, M.; Bezgin, G.; et al. The Use of Tau PET to Stage Alzheimer Disease According to the Braak Staging Framework. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Cui, M. Current Progress in the Development of Probes for Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregates. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzghool, O.M.; van Dongen, G.; van de Giessen, E.; Schoonmade, L.; Beaino, W. α-Synuclein Radiotracer Development and In Vivo Imaging: Recent Advancements and New Perspectives. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.C.; Krainc, D. α-synuclein toxicity in neurodegeneration: Mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peelaerts, W.; Bousset, L.; Baekelandt, V.; Melki, R. α-Synuclein strains and seeding in Parkinson’s disease, incidental Lewy body disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy: Similarities and differences. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 373, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, S.E.; Siderowf, A.D. Current Status of α-Synuclein Biomarkers and the Need for α-Synuclein PET Tracers. Cells 2025, 14, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, S.; Ye, K. Positron emission tomography tracers for synucleinopathies. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xiang, J.; Ye, K.; Zhang, Z. Development of Positron Emission Tomography Radiotracers for Imaging α-Synuclein Aggregates. Cells 2025, 14, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, Y.; Okamura, N.; Furumoto, S.; Tashiro, M.; Furukawa, K.; Maruyama, M.; Itoh, M.; Iwata, R.; Yanai, K.; Arai, H. 2-(2-[2-Dimethylaminothiazol-5-yl]ethenyl)-6-(2-[fluoro]ethoxy)benzoxazole: A Novel PET Agent for In Vivo Detection of Dense Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodero-Tavoletti, M.T.; Mulligan, R.S.; Okamura, N.; Furumoto, S.; Rowe, C.C.; Kudo, Y.; Masters, C.L.; Cappai, R.; Yanai, K.; Villemagne, V.L. In vitro characterisation of BF227 binding to α-synuclein/Lewy bodies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 617, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levigoureux, E.; Lancelot, S.; Bouillot, C.; Chauveau, F.; Verdurand, M.; Verchere, J.; Billard, T.; Baron, T.; Zimmer, L. Binding of the PET Radiotracer [18F]BF227 Does not Reflect the Presence of Alpha-Synuclein Aggregates in Transgenic Mice. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2014, 11, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdurand, M.; Levigoureux, E.; Zeinyeh, W.; Berthier, L.; Mendjel-Herda, M.; Cadarossanesaib, F.; Bouillot, C.; Iecker, T.; Terreux, R.; Lancelot, S.; et al. In Silico, in Vitro, and in Vivo Evaluation of New Candidates for α-Synuclein PET Imaging. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 3153–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, A.; Leonov, A.; Ryazanov, S.; Herfert, K.; Kuebler, L.; Buss, S.; Schmidt, F.; Weckbecker, D.; Linder, R.; Bender, D.; et al. 11C Radiolabeling of anle253b: A Putative PET Tracer for Parkinson’s Disease That Binds to α-Synuclein Fibrils in vitro and Crosses the Blood-Brain Barrier. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuebler, L.; Buss, S.; Leonov, A.; Ryazanov, S.; Schmidt, F.; Maurer, A.; Weckbecker, D.; Landau, A.M.; Lillethorup, T.P.; Bleher, D.; et al. [11C]MODAG-001—Towards a PET tracer targeting α-synuclein aggregates. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 1759–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Zhou, D.; Gaba, V.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Peng, X.; Xu, J.; Dhavale, D.; Bagchi, D.P.; d’Avignon, A.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of 3-(Benzylidene)indolin-2-one Derivatives as Ligands for α-Synuclein Fibrils. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 6002–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Cui, J.; Padakanti, P.K.; Engel, L.; Bagchi, D.P.; Kotzbauer, P.T.; Tu, Z. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of α-synuclein ligands. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 4625–4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, D.P.; Yu, L.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Xu, J.; Mach, R.H.; Tu, Z.; Kotzbauer, P.T. Binding of the Radioligand SIL23 to α-Synuclein Fibrils in Parkinson Disease Brain Tissue Establishes Feasibility and Screening Approaches for Developing a Parkinson Disease Imaging Agent. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, H.; Padakanti, P.K.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Fan, J.; Mach, R.H.; Kotzbauer, P.; Tu, Z. Radiosynthesis and in Vivo Evaluation of Two PET Radioligands for Imaging α-Synuclein. Appl. Sci. 2014, 4, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaide, S.; Watanabe, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Iikuni, S.; Nakamoto, Y.; Hasegawa, M.; Itoh, K.; Ono, M. Identification and Evaluation of Bisquinoline Scaffold as a New Candidate for α-Synuclein-PET Imaging. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 4254–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaide, S.; Watanabe, H.; Iikuni, S.; Hasegawa, M.; Ono, M. Synthesis and Evaluation of 18F-Labeled Chalcone Analogue for Detection of α-Synuclein Aggregates in the Brain Using the Mouse Model. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 2982–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Chia, W.K.; Hsieh, C.-J.; Saturnino Guarino, D.; Graham, T.J.A.; Lengyel-Zhand, Z.; Schneider, M.; Tomita, C.; Lougee, M.G.; Kim, H.J.; et al. A Novel Brain PET Radiotracer for Imaging Alpha Synuclein Fibrils in Multiple System Atrophy. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 12185–12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nanni, A.; Saw, R.S.; Battisti, U.M.; Bowden, G.D.; Boeckermann, A.; Bjerregaard-Andersen, K.; Pichler, B.J.; Herfert, K.; Herth, M.M.; Maurer, A. A Fluorescent Probe as a Lead Compound for a Selective α-Synuclein PET Tracer: Development of a Library of 2-Styrylbenzothiazoles and Biological Evaluation of [18F]PFSB and [18F]MFSB. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 31450–31467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Tao, Y.; Xia, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Xia, W.; Zhang, M.; et al. Development of an α-synuclein positron emission tomography tracer for imaging synucleinopathies. Cell 2023, 186, 3350–3367.e3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosse, G. Novel Pyrrolo-pyrazol-one Ligands of Alpha-Synuclein for Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Dai, J.; Yan, X.-x.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Cui, M. Discovery and Evaluation of Imidazo[2,1-b][1,3,4]thiadiazole Derivatives as New Candidates for α-Synuclein PET Imaging. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 12695–12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Numata, A.; Saitoh, H.; Kondo, Y. Synthesis of β- and γ-Carbolines and Their N-Oxides from 2(or 3)-Ethynylindole-3(or 2)-carbaldehydes. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 47, 1740–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandanese, V.; Bottalico, D.; Marchese, G.; Punzi, A. A rapid synthesis of 2-alkynylindoles and 2-alkynylbenzofurans. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 7301–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, T.; Higashi, J.; Ito, S.; Okujima, T.; Yasunami, M.; Morita, N. Synthesis of Redox-Active, Intramolecular Charge-Transfer Chromophores by the [2+2] Cycloaddition of Ethynylated 2H-Cyclohepta[b]furan-2-ones with Tetracyanoethylene. Chem. A Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5116–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, B.t.; Da Costa, H.; Mérour, J.-Y.; Léonce, S. Synthesis of Pyrido[2,3-b]indole Derivatives via Diels–Alder Reactions of 2- and 3-Vinylpyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridines. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 3189–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefoix, M.; Daillant, J.-P.; Routier, S.; Mérour, J.-Y.; Gillaizeau, I.; Coudert, G. Versatile and Convenient Methods for the Synthesis of C-2 and C-3 Functionalised 5-Azaindoles. Synthesis 2005, 2005, 3581–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak, M.; Bilska-Markowska, M. Diethylaminosulfur Trifluoride (DAST) Mediated Transformations Leading to Valuable Building Blocks and Bioactive Compounds. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5585–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Chu, W.; Xu, J.; Schwarz, S.; Katzenellenbogen, J.A. [18F]Tosyl fluoride as a versatile [18F]fluoride source for the preparation of 18F-labeled radiopharmaceuticals. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghee, M.; Melki, R.; Michot, N.; Mallet, J. PA700, the regulatory complex of the 26S proteasome, interferes with α-synuclein assembly. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 4023–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.M.; Thulin, E.; Minogue, A.M.; Gustavsson, N.; Pang, E.; Teplow, D.B.; Linse, S. A facile method for expression and purification of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid β-peptide. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 1266–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udenfriend, S.; Stein, S.; Böhlen, P.; Dairman, W.; Leimgruber, W.; Weigele, M. Fluorescamine: A Reagent for Assay of Amino Acids, Peptides, Proteins, and Primary Amines in the Picomole Range. Science 1972, 178, 871–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barghorn, S.; Biernat, J.; Mandelkow, E. Purification of Recombinant Tau Protein and Preparation of Alzheimer-Paired Helical Filaments In Vitro. In Amyloid Proteins: Methods and Protocols; Sigurdsson, E.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, H., III. Thioflavine T interaction with synthetic Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid peptides: Detection of amyloid aggregation in solution. Protein Sci. 1993, 2, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-C.; Prusoff, W.H. A new rapid assay for measuring deoxycytidylate- and deoxythymidylate-kinase activities. Anal. Biochem. 1974, 60, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates; Elsevier/Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Routier, S.; Suzenet, F.; Chalon, S.; Buron, F.; Vercouillie, J.; Melki, R.; Boiaryna, L.; Guilloteau, D.; Pieri, L. Compounds for Using in Imaging and Particularly for the Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Patent WO2018055316, 29 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

| N° | Compound | Ki (nM) a | Kd (nM) b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Syn | Aβ | Tau | α-Syn | Aβ | Tau | ||

| 31 |  | >100 | 68.9 ± 30 | 19.6 ± 2 | ND | ND | ND |

| 32 |  | >100 | 37.9 ± 13 | 13.1 ± 2 | ND | ND | ND |

| 33 |  | 35.9 ± 5 | 3.3 ± 1 | 32.9 ± 8 | ND | ND | ND |

| 34 |  | 96.7 ± 14 | 68.9 ± 14 | 33.1 ± 7 | ND | ND | ND |

| 35 |  | 40.4 ± 6 | 26.2 ± 11 | 123 ± 28 | ND | ND | ND |

| 36 |  | >100 | 15.3 ± 7 | 7.2 ± 1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 37 |  | 47.8 ± 9 | 6.6 ± 2 | 17.2 ± 3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 38 |  | 36 ± 7 | 64.4 ± 40 | 27.6 ± 3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 39 |  | 21.7 ± 6 | 2.2 ± 1 | 12.7 ± 1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 40 |  | >100 | 10.1 ± 5 | 15.8 ± 3 | ND | ND | ND |

| 41 |  | 26 ± 16 | 21.3 ± 7 | 12.0 ± 1 | 3.25 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 2 | 0.13 ± 0.05 |

| 42 |  | 28.7 ± 8 | 91.5 ± 11 | 8.4 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 1 | 5.2 ± 3 | 0.49 ± 0.2 |

| 43 |  | 4.7 ± 2 | 24.4 ± 9 | 4.61 ± 0.2 | 0.53 ± 0.2 | 11.8 ± 3 | 0.44 ± 0.1 |

| 44 |  | 26.0 ± 16 | 21.3 ± 7 | 12.1 ± 1 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 2 | 2.4 ± 0.9 |

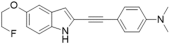

| 45 |  | ND | ND | ND | 2.4 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 1 | 0.97 ± 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boiaryna, L.; Pieri, L.; Chalon, S.; Serrière, S.; Bodard, S.; Chicheri, G.; Chenaf, E.; Suzenet, F.; Melki, R.; Buron, F.; et al. Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of the First 2-Alkynyl(aza)indole 18F Probe Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregates. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111638

Boiaryna L, Pieri L, Chalon S, Serrière S, Bodard S, Chicheri G, Chenaf E, Suzenet F, Melki R, Buron F, et al. Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of the First 2-Alkynyl(aza)indole 18F Probe Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregates. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111638

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoiaryna, Liliana, Laura Pieri, Sylvie Chalon, Sophie Serrière, Sylvie Bodard, Gabrielle Chicheri, Elisa Chenaf, Franck Suzenet, Ronald Melki, Frédéric Buron, and et al. 2025. "Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of the First 2-Alkynyl(aza)indole 18F Probe Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregates" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111638

APA StyleBoiaryna, L., Pieri, L., Chalon, S., Serrière, S., Bodard, S., Chicheri, G., Chenaf, E., Suzenet, F., Melki, R., Buron, F., Routier, S., & Vercouillie, J. (2025). Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of the First 2-Alkynyl(aza)indole 18F Probe Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregates. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111638