Abstract

Despite its prevalence and disease burden, several chasms still exist with regard to the pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder (BD). Polypharmacy is commonly encountered as a significant proportion of patients remain symptomatic, and the management of the depressive phase of the illness is a particular challenge. Gabapentin and pregabalin have often been prescribed off-label in spite of a paucity of evidence and clinical practice guidelines to support its use. This systematic review aimed to synthesize the available human clinical trials and inform evidence-based pharmacological approaches to BD management. A total of six randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) and 13 open-label trials involving the use of gabapentin and pregabalin in BD patients were reviewed. Overall, the studies show that gabapentin and its related drug pregabalin do not have significant clinical efficacy as either monotherapy or adjunctive therapy for BD. Gabapentin and pregabalin are probably ineffective for acute mania based on the findings of RCT, with only small open-label trials to support its potential adjunctive role. However, its effects on the long-term outcomes of BD remain to be elucidated. The evidence base was significantly limited by the generally small sample sizes and the trials also had heterogeneous designs and generally high risk of bias.

1. Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a debilitating mental illness that affects more than 1% of the world’s population [1]. Its lifetime prevalence in adults across 11 countries was estimated to be 0.4% [2]. In adolescents, the prevalence rate increases to 3–4% [2], making it one of the main causes of disability among youth [1]. In most patients, the onset of cognitive and psychosocial decline begins often at an age younger than 30 years [3] and is characterized by symptoms of depression and mania (bipolar I) or depression and hypomania (bipolar II) [1,3]. This predisposes the individual with BD to a significantly higher risk of death by suicide [4], an unfortunate clinical outcome that remains a challenging and pertinent issue [5]. It has also been suggested that sensory processes unique to individuals are implicated in their corresponding emotional patterns, making BD a very heterogenous condition [6].

The heavy socioeconomic burden associated with BD cannot be underestimated. Costs per capita ranged from USD 4000 to 5000 for direct mental healthcare and from USD 8000 to 14,000 for overall direct healthcare [7]. In the United States alone, the total costs of bipolar I disorder were approximately USD 200 billion in 2015 [8].

Therapeutic measures for BD are unfortunately limited by the incomplete remission of symptoms and frequent relapses. The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study reported recurrence rates of more than 50% and recovery rates of lower than 60% [9]. There is a glaring paucity of treatment options for bipolar depression and a clear need for effective acute and maintenance treatments for all individuals with BD, in order to delay illness progression, restore functioning and improve quality of life [10].

In modern clinical practice, patients generally are started on first-line BD medications and depending on symptom improvement and tolerability, either continued on the treatment regimen (with appropriate dose titration) or progressed to second-line medications. Alas, a combination of antipsychotics, mood stabilizers and other classes of psychotropic medications is often the choice in this challenging patient population, despite the inconsistent and scant evidence for polypharmacy [11].

With regard to pharmacotherapy, there has been sustained interest in the (off-label) use of gabapentin and its active metabolite, pregabalin in BD management. In patients with BD, the calcium pathway in intracellular secondary messaging of platelets is heightened [12], which suggests the involvement of calcium channels in BD pathophysiology. Pharmacodynamic evidence classifies gabapentin and pregabalin as ligands of the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels [13], and they have been reported to decrease neocortical noradrenaline release [14]. This inhibitory effect on calcium currents attenuates neurotransmitter release and subsequently reduces postsynaptic excitation [15]. While this mechanism of action has been reported in both rodent and human models, and across different pathological states (epilepsy, pain, anxiety) [14], evidence of efficacy for gabapentinoids in BD is still limited [16].

This systematic review hence endeavors to synthesize and elucidate all available evidence of gabapentin and pregabalin in the treatment of BD, thereby informing evidence-based pharmacological approaches to BD management.

2. Methods

This review protocol was guided by the latest Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [17]. A systematic search strategy employing different combinations of the keywords (bipolar, mania, hypomania, gabapentin, neurontin, gralise, gabarone, fanatrex, pregabalin, lyrica) was developed and performed in five databases namely OVID Medline, PubMed, ProQuest, PsychInfo and ScienceDirect from database inception to 7 June 2021. A search of gray literature was also employed to maximize identification of articles of interest. Abstracts were imported into Covidence (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) and screened by three independent researchers (Q.X.N., M.X.H., Y.L.L). Full-text articles were obtained for all abstracts of relevance and their respective reference lists hand-searched for references of interest. Forward searching of prospective citations of the relevant full texts was also performed and authors of the articles were contacted if necessary to provide additional data.

Full-text articles which were obtained for all relevant abstracts were reviewed by three researchers (Q.X.N., M.X.H., Y.L.L) for inclusion. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus. Studies were deemed eligible for inclusion based on the following criteria: (i) original published prospective clinical trial, (ii) patients were clinically diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Studies which were unpublished and not in English were excluded along with all case series, case reports, reviews, opinions and comments.

Data such as study design and population, clinical assessment tools, pharmacological interventions and key findings were extracted from all the studies reviewed and are summarized in Table 1. The quality and risk of bias of studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials [18], and graded based on the consensus of three study investigators (Q.X.N., M.X.H., Y.L.L.).

Table 1.

Studies reviewed (arranged alphabetically by first author’s last name).

3. Results

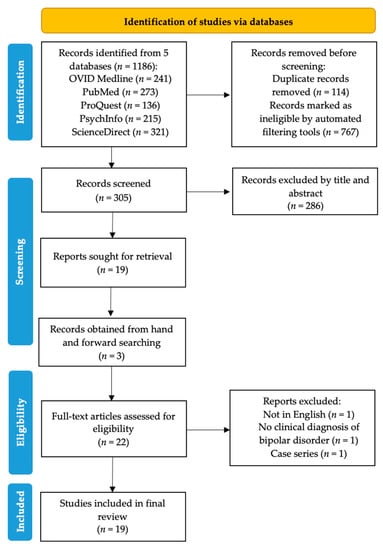

Figure 1 detailed the study selection and identification process. A total of 1186 records were found from the database search, with 767 records marked ineligible by automated filters and 114 records removed as duplicates. A total of 286 articles were further excluded after title and abstract screening, and subsequently three articles were excluded after a full text review. Finally, a total of 19 studies were included for thematic analysis [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing the abstraction process.

There were 18 studies that trialled gabapentin use in BD [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,33,34] and only one study on pregabalin [29]. With reference to Table 1, study designs were heterogenous with a total of 13 open-label trials [19,21,22,23,25,26,30,31,32,33,34,36,37] and six RCTs, which employed different treatment regimes from cross-over trials to fixed-dose trials. [20,24,27,28,29,35] Most of these trials had a generally high risk of bias, as seen in Table 2. Due to this heterogeneity in designs, it was challenging to discern the source of the therapeutic effect, making it difficult to attribute any observed benefit to solely gabapentin or pregabalin. A meta-analysis was not performed for these reasons.

Table 2.

Results of Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias.

3.1. Intervention Type

Most of the studies were adjunctive treatment trials: 12 of the included studies administered gabapentin as an adjunctive treatment [16,17,18,19,23,27,28,30,31,32,33,34]. One study administered pregabalin as an adjunctive treatment [29]. Three studies administered gabapentin as a monotherapy [20,22,26] and another two studies employed a cross-over design with lamotrigine and placebo with a one-week washout period in between treatment segments [21,25]. Only one study administered gabapentin both as an add-on treatment and a monotherapy and compared the differences between these two experimental arms [20].

3.2. Dosing Regimes

The most common range of gabapentin dosing was 300 to 2400 mg/day. The maximum daily dose was 4800 mg. It was reported by Sokolski et al. that most patients had attained therapeutic effectiveness at a 900 mg dose even though the initial dose was 300 mg [33]. For the sole study on pregabalin, the average dose for acute patients was 72 mg/day [29].

3.3. Clinical Assessment Tools

There was a wide spectrum of scales used to assess symptom severity and treatment response across all 19 studies. With respect to the assessment of mania, ten studies utilized the YMRS, three studies utilized the BMRS while another three studies used the HAM-A. The Clinical Global Impression Scale for use in Bipolar Illness (CGI-BP) was used in five studies while the CGI-S and CGI-C subscales were used in two and three studies respectively. The BPRS was used in three studies, while the STAI was used in two studies. The AIRP, MMPI-2, SADS and ISS were each employed by one study.

3.4. Treatment Efficacy and Side Effects

Five studies reported a significant reduction in severity scores for mania post gabapentin therapy [20,23,27,29,33]. Among these five trials, it was Pande et al.’s 2000 study that reported a lower decrease in YMRS scores for the gabapentin experimental arm as compared to the placebo arm [29].

Seven studies reported a significant reduction in severity scores for depression, with gabapentin therapy. Four studies reported significant improvement in bipolar severity as measured by BPRS, AIRP and CGI-BP. Sedation was the most common side effect as reported in six studies [19,21,23,26,33,36].

Of note is the difference in treatment efficacy noted by Erfurth et al.’s 1998 study that compared adjunctive gabapentin treatment with gabapentin monotherapy within the same time period [20]. For the adjunctive group, all six patients had a significant decrease in their BMRS scores, while for the monotherapy group, four out of eight patients dropped out due to treatment insufficiency. There was a significant decrease in BMRS scores for the remaining four patients in the monotherapy group.

4. Discussion

Overall, the studies show that gabapentin and its related drug pregabalin do not have significant clinical efficacy as either monotherapy or adjunctive therapy for patients with BD. Multiple RCTs have found that gabapentin and pregabalin are ineffective for acute mania, with only small open-label trials to support its potential adjunctive role. There may be an adjunctive role for patients in a depressed state or with comorbid anxiety or substance use issues.

As most studies were adjunctive treatment trials, it remains unclear if the positive therapeutic response observed was primarily the result of the drug that was added to pre-existing agents (usually stable doses of mood stabilizers or antipsychotics), or the result of a synergistic effect. Furthermore, in open trials, without appropriate controls, it is also unclear if the observed effect is due to spontaneous remission of symptoms given the natural history of BD. While crossover trial designs have a key drawback of carryover effects although these tend to be reduced with a washout period that lasts a week or two between treatment segments [38].

The existence of a single trial that investigated the use of pregabalin in BD limits any strong conclusions. Pregabalin was developed as a successor to gabapentin; it was formally approved in 2004, as compared to gabapentin, which has been in use since 1994 [39]. The pharmacodynamic action of pregabalin is similar to gabapentin, characterized by its binding to the α2-δ subunit on voltage-gated calcium channels. Pregabalin is structurally similar to the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) although it does not bind to GABA receptors nor does it impact the uptake or breakdown of GABA. While various pharmacologic effects have been reported, pregabalin essentially acts to reduce the release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as substance P and glutamate, which have been linked to the pathogenesis of bipolar disorders.

Gabapentin and pregabalin are probably not effective for depressive state but may improve some subscales, such as irritability, social withdrawal or anxiety. They may have benefits for anxiety symptoms as do most GABAergic agents and also potential utility for bipolar individuals with comorbid substance use disorders. Its sedating effects probably can help alleviate insomnia and it is generally well-tolerated in terms of side-effect profile.

Bipolar illness is a life-course disorder; its chronic, enduring nature with interspersed periods of elation, irritability and depression usually demands maintenance treatment [10]. It was interesting to note that in an open-label trial, 39.5% (n = 17) of the patients maintained symptomatic remission over a period of 4 to 18 months on adjunctive gabapentin [28]. However, as therapeutic strategies shift towards long-term horizons, there are increasing concerns regarding dependence with long-term use. Relative to lithium, the use of gabapentin is significantly associated with a doubling of the risk of suicidality in patients diagnosed with BD [40].

Potential issues with dependence and also elevated mood switch belie the use of gabapentinoids. Even though gabapentin and pregabalin are considered as a treatment option for alcohol and substance abuse, there are numerous published case reports and case series documenting abuse, dependence, and withdrawal effects [41]. Caution must also be exercised by monitoring renal function due to the excretion of these drugs via renal pathways.

Another limitation of current evidence pertains to the different clinical assessment tools used to evaluate BD symptom severity and treatment response. BD is in itself a complex disorder, presenting with heterogeneous symptoms ranging from depression, hypomania to mixed states and even psychosis [42]. Many rating tools have been used in the clinical assessment of BD patients; however, they all have certain weaknesses [43]. For example, the usual CGI is a global measure of improvement in functioning, without rating scales specific for hypomanic/manic and depressive symptoms, compared to the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), the Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale (BMRS) [44], or the modified CGI-BP [45]. When studying patients with rapid-cycling states, multiple scales should be used to more adequately evaluate response [24]. Importantly, the contemporary redefinition of the clinical hallmarks of bipolar disorder (with activation as the most common dimension in mania), also necessitates the revisiting of new scales that apportion greater emphasis to activity or energy levels in this patient population [46,47].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, there is a lack of rigorous evidence to support the clinical efficacy of gabapentin and pregabalin for the treatment of acute mania or acutely depressed BD patients. It should not be used as monotherapy in the short- or long-term period, however, as adjunctive therapy, its effects on the long-term outcomes of BD remain to be elucidated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.X.N. and K.T.C.; Data Curation, M.X.H., S.E.T., C.Y.L.Y. and Y.L.L.; Formal Analysis, Q.X.N., M.X.H., S.E.T., C.Y.L.Y. and Y.L.L.; Investigation, Q.X.N., Y.L.L. and K.T.C.; Methodology, Q.X.N., M.X.H., S.E.T., C.Y.L.Y., Y.L.L. and K.T.C.; Resources, Q.X.N.; Software, Q.X.N. and M.X.H.; Supervision, K.T.C.; Writing—Original Draft, Q.X.N., M.X.H., S.E.T., C.Y.L.Y., Y.L.L. and K.T.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, Q.X.N., M.X.H., S.E.T., C.Y.L.Y., Y.L.L. and K.T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grande, I.; Berk, M.; Birmaher, B.; Vieta, E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet 2016, 387, 1561–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Lamers, F. The ‘true’prevalence of bipolar II disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2012, 25, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benazzi, F. Bipolar disorder—Focus on bipolar II disorder and mixed depression. Lancet 2007, 369, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, A.; Isometsä, E.T.; Tondo, L.; Doris, H.M.; Turecki, G.; Reis, C.; Cassidy, F.; Sinyor, M.; Azorin, J.M.; Kessing, L.V. International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide: Meta-analyses and meta-regression of correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Muñoz, F.; Shen, W.W.; D’ocon, P.; Romero, A.; Álamo, C. A history of the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serafini, G.; Gonda, X.; Pompili, M.; Rihmer, Z.; Amore, M.; Engel-Yeger, B. The relationship between sensory processing patterns, alexithymia, traumatic childhood experiences, and quality of life among patients with unipolar and bipolar disorders. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 62, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleine-Budde, K.; Touil, E.; Moock, J.; Bramesfeld, A.; Kawohl, W.; Rössler, W. Cost of illness for bipolar disorder: A systematic review of the economic burden. Bipolar Disord. 2014, 16, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, M.; Greene, M.; Guerin, A.; Touya, M.; Wu, E. The economic burden of bipolar I disorder in the United States in 2015. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlis, R.H.; Ostacher, M.J.; Patel, J.K.; Marangell, L.B.; Zhang, H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Ketter, T.A.; Miklowitz, D.J.; Otto, M.W.; Gyulai, L. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: Primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatham, L.N.; Kennedy, S.H.; Parikh, S.V.; Schaffer, A.; Bond, D.J.; Frey, B.N.; Sharma, V.; Goldstein, B.I.; Rej, S.; Beaulieu, S. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018, 20, 97–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerio, A.; Russo, D.; Miletto, N.; Aguglia, A.; Costanza, A.; Benatti, B.; Odone, A.; Barroilhet, S.A.; Brakoulias, V.; Dell’Osso, B. Polypharmacy as maintenance treatment in bipolar illness: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, S.; Kagaya, A.; Tawara, Y.; Inagaki, M. Intracellular calcium signaling systems in the pathophysiology of affective disorders. Life Sci. 1998, 62, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, N.S.; Brown, J.P.; Dissanayake, V.U.; Offord, J.; Thurlow, R.; Woodruff, G.N. The novel anticonvulsant drug, gabapentin (Neurontin), binds to the subunit of a calcium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 5768–5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dooley, D.J.; Donovan, C.M.; Meder, W.P.; Whetzel, S.Z. Preferential action of gabapentin and pregabalin at P/Q-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels: Inhibition of K+-evoked [3H]-norepinephrine release from rat neocortical slices. Synapse 2002, 45, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sills, G.J. The mechanisms of action of gabapentin and pregabalin. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, K.T.; Forrest, A.; Awad, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Stockton, S.; Harrison, P.J.; Geddes, J.R.; Cipriani, A. Biological rationale and potential clinical use of gabapentin and pregabalin in bipolar disorder, insomnia and anxiety: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Altshuler, L.L.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; McElroy, S.L.; Suppes, T.; Brown, E.S.; Denicoff, K.; Frye, M.; Gitlin, M.; Hwang, S.; Goodman, R.; et al. Gabapentin in the acute treatment of refractory bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 1999, 1, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astaneh, A.N.; Rezaei, O. Adjunctive treatment with gabapentin in bipolar patients during acute mania. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2012, 43, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabras, P.L.; Hardoy, J.; Hardoy, M.C.; Carta, M.G. Clinical experience with gabapentin in patients with bipolar or schizoaffective disorder: Results of an open-label study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, M.G.; Hardoy, M.C.; Dessi, I.; Hardoy, M.J.; Carpiniello, B. Adjunctive gabapentin in patients with intellectual disability and bipolar spectrum disorders. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2001, 45, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfurth, A.; Kammerer, C.; Grunze, H.; Normann, C.; Walden, J. An open label study of gabapentin in the treatment of acute mania. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1998, 32, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, M.A.; Ketter, T.A.; Kimbrell, T.A.; Dunn, R.T.; Speer, A.M.; Osuch, E.A.; Luckenbaugh, D.A.; Cora-Ocatelli, G.; Leverich, G.S.; Post, R.M. A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2000, 20, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, M.C.; Laini, V.; Scalvini, M.E.; Omboni, A.; Ferrari, V.M.; Clemente, A.; Salvi, V.; Cerveri, G. Gabapentin and the prophylaxis of bipolar disorders in patients intolerant to lithium. Clin. Drug Investig. 2001, 21, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, S.L.; Soutullo, C.A.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Kmetz, G.F. A pilot trial of adjunctive gabapentin in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 1997, 9, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhber, N.; Lane, C.J.; Azarpazhooh, M.R.; Salari, E.; Fayazi, R.; Shakeri, M.T.; Young, A.H. Anticonvulsant treatments of dysphoric mania: A trial of gabapentin, lamotrigine and carbamazepine in Iran. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Obrocea, G.V.; Dunn, R.M.; Frye, M.A.; Ketter, T.A.; Luckenbaugh, D.A.; Leverich, G.S.; Speer, A.M.; Osuch, E.A.; Jajodia, K.; Post, R.M. Clinical predictors of response to lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory affective disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 51, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, A.C.; Crockatt, J.G.; Janney, C.A.; Werth, J.L.; Tsaroucha, G. Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: A placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy. Gabapentin Bipolar Disorder Study Group. Bipolar Disord. 2000, 2, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Toni, C.; Frare, F.; Ruffolo, G.; Moretti, L.; Torti, C.; Akiskal, H.S. Effectiveness of adjunctive gabapentin in resistant bipolar disorder: Is it due to anxious-alcohol abuse comorbidity? J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002, 22, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Toni, C.; Ruffolo, G.; Sartini, S.; Simonini, E.; Akiskal, H. Clinical experience using adjunctive gabapentin in treatment-resistant bipolar mixed states. Pharmacopsychiatry 1999, 32, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schaffer, L.C.; Schaffer, C.B.; Miller, A.R.; Manley, J.L.; Piekut, J.A.; Nordahl, T.E. An open trial of pregabalin as an acute and maintenance adjunctive treatment for outpatients with treatment resistant bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 147, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolski, K.N.; Green, C.; Maris, D.E.; DeMet, E.M. Gabapentin as an adjunct to standard mood stabilizers in outpatients with mixed bipolar symptomatology. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Acad. Clin. Psychiatr. 1999, 11, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieta, E.; Martinez-Aran, A.; Nieto, E.; Colom, F.; Reinares, M.; Benabarre, A.; Gasto, C. Adjunctive gabapentin treatment of bipolar disorder. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2000, 15, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieta, E.; Manuel Goikolea, J.; Martínez-Arán, A.; Comes, M.; Verger, K.; Masramon, X.; Sanchez-Moreno, J.; Colom, F. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of adjunctive gabapentin for bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 67, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.W.; Santosa, C.; Schumacher, M.; Winsberg, M.E.; Strong, C.; Ketter, T.A. Gabapentin augmentation therapy in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2002, 4, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.T.; Robb, J.C.; Hasey, G.M.; MacQueen, G.M.; Siotis, I.P.; Marriott, M.; Joffe, R.T. Gabapentin as an adjunctive treatment in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 1999, 55, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, R.M.; Luckenbaugh, D.A. Unique design issues in clinical trials of patients with bipolar affective disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2003, 37, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driot, D.; Jouanjus, E.; Oustric, S.; Dupouy, J.; Lapeyre-Mestre, M. Patterns of gabapentin and pregabalin use and misuse: Results of a population-based cohort study in France. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leith, W.M.; Lambert, W.E.; Boehnlein, J.K.; Freeman, M.D. The association between gabapentin and suicidality in bipolar patients. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 34, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersfelder, T.L.; Nichols, W.H. Gabapentin: Abuse, dependence, and withdrawal. Ann. Pharmacother. 2016, 50, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Q.X.; Lim, D.Y.; Chee, K.T. Reimagining the spectrum of affective disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2020, 22, 638–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picardi, A. Rating scales in bipolar disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2009, 22, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.J.; Johnson, S.L.; Eisner, L. Assessment tools for adult bipolar disorder. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2009, 16, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spearing, M.K.; Post, R.M.; Leverich, G.S.; Brandt, D.; Nolen, W. Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): The CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res. 1997, 73, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Murray, G.; Henry, C.; Morken, G.; Scott, E.; Angst, J.; Merikangas, K.R.; Hickie, I.B. Activation in bipolar disorders: A systematic review. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.; Murray, G. Are rating scales for bipolar disorders fit for purpose? Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).