Therapeutic Single Compounds for Osteoarthritis Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. OA Clinical Treatment

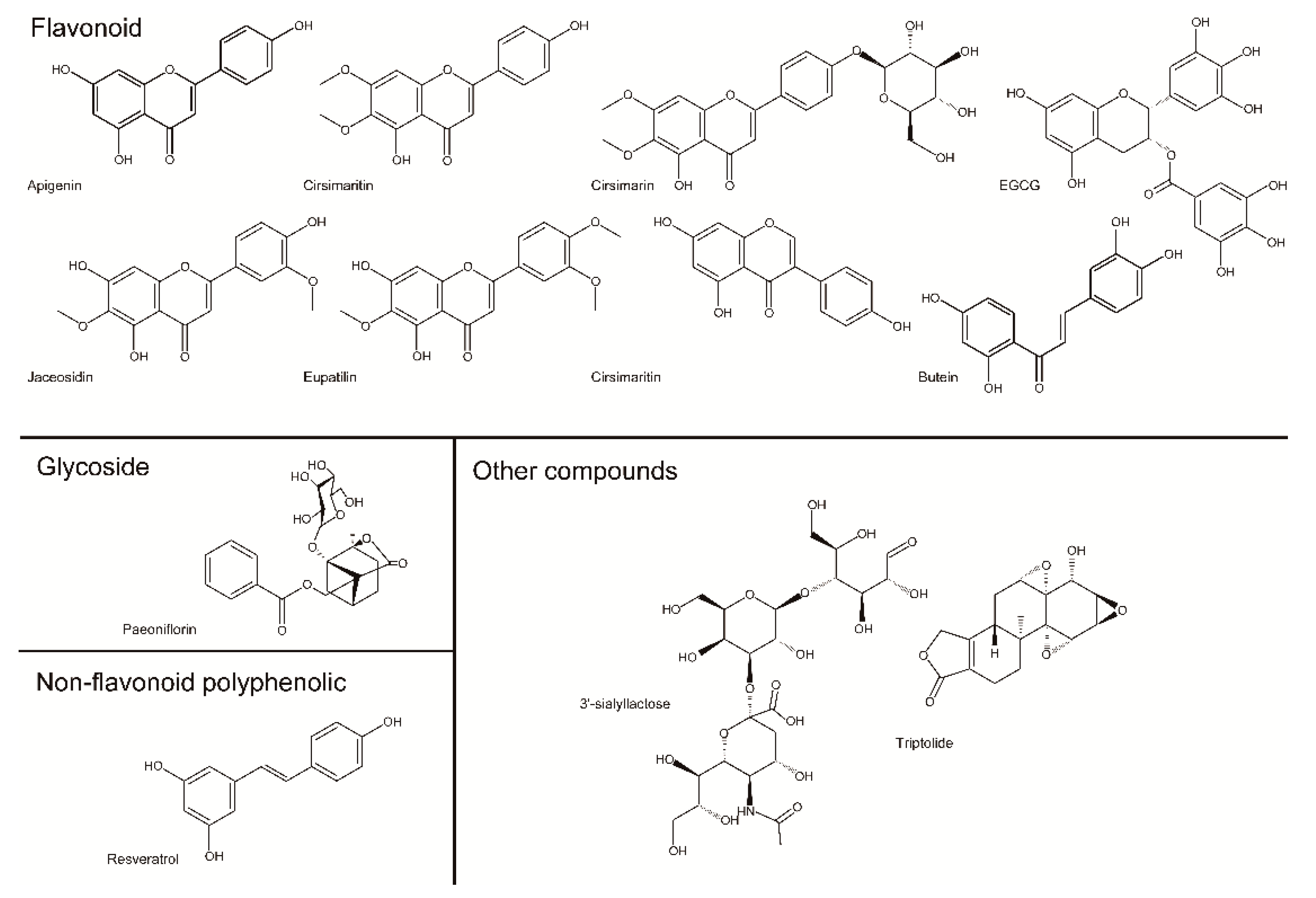

2. Candidate Therapeutic Agents

2.1. Mixture Compounds

2.1.1. Cirsium japonicum var. maackii

2.1.2. Seomae Mugwort

2.1.3. Capparis spinosa L.

2.2. Single Compounds

2.2.1. Flavonoids

Apigenin

Cirsimarin and Cirsimaritin

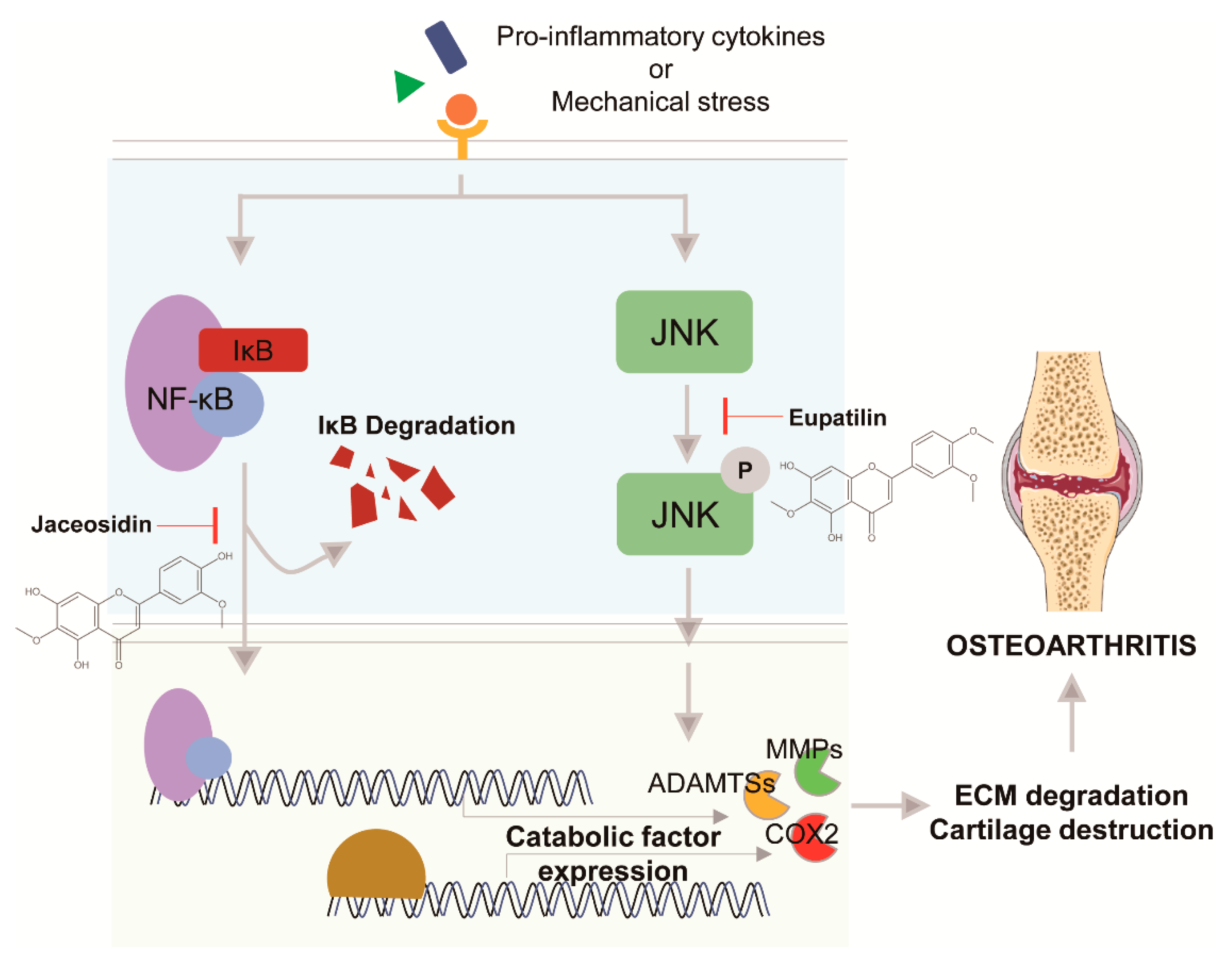

Jaceosidin

Eupatilin

Genistein

Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG)

Butein

Wogonin

Morin

Quercetin

2.2.2. Glycosides

Paeoniflorin

Clematis Saponins

2.2.3. Non-Flavonoid Polyphenolics

Resveratrol

Curcumin

2.2.4. Other Compounds

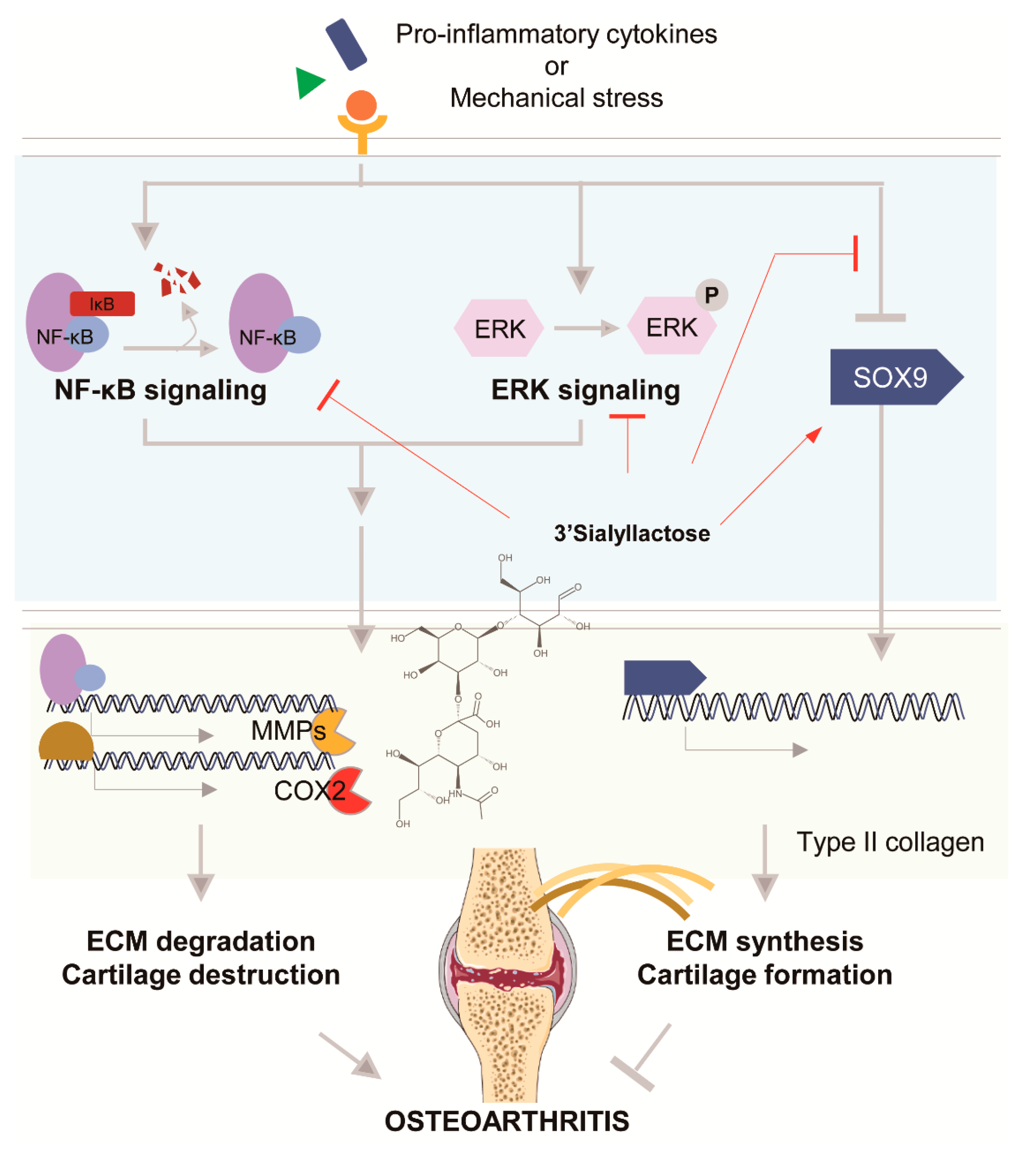

3′-Sialyllactose

Triptolide (Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f.)

Hyaluronic Acid (HA)

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felson, D.T.; Lawrence, R.C.; Dieppe, P.A.; Hirsch, R.; Helmick, C.G.; Jordan, J.M.; Kington, R.S.; Lane, N.E.; Nevitt, M.C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Osteoarthritis: New insights. Part 1: The disease and its risk factors. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieppe, P.A.; Lohmander, L.S. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet 2005, 365, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, I.; Tsuji, K.; Koopman, P.; Watanabe, H.; Yamada, Y.; Shinomiya, K.; Nifuji, A.; Noda, M. SOX9 enhances aggrecan gene promoter/enhancer activity and is up-regulated by retinoic acid in a cartilage-derived cell line, TC6. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 10738–10744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, N.; Khan, N.M.; Ashruf, O.S.; Haqqi, T.M. Inhibition of cartilage degradation and suppression of PGE(2) and MMPs expression by pomegranate fruit extract in a model of posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Nutrition 2017, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosang, A.J.; Last, K.; Knäuper, V.; Murphy, G.; Neame, P.J. Degradation of cartilage aggrecan by collagenase-3 (MMP-13). FEBS Lett. 1996, 380, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jordan, J.M. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2010, 26, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, K.E.; Helmick, C.G.; Boring, M.; Brady, T.J. Vital Signs: Prevalence of Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis and Arthritis-Attributable Activity Limitation—United States, 2013–2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barten, D.J.; Swinkels, L.C.; Dorsman, S.A.; Dekker, J.; Veenhof, C.; de Bakker, D.H. Treatment of hip/knee osteoarthritis in Dutch general practice and physical therapy practice: An observational study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverwood, V.; Blagojevic-Bucknall, M.; Jinks, C.; Jordan, J.L.; Protheroe, J.; Jordan, K.P. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, B.R.; Katz, J.N.; Solomon, D.H.; Yelin, E.H.; Hunter, D.J.; Messier, S.P.; Suter, L.G.; Losina, E. Number of Persons With Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis in the US: Impact of Race and Ethnicity, Age, Sex, and Obesity. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrotin, Y.; Mobasheri, A. Natural Products for Promoting Joint Health and Managing Osteoarthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2018, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.H.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, C.J.; Park, J.S. Natural Products as Sources of Novel Drug Candidates for the Pharmacological Management of Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Biomol. Ther. 2019, 27, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.W.; Chang, J.C.; Lin, L.W.; Tsai, F.H.; Chang, H.C.; Wu, C.R. Comparison of the Hepatoprotective Effects of Four Endemic Cirsium Species Extracts from Taiwan on CCl4-Induced Acute Liver Damage in C57BL/6 Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Shao, H.; Chen, Y.; Ding, N.; Yang, A.; Tian, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y. In renal hypertension, Cirsium japonicum strengthens cardiac function via the intermedin/nitric oxide pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kang, S.H.; Ghil, S.H. Cirsium japonicum extract induces apoptosis and anti-proliferation in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Mol. Med. Rep. 2010, 3, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.A.; Abdul, Q.A.; Byun, J.S.; Joung, E.J.; Gwon, W.G.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, H.R.; Choi, J.S. Protective effects of flavonoids isolated from Korean milk thistle Cirsium japonicum var. maackii (Maxim.) Matsum on tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced hepatotoxicity in HepG2 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 209, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Lee, S.J.; Venkatarame Gowda Saralamma, V.; Ha, S.E.; Vetrivel, P.; Desta, K.T.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Shin, S.C.; Kim, G.S. Polyphenol mixture of a native Korean variety of Artemisia argyi H. (Seomae mugwort) and its anti-inflammatory effects. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.S.; Shin, J.S.; Lee, S.B.; Park, J.C.; Lee, K.T. Cirsimarin, a flavone glucoside from the aerial part of Cirsium japonicum var. ussuriense (Regel) Kitam. ex Ohwi, suppresses the JAK/STAT and IRF-3 signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 293, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, A.; Seong, S.H.; Shrestha, S.; Jung, H.A.; Choi, J.S. Korean Thistle (Cirsium japonicum var. maackii (Maxim.) Matsum.): A Potential Dietary Supplement against Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2019, 24, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.; Kang, L.J.; Jang, D.; Jeon, J.; Lee, H.; Choi, S.; Han, S.J.; Oh, E.; Nam, J.; Kim, C.S.; et al. Cirsium japonicum var. maackii and apigenin block Hif-2α-induced osteoarthritic cartilage destruction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 5369–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Jang, D.; Jeon, J.; Cho, C.; Choi, S.; Han, S.J.; Oh, E.; Nam, J.; Park, C.H.; Shin, Y.S.; et al. Seomae mugwort and jaceosidin attenuate osteoarthritic cartilage damage by blocking IκB degradation in mice. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 8126–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Grimalt, M.; Legua, P.; Almansa, M.S.; Amorós, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Hernández, F. Polyphenol Compounds and Biological Activity of Caper (Capparis spinosa L.) Flowers Buds. Plants 2019, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panico, A.M.; Cardile, V.; Garufi, F.; Puglia, C.; Bonina, F.; Ronsisvalle, G. Protective effect of Capparis spinosa on chondrocytes. Life Sci. 2005, 77, 2479–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresca, M.; Micheli, L.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Tenci, B.; Innocenti, M.; Khatib, M.; Mulinacci, N.; Ghelardini, C. Acute effect of Capparis spinosa root extracts on rat articular pain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 193, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.; Kar, A. Apigenin (4’,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) regulates hyperglycaemia, thyroid dysfunction and lipid peroxidation in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danciu, C.; Zupko, I.; Bor, A.; Schwiebs, A.; Radeke, H.; Hancianu, M.; Cioanca, O.; Alexa, E.; Oprean, C.; Bojin, F.; et al. Botanical Therapeutics: Phytochemical Screening and Biological Assessment of Chamomile, Parsley and Celery Extracts against A375 Human Melanoma and Dendritic Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Yadav, D.K.; Siripurapu, K.B.; Palit, G.; Maurya, R. Constituents of Ocimum sanctum with antistress activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 1410–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, G.; Ozcan, M.M. Some phenolic compounds of extracts obtained from Origanum species growing in Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 4947–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Suchal, K.; Khan, S.I.; Bhatia, J.; Kishore, K.; Dinda, A.K.; Arya, D.S. Apigenin ameliorates streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats via MAPK-NF-κB-TNF-α and TGF-β1-MAPK-fibronectin pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2017, 313, F414–F422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazarolli, L.H.; Folador, P.; Moresco, H.H.; Brighente, I.M.; Pizzolatti, M.G.; Silva, F.R. Mechanism of action of the stimulatory effect of apigenin-6-C-(2”-O-alpha-l-rhamnopyranosyl)-beta-L-fucopyranoside on 14C-glucose uptake. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 179, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kim, D.K.; Shin, H.D.; Lee, H.J.; Jo, H.S.; Jeong, J.H.; Choi, Y.L.; Lee, C.J.; Hwang, S.C. Apigenin Regulates Interleukin-1β-Induced Production of Matrix Metalloproteinase Both in the Knee Joint of Rat and in Primary Cultured Articular Chondrocytes. Biomol. Ther. 2016, 24, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantowi, N.; Mohamed, S.; Lau, S.F.; Hussin, P. Comparison of diclofenac with apigenin-glycosides rich Clinacanthus nutans extract for amending inflammation and catabolic protease regulations in osteoporotic-osteoarthritis rat model. Daru 2020, 28, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasrat, J.A.; Pieters, L.; Claeys, M.; Vlietinck, A.; De Backer, J.P.; Vauquelin, G. Adenosine-1 active ligands: Cirsimarin, a flavone glycoside from Microtea debilis. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, B.; Ahmed, A.; Sarwar, R.; Khan, A.; Farooq, U.; Abid Ali, S.; Al-Harrasi, A. Apoptotic and antimetastatic activities of betulin isolated from Quercus incana against non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 1667–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrouki, B.; Pillon, N.J.; Kalbacher, E.; Soula, H.A.; Nia N’Jomen, G.; Grand, L.; Chambert, S.; Geloen, A.; Soulage, C.O. Cirsimarin, a potent antilipogenic flavonoid, decreases fat deposition in mice intra-abdominal adipose tissue. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, J.; Hwang, G.S.; Lee, H.L.; Hahm, D.H.; Huh, C.K.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, S.; Kang, K.S. Protective effect of cirsimaritin against streptozotocin-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, G.; Singh, S.; Kumari, P.; Raza, W.; Hussain, Y.; Meena, A. Cirsimaritin, a lung squamous carcinoma cells (NCIH-520) proliferation inhibitor. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Ma, X.; Yin, J.; Wu, S.; Huang, H.; Li, Y. Cirsimaritin inhibits influenza A virus replication by downregulating the NF-κB signal transduction pathway. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Jena, L.; Mohod, K.; Daf, S.; Varma, A.K. Virtual screening for potential inhibitors of high-risk human papillomavirus 16 E6 protein. Interdiscip. Sci. 2015, 7, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Han, J.M.; Jin, Y.Y.; Baek, N.I.; Bang, M.H.; Chung, H.G.; Choi, M.S.; Lee, K.T.; Sok, D.E.; Jeong, T.S. In vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Jaceosidin from Artemisia princeps Pampanini cv. Sajabal. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008, 31, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.L.; Wei, X.C.; Guo, L.Q.; Zhao, L.; Chen, X.H.; Cui, Y.D.; Yuan, J.; Chen, D.F.; Zhang, J. The therapeutic effects of Jaceosidin on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 140, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Hong, K.; Kwon, B.M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.H. Jaceosidin Ameliorates Insulin Resistance and Kidney Dysfunction by Enhancing Insulin Receptor Signaling and the Antioxidant Defense System in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Wu, Z.; Chen, N.; Zhong, K.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wan, P.; Lu, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, S. Eupatilin Inhibits Renal Cancer Growth by Downregulating MicroRNA-21 through the Activation of YAP1. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5016483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.H.; Chung, K.S.; Kang, Y.M.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, M.; An, H.J. Eupatilin suppresses the allergic inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine 2018, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Moon, S.J.; Jhun, J.Y.; Yang, E.J.; Cho, M.L.; Min, J.K. Eupatilin Exerts Antinociceptive and Chondroprotective Properties in a Rat Model of Osteoarthritis by Downregulating Oxidative Damage and Catabolic Activity in Chondrocytes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Y.; Wu, J.; Liang, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Guo, X. Eupatilin protects chondrocytes from apoptosis via activating sestrin2-dependent autophagy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 75, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukund, V.; Saddala, M.S.; Farran, B.; Mannavarapu, M.; Alam, A.; Nagaraju, G.P. Molecular docking studies of angiogenesis target protein HIF-1α and genistein in breast cancer. Gene 2019, 701, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.H.; Huang, S.Y.; Kung, C.W.; Chen, S.Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Cheng, P.Y.; Lam, K.K.; Lee, Y.M. Genistein ameliorated obesity accompanied with adipose tissue browning and attenuation of hepatic lipogenesis in ovariectomized rats with high-fat diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 67, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guo, P.; Huang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Hu, J. Anti-chondrocyte apoptosis effect of genistein in treating inflammation-induced osteoarthritis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 2032–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.C.; Wang, C.C.; Lu, J.W.; Lee, C.H.; Chen, S.C.; Ho, Y.J.; Peng, Y.J. Chondroprotective Effects of Genistein against Osteoarthritis Induced Joint Inflammation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephart, E.D.; Setchell, K.D.; Lund, T.D. Phytoestrogens: Hormonal action and brain plasticity. Brain Res. Bull. 2005, 65, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, H.; Briese, V.; Manapov, F.; Nebe, B.; Schünke, M.; Kurz, B. The phytoestrogens daidzein and genistein enhance the insulin-stimulated sulfate uptake in articular chondrocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 2008, 333, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colina, J.R.; Suwalsky, M.; Manrique-Moreno, M.; Petit, K.; Aguilar, L.F.; Jemiola-Rzeminska, M.; Strzalka, K. Protective effect of epigallocatechin gallate on human erythrocytes. Colloids Surf. Biointerfaces 2019, 173, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Ahmed, S.; Islam, N.; Goldberg, V.M.; Haqqi, T.M. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced expression of nitric oxide synthase and production of nitric oxide in human chondrocytes: Suppression of nuclear factor kappaB activation by degradation of the inhibitor of nuclear factor kappaB. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 2079–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Wang, N.; Lalonde, M.; Goldberg, V.M.; Haqqi, T.M. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) differentially inhibits interleukin-1 beta-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -13 in human chondrocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, Z.; Rasheed, N.; Al-Shaya, O. Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate modulates global microRNA expression in interleukin-1β-stimulated human osteoarthritis chondrocytes: Potential role of EGCG on negative co-regulation of microRNA-140-3p and ADAMTS5. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xiao, L.; Yu, C.; Jin, P.; Qin, D.; Xu, Y.; Yin, J.; Liu, Z.; Du, Q. Enhanced Antiarthritic Efficacy by Nanoparticles of (-)-Epigallocatechin Gallate-Glucosamine-Casein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 6476–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, F.; Scanu, A.; Zamudio-Cuevas, Y.; Punzi, L.; Spinella, P. Anti-inflammatory effects of polyphenols in arthritis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, L.; Feng, Z.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y. Butein inhibits IL-1β-induced inflammatory response in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes and slows the progression of osteoarthritis in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.Y.; Ahmad, N.; Haqqi, T.M. Butein Activates Autophagy Through AMPK/TSC2/ULK1/mTOR Pathway to Inhibit IL-6 Expression in IL-1β Stimulated Human Chondrocytes. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 49, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, C.C.; Mao, M.; Yuan, J.F.; Peng, S.T.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, N.; Wei, J.; Li, X.X.; Zhang, K.; Li, F. Correlation between color of Scutellariae Radix pieces and content of five flavonoids after softening and cutting by different methods. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2019, 44, 4467–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Lin, G.; Zuo, Z. Pharmacological effects and pharmacokinetics properties of Radix Scutellariae and its bioactive flavones. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2011, 32, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.M.; Haseeb, A.; Ansari, M.Y.; Haqqi, T.M. A wogonin-rich-fraction of Scutellaria baicalensis root extract exerts chondroprotective effects by suppressing IL-1β-induced activation of AP-1 in human OA chondrocytes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, A.; Cirri, P.; Santi, A.; Paoli, P. Morin: A Promising Natural Drug. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 774–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, N.; Gao, C.; Liu, F. Morin Exhibits Anti-Inflammatory Effects on IL-1β-Stimulated Human Osteoarthritis Chondrocytes by Activating the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 51, 1830–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.J.; Cho, I.A.; Oh, J.S.; Seo, Y.S.; You, J.S.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, J.S. Anticatabolic Effects of Morin through the Counteraction of Interleukin-1β-Induced Inflammation in Rat Primary Chondrocytes. Cells Tissues Organs 2019, 207, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.P.; Hu, P.F.; Bao, J.P.; Wu, L.D. Morin exerts antiosteoarthritic properties: An in vitro and in vivo study. Exp. Biol. Med. 2012, 237, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.K.; Chin, K.Y.; Ima-Nirwana, S. Quercetin as an Agent for Protecting the Bone: A Review of the Current Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyva-López, N.; Gutierrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Ambriz-Perez, D.L.; Heredia, J.B. Flavonoids as Cytokine Modulators: A Possible Therapy for Inflammation-Related Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzaki, N.; Saito, K.; Maeda, A.; Kitagawa, Y.; Kiso, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Tomonaga, A.; Nagaoka, I.; Yamaguchi, H. Effect of a dietary supplement containing glucosamine hydrochloride, chondroitin sulfate and quercetin glycosides on symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Sylvester, J.; Ahmad, M.; Zafarullah, M. Involvement of H-Ras and reactive oxygen species in proinflammatory cytokine-induced matrix metalloproteinase-13 expression in human articular chondrocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 507, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britti, D.; Crupi, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Gugliandolo, E.; Fusco, R.; Schievano, C.; Morittu, V.M.; Evangelista, M.; Di Paola, R.; Cuzzocrea, S. A novel composite formulation of palmitoylethanolamide and quercetin decreases inflammation and relieves pain in inflammatory and osteoarthritic pain models. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleagrahara, N.; Hodgson, K.; Miranda-Hernandez, S.; Hughes, S.; Kulur, A.B.; Ketheesan, N. Flavonoid quercetin-methotrexate combination inhibits inflammatory mediators and matrix metalloproteinase expression, providing protection to joints in collagen-induced arthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2018, 26, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, K.; Chen, Z.; Pengcheng, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X. Quercetin attenuates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis via SIRT1/AMPK-mediated inhibition of ER stress in rat chondrocytes and prevents the progression of osteoarthritis in a rat model. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 18192–18205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strugała, P.; Tronina, T.; Huszcza, E.; Gabrielska, J. Bioactivity In Vitro of Quercetin Glycoside Obtained in Beauveria bassiana Culture and Its Interaction with Liposome Membranes. Molecules 2017, 22, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivappagowdar, A.; Pati, S.; Narayana, C.; Ayana, R.; Kaushik, H.; Sah, R.; Garg, S.; Khanna, A.; Kumari, J.; Garg, L.; et al. A small bioactive glycoside inhibits epsilon toxin and prevents cell death. Dis. Model. Mech. 2019, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.F.; Yang, Y.N.; He, C.Y.; Chen, Z.F.; Yuan, Q.S.; Zhao, S.C.; Fu, Y.F.; Zhang, P.C.; Mao, D.B. New Caffeoylquinic Acid Derivatives and Flavanone Glycoside from the Flowers of Chrysanthemum morifolium and Their Bioactivities. Molecules 2019, 24, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.L.; Bian, X.K.; Qian, D.W.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, Z.H.; Guo, S.; Yan, H.; Wang, T.J.; Chen, Z.P.; Duan, J.A. Comparative study on differences of Paeonia lactiflora from different habitats based on fingerprint and chemometrics. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2019, 44, 3316–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chi, Y.H.; Niu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.B.; Zhang, C.E.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, L.F.; et al. Metabolomics Coupled with Multivariate Data and Pathway Analysis on Potential Biomarkers in Cholestasis and Intervention Effect of Paeonia lactiflora Pall. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, W. Anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects of paeoniflorin and total glucosides of paeony. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 207, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Wei, W.; Wang, N.P.; Wang, Q.T.; Chen, J.Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Hu, X.Y. Paeoniflorin suppresses inflammatory mediator production and regulates G protein-coupled signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes of collagen induced arthritic rats. Inflamm. Res. 2008, 57, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Wei, W.; Wang, Q.T.; Chen, J.Y.; Chen, Y. Cross-talk between MEK1/2-ERK1/2 signaling and G protein-couple signaling in synoviocytes of collagen-induced arthritis rats. Chin. Med. J. 2008, 121, 2278–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.D.; Jiang, M.Y.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.J.; Zhang, Y.W.; Yang, M.; Chen, J.Y.; Wei, W. Paeoniflorin-6’-O-benzene sulfonate down-regulates CXCR4-Gβγ-PI3K/AKT mediated migration in fibroblast-like synoviocytes of rheumatoid arthritis by inhibiting GRK2 translocation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 526, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.F.; Sun, F.F.; Jiang, L.F.; Bao, J.P.; Wu, L.D. Paeoniflorin inhibits IL-1β-induced MMP secretion via the NF-κB pathway in chondrocytes. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 1513–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chang, Q.; Huang, T.; Huang, C. Paeoniflorin inhibits IL-1β-induced expression of inflammatory mediators in human osteoarthritic chondrocyte. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 3306–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.F.; Chen, W.P.; Bao, J.P.; Wu, L.D. Paeoniflorin inhibits IL-1β-induced chondrocyte apoptosis by regulating the Bax/Bcl-2/caspase-3 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 6194–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Chung, W.T.; Choi, S.M.; Kim, K.T.; Yoo, K.S.; Yoo, Y.H. Clematis mandshurica protected to apoptosis of rat chondrocytes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 101, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Choi, S.M.; Chang, Y.S.; Kim, K.T.; Kim, T.H.; Park, H.T.; Park, B.S.; Sohn, Y.J.; Park, S.K.; Cho, S.H.; et al. A purified extract from Clematis mandshurica prevents staurosporin-induced downregulation of 14-3-3 and subsequent apoptosis on rat chondrocytes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 111, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Gao, X.; Xu, X.; Luo, Y.; Liu, M.; Xia, Y.; Dai, Y. Saponin-rich fraction from Clematis chinensis Osbeck roots protects rabbit chondrocytes against nitric oxide-induced apoptosis via preventing mitochondria impairment and caspase-3 activation. Cytotechnology 2013, 65, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Souto, E.B.; Cicala, C.; Caiazzo, E.; Izzo, A.A.; Novellino, E.; Santini, A. Polyphenols: A concise overview on the chemistry, occurrence, and human health. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2221–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Jia, J.; Jin, X.; Tong, W.; Tian, H. Resveratrol ameliorates inflammatory damage and protects against osteoarthritis in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, H.; Zhang, W.; Cui, Z.M.; Cui, S.Y.; Fan, J.B.; Zhu, X.H.; Liu, W. Resveratrol alleviates the interleukin-1β-induced chondrocytes injury through the NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; He, J.; Jiang, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Gu, H. Resveratrol Exerts Anti-Osteoarthritic Effect by Inhibiting TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway via the TLR4/Akt/FoxO1 Axis in IL-1β-Stimulated SW1353 Cells. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 2079–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; You, W.; Tang, X.; Li, X.; Gong, Z. Therapeutic effect of Resveratrol in the treatment of osteoarthritis via the MALAT1/miR-9/NF-κB signaling pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 2343–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csaki, C.; Keshishzadeh, N.; Fischer, K.; Shakibaei, M. Regulation of inflammation signalling by resveratrol in human chondrocytes in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 75, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuce, P.; Hosgor, H.; Rencber, S.F.; Yazir, Y. Effects of Intra-Articular Resveratrol Injections on Cartilage Destruction and Synovial Inflammation in Experimental Temporomandibular Joint Osteoarthritis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 79, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, N.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Newman, R.A.; Wolff, R.A.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Abbruzzese, J.L.; Ng, C.S.; Badmaev, V.; Kurzrock, R. Phase II trial of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4491–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Leong, D.J.; Xu, L.; He, Z.; Wang, A.; Navati, M.; Kim, S.J.; Hirsh, D.M.; Hardin, J.A.; Cobelli, N.J.; et al. Curcumin slows osteoarthritis progression and relieves osteoarthritis-associated pain symptoms in a post-traumatic osteoarthritis mouse model. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2016, 18, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y. Curcumin reduces inflammation in knee osteoarthritis rats through blocking TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signal pathway. Drug Dev. Res. 2019, 80, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gugliandolo, E.; Peritore, A.F.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cordaro, M.; Siracusa, R.; Fusco, R.; D’Amico, R.; Paola, R.D.; Schievano, C.; Cuzzocrea, S.; et al. Dietary Supplementation with Palmitoyl-Glucosamine Co-Micronized with Curcumin Relieves Osteoarthritis Pain and Benefits Joint Mobility. Animals 2020, 10, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamali, N.; Adib-Hajbaghery, M.; Soleimani, A. The effect of curcumin ointment on knee pain in older adults with osteoarthritis: A randomized placebo trial. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.J.; Kwon, E.S.; Lee, K.M.; Cho, C.; Lee, J.I.; Ryu, Y.B.; Youm, T.H.; Jeon, J.; Cho, M.R.; Jeong, S.Y.; et al. 3’-Sialyllactose as an inhibitor of p65 phosphorylation ameliorates the progression of experimental rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 4295–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.J.; Oh, E.; Cho, C.; Kwon, H.; Lee, C.G.; Jeon, J.; Lee, H.; Choi, S.; Han, S.J.; Nam, J.; et al. 3’-Sialyllactose prebiotics prevents skin inflammation via regulatory T cell differentiation in atopic dermatitis mouse models. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.; Kang, L.J.; Lee, K.M.; Cho, C.; Song, E.K.; Kim, W.; Park, T.J.; Yang, S. 3’-Sialyllactose protects against osteoarthritic development by facilitating cartilage homeostasis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reno, T.A.; Kim, J.Y.; Raz, D.J. Triptolide Inhibits Lung Cancer Cell Migration, Invasion, and Metastasis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 100, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liacini, A.; Sylvester, J.; Zafarullah, M. Triptolide suppresses proinflammatory cytokine-induced matrix metalloproteinase and aggrecanase-1 gene expression in chondrocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 327, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.Q.; Zhang, J.L. Therapeutic effects of triptolide from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f. on interleukin-1-beta-induced osteoarthritis in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 883, 173341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Zhang, L.; Shi, K. Triptolide prevents osteoarthritis via inhibiting hsa-miR-20b. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, B.A.; Dy, C.J.; Fabricant, P.D.; Valle, A.G. Long term safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability of hyaluronic acid injection in patients with painful osteoarthritis of the knee. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2012, 6, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.W.; Kuang, M.J.; Zhao, J.; Sun, L.; Lu, B.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.X.; Ma, X.L. Efficacy and safety of intraarticular hyaluronic acid and corticosteroid for knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 39, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, D.H.; Heck, B.E.; Shaffer, M.; Yoo, K.H.; Hur, J. PPAR-δ agonist affects adipo-chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells through the expression of PPAR-γ. Regen. Ther. 2020, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trebinjac, S.; Gharairi, M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment of Tendon and Ligament Injuries-clinical Evidence. Med. Arch. 2020, 74, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.; Zhao, X.; Son, Y.-O.; Yang, S. Therapeutic Single Compounds for Osteoarthritis Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020131

Lee H, Zhao X, Son Y-O, Yang S. Therapeutic Single Compounds for Osteoarthritis Treatment. Pharmaceuticals. 2021; 14(2):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020131

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hyemi, Xiangyu Zhao, Young-Ok Son, and Siyoung Yang. 2021. "Therapeutic Single Compounds for Osteoarthritis Treatment" Pharmaceuticals 14, no. 2: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020131

APA StyleLee, H., Zhao, X., Son, Y.-O., & Yang, S. (2021). Therapeutic Single Compounds for Osteoarthritis Treatment. Pharmaceuticals, 14(2), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020131