Novel Aminoguanidine Hydrazone Analogues: From Potential Antimicrobial Agents to Potent Cholinesterase Inhibitors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

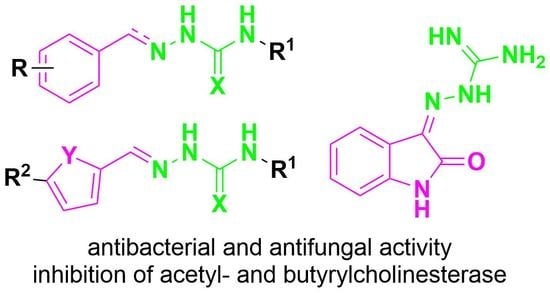

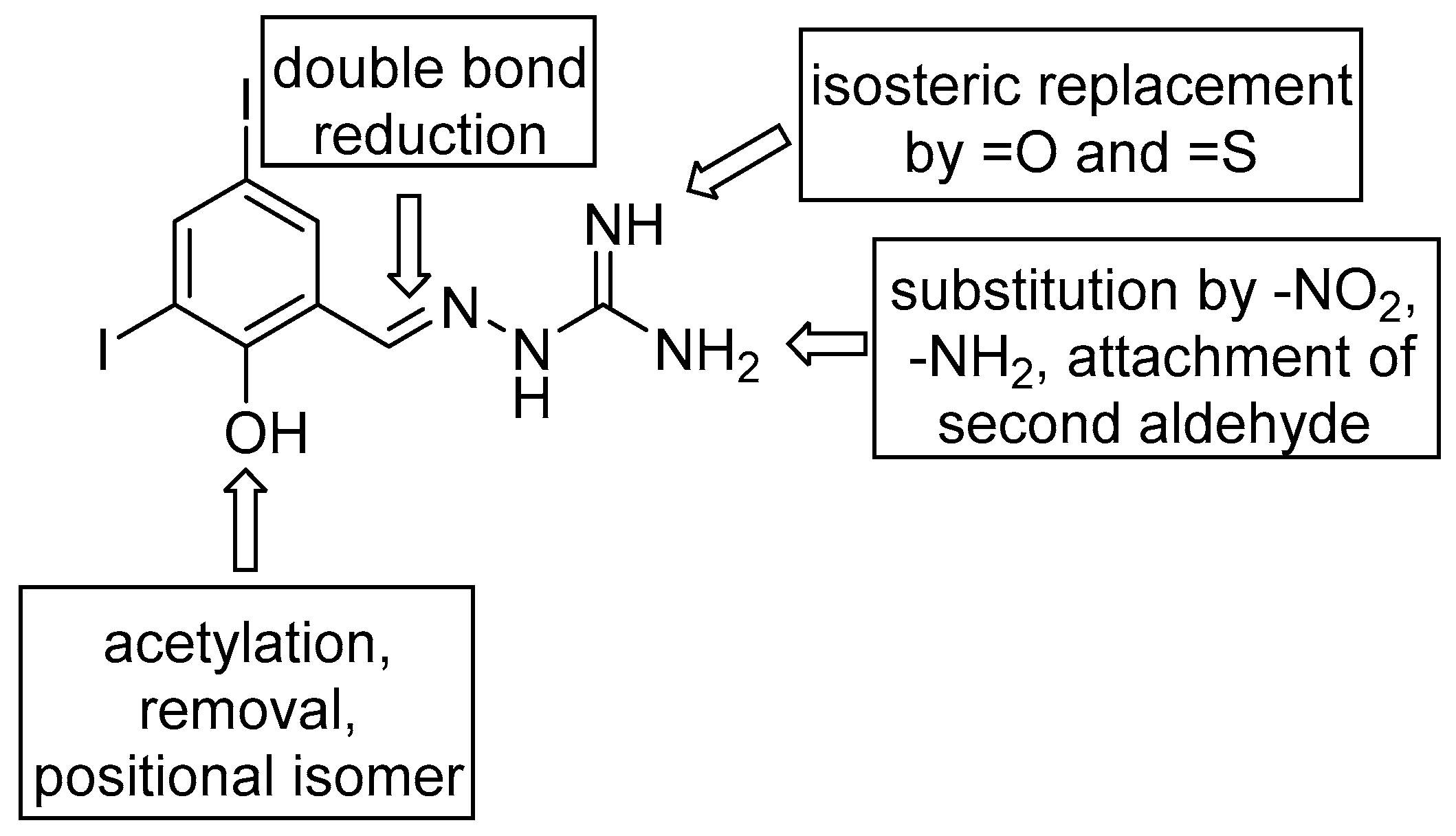

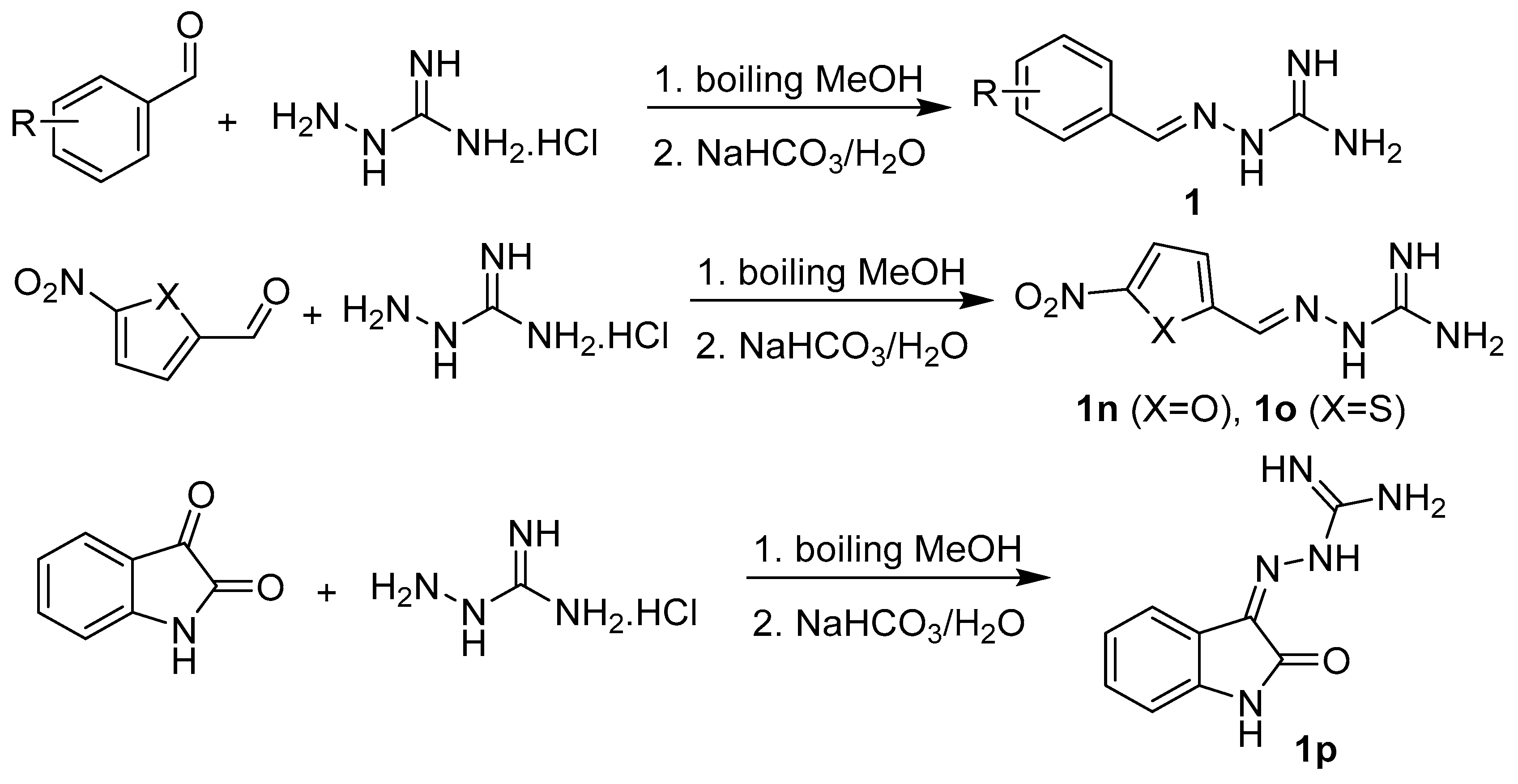

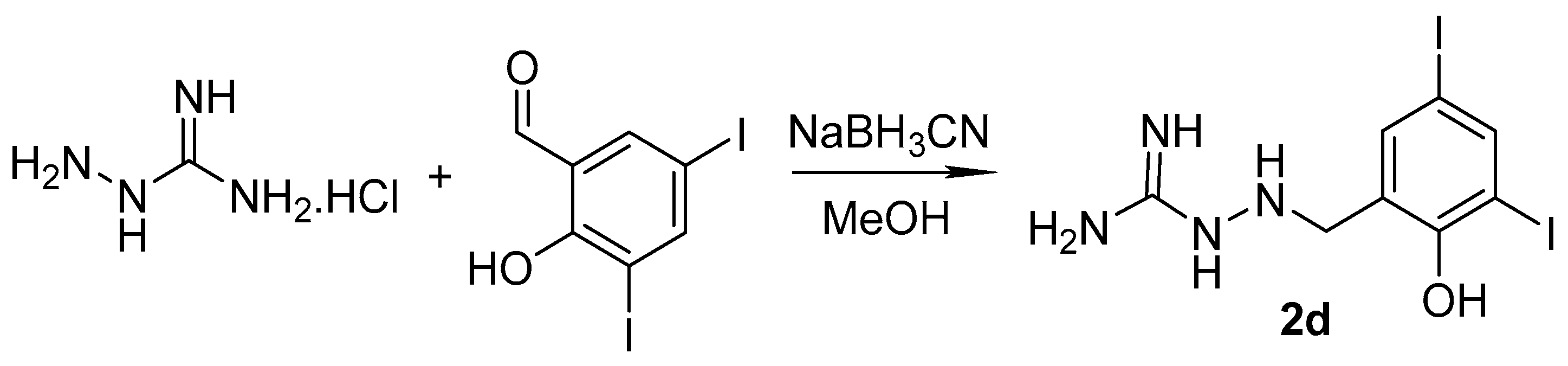

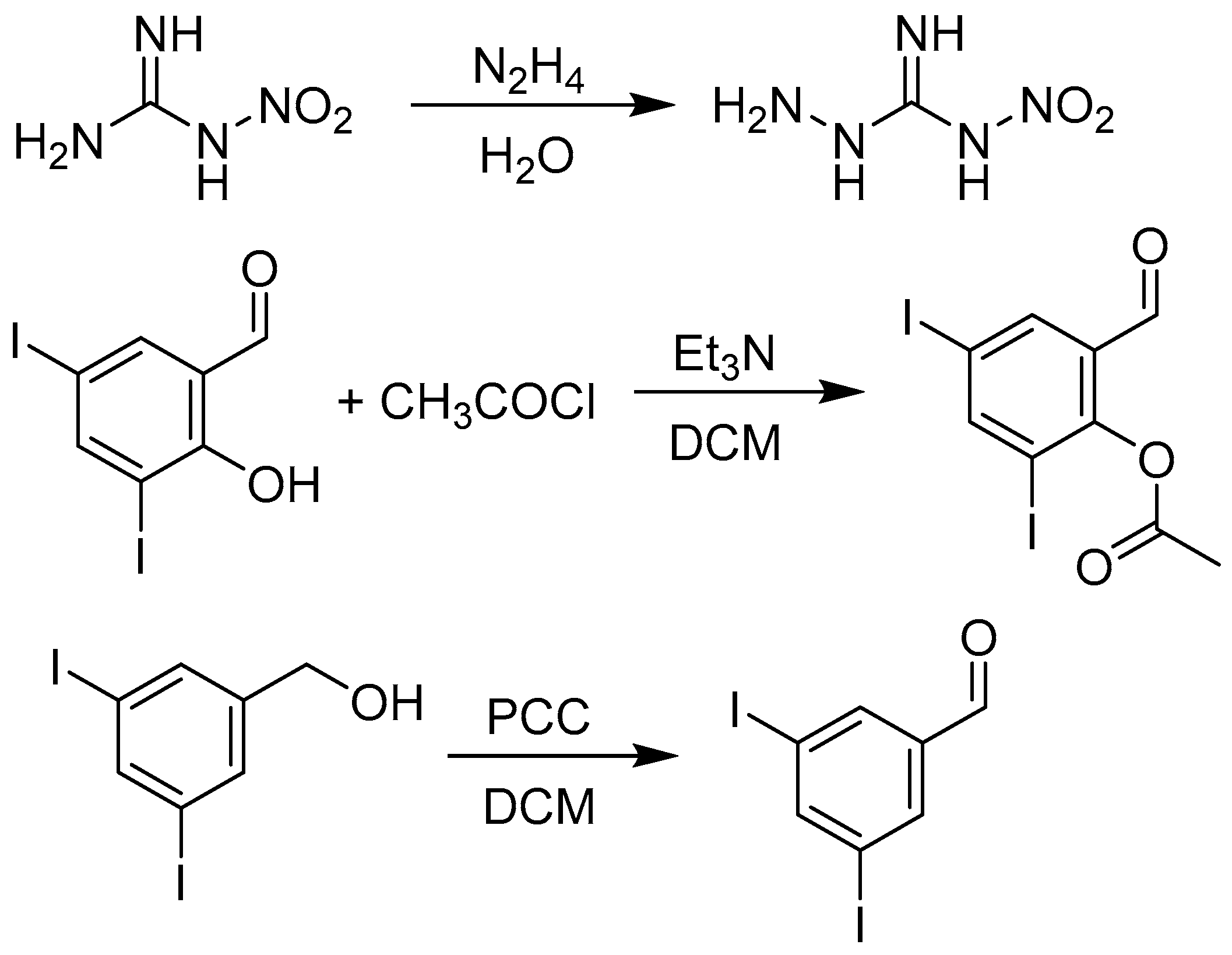

2.1. Design and Synthesis

2.2. Microbiology

2.2.1. Antibacterial Activity

2.2.2. Antifungal Activity

2.3. Inhibition of Acetyl- and Butyrylcholinesterase

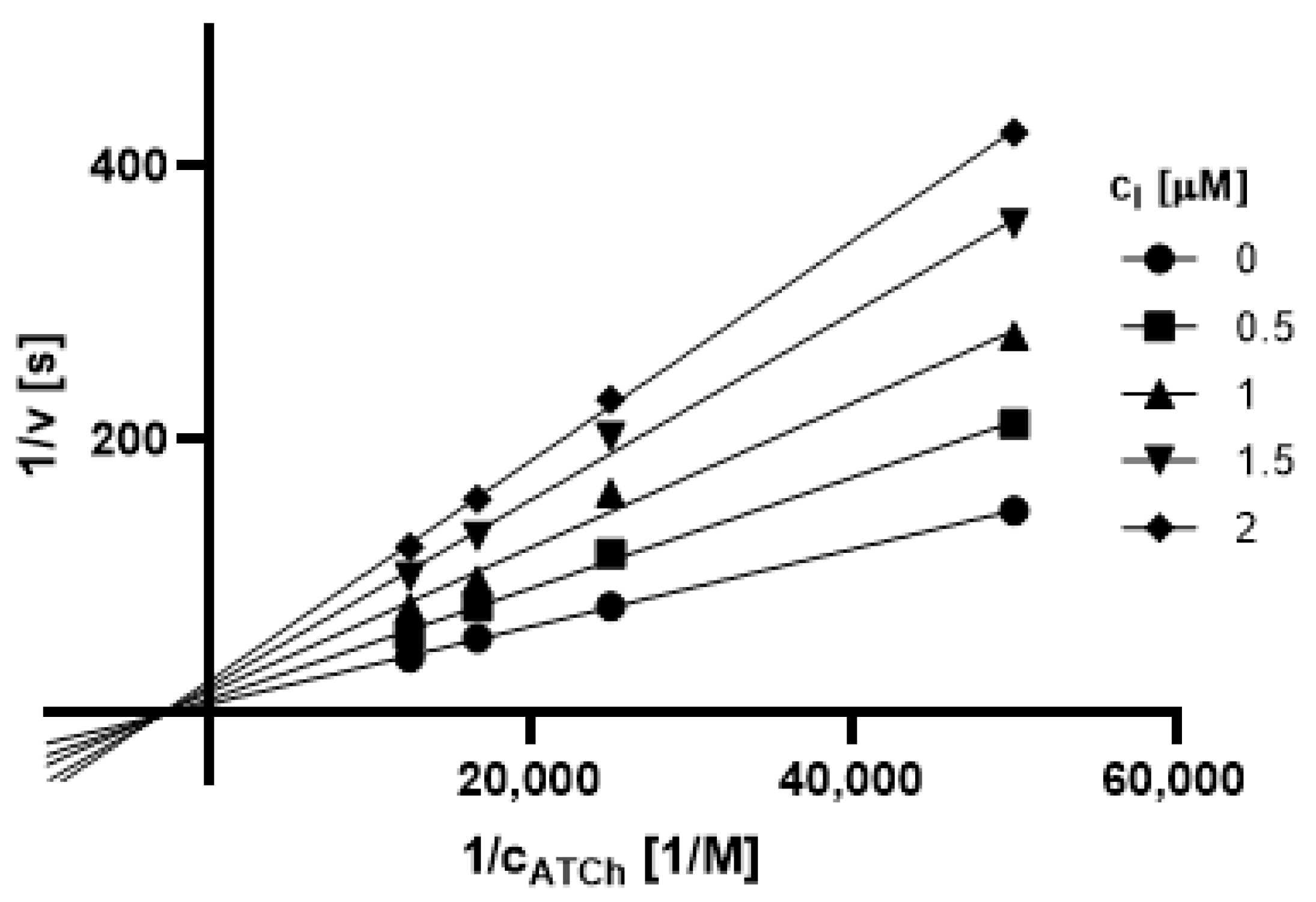

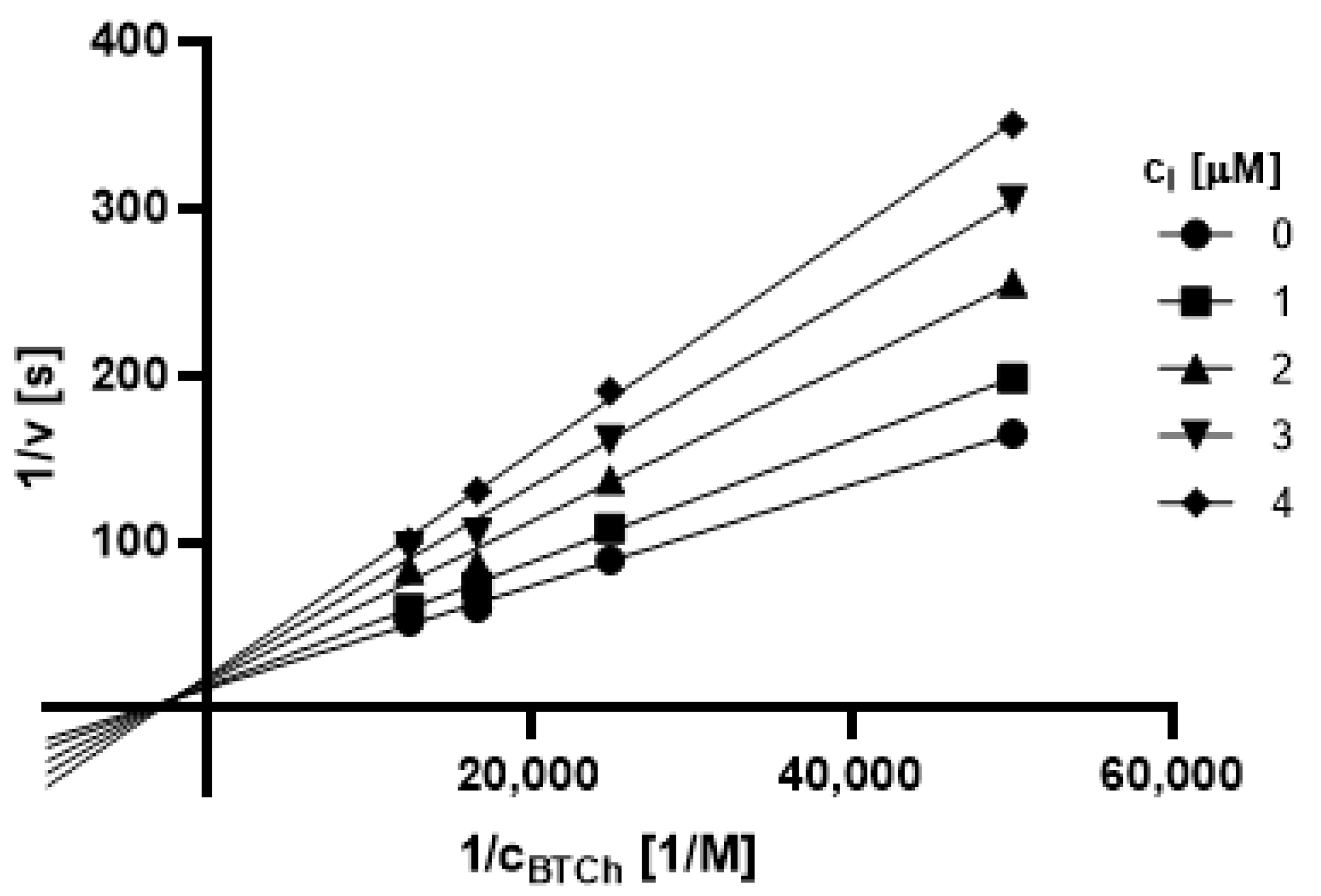

2.3.1. Type of Inhibition

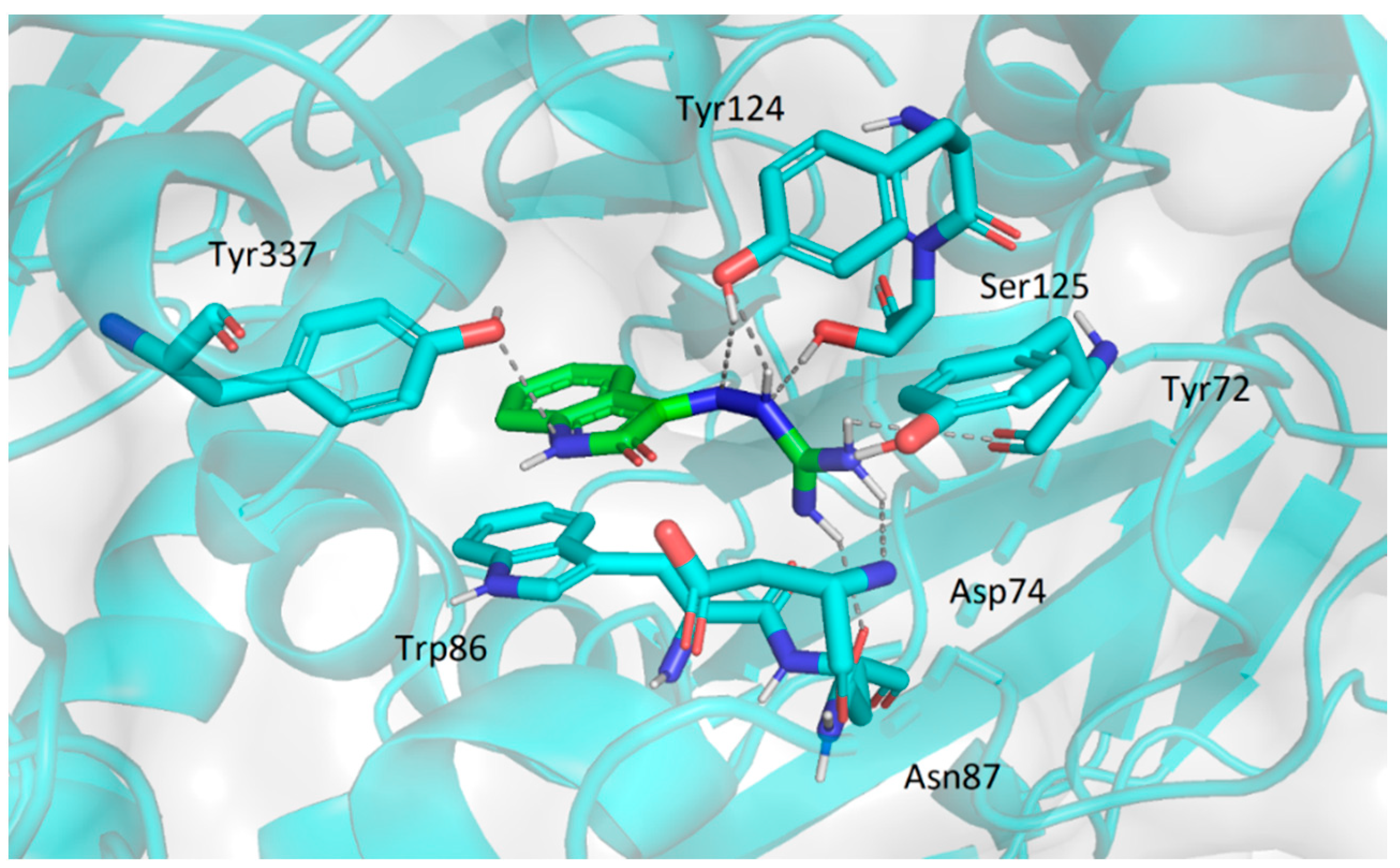

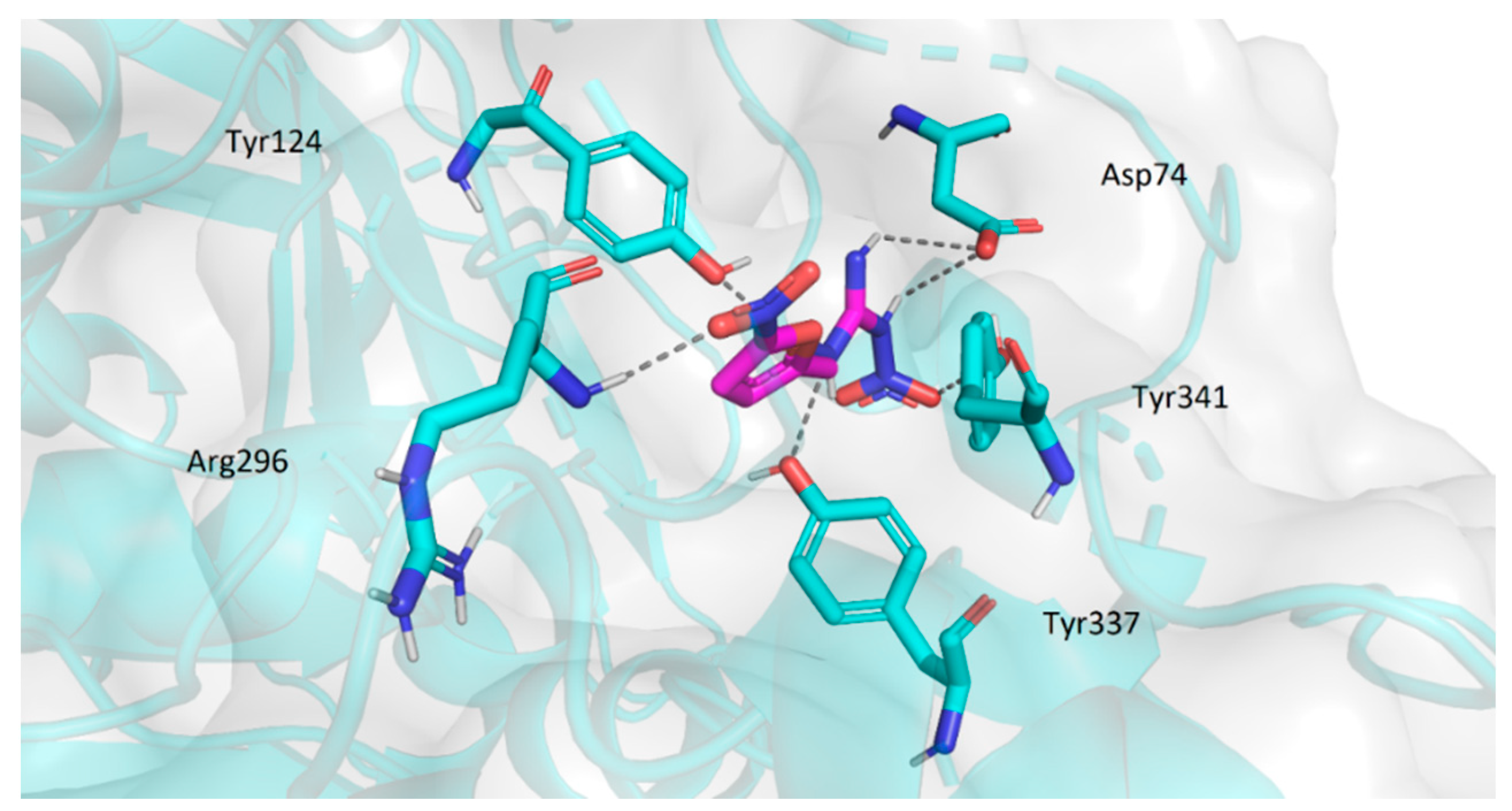

2.3.2. Molecular Docking Study

2.4. Cytotoxicity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General

3.1.2. Synthesis of Precursors

3.1.3. Synthesis of Targeted Derivatives 1–3

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity

3.2.1. Antibacterial Activity

3.2.2. Antifungal Activity

3.3. Evaluation of Acetyl- and Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibition

3.4. Molecular Docking

3.5. Cytotoxicity Determination

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Viegas-Junior, C.; Danuello, A.; da Silva Bolzani, V.; Barreiro, E.J.; Fraga, C.A. Molecular hybridization: A useful tool in the design of new drug prototypes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1829–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintus, E.; Kadlec, M.; Jovičić, M.; Sedmíková, M.; Ros-Santaella, J.L. Aminoguanidine Protects Boar Spermatozoa against the Deleterious Effects of Oxidative Stress. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vojtaššák, J.; Blaško, M.; Danišoviš, Ľ.; Čársky, J.; Ďuríková, M.; Respiská, V.; Waczulíková, I.; Böhmer, D. In Vitro Evaluation of the Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Resorcylidene Aminoguanidine in Human Diploid Cells B-HNF-1. Folia Biol. 2008, 54, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Song, X.; Ma, T.; Li, Y.; Bai, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Yuan, R.; Wen, Y.; Gao, J. Aminoguanidine inhibits IL-1β-induced protein expression of iNOS and COX-2 by blocking the NF-κB signaling pathway in rat articular chondrocytes. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 2623–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.-Y.; Chi, K.-Q.; Yu, Z.-K.; Liu, H.-Y.; Sun, L.-P.; Zheng, C.-J.; Piao, H.-R. Synthesis and biological evaluation of chalcone derivatives containing aminoguanidine or acylhydrazone moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 5920–5925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Wei, Z.-Y.; Wang, H.-M.; Guo, F.-Y.; Zheng, C.-J.; Piao, H.-R. Synthesis and biological evaluation of ursolic acid derivatives containing an aminoguanidine moiety. Med. Chem. Res. 2019, 28, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Fu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, H.; Liang, Z.; Deng, X. Synthesis, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities, and molecular docking studies of N-arylsulfonylindoles containing an aminoguanidine, a semicarbazide, and a thiosemicarbazide moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 166, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Song, M. Synthesis, antibacterial and anticancer activity, and docking study of aminoguanidines containing an alkynyl moiety. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020, 35, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.C.; Stevens, A.; Pi, H.; Khazandi, M.; Ogunniyi, A.D.; Young, K.A.; Baker, J.R.; McCluskey, S.N.; Page, S.W.; Trott, D.J.; et al. Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Antibiotic Activity of Asymmetric and Monomeric Robenidine Analogues. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 2573–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, N.; de Aquino, T.M.; de Araújo-Júnior, J.X.; da Silva-Júnior, E.; Gomes, E.A.; Severo Gomes, A.A.; Siqueira-Júnior, J.P.; Junior, F.J.B.M. Aminoguanidine hydrazones (AGH’s) as modulators of norfloxacin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus that overexpress NorA efflux pump. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 280, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Messeder, J.C.; Tinoco, L.W.; Figueroa-Villar, J.D.; Souza, E.M.; Santa Rita, R.; de Castro, S.L. Aromatic guanyl hydrazones: Synthesis, structural studies and in vitro activity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995, 5, 3079–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohilla, A.; Khare, G.; Tyagi, A.K. A combination of docking and cheminformatics approaches for the identification of inhibitors against 4′ phosphopantetheinyl transferase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amidi, S.; Esfahanizadeh, M.; Tabib, K.; Soleimani, Z.; Kobarfard, F. Rational Design and Synthesis of 1-(Arylideneamino)-4-aryl-1H-imidazole-2-amine Derivatives as Antiplatelet Agents. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Wang, Y.-Y. Antifungal agents. Part 5: Synthesis and antifungal activities of aminoguanidine derivatives of N-arylsulfonyl-3-acylindoles. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 7274–7277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.C.; Gao, M.J.; Huo, Q.; Ma, T.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.Z. Design, synthesis, and apoptosis-promoting effect evaluation of novel pyrazole with benzo[d]thiazole derivatives containing aminoguanidine units. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krátký, M.; Konečná, K.; Brablíková, M.; Janoušek, J.; Pflégr, V.; Maixnerová, J.; Trejtnar, F.; Vinšová, J. Iodinated 1,2-diacylhydrazines, benzohydrazide-hydrazones and their analogues as dual antimicrobial and cytotoxic agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 41, 116209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krátký, M.; Konečná, K.; Brokešová, K.; Maixnerová, J.; Trejtnar, F.; Vinšová, J. Optimizing the structure of (salicylideneamino)benzoic acids: Towards selective antifungal and anti-staphylococcal agents. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 159, 105732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krátký, M.; Konečná, K.; Janoušek, J.; Brablíková, M.; Janďourek, O.; Trejtnar, F.; Stolaříková, J.; Vinšová, J. 4-Aminobenzoic acid derivatives: Converting folate precursor to antimicrobial and cytotoxic agents. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krátký, M.; Bősze, S.; Baranyai, Z.; Stolaříková, J.; Vinšová, J. Synthesis and biological evolution of hydrazones derived from 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 5185–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukup, O.; Winder, M.; Killi, U.K.; Wsol, V.; Jun, D.; Kuca, K.; Tobin, G. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Drugs Acting on Muscarinic Receptors- Potential Crosstalk of Cholinergic Mechanisms During Pharmacological Treatment. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masunari, A.; Tavares, L.C. A new class of nifuroxazide analogues: Synthesis of 5-nitrothiophene derivatives with antimicrobial activity against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 4229–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R.J.; Stevens, A.J.; Young, K.A.; Russell, C.; Qvist, A.; Khazandi, M.; Wong, H.S.; Abraham, S.; Ogunniyi, A.D.; Page, S.W.; et al. Robenidine Analogues as Gram-Positive Antibacterial Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 2126–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şoica, C.; Fuliaş, A.; Vlase, G.; Dehelean, C.; Vlase, T.; Ledeţi, I. Synthesis and thermal behavior of new ambazone complexes with some transitional cations. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 118, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathaneni, V.; Gupta, V. Utilizing Drug Repurposing Against COVID-19—Efficacy, Limitations, and Challenges. Life Sci. 2020, 259, 118275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Jia, C.; Ma, Y.; Yang, D.; Ruic, C.; Qin, Z. Synthesis, insecticidal and fungicidal activities of methyl 2-(methoxyimino)-2-(2-((1-(N’- nitrocarbamimidoyl)-2-hydrocarbylidenehydrazinyl)methyl)phenyl)acetates. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 19916–19922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumler, W.D.; Sah, P.P.T. Nitroguanylhydrazones of Aldehydes: Their Antitubercular Activity, Ultraviolet Absorption Spectra and Structure. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 1952, 41, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, J.M.; Rival, Y.M.; Chayer, S.; Bourguignon, J.J.; Wermuth, C.G. Aminopyridazines as Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Neto, D.C.; de Souza Ferreira, M.; da Conceição Petronilho, E.; Alencar Lima, J.; de Azeredo, S.O.F.; de Oliveira Carneiro Brum, J.; do Nascimento, C.J.; Figueroa Villar, J.D. A new guanylhydrazone derivative as a potential acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for Alzheimer’s disease: Synthesis, molecular docking, biological evaluation and kinetic studies by nuclear magnetic resonance. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 33944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- da Conceição Petronilho, E.; do Nascimento Rennó, M.; Gonçalves Castro, N.; da Silva, F.M.R.; da Cunha Pinto, A.; Figueroa-Villar, J.D. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of guanylhydrazones as potential inhibitors or reactivators of acetylcholinesterase. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016, 31, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šekutor, M.; Mlinaric-Majerski, K.; Hrenar, T.; Tomic, S.; Primožič, I. Adamantane-substituted guanylhydrazones: Novel inhibitors of butyrylcholinesterase. Bioorg. Chem. 2012, 41–42, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krátký, M.; Štěpánková, Š.; Brablíková, M.; Svrčková, K.; Švarcová, M.; Vinšová, J. Novel Iodinated Hydrazide-hydrazones and their Analogues as Acetyl- and Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 2106–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krátký, M.; Svrčková, K.; Vu, Q.A.; Štěpánková, Š.; Vinšová, J. Hydrazones of 4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzohydrazide as New Inhibitors of Acetyl- and Butyrylcholinesterase. Molecules 2021, 26, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krátký, M.; Štěpánková, Š.; Houngbedji, N.-H.; Vosátka, R.; Vorčáková, K.; Vinšová, J. 2-Hydroxy-N-phenylbenzamides and their Esters Inhibit Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lineweaver, H.; Burk, D. The Determination of Enzyme Dissociation Constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1934, 56, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, H.; Silman, I.; Harel, M.; Rosenberry, T.L.; Sussman, J.L. Acetylcholinesterase: From 3D Structure to Function. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 187, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ordentlich, A.; Barak, D.; Kronman, C.; Ariel, N.; Segall, Y.; Velan, B.; Shafferman, A. Contribution of Aromatic Moieties of Tyrosine 133 and of the Anionic Subsite Tryptophan 86 to Catalytic Efficiency and Allosteric Modulation of Acetylcholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 2082–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicolet, Y.; Lockridge, O.; Masson, P.; Fontecilla-Camps, J.C.; Nachon, F. Crystal Structure of Human Butyrylcholinesterase and of Its Complexes with Substrate and Products. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 41141–41147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krátký, M.; Vinšová, J. Salicylanilide Ester Prodrugs as Potential Antimicrobial Agents—A Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 3494–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Melendez, J.A.; Golding, B.T. Optimisation of the Synthesis of Guanidines from Amines via Nitroguanidines Using 3,5-Dimethyl-N-nitro-1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine. Synthesis 2004, 10, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Zhao, Y. Conjugated Oligoyne-Bridged [60] Fullerene Molecular Dumbbells: Syntheses and Thermal and Morphological Properties. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1498–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.N.; McKay, A.F. Acylation of guanidines and guanylhydrazones. Canad. J. Chem. 1967, 45, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, H.; Wright, J. 466. 2-amino-1: 3: 4-indotriazine. The reaction between isatin and aminoguanidine. J. Chem. Soc. 1948, 2314–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, L.D.S.; Singh, S.; Singh, A. Novel clay-catalysed cyclisation of salicylaldehyde semicarbazones to 2H-benz[e]-1,3-oxazin-2-ones under microwave irradiation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 8551–8553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunan University; Aixi, H.; Jiao, Y.; Xiaoxiao, S.; Ailin, L.; Wenwen, K. 2-(2-Benzylidene Hydrazino)-5-(1,2,4-Triazole-1-yl)Thiazole, and Preparation and Applications Thereof. Patent No. CN104774199, 8 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ebetino, F.F.; Gever, G. Chemotherapeutic Nitrofurans. VII.1 The Formation of 5-Nitrofurfurylidene Derivatives of Some Aminoguanidines, Aminotriazoles, and Related Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1962, 27, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.C.; Guido, R.V.C.; Martinelli, T.F.; Goncalves, M.F.; Polli, M.C.; Botelho, K.C.A.; Varanda, E.A.; Colli, W.; Miranda, M.T.M.; Ferreira, E.I. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of potential antichagasic hydroxymethylnitrofurazone (NFOH-121): A new nitrofurazone prodrug. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 4779–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dann, O.; Möller, E.F. Über die wachstumshemmenden Eigenschaften von Nitroverbindungen. Chem. Ber. 1949, 82, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). EUCAST Discussion Document E. Dis 5.1. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibacterial agents by broth dilution. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). EUCAST Definitive Document EDEF 7.3.1. Method for the Determination of Broth Dilution Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antifungal Agents for Yeasts. Available online: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/AFST/Files/EUCAST_E_Def_7_3_1_Yeast_testing__definitive.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). EUCAST Definitive Document E. DEF 9.3.1. Method for the Determination of Broth Dilution Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antifungal Agents for Conidia Forming Moulds. Available online: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/AFST/Files/EUCAST_E_Def_9_3_1_Mould_testing__definitive.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Zdrazilova, P.; Stepankova, S.; Komers, K.; Ventura, K.; Cegan, A. Half-inhibition concentrations of new cholinesterase inhibitors. Z. Naturforsch. C J. Biosci. 2004, 59, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Autodock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Code | MIC [µM] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | MRSA | SE | EF | EC | KP | ACI | PA | |||||||||

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | |

| 1a | 500 | 500 | >500 | >500 | 250 | 250 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 1f | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 125 | 125 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| 1g | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 125 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| 1h | 250 | 500 | >500 | >500 | 125 | 250 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | 500 | 500 | >500 | >500 |

| 1i | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| 1j | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 250 |

| 1k | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 125 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 250 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 1l | 500 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | >500 | >500 |

| 1n | 62.5 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 62.5 | 125 | 500 | 500 | 62.5 | 125 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| 1o | 125 | 250 | 125 | 250 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 250 | 500 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 500 | 500 |

| 2a | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | >500 | >500 |

| 2b | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 250 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 2c | 15.62 | 15.62 | 15.62 | 15.62 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 31.25 | 31.25 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| 2e | 62.5 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 31.25 | 31.25 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 |

| 2h | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 125 | 125 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 2i | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 3d | 62.5 | 125 | 62.5 | 125 | 31.25 | 62.5 | 500 | 500 | 125 | 250 | 62.5 | 125 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| 3e | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 31.25 | 62.5 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 250 | 62.5 | 62.5 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 |

| PIP | 1.85 | 14.83 | >59.31 | 1.85 | 7.41 | >59.31 | >59.31 | 14.83 | ||||||||

| Code | MIC [µM] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | CK | CP | CT | TI | ||||||

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 120 h | |

| 1i | 500 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 500 | 62.5 | 125 |

| 1k | 250 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 125 | 250 |

| 1l | >500 | >500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 125 | 125 |

| 1o | >500 | >500 | 500 | 500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | 250 | 250 |

| 2a | 125 | 125 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 62.5 | 125 |

| 2d | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | >125 | 62.5 | 62.5 |

| 2e | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 |

| 2g | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | >500 | 250 | 250 |

| FLU * | 6.5 | 6.5 | >104.5 | >104.5 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 52.2 | 52.2 |

| Code | IC50 AChE (µM) | IC50 BuChE (µM) | Selectivity AChE/BuChE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 36.19 ± 0.10 | 44.95 ± 0.54 | 0.81 |

| 1b | 49.35 ± 0.11 | 99.12 ± 3.63 | 0.50 |

| 1c | 43.89 ± 0.76 | 41.47 ± 3.06 | 1.06 |

| 1d | 45.20 ± 1.60 | 13.89 ± 0.28 | 3.25 |

| 1e | 46.23 ± 2.26 | 5.57 ± 0.24 | 8.30 |

| 1f | 42.79 ± 1.33 | 30.61 ± 1.51 | 1.40 |

| 1g | 37.43 ± 0.73 | 45.22 ± 0.86 | 0.83 |

| 1h | 29.49 ± 0.93 | 62.28 ± 1.08 | 0.47 |

| 1i | 25.03 ± 0.50 | 19.76 ± 0.31 | 1.27 |

| 1j | 40.84 ± 0.80 | 61.74 ± 4.33 | 0.66 |

| 1k | 22.43 ± 0.67 | 11.68 ± 0.16 | 1.92 |

| 1l | 22.13 ± 0.55 | 5.42 ± 0.17 | 4.08 |

| 1m | 29.05 ± 2.49 | 3.57 ± 0.03 | 8.14 |

| 1n | 24.15 ± 0.75 | 203.99 ± 13.20 | 0.12 |

| 1o | 31.67 ± 1.34 | 286.05 ± 16.41 | 0.11 |

| 1p | 17.95 ± 0.90 | 17.51 ± 0.21 | 1.03 |

| 2a | 20.53 ± 0.48 | 4.52 ± 0.27 | 4.54 |

| 2b | 40.30 ± 0.85 | 46.28 ± 0.29 | 0.87 |

| 2c | 29.03 ± 1.19 | 85.54 ± 1.46 | 0.34 |

| 2d | 45.67 ± 1.70 | 41.52 ± 1.45 | 1.10 |

| 2e | 28.16 ± 0.98 | 1.69 ± 0.17 | 16.66 |

| 2f | 34.78 ± 0.04 | >500 | <0.07 |

| 2g | 54.93 ± 1.72 | 8.26 ± 0.21 | 6.65 |

| 2h | 30.72 ± 0.33 | 34.72 ± 0.35 | 0.88 |

| 2i | 52.22 ± 0.40 | 86.24 ± 0.39 | 0.61 |

| 3a | 41.08 ± 0.54 | 82.30 ± 3.02 | 0.50 |

| 3b | 24.75 ± 0.17 | >500 | <0.05 |

| 3c | 39.98 ± 2.56 | >500 | <0.08 |

| 3d | 36.60 ± 0.69 | >500 | <0.07 |

| 3e | 33.16 ± 0.06 | >500 | <0.07 |

| aminoguanidine | 75.14 ± 0.74 | 326.55 ± 18.02 | 0.23 |

| 1,3-diaminoguanidine | 41.71 ± 0.23 | 283.32 ± 8.94 | 0.15 |

| nitroaminoguanidine | 46.87 ± 0.44 | >500 | <0.09 |

| semicarbazide | 48.08 ± 0.84 | 364.63 ± 16.82 | 0.13 |

| thiosemicarbazide | 46.11 ± 1.10 | 327.78 ± 3.22 | 0.14 |

| rivastigmine | 56.10 ± 1.41 | 38.40 ± 1.97 | 1.46 |

| galantamine | 1.54 ± 0.02 | 2.77 ± 0.15 | 0.56 |

| Code | Affinity for AChE (kcal.mol−1) | Affinity for BuChE (kcal.mol−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1m | −7.7 | −8.1 |

| 1p | −9.1 | −7.6 |

| 2a | −8.5 | −8.2 |

| 2e | −8.0 | −8.3 |

| 3b | −8.0 | −7.2 |

| Code | IC50 [µM] | Code | IC50 [µM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1m | 56.52 | 2c | 9.84 |

| 1n | 10.41 | 2e | 119.6 |

| 1o | 5.27 | 3e | 29.78 |

| 1p | ˃500 | tamoxifen | 19.6 |

| 2a | 31.29 |

| Code | EC50 [µM] | Code | EC50 [µM] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1m | 21.26 | 2a | 30.43 |

| 1n | 3.55 | 2c | 5.44 |

| 1o | 0.79 | 2e | 131.9 |

| 1p | 129.5 | 3e | 5.25 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krátký, M.; Štěpánková, Š.; Konečná, K.; Svrčková, K.; Maixnerová, J.; Švarcová, M.; Janďourek, O.; Trejtnar, F.; Vinšová, J. Novel Aminoguanidine Hydrazone Analogues: From Potential Antimicrobial Agents to Potent Cholinesterase Inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14121229

Krátký M, Štěpánková Š, Konečná K, Svrčková K, Maixnerová J, Švarcová M, Janďourek O, Trejtnar F, Vinšová J. Novel Aminoguanidine Hydrazone Analogues: From Potential Antimicrobial Agents to Potent Cholinesterase Inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals. 2021; 14(12):1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14121229

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrátký, Martin, Šárka Štěpánková, Klára Konečná, Katarína Svrčková, Jana Maixnerová, Markéta Švarcová, Ondřej Janďourek, František Trejtnar, and Jarmila Vinšová. 2021. "Novel Aminoguanidine Hydrazone Analogues: From Potential Antimicrobial Agents to Potent Cholinesterase Inhibitors" Pharmaceuticals 14, no. 12: 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14121229

APA StyleKrátký, M., Štěpánková, Š., Konečná, K., Svrčková, K., Maixnerová, J., Švarcová, M., Janďourek, O., Trejtnar, F., & Vinšová, J. (2021). Novel Aminoguanidine Hydrazone Analogues: From Potential Antimicrobial Agents to Potent Cholinesterase Inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals, 14(12), 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14121229