Assessment of the Effect of Four Kneeling Chair Angle Combinations on Muscle Activity and Perceived Discomfort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

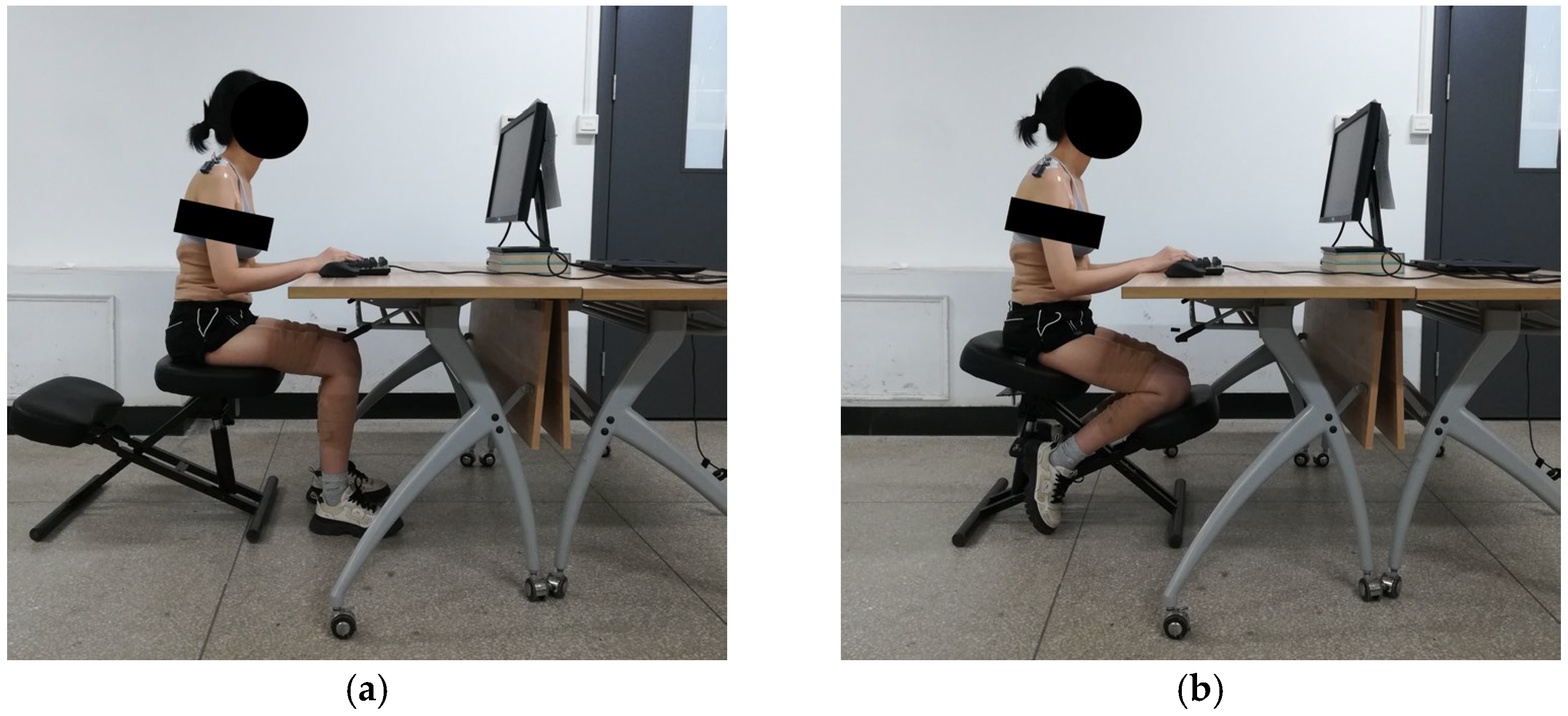

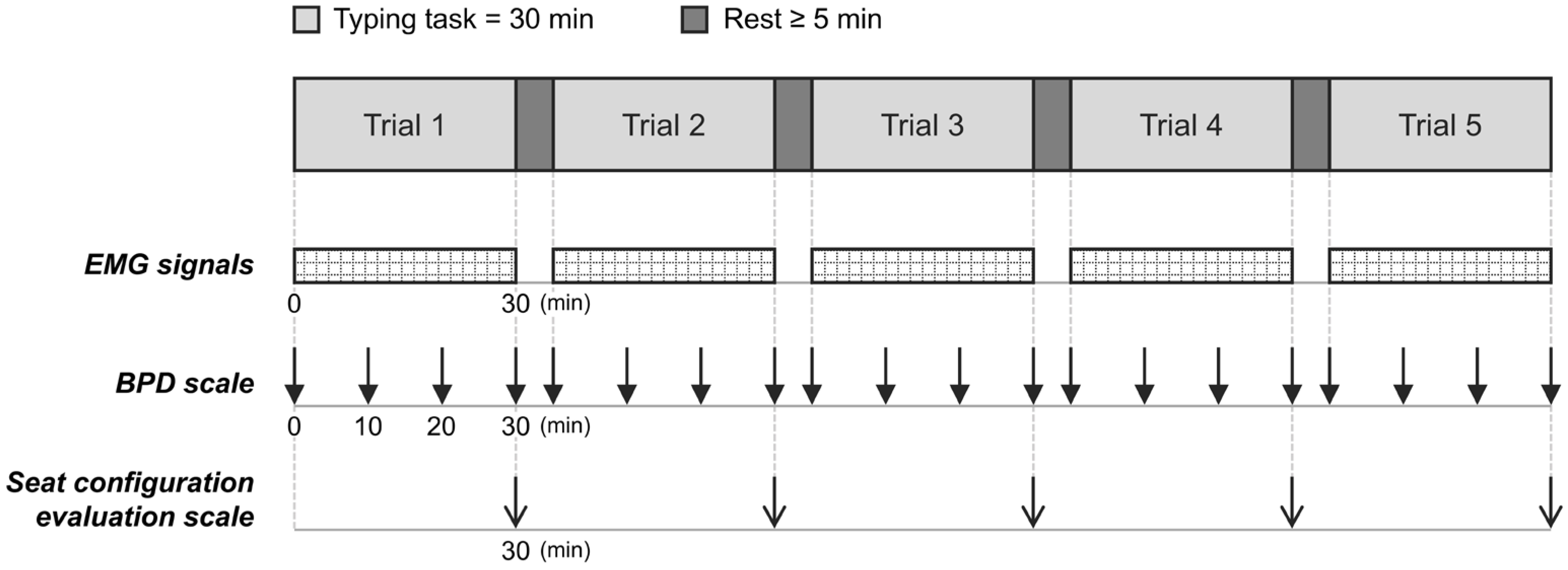

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. EMG Signals

| Muscle | Electrode Placement | MVC Trial |

|---|---|---|

| Tr | 2 cm lateral to the midpoint of the line between C7 and the acromion [29] | Subjects shrugged the shoulders in a sitting position [30]. |

| LES | 3 cm lateral to L1 [31] | Subjects extended the back in a prone position with the legs secured, the trunk suspended, and the arms crossed over the chest [32]. |

| LM | L5 level, parallel to the line between the posterior superior iliac spine and the L1–L2 interspinous space [33] | |

| EO | 15 cm lateral to the umbilicus [34], aligned at an 80-degree angle to the horizontal [35] | Subjects performed trunk flexion as well as left and right twists in a supine trunk-lifted position, with the feet secured and the knees flexed [36,37]. |

| RF | The midpoint of the line between the anterior superior iliac spine and the superior part of the patella [38] | Subjects performed hip flexion and knee extension simultaneously in a sitting position [39]. |

| GM | The midpoint of the line between the medial side of the popliteal fossa and the medial side of the Achilles tendon insertion [40] | Subjects performed single-leg toe standing, with balanced support provided (if necessary) [41,42]. |

| GL | 1/3 of the line between the head of the fibula and the heel [38] |

2.3.2. BPD Scale

2.3.3. Seat Configuration Evaluation Scale

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

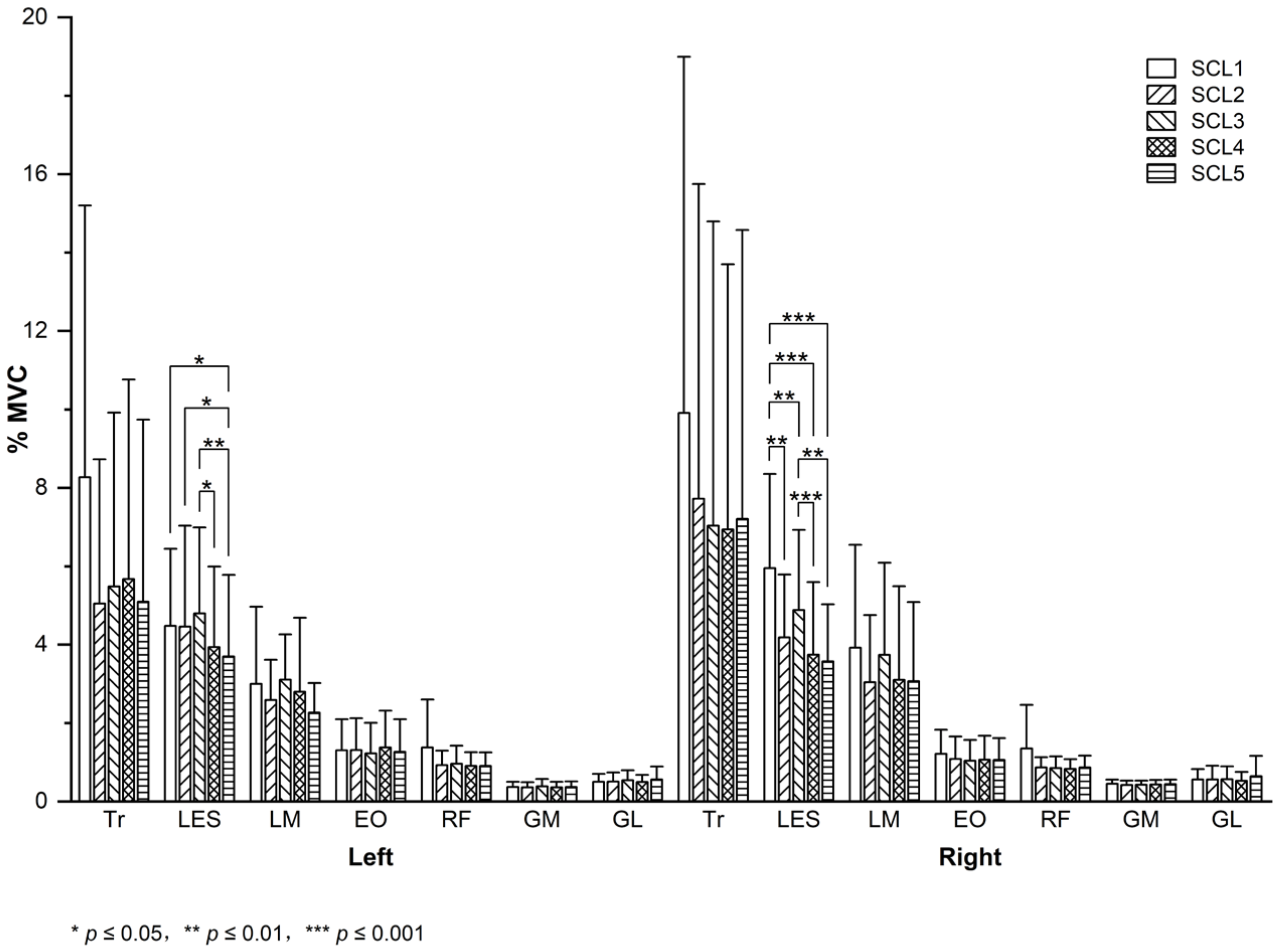

3.1. Muscle Activity

3.2. Perceived Discomfort

3.3. Seat Configuration Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMG | surface electromyography |

| BPD | body part discomfort |

| LES | lumbar erector spinae |

| BMI | body mass index |

| SCL1/SCL2/SCL3/SCL4/SCL5 | seat configuration level 1/2/3/4/5 |

| SA10/SA20/SA30 | seat pan angle of 10/20/30 degrees |

| KA20/KA30/KA35/KA40 | knee rest angle of 20/30/35/40 degrees |

| Tr | trapezius |

| LM | lumbar multifidus |

| EO | external oblique |

| RF | rectus femoris |

| GM | gastrocnemius medial |

| GL | gastrocnemius lateralis |

| MVC | maximum voluntary contraction |

| C7 | the seventh cervical vertebra |

| L1/L2/L5 | the first/second/fifth lumbar vertebra |

| RMS | root mean square |

| OBD | overall body discomfort |

| BPDF | body part discomfort frequency |

| BPDS | body part discomfort severity |

| LSD | the least significant difference |

| M | mean |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- Shikdar, A.A.; Al-Kindi, M.A. Office Ergonomics: Deficiencies in Computer Workstation Design. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2007, 13, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mork, P.J.; Westgaard, R.H. Back Posture and Low Back Muscle Activity in Female Computer Workers: A Field Study. Clin. Biomech. 2009, 24, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillastrini, P.; Mugnai, R.; Bertozzi, L.; Costi, S.; Curti, S.; Guccione, A.; Mattioli, S.; Violante, F.S. Effectiveness of an Ergonomic Intervention on Work-Related Posture and Low Back Pain in Video Display Terminal Operators: A 3 Year Cross-over Trial. Appl. Ergon. 2010, 41, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niekerk, S.-M.; Louw, Q.A.; Hillier, S. The Effectiveness of a Chair Intervention in the Workplace to Reduce Musculoskeletal Symptoms. A Systematic Review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, J.J. Alterations of the Lumbar Curve Related to Posture and Seating. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1953, 35-A, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.C. The Seated Man (Homo Sedens) the Seated Work Position. Theory and Practice. Appl. Ergon. 1981, 12, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, J.K.; Tecklin, J.S. Comparison of Lumbar Curves When Sitting on the Westnofa Balans Multi-Chair, Sitting on a Conventional Chair, and Standing. Phys. Ther. 1986, 66, 1365–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettany-Saltikov, J.; Warren, J.; Jobson, M. Ergonomically Designed Kneeling Chairs Are They Worth It? : Comparison of Sagittal Lumbar Curvature in Two Different Seating Postures. In Research into Spinal Deformities 6; Dangerfield, P.H., Ed.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 140, pp. 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D.L.; Gillis, D.K.; Portney, L.G.; Romanow, M.; Sanchez, A.S. Comparison of Integrated Electromyographic Activity and Lumbar Curvature during Standing and during Sitting in Three Chairs. Phys. Ther. 1989, 69, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaucher, M.; Isner-Horobeti, M.-E.; Demattei, C.; Alonso, S.; Herisson, C.; Kouyoumdjian, P.; van Dieen, J.H.; Dupeyron, A. Effect of a Kneeling Chair on Lumbar Curvature in Patients with Low Back Pain and Healthy Controls: A Pilot Study. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 58, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhsous, M.; Lin, F.; Bankard, J.; Hendrix, R.W.; Hepler, M.; Press, J. Biomechanical Effects of Sitting with Adjustable Ischial and Lumbar Support on Occupational Low Back Pain: Evaluation of Sitting Load and Back Muscle Activity. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2009, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.; O’Sullivan, L.; O’Sullivan, P.; Dankaerts, W.; O’Sullivan, K. Does Using a Chair Backrest or Reducing Seated Hip Flexion Influence Trunk Muscle Activity and Discomfort? A Systematic Review. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 1115–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, M.; Page, A. System to Measure the Use of the Backrest in Sitting-Posture Office Tasks. Appl. Ergon. 2000, 31, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soderberg, G.L.; Blanco, M.K.; Cosentino, T.L.; Kurdelmeier, K.A. An EMG Analysis of Posterior Trunk Musculature during Flat and Anteriorly Inclined Sitting. Hum. Factors 1986, 28, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Tang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Bao, W. Analysis of Kneeling Sitting of Children in the Working State Based on Surface Electromyography and Visual Distance. J. Donghua Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 48, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cram, J.R.; Vinitzky, I. Effects of Chair Design on Back Muscle Fatigue. J. Occup. Rehabil. 1995, 5, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, C.; Korbon, G.A.; DeGood, D.E.; Rowlingson, J.C. The Balans Chair and Its Semi-Kneeling Position: An Ergonomic Comparison with the Conventional Sitting Position. Spine 1987, 12, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishu, R.R.; Hallbeck, M.S.; Riley, M.W.; Stentz, T.L. Seating Comfort and Its Relationship to Spinal Profile. A Pilot Study. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 1991, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridger, R.S. Postural Adaptations to a Sloping Chair and Work Surface. Hum. Factors 1988, 30, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Bao, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, X. Comfort Kneeling Seat for School-Age Children. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Sci.) 2024, 29, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houcke, J.; Schouten, A.; Steenackers, G.; Vandermeulen, D.; Pattyn, C.; Audenaert, E. Computer-Based Estimation of the Hip Joint Reaction Force and Hip Flexion Angle in Three Different Sitting Configurations. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 63, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, G.; Hedge, A. Effect of Workstation Configuration on Musculoskeletal Discomfort, Productivity, Postural Risks, and Perceived Fatigue in a Sit-Stand-Walk Intervention for Computer-Based Work. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 90, 103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, D.; Dunk, N.; Callaghan, J. Stability Ball versus Office Chair: Comparison of Muscle Activation and Lumbar Spine Posture during Prolonged Sitting. Hum. Factors 2006, 48, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingma, I.; van Dieën, J. Static and Dynamic Postural Loadings during Computer Work in Females: Sitting on an Office Chair versus Sitting on an Exercise Ball. Appl. Ergon. 2009, 40, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, C.; Shen, X.; Sun, H. (Eds.) Experimental Psychology, 3rd ed.; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019; ISBN 978-7-117-28164-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hermens, H.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of Recommendations for SEMG Sensors and Sensor Placement Procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjodahl, J.; Kvist, J.; Gutke, A.; Oberg, B. The Postural Response of the Pelvic Floor Muscles during Limb Movements: A Methodological Electromyography Study in Parous Women without Lumbopelvic Pain. Clin. Biomech. 2009, 24, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietrys, D.M.; Gerg, M.J.; Dropkin, J.; Gold, J.E. Mobile Input Device Type, Texting Style and Screen Size Influence Upper Extremity and Trapezius Muscle Activity, and Cervical Posture While Texting. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 50, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.; Vasseljen, O.; Westgaard, R.H. The Influence of Electrode Position on Bipolar Surface Electromyogram Recordings of the Upper Trapezius Muscle. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993, 67, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alowa, Z.; Elsayed, W. The Impact of Forward Head Posture on the Electromyographic Activity of the Spinal Muscles. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.; Barrett, M.; De Carvalho, D. Effect of a Dynamic Seat Pan Design on Spine Biomechanics, Calf Circumference and Perceived Pain during Prolonged Sitting. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 97, 103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, S.; Barnes, J.; Pike, K.; De Carvalho, D. The Relation between the Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon Onset Angle and Lumbar Spine Muscle Reflex Onset Time in Response to 30 Min of Slumped Sitting. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2021, 58, 102545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Foa, J.L.; Forrest, W.; Biedermann, H.J. Muscle Fibre Direction of Longissimus, Iliocostalis and Multifidus: Landmark-Derived Reference Lines. J. Anat. 1989, 163, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Radebold, A.; Cholewicki, J.; Panjabi, M.; Patel, T. Muscle Response Pattern to Sudden Trunk Loading in Healthy Individuals and in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine 2000, 25, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, I.; Gardner-Morse, M.; Henry, S.; Badger, G. Decrease in Trunk Muscular Response to Perturbation with Preactivation of Lumbar Spinal Musculature. Spine 2000, 25, 1957–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, M.R.; Cardenas, A.K.; Albert, W.J. A Biomechanical Analysis of Active vs Static Office Chair Designs. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 96, 103481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Afari, M.; Li, H.; Anwer, S.; Li, D.; Yu, Y.; Mi, H.; Wuni, I. Assessment of a Passive Exoskeleton System on Spinal Biomechanics and Subjective Responses during Manual Repetitive Handling Tasks among Construction Workers. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SENIAM. Available online: http://www.seniam.org/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- McGill, S.; Juker, D.; Kropf, P. Appropriately Placed Surface EMG Electrodes Reflect Deep Muscle Activity (Psoas, Quadratus Lumborum, Abdominal Wall) in the Lumbar Spine. J. Biomech. 1996, 29, 1503–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainoldi, A.; Melchiorri, G.; Caruso, I. A Method for Positioning Electrodes during Surface EMG Recordings in Lower Limb Muscles. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Z.; Mazloumi, A.; Sharifnezhad, A.; Jafari, A.H.; Kazemi, Z.; Keihani, A.; Mohebbi, I. Determining the Interactions between Postural Variability Structure and Discomfort Development Using Nonlinear Analysis Techniques during Prolonged Standing Work. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 96, 103489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Z.; Allahyari, T.; Azghani, M.R.; Khalkhali, H. Influence of Unstable Footwear on Lower Leg Muscle Activity, Volume Change and Subjective Discomfort during Prolonged Standing. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 53, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, E.N.; Bishop, R.P. A Technique for Assessing Postural Discomfort. Ergonomics 1976, 19, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.; Dankaerts, W.; O’Sullivan, P.; O’Sullivan, L.; O’Sullivan, K. The Effect of a Backrest and Seatpan Inclination on Sitting Discomfort and Trunk Muscle Activation in Subjects with Extension-Related Low Back Pain. Ergonomics 2014, 57, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeto, G.; Straker, L.; O’Sullivan, P. During Computing Tasks Symptomatic Female Office Workers Demonstrate a Trend towards Higher Cervical Postural Muscle Load than Asymptomatic Office Workers: An Experimental Study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, K.B.; Nazarahari, M.; Rouhani, H. K-Score: A Novel Scoring System to Quantify Fatigue-Related Ergonomic Risk Based on Joint Angle Measurements via Wearable Inertial Measurement Units. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 102, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.; Callaghan, J. Elimination of Electrocardiogram Contamination from Electromyogram Signals: An Evaluation of Currently Used Removal Techniques. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2006, 16, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.V.; Lomond, K.V.; Hitt, J.R.; DeSarno, M.J.; Bunn, J.Y.; Henry, S.M. Effects of Low Back Pain and of Stabilization or Movement-System-Impairment Treatments on Induced Postural Responses: A Planned Secondary Analysis of a Randomised Controlled Trial. Man. Ther. 2016, 21, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wu, Y.; He, W.; Liu, S.; Tao, D. Assessing Mouse, Trackball, Touchscreen and Leap Motion in Ship Vibration Conditions: A Comparison of Task Performance, Upper Limb Muscle Activity and Perceived Fatigue and Usability. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2024, 101, 103585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benli, T.; Kara, D.; Dulger, E.; Bilgin, S. Electromyography Study of Six Parts of the Latissimus Dorsi during Reaching Tasks While Seated: A Comparison between Healthy Subjects and Stroke Patients. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2023, 70, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Coenen, P.; Howie, E.; Lee, J.; Williamson, A.; Straker, L. A Detailed Description of the Short-Term Musculoskeletal and Cognitive Effects of Prolonged Standing for Office Computer Work. Ergonomics 2018, 61, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yu, S.; Yang, H.; Pei, H.; Zhao, C. Effects of Long-Duration Sitting with Limited Space on Discomfort, Body Flexibility, and Surface Pressure. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2017, 58, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, C.G.; Deeb, J.M.; Hartman, B.; Woolley, S.; Drury, C.E.; Gallagher, S. Symmetric and Asymmetric Manual Materials Handling. Part 1: Physiology and Psychophysics. Ergonomics 1989, 32, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, S.; Williams, K. Impact of Seating Posture on User Comfort and Typing Performance for People with Chronic Low Back Pain. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2008, 38, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | Study | The Kneeling Chair vs. the Traditional Chair |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle activity | Bennett et al. [9] | No significant difference in erector spinae muscle activity. |

| Soderberg et al. [14] | Significantly less trapezius and erector spinae muscle activity using the kneeling chair. | |

| Cram et al. [16] | Significantly greater lumbar paraspinal muscle activity using the kneeling chair; no significant differences in cervical and thoracic paraspinal muscle activity. | |

| Lander et al. [17] | Significantly greater cervical paraspinal muscle activity using the kneeling chair; no significant difference in lumbar paraspinal muscle activity. | |

| Wang et al. [15] | Significantly greater erector spinae and gastrocnemius muscle activity using the kneeling chair. | |

| Subjective (dis)comfort | Lander et al. [17] | A non-significant preference for the traditional chair in terms of overall and lower back comfort. |

| Soderberg et al. [14] | A non-significant preference for the kneeling chair in terms of comfort. | |

| Wang et al. [15] | A non-significant trend towards greater comfort in the overall body, upper back, lower back, buttocks, thighs, and lower legs using the traditional chair; a non-significant trend towards greater neck comfort using the kneeling chair. | |

| Bishu et al. [18] | A non-significant trend towards greater discomfort in the upper, middle, and lower back using the kneeling chair. | |

| Bridger et al. [19] | Significantly greater comfort using the kneeling chair in combination with both horizontal and inclined work surfaces. |

| Study | Subjects | Unsupported Seat Configurations | Experimental Task | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | Sample size: 17 healthy subjects (8 females and 9 males) Age (years): 19–30, M = 22.82 | Traditional sitting configuration (SCL1); kneeling configurations: SA10–KA20 (SCL2), SA10–KA35 (SCL3), SA20–KA20 (SCL4), and SA20–KA35 (SCL5) combinations. | Typing for 30 min | LES muscle activity, shoulder discomfort, upper and lower back discomfort, BPDF back, BPDS back: kneeling < traditional (significant). BPDF back: SCL2 > SCL3 (significant). Upper and lower back discomfort, BPDF back: SCL2 > SCL4 (significant). LES muscle activity, upper and lower back discomfort, BPDF back: SCL2 > SCL5 (significant). LES muscle activity: SCL3 > SCL4 (significant); SCL3 > SCL5 (significant). Shoulder discomfort: SCL4 < SCL5 (significant). |

| Tang et al. [20] | Sample size: 6 healthy subjects (6 females) Age (years): 7–9 | Kneeling configurations: SA10–KA30, SA20–KA30, SA30–KA30, SA20–KA20, and SA20–KA40 combinations. | Handwriting on paper for 60 min | LES muscle activity: SA10–KA30 > SA20–KA30 > SA30–KA30 (significant); SA20–KA30 > SA20–KA20 (non-significant). Gastrocnemius muscle activity: SA10–KA30 < SA20–KA30 < SA30–KA30 (significant); SA20–KA30 < SA20–KA40 < SA20–KA20 (significant). |

| Wang et al. [15] | Sample size: 6 healthy subjects (6 females) Age (years): M = 8 | Traditional sitting configuration; kneeling configuration: SA10–KA30 combination. | Handwriting on paper for 60 min | LES and gastrocnemius muscle activity: kneeling > traditional (significant). Upper and lower back comfort: kneeling < traditional (non-significant). |

| Soderberg et al. [14] | Sample size: 20 healthy subjects (10 females and 10 males) Age (years): 22–33, M = 24.4 | Traditional sitting configuration; kneeling configurations: SA10 and SA20, with an unmentioned knee rest angle. | Minimal-typing computer interaction for 15 min (20 subjects) or 30 min (10 subjects) | Tr and LES muscle activity: kneeling < traditional (significant); SA10 > SA20 (significant). Subjective comfort: kneeling > traditional (non-significant); SA10 < SA20 (non-significant). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lei, X.; Li, J.; Cong, J.; Ren, M.; Xiang, Z. Assessment of the Effect of Four Kneeling Chair Angle Combinations on Muscle Activity and Perceived Discomfort. Sensors 2026, 26, 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030970

Lei X, Li J, Cong J, Ren M, Xiang Z. Assessment of the Effect of Four Kneeling Chair Angle Combinations on Muscle Activity and Perceived Discomfort. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):970. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030970

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Xiaoxiao, Jutao Li, Jingchen Cong, Mengyang Ren, and Zhongxia Xiang. 2026. "Assessment of the Effect of Four Kneeling Chair Angle Combinations on Muscle Activity and Perceived Discomfort" Sensors 26, no. 3: 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030970

APA StyleLei, X., Li, J., Cong, J., Ren, M., & Xiang, Z. (2026). Assessment of the Effect of Four Kneeling Chair Angle Combinations on Muscle Activity and Perceived Discomfort. Sensors, 26(3), 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030970