Physiological Assessment of Mental Stress in Construction Workers Under High-Risk Working Conditions: ECG-Based Field Measurements on Inexperienced Scaffolders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Mental Stress Measurement in the Construction Field

2.2. Potential of HRV in Mental Stress Measurement

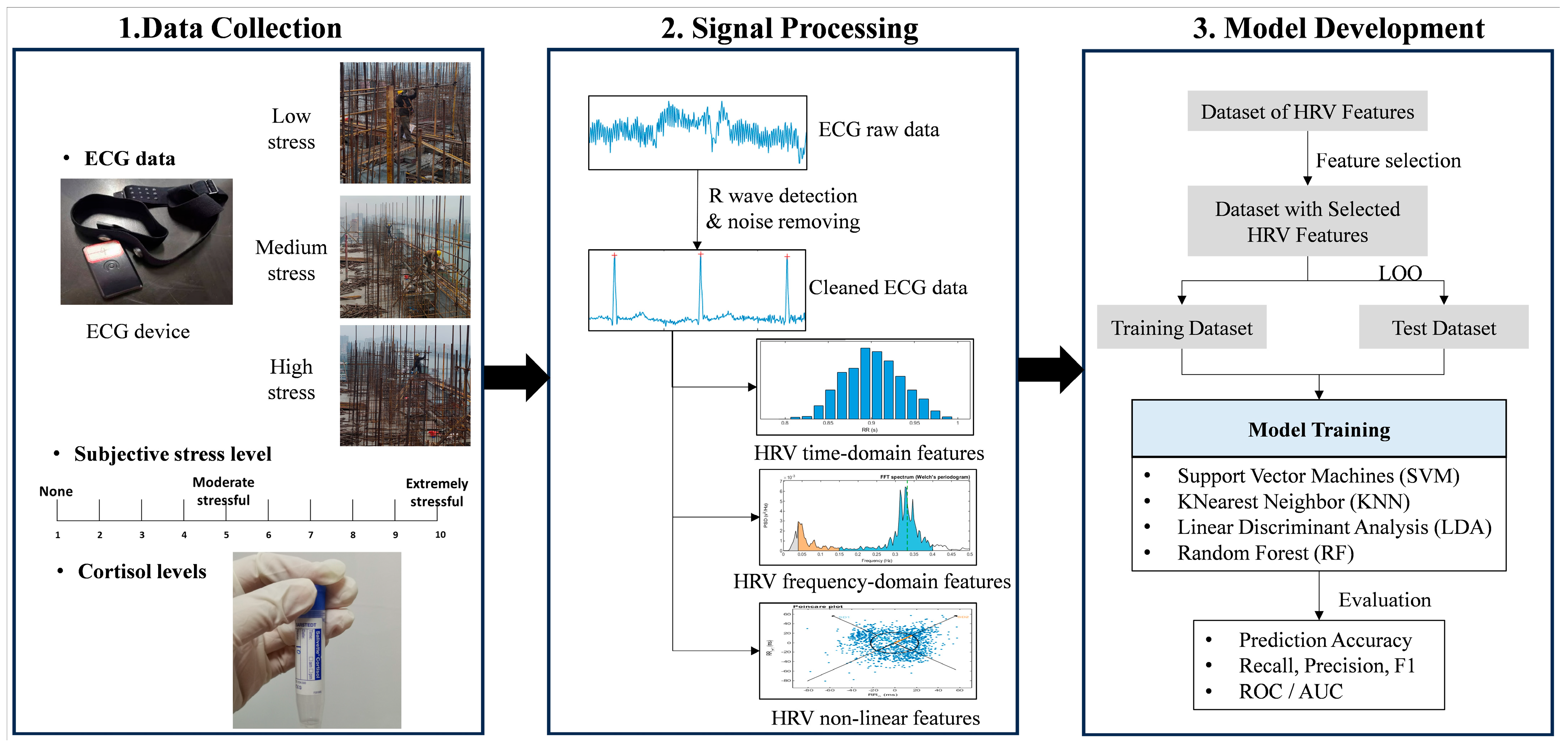

3. Methodology

3.1. Subjects and Apparatus

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

3.3. HRV Feature Computation

3.4. Classification Model Development

4. Results

4.1. Validation of Stress Level Differences Across Experimental Conditions

4.2. Accuracy and Evaluation of Classification Models

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sternberg, R.J. Cognitive Psychology; Harcourt Brace College Publishers: Orlando, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Love, P.E.D.; Edwards, D.J.; Irani, Z. Work stress, support, and mental health in construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.-Y.; Liang, Q.; Olomolaiye, P. Impact of Job Stressors and Stress on the Safety Behavior and Accidents of Construction Workers. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04015019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Skitmore, M.; Leung, T. Manageability of stress among construction project participants. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2005, 12, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y.; Luo, X.; He, X.; Yin, W. Development of Construction Workers Job Stress Scale to Study and the Relationship between Job Stress and Safety Behavior: An Empirical Study in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burlet-Vienney, D.; Chinniah, Y.; Bahloul, A.; Roberge, B. Design and application of a 5 step risk assessment tool for confined space entries. Saf. Sci. 2015, 80, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.; Chan, Y.-S.; Yuen, K.-W. Impacts of Stressors and Stress on the Injury Incidents of Construction Workers in Hong Kong. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Wu, X.; Ci, H.; Liu, Q.; Yao, Y. Empirical research on the influencing factors of the occupational stress for construction workers. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 61, 012102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, C.; Camacho Vega, J.; Gómez -Salgado, J.; García-Iglesias, J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Allande-Cussó, R.; Martín Pereira, J.; Ruiz Frutos, C. Stress, fear, and anxiety among construction workers: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1226914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbe, O.O.; Harvey, C.M.; Ikuma, L.H.; Aghazadeh, F. Modeling the relationship between occupational stressors, psychosocial/physical symptoms and injuries in the construction industry. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2011, 41, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahayadhas, A.; Sundaraj, K.; Murugappan, M. Detecting Driver Drowsiness Based on Sensors: A Review. Sensors 2012, 12, 16937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebelli, H.; Hwang, S.; Lee, S. EEG-based workers’ stress recognition at construction sites. Autom. Constr. 2018, 93, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, W. Simultaneous monitoring of physical and mental stress for construction tasks using physiological measures. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebelli, H.; Choi, B.; Lee, S. Application of Wearable Biosensors to Construction Sites. I: Assessing Workers’ Stress. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocco, J.; Le, M.D.; Paeng, D.-G. A Systemic Review of Available Low-Cost EEG Headsets Used for Drowsiness Detection. Front. Neuroinformatics 2020, 14, 553352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, M.; Payne, B.R.; Strayer, D.L. A Review of Psychophysiological Measures to Assess Cognitive States in Real-World Driving. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Pirke, K.M.; Hellhammer, D.H. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’--a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 1993, 28, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedovic, K.; Renwick, R.; Mahani, N.K.; Engert, V.; Lupien, S.J.; Pruessner, J.C. The Montreal Imaging Stress Task: Using functional imaging to investigate the effects of perceiving and processing psychosocial stress in the human brain. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005, 30, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, C.; Lee, S.; Sun, C.; Jebelli, H.; Yang, K.; Choi, B. Wearable Sensing Technology Applications in Construction Safety and Health. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 03119007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katmah, R.; Al-Shargie, F.; Tariq, U.; Babiloni, F.; Al-Mughairbi, F.; Al-Nashash, H. A Review on Mental Stress Assessment Methods Using EEG Signals. Sensors 2021, 21, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-G.; Cheon, E.; Bai, D.; Lee, Y.; Koo, B.H. Stress and Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis and Review of the Literature. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.; Almeida, P.R.; Cunha, J.P.S.; Aguiar, A. Heart rate variability metrics for fine-grained stress level assessment. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2017, 148, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The, A.F.; Reijmerink, I.; van der Laan, M.; Cnossen, F. Heart rate variability as a measure of mental stress in surgery: A systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmohammadi, S.; Maleki, A. Continuous mental stress level assessment using electrocardiogram and electromyogram signals. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 68, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.P.; Zhang, B.; Zhan, C.A.A. Short-term HRV in young adults for momentary assessment of acute mental stress. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2020, 57, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, A.; Klockner, D.K.; Toft, Y. New Employees Accident and Injury Rates in Australia: A review of the literature. Statement Purp. Object. 2020, XXIX, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, A.; Zagoory-Sharon, O.; Feldman, R.; Lewis, J.G.; Weller, A. Measuring cortisol in human psychobiological studies. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 90, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarvainen, M.P.; Niskanen, J.-P.; Lipponen, J.A.; Ranta-aho, P.O.; Karjalainen, P.A. Kubios HRV—Heart rate variability analysis software. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2014, 113, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Tompkins, W.J. A Real-Time QRS Detection Algorithm. In IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1985; Volume BME-32, pp. 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, T.; Lenis, G.; Reichensperger, P.; Beran, T.; Doessel, O.; Deml, B. Electrocardiographic features for the measurement of drivers’ mental workload. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 61, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Bigger, J.T.; Camm, A.J.; Kleiger, R.E.; Malliani, A.; Moss, A.J.; Schwartz, P.J. Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, clinical use. Eur. Heart J. 1996, 17, 354–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.T.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.Z.; Zhang, W.Q. Detection of mental fatigue state with wearable ECG devices. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 119, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenick, D. Tests and Measurements: The T-test. Strength Cond. J. 1990, 12, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterman, M.; Tamber-Rosenau, B.J.; Chiu, Y.C.; Yantis, S. Avoiding non-independence in fMRI data analysis: Leave one subject out. NeuroImage 2010, 50, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D.M. The Problem of Overfitting. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kaber, D. Evaluation of Strategies for Integrated Classification of Visual-Manual and Cognitive Distractions in Driving. Hum. Factors 2016, 58, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, N.S. An Introduction to Kernel and Nearest-Neighbor Nonparametric Regression. Am. Stat. 1992, 46, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.R. Statistical Pattern Recognition; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lotte, F.; Congedo, M.; Lécuyer, A.; Lamarche, F.; Arnaldi, B. A review of classification algorithms for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 2007, 4, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romine, W.L.; Schroeder, N.L.; Graft, J.; Yang, F.; Sadeghi, R.; Zabihimayvan, M.; Kadariya, D.; Banerjee, T. Using Machine Learning to Train a Wearable Device for Measuring Students’ Cognitive Load during Problem-Solving Activities Based on Electrodermal Activity, Body Temperature, and Heart Rate: Development of a Cognitive Load Tracker for Both Personal and Classroom Use. Sensors 2020, 20, 4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmohammadi, S.; Maleki, A. Stress detection using ECG and EMG signals: A comprehensive study. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 193, 105482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, H.; Zhou, X.Z.; Ou, X.H.; Liu, Y.; Xue, C.Q. Detection of mental fatigue state using heart rate variability and eye metrics during simulated flight. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2021, 31, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Umer, W.; Wang, H.; Xing, X.; Zhao, S.; Hou, J. Identification and classification of construction equipment operators’ mental fatigue using wearable eye-tracking technology. Autom. Constr. 2020, 109, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan-Ming, L.; Chih-Jen, L. A study on reduced support vector machines. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2003, 14, 1449–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, D.; Zong, M.; Zhang, S. Efficient kNN classification algorithm for big data. Neurocomputing 2016, 195, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, S.; Li, H.; Umer, W.; Antwi-Afari Maxwell, F.; Mehmood, I.; Yu, Y.; Haas, C.; Wong Arnold Yu, L. Identification and Classification of Physical Fatigue in Construction Workers Using Linear and Nonlinear Heart Rate Variability Measurements. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04023057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.-M.; Kim, T.-S. Gender Plays Significant Role in Short-Term Heart Rate Variability. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2015, 40, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Rowell, T.; Williams, D.; Love, G.; McKinley, P.; Sloan, R.; Ryff, C. Race Differences in Age-Trends of Autonomic Nervous System Functioning. J. Aging Health 2013, 25, 839–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiselev, A.R.; Zhuravlev, M.O.; Runnova, A.E. Assessment of frequency components of ECG waveform variability: Are there prospects for research into cardiac regulation processes? Russ. Open Med. J. 2024, 13, e0412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, M.O.; Runnova, A.E.; Mironov, S.A.; Zhuravleva, J.A.; Kiselev, A.R. Continuous Estimation of Heart Rate Variability from Electrocardiogram and Photoplethysmogram Signals with Oscillatory Wavelet Pattern Method. Sensors 2025, 25, 5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HRV Feature | Unit | Description (Equation) |

|---|---|---|

| Time domain features | ||

| mRR | [ms] | The mean of RR intervals ) |

| SDRR | [ms] | The standard deviation of RR intervals ) |

| RMSSD | [ms] | The square root of the mean squared differences between successive RR intervals ) |

| pNN50 | [%] | Number of interval differences of successive RR intervals greater than 50 ms () |

| mHR | [bpm] | Average heart rate |

| Frequency-domain features | ||

| VLF | [ms2] | Absolute powers of very-low-frequency band (0–0.04 Hz) |

| LF | [ms2] | Absolute powers of low-frequency band (0.04–0.15 Hz) |

| HF | [ms2] | Absolute powers of high-frequency band (0.15–0.4 Hz) |

| TP | [ms2] | The total energy of RR intervals |

| LF/HF | [n.u.] | The ratio between LF and HF band powers |

| nLF | [n.u.] | Normalized low-frequency power |

| nHF | [n.u.] | Normalized high-frequency power |

| Non-linear features | ||

| SD1 | [ms] | The standard deviation for T direction in Poincaré plot |

| SD2 | [ms] | The standard deviation for L direction in Poincaré plot |

| HRV Features | Low (Mean ± SD) | Medium | High | Low–Medium | Low–High | Medium–High | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mean ± SD) | (Mean ± SD) | t | p | t | p | t | p | ||

| mRR | 748.40 ± 142.97 | 746.56 ± 139.84 | 738.45 ± 124.93 | 0.308 | 0.762 | 0.944 | 0.357 | 1.437 | 0.167 |

| SDRR | 24.23 ± 11.22 | 20.33 ± 8.54 | 21.15 ± 9.63 | 2.090 | 0.050 | 3.060 | 0.006 | −0.921 | 0.369 |

| RMSSD | 22.71 ± 12.46 | 21.92 ± 12.37 | 20.58 ± 12.64 | 1.287 | 0.213 | 0.852 | 0.405 | 1.301 | 0.209 |

| pNN50 | 6.39 ± 11.71 | 5.75 ± 12.85 | 5.67 ± 12.87 | 0.741 | 0.468 | 1.777 | 0.092 | 0.122 | 0.904 |

| mHR | 77.86 ± 11.86 | 80.10 ± 12.36 | 82.03 ± 13.00 | −2.303 | 0.033 | 1.345 | 0.194 | −3.256 | 0.004 |

| VLF | 40.11 ± 31.65 | 30.10 ± 23.12 | 20.26 ± 18.48 | 2.290 | 0.034 | 1.813 | 0.086 | −1.345 | 0.194 |

| LF | 231.17 ± 30.07 | 108.00 ± 10.52 | 72.09 ± 56.94 | 2.360 | 0.029 | 2.319 | 0.032 | −0.157 | 0.877 |

| HF | 289.97 ± 31.35 | 288.38 ± 34.38 | 251.51 ± 31.81 | 0.287 | 0.777 | 1.443 | 0.165 | 1.659 | 0.114 |

| TP | 568.31 ± 42.56 | 380.97 ± 39.07 | 362.49 ± 35.80 | 2.524 | 0.021 | 3.304 | 0.007 | 1.341 | 0.196 |

| LF/HF | 3.19 ± 0.54 | 1.33 ± 0.28 | 1.10 ± 0.21 | 2.154 | 0.044 | 2.027 | 0.057 | 0.472 | 0.642 |

| nLF | 41.22 ± 3.15 | 38.63 ± 2.59 | 33.13 ± 2.63 | 1.540 | 0.140 | 0.538 | 0.597 | −1.563 | 0.135 |

| nHF | 55.77 ± 3.52 | 60.45 ± 2.66 | 65.11 ± 2.74 | −1.679 | 0.106 | −0.900 | 0.380 | 1.338 | 0.197 |

| SD1 | 16.23 ± 8.92 | 15.65 ± 8.85 | 14.68 ± 9.03 | 1.309 | 0.206 | 1.014 | 0.323 | 0.789 | 0.440 |

| SD2 | 29.52 ± 14.49 | 25.54 ± 11.29 | 23.71 ± 9.03 | 1.468 | 0.158 | 1.351 | 0.193 | −1.185 | 0.251 |

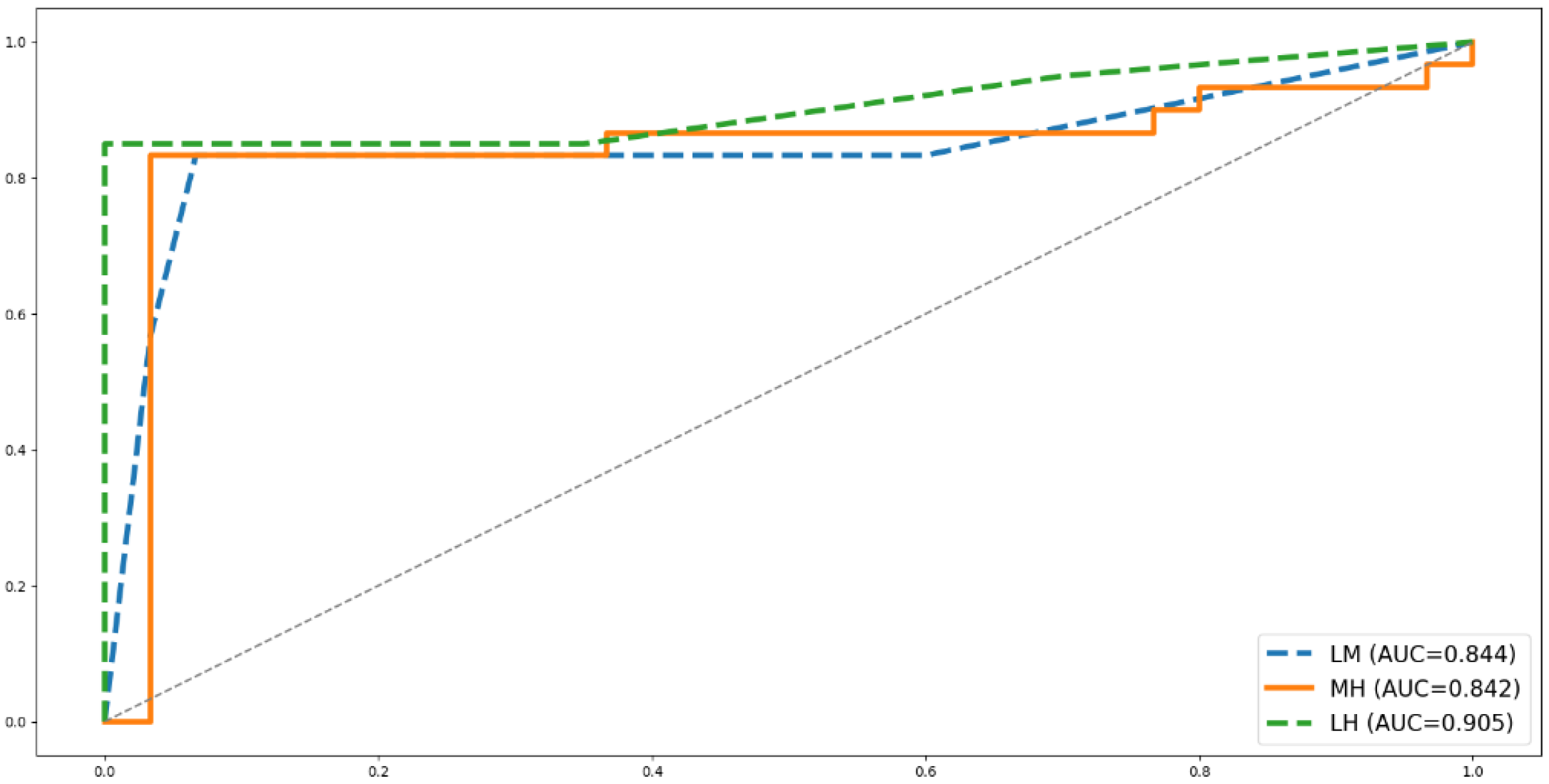

| Applied HRV Features | Classification Accuracy | Model Evaluations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LM | mRR, SDRR, VLF, LF, TP, LF/HF | SVM, 85.00% | Recall = 0.850, Precision = 0.850, F1 = 0.850, AUC = 0.844 |

| LH | SDRR, RMSSD, VLF, LF, TP, LF/HF | KNN, 92.50% | Recall = 1.000, Precision = 0.870, F1 = 0.930, AUC = 0.905 |

| MH | mHR, mRR, RMSSD, VLF, HF, TP, nLF, nHF | KNN, 87.50% | Recall = 0.950, Precision = 0.826, F1 = 0.884, AUC = 0.842 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lei, L.; He, S.; Hou, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ouyang, Y. Physiological Assessment of Mental Stress in Construction Workers Under High-Risk Working Conditions: ECG-Based Field Measurements on Inexperienced Scaffolders. Sensors 2026, 26, 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030949

Lei L, He S, Hou R, Zhu Y, Zhao J, Ouyang Y. Physiological Assessment of Mental Stress in Construction Workers Under High-Risk Working Conditions: ECG-Based Field Measurements on Inexperienced Scaffolders. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):949. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030949

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Likai, Shiyi He, Ruihao Hou, Yifan Zhu, Jiaqi Zhao, and Yewei Ouyang. 2026. "Physiological Assessment of Mental Stress in Construction Workers Under High-Risk Working Conditions: ECG-Based Field Measurements on Inexperienced Scaffolders" Sensors 26, no. 3: 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030949

APA StyleLei, L., He, S., Hou, R., Zhu, Y., Zhao, J., & Ouyang, Y. (2026). Physiological Assessment of Mental Stress in Construction Workers Under High-Risk Working Conditions: ECG-Based Field Measurements on Inexperienced Scaffolders. Sensors, 26(3), 949. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030949