A Cross-Layer Framework Integrating RF and OWC with Dynamic Modulation Scheme Selection for 6G Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Existing RF and OWC Technologies

2.1. RF Technologies

2.1.1. Existing

2.1.2. Emerging

2.2. OWC Technologies

2.2.1. Existing

2.2.2. Emerging

3. Key 6G Modulation Schemes

3.1. RF Modulation Schemes

3.1.1. Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM)

3.1.2. Orthogonal Time Frequency Space (OTFS)

3.1.3. Orthogonal Chirp Division Multiplexing (OCDM)

3.1.4. Sparse Code Multiple Access (SCMA)

3.1.5. Index Modulation (IM)

3.2. Optical 6G Modulation Schemes

3.2.1. Optical-OFDM (O-OFDM)

3.2.2. Optical-OTFS (O-OTFS)

3.2.3. Optical-OCDM (O-OCDM)

3.2.4. Optical-SCMA (O-SCMA)

3.2.5. Optical-IM (O-IM)

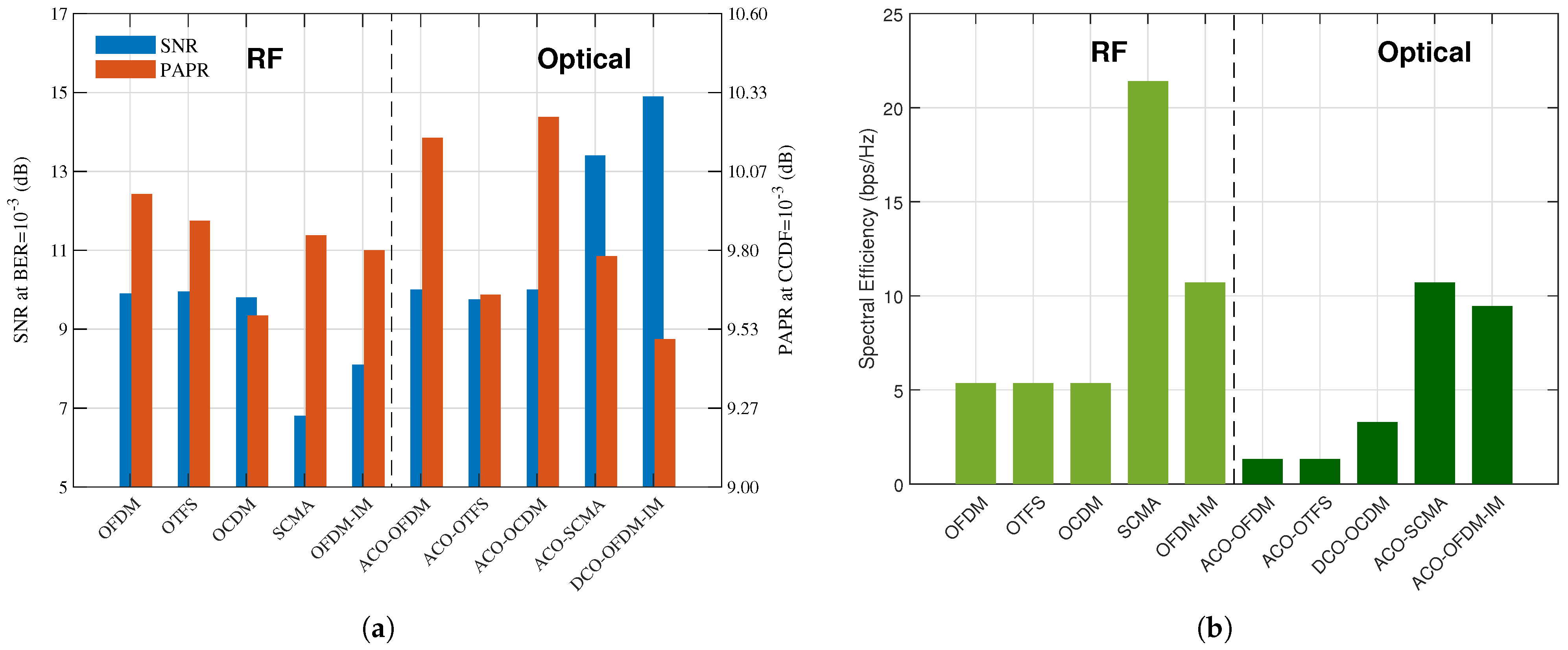

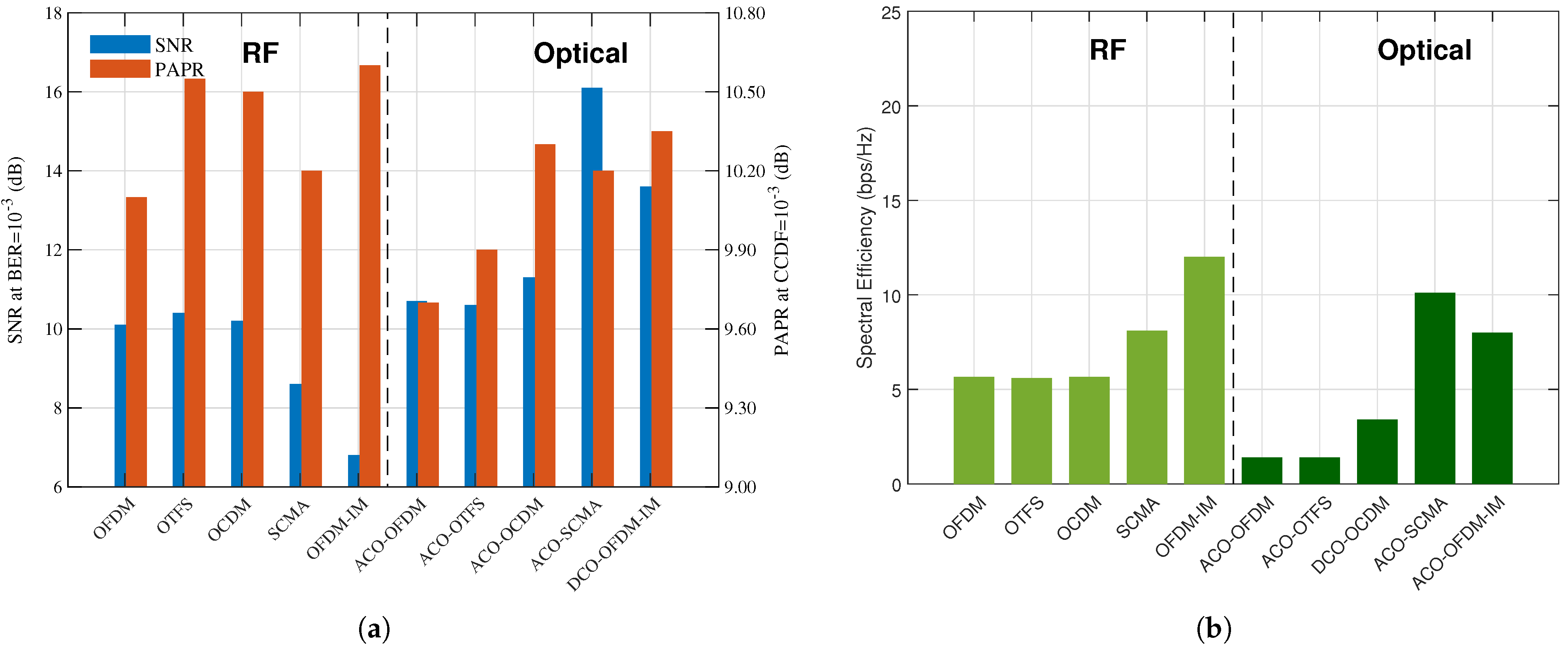

3.3. Performance Comparison

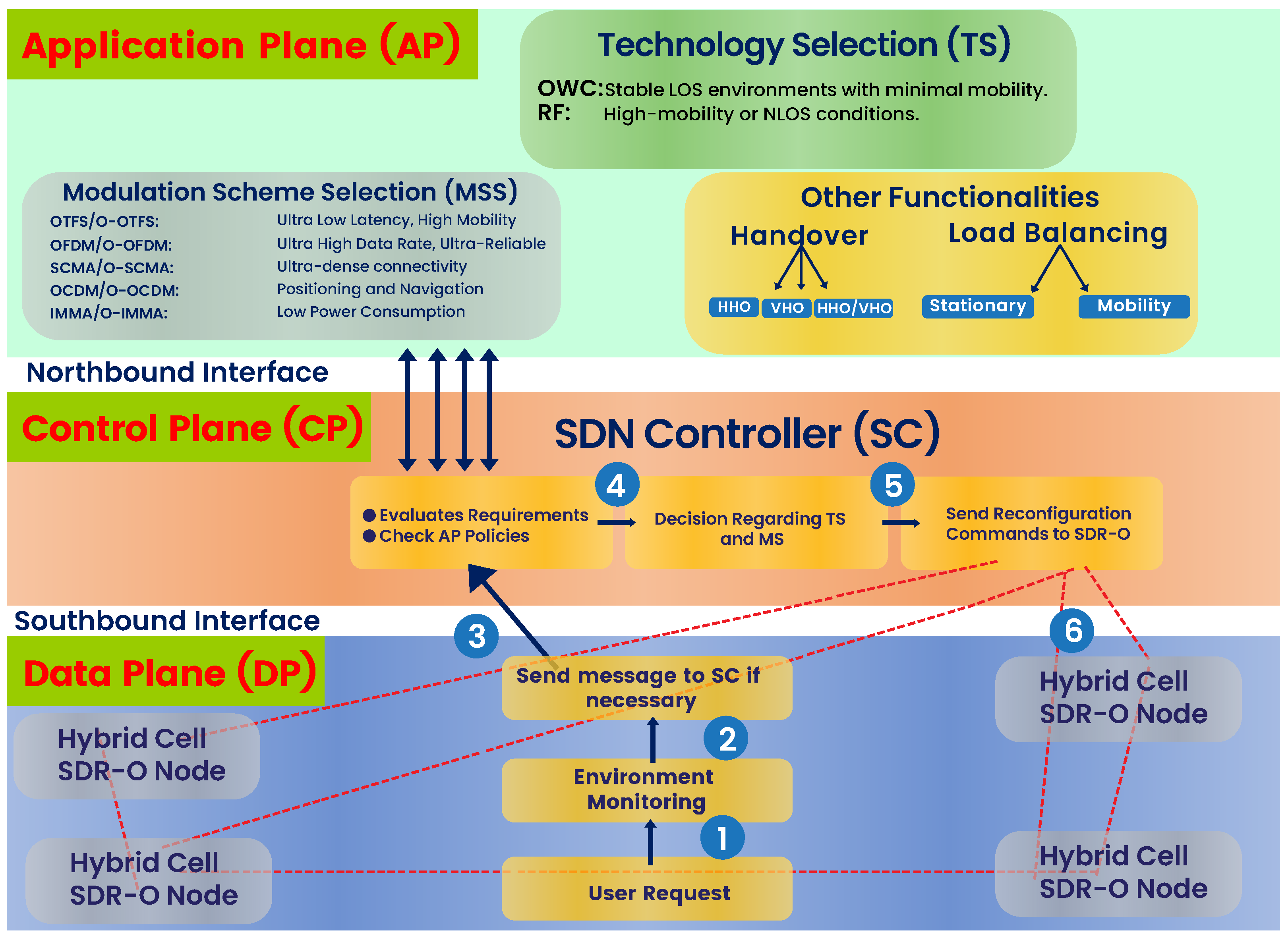

4. Proposed Cross-Layer Hybrid Approach

4.1. Application Layer

- 1.

- Ultra-high data rate.

- 2.

- Ultra-low latency.

- 3.

- Massive connectivity.

- 4.

- High mobility.

- 5.

- High-precision positioning.

- 6.

- Ultra reliability.

- 7.

- Low power consumption/High energy efficiency.

4.2. Network Layer

- Step 1:

- A request is received by the A-Plane from the users or requirements from the applications, such as demands for high-speed communication, low latency, or reliable connectivity.

- Step 2:

- The system actively monitors environment conditions, including LOS, mobility, and network load, to identify the best technology, RF or OWC, in the D-Plane.

- Step 3:

- Based on the environmental monitoring results, the system sends information to the SC in the C-Plane. The SC evaluates the requirements and verifies these with the policies defined in the A-Plane.

- Step 4:

- The SC decides on the appropriate modulation scheme and technology based on the A-Plane to meet the demand from users or applications.

- Step 5:

- Finally, the SC sends the reconfiguration commands to the software-defined radio with optical functionality (SDR-O) node in the D-Plane to implement the setting for efficient and seamless communication.

4.3. Physical Layer

4.4. Decision Metrics and Real-Time Operation

4.4.1. Decision Inputs and Handover Logic

- Channel State Information (CSI): SNR, delay spread, and Doppler shift.

- Link Quality Indicators: BER, packet loss rate, Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI) for RF, and received optical power for OWC.

- Network Load: Traffic volume per link and queueing delay.

- Environmental Conditions: LOS or Non-LOS status (detected via camera/LiDAR sensors for OWC), user mobility speed, and weather data for outdoor OWC links.

- Application KPIs: Latency, throughput, and reliability targets as defined in Table 2.

4.4.2. Latency Bounds for Real-Time Reconfiguration

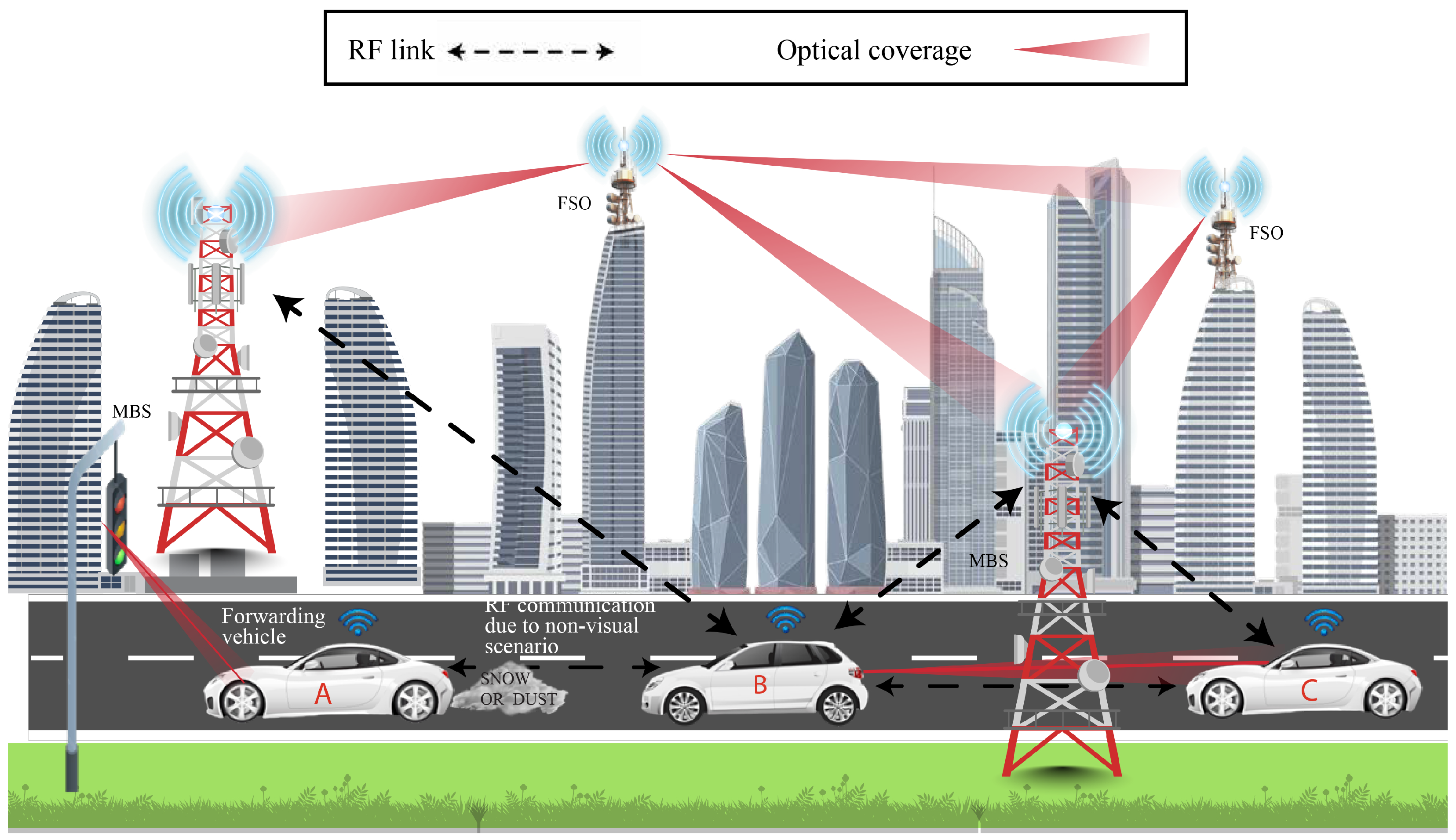

4.5. Illustrative Example of the Proposed Cross-Layer Framework

5. Conclusions and Remaining Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.-X.; You, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Haas, H.; et al. On the Road to 6G: Visions, Requirements, Key Technologies, and Testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts. 2023, 25, 905–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.Z.; Hasan, M.K.; Shahjalal; Hossan, T.; Jang, Y.M. Optical Wireless Hybrid Networks: Trends, Opportunities, Challenges, and Research Directions. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts. 2020, 22, 930–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Soltani, M.D.; Zhou, L.; Safari, M.; Haas, H. Hybrid LiFi and WiFi Networks: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts. 2021, 23, 1398–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tataria, H.; Shafi, M.; Molisch, A.F.; Dohler, M.; Sjöland, H.; Tufvesson, F. 6G Wireless Systems: Vision, Requirements, Challenges, Insights, and Opportunities. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1166–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dat, P.T.; Kanno, A.; Yamamoto, N.; Kawanishi, T. Seamless convergence of fiber and wireless systems for 5G and beyond networks. J. Light. Technol. 2018, 37, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Dias Filgueiras, H.; Saia Lima, E.; Sêda Borsato Cunha, M.; De Souza Lopes, C.H.; De Souza, L.C.; Borges, R.M.; Augusto Melo Pereira, L.; Henrique Brandão, T.; Andrade, T.P.V.; Alexandre, L.C.; et al. Wireless and Optical Convergent Access Technologies Toward 6G. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 9232–9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Ranaweera, C.; Tao, Y.; Nirmalathas, A.; Ediringhe, S.; Wosinska, L.; Song, T. Past and Future Development of Radio-Over-Fiber. J. Light. Technol. 2025, 43, 1525–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, B.G.; Morales Cespedes, M.; Gil Jimenez, V.P.; Garcia Armada, A.; Brandt-Pearce, M. Resource Allocation Exploiting Reflective Surfaces to Minimize the Outage Probability in VLC. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2025, 24, 5493–5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, B.G.; Brandt-Pearce, M. ORIS allocation to minimize the outage probability in a multi-user VLC scenario. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2025, 37, 1463–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, N.; Sugiura, S.; Hanzo, L. 50 Years of Permutation, Spatial and Index Modulation: From Classic RF to Visible Light Communications and Data Storage. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tuts. 2018, 20, 1905–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.; Yang, C.; Wu, G.; Li, S.; Li, G.Y. OFDM and Its Wireless Applications: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2009, 58, 1673–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadani, R.; Rakib, S.; Tsatsanis, M.; Monk, A.; Goldsmith, A.J.; Molisch, A.F.; Calderbank, R. Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation. In IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Zhao, J. Orthogonal Chirp Division Multiplexing. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2016, 64, 3946–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; He, D.; Lin, H.; Li, Y. An Enhanced Multi-User SCMA Codebook Design Over an AWGN Channel. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 1529–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başar, E.; Aygolu, U.; Panayırcı, E.; Poor, H.V. Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing With Index Modulation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2013, 61, 5536–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Mohammady, S. Spread Spectrum OFDM-IM With Efficient Precoded Matrix and Low Complexity Detector. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 192293–192300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, S.D.; Armstrong, J. Comparison of ACO-OFDM, DCO-OFDM and ADO-OFDM in IM/DD Systems. J. Lightw. Technol. 2013, 31, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, X.; Petropoulos, P.; Sugiura, S.; Maunder, R.G.; Yang, L.-L.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Haas, H.; Hanzo, L. Optical OTFS is Capable of Improving the Bandwidth-, Power- and Energy-Efficiency of Optical OFDM. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2024, 72, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, M.I.; Mbulwa, A.I.; Yew, H.T.; Kiring, A.; Chung, S.K.; Farzamnia, A.; Chekima, A.; Haldar, M.K. Handover Decision-Making Algorithm for 5G Heterogeneous Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | (O-)OFDM | (O-)OTFS | (O-)OCDM | (O-)SCMA | (O-)OFDM-IM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Efficiency | Low | Low | Medium | High (Medium) | Medium |

| Power Efficiency | Low | Low | Low | High (Low) | High (Low) |

| Orthogonality | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cyclic Prefix | Yes | Optional | Optional | No | Yes |

| Complexity | Low | High | Medium | High | Medium |

| CFO Resiliency | Low | High | High | Medium | Low |

| Flexibility | High | Medium | Medium | Low | High |

| Support Mobility | Low | High | Medium | Medium | Low |

| Applications | High data rate | High mobility | Positioning and sensing | Massive connectivity | Low power consumption |

| 6G Key Applications | KPI Numbers | Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle-to-vehicle communication, Vehicle-to-infrastructure communication, Automatic drive | 2, 4 | Ultra-low latency: sub-second (<1 ms), High mobility: up to 1000 km/h |

| Ultra-high definition video, Holographic services (Augmented reality, Virtual reality) | 1, 6 | Peak data rate up to 1 Tbps, User experiences: 1–10 Gbps, Reliability: 99.99999% |

| Super dense population (Crowded shopping malls, Football stadiums) | 3 | Massive connection: up to devices/km2 |

| Positioning and navigation, Indoor/Outdoor precise positioning | 5 | Outdoor: meter level, Indoor: centimeter level |

| Internet of bio-nano-things, Healthcare wearables, implantable sensors | 7 | Micro/Nano-watt-level power consumption for passive sensors |

| Process Step | Estimated Timescale | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Environment Reporting | 1–10 ms | Collection of CSI, link quality indicators, and LOS/NLOS status from physical-layer sensors. |

| SDN Controller Decision | 5–20 ms | Policy matching, MSS/TS algorithm execution, and handover decision based on real-time inputs. |

| SDR-O Waveform Switching | <5 ms | Reconfiguration of the RF/optical front-end and modulation parameters in the SDR-O. |

| Total Reconfiguration Latency | ∼10–35 ms | End-to-end latency supports dynamic adaptation for 6G applications with latency budgets ≥ 50 ms. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Waheed, A.; Genoves Guzman, B.; Mohammady, S.; Brandt-Pearce, M. A Cross-Layer Framework Integrating RF and OWC with Dynamic Modulation Scheme Selection for 6G Networks. Sensors 2026, 26, 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030926

Waheed A, Genoves Guzman B, Mohammady S, Brandt-Pearce M. A Cross-Layer Framework Integrating RF and OWC with Dynamic Modulation Scheme Selection for 6G Networks. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):926. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030926

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaheed, Ahmed, Borja Genoves Guzman, Somayeh Mohammady, and Maite Brandt-Pearce. 2026. "A Cross-Layer Framework Integrating RF and OWC with Dynamic Modulation Scheme Selection for 6G Networks" Sensors 26, no. 3: 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030926

APA StyleWaheed, A., Genoves Guzman, B., Mohammady, S., & Brandt-Pearce, M. (2026). A Cross-Layer Framework Integrating RF and OWC with Dynamic Modulation Scheme Selection for 6G Networks. Sensors, 26(3), 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030926