Precision Farming with Smart Sensors: Current State, Challenges and Future Outlook

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search Methodology

3. Role of Sensors and Smart Sensor Technologies in Precision Farming

3.1. Role of Smart Sensors in Agriculture

3.1.1. Real-Time Data Acquisition and Analysis

3.1.2. Integration with IoT and WSN Technologies

3.1.3. Addressing Unstructured Environments

3.1.4. Handling Biological Variability

3.2. Transformative Landscape of Precision Farming Through Advanced Sensor Technologies

3.2.1. Soil Monitoring for Optimized Resource Management

3.2.2. Crop Health Monitoring and Plant Wearables

3.2.3. Weather and Environmental Monitoring

3.2.4. Livestock Monitoring

3.2.5. Sensor-Based Disease Detection

3.2.6. Automated Irrigation Systems

3.2.7. Predictive Analysis and Decision Support

4. Sensors Used in Agriculture and Their Performance Limitations

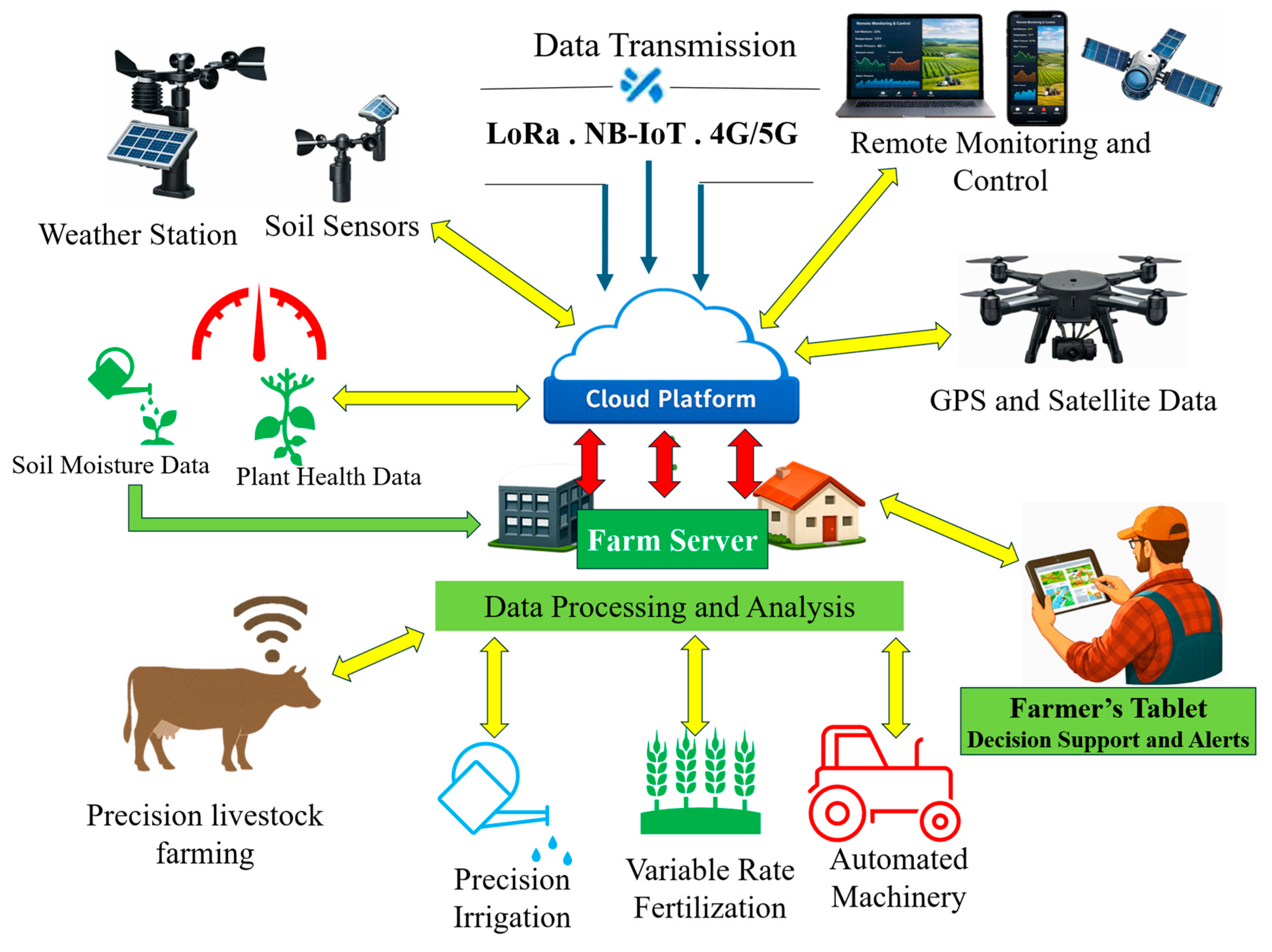

4.1. Internet of Things (IoT) Platforms

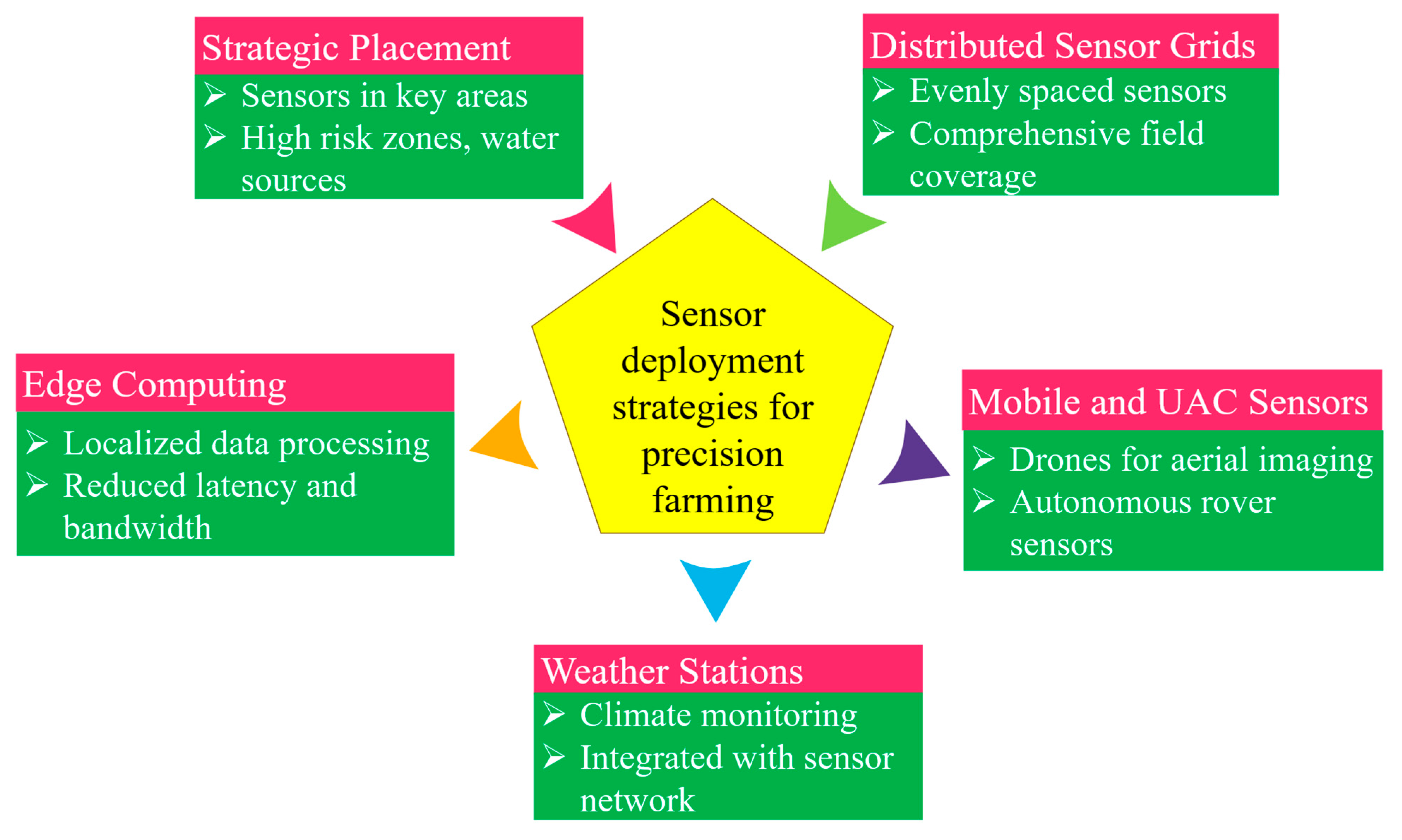

4.2. Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs)

4.3. Remote Sensing

4.4. Robotics and Automation

4.5. Decision Support Systems (DSS)

4.6. Multi-Sensor Fusion

4.7. Comparison of Sensing Approaches and Their Suitability in Real Field Conditions

5. Algorithm and Model Mechanisms Behind Sensor Decision Making in Agriculture

5.1. Algorithms for Intelligent Decision Making

5.1.1. Machine Learning Algorithms

5.1.2. Fuzzy Logic Systems

5.1.3. Deep Learning Models

5.1.4. Other Intelligent Decision-Making Algorithms

5.2. Model Mechanisms for Intelligent Sensors

5.2.1. Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN) and IoT

5.2.2. Edge Computing

5.2.3. Data Fusion and Analysis

5.2.4. Intelligent Sensors and Measuring Instruments

5.2.5. Intelligent Decision-Making Systems in Agriculture

6. Integrated Sensor Systems and Data Analytics for Environmental Monitoring and Sustainability

6.1. Sensor Data Value Chain and Agricultural Knowledge Discovery

6.1.1. Data Collection

6.1.2. Data Processing and Analysis

6.2. Impact on Environmental Monitoring and Sustainability

7. Challenges and Limitations of Sensors in Agriculture

7.1. Sensor Drift

7.2. Calibration Problems

7.3. Harsh Environmental Conditions and Sensor Robustness

7.4. Network Connectivity and Data Management Issues

7.5. AI Models Struggling with Noisy Agricultural Data

7.6. High Initial Investment and Cost Barriers

7.7. Energy Constraints

7.8. Technical Expertise and Data Security

7.9. Lack of Standardization and Interoperability

7.10. Specific Sensor Limitations

8. Global Trends in Agricultural Sensor Adoption

8.1. Market Valuation and Projections

8.2. Regional Adoption Rates and Market Penetration

8.2.1. North America

8.2.2. Europe

8.2.3. Asia-Pacific

8.2.4. Africa

8.2.5. Latin America

9. Future Trends, Research Gaps and Sustainability of Sensor Use in Agriculture

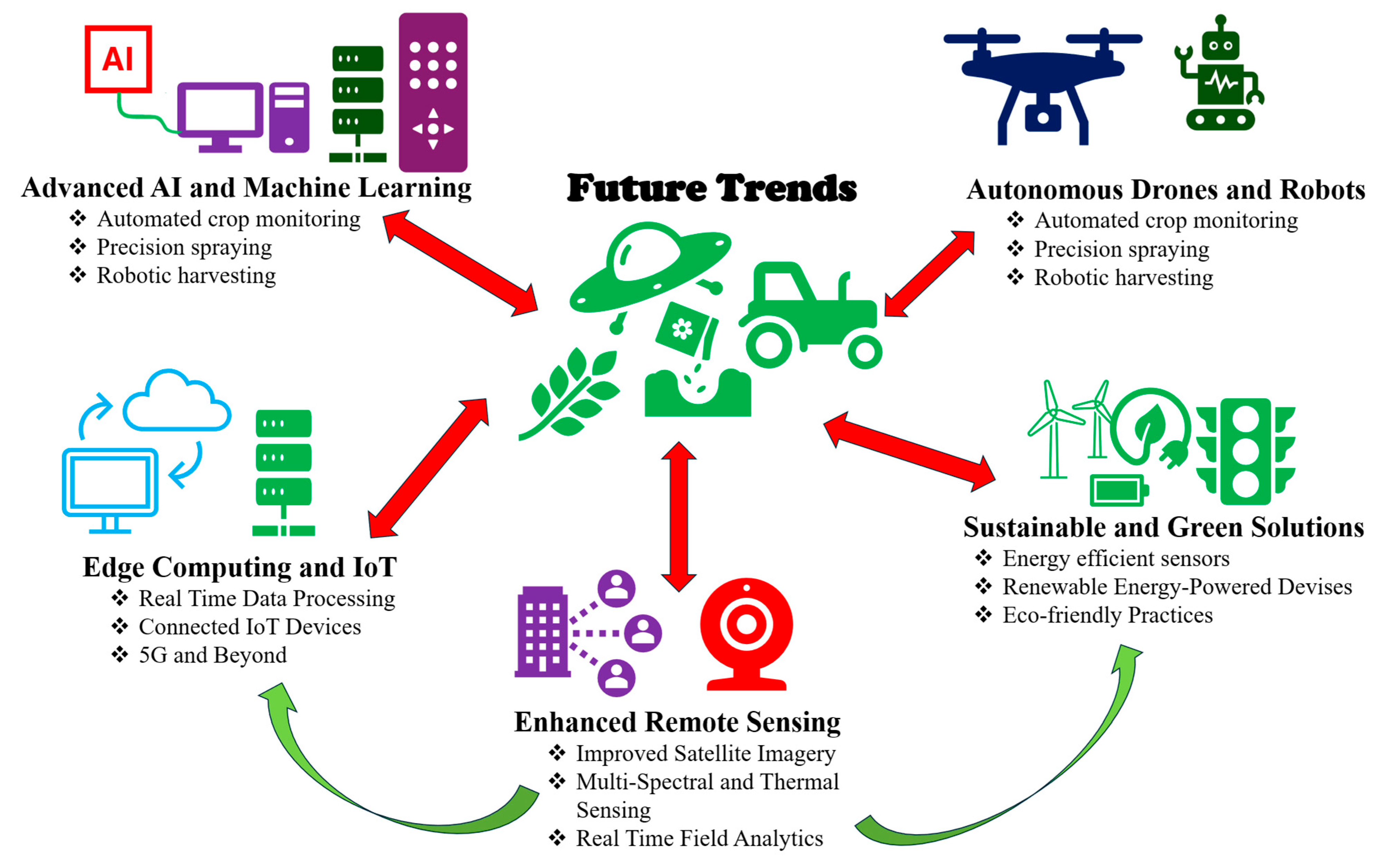

9.1. Future Trends of Sensor Use in Agriculture

9.2. Specific Sensor Advancements and Applications

9.2.1. Next-Generation Sensor Materials

9.2.2. Autonomous Sensor Networks and Robotics

9.2.3. Advanced Data Analytics and AI Integration

9.3. Research Gaps in Sensor Use in Agriculture

9.4. Sustainability Aspects of Sensor Deployment

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CWSI | Crop Water Stress Index |

| DSS | Decision Support Systems |

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| HCAI | Human-Centered AI |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MSF | Multi-Server Fusion |

| NEMS | Nano-Electro-Mechanical Systems |

| NEN | Nearest Neighbor |

| PC | Personal Computer |

| PLF | Precision Livestock Farming |

| RoI | Return on Investment |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| UAS | Unmanned Aerial Systems |

| VRT | Variable Rate Technologies |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Networks |

References

- Hemathilake, D.M.; Gunathilake, D.M. Agricultural productivity and food supply to meet increased demands. In Future Foods; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manono, B.O.; Moller, H.; Benge, J.; Carey, P.; Lucock, D.; Manhire, J. Assessment of soil properties and earthworms in organic and conventional farming systems after seven years of dairy farm conversions in New Zealand. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 43, 678–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, S.; Farhana, A. Smart agriculture: The future of agriculture using AI and IoT. J. Comput. Sci. 2021, 17, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, S.; Iqbal, S.; Popescu, S.M.; Kim, S.L.; Chung, Y.S.; Baek, J.H. Integration of smart sensors and IOT in precision agriculture: Trends, challenges and future prospectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1587869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anap, V.N.; Gaikar, P.S.; Jadhav, R.M.; Lohale, S.H. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Prospects. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2025, 31, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, V.H.; Eze, E.C.; Alaneme, G.U.; BUBU, P.E.; Nnadi, E.O.; Okon, M.B. Integrating IoT sensors and machine learning for sustainable precision agroecology: Enhancing crop resilience and resource efficiency through data-driven strategies, challenges, and future prospects. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, P.; Singh, P.K.; Rana, A.K. “Precision Agriculture Farming” Enhancing Farming Efficiency through Technology Integration. In Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Networking (ICAC2N), Greater Noida, India, 16–17 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ansary, D.O. Smart Farming and Orchard Management: Insights and Innovations. Curr. Food Sci. Technol. Rep. 2025, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternas, I.; Velásquez, I.; Caro, A.; Rodríguez, A. Systematic literature review of implementations of precision agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Kumar, A. Advances in Soil and Plant Nutrient Management of Potatoes. In Advances in Research on Potato Production; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Babar, M.A. Innovations in precision agriculture and smart farming: Emerging technologies driving agricultural transformation. Innov. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 11, 2430004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Santos, S.; Gonçalves, P. Precision agriculture for crop and livestock farming—Brief review. Animals 2021, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.; Saini, R.K. Energy-saving sensors for precision agriculture in Wireless Sensor Network: A review. In Proceedings of the 2019 Women Institute of Technology Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (WITCON ECE), Dehradun, India, 22–23 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Singh, L.P.; Gupta, A.; Lohan, S.K. Advancements in smart farming: A comprehensive review of IoT, wireless communication, sensors, and hardware for agricultural automation. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 362, 114605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.; Arduini, S.; Uyar, H.; Psiroukis, V.; Kasimati, A.; Fountas, S. Economic and environmental benefits of digital agricultural technologies in crop production: A review. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mešić, A.; Jurić, M.; Donsì, F.; Maslov Bandić, L.; Jurić, S. Advancing climate resilience: Technological innovations in plant-based, alternative and sustainable food production systems. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgendi, G. Unlocking the potential of precision agriculture for sustainable farming. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finco, A.; Bucci, G.; Belletti, M.; Bentivoglio, D. The economic results of investing in precision agriculture in durum wheat production: A case study in central Italy. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, R.; Singh, K.; Upadhyaya, Y.R.; Sharma, A.K.; Brym, Z.; Sharma, L.K.; Singh, H. Estimating plant height, nitrogen uptake and above-ground biomass using UAV multispectral imaging coupled with machine learning in industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 237, 122130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mana, A.A.; Allouhi, A.; Hamrani, A.; Rehman, S.; El Jamaoui, I.; Jayachandran, K. Sustainable AI-based production agriculture: Exploring AI applications and implications in agricultural practices. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 7, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, S.; Kefale, H.; Gelaye, Y. Application of precision agriculture technologies for sustainable crop production and environmental sustainability: A systematic review. Sci. World J. 2024, 2024, 2126734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Mourik, S.; van der Tol, R.; Linker, R.; Reyes-Lastiri, D.; Kootstra, G.; Koerkamp, P.G.; van Henten, E.J. Introductory overview: Systems and control methods for operational management support in agricultural production systems. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 139, 105031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, Y.S.; Brindal, M. A meta-analysis of factors driving the adoption of precision agriculture. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundal, G.S.; Laux, C.M.; Buckmaster, D.; Sutton, M.J.; Langemeier, M. Exploring barriers to the adoption of internet of things-based precision agriculture practices. Agriculture 2023, 13, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, E.F.; Appadurai, M.; Athiappan, K. Precision farming in modern agriculture. In Smart Agriculture Automation Using Advanced Technologies: Data Analytics and Machine Learning, Cloud Architecture, Automation and IoT; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.A.; El-Ramady, H.; Jalhoum, M.; Gad, A.; Mohamed, E.S. Precision farming technologies to increase soil and crop productivity. In Agro-Environmental Sustainability in MENA Regions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 117–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretas, I.L.; Dubeux, J.C., Jr.; Cruz, P.J.; Oduor, K.T.; Queiroz, L.D.; Valente, D.S.; Chizzotti, F.H. Precision livestock farming applied to grazingland monitoring and management—A review. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 1164–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Cárdenas, P.; Diezma, B.; San Miguel, G.; Valero, C.; Correa, E.C. Environmental LCA of precision agriculture for stone fruit production. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Mikiciuk, G.; Durlik, I.; Mikiciuk, M.; Łobodzińska, A.; Śnieg, M. The IoT and AI in Agriculture: The Time Is Now—A Systematic Review of Smart Sensing Technologies. Sensors 2025, 25, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, U.; Mumtaz, R.; García-Nieto, J.; Hassan, S.A.; Zaidi, S.A.; Iqbal, N. Precision agriculture techniques and practices: From considerations to applications. Sensors 2019, 19, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Mishra, R.; Gupta, H.P.; Dutta, T. Smart sensing for agriculture: Applications, advancements, and challenges. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2021, 10, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, P.; Kaur, G. Smart sensors for smart agriculture. In Artificial Intelligence and IoT-Based Technologies for Sustainable Farming and Smart Agriculture; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, F.K.; Anyebe, O.; Tanko, F.; Abdulkadir, A.; Manono, B.O.; Matsika, T.A.; Abubakar, F.; Bello, S.K. Conservation agriculture for sustainable soil health management: A review of impacts, benefits and future directions. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.P.; Song, H.; Sikdar, B.; Dutta, T.; Faigl, J. Guest Editorial Special Issue on Smart Sensing for Agriculture. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 17419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifna, N.F.; Thaiyalnayaki, S. A Smart Survey Analysis using Wireless Sensor Networks in Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2024 11th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 28 February–1 March 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreldin, N.; Cheng, X.; Youssef, A. An Overview of Software Sensor Applications in Biosystem Monitoring and Control. Sensors 2024, 24, 6738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Shaikh, F.K. Wireless sensor network–based smart agriculture. In Opportunistic Networking; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Sharma, S.K.; Parashar, A. Smart agriculture using wireless sensor networks. In Integration of WSNs into Internet of Things; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowla, M.N.; Mowla, N.; Shah, A.S.; Rabie, K.M.; Shongwe, T. Internet of Things and wireless sensor networks for smart agriculture applications: A survey. IEEe Access 2023, 11, 145813–145852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarif, K.O.M.; Alam, A.; Hotak, Y. Smart sensor technologies shaping the future of precision agriculture: Recent advances and future outlooks. J. Sens. 2025, 2025, 2460098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manono, B.O. Effects of Salinity on Seed Germination: Mechanisms, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies. Seeds 2026, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, S.B.; Tsourdos, A.; Zbikowski, R.; White, B.A. Unstructured environmental mapping using low cost sensors. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control, Sanya, China, 6–8 April 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1080–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, Z.K.; Saguna, S.; Åhlund, C. Correction: Detecting Anomalies in Daily Activity Routines of Older Persons in Single Resident Smart Homes: Proof-of-Concept Study. JMIR Aging 2024, 7, e58394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolski, S.; Macek, K.; Ferguson, D.; Siegwart, R. SMART Navigation in Structured and Unstructured Environments. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Beijing, China, 9–15 October 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; p. 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Boubin, J.; Gafurov, D.; Zhou, J.; Aloysius, N.; Nguyen, H.; Calyam, P. Uav swarms in smart agriculture: Experiences and opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 18th International Conference on e-Science (e-Science), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 11–14 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, A.; Heredia, S.; Windle, A.E.; Tovar-Sánchez, A.; Navarro, G. Enhancing georeferencing and mosaicking techniques over water surfaces with high-resolution unmanned aerial vehicle (uav) imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrettino, D. Sensor Systems for Smart Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 13th Latin America Symposium on Circuits and System (LASCAS), Santiago, Chile, 1–4 March 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Bhargava, K.; Donnelly, W. Precision farming: Sensor analytics. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2015, 30, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, E.M.; Le, A.T.; Heo, S.; Chung, Y.S.; Mansoor, S. The path to smart farming: Innovations and opportunities in precision agriculture. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Cao, Y.; Marelli, B.; Zeng, X.; Mason, A.J.; Cao, C. Soil sensors and plant wearables for smart and precision agriculture. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thingujam, U.; Prabha, D.; Ghosh Bag, A.; Thingujam, V.; Darshan, N.P.; Dutta, S.; Gorain, S. From point sensing to intelligent systems: A comprehensive review on advanced sensor technologies for soil health monitoring. Discov. Sens. 2025, 1, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biney, J.K.; Houška, J.; Kachalova, O.; Volánek, J.; Agyeman, P.C.; Abebrese, D.K.; Azizabadi, E.C.; Badreldin, N. Significance of Planet SuperDove and refined Sentinel-2 imagery fusion for enhanced soil organic carbon prediction in croplands. Catena 2025, 254, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathne, N.N.; Bakar, M.S.; Abas, P.E.; Yassin, H. A cloud enabled crop recommendation platform for machine learning-driven precision farming. Sensors 2022, 22, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagu, R.; Golenev, S.; Werner, L.; Berner, C.; Gilles, R.; Revay, Z.; Ziegele, L.; Plomp, J.; Märkisch, B.; Gernhäuser, R. 4D Tomography for neutron depth profiling applications. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2024, 1065, 169543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Yang, F.; Huang, S.; Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, M.; Yao, H.; Li, J.; Ma, J. An Autonomous pH Sensor for Real-Time High-Frequency Monitoring of Ocean Acidification in Estuarine and Coastal Areas. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 27113–27121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Jorquera, C.; Orozco, J.; Baldi, A. ISFET based microsensors for environmental monitoring. Sensors 2009, 10, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Park, J.H. Monitoring of soil EC for the prediction of soil nutrient regime under different soil water and organic matter contents. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-García, P.E.; Rivera, A.E.; Rivera-González, G.; Tovar, L.C. Digitalization-based nutrient management to achieve both food security and environmental sustainability. In Point Source Nitrogen Pollution; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Bijjahalli, S.; Fahey, T.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R.; Lamb, D.W. Destructive and non-destructive measurement approaches and the application of AI models in precision agriculture: A review. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 1127–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, X.; Shi, Q.; He, T.; Sun, Z.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Sulaiman, O.B.; Dong, B.; Lee, C. Development trends and perspectives of future sensors and MEMS/NEMS. Micromachines 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, E.E.; Anggraini, L.; Kumi, J.A.; Karolina, L.B.; Akansah, E.; Sulyman, H.A.; Mendonça, I.; Aritsugi, M. IoT solutions with artificial intelligence technologies for precision agriculture: Definitions, applications, challenges, and opportunities. Electronics 2024, 13, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, D.; Mohanty, S.; Das, S.; Senapaty, J.; Sahoo, D.B.; Mishra, B.; Baig, M.J.; Behera, L. From spectrum to yield: Advances in crop photosynthesis with hyperspectral imaging. Photosynthetica 2025, 63, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of remote sensing in precision agriculture: A review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.I.; Wang, G.; Khan, S.N.; Song, C.; Ma, C.; Zhang, X.; Lan, Y. Multi-Dimensional Optical Remote Sensing in Agriculture: Spectral, Angular, and Spatial Scaling for Crop Stress Monitoring. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Yadav, M.; Barak, D.; Bansal, S.; Moreira, F. Machine-Learning-Based Frameworks for Reliable and Sustainable Crop Forecasting. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.G.; Oduor, P.; Igathinathane, C.; Howatt, K.; Sun, X. A systematic review of hyperspectral imaging in precision agriculture: Analysis of its current state and future prospects. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 222, 109037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smigaj, M.; Agarwal, A.; Bartholomeus, H.; Decuyper, M.; Elsherif, A.; de Jonge, A.; Kooistra, L. Thermal infrared remote sensing of stress responses in forest environments: A review of developments, challenges, and opportunities. Curr. For. Rep. 2024, 10, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Li, W.; Cheema, M.J.; Zaman, Q.U.; Shaheen, A.; Aslam, B.; Zhu, W.; Ajmal, M.; Faheem, M.; Hussain, S.; et al. UAV-based remote sensing in plant stress imagine using high-resolution thermal sensor for digital agriculture practices: A meta-review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 1135–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, S.; Zand-Parsa, S.; Niyogi, D. Assessing crop water stress index of citrus using in-situ measurements, landsat, and sentinel-2 data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 1893–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Li, M.Z.; Li, J.Y.; Gao, Y.Y.; Liu, C.R.; Hao, G.F. Wearable sensor supports in-situ and continuous monitoring of plant health in precision agriculture era. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 1516–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthumalai, K.; Gokila, N.; Haldorai, Y.; Rajendra Kumar, R.T. Advanced wearable sensing technologies for sustainable precision agriculture–a review on chemical sensors. Adv. Sens. Res. 2024, 3, 2300107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Wei, Q.; Zhu, Y. Emerging wearable sensors for plant health monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2106475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kong, J.; Wu, D.; Guan, Z.; Ding, B.; Chen, F. Wearable sensor: An emerging data collection tool for plant phenotyping. Plant Phenomics 2023, 5, 0051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.H.; Cukurtepe, H. EnviroSense: AI-Driven Microclimate Control for Sustainable Agriculture Using Edge Computing. In Intelligent Computing-Proceedings of the Computing Conference; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Awais, M.; Ru, W.; Shi, W.; Ajmal, M.; Uddin, S.; Liu, C. Review of sensor network-based irrigation systems using IoT and remote sensing. Adv. Meteorol. 2020, 2020, 8396164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.; Marquez, M.; Arguello, H. Super-Resolution in Compressive Coded Imaging Systems via l2–l1–l2 Minimization Under a Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 Data Compression Conference (DCC), Virtual, 24–27 March 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, A.P.; Al-Humairi, S.N. The impact of iot and sensor integration on real-time weather monitoring systems: A systematic review. Res. Sq. 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niloofar, P.; Francis, D.P.; Lazarova-Molnar, S.; Vulpe, A.; Vochin, M.C.; Suciu, G.; Balanescu, M.; Anestis, V.; Bartzanas, T. Data-driven decision support in livestock farming for improved animal health, welfare and greenhouse gas emissions: Overview and challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 190, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanna, M.; Bovo, M.; Cavallini, D. Wearable collar technologies for dairy cows: A systematized review of the current applications and future innovations in precision livestock farming. Animals 2025, 15, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhilta, A.; Jadhav, K.; Singh, R.; Negi, S.; Sharma, N.; Verma, R.K. Advanced Precision Veterinary Technologies and Smart Boluses: Innovations in Drug Delivery, Health Monitoring, and Future Perspectives. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 115, 107563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafer, M.T.; Sikalu, T.C. Smart Biosensor-Based Health Monitoring System for Early Disease Detection in Livestock. Natl. J. Anim. Health Sustain. Livest. 2025, 3, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Compte, A.; Yan, Y.; Cortés, X.; Escalera, S.; Jacques-Junior, J.C. Housed pig identification and tracking for precision livestock farming. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 293, 128466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpiyabovorn, O.; Wang, T.; Menendez, H.; Yago, A.L. Precision Livestock Farming Technologies in Beef Cattle Production: Current and Future. Choices 2025, 40, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buja, I.; Sabella, E.; Monteduro, A.G.; Chiriacò, M.S.; De Bellis, L.; Luvisi, A.; Maruccio, G. Advances in plant disease detection and monitoring: From traditional assays to in-field diagnostics. Sensors 2021, 21, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Palma, L.; Belli, A.; Sabbatini, L.; Pierleoni, P. Recent advances in internet of things solutions for early warning systems: A review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubero, J.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Cuesta-Morrondo, S.; Palacio-Bielsa, A.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Sabuquillo, P.; Poblete, T.; Landa, B.B.; Garita-Cambronero, J. New approaches to plant pathogen detection and disease diagnosis. Phytopathology 2024, 14, 1989–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyussembayev, K.; Sambasivam, P.; Bar, I.; Brownlie, J.C.; Shiddiky, M.J.; Ford, R. Biosensor technologies for early detection and quantification of plant pathogens. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 636245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avola, G.; Matese, A.; Riggi, E. An overview of the special issue on “precision agriculture using hyperspectral images”. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champness, M.; Vial, L.; Ballester, C.; Hornbuckle, J. Evaluating the performance and opportunity cost of a smart-sensed automated irrigation system for water-saving rice cultivation in temperate Australia. Agriculture 2023, 13, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoneim, A.A.; Kimaita, H.N.; Al Kalaany, C.M.; Derardja, B.; Dragonetti, G.; Khadra, R. IoT sensing for advanced irrigation management: A systematic review of trends, challenges, and future prospects. Sensors 2025, 25, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahane, A.; Kechar, B.; Meddah, Y.; Benabdellah, O. Automated irrigation management platform using a wireless sensor network. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth International Conference on Internet of Things: Systems, Management and Security (IOTSMS), Granada, Spain, 22–25 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.B.; Kulkarni, R.B.; Patil, S.S.; Kharade, P.A. Machine learning based precision agriculture model for farm irrigation to optimize water usage. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; Volume 1285, p. 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoneim, A.A.; Al Kalaany, C.M.; Dragonetti, G.; Derardja, B.; Khadra, R. Comparative analysis of soil moisture-and weather-based irrigation scheduling for drip-irrigated lettuce using low-cost Internet of Things capacitive sensors. Sensors 2025, 25, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Hussain, T.; Zahid, A. Smart irrigation technologies and prospects for enhancing water use efficiency for sustainable agriculture. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, T.; Neményi, M.; Nyéki, A. Applying IoT sensors and big data to improve precision crop production: A review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elashmawy, R.; Uysal, I. Precision agriculture using soil sensor driven machine learning for smart strawberry production. Sensors 2023, 23, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SS, V.C.; Hareendran, A.; Albaaji, G.F. Precision farming for sustainability: An agricultural intelligence model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadporozhskaya, M.; Kovsh, N.; Paolesse, R.; Lvova, L. Recent advances in chemical sensors for soil analysis: A review. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Halder, N.; Singh, B.; Singh, J.; Sharma, S.; Shacham-Diamand, Y. Smart farming revolution: Portable and real-time soil nitrogen and phosphorus monitoring for sustainable agriculture. Sensors 2023, 23, 5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toselli, M.; Baldi, E.; Ferro, F.; Rossi, S.; Cillis, D. Smart farming tool for monitoring nutrients in soil and plants for precise fertilization. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, W.; Van Gorsel, E.; Hughes, D.; Suarez, L.; Jimenez-Berni, J.; Held, A. THEMS: An automated thermal and hyperspectral proximal sensing system for canopy reflectance, radiance and temperature. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, M.; Barón, M.; Pérez-Bueno, M.L. Thermal imaging for plant stress detection and phenotyping. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yu, S.; Ju, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, D. Multi-scale remote-sensing phenomics integrated with multi-omics: Advances in crop drought–heat stress tolerance mechanisms and perspectives for climate-smart agriculture. Plants 2025, 14, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Ponce, P.; Mata, O.; Molina, A.; Meier, A. Local weather station design and development for cost-effective environmental monitoring and real-time data sharing. Sensors 2023, 23, 9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, A. Internet of things for environmental sustainability and climate change. In Internet of Things for Sustainable Community Development: Wireless Communications, Sensing, and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 33–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.Y.; Leong, Y.Z.; San Leong, W. Poultry precision: Exploring the impact of IoT sensors on smart farming practices. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Electromagnetics: Applications and Student Innovation Competition (iWEM), Taoyuan, Taiwan, 10–12 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.; Croce, D.; Tinnirello, I.; Vitale, G. A survey on LoRa for smart agriculture: Current trends and future perspectives. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 3664–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.C.; Gomes, N.O.; Calegaro, M.L.; Machado, S.A.; de Oliveira, T.V.; Soares, N.D.; Raymundo-Pereira, P.A. Sustainable plant-wearable sensors for on-site, rapid decentralized detection of pesticides toward precision agriculture and food safety. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 155, 213676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.C.; Sun, X.Y.; Sun, W.X.; Cao, L.X.; Wang, X.Q.; He, Z.Z. Flexible wearables for plants. Small 2021, 17, 2104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Zarei, M.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.G. Wearable Standalone Sensing Systems for Smart Agriculture. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2414748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remya, S.; Anjali, T.; Abhishek, S. The power of vision transformers and acoustic sensors for cotton pest detection. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2024, 5, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Channi, H.K.; Banga, H.K. Data analytics in agriculture: Predictive models and real-time decision-making. In Smart Agritech: Robotics, AI, and Internet of Things (IoT) in Agriculture; Wiley-Scrivener: Beverly, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.J. Artificial Intelligence Analysis for Crop Survival Prediction in Smart Agriculture. Smart Media J. 2025, 14, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekiek, S.; Jebari, H.; Ezziyyani, M.; Cherrat, L. AI-Driven Pest Control and Disease Detection in Smart Farming Systems. In International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Development; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Si, Y.; Fu, Y.; An, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Y. Exploration of the Plant World: Application and Innovation of Plant-Wearable Sensors for Real-Time Detection. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhika, V.; Ramya, R.; Abhishek, R. Machine learning approach-based plant disease detection and pest detection system. In International Conference on Communications and Cyber Physical Engineering; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2018; Volume 2023, pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monica, M.; Yeshika, B.; Abhishek, G.S.; Sanjay, H.A.; Dasiga, S. IoT based control and automation of smart irrigation system: An automated irrigation system using sensors, GSM, Bluetooth and cloud technology. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Recent Innovations in Signal Processing and Embedded Systems (RISE), Bhopal, India, 27–29 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher, A.; Hamwiz, H.; Almas, A.; Al-Baitamouni, S.; Al-Bathal, M. Automated smart solar irrigation system. In Smart Cities Symposium 2018; IET: Stevenage, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omia, E.; Bae, H.; Park, E.; Kim, M.S.; Baek, I.; Kabenge, I.; Cho, B.K. Remote sensing in field crop monitoring: A comprehensive review of sensor systems, data analyses and recent advances. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullo, S.L.; Sinha, G.R. Advances in IoT and smart sensors for remote sensing and agriculture applications. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamara, N.; Islam, M.D.; Bai, G.F.; Shi, Y.; Ge, Y. Ag-IoT for crop and environment monitoring: Past, present, and future. Agric. Syst. 2022, 203, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaddoost, A.; Ogodo, E.; Prasai, S. Enhanced data transmission platform in smart farms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Omni-Layer Intelligent Systems, Crete, Greece, 5 May 2019; pp. 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.; Kumar, M.S.; Dhannia, T. A study on the significance of smart IoT sensors and Data science in Digital agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2020 Advanced Computing and Communication Technologies for High Performance Applications (ACCTHPA), Cochin, India, 2–4 July 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, H.; Naeem, M.; Iqbal, M.; Aqeel, M.; Ullah, S.S. IoT-driven smart agricultural technology for real-time soil and crop optimization. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Govindaraj, R.; Amesho, K.T.; Shangdiar, S.; Kadhila, T.; Iikela, S. Smart Agriculture Using IoT for Automated Irrigation, Water and Energy Efficiency. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguma, A.L.; Bai, X. How the internet of things technology improves agricultural efficiency. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 58, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logeshwaran, J.; Srivastava, D.; Kumar, K.S.; Rex, M.J.; Al-Rasheed, A.; Getahun, M.; Soufiene, B.O. Improving crop production using an agro-deep learning framework in precision agriculture. BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manono, B.O. Small-Scale Farming in the United States: Challenges and Pathways to Enhanced Productivity and Profitability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwuanyi, S.; Irvine, J. Security analysis of IoT networks and platforms. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Networks, Computers and Communications (ISNCC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 16–18 June 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiang, J.; Jin, Y.; Liu, R.; Yan, J.; Wang, L. Boost precision agriculture with unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing and edge intelligence: A survey. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyrianoff, I.; Heideker, A.; Silva, D.; Kamienski, C. Scalability of an Internet of Things platform for smart water management for agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2018 23rd conference of open innovations association (FRUCT), Bologna, Italy, 13–16 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, M.O.; Adami, D.; Giordano, S. Network performance evaluation of a LoRa-based IoT system for crop protection against ungulates. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 25th International Workshop on Computer Aided Modeling and Design of Communication Links and Networks (CAMAD), Virtual, 14–16 September 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, A.; Rejeb, K.; Rejeb, A.; Mostafa, M.M.; Zailani, S. Wireless sensor networks in agriculture: Insights from bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.A.; Jian, X.U.; Juanjuan, S.H.; Ruonan, S.U. Research and Application of Wireless Sensor Networks in Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Electronic Industry and Automation (EIA 2017), Suzhou, China, 23–25 June 2017; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, K.H.; Sasloglou, K.; Goh, H.G.; Wu, T.T.; Stephen, B.; Gilroy, M.; Tachtatzis, C.; Glover, I.A.; Michie, C.; Andonovic, I. Adaptation of wireless sensor network for farming industries. In Proceedings of the 2009 Sixth International Conference on Networked Sensing Systems (INSS), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 17–19 June 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balendonck, J.; Hemming, J.; Tuijl, B.V.; Incrocci, L.; Pardossi, A.; Marzialetti, P. Sensors and Wireless Sensor Networks for Irrigation Management Under Deficit Conditions (FLOW-AID). OP-1985. 2008. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/24858 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Bencini, L.; Chiti, F.; Collodi, G.; Di Palma, D.; Fantacci, R.; Manes, A.; Manes, G. Agricultural monitoring based on wireless sensor network technology: Real long life deployments for physiology and pathogens control. In Proceedings of the 2009 Third International Conference on Sensor Technologies and Applications, Athens/Glyfada, Greece, 18–23 June 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, K.; Reddy, G.S.; Makala, R.; Srihari, T.; Sharma, N.; Singh, C. Studies on energy efficient techniques for agricultural monitoring by wireless sensor networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 113, 109052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, B.; Fisher, J.B.; Piechota, T.; Hassani, M.; Suardiaz, D.C.; Puri, R.; Cahill, J.; Atamian, H.S. Satellite observations indicate that chia uses less water than other crops in warm climates. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Simonian, A.; Chin, B.A. Sensors for agriculture and the food industry. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2010, 19, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, J.A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Suárez, L.; Fereres, E. Thermal and narrowband multispectral remote sensing for vegetation monitoring from an unmanned aerial vehicle. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, X. Deep Learning-Based Fusion of Optical, Radar, and LiDAR Data for Advancing Land Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhande, A.; Malik, R. Hyper spectral remote sensing for damage detection and classification models in agriculture—A review. Inf. Technol. Ind. 2021, 9, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Berni, J.A.; Suárez, L.; Fereres, E. A new era in remote sensing of crops with unmanned robots. SPIE Newsroom 2008, 10, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Propst, K.; Hirsch, C.D. Current methods and future needs for visible and non-visible detection of plant stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1585413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.K.; Ramirez, R.A.; Kwon, T.H. Acquisition of high-resolution topographic information in forest environments using integrated UAV-LiDAR system: System development and field demonstration. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Dao, P.D.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Shang, J. Recent advances of hyperspectral imaging technology and applications in agriculture. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégué, A.; Arvor, D.; Bellon, B.; Betbeder, J.; De Abelleyra, D.; PD Ferraz, R.; Lebourgeois, V.; Lelong, C.; Simões, M.; Verón, S.R. Remote sensing and cropping practices: A review. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.S.; Abidin, M.S.; Emmanuel, A.A.; Hasan, H.S. Robotics and automation in agriculture: Present and future applications. Appl. Model. Simul. 2020, 4, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bagyaveereswaran, V.; Ghorui, A.; Anitha, R. Automation of agricultural tasks with robotics-agrobot. In Proceedings of the 2019 Innovations in Power and Advanced Computing Technologies (i-PACT), Vellore, India, 22–23 March 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, T.; Ali, A.; Anwar, S.; Farooq, S.; Altabey, W.A.; Kouritem, S.A.; Noori, M. Implementation of Fruit Plucking Robot in Apple Harvesting: A Review. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Arellano, M.; Griepentrog, H.W.; Reiser, D.; Paraforos, D.S. 3-D imaging systems for agricultural applications—A review. Sensors 2016, 16, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Kaushik, K.; Tewatia, A.; Quraishi, S.J. Robotics and Automation in Modern Agriculture: Revolutionizing Harvesting and Processing. In Precision and Intelligence in Agriculture: Advanced Technologies for Sustainable Farming; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2026; pp. 153–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Enhancing smart farming through the applications of Agriculture 4.0 technologies. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2022, 3, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C. Incorporating artificial intelligence technology in smart greenhouses: Current State of the Art. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatise, M.B.; Hancke, G.P. A review on challenges of autonomous mobile robot and sensor fusion methods. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 39830–39846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabre, K.R.; Lopes, H.R.; D’monte, S.S. Intelligent decision support system for smart agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Smart City and Emerging Technology (ICSCET), Mumbai, India, 5 January 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shweta, C.M.; Gawande, A.D.; Ingole, K.R. Review on Decision Support System Approach for Agriculture Field. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2017, 6, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, S.A.; Choudhary, A.; Sachan, V.K. Design issues for wireless sensor networks and smart humidity sensors for precision agriculture: A review. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Soft Computing Techniques and Implementations (ICSCTI), Faridabad, India, 8–10 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaru, L.; Irigireddy, B.C.; Davis, B. DeepQC: A deep learning system for automatic quality control of in-situ soil moisture sensor time series data. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guan, K.; Peng, B.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Y.; Pan, M.; Franz, T.E.; Heeren, D.M.; Rudnick, D.R.; et al. Challenges and opportunities in precision irrigation decision-support systems for center pivots. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 053003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, F.; D’Haese, M.; Fiems, D.; Azadi, H. The intentions of agricultural professionals towards diffusing wireless sensor networks: Application of technology acceptance model in Southwest Iran. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Qiao, Y. AI, sensors, and robotics for smart agriculture. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrile, V.; Simonetti, S.; Citroni, R.; Fotia, A.; Bilotta, G. Experimenting agriculture 4.0 with sensors: A data fusion approach between remote sensing, UAVs and self-driving tractors. Sensors 2022, 22, 7910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyana, A.; Kautish, S.; Karthik, P.S.; Al-Baltah, I.A.; Jasser, M.B.; Mohamed, A.W. Accelerating crop yield: Multisensor data fusion and machine learning for agriculture text classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 20795–20805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yan, H. Multi-sensor data fusion algorithm of wisdom agriculture based on fusion set. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Virtual Reality and Intelligent Systems (ICVRIS), Hunan, China, 10–11 August 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffreda, I.; Casaccia, S.; Revel, G.M. A multi-sensor fusion approach based on pir and ultrasonic sensors installed on a robot to localise people in indoor environments. Sensors 2023, 23, 6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Ma, L.; Chen, Z.; Xu, B. Benchmarking robustness of ai-enabled multi-sensor fusion systems: Challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–9 December 2023; pp. 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.; Kc, K.; Fulton, J.P.; Shearer, S.; Ozkan, E. Remote sensing in agriculture—Accomplishments, limitations, and opportunities. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Remote sensing and precision agriculture technologies for crop disease detection and management with a practical application example. Engineering 2020, 6, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Shivandu, S.K. Integrating artificial intelligence and Internet of Things (IoT) for enhanced crop monitoring and management in precision agriculture. Sens. Int. 2024, 5, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, J. (Ed.) Robotics and Automation for Improving Agriculture, 1st ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lągiewska, M.; Panek-Chwastyk, E. Integrating remote sensing and autonomous robotics in precision agriculture: Current applications and workflow challenges. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ušinskis, V.; Nowicki, M.; Dzedzickis, A.; Bučinskas, V. Sensor-fusion based navigation for autonomous mobile robot. Sensors 2025, 25, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloret, J.; Sendra, S.; Garcia, L.; Jimenez, J.M. A wireless sensor network deployment for soil moisture monitoring in precision agriculture. Sensors 2021, 21, 7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekha, P.; Rangan, V.P.; Ramesh, M.V.; Nibi, K.V. High yield groundnut agronomy: An IoT based precision farming framework. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), San Jose, CA, USA, 19–22 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Jain, A.; Gupta, P.; Chowdary, V. Machine learning applications for precision agriculture: A comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 4843–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokade, A.; Singh, M.; Arora, S.K.; Nizeyimana, E. IOT-Based Medical Informatics Farming System with Predictive Data Analytics Using Supervised Machine Learning Algorithms. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 8434966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, Y.; Namuduri, S.; Burton, L.; Sarwat, A.; Bhansali, S. Machine learning techniques in wireless sensor network based precision agriculture. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 167, 037522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Ma, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, G. Anomaly detection for internet of things time series data using generative adversarial networks with attention mechanism in smart agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 890563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.K.; Takei, K. Toward Environmentally Friendly Hydrogel-Based Flexible Intelligent Sensor Systems. Adv. Intell. Discov. 2025. Early View. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, D.R.; Deepa, N.; Elavarasan, D.; Srinivasan, K.; Chauhdary, S.H.; Iwendi, C. Sensors driven AI-based agriculture recommendation model for assessing land suitability. Sensors 2019, 19, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhao, Z. Imitation Learning of Complex Behaviors for Multiple Drones with Limited Vision. Drones 2023, 7, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Liyuan, H.; Wong, H.; Xing, J. Intelligent agricultural forecasting system based on wireless sensor. J. Netw. 2013, 8, 1817. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, D.; Martínez, J.F.; Sendra, J.; Rubio, G. Development of a decision making algorithm for traffic jams reduction applied to intelligent transportation systems. J. Sens. 2016, 2016, 9271986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Kaur, G.; Machavaram, R.; Bhattacharya, M. Intelligent cotton ball maturity prediction model for smart agriculture. In AIP Conference Proceedings 2024; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 2919, p. 050004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gut, I.; Curiac, D.I. Hierarchical data aggregation framework for autonomous decision making in intelligent cities based on wireless sensor networks. In Proceedings of the 11th WSEAS International Conference on Automatic Control, Modelling and Simulation, Budapest, Hungary, 3–5 September 2009; pp. 462–467. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/2169104.2169187 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Moreira, F. The journal of knowledge engineering special issue on WorldCist’19—Seventh World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies. Expert Syst. 2021, 38, e12711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.; He, J. Edge computing-enabled smart agriculture: Technical architectures, practical evolution, and bottleneck breakthroughs. Sensors 2025, 25, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudda, S.; Haribabu, K. A review on WSN based resource constrained smart IoT systems. Discov. Internet Things 2025, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.K.; Nagwanshi, K.K.; Shukla, M.K.; Aswal, S. Intelligent farming using energy efficient routing protocol with efficient transmission in agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Lalitpur, Nepal, 26–28 April 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1261–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deohate, A.; Rojatkar, D. Middleware challenges and platform for IoT-A survey. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 3–5 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyasin, M.S.; Sobhani, M.E.; Nasrin, S.; Al Rafi, A.S.; Islam, A.M. CropSynergy: Harnessing IoT Solutions for Smart and Efficient Crop Management. Crop Design 2025, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, P. Framework and case studies of intelligence monitoring platform in facility agriculture ecosystem. In Proceedings of the 2013 Second International Conference on Agro-Geoinformatics (Agro-Geoinformatics), Fairfax, VA, USA, 12–16 August 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, K.M.; El-Hady, W.M.; Samy, F.M. Technologies, Protocols, and applications of Internet of Things in greenhouse Farming: A survey of recent advances. Inf. Process. Agric. 2025, 12, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, S.; Liu, Y.; Meng, S.; Chi, X.; Ma, R.; Yan, C. Fast wireless sensor for anomaly detection based on data stream in an edge-computing-enabled smart greenhouse. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2022, 8, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, M.Y. Satellite and drone multi-spectral and thermal images data fusion for intelligent agriculture monitoring and decision making support. In Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology XXV; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12727, pp. 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Saranti, A.; Angerschmid, A.; Retzlaff, C.O.; Gronauer, A.; Pejakovic, V.; Medel-Jimenez, F.; Krexner, T.; Gollob, C.; Stampfer, K. Digital transformation in smart farm and forest operations needs human-centered AI: Challenges and future directions. Sensors 2022, 22, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, B.G.; Helfer, G.A.; Barbosa, J.L.; Silva, M.R.; de Figueiredo, R.M.; Modolo, R.C.; Yamin, A.C. A computational model for ubiquitous intelligent services in indoor agriculture. In Proceedings of the 25th Brazillian Symposium on Multimedia and the Web, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 29 October–1 November 2019; pp. 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Yao, M.H.; Kow, P.Y.; Kuo, B.J.; Chang, F.J. An Artificial Intelligence-Powered Environmental Control System for Resilient and Efficient Greenhouse Farming. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswara, S.M.; Padmanaban, J. Interpretable deep learning models for independent fertilizer and crop recommendation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 41721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.M.; Hong, Z.W.; Cheng, W.K. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in sensors and applications. Sensors 2024, 24, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.M.; Gomes, J.M.; Martins, I.A.; Ruano, A.E. A neural network based intelligent predictive sensor for cloudiness, solar radiation and air temperature. Sensors 2012, 12, 15750–15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhao, P.; Qian, Y.; Yang, G.; Hao, X.; Mei, X.; Yang, X.; He, J. A Comprehensive Review of Big Data Intelligent Decision-Making Models for Smart Farms. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoo, E.E.; Akansah, E.; Mendonça, I.; Aritsugi, M. Monitoring and control framework for IoT, implemented for smart agriculture. Sensors 2023, 23, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavasso-Rita, Y.L.; Papalexiou, S.M.; Li, Y.; Elshorbagy, A.; Li, Z.; Schuster-Wallace, C. Crop models and their use in assessing crop production and food security: A review. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, B.; Bang, J. The state-of-the-art of knowledge-intensive agriculture: A review on applied sensing systems and data analytics. J. Sens. 2018, 2018, 3528296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Briones, A.; Castellanos-Garzón, J.A.; Mezquita Martín, Y.; Prieto, J.; Corchado, J.M. A framework for knowledge discovery from wireless sensor networks in rural environments: A crop irrigation systems case study. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 6089280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.M.; Kechadi, M.T. Crop knowledge discovery based on agricultural big data integration. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Machine Learning and Soft Computing; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogue, R. Sensors key to advances in precision agriculture. Sens. Rev. 2017, 37, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manono, B.O.; Sadiq, F.K.; Sadiq, A.A.; Matsika, T.A.; Tanko, F. Impacts of air quality on global crop yields and food security: An integrative review and future outlook. Air 2025, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adão, T.; Hruška, J.; Pádua, L.; Bessa, J.; Peres, E.; Morais, R.; Sousa, J.J. Hyperspectral imaging: A review on UAV-based sensors, data processing and applications for agriculture and forestry. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagan, V.; Peterson, K.T.; Maimaitijiang, M.; Sidike, P.; Sloan, J.; Greeling, B.A.; Maalouf, S.; Adams, C. Monitoring inland water quality using remote sensing: Potential and limitations of spectral indices, bio-optical simulations, machine learning, and cloud computing. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 205, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, J.; Naraseeyappa, S.; Ankalaki, S. Analysis of agriculture data using data mining techniques: Application of big data. J. Big Data 2017, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.B.B.; Adriano Filho, J.; da Rocha, A.R.; Gondim, R.S.; de Souza, J.N. Outlier detection methods and sensor data fusion for precision agriculture. In Simpósio Brasileiro de Computação Ubíqua e Pervasiva (SBCUP); Sociedade Brasileira de Computação: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017; pp. 928–937. ISSN 2595-6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Xia, N.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Z. A Classification Prediction Method using Rough Set and Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computing and Artificial Intelligence, Tianjin, China, 18–21 March 2022; pp. 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manono, B.O.; Khan, S.; Kithaka, K.M. A Review of the Socio-Economic, Institutional, and Biophysical Factors Influencing Smallholder Farmers’ Adoption of Climate Smart Agricultural Practices in Sub-Saharan Africa. Earth 2025, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Sachdeva, A.; Sharma, K.; Alsharif, M.H.; Uthansakul, P.; Uthansakul, M. Hyperspectral imaging and its applications: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daum, T.; Ravichandran, T.; Kariuki, J.; Chagunda, M.; Birner, R. Connected cows and cyber chickens? Stocktaking and case studies of digital livestock tools in Kenya and India. Agric. Syst. 2022, 196, 103353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.K.; Sobti, R.; Jain, A.; Malik, P.K.; Le, D.N. LoRa based intelligent soil and weather condition monitoring with internet of things for precision agriculture in smart cities. IET Commun. 2022, 16, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munirathinam, S. Drift detection analytics for iot sensors. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 180, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, P.; Boruta, F.; Czermak, P.; Ebrahimi, M. Fouling Control of Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) in Aquatic and Aquacultural Environments: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.W.; Lin, Y.B.; Hung, H.N. CalibrationTalk: A farming sensor failure detection and calibration technique. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 6893–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnitskaya, A. Calibration update and drift correction for electronic noses and tongues. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda Britez, D.A.; Tapia, A.; Millán Gata, P. A self-calibration algorithm for soil moisture sensors using deep learning. Appl. Intell. 2025, 55, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Mi, Y.; Glassmaker, N.; Shakouri, A.; Alam, M.A. In situ drift monitoring and calibration of field-deployed potentiometric sensors using temperature supervision. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 2799–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddar, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A. A comprehensive overview of inertial sensor calibration techniques. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. 2017, 139, 011006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelman, D.; Kinzli, K.D.; Kunberger, T. Calibration of the 10HS soil moisture sensor for southwest Florida agricultural soils. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2013, 139, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahuja, R. Development of semi-automatic recalibration system and curve-fit models for smart soil moisture sensor. Measurement 2022, 203, 111907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oommen, B.A.; Philip, J. Soil moisture evaluation with spiral fringing field capacitive sensors. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 3735–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanso, T.; Gromaire, M.C.; Ramier, D.; Dubois, P.; Chebbo, G. An investigation of the accuracy of EC5 and 5TE capacitance sensors for soil moisture monitoring in urban soils-laboratory and field calibration. Sensors 2020, 20, 6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Teruel, J.D.; Torres-Sánchez, R.; Blaya-Ros, P.J.; Toledo-Moreo, A.B.; Jiménez-Buendía, M.; Soto-Valles, F. Design and calibration of a low-cost SDI-12 soil moisture sensor. Sensors 2019, 19, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marios, S.; Georgiou, J. Precision agriculture: Challenges in sensors and electronics for real-time soil and plant monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), Turin, Italy, 19–21 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.; Alsweiss, S.; Toker, O.; Razdan, R.; Santos, J. An overview of autonomous vehicles sensors and their vulnerability to weather conditions. Sensors 2021, 21, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Liu, W.; Huo, Z.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.; Xin, C.; Bai, Y.; Liang, Z.; Gong, Y.; Qian, Y.; et al. Current status and prospects of research on sensor fault diagnosis of agricultural internet of things. Sensors 2023, 23, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramson, S.J.; León-Salas, W.D.; Brecheisen, Z.; Foster, E.J.; Johnston, C.T.; Schulze, D.G.; Filley, T.; Rahimi, R.; Soto, M.J.; Bolivar, J.A.; et al. A self-powered, real-time, LoRaWAN IoT-based soil health monitoring system. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 9278–9293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuteja, G.; Rani, S.; Sharma, A.; Singla, S. Integrating Wireless Sensor Networks with IoT for Enhanced Data-Driven Industry Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT), Goa, India, 6–8 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresl, J.; Fazackerley, S.; Lawrence, R. Practical Precision Agriculture with LoRa based Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Sensor Networks, Online, 9–10 February 2021; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, B.H.; Kurnaz, S. Secure low-cost photovoltaic monitoring system based on LoRaWAN network and artificial intelligence. Discov. Comput. 2024, 27, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.; Parada, R.; Monzo, C. Global emergency system based on WPAN and LPWAN hybrid networks. Sensors 2022, 22, 7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, P.; Sugeru, H.; Wibowo, E.P. Wireless sensor networks for precision agriculture: A review of npk sensor implementations. Sensors 2023, 24, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noshad, Z.; Javaid, N.; Saba, T.; Wadud, Z.; Saleem, M.Q.; Alzahrani, M.E.; Sheta, O.E. Fault detection in wireless sensor networks through the random forest classifier. Sensors 2019, 19, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.D.; Tomaz, D.C.; Martins, R.N.; Rosas, J.T.; Santos, F.F.; Portes, M.F. Optical sensors for precision agriculture: An outlook. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2019, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P.; Ganguly, A.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Internet of Things and smart sensors in agriculture: Scopes and challenges. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, H.M.; Nordin, R.; Gharghan, S.K.; Jawad, A.M.; Ismail, M. Energy-efficient wireless sensor networks for precision agriculture: A review. Sensors 2017, 17, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, D.C.; Kundu, I.; Sharma, A.; Shivhare, P.; Afzal, A.; Soudagar, M.E.; Park, S.G. Internet of Things integrated with solar energy applications: A state-of-the-art review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 24597–24652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, S.; Wadumi Namkusong, J.; Lee, J.A.; Liz Crespo, M. Design and performance evaluation of a low-cost autonomous sensor interface for a smart iot-based irrigation monitoring and control system. Sensors 2019, 19, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.G.; He, P. A comprehensive survey on the reliability of mobile wireless sensor networks: Taxonomy, challenges, and future directions. Inf. Fusion 2018, 44, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Varshney, N.; Gentile, C.; Blandino, S.; Chuang, J.; Golmie, N. Integrated sensing and communication: Enabling techniques, applications, tools and data sets, standardization, and future directions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 23416–23440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikhpour, S.; Mahani, A.; Rashvand, H.F. Agricultural applications of underground wireless sensor systems: A technical review. In Wireless Sensor Systems for Extreme Environments: Space, Underwater, Underground and Industrial; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 351–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustemi, A.; Dalipi, F. Synergizing IoT, AI, and blockchain for smart agriculture: Challenges, opportunities, and future directions. Internet Things 2025, 34, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zhang, X. Mapping crop phenology in near real-time using satellite remote sensing: Challenges and opportunities. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Han, Z.; Gao, L.; Zhang, T.; Wu, R.; Zhang, H. Advances in Hyperspectral Image Unmixing: From Algorithmic Frameworks to Practical Applications. Inf. Geogr. 2025, 2, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.F.; Castro-Camus, E.; Ottaway, D.J.; López-Higuera, J.M.; Feng, X.; Jin, W.; Jeong, Y.; Picqué, N.; Tong, L.; Reinhard, B.M.; et al. Roadmap on optical sensors. J. Opt. 2017, 19, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussi, A.; Zero, E.; Sacile, R.; Trinchero, D.; Fossa, M. Smart sensors and smart data for precision agriculture: A review. Sensors 2024, 24, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, M.; Bovo, M.; Santolini, E.; Tassinari, P.; Torreggiani, D.; Barbaresi, A. Enhancing Sensor Precision Through Calibration: A Case Study in Agricultural Monitoring Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor), Padua, Italy, 29–31 October 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmira, R.; Lubis, D.P.; Sumardjo, S.; Fatchiya, A.; Supriyanto, S. Adapting to smart farming: Communication media and local knowledge in overcoming technical challenges. In BIO Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2025; Volume 171, p. 04007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagireddy, S.K. Sensor-Driven Autonomy in Agriculture: A Multi-Modal Approach to Precision Farming. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2025, 7, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.Y.; Lee, K.B. Hardware-In-The-Loop (HIL) Simulation-based Interoperability Testing Method of Smart Sensors in Smart Grids. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems (ICPS), St. Louis, MO, USA, 12–15 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, A.; Ferri, G.; Ursini, D.; Zompanti, A.; Sabatini, A.; Stornelli, V. Towards Smart Sensor Systems for Precision Farming: Electrode Potential Energy Harvesting from Plants’ Soil. In Proceedings of the 2022 29th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), Glasgow, UK, 24–26 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhong, W.; Huang, S.; He, X.; Cai, W.; Ma, R.; Jiang, T.; You, S.; Wang, L.; Li, W. Research Progress on the Corrosion Mechanism and Protection Monitoring of Metal in Power Equipment. Coatings 2025, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Sharma, S. A comprehensive review on the Internet of Things in precision agriculture. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 18123–18198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Shivakoti, G.P.; Zulfiqar, F.; Kamran, M.A. Farm risks and uncertainties: Sources, impacts and management. Outlook Agric. 2016, 45, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giua, C.; Materia, V.C.; Camanzi, L. Smart farming technologies adoption: Which factors play a role in the digital transition? Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekala, M.S.; Viswanathan, P. A Survey: Smart agriculture IoT with cloud computing. In Proceedings of the 2017 international conference on microelectronic devices, circuits and systems (ICMDCS), Vellore, India, 10–12 August 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.A.; Bukhari, W.A.; Adnan, M.; Kashif, M.I.; Danish, A.; Sikander, A. Security and privacy in IoT-based Smart Farming: A review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 15971–16031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Khorsandroo, S.; Mittal, S. Security and privacy in smart farming: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 34564–34584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. How Trade-off between increasing crop yield and privacy protection. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2017), 29–30 July 2017; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daousis, S.; Peladarinos, N.; Cheimaras, V.; Papageorgas, P.; Piromalis, D.D.; Munteanu, R.A. Overview of protocols and standards for wireless sensor networks in critical infrastructures. Future Internet 2024, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhussain, S.H.; Mahmmod, B.M.; Alwhelat, A.; Shehada, D.; Shihab, Z.I.; Mohammed, H.J.; Abdulameer, T.H.; Alsabah, M.; Fadel, M.H.; Ali, S.K.; et al. A comprehensive review of sensor technologies in IOT: Technical aspects, challenges, and future directions. Computers 2025, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, E.G.; Sotiriadis, S.; Soultanopoulos, T.; Renta, P.T.; Buyya, R.; Bessis, N. Internet of things as a service (itaas): Challenges and solutions for management of sensor data on the cloud and the fog. Internet Things 2018, 3, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noura, M.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Gaedke, M. Interoperability in internet of things: Taxonomies and open challenges. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2019, 24, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, D.J.; Panduru, K.; Walsh, J. Exploring the unseen: A survey of multi-sensor fusion and the role of explainable ai (xai) in autonomous vehicles. Sensors 2025, 25, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tey, Y.S.; Brindal, M.; Wong, S.Y.; Ardiansyah; Ibragimov, A.; Yusop, M.R. Evolution of precision agricultural technologies: A patent network analysis. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blind, K.; Pohlisch, J.; Zi, A. Publishing, patenting, and standardization: Motives and barriers of scientists. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamabolo, E.; Mashala, M.J.; Mugari, E.; Mogale, T.E.; Mathebula, N.; Mabitsela, K.; Ayisi, K.K. Application of precision agriculture technologies for crop protection and soil health. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, F.J.; Elliott, T.V. Regional and on-farm wireless sensor networks for agricultural systems in Eastern Washington. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 61, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. The role of modern agricultural technologies in improving agricultural productivity and land use efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1675657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.K.; Karim, S.; Zeadally, S.; Nebhen, J. Recent trends in internet-of-things-enabled sensor technologies for smart agriculture. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 23583–23598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palta, P.; Kumar, A.; Palta, A. Leveraging Dielectric Properties, Remote Sensing, and Sensor Technology in Agriculture: A Perspective on Industry and Emerging Technologies. In Industry 5.0 and Emerging Technologies: Transformation Through Technology and Innovations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, I.; Negi, S.; Chauhan, A. Explainable AI for Next Generation Agriculture—Current Scenario and Future Prospects. In Computational Intelligence in Internet of Agricultural Things; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, B.; Kononets, Y.; Csambalik, L. Adoption of drone, sensor, and robotic technologies in organic farming systems of Visegrad countries. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelpfennig, D.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. Farm Types and Precision Agriculture Adoption: Crops, Regions, SOIL variability, and Farm Size. Global Institute for Agri-Tech Economics Working Paper. 2020, pp. 1–20. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/304070/files/Schimmelpfennig_LDB_GIATE_Working_Paper_01_20.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.R.; Yadav, M.C.; Yadav, V.K.; Channi, A.S.; Chouria, A.; Kumar, N.; Dall, H.; Nazir, T. The Role of Variable Rate Technology (VRT) in Modern Agriculture: A Review. J. Adv. Biol. Biotechnol. 2025, 28, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colussi, J.; Sonka, S.; Schnitkey, G.D.; Morgan, E.L.; Padula, A.D. A comparative study of the influence of communication on the adoption of digital agriculture in the United States and Brazil. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.; Gandorfer, M. Adoption of digital technologies in agriculture—An inventory in a european small-scale farming region. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogstra, A.G.; Silvius, J.; De Olde, E.M.; Candel, J.J.; Termeer, C.J.; Van Ittersum, M.K.; De Boer, I.J. The transformative potential of circular agriculture initiatives in the North of the Netherlands. Agric. Syst. 2024, 214, 103833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, N.; Gandhic, N.; Saxena, L. Wireless sensor networks: Apple farming in Northern India. In Proceedings of the 2012 Fourth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks, Mathura, India, 3–5 November 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Pilot-scale studies, scaling-up, and technology transfer. In Iron Ores Bioprocessing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyenuga, M.O.; Omale, S.A. Is Africa Jinxed? Exploring the challenges of technology access and adoption in Africa. Afr. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 7, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Liu, L.; Zhao, J.; Kang, X.; Wang, W. Digital technologies adoption and economic benefits in agriculture: A mixed-methods approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.J.; Jankowska, A. The potential and productivity of agriculture in Nigeria. Prepr. Ser. Agric. Policy 2025, 38, 2025070223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, A.M.; Okuneye, P.A.; Olarewaju, T.O. Patterns and determinants of adoption of crop production technologies among food crop farmers in Nigeria. Niger. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 5, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragomeli, R.; Annunziata, A.; Punzo, G. Promoting the transition towards agriculture 4.0: A systematic literature review on drivers and barriers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, R.; Wynn, J.T.; Lindner, J.R.; Palmer, K. Evaluating Brazilian agriculturalists’ IoT smart agriculture adoption barriers: Understanding stakeholder salience prior to launching an innovation. Sensors 2022, 22, 6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomide, R.L.; Inamasu, R.Y.; Queiroz, D.M.; Mantovani, E.C.; Santos, W.F. An automatic data acquisition and control mobile laboratory network for crop production systems data management and spatial variability studies in the Brazilian center-west region. In 2001 ASAE Annual Meeting; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 1998; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laveglia, S.; Altieri, G.; Genovese, F.; Matera, A.; Di Renzo, G.C. Advances in sustainable crop management: Integrating precision agriculture and proximal sensing. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 3084–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbedo, J.G. A review of artificial intelligence techniques for wheat crop monitoring and management. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elijah, O.; Rahman, T.A.; Orikumhi, I.; Leow, C.Y.; Hindia, M.N. An overview of Internet of Things (IoT) and data analytics in agriculture: Benefits and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 3758–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornese, I.; Matera, A.; Rashvand, M.; Genovese, F. Use of probes and sensors in agriculture—Current trends and future prospects on intelligent monitoring of soil moisture and nutrients. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 4154–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajib, M.M.; Sayem, A.S. Innovations in Sensor-Based Systems and Sustainable Energy Solutions for Smart Agriculture: A Review. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.; Khan, M.A.; Noor, F.; Ullah, I.; Alsharif, M.H. Towards the unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): A comprehensive review. Drones 2022, 6, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, M.; Ijaz, M.F. Recent advances in big data, machine, and deep learning for precision agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1367538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Tripathi, A.K.; Mittalz, H. Technological revolutions in smart farming: Current trends, challenges & future directions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 201, 107217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayioğlu, M.A.; TÜRKER, U. Digital transformation for sustainable future-agriculture 4.0: A review. J. Agric. Sci. Tarim Bilim. Derg. 2021, 27, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J.; Popp, J. The outlook for precision farming in Hungary. Netw. Intell. Stud. 2018, 6, 91. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:cmj:networ:y:2018:i:12:p:91-99 (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Sarma, N.; Das, H.; Saikia, P. Borophene: The Frontier of Next-Generation Sensor Applications. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 622–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]