Impact of Ethylene Oxide Sterilization on PEDOT:PSS Electrophysiology Electrodes

Abstract

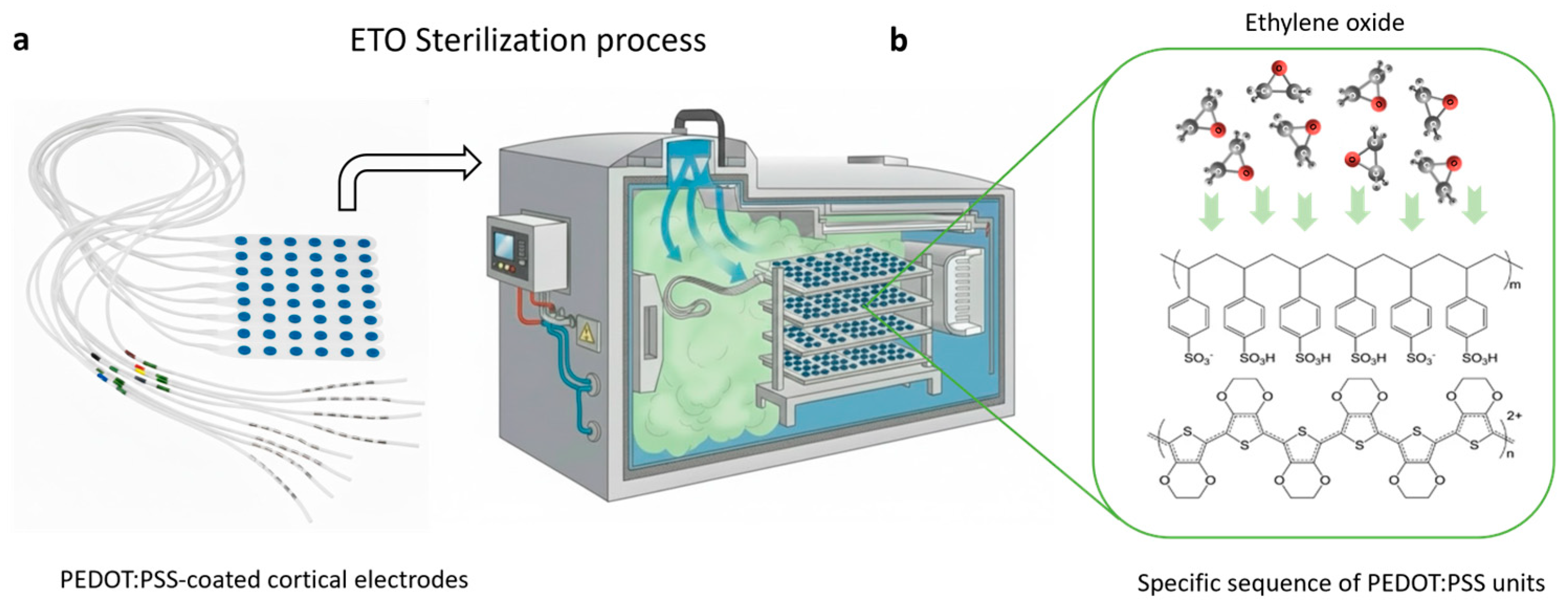

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Electrochemical Deposition of PEDOT:PSS

2.3. Ethylene Oxide Sterilization of PEDOT:PSS Electrodes

2.4. Electrochemical Characterizations

2.4.1. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

2.4.2. Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

2.4.3. Voltage Transient Response

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.6. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

3. Results

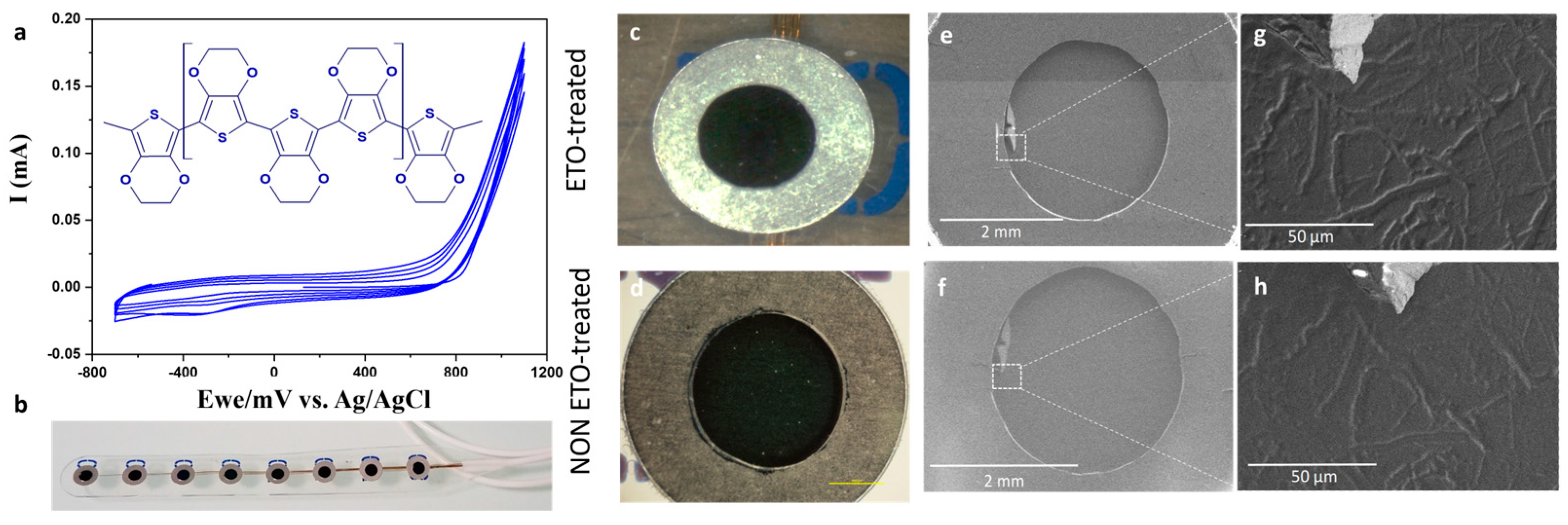

3.1. PEDOT:PSS Electrochemical Deposition

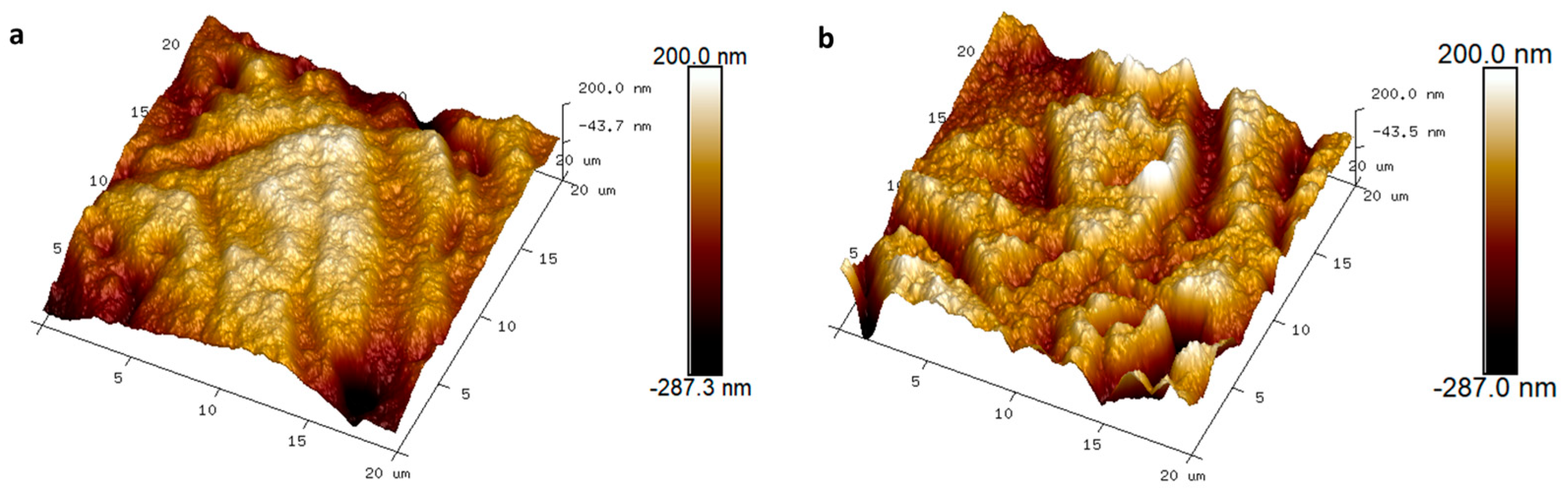

3.2. Morphology

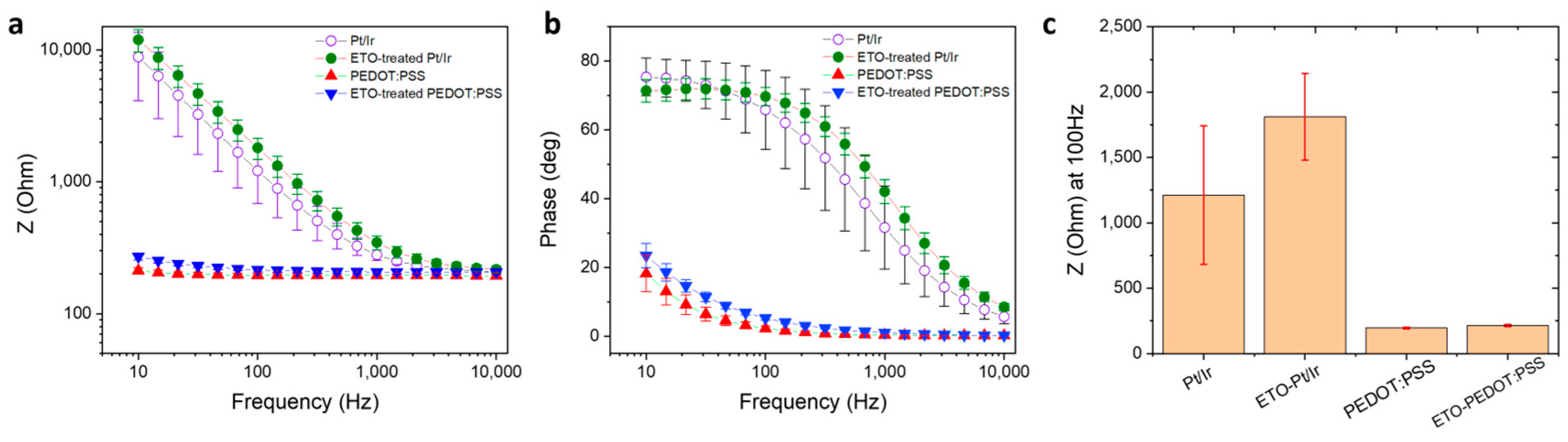

3.3. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

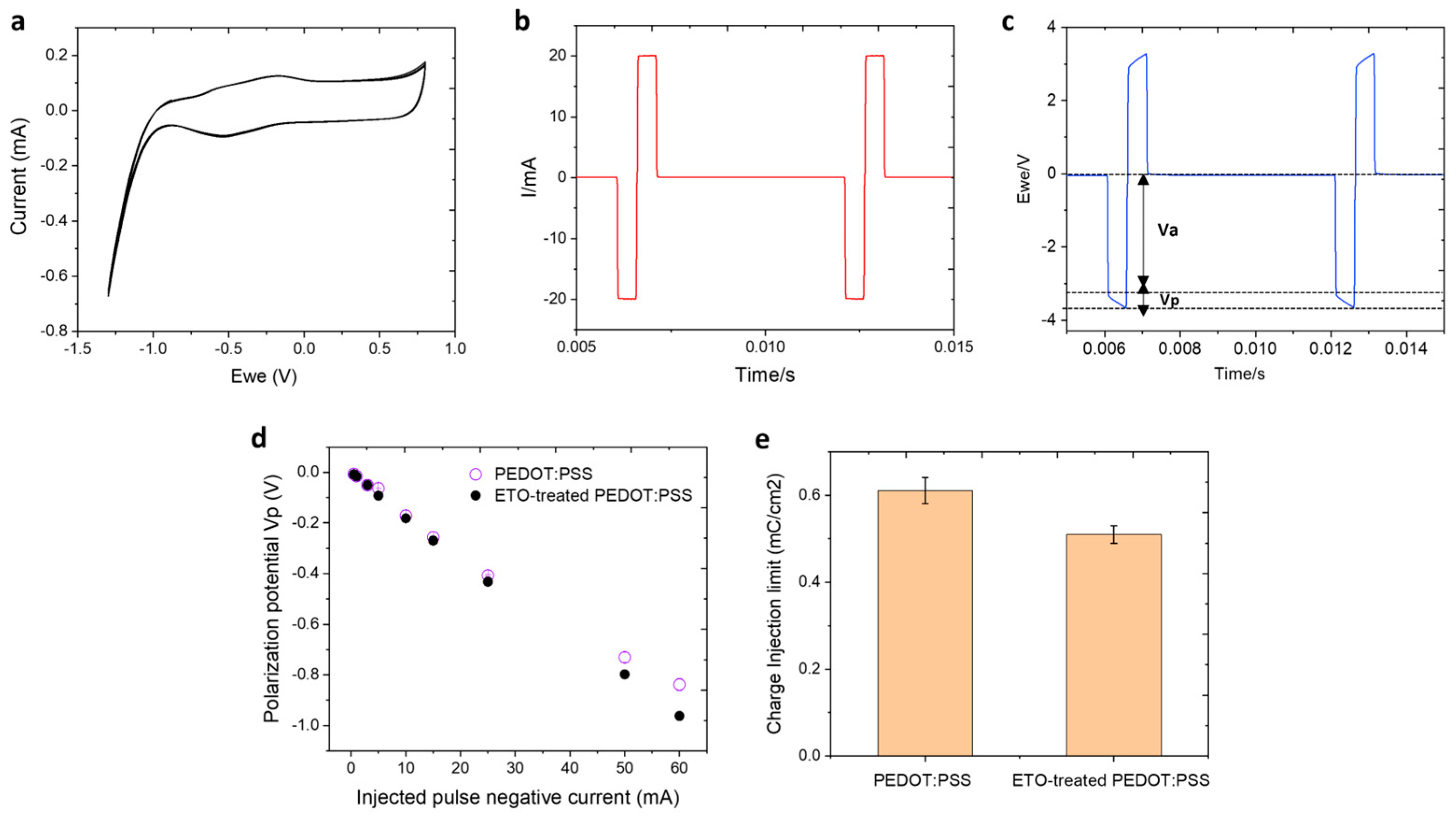

3.4. Charge Storage Capacity (CSC)

3.5. Electrical Stimulation

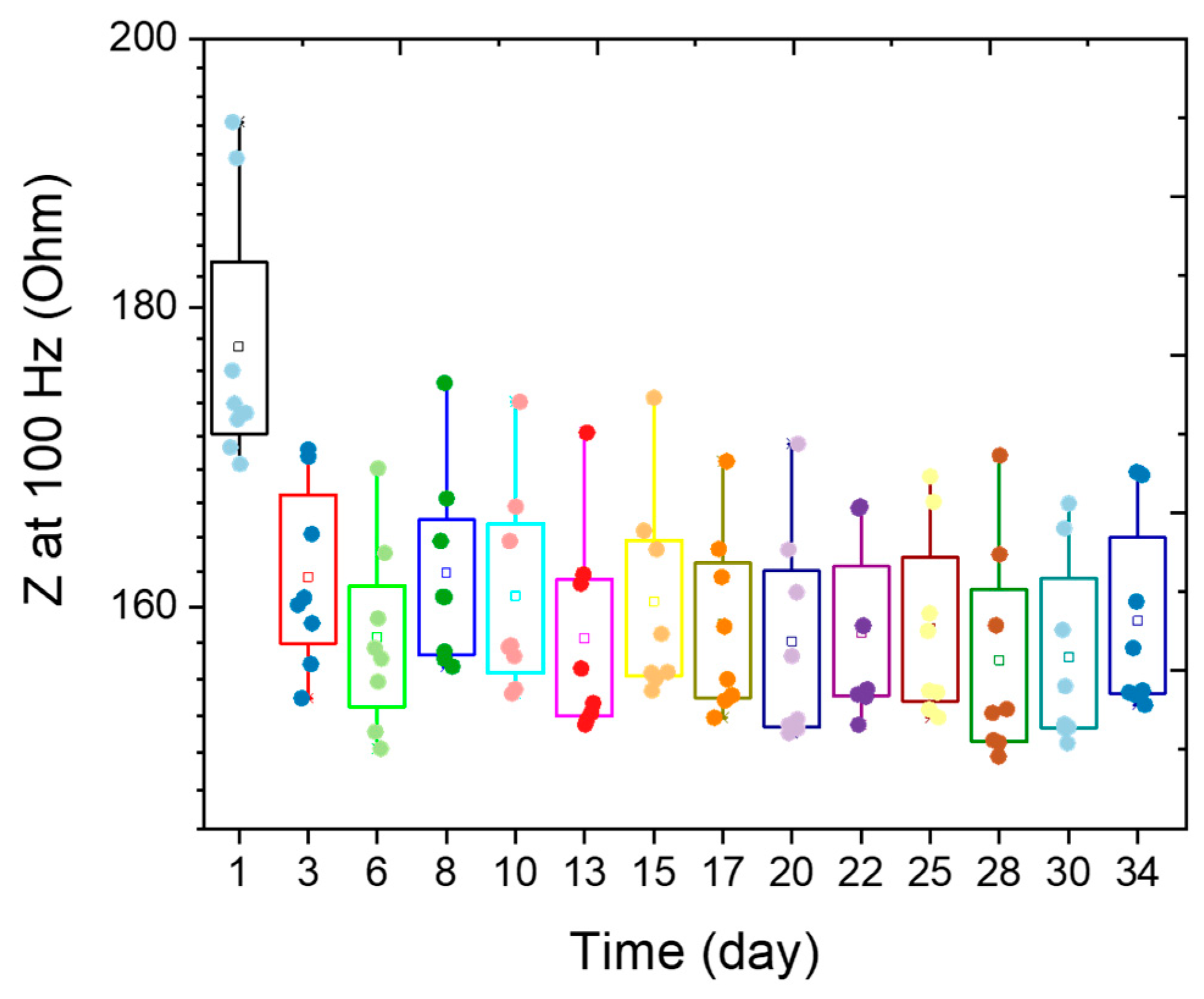

3.6. Long-Term Stability of EtO-Treated PEDOT:PSS Electrodes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cogan, S.F. Neural stimulation and recording electrodes. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2008, 10, 275–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, J.K.; Moxon, K.A.; Markowitz, R.S.; Nicolelis, M.A. Real-time control of a robot arm using simultaneously recorded neurons in the motor cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 1999, 2, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessberg, J.; Stambaugh, C.R.; Kralik, J.D.; Beck, P.D.; Laubach, M.; Chapin, J.K.; Kim, J.; Biggs, S.J.; Srinivasan, M.A.; Nicolelis, M.A. Real-time prediction of hand trajectory by ensembles of cortical neurons in primates. Nature 2000, 408, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatsopoulos, N.G.; Donoghue, J.P. The science of neural interface systems. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 32, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabid, A.L.; Chabardes, S.; Mitrofanis, J.; Pollak, P. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafkhani, N.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Adams, S.D.; Long, J.M.; Lissorgues, G.; Rousseau, L.; Orwa, J.O. Neural tissue-microelectrode interaction: Brain micromotion, electrical impedance, and flexible microelectrode insertion. J. Neurosci. Methods 2022, 365, 109388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polikov, V.S.; Tresco, P.A.; Reichert, W.M. Response of brain tissue to chronically implanted neural electrodes. J. Neurosci. Methods 2005, 148, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salatino, J.W.; Ludwig, K.A.; Kozai, T.D.; Purcell, E.K. Glial responses to implanted electrodes in the brain. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 862–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.A.; Lovell, N.H.; Wallace, G.G.; Poole-Warren, L.A. Conducting polymers for neural interfaces: Challenges in developing an effective long-term implant. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3393–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asplund, M.; Nyberg, T.; Inganäs, O. Electroactive polymers for neural interfaces. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 1374–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefer, E.W.; Botterman, B.R.; Romero, M.I.; Rossi, A.F.; Gross, G.W. Carbon nanotube coating improves neuronal recordings. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovat, V.; Pantarotto, D.; Lagostena, L.; Cacciari, B.; Grandolfo, M.; Righi, M.; Spalluto, G.; Prato, M.; Ballerini, L. Carbon nanotube substrates boost neuronal electrical signaling. Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 1107–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Kuzum, D. Graphene-based neurotechnologies for advanced neural interfaces. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 6, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, N.A.; Winter, J.O.; Clements, I.P.; Jan, E.; Timko, B.P.; Campidelli, S.; Pathak, S.; Mazzatenta, A.; Lieber, C.M.; Prato, M. Nanomaterials for neural interfaces. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 3970–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Martin, D.C. Electrochemical deposition and characterization of poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene) on neural microelectrode arrays. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2003, 89, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kim, D.H.; Hendricks, J.L.; Leach, M.; Northey, R.; Martin, D.C. Ordered surfactant-templated poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)(PEDOT) conducting polymer on microfabricated neural probes. Acta Biomater. 2005, 1, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.A.; Uram, J.D.; Yang, J.; Martin, D.C.; Kipke, D.R. Chronic neural recordings using silicon microelectrode arrays electrochemically deposited with a poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)(PEDOT) film. J. Neural Eng. 2006, 3, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.A.; Langhals, N.B.; Joseph, M.D.; Richardson-Burns, S.M.; Hendricks, J.L.; Kipke, D.R. Poly (3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)(PEDOT) polymer coatings facilitate smaller neural recording electrodes. J. Neural Eng. 2011, 8, 014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidian, M.R.; Martin, D.C. Multifunctional nanobiomaterials for neural interfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole-Warren, L.; Lovell, N.; Baek, S.; Green, R. Development of bioactive conducting polymers for neural interfaces. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2010, 7, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.; Jang, J. Conducting-polymer nanomaterials for high-performance sensor applications: Issues and challenges. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, N.; Lee, J.Y.; Nickels, J.D.; Schmidt, C.E. Micropatterned polypyrrole: A combination of electrical and topographical characteristics for the stimulation of cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, A.; Falk, D.; Bengtsson, K.; Maziz, A.; Filippini, D.; Robinson, N.D.; Jager, E.W. Patterning highly conducting conjugated polymer electrodes for soft and flexible microelectrochemical devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 14978–14985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajrala, V.S.; Elkhoury, K.; Pautot, S.; Bergaud, C.; Maziz, A. Hollow ring-like flexible electrode architecture enabling subcellular multi-directional neural interfacing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 227, 115182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.A.; Lovell, N.H.; Poole-Warren, L.A. Cell attachment functionality of bioactive conducting polymers for neural interfaces. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3637–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.A.; Hassarati, R.T.; Bouchinet, L.; Lee, C.S.; Cheong, G.L.; Yu, J.F.; Dodds, C.W.; Suaning, G.J.; Poole-Warren, L.A.; Lovell, N.H. Substrate dependent stability of conducting polymer coatings on medical electrodes. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5875–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Z.A.; Shaw, C.M.; Spanninga, S.A.; Martin, D.C. Structural, chemical and electrochemical characterization of poly (3, 4-Ethylenedioxythiophene)(PEDOT) prepared with various counter-ions and heat treatments. Polymer 2011, 52, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidian, M.R.; Daneshvar, E.D.; Egeland, B.M.; Kipke, D.R.; Cederna, P.S.; Urbanchek, M.G. Hybrid conducting polymer–hydrogel conduits for axonal growth and neural tissue engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2012, 1, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivnay, J.; Inal, S.; Collins, B.A.; Sessolo, M.; Stavrinidou, E.; Strakosas, X.; Tassone, C.; Delongchamp, D.M.; Malliaras, G.G. Structural control of mixed ionic and electronic transport in conducting polymers. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziz, A.; Özgür, E.; Bergaud, C.; Uzun, L. Progress in conducting polymers for biointerfacing and biorecognition applications. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2021, 3, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodagholy, D.; Doublet, T.; Gurfinkel, M.; Quilichini, P.; Ismailova, E.; Leleux, P.; Herve, T.; Sanaur, S.; Bernard, C.; Malliaras, G.G. Highly conformable conducting polymer electrodes for in vivo recordings. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, H268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, M.; Kaestner, E.; Hermiz, J.; Rogers, N.; Tanaka, A.; Cleary, D.; Lee, S.H.; Snider, J.; Halgren, M.; Cosgrove, G.R. Development and translation of PEDOT: PSS microelectrodes for intraoperative monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1700232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranti, A.S.; Schander, A.; Bödecker, A.; Lang, W. PEDOT: PSS coating on gold microelectrodes with excellent stability and high charge injection capacity for chronic neural interfaces. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 275, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, S.; Hendricks, J.; King, Z.A.; Sereno, A.J.; Richardson-Burns, S.; Martin, D.; Carmena, J.M. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of PEDOT microelectrodes for neural stimulation and recording. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2011, 19, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozai, T.D.; Catt, K.; Du, Z.; Na, K.; Srivannavit, O.; Haque, R.-U.M.; Seymour, J.; Wise, K.D.; Yoon, E.; Cui, X.T. Chronic in vivo evaluation of PEDOT/CNT for stable neural recordings. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 63, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodagholy, D.; Gelinas, J.N.; Thesen, T.; Doyle, W.; Devinsky, O.; Malliaras, G.G.; Buzsáki, G. NeuroGrid: Recording action potentials from the surface of the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehler, C.; Carli, S.; Fadiga, L.; Stieglitz, T.; Asplund, M. Tutorial: Guidelines for standardized performance tests for electrodes intended for neural interfaces and bioelectronics. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 3557–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajrala, V.S.; Saunier, V.; Nowak, L.G.; Flahaut, E.; Bergaud, C.; Maziz, A. Nanofibrous PEDOT-Carbon Composite on Flexible Probes for Soft Neural Interfacing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 780197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnola, V.; Bayon, C.; Descamps, E.; Bergaud, C. Morphology and conductivity of PEDOT layers produced by different electrochemical routes. Synth. Met. 2014, 189, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maziz, A.; Cointe, C.; Reig, B.; Bergaud, C. Impact of Ethylene Oxide Sterilization on PEDOT:PSS Electrophysiology Electrodes. Sensors 2026, 26, 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030877

Maziz A, Cointe C, Reig B, Bergaud C. Impact of Ethylene Oxide Sterilization on PEDOT:PSS Electrophysiology Electrodes. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):877. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030877

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaziz, Ali, Clement Cointe, Benjamin Reig, and Christian Bergaud. 2026. "Impact of Ethylene Oxide Sterilization on PEDOT:PSS Electrophysiology Electrodes" Sensors 26, no. 3: 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030877

APA StyleMaziz, A., Cointe, C., Reig, B., & Bergaud, C. (2026). Impact of Ethylene Oxide Sterilization on PEDOT:PSS Electrophysiology Electrodes. Sensors, 26(3), 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030877